Abstract

Adenylyl cyclases (ACs) are a group of widely distributed enzymes whose functions are very diverse. There are nine known transmembrane AC isoforms activated by Gαs. Each has its own pattern of expression in the digestive system and differential regulation of function by Ca2+ and other intracellular signals. In addition to the transmembrane isoforms, one AC is soluble and exhibits distinct regulation. In this review, the basic structure, regulation and physiological roles of ACs in the digestive system are discussed.

Keywords: Adenylyl cyclase, Exocrine pancreas, Liver, Salivary gland, Stomach, Intestine

1. Introduction

Adenylyl cyclases (ACs) catalyze the conversion of ATP to cAMP and pyrophosphate. The reaction occurs in a single step where the oxygen on 3′ hydroxyl group of ATP nucleophilically attacks the α-phosphate forming a phosphodiester bond and cleaving a pyrophosphate group [1]. Once generated, cAMP acts as a second messenger through two primary pathways: (1) by promoting proteins phosphorylation by activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) or (2) by activating exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac). PKA is a heterotetramer composed of two subunits: a catalytic subunit that contains the enzyme’s active site, and an ATP-binding domain, as well as a regulatory subunit that binds cAMP [2]. PKA phosphorylates a wide range of proteins at serine and threonine residues. The targets can be enzymes such as phosphorylase kinase, ion channels including cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), chromosomal proteins such as histone H1, and transcription factors including cAMP response element binding proteins (CREBs) [3]. In rat pancreatic acini, PKA induces a potentiation of Ca2+-dependent amylase secretion [4]. In dispersed rat submandibular and parotid cells, PKA triggers exocytosis and phosphorylates a 26-kDa integral membrane protein [5]. CREB phosphorylation is observed upon PKA activation in both parotid acini [6] and pancreatic acini [7,8]. Epac, like PKA, has two subunits: a catalytic subunit that contains a CDC25-homology domain, a REM (Ras Exchange Motif) and a RA (Ras Association) domain, as well as a regulatory subunit that binds cAMP [9]. Epac is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the small G proteins Rap1 and Rap2. In both pancreatic acini and parotid acini, Epac activation leads to increased amylase secretion [7,10,11].

Ten AC isoforms have been identified: nine isoforms are transmembrane and activated by Gαs. The single “soluble” AC10 isoform that lacks the transmembrane domains, is insensitive to Gαs, and more closely resembles the cyanobacterial AC enzymes than the transmembrane ACs [12].

The functions of ACs in the heart, kidney and brain have been well described, but are lacking for digestive tract [13–15]. In this manuscript, we provide a comprehensive review of the structure of a single AC, the regulation of AC isoforms, as well as their physiological and pathophysiological roles in the digestive system.

2. Structure of adenylyl cyclase

At least 9 transmembrane AC isoforms (AC1, AC2, AC3, AC4, AC5, AC6, AC7, AC8 and AC9), two splice variants of AC8 and one soluble AC isoform (AC10) have been cloned and characterized in mammals.

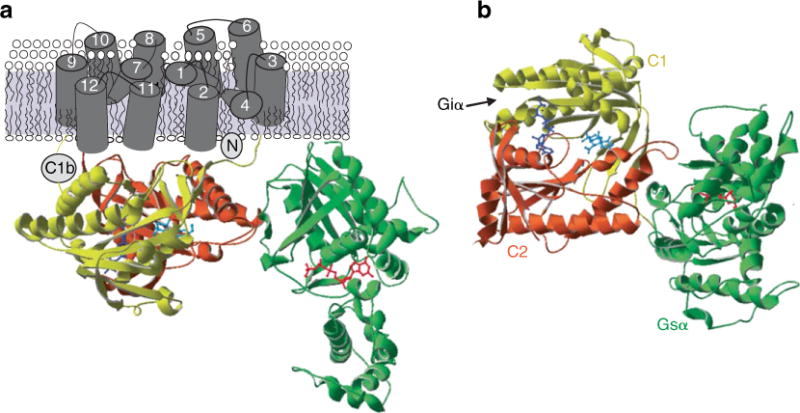

The transmembrane AC isoforms share a large sequence homology in the primary structure and similar predicted three-dimensional structure. Each transmembrane AC isoform is coded by a different gene located in a different chromosome, with the exception of humans which have two genes that encode AC7 and AC9 on chromosome 16 [16]. AC structure can be divided in five major domains: 1) the NH2 terminus, 2) the first transmembrane cluster (TM1), 3) the first cytoplasmic loop composed of C1a and C1b, 4) the second transmembrane cluster (TM2) with extracellular N-glycosylation sites, and 5) the second cytoplasmic loop composed of C2a and C2b (Fig. 1). The transmembrane regions are composed of six membrane-spanning helices, which cross the plasma membrane 12 times in 2 clusters of 6 TM domains (TM1 and TM2), whose function is to keep the enzyme anchored in the membrane. The cytoplasmic regions C1 and C2 are approximately 40 kDa each and can be further subdivided into C1a, C1b, C2a, and C2b. Both C1a and C2a are highly conserved catalytic ATP-binding regions [17], which dimerize to form a pseudosymmetric enzyme, which forms the catalytic site. ATP binds at one of two pseudosymmetric binding sites of the C1–C2 interface. A second C1 domain subsite includes a P-loop that accommodates the nucleotide phosphates and two conserved acid residues that bind to ATP through interaction with two Mg2+; one Mg2+ contributes to catalysis, whereas the second one interacts with nucleotide β- and γ-phosphates from substrate binding and possibly for leaving group stabilization. Both C2a and C2b are less conserved than the C1 domain [17,18]. These two cytoplasmic regions are responsible for regulation by the G-proteins subunits α and βγ and specific intracellular signals [19]. The C1b domain is the largest domain and contains several regulatory sites, and has a variable structure across the isoforms. The C2b domain is essentially non-existent in many isoforms, and has not yet been associated with a function [20].

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of adenylyl cyclase. a) The figure shows the catalytic domains of mammalian AC (C1 and C2) with Gαs (green) and Gαi. The location of forskolin (cyan) and P-site inhibitor (dark blue) is also appreciated. b) An alternate view from cytoplasmic side, showing forskolin and catalytic site. The interaction site of Giα with C1 domain is indicated by an arrow. This figure was obtained with permission from [13].

The soluble AC is the most divergent in its sequence and is similar to ACs found in cyanobacteria. Soluble AC was originally isolated from the testis [12,21,22] and has been found in other tissues such as pancreas [23–25]. There are several splice variants but the two resulting in the 186-kDa (the full-length form: sACfl) and 48-kDa (the truncated form: sACt) proteins are the most studied [26]. sACfl consists of two catalytic subunits: a consensus P-loop (ATP/GTP-binding site), and a leucine zipper sequence (dimerization/DNA binding domain). In contrast, sACt consists only of the two catalytic subunits and is reported to be at least ten-fold more active than sACfl [27]. The catalytic domains of the enzymes are more closely related to those of cyanobacteria and mycobacteria than they are to transmembrane AC isoforms [12,27]. A third variant of soluble AC has recently been described, which arises from an alternate start site preceding exon 5 and is found in somatic tissues [28]. Soluble AC can be found in the cytosol, but has also been found associated with specific organelles including the nucleus, mitochondria, and microtubules [29].

