Abstract

Introduction

In the U.S., afterschool programs are asked to promote moderate to vigorous physical activity. One policy that has considerable public health importance is California’s afterschool physical activity guidelines that indicate all children attending an afterschool program accumulate 30 minutes each day the program is operating. Few effective strategies exist for afterschool programs to meet this policy goal. The purpose of this study was to evaluate a multistep adaptive intervention designed to assist afterschool programs in meeting the 30-minute/day moderate to vigorous physical activity policy goal.

Design

A 1-year group randomized controlled trial with baseline (spring 2013) and post-assessment (spring 2014). Data were analyzed 2014.

Setting/participants

Twenty afterschool programs, serving >1,700 children (aged 6–12 years), randomized to either an intervention (n=10) or control (n=10) group.

Intervention

The employed framework, Strategies To Enhance Practice, focused on intentional programming of physical activity opportunities in each afterschool program’s daily schedule, and included professional development training to establish core physical activity competencies of staff and afterschool program leaders with ongoing technical assistance.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was accelerometry-derived proportion of children meeting the 30-minute/day moderate to vigorous physical activity policy.

Results

Children attending intervention afterschool programs had an OR of 2.37 (95% CI=1.58, 3.54) to achieve the physical activity policy at post-assessment compared to control afterschool programs. Sex-specific models indicated that the percentage of intervention girls and boys achieving the physical activity policy increased from 16.7% to 21.4% (OR=2.85, 95% CI=1.43, 5.68) and 34.2% to 41.6% (OR=2.26, 95% CI=1.35, 3.80), respectively. At post-assessment, six intervention afterschool programs increased the proportion of boys achieving the physical activity policy to ≥45% compared to one control afterschool program, while three intervention afterschool programs increased the proportion of girls achieving physical activity policy to ≥30% compared to no control afterschool programs.

Conclusions

The Strategies To Enhance Practice intervention can make meaningful changes in the proportion of children meeting the moderate to vigorous physical activity policy within one school year. Additional efforts are required to enhance the impact of the intervention.

Introduction

Afterschool programs (ASPs)1,2 are attempting to implement national- and state-level polices that define the amount of physical activity (PA) children should accumulate while the program is operating.3 One of the most promising sets of policies is from the PA guidelines created by the California After School Resource Center and California Department of Education.4 In 2009, the California Department of Education, in conjunction with the California After School Resource Center, developed the California After School Physical Activity Guidelines, which indicate that ASPs ensure that all children engage in a minimum of 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA) each day when the program is in session and that the program should schedule 60 minutes of PA opportunities daily. The importance of this guideline (referred hereafter as the PA policy) is reflected in the clearly defined programmatic (e.g., 60 minutes of scheduled PA opportunities each day) and behavioral (e.g., children accumulate 30 minutes of MVPA per day) goals, the latter which would provide at least half of the recommended daily minutes of MVPA.5

Unfortunately, the amount of MVPA children accumulate while attending an ASP falls well below existing standards.3,6,7 To address this, numerous intervention studies targeting PA in the ASP setting have been conducted in the past 10 years, with limited success.8-15 One of the primary barriers reported in studies is professional development training for PA. Staff often lack the necessary skills to create “activity-friendly” environments and are overwhelmed when adopting new curricula that call on them to play unfamiliar games.14-16 Moreover, a common observation across ASP studies is a high amount of employee turnover, both at the program leader and frontline staff level.15-17 Thus, interventions need to address staff skills, must be easily incorporated into exiting routines, and should avoid undue complexity.

The majority of ASPs provide some form of professional development training for their staff prior to the beginning of each school year.18,19 Also, many ASPs allocate ample time in their daily schedule for PA opportunities, yet often do not maximize the amount of time children are moving during these opportunities.1,7,17-21 A recent study17 found that focusing on training staff how to modify the games they already play with the children and working with ASP leaders to create daily schedules that inform staff of the types of games to play, the location the games should take place, the equipment required, and the staff responsible for facilitating, can increase MVPA. The objective of the current study was to evaluate the effectiveness of these PA strategies,17 embedded within a multistep adaptive intervention, to meet the 30 minutes of MVPA/day standard using a group RCT design.

