Abstract

A small set of triazole bisphosphonates has been prepared and tested for the ability to inhibit geranylgeranyl transferase II (GGTase II). The compounds were prepared through use of click chemistry to assemble a central triazole that links a polar head group to a hydrophobic tail. The resulting compounds were tested for their ability to inhibit GGTase II in an in vitro enzyme assay and also were tested for cytotoxic activity in an MTT assay with the human myeloma RPMI-8226 cell line. The most potent enzyme inhibitor was the triazole with a geranylgeranyl tail, which suggests