3. Regulation of AC activity

Once a stimulatory ligand is bound to the G protein coupled receptors (GPCR), it activates a transmembrane heterotrimeric G protein composed by three subunits: a guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound α subunit and a βγ heterodimer. Activation requires the exchange of bound GDP for guanosine triphosphate (GTP), which induces a conformational change, and thereby, a dissociation of the α subunit from the βγ heterodimer. The binding site on AC for the G protein α subunits is an important part of the structure that allow it to function: when the α subunit of Gs protein binds to its binding site, the binding sites for ATP are exposed and AC can then catalyze the transformation of ATP to cAMP. By contrast, when the α subunit of Gi protein binds to its binding site, the enzyme activity of AC is inhibited. Whereas the Gs protein α subunit binding site is located in the outside of C2 and the NH2-terminus of C1, the α subunit of Gi protein binding site is located in the C1 domain [30].

The activity of AC can be also regulated by PKA, PKC, and Ca2+. Based on regulatory properties, transmembrane ACs are classified into four groups with the following essential regulatory properties (see Table 1 for details):

-

–

Group I: Ca2+/calmodulin-stimulated AC1, AC3, AC8;

-

–

Group II: Gβγ-stimulated and Ca2+-insensitive AC2, AC4, AC7;

-

–

Group III: Gαi/Ca2+/PKA-inhibited AC5, AC6;

-

–

Group IV: forskolin/Ca2+/Gβγ-insensitive AC9.

Table 1.

Regulatory properties of adenylyl cyclase isoforms.

| AC isoform | MW (kDa)a (mouse) | Gαs | Gαi | Gβγ | FSK | Calcium | Protein Kinases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I: | Calcium–stimulated | ||||||

| AC1 | 123.37 | (+) | (–) | (–) | (+) | (+, CaM) or (–, CaM kinase IV) | (+, PKCα) |

| AC3 | 129.08 | (+) | (–) | (–) | (+) | (+, CaM) or (–, CaM kinase II) | (+, PKCα) |

| AC8 | 140.1 | (+) | (–) | (–) | (+) | (+, CaM) | (=) |

|

| |||||||

| Group II: | Calcium–insensitive | ||||||

| AC2 | 123.27 | (+) | (=) | (+) | (+) | (+, PKCα) | |

| AC4 | 120.38 | (+) | (=) | (+) | (+) | (+, PKC) or (–, PKCα) | |

| AC7 | 122.71 | (+) | (=) | (+) | (+) | (+, PKCδ) | |

|

| |||||||

| Group III: | Calcium–inhibited | ||||||

| AC5 | 139.12 | (+) | (–) | (+, β1γ2) | (+) | (–, < 1 μM) | (–, PKAb) (+, PKCα/ζ) |

| AC6 | 130.61 | (+) | (–) | (+, β1γ2) | (+) | (–, < 1 μM) | (–, PKAb, PKCδ, ε) |

|

| |||||||

| Group IV: | |||||||

| AC9 | 150.95 | (+) | (–) | (=) | (=) or (+,weak) |

(+, CaM kinase II) (–, calcineurin) |

(–, novel PKC) |

|

| |||||||

| AC10 | 186/48c | (=) | (=) | (=) | (=) | Calcium–stimulated | (=) |

Regulatory properties of mammalian ACs. (+): AC activity is stimulated; (−): AC activity is inhibited; (=): AC activity is not modified. Data taken from [12,15,139,140].

The molecular weight (MW) data was obtained from PhosphoSitePlus from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.

AC6 is directly phosphorylated by PKA at Ser674, and thereby inhibited [141].

186 kDa: the full length form and 48 kDa: the truncated form [26].

The soluble AC, unlike the transmembrane ACs, is insensitive to hormones, G proteins and forskolin, a diterpene extracted from the root of the plant Coleus forskohlii that directly activates all isoforms of transmembrane ACs except AC9 [12]. Soluble AC was originally identified as a sensor [31]. However, later studies revealed that soluble AC can also be activated by divalent cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+ and Mn2+, as well as cellular ATP levels [32–35] (see Table 1 for details). Soluble AC plays a role as a metabolic and intracellular pH sensor because soluble AC can be activated by , Ca2+ and ATP [35]. Like transmembrane AC isoforms [36–39], an increase in cAMP induced by soluble AC activates both PKA [40] and Epac/Rap1 pathways [41,42].

4. Role of AC in the regulation of digestive system

The digestive system is constituted by two main groups of organs: 1) those of the gastrointestinal tract or gut, and 2) the accessory digestive organs. The gastrointestinal tract is the continuous muscular tube that courses through the body from the mouth to the anus. Gastrointestinal tract organs include the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The accessory digestive organs are the teeth, tongue, gallbladder, salivary glands, liver and pancreas. This review highlights the expression profile of AC isoforms in digestive organs, as well as the roles of ACs in physiological and pathophysiological processes of the digestive system.

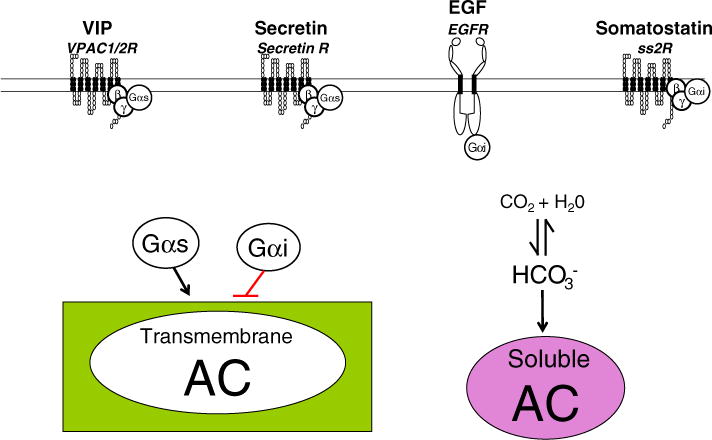

4.1. Role of AC in the regulation of exocrine pancreatic function

The exocrine pancreas is predominantly composed of acinar cells arranged in acini, which release stored digestive enzymes into a duct, and a ductular system, which is lined by epithelial cells that release a -rich fluid to neutralize the acidic chyme from the stomach. In the exocrine pancreas, AC activation mainly occurs after the stimulation by the two secretagogues vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and secretin, which mediated by activation of VPACs and secretin receptors, respectively, activate Gαs. Somatostatin, which activates Gαi through SS2R receptor activation, inhibits the activity of AC [43,44] (Fig. 2). Although the role of cholecystokinin (CCK) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) remains unknown, some evidence supports their participation in the regulation of AC activity [45–47]. The principal function of AC in the exocrine pancreas is to stimulate the secretion of -rich fluid from pancreatic duct epithelial cells. Activation of AC induces an increase in cAMP levels and, in turn, activation of PKA. In the apical membrane of the duct cells, the phosphorylation of CFTR by PKA enhances channel chloride conductance into the duct lumen, which depolarizes both luminal and basolateral membranes. Depolarization of the basolateral membrane increases the driving force of an electrogenic Na+– co-transporter on the basolateral membrane leading to the entry of , which is then secreted at the apical membrane through the Cl−/ exchanger, as well as CFTR [48]. An increase in cAMP levels, on the other hand, inhibits the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) and this, like the stimulation of the apical anion exchanger, may occur through a direct physical interaction with CFTR [48]. Basolateral Cl−/ exchanger (AE) does not seem to be directly activated by cAMP pathway [49].