Methods

Study Population and Design

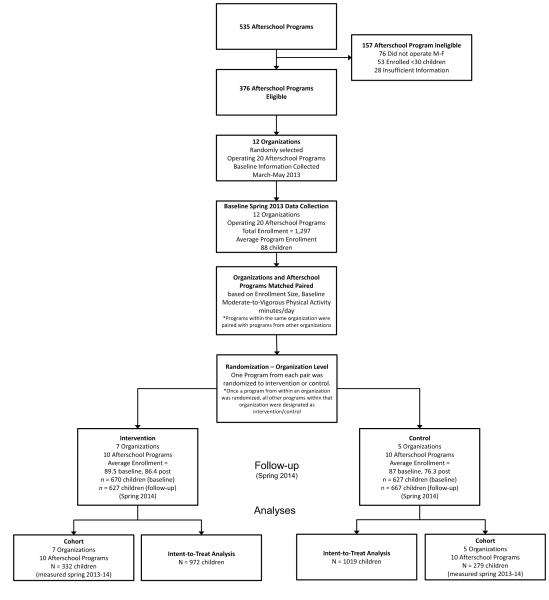

A total of 20 ASPs operating in a southeastern state, representing 12 ASP organizations, were randomly selected from a pre-existing list of 533 program providers within a 1.5-hour drive of the lead author’s university. The list was provided by a state-level organization responsible for policy and resources for ASPs. For this study, ASPs were defined as child care programs operating immediately after the school day, every day of the school year for a minimum of 2 hours, serving a minimum of 30 elementary-aged (6–12 years) children; operating in a school, community, or faith setting; and providing a snack, homework assistance/completion time, enrichment (e.g., arts and crafts), and opportunities for PA.22 Programs that were singularly focused (e.g., dance, tutoring) or PA focused (e.g., sports, activity clubs) were not eligible for participation. Of the 535 programs, 376 met the eligibility criteria—76 did not operate Monday through Friday, 53 enrolled <30 children, and 28 did not have sufficient information to evaluate eligibility. All enrolled children, staff, and ASP leaders in the ASPs were eligible to participate in the study. The only criterion excluding children from taking part in the PA assessment (i.e., accelerometry) was the inability to be physically active without an assistive device (e.g., wheelchair user, crutches). No other exclusion criteria were imposed on any of the study procedures. All study procedures were approved by the lead author’s IRB.

The design was a repeated cross-sectional group RCT with a delayed treatment group. This design is appropriate when outcomes are tracked at the group level (i.e., ASPs), instead of at the individual level (i.e., children)23,24 and is consistent with recent large-scale trials of site-level interventions for children and adolescents.8,25,26 The 20 ASPs were randomized into one of two conditions: (1) intervention group; or (2) control group. Sample size at the ASP and child levels were based on variance estimates from published studies7,17,19,27 and the ability to detect an effect size ≥0.35 or a 14% difference in the primary outcome.

Randomization

Randomization to intervention or control groups was performed after baseline data collection, during June 2013. Programs were match paired based on enrollment size and average levels of MVPA minutes/day, with one ASP within a matched pair randomized to either the intervention or control group. To minimize contamination, ASPs within the same organization were matched with ASPs from other organizations and were all randomized to the same condition. For instance, once an ASP from within an organization was randomized to the intervention group, all other ASPs from this organization were also designated to this group and their match pair designated to the other group. Enrollment size was selected as a matching variable to ensure comparable group composition on a marker of organizational complexity (e.g., an ASP with 30 children is less complex than an ASP serving >150 children/day). Activity levels were identified as pertinent matching variables because they served as the primary outcomes of interest. Randomization and enrollment were performed by study staff using a random number generator.

Intervention

To achieve the 30-minute/day MVPA policy goal, as defined by the California After School Physical Activity Guidelines,4 the following intervention approach was developed. A detailed description of the design and delivery of the intervention is described elsewhere.28 Briefly, the Strategies To Enhance Practice for Physical Activity (STEPs) conceptual framework involved a multistep adaptive29 approach to incorporating PA into daily routine practice and was informed from extensive pilot work in this setting17,30 and systems change theory.1 The approach begins with identifying essential ASP characteristics that represent fundamental building blocks, which function as necessary programmatic components to achieving full integration of PA promotion strategies for the eventual achievement of PA policies. This approach departs from traditional intervention models that are based on a predefined package of intervention components all provided identically to those individuals or settings allocated to a treatment condition.31 STEPs recognizes that each ASP is unique and, therefore, will require some similar and some different resources/strategies to achieve the PA policies (i.e., there is no “one size fits all” intervention). The approach taken in STEPs is one where some degree of local site-level tailoring occurs that is both responsive and adaptive to the characteristics of each ASP.32 This assists with the local relevance of the PA promotion strategies, and subsequent uptake/integration of them within daily practice. STEPs is designed so that any one ASP can enter anywhere along the continuum, with the understanding that some ASPs will enter at a lower level indicating the need for greater technical assistance to achieve the PA policies versus those programs that enter at a higher level. STEPs was informed from a systems framework for translating childhood obesity policies into practice in ASPs,1 the principles of community-based participatory research,33 and adaptive interventions.29

The unique characteristics of the STEPs intervention are that it consisted of a primary focus on the ASP leader and worked with them to develop programmatic capacity, in the form of high-quality schedules that included PA opportunities every day as well as clearly articulating the roles and responsibilities of staff during scheduled activity opportunities. Additionally, the staff component of STEPs, LET US Play (i.e., removal of lines, elimination of elimination, reduction in team size, getting uninvolved staff and children involved in the games, and creatively using space, equipment, and rules), focused on skill development to modify the games staff are familiar with and children enjoy playing to maximize MVPA. This departed from prior interventions where staff were provided equipment and trained to play new games or relied on ASP leaders and staff to develop their own strategies.8-10,12,14-16

Technical assistance for STEPs 1–4 focused on professional development training targeting ASP leaders, those individuals responsible for daily operations of the program, to develop high-quality schedules including daily offerings of PA. The workshop consisted of working with ASP leaders to develop a 1–2-week rotating schedule that incorporated the following descriptive information: time that activity occurs, indication of scheduled activity, location activity takes place, equipment/materials required to conduct activity, and staff responsible for delivering the activity. These workshops focused both on scheduling PA and non-PA (e.g., enrichment) activities. Consistent with the California After School Physical Activity Guidelines, each ASP was asked to schedule a minimum of 60 minutes/day for PA opportunities.4 The workshop occurred during summer 2013 and lasted approximately 3 hours, depending on the amount of assistance required. For organizations operating two or more programs, a single workshop was provided for the ASP leaders at one location.

All of STEPs 1–6 occurred prior to the beginning of the school year in fall 2013. In addition, four booster sessions per ASP, each lasting for the entirety of a single ASP operating day (e.g., 3PM–6PM), occurred from September 2013 to February 2014. The booster session included a walkthrough of the ASP with the site leader to identify physical activity opportunities and LET US Play principles.17,21,28,34 Both research personnel and site leaders and staff convened a 20–30-minute meeting immediately after the end of the ASP to discuss areas that were consistent and inconsistent with meeting the PA standards. Strategies to address challenges were agreed upon and implemented in subsequent days.

Measures

All measurements occurred during the spring (March through April) of each year. Measures took place on days when the weather was conducive for outdoor activities. This was done to ensure that inclement days were not over-represented in one condition (e.g., control group had more data collection on inclement days than the intervention group). Consistent with previously established protocols, each ASP was visited for PA data collection on four non-consecutive, unannounced days Monday through Thursday during each spring.6,27,35,36 Fridays were not assessed because children typically did not have homework over the weekend; therefore, the schedule of the ASPs was altered in comparison to the schedule of activities occurring on all other weekdays. An additional 1–2 days, depending on the enrollment size of the ASP, were also used to collect child-level information. Child demographics were self-reported, and standing height and weight were measured using standard protocols with children wearing light clothing.37

The primary PA and sedentary behavior outcome was derived via accelerometry. All children attending an ASP on the days of unannounced measurement had an opportunity to wear the ActiGraph GT3X+ for up to 4 days. The accelerometers were distilled using 5-second epochs to account for the intermittent and sporadic nature of children’s PA38 and to improve the ability to capture the transitory PA patterns of children.39,40 Upon arrival to the programs, children were fitted with an accelerometer and the arrival time was recorded (monitor time on). Research staff continuously monitored the entire ASP for compliance in wearing the accelerometers. Before a child departed from a program, research staff removed the elastic belt and recorded the time of departure (monitor time off). Children wore the monitors for their entire attendance at the ASPs. This procedure was performed throughout the duration of the study.6,27,36 Cutpoint thresholds associated with moderate and vigorous activity were used to distill the PA intensity levels41 and sedentary behavior.42 Children were considered to have a valid day of accelerometer data if their total wear time (time off minus time on) was ≥60 minutes.6,27,43

Process evaluation of STEPs occurred in both intervention and control ASPs. A description of the items is presented in Table 1. Daily schedules were collected at each measurement day at baseline and post-assessment. Direct observation via the System for Observing Staff Promotion of Activity and Nutrition44 were made throughout the program operating hours where assessment of ASPs following the schedule and the types of offered PA opportunities were measured. The amount of training ASPs leaders and staff received and who delivered the trainings were assessed via interviews with ASP leaders at the end of each spring.18

Table 1.

Comparison of the Number of Afterschool Programs Implementing STEPs From Baseline to Post-Assessment

| Intervention (n=10) |

Control (n=10) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies To Enhance Practice for Physical Activity (STEPs-PA) | Baseline | Post- Assessment |

Baseline | Post- Assessment |

| 1 Schedule of daily programming | ||||

| None | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Limited detail (Defines time of occurrence with broad label for activity, no other details provided) |

7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Detailed (Clearly defines type of activity [snack, homework, enrichment, physical activity], location of occurrence, staff roles/responsibilities, necessary supplies, materials, equipment) |

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| 2 Following schedule of daily programming a | ||||

| None of the days | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Some of the days | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| Everyday | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| 3 Physical activity scheduled | ||||

| None of the days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Some of the days | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Everyday | 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

|

| ||||

| 4 Allocated time for physical activity | ||||

| ≥60 minutes of physical activity scheduled | 7 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| 5 Types of physical activity scheduled | ||||

| Girls only | 2 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| (Specific games/activities scheduled for girls - can include gender-specific

activities like dance and/or girl version of game - soccer for girls) |

||||

| Organized physical activity (Specific games/activities scheduled and led by adult) |

8 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| Free play physical activity (Children released to play ground, no structured, adult-facilitated games taking place, some children active, some not. Recommend free-play along with organized) |

10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

|

| ||||

| 6 Quantity of staff physical activity-related training | ||||

| Received no training related to physical activity skills | 4 | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| Less than 1 hour per year related to physical activity skills | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1-4 hours per year related to physical activity skills | 6 | 10 | 4 | 2 |

| More than 4 hours per year related to physical activity skills | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| 7 Quality of staff physical activity-related training (of those programs that delivered physical activity training) |

||||

| Training delivered by non-certified personnel at your program (Afterschool leader or staff without physical activity or health promotion certification) |

2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Training delivered by qualified professional (Physical educator, health promotion specialist, degree/certificate in health education field) |