Fig. 2.

Intracellular mechanisms implicated in the regulation of AC activity in pancreatic exocrine cells. Activation of transmembrane AC occurs after the stimulation by VIP and secretin, which mediated by activation of VPACs and secretin receptors, respectively, activate Gαs. Both somatostatin and EGF, which activate Gαi, inhibit the activity of AC. Soluble AC is activated by . Black arrow: stimulation; red line: inhibition.

Activation of AC also induces a modest increase in amylase secretion. Earlier studies showed that forskolin stimulates pancreatic amylase secretion [50,51], as well as potentiates the response to Ca2+-dependent secretagogues such as CCK [52]. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors, such as 3-isobutyl-1-methylxantine (IBMX), increase cAMP levels and also enhance pancreatic amylase secretion induced by cAMP-dependent secretagogues [53]. The participation of AC in the regulation of amylase secretion is also supported by the fact that pertussis toxin, an inhibitor of Gi protein, increases the basal levels of cAMP and amylase secretion [45], indicating that Gi exerts a constitutively inhibitory effect in pancreatic acini. In addition to that, in rabbit pancreatic acini, pertussis toxin stimulates CCK-induced cAMP levels without affecting CCK-induced Ca2+ mobilization or amylase secretion [54]. In isolated rat pancreatic acinar cells, pretreatment with pertussis toxin does not modify CCK-stimulated intracellular Ca2+ levels or phosphoinosite hydrolysis [55].

The combination of cAMP-dependent secretagogues with low concentrations of Ca2+-dependent secretagogues shows a synergic effect on amylase secretion. For example, in isolated rat pancreatic acini both VIP and secretin potentiate amylase secretion stimulated by CCK or the cholinergic agonist carbachol [56,57]. A later study demonstrated that PKA is responsible for the modulation of Ca2+- and PKC-evoked amylase secretion in permeabilized rat pancreatic secretion [4]. Supramaximal concentrations of CCK or carbachol, by contrast, abolish VIP potentiation by inhibiting AC activity through activation of PKC [58].

4.1.1. Several AC isoforms are found in pancreatic exocrine cells

In the past years, the hypothesized AC expression profile in pancreatic exocrine cells came primary from studies that use pharmacologic stimulators and inhibitors of intracellular signals [58,59]. Recently, the expression profile of the transmembrane AC isoforms in intact mouse pancreas, isolated pancreatic acini and sealed duct fragments was establishsed [36]. Using reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis, five different transmembrane AC isoforms were able to be identified in pancreatic exocrine cells: AC3, AC4, AC6, AC9 mRNAs were expressed in isolated pancreatic acini and sealed duct fragments, whereas AC7 mRNAs was only expressed in sealed duct fragments. Using real-time quantitative PCR analysis, the relative expression of each isoform in pancreatic acini and ducts compared to the intact pancreas was assessed: isolated pancreatic acini were shown to have higher transcript levels of AC6 compared with intact pancreas, whereas isolated duct fragments were shown to have higher transcript levels of AC4, AC6 and AC7 compared with intact pancreas. Similar transcript levels of AC3 and AC9 were observed in the intact pancreas, isolated pancreatic acini and sealed duct fragments.

Soluble AC was identified in acinar cells using reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis and immunoblotting. Using a monoclonal antibody against soluble AC, the isoform was localized by immunohistochemistry below the apical region of the acinar cell in non-stimulated condition and, after treatment with the CCK analog caerulein, punctuate intracellular pattern was observed [25].

4.1.2. AC6 as a primary AC isoform in the regulation of pancreatic exocrine cells

AC6 is the primary isoform regulating the response to cAMP-dependent secretagogues in isolated pancreatic exocrine cells. Using a number of chemical stimulators and inhibitors, as well as mice deficient in AC6 [60], the study established that AC6 plays a regulatory role in the functions of pancreatic exocrine cells [36]. The effect of VIP on cAMP levels was enhanced by PKA and PKC inhibitors, as well as by a depletion of Ca2+, and not modified by stimulants including the Ca2+ agonist A23187, phorbol ester, and the cholinergic agonist carbachol, indicating that Ca2+/PKC/PKA-inhibited AC6 is likely to mediate the action of VIP. Supporting this conclusion, isolated pancreatic acini from mice with genetically deleted AC6 showed a decrease in both cAMP levels and PKA activation stimulated by cAMP-dependent secretagogues. In isolated sealed duct fragments the reduction of these parameters was even larger. As a consequence of the reduction in the cAMP/PKA pathway activity, the lack of AC6 partially reduced pancreatic amylase secretion evoked by cAMP-dependent secretagogues, whereas it almost abolished pancreatic fluid secretion in both in vivo and isolated sealed duct fragments [36]. No change in the response to VIP was observed in presence of either the calmodulin inhibitor or calcineurin inhibitor, which indicates that both the Ca2+/calmodulin-stimulated AC3 and the Ca2+/calcineurin inhibited AC9 are unlikely to participate in VIP-stimulated cAMP formation in pancreatic acini, and that Ca2+ negatively regulates the activity of AC6 in a direct-manner. Recently, the capacitive entry of Ca2+ (secondary to the emptying of the intracellular Ca2+ pool) has been proposed to play a role in regulating negatively AC6 activity [61]. Translocation of STIM1 has been required for an efficient coupling of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ depletion to AC activity [62]. On the other hand, intracellular Ca2+ from IP3-sensitive stores is unable to affect Ca2+-stimulated AC iso-forms [63].

Epac1, which has been shown to modulate cAMP-stimulated amylase secretion [7,10], is unlikely to mediate the effect of AC6. The response to the Epac1 analog 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP on pancreatic amylase secretion was not modified by the absence of AC6 [36].

Given that the inhibition of Gαi activity by pertussis toxin increases cAMP levels in rabbit pancreatic acini [54] and that AC6 is the only AC isoform regulated by Gαi, it has suggested that AC6 is present in this cell type. Because somatostatin inhibits AC through SS2R coupled to Gαi subunits [64,65], it is likely that AC6 is responsible for the inhibitory effect of somatostatin in the exocrine pancreas.

4.1.3. The protective role of soluble AC in the acute pancreatitis

The premature and intracellular activation of zymogens, particularly trypsinogen and chymotrypsinogen, within the acinar cell is an early feature of acute pancreatitis. cAMP has been found to enhance secretagogue-stimulated zymogen activation when intracellular cAMP levels were increased using membrane permeable analogs of cAMP [66,67]. This response was also observed after treatment with secretin, VIP and pituitary AC-activating peptide (PACAP) [66], whose receptors are linked to transmembrane ACs. This enhancement of activation was mediated by both PKA and Epac pathways [10]. Recently, soluble AC has been involved in the inhibition of acinar cell zymogen activation, suggesting that soluble AC has a protective effect on the acute pancreatitis [25]. The treatment with the soluble AC inhibitor KH7 enhanced caerulein-induced zymogen activation, whereas treatment with inhibited it. The two inhibitors of PKA, PKI and H-89, also increased caerulein-induced zymogen activation. The treatment with (an activator of soluble AC) also reduced caerulein-stimulated acinar cell vacuolization, an early marker of acute pancreatitis [25].