4 | 10 | 4 | 0 |

If had no schedule coded as not following schedule

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in 2014. Analyses were conducted only on children with at least one valid accelerometer wear day at either baseline or post-intervention.6,27,43 Descriptive means, SDs, and percentages (for dichotomous variables) were computed separately for boys’ and girls’ demographic characteristics and for PA and sedentary behaviors. To evaluate the impact of STEPs on the standard of 30 minutes/day of MVPA (study’s primary outcome), the minutes all children at baseline and post-assessment spent in MVPA were dichotomized to represent those children who achieved (i.e., ≥30 minutes MVPA/day) and those that failed to achieve (i.e., <30 minutes MVPA/day) the PA policy. Random effects logit models, with days measured nested within children nested within ASPs, were estimated using the dichotomized 30 minutes of MVPA/day variable as the dependent variable. Full information maximum likelihood estimators were used to account for missing data at either baseline or post-intervention assessments. Logit models were estimated separately for girls and boys. The total time children attended each day was included within each model as a time-varying covariate, along with age (years), race (African American), and BMI age–sex percentile. Scheduled time for PA at baseline, change in scheduled PA time (spring 2014 minus spring 2013 scheduled activity time), total enrollment, program location/setting (school [ref], faith or community center), and ASP-level average MVPA or sedentary minutes/day were included. Fixed effects for organization were also included in the model. Secondary analyses were performed on the continuous variable of minutes of MVPA and time spent sedentary using random effects general linear models. The modeling approach for the logit models was used in these analyses. Two sets of models were estimated: (1) intent-to-treat (ITT) models using all children at baseline and post-assessment meeting the inclusion criteria; and (2) a cohort model using only children with a minimum of 1 day of valid accelerometer data at baseline and post-assessment. The matched pairs were not included in the analyses given the small number of pairs.45,46 All analyses were performed using Stata, version 13.0.

Results

Baseline and post-assessment characteristics of the ASPs and children are presented in Table 2. The number of children enrolled across the ASPs and meeting the accelerometer wear time inclusion criteria are presented in Table 2 and detailed in Figure 1. Baseline and post-assessment characteristics of the ASPs, and child-level demographics and activity levels are presented in Table 2. Unconditional model intraclass correlation coefficients at the ASP and child level were 0.13 and 0.46, respectively. The average number of days with valid PA data at baseline and post-assessment was 2.5 days, with 25% and 28%, 25% and 27%, 30% and 28%, and 20% and 18% of the children having 1, 2, 3, and 4 days of valid PA data at baseline and post-assessment, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Afterschool Programs and Children Enrolled by Treatment Condition

| Control (n=10 |

Intervention (n=10) |

Baseline between group P difference b |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Spring 2013) |

Post-Assessment (Spring 2014) |

Within group P difference |

Baseline (Spring 2013) |

Post-Assessment (Spring 2014) |

Within group P difference |

||||||

| Afterschool program characteristics |

|||||||||||

| Total kids enrolled | 870 | 864 | 895 ± 52.0 | 763 ± 45.9 | |||||||

| Boys (%) | 52.4 | 51.3 | 53.3 | 52.4 | |||||||

| Average enrollment (no. of kids, M, SD) |

87.0 ±47.8 | 86.4 ±39.5 | 0.972 | 89.5 ±52.0 | 76.3 ±45.9 | 0.006 | 0.961 | ||||

| Physical activity space (ft2) |

|||||||||||

| Indoor | 9,731 ±7,617.9 | NC | 13,835 ±17,003.5 | NC | 0.072 | ||||||

| Outdoor | 218,273 ±320,146.3 | NC | 199,243 ±229,623.6 | NC | 0.054 | ||||||

| Percentage of population in poverty, Census 2010 |

17.5 ±10.2% | NC | 13.3 ±15.6% | NC | 0.089 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Daily program length (minutes per day, M, SD) |

205.5 ±134.3 | NC | 190.5 ±128.7 | NC | 0.303 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Location (n) | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| School | 6 | NC | 3 | NC | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Faith/church | 1 | NC | 3 | NC | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Community (e.g., recreation center) |

3 | NC | 4 | NC | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Program schedule time for physical activity opportunities (minutes per day, M, SD) |

53.1 ±15.6 | 75.5 ±35.9 | <0.001 | 94.8 ±39.9 | 81.3 ±29.2 | <0.001 | 0.007 | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Child characteristics | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Race/Ethnicity (%) |

0.952 | 0.091 | <0.001 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| White non- Hispanic |

48.4 | 46.8 | 64.6 | 59.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| African American |

44.7 | 45.5 | 29.7 | 34.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Other | 6.9 | 7.7 | 5.7 | 6.7 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Age (years, M, SD) |

8.1 ±1.8 | ±7.9 ±1.9 | 0.410 | 7.9 ±1.8 | 7.9 ±1.8 | 0.954 | 0.394 | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| BMI (%) | 0.156 | 0.344 | <0.001 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| <85th percentile |

59.0 | 62.8 | 71.5 | 68.2 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| >85th percentile, <95th percentile |

22.1 | 21.3 | 20.0 | 21.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| ≥95th percentile |

19.0 | 15.9 | 8.5 | 10.8 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Children assessed via accelerometry |

Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Number of children wearing accelerometer |

357 | 299 | 352 | 349 | 370 | 334 | 380 | 294 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Avg number of days |

2.7 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Percentage of total enrollment (both boys and girls) |

75.4 | 81.1 | 78.7 | 88.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Number of children meeting accelerometer inclusion criteria a |

339 | 288 | 337 | 330 | 352 | 318 | 354 | 273 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Avg number of days |

2.6 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.3 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Percentage of total enrollment (both boys and girls) |

72.1 | 77.2 | 74.9 | 82.2 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Physical activity levels (minutes per day, M, SD) |

Boys | Girls | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Sedentary | 68.5 | ±23.9 | 77.2 ±27.7 | 64.0 ±28.6 | 74.0 ±29.0 | 60.7 | ±17.9 62.5 ±19.0 | 52.3 ±21.7 | 58.9 ±22.1 | 0.103 | 0.030 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Light PA | 43.6 | ±15.7 | 44.1 ±15.5 | 44.1 ±18.0 | 46.0 ±18.0 | 41.3 | ±13.0 39.5 ±14.8 | 43.2 ±15.3 | 40.8 ±15.6 | 0.444 | 0.171 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Moderate PA | 11.6 | ±6.0 | 9.4 ±4.4 | 11.8 ±5.9 | 9.8 ±5.1 | 12.4 | ±5.0 9.3 ±4.6 | 13.7 ±6.6 | 10.5 ±5.9 | 0.813 | 0.877 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Vigorous PA | 11.9 | ±7.9 | 8.4 ±5.7 | 11.8 ±7.9 | 8.8 ±5.8 | 12.4 | ±6.5 8.6 ±5.3 | 13.4 ±8.4 | 10.0 ±6.7 | 0.897 | 0.907 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Moderate-to- Vigorous PA |

23.5 | ±13.3 | 17.9 ±9.5 | 23.6 ±13.0 | 18.7 ±10.2 | 24.8 | ±10.7 18.0 ±9.3 | 27.2 ±14.0 | 20.5 ±11.8 | 0.982 | 0.989 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Total time in attendance |

135.6 | ±43.4 | 139.1 ±43.7 | 131.7 ±44.0 | 138.7 ±42.8 | 126.7 | ±35.3 119.9 ±34.1 | 122.7 ±33.9 | 120.2 ±33.4 | 0.205 | 0.054 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Proportion achieving 30min/d of MVPA (%) |

33.1 | 16.2 | 31.3 | 14.7 | 36.1 | 16.3 | 40.9 | 21.3 | 0.993 | 0.991 | |

Accelerometer inclusion criteria wear time ≥60 minutes per day

p-value for comparison between intervention and control at baseline. Continuous variables at the ASP-level compared using two-sample t-tests; categorical variables compared using χ2 tests; child accelerometer data compared using mixed effects models accounting for days nested within children nested within ASPs

b, boys; g, girls; NC, no change from baseline to post-assessment; PA, physical activity

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart for recruitment, data collection, and analyses.

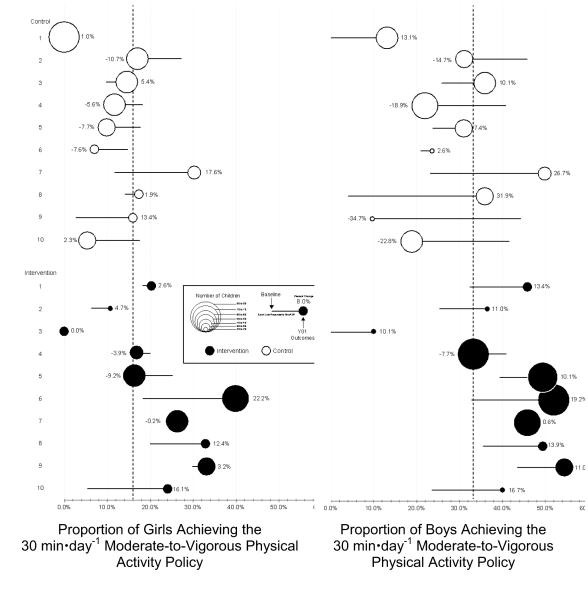

The results of the ITT and cohort models are presented in Table 3. Change in the proportion of children meeting the 30 minutes/day of MVPA policy for each ASP for intervention and control, by gender, are presented in Figure 2. Overall, the ITT indicated that the proportion of boys and girls achieving the 30 minutes/day of MVPA policy increased by 7.3% (95% CI=1.4%, 13.1%) and 6.8% (95% CI=1.6%, 12.1%), respectively, compared to boys and girls attending control ASPs. This translated into ORs of 2.26 (95% CI=1.35, 3.80) and 2.85 (95% CI=1.43, 5.68) for meeting the guideline while attending the program after 1 year of intervention. Boys and girls attending intervention ASPs increased the minutes/day spent in MVPA by 4.0 (95% CI=2.2, 5.8) and 2.7 (95% CI=1.3, 4.2), respectively, compared to boys and girls attending control ASPs. Only boys attending intervention ASPs decreased the number of minutes spent sedentary by 5.1 (95% CI= –7.9, –2.4) minutes/day. Similar findings were observed for the cohort of boys and girls measured at both baseline and post-assessment.

Table 3.

Model Estimated Change in Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity and Time Spent Sedentary From Baseline to Post-Assessment

| Proportion of children achieving the 30 min-day−1

of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity policy |

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (min-day−1) |

Time spent sedentary (min-day−1) |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within group |

Between group |

Within group |

Between group |

Within group |

Between group |

|||||||||||||||||

| n | 2013 | 2014 | Δ | Δ | (95% CI) | OR a |

(95% CI) | 2013 | 2014 | Δ | Δ a | (95% CI) | 2013 | 2014 | A | Δ a | (95% CI) | |||||

| Intent-to-treat | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boys | 1,050 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | 527 | 34.2% | 41.6% | 7.4% | 7.3% | (1.4% | 13.1%) | 2.2 6 | (1.35 | 3.80) | 24.5 | 27.8 | 3.3 | 4.0 | (2.2, | 5.8) | 64.8 | 58.4 | −6.4 | 5.1 | (−7.9, | 2.4) |