The mechanism by which soluble AC exerts its protective role is still unknown. Several mechanisms can simultaneously occur: soluble AC has been associated with CFTR activation in the corneal endothelium [68] and human airway epithelial cells [69], oxidative phosphorylation in HeLa cells [70], as well as apoptosis inhibition in corneal endothelial cell [71].

These two studies [25,66] establish a precedent by demonstrating that cAMP generated by transmembrane AC can elicit different responses in pancreatic exocrine cells than those seen with soluble AC. Whereas the stimulation of the transmembrane AC increases zymogen activation, the stimulation of soluble AC inhibits zymogen activation.

4.1.4. Roles of other AC isoforms expressed in the exocrine pancreas

The Ca2+-insensitive AC7 isoform is present in isolated sealed duct fragments, though is not present in pancreatic acini, which are cells mainly regulated by Ca2+. AC7 has been shown to participate in the synergistic effect of Gα12/13 on Gs-stimulated cAMP production in HEK cells [72]. The lack of AC7 expression in pancreatic acini is consistent with previous results which demonstrated that the expression of p115-RGS, that is a RGS domain of p115-RhoGEF and an inhibitor of Gα12/13 [73], does not modify VIP-induced cAMP production in mouse pancreatic acini [74]. AC4 is another Ca2+-insensitive isoform whose transcript levels are higher in isolated sealed duct fragments compared to the intact pancreas.

AC9 is the most divergent of the transmembrane isoforms and the only isoform not stimulated by forskolin [13,16]. AC9, present in pancreatic acini, is inhibited by calcineurin [75], a protein phosphatase activated by CCK [76,77] and involved in amylase secretion from rat pancreatic acini [78], as well as caerulein-induced intracellular pancreatic zymogen activation [79]. In addition to that, AC9 is stimulated by Ca2+/CaMKII phosphorylation [80], which is also present in pancreatic acini and activated by CCK [81].

4.2. Role of AC in the regulation of liver function

The role of AC in the liver has been studied for a number of years. In the 1960s, Sutherland and Rall discovered that epinephrine stimulates liver cells to form cAMP through AC [82,83]. Later, Sutherland and others demonstrated that cAMP generated by AC acts as a second messenger system for many hormones and neurotransmitters [82,84,85].

AC plays an important role in the intracellular mechanisms trigger by gastrointestinal hormones, neuropeptides and neurotransmitters that regulate liver physiology and cAMP-dependent protection from liver damage. The liver is composed of two epithelia cell types: hepatocytes, which initiate secretion of bile at the bile canaliculus, and cholangiocytes, which line the bile ducts and modify ductal bile during transport to the duodenum in response to a series of spontaneous and hormonal events [86,87]. Other cell types in the liver include hepatic stellate cells and Kupffer cells. The large majority of the studies evaluating AC have been performed in cholangiocytes, which we will discuss first.

4.2.1. Role of ACs in the modulation of cholangiocyte function

The biliary system, lined by cholangiocytes, forms a three-dimensional network of interconnecting ducts [85], which extend from the proximal branch called the canals of Hering to the extrahepatic ducts [88–90]. Cholangiocytes are specialized epithelial cells that regulate both the alkalinity and volume of bile [91,92]. Cholangiocyte secretion and proliferation are modulated by a number of autocrine and paracrine effectors, such as neuropeptides, neurotransmitters and gastrointestinal hormones including secretin [93,94].

In the liver, cholangiocytes are the only cell type that expresses the secretin receptor [95]. The biological action of secretin on cholangiocytes occurs through a series of coordinated events [86,88,90]. First, secretin binds to the basolateral secretin receptor of cholangiocytes causing an AC-dependent increase in cAMP triggering the activation of PKA [88,90]. PKA then phosphorylates CFTR at the apical membrane of cholangiocytes, triggering the release of Cl− [87]. The resulting Cl− gradient activates the apically located Cl−/ anion exchanger 2 (AE2) to secrete into ductal bile [96]. Elevated intracellular cAMP levels also contribute to Cl− conductance through Epac [97]. Secretin stimulated cAMP levels also regulate other important cellular functions, such as vesicular transport and the release of ATP [98–101].

Spirli and colleagues provided evidence that AC plays a key role in the regulation of biliary secretion. They demonstrated that proinflammatory cytokines stimulate the production of nitric oxide (NO) and that it triggers a reduction of bile secretion by a reactive NO species-mediated inhibition of AC [102]. Inhibition of AC resulted in a reduction of cAMP-dependent Cl− and secretion [102]. In addition, the expression of NO synthase 2 was increased in the biliary epithelium of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis [102]. A subsequent studied revealed that six transmembrane ACs (AC4–9) and soluble AC are expressed by cholangiocytes [103].

Other studies have demonstrated that several AC isoforms are localized near the primary cilia of cholangiocytes and play a key role in secretory mechanisms [97,104]. These studies elegantly showed that cholangiocyte cilia have a mechanosensory function [97,104]. In the first study, the Ca2+-inhibited AC6 was localized in the cilia [104]. In cholangiocytes, luminal fluid flow induces an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and a decrease in cAMP signaling by inducing bending of the primary cilia [104]. The flow-induced reduction of cAMP levels was due to the inhibition of AC6 by an increase in intracellular Ca2+ [104]. This finding suggests that the cilia play an important role as fluid flow sensors in the coordination of biliary bile formation [104]. This same laboratory demonstrated that the cholangiocyte primary cilia also function as a chemosensory organelle [97]. In this study, AC4, AC6 and AC8, along with the purinergic receptor P2Y12, are expressed in the cholangiocyte cilia [97]. P2Y12 can be activated by biliary nucleotides (ATP and ADP) present in the bile [105]. Fluid flow-induced release of ATP activates P2Y12, which cause a rise in intracellular Ca2+ levels, inhibition of AC and reduction in intracellular cAMP levels [97].

Numerous studies have demonstrated cholangiocytes display morphological and functional heterogeneity of cholangiocytes [88,90]. Using real-time PCR analysis, quantitative differences in AC isoform gene expression between small and large cholangiocytes have been found. In small cholangiocytes the Ca2 +-insensitive isoforms AC4 and AC7 are higher expressed, whereas in large cholangiocytes, the Ca2 +-inhibited isoforms AC5, AC6 and AC9, the Ca2+/calmodulin-stimulated AC8 and the soluble AC are higher expressed [103]. Secretin stimulation of secretion varies with the cholangiocyte size and distribution along the bile ducts. The small cholangiocytes that line the small bile ducts do not respond to secretin [88,106]. The large cholangiocytes that line the large bile ducts express the secretin receptor, CFTR, and AE2 secretory machinery and respond to secretin with increased secretion [88,106]. Studies have indicated that small cholangiocyte signaling largely involves Ca2+-dependent mechanisms, but cAMP-dependent signaling predominates in large cholangiocytes [107,108]. Ca2+-insensitive AC isoforms (AC4, AC7) were expressed in higher levels in small bile ducts [103]. However, the expression levels of Ca2+-inhibited isoforms (AC5, AC6, AC9), the Ca2+/calmodulin stimulated AC8 and the soluble AC were elevated in large bile ducts [103]. Silencing of AC8 inhibited bile secretion and cAMP production stimulated by secretin and acetylcholine [103]. Spirli and colleagues also demonstrated that polycystin-2 plays an important role in store operated Ca2+ entry [109]. The activation of store operated Ca2+ entry inhibits the STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule 1)-dependent activation of AC6 by the depletion of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum [109]. Together, these studies indicate that several AC isoforms play a key role in the modulation of cholangiocyte secretory activity.

The role of AC in the regulation of biliary proliferation was evaluated through the use of forskolin [110]. Chronic administration of forskolin to rats stimulated an increase in biliary mass, which occurred through activation of the PKA/Src/MEK/ERK1/2 pathway [110]. Another study has shown that stimulation of AC with agonists for β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors and forskolin prevented liver damage induced by vagotomy [111]. In a recent study, GABA was shown to play a key role in the amplification of Ca2+-dependent signaling in small cholangiocyte following the damage of large bile ducts [107]. In small cholangiocytes, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) stimulated a de novo increase in the secretory machinery (secretin receptor, CFTR, AE2), as well as the expression of the Ca2+-activated AC8 [107]. In a recent study, the authors confirmed that GABA induced the differentiation of small into large cholangiocytes, which was dependent upon the activation of AC8 [108]. These findings indicate that ACs play a key role in the regulation of secretory, proliferative and differentiation responses of small cholangiocytes when large ones are damaged. Further studies are needed to determine the contribution and roles of the other AC isoforms expressed by cholangiocytes.

Among the expression of several AC isoforms, certain ACs are functionally coupled to specific agonists. The Ca2+-stimulated isoform AC8 is responsible for cAMP generation and ductal secretion induced by secretin and acetylcholine from large cholangiocytes. As previously reported, the effect of cholinergic responses on cAMP generation in cholangiocytes is Ca2+-dependent and functions to synergize the response to secretin in promoting Cl−/ exchange [112]. Recently, both in vivo and in vitro studies show that GABA induces the differentiation of small into large cholangiocytes by the activation of Ca2+/CaMKI-dependent AC8. GABA damages large, but not small cholangiocytes that differentiate into large cholangiocytes. The authors suggest that the differentiation of small into large cholangiocytes may be important in the replenishment of the biliary epithelium during damage of large, senescent cholangiocytes [108].

AC9 is responsible for bile secretion induced by the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol. Because intracellular levels of acts as a cellular metabolic sensor (CO2/ ratio) and are necessary for the liver cell secretory properties, thought to be a consequence of transport by Cl−/ exchange or CFTR [96,113], soluble AC10, which is activated by , is required for cholangiocyte secretion induced by metabolic changes.

Induction of cholestatic injuries by treatment with lipopolysaccharide or α-naphthylisothiocyanate in rats increased the expression of AC4 and AC7 in both small and large cholangiocytes, as well as soluble AC in small cholangiocytes, but decreased the expression of AC5, AC6, AC8 and AC9 in both small and large cholangiocytes [103]. The increase in the expression of Ca2+-insensitive PKC-regulated ACs (AC4 and AC7) in liver damage is consistent with their participation in cell proliferation and the repair of liver, while the increase in the expression of soluble AC is likely due to a compensatory mechanism triggered by the metabolic disturbance as a consequence of a decrease in bile secretion.

4.2.2. Role of AC in hepatocytes

Strazzabosco and colleagues were able to identify the pattern of AC isoforms expression not only in cholangioytes, but also hepatocytes [103]. They found that AC isoforms are differently expressed in both cell subpopulations. In hepatocytes, all but AC2 and AC8 isoforms are expressed [103]. Several studies have shown that cAMP pathway protects hepatocytes from bile acid- and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α-)-induced apoptosis in cultured rat hepatocytes and a mouse model of TNF-α-induced liver injury, respectively [114,115]. Finally, taurocholate, one of the most predominant bile acids in mammals, has been show to stimulate hepatocyte polarization through AC-dependent mechanism because the treatment with two different AC inhibitors, 2′, 5′-dideoxyadenosine and MDL-12330A, completely blocked taurocholate-stimulated canalicular network formation in primary rat hepatocytes [116].

4.3. Physiological roles of ACs in other digestive organs

4.3.1. Salivary glands

In parotid gland, AC8 plays a major role in coupling the increase in Ca2+ from capacitive Ca2+ entry to cAMP synthesis. In isolated parotid acini, the cholinergic agonist carbachol and the microsomal Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin enhanced stimulated cAMP formation. The deletion of AC8 not only prevented the enhancement of these agents, but also decreased the effect of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol on cAMP formation [117,118]. Recently, Orai1, the pore component of SOC channels, has been involved in the interplay between Ca2+ and cAMP signaling [119]. In HEK293 cells, using high-resolution biosensors targeted to the AC8 and Orai1 microdomains, a coordinated subcellular change in both Ca2+ and cAMP signaling has been shown when AC8–Orai1 interact.

Unlike AC8, AC5/AC6, which is directly activated by Ca2+, is likely to be involved in the inhibition of cAMP synthesis [117]. The presence of AC5/AC6 may provide a negative feedback mechanism by which stimulated cAMP levels are modulated in parotid acini. In mouse parotid membranes, calmodulin mediates the activation of AC by Ca2+ and that Ca2+, at concentrations that stimulate and inhibit parotid amylase secretion, can respectively activate and inhibit AC activity [120]. Recently, isoproterenol-stimulated parotid amylase secretion has been shown to occur by the formation of an AC6/PKA/A-kinase anchoring protein 5 (AKAP5) complex because AKAP5, which is essential for targeting type II PKA to specific cellular domains, co-immunoprecipitates with AC6, but not AC8 [121]. On the other hand, endogenous NO inhibits AC5/6, and thereby, reduces the cAMP accumulation in isolated mouse parotid acini [122].

Although AC3 was found in parotid membranes from acini based on immunoblot analysis, AC3 was not involved in thapsigargin-induced inhibition of stimulated cAMP accumulation [117].

In the blowfly salivary gland, a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent AC1 has been characterized by both pharmacological and molecular approaches, as well as by reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis. It is likely that AC1 acts to coordinate IP3/Ca2+ and cAMP/PKA pathways, which is necessary for secretion [123].

4.3.2. Stomach

The activation of AC stimulates gastric acid secretion in parietal cells. Several studies using different species showed specie-selective effects of stimulants and inhibitors on gastric mucosal AC activity [124–128]. For example, in rat gastric corpus mucosal membrane, inhibitors of gastric acid secretion such as prostaglandin E1, secretin and catecholamines, all stimulate AC activity [126]. Human gastric mucosal AC has been shown to be sensitive to histamine and catecholamines [129]. Histamine, which is released from paracrine cells near the oxyntic cells, binds to the H2-receptors on the oxyntic cell plasma membrane, activating AC/cAMP pathway, and thereby, stimulating gastric acid secretion [130]. Forskolin, which activates all AC isoforms except AC9, stimulates gastric acid secretion in isolated rat parietal cells and in vivo [131,132].