| Control | 523 | 32.6% | 32.8% | 0.2% | 23.2 | 23.9 | 0.7 | 62.2 | 60.5 | −1.6 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Girls | 940 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | 445 | 16.7% | 21.4% | 4.7% | 6.8% | (1.6% | 12.1%) | 2.8 5 | (1.43 | 5.68) | 18.6 | 20.4 | 1.8 | 2.7 | (1.3, | 4.2) | 71.8 | 69.0 | −2.8 | 2.5 | (−5.2, | 0.2) |

| Control | 495 | 16.6% | 14.5% | −2.1% | 17.9 | 18.1 | 0.2 | 68.6 | 67.2 | −1.4 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cohort | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boys | 307 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | 183 | 35.7% | 45.6% | 9.9% | 8.6% | (1.0% | 16.2%) | 2.2 3 | (1.44 | 7.74) | 24.1 | 28.1 | 4.0 | 4.1 | (1.9, | 6.2) | 65.6 | 58.2 | −7.3 | 6.1 | (−9.5, | 2.7) |

| Control | 124 | 31.3% | 32.6% | 1.3% | 23.7 | 24.3 | 0.6 | 63.6 | 62.2 | −1.4 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Girls | 304 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | 149 | 17.0% | 22.8% | 5.8% | 7.9% | (0.8% | 15.1%) | 3.3 4 | (1.44 | 7.74) | 18.6 | 20.3 | 1.7 | 3.1 | (1.1, | 5.0) | 72.0 | 68.2 | −3.8 | 4.1 | (−7.7, | 0.5) |

| Control | 155 | 14.2 % |

12.0 % |

−2.2% | 17.5 | 17.5 | 0.0 | 68.6 | 67.5 | −1.1 | ||||||||||||

Estimates adjusted for total daily wear time, scheduled physical activity opportunities at baseline, change in scheduled physical activity opportunities, age (years), race (White non-Hispanics vs. Other), BMI percentile, total enrollment, site-level baseline moderate-to-vigorous physical activity or time spent sedentary, percentage of population in poverty based on the 2010 Census, the amount of indoor and outdoor used physical activity space (ft2), and a fixed effect for organization.

Figure 2.

Change in the proportion of girls and boys for each afterschool program from baseline (spring 2013) to 1 year post-assessment (spring 2014). Note: The figure illustrates the proportion of girls and boys meeting the 30min MVPA/day Policy at baseline and post-assessment. Several programs, both in the intervention and control groups, decrease the proportion of girls or boys meeting the policy goal. The size of the circles corresponds with the number of girls or boys measured in the afterschool program.

At post-assessment, six intervention ASPs increased the proportion of boys achieving the MVPA guideline to ≥45% compared to one control ASP, while three intervention ASPs increased the proportion of girls achieving MVPA guideline to ≥30% compared to no control ASPs (Figure 2). The median relative change (change [spring 2014 minus spring 2013] divided by baseline) in the proportion of boys and girls achieving the MVPA guideline was 39.9% and 12.6% for intervention ASPs, respectively, compared to 21% and – 9% for boys and girls attending control ASPs, respectively. At baseline, intervention ASPs scheduled a greater amount of time for PA (53 vs 95 minutes/day). At post-assessment, control ASPs increased scheduled activity opportunities by 22 minutes/day (average of 75 minutes/day), whereas intervention ASPs decreased scheduled activity opportunities by 13.5 minutes/day (average of 81 minutes/day).

Discussion

Across the nation, ASPs struggle to meet PA-related policy implementation goals.6,7 This group RCT evaluated the STEPs multistep adaptive intervention designed to increase the proportion of children achieving the 30 minutes/day of MVPA policy goal for ASPs. The intervention resulted in an overall increase of 7%–9% of children achieving the MVPA policy, with four ASPs in the intervention having approximately 50% of the boys and three ASPs having approximately 30% of girls accumulating half of their daily MVPA recommendation during the program, compared to only a single ASP for boys and none of the ASPs for girls in the control group. These findings indicate that the evaluated intervention can assist ASPs in improving the PA environment in their programs, which leads to a substantial number of children meeting national and state PA policies.

The intervention builds upon prior studies by addressing major barriers ASPs face when attempting to improve children’s PA. These include insufficient staff training and an absence of skill development to create activity-friendly environments.8-11,15,16 The STEPs intervention was developed utilizing a mixture of strong theoretic elements1,28 complimented by extensive on-the-ground experience working with ASP partners. This resulted in an intervention that identified foundational components of delivering a high-quality program on a daily basis, such as creating schedules that articulate staff roles/responsibilities and activities to play, which were augmented with skill development of staff to maximize PA during scheduled activity time.17 The intervention does not require staff to learn a large number of new, unfamiliar games, but rather instructs them to take the games they, and the children, already know and maximize the amount of PA children accumulate when playing. Prior studies have found that staff utilize a limited number of games provided in prepackaged curricula.14 An unpublished review of 11 existing PA curricula found that, on average, 240 games are provided (range, 55–600 games). This volume of games, without appropriate PA training, likely dampens the effectiveness of such curricula and suggests that future studies need to focus on skill development as much as, if not more than, introducing new games.

This intervention and corresponding findings are even more important given the substantial diversity represented in the sample of ASPs. Prior studies have focused on programs delivered solely within YMCA facilities or schools and enrolled small numbers of children.8-11,15 The programs recruited in this study were deliberately selected to represent a large range of ASP types, including those operating within faith settings, community recreation centers, and schools. The programs also ranged considerably in size based on enrollment (range, 30–162 children attending each day) and indoor/outdoor space, as well as diversity in ethnic composition with, for example, a single intervention ASP operating on a Native American reservation. Although all the ASPs operated within a single southeastern state, the diversity of ASPs improves the generalizability of the intervention effects and suggests that ASPs across the nation can utilize STEPs to help them work toward achieving PA policy goals.