4.3.3. Intestine

The activation of AC induces changes in intestinal fluid absorption. Forskolin increased the active transport of D-glucose and reduced fluid transport in rat jejunum [133]. In marine teleost fish intestine, soluble AC regulates the Na+–K+–Cl− cotransporter (NKCC) activity in response to luminal , and thereby, NaCl absorption [134]. A combination of an inhibitor of soluble AC, 4-catechol estrogen, and a specific inhibitor of NKCC, bumetanide, abolished a induced-luminal positive short-circuit current in intestine mounted in Ussing chamber. The response of was also reduced by an inhibitor of V-H+-ATPase, bafilomycin, and by an inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase, etoxolamide [134]. In the marine fish Sparus aurata intestine, both water absorption and secretion induced by transmembrane ACs are locally and reciprocally regulated by the effect of soluble ACs [135]. A combination of forskolin and the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX, as well as the soluble AC inhibitor KH7 were used to study the participation of transmembrane ACs and soluble AC, respectively. These findings show that soluble AC acts as a chemical metabolic sensor (CO2/ ratio) to locally integrate the cellular response of chemical metabolic sensing and endocrine control [135].

5. Conclusion

In this review, we highlight the differences in expression of AC isoforms in the digestive system (Table 2). AC isoforms are differentially expressed in mouse pancreatic acini and ducts: AC3, AC4, AC6, AC9 mRNAs were expressed in isolated pancreatic acini and sealed duct fragments, whereas AC7 mRNAs was only expressed in duct fragments [36]. Soluble AC was found in isolated pancreatic acini [25]. Whereas AC6 plays a secretory role in both pancreatic acini and ducts, soluble AC plays a protective role in acute pancreatitis [25,36].

Table 2.

Tissue distribution of AC isoforms in digestive tract organs.

| TISSUE | AC1 | AC2 | AC3 | AC4 | AC5 | AC6 | AC7 | AC8 | AC9 | AC10 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver: | |||||||||||

| – Hepatocytes | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | [103, 138] | ||

| – Cholangiocytes | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | [103] | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Pancreas: | |||||||||||

| – Acini | + | + | +(†) | +(†) | [25, 36] | ||||||

| – Duct fragment | + | + | + | + | + | [25] | |||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Parotid Gland | +(†) | +(†) | +(†) | + | [117, 118] | ||||||

Distribution of AC isoforms in different digestive tract organs. ACs are differently expressed in liver, exocrine pancreas and parotid gland. (+): AC isoform is expressed. (†): AC isoforms documented at the protein level by immunoblotting.

: AC isoform is expressed.

: AC isoforms documented at the protein level by immunoblotting.

In cholangiocytes, AC4, AC5, AC6, AC7, AC8 and AC9 mRNAs are expressed, as well as the soluble AC, AC10. The Ca2+-insensitive ACs (AC4 and AC7) are highly expressed in small cholangiocytes, whereas the Ca2+-stimulated ACs (AC5, AC6, AC8, and AC9) and the -activated soluble AC are highly expressed in large cholangiocytes [136]. AC8 is responsible for bile secretion and cAMP production stimulated by secretin and acetylcholine, whereas AC9 is responsible for bile secretion induced by the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol. Soluble AC is required for cholangiocyte secretion induced by metabolic changes [103]. These findings are consistent with the fact that large cholangiocytes play an important role in the formation of bile secretion and are both Ca2+- and -regulated [106,112,137]. Expression of Ca2+-insensitive PKC-regulated ACs in small cholangiocytes is consistent with their ability to proliferate and participate in the repair of liver damage. In hepatocytes, all the AC isoforms are expressed, except AC2 and AC8 [103,138]. The physiological relevance of every AC isoform in hepatocytes is still unknown.

In parotid gland, AC5/AC6 is likely to be involved in the inhibition of cAMP synthesis [117]. On the other hands, AC8 plays a major role in coupling the increase in Ca2+ from capacitive Ca2+ entry to cAMP synthesis: the absence of AC8 not only prevented the enhancement of cholinergic agonist carbachol and the microsomal Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin on cAMP formation, but also decreased the effect of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol on cAMP [117,118].

In stomach, the activation of AC stimulates gastric acid secretion from parietal cells. However, the expression of AC isoforms and their physiological relevance have not been fully studied. In intestine, AC increases the active transport of D-glucose and reduces fluid transport in jejunum. Soluble AC is likely to play a role as a chemical metabolic sensor and regulates intestinal fluid absorption [134,135].

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Dr. Watson for their valuable insights in the role of AC in salivary glands. FSG is supported by NIH R01 (DK54021) and a VA Career Development and Merit Awards.