It is important to note that several of the ASPs in the control condition substantially increased the proportion of boys, girls, or both achieving the 30 minutes of MVPA/day policy (Figure 1). Program observations revealed that these ASPs began allocating more time for PA each day compared to baseline or were facilitating activities not aligned with best practices, such as military-type drills (e.g., line runs); or began to facilitate activities led by untrained staff versus allowing children the option to be active for extended periods of time, which substantially decreased boys’ MVPA, yet had a beneficial effect on girls’ MVPA. Likewise, not all intervention ASPs beneficially changed. In intervention ASP 4, decreases were observed for both boys and girls. In review of daily schedules, this ASP had reduced its total activity opportunities from 150 minutes/day to 65 minutes/day. By contrast, intervention ASPs 6 and 7 also decreased daily scheduled activity time by 35 and 45 minutes/day, respectively; yet, this decreased opportunity resulted in some of the largest increases in boys and girls meeting the 30 minutes of MVPA/day policy goal. These findings suggest that the reduced time for activity opportunities was offset by the intervention, with staff maximizing child PA during scheduled activity time—one of the primary components of the STEPs intervention.

Based on the process data, STEPs was effective at assisting some of the intervention ASPs develop schedules, follow those schedules, and program more girls-only opportunities (Table 1). The limited changes observed in the intervention ASPs related to scheduling were due to changes in the number of enrolled children and subsequent structure of the program mid-year or schedule disruption because of events outside the ASP leader’s control (e.g., school concerts, construction). Changes were also observed in the control ASPs on these same process indicators. However, these self-initiated changes by the control ASPs were less effective at increasing PA compared to the intervention ASPs. This is likely because of the lack of training on creating activity-friendly environments received by the control ASPs and, of those that did receive training, the lack of quality.

There are a number of strengths of the current study. First, this study represents one of the largest studies conducted to date in terms of the number of ASPs and children evaluated via accelerometry. Secondly, the group RCT, diverse ASPs, baseline equivalence on primary outcome (30 minutes of MVPA) and enrollment size, as well as the majority of other demographic characteristics support the casual inferences corresponding to the intervention’s impact on MVPA. It is recognized that baseline differences between intervention and control ASPs in total time in attendance, proportion of African Americans, and BMI status existed. Prior studies6,7 have indicated that African American children are more likely to meet existing policy guidelines for MVPA and that BMI status is not associated with achieving an MVPA policy recommendation. These were covaried in the analyses to mitigate their influence in the statistical models. Additionally, total daily activity was not collected; therefore, it is unclear if these changes influenced (either upwardly or downwardly) the amount of activity children accumulated outside of the ASPs. Previous studies investigating this, however, have not found that children compensate (i.e., reduce) their activity across other settings when exposed to an intervention.47,48 Nevertheless, future studies should attempt to collect total daily PA to evaluate the contribution of ASP MVPA to total daily MVPA. Finally, none of the ASPs were able to fully meet the 30-minute/day MVPA goal—100% (i.e., all) of children meeting. For obvious reasons,7,17 this is not a realistic goal but presents a target all ASPs should strive toward. A goal of one of two children meeting the policy benchmark would seem more realistic; however, only a few of the ASPs in this study approached this goal.

Conclusions

The results of this group RCT suggest that the STEPs approach can assist ASPs toward meeting PA policy goals. However, work is required to identify additional ways to increase the amount of MVPA children attending ASPs accumulate, with a concerted focus on the identification of effective strategies to use with girls.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH under award number R01HL112787. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT02144519.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Beets MW, Webster C, Saunders R, Huberty JL. Translating policies into practice: a framework for addressing childhood obesity in afterschool programs. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(2):228–237. doi: 10.1177/1524839912446320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524839912446320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.America After 3 PM: A Household Survey on Afterschool in America. Afterschool Alliance; Washington, DC: 2009. www.afterschoolalliance.org/publications.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beets MW, Wallner M, Beighle A. Defining standards and policies for promoting physical activity in afterschool programs. J Sch Health. 2010;80(8):411–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00521.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.California Department of Education . California After School Physical Activity Guidelines. California Department of Education; Sacramenta, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. DHHS . 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. U.S. DHHS; Washington, D.C.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beets MW, Rooney L, Tilley F, Beighle A, Webster C. Evaluation of policies to promote physical activity in afterschool programs: are we meeting current benchmarks? Prev Med. 2010;51(3-4):299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.07.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beets MW, Shah R, Weaver RG, Huberty J, Beighle A, Moore JB. Physical Activity in Afterschool Programs: Comparison to Physical Activity Policies. J Phys Act Health. 2014 doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2013-0135. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Dzewaltowski DA, Rosenkranz RR, Geller KS, et al. HOP'N after-school project: an obesity prevention randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gortmaker SL, Lee RM, Mozaffarian RS, et al. Effect of an After-School Intervention on Increases in Children's Physical Activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(3):450–457. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182300128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182300128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrick H, Thompson H, Kinder J, Madsen KA. Use of SPARK to promote after-school physical activity. J Sch Health. 2012;82(10):457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00722.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iversen CS, Nigg C, Titchenal CA. The impact of an elementary after-school nutrition and physical activity program on children's fruit and vegetable intake, physical activity, and body mass index: Fun 5. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(7 Suppl 1):37–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nigg C, Battista J, Chang JA, Yamashita M, Chung R. Physical activity outcomes of a pilot intervention using SPARK active recreation in elementary after-school programs. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2004;26:S144–S5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nigg CR, Geller K, Adams P, Hamada M, Hwang P, Chung R. Successful Dissemination of Fun 5: A Physical Activity and Nutrition Program for Children. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(3):276–285. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0120-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13142-012-0120-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharpe EK, Forrester S, Mandigo J. Engaging Community Providers to Create More Active After-School Environments: Results From the Ontario CATCH Kids Club Implementation Project. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(Suppl 1):S26–31. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.s1.s26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelder S, Hoelscher DM, Barroso CS, Walker JL, Cribb P, Hu S. The CATCH Kids Club: a pilot after-school study for improving elementary students' nutrition and physical activity. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(2):133–140. doi: 10.1079/phn2004678. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/PHN2004678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastmann TJ, Bopp M, Fallon EA, Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski DA. Factors Influencing the Implementation of Organized Physical Activity and Fruit and Vegetable Snacks in the HOP'N After-School Obesity Prevention Program. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.06.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Moore JB, et al. From Policy to Practice: Strategies to Meet Physical Activity Standards in YMCA Afterschool Programs. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3):281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajja R, Beets MW, Huberty J, Kaczynski AT, Ward DS. The Healthy Afterschool Activity and Nutrition Documentation Instrument. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beets MW, Huberty J, Beighle A, et al. Impact of policy environment characteristics on physical activity and sedentary behaviors of children attending afterschool programs. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):296–304. doi: 10.1177/1090198112459051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1090198112459051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Webster C, Beighle A, Huberty J. A Conceptual Model for Training After-School Program Staffers to Promote Physical Activity and Nutrition. J Sch Health. 2012;82(4):186–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00685.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Saunders R, Webster C, Beighle A. A Comprehensive Professional Development Training’s Effect on Afterschool Program Staff Behaviors to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. J Public Health Manag Pract. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a1fb5d. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beets MW. Enhancing the translation of physical activity interventions in afterschool programs. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2012;6(4):328–341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1559827611433547. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bloom HS, Bos JM, Lee SW. Using cluster random assignment to measure program impacts. Statistical implications for the evaluation of education programs. Eval Rev. 1999;23(4):445–469. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9902300405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0193841X9902300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murrary DM. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webber LS, Catellier DJ, Lytle LA, et al. Promoting physical activity in middle school girls: Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens J, Murray DM, Catellier DJ, et al. Design of the trial of activity in adolescent girls (TAAG) Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26(2):223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.12.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beets MW, Huberty J, Beighle A. Physical Activity of Children Attending Afterschool Programs Research- and Practice-Based Implications. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(2):180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Turner-McGrievy G, et al. Making Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Policy Practice: The Design and Overview of a Group Randomized Controlled Trial in Afterschool Programs. Contemp Clin Trials. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.05.013. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prev Sci. 2004;5(3):185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:PREV.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huberty JL, Beets MW, Beighle A, Balluff M. Movin After School: A community-based support for policy change in the afterschool environment. Childhood Obesity. 2010;6(6):337–341. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):171–181. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how "out of control" can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1561–1563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Webster C. LET US Play: Maximizing children’s physical activity in physical education. Strategies. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beets MW, Beighle A, Bottai M, Rooney L, Tilley F. Pedometer-determined step count guidelines for afterschool programs. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(1):71–77. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Moore JB, et al. From Policy to Practice: Strategies to Meet Physical Activity Standards in YMCA Afterschool Programs. Am J Prev Med. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.012. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity and Trends in Body Mass Index Among US Children and Adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey RC, Olson J, Pepper SL, Porszaz J, Barstow TJ, Cooper DM. The level and tempo of children's physical activities: An observational study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1033–1041. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199507000-00012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baquet G, Stratton G, Van Praagh E, Berthoin S. Improving physical activity assessment in prepubertal children with high-frequency accelerometry monitoring: a methodological issue. Prev Med. 2007;44(2):143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.10.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vale S, Santos R, Silva P, Soares-Miranda L, Mota J. Preschool children physical activity measurement: importance of epoch length choice. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2009;21(4):413–420. doi: 10.1123/pes.21.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak KS, McMurray RG. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(14):1557–1565. doi: 10.1080/02640410802334196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02640410802334196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(7):875–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trost SG, Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski D. Physical activity levels among children attending after-school programs. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(4):622–629. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318161eaa5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318161eaa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Webster C, Huberty J. System for Observing Staff Promotion of Activity and Nutrition (SOSPAN) J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(1):173–185. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2012-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donner A, Taljaard M, Klar N. The merits of breaking the matches: a cautionary tale. Stat Med. 2007;26(9):2036–2051. doi: 10.1002/sim.2662. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sim.2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diehr P, Martin DC, Koepsell T, Cheadle A. Breaking the matches in a paired t-test for community interventions when the number of pairs is small. Stat Med. 1995;14(13):1491–1504. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780141309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baggett CD, Stevens J, Catellier DJ, et al. Compensation or displacement of physical activity in middle-school girls: the Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls. Int J Obes. 2010;34(7):1193–1199. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodman A, Mackett RL, Paskins J. Activity compensation and activity synergy in British 8-13 year olds. Prev Med. 2011;53(4-5):293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.07.019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]