Abbreviations

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator

- CREBs

cAMP response element binding proteins

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- Epac

Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP

- GDP

guanosine diphosphate

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GPCR

G protein coupled receptors

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- NKCC

Na+–K+–Cl− cotransporter

- NO

nitric oxide

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

References

- 1.Hurley JH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7599–7602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor SS, Zhang P, Steichen JM, Keshwani MM, Kornev AP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shabb JB. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2381–2411. doi: 10.1021/cr000236l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Sullivan AJ, Jamieson JD. Biochem J. 1992;287(Pt 2):403–406. doi: 10.1042/bj2870403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quissell DO, Barzen KA, Deisher LM. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:443–448. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040032601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada K, Inoue H, Kida S, Masushige S, Nishiyama T, Mishima K, Saito I. Pathobiology. 2006;73:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000093086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabbatini ME, Chen X, Ernst SA, Williams JA. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23884–23894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800754200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perides G, Sharma A, Gopal A, Tao X, Dwyer K, Ligon B, Steer ML. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G713–G721. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00519.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bos JL. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaudhuri A, Husain SZ, Kolodecik TR, Grant WM, Gorelick FS. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1403–G1410. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00478.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimomura H, Imai A, Nashida T. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;431:124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck J, Sinclair ML, Schapal L, Cann MJ, Levin LR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:79–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadana R, Dessauer CWT. Neurosignals. 2009;17:5–22. doi: 10.1159/000166277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beazely MA, Watts VJ. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;535:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willoughby D, Cooper DM. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:965–1010. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Premont RT, Matsuoka I, Mattei MG, Pouille Y, Defer N, Hanoune J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13900–13907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper DM, Mons N, Karpen JW. Nature. 1995;374:421–424. doi: 10.1038/374421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krupinski J, Coussen F, Bakalyar HA, Tang WJ, Feinstein PG, Orth K, Slaughter C, Reed RR, Gilman AG. Science. 1989;244:1558–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.2472670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feinstein PG, Schrader KA, Bakalyar HA, Tang WJ, Krupinski J, Gilman AG, Reed RR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10173–10177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang G, Liu Y, Ruoho AE, Hurley JH. Nature. 1997;386:247–253. doi: 10.1038/386247a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun T, Dods RF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1097–1101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun T, Frank H, Dods R, Sepsenwol S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;481:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(77)90155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed BY, Gitomer WL, Heller HJ, Hsu MC, Lemke M, Padalino P, Pak CY. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1476–1485. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinclair ML, Wang XY, Mattia M, Conti M, Buck J, Wolgemuth DJ, Levin LR. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;56:6–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200005)56:1<6::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolodecik TR, Shugrue CA, Thrower EC, Levin LR, Buck J, Gorelick FS. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaiswal BS, Conti M. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31698–31708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011698200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wuttke MS, Buck J, Levin LR. JOP. 2001;2:154–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrell J, Ramos L, Tresguerres M, Kamenetsky M, Levin LR, Buck J. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zippin JH, Chen Y, Nahirney P, Kamenetsky M, Wuttke MS, Fischman DA, Levin LR, Buck J. FASEB J. 2003;17:82–84. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0598fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierre S, Eschenhagen T, Geisslinger G, Scholich K. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:321–335. doi: 10.1038/nrd2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Cann MJ, Litvin TN, Iourgenko V, Sinclair ML, Levin LR, Buck J. Science. 2000;289:625–628. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaiswal BS, Conti M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10676–10681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831008100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Litvin TN, Kamenetsky M, Zarifyan A, Buck J, Levin LR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15922–15926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nomura M, Beltran C, Darszon A, Vacquier VD. Gene. 2005;353:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zippin JH, Chen Y, Straub SG, Hess KC, Diaz A, Lee D, Tso P, Holz GG, Sharp GW, Levin LR, Buck J. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:33283–33291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabbatini ME, D’Alecy L, Lentz SI, Tang T, Williams JA. J Physiol. 2013;591:3693–3707. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.249698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willoughby D, Halls ML, Everett KL, Ciruela A, Skroblin P, Klussmann E, Cooper DM. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5850–5859. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Chen L, Kass RS, Dessauer CW. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29815–29824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayati A, Levoin N, Paris H, N’Diaye M, Courtois A, Uriac P, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Fardel O, Le Ferrec E. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4041–4052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.319970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zippin JH, Farrell J, Huron D, Kamenetsky M, Hess KC, Fischman DA, Levin LR, Buck J. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:527–534. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stessin AM, Zippin JH, Kamenetsky M, Hess KC, Buck J, Levin LR. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17253–17258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603500200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Branham MT, Bustos MA, De Blas GA, Rehmann H, Zarelli VE, Trevino CL, Darszon A, Mayorga LS, Tomes CN. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24825–24839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.015362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh P, Asada I, Owlia A, Collins TJ, Thompson JC. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:G217–G223. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.2.G217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsushita K, Okabayashi Y, Hasegawa H, Koide M, Kido Y, Okutani T, Sugimoto Y, Kasuga M. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1146–1152. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90286-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stryjek-Kaminska D, Piiper A, Zeuzem S. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G676–G682. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.5.G676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marino CR, Leach SD, Schaefer JF, Miller LJ, Gorelick FS. FEBS Lett. 1993;316:48–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81734-h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long BW, Gardner JD. Gastroenterology. 1977;73:1008–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Argent BE, Gray MA, Steward MC, Case RM. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Johnson LR, editor. Elsevier inc; 2012. pp. 1399–1423. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee MG, Wigley WC, Zeng W, Noel LE, Marino CR, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3414–3421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dehaye JP, Gillard M, Poloczek P, Stievenart M, Winand J, Christophe J. J Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphor Res. 1985;10:269–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimura T, Imamura K, Eckhardt L, Schulz I. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:G698–G708. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.250.5.G698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heisler S. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983;61:1168–1176. doi: 10.1139/y83-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gardner JD, Korman LY, Walker MD, Sutliff VE. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:G547–G551. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.6.G547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willems PH, Tilly RH, de Pont JJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;928:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matozaki T, Sakamoto C, Nagao M, Nishizaki H, Baba S. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:E652–E659. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1988.255.5.E652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burnham DB, McChesney DJ, Thurston KC, Williams JA. J Physiol. 1984;349:475–482. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burnham DB, Sung CK, Munowitz P, Williams JA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;969:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(88)90085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Akiyama T, Hirohata Y, Okabayashi Y, Imoto I, Otsuki M. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G1202–G1208. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.5.G1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willems PH, van Nooij IG, Haenen HE, de Pont JJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;930:230–236. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang T, Gao MH, Lai NC, Firth AL, Takahashi T, Guo T, Yuan JX, Roth DM, Hammond HK. Circulation. 2008;117:61–69. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chiono M, Mahey R, Tate G, Cooper DM. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1149–1155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lefkimmiatis K, Srikanthan M, Maiellaro I, Moyer MP, Curci S, Hofer AM. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:433–442. doi: 10.1038/ncb1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fagan KA, Smith KE, Cooper DM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26530–26537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohnishi H, Mine T, Kojima I. Biochem J. 1994;304(Pt 2):531–536. doi: 10.1042/bj3040531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Viguerie N, Tahiri-Jouti N, Esteve JP, Clerc P, Logsdon C, Svoboda M, Susini C, Vaysse N, Ribet A. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:G113–G120. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.255.1.G113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu Z, Kolodecik TR, Karne S, Nyce M, Gorelick F. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G822–G828. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00213.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chaudhuri A, Kolodecik TR, Gorelick FS. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G235–G243. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00334.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun XC, Zhai CB, Cui M, Chen Y, Levin LR, Buck J, Bonanno JA. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C1114–C1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00400.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y, Lam CS, Wu F, Wang W, Duan Y, Huang P. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1145–C1151. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00627.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Acin-Perez R, Salazar E, Kamenetsky M, Buck J, Levin LR, Manfredi G. Cell Metab. 2009;9:265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li S, Allen KT, Bonanno JA. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C368–C374. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00314.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jiang LI, Collins J, Davis R, Fraser ID, Sternweis PC. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23429–23439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803281200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen Z, Singer WD, Wells CD, Sprang SR, Sternweis PC. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9912–9919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sabbatini ME, Bi Y, Ji B, Ernst SA, Williams JA. CCK activates RhoA and Rac1 differentially through Galpha13 and Galphaq in mouse pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C592–601. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00448.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cooper DM. Biochem J. 2003;375:517–529. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Groblewski GE, Yoshida M, Bragado MJ, Ernst SA, Leykam J, Williams JA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22738–22744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gurda GT, Guo L, Lee SH, Molkentin JD, Williams JA. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:198–206. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Groblewski GE, Wagner AC, Williams JA. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15111–15117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Husain SZ, Grant WM, Gorelick FS, Nathanson MH, Shah AU. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1594–G1599. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00500.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cumbay MG, Watts VJ. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1247–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Duan RD, Guo YJ, Williams JA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:368–373. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sutherland EW, Robison GA. Pharmacol Rev. 1966;18:145–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sutherland EW, Rall TW. Acta Endocrinol Suppl. 1960;34(Suppl. 50):171–174. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.xxxivs171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sutherland EW, Oye I, Butcher RW. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1965;21:623–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sutherland EW, Rall TW, Menon T. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:1220–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alpini G, Lenzi R, Sarkozi L, Tavoloni N. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:569–578. doi: 10.1172/JCI113355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kanno N, LeSage G, Glaser S, Alpini G. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G612–G625. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Alpini G, Roberts S, Kuntz SM, Ueno Y, Gubba S, Podila PV, LeSage G, LaRusso NF. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1636–1643. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Glaser SS, Gaudio E, Rao A, Pierce LM, Onori P, Franchitto A, Francis HL, Dostal DE, Venter JK, DeMorrow S, Mancinelli R, Carpino G, Alvaro D, Kopriva SE, Savage JM, Alpini GD. Lab Invest. 2009;89:456–469. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kanno N, LeSage G, Glaser S, Alvaro D, Alpini G. Hepatology. 2000;31:555–561. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Strazzabosco M, Mennone A, Boyer JL. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1503–1512. doi: 10.1172/JCI115160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Strazzabosco M, Fabris L, Spirli C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S90–S102. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155549.29643.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Munshi MK, Priester S, Gaudio E, Yang F, Alpini G, Mancinelli R, Wise C, Meng F, Franchitto A, Onori P, Glaser SS. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Marzioni M, Fava G, Benedetti A. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3471–3480. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i22.3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Alpini G, Ulrich CD, II, Phillips JO, Pham LD, Miller LJ, LaRusso NF. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:G922–G928. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.5.G922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Banales JM, Prieto J, Medina JF. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3496–3511. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i22.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Masyuk AI, Gradilone SA, Banales JM, Huang BQ, Masyuk TV, Lee SO, Splinter PL, Stroope AJ, Larusso NF. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G725–G734. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fiorotto R, Spirli C, Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Okolicsanyi L, Strazzabosco M. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1603–1613. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Minagawa N, Nagata J, Shibao K, Masyuk AI, Gomes DA, Rodrigues MA, Lesage G, Akiba Y, Kaunitz JD, Ehrlich BE, Larusso NF, Nathanson MH. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1592–1602. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Uriarte I, Banales JM, Saez E, Arenas F, Oude Elferink RP, Prieto J, Medina JF. Hepatology. 2010;51:891–902. doi: 10.1002/hep.23403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tietz PS, Marinelli RA, Chen XM, Huang B, Cohn J, Kole J, McNiven MA, Alper S, LaRusso NF. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20413–20419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Spirli C, Fabris L, Duner E, Fiorotto R, Ballardini G, Roskams T, Larusso NF, Sonzogni A, Okolicsanyi L, Strazzabosco M. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:737–753. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Strazzabosco M, Fiorotto R, Melero S, Glaser S, Francis H, Spirli C, Alpini G. Hepatology. 2009;50:244–252. doi: 10.1002/hep.22926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, LaRusso NF. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2007–2012. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Woo K, Dutta AK, Patel V, Kresge C, Feranchak AP. J Physiol. 2008;586:2779–2798. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Alpini G, Glaser S, Robertson W, Rodgers RE, Phinizy JL, Lasater J, LeSage GD. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G1064–G1074. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.5.G1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mancinelli R, Franchitto A, Gaudio E, Onori P, Glaser S, Francis H, Venter J, Demorrow S, Carpino G, Kopriva S, White M, Fava G, Alvaro D, Alpini G. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1790–1800. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mancinelli R, Franchitto A, Glaser S, Meng F, Onori P, Demorrow S, Francis H, Venter J, Carpino G, Baker K, Han Y, Ueno Y, Gaudio E, Alpini G. Hepatology. 2013;58:251–263. doi: 10.1002/hep.26308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Spirli C, Locatelli L, Fiorotto R, Morell CM, Fabris L, Pozzan T, Strazzabosco M. Hepatology. 2012;55:856–868. doi: 10.1002/hep.24723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 110.Francis H, Glaser S, Ueno Y, Lesage G, Marucci L, Benedetti A, Taffetani S, Marzioni M, Alvaro D, Venter J, Reichenbach R, Fava G, Phinizy JL, Alpini G. J Hepatol. 2004;41:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Glaser S, Alvaro D, Francis H, Ueno Y, Marucci L, Benedetti A, De Morrow S, Marzioni M, Mancino MG, Phinizy JL, Reichenbach R, Fava G, Summers R, Venter J, Alpini G. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G813–G826. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00306.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Alvaro D, Alpini G, Jezequel AM, Bassotti C, Francia C, Fraioli F, Romeo R, Marucci L, Le Sage G, Glaser SS, Benedetti A. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1349–1362. doi: 10.1172/JCI119655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Choi JY, Lee MG, Ko S, Muallem S. JOP. 2001;2:243–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Webster CR, Anwer MS. Hepatology. 1998;27:1324–1331. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Takano M, Arai T, Mokuno Y, Nishimura H, Nimura Y, Yoshikai Y. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3:109–117. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0109:dcampm>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fu D, Wakabayashi Y, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Arias IM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1403–1408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018376108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Watson EL, Jacobson KL, Singh JC, Idzerda R, Ott SM, DiJulio DH, Wong ST, Storm DR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14691–14699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Watson EL, Wu Z, Jacobson KL, Storm DR, Singh JC, Ott SM. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C557–C565. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.3.C557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Willoughby D, Everett KL, Halls ML, Pacheco J, Skroblin P, Vaca L, Klussmann E, Cooper DM. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra29. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Piascik MT, Babich M, Jacobson KL, Watson EL. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:C642–C645. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.250.4.C642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wu CY, DiJulio DH, Jacobson KL, McKnight GS, Watson EL. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C1151–C1158. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00382.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Watson EL, Singh JC, Jacobson KL, Ott SM. Cell Signal. 2001;13:755–763. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Heindorff K, Blenau W, Walz B, Baumann O. Cell Calcium. 2012;52:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Thompson WJ, Rosenfeld GC, Jacobson ED. Fed Proc. 1977;36:1938–1941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Thompson WJ, Jacobson ED. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1977;154:377–381. doi: 10.3181/00379727-154-37675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Thompson WJ, Chang LK, Rosenfeld GC, Jacobson ED. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Thompson WJ, Chang LK, Jacobson ED. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:244–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Anttila P, Lucke C, Westermann E. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1976;296:31–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00498837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Simon B, Kather H. Digestion. 1977;16:175–179. doi: 10.1159/000198069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wollin A. Med Clin Exp. 1987;10:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Choquet A, Magous R, Galleyrand JC, Bali JP. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1988;182:335–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wilson GA, Main IH. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;123:371–377. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90711-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Reymann A, Braun W, Bergheim M, Hissnauer K. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1985;328:317–323. doi: 10.1007/BF00515560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tresguerres M, Levin LR, Buck J, Grosell M. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R62–R71. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00761.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Carvalho ES, Gregorio SF, Power DM, Canario AV, Fuentes J. J Comp Physiol B Biochem Syst Environ Physiol. 2012;182:1069–1080. doi: 10.1007/s00360-012-0685-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.S M, Strazzabosco M, Spirli C, Fiorotto R, Glaser S, Francis HL, Alpini G. Hepatology. 2003;38:687A. doi: 10.1002/hep.22926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Splinter PL, Huang BQ, Stroope AJ, LaRusso NF. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:911–920. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Premont RT, Chen J, Ma HW, Ponnapalli M, Iyengar R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:9809–9813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Defer N, Best-Belpomme M, Hanoune J. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F400–F416. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.3.F400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Nelson EJ, Hellevuo K, Yoshimura M, Tabakoff B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4552–4560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chen Y, Harry A, Li J, Smit MJ, Bai X, Magnusson R, Pieroni JP, Weng G, Iyengar R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14100–14104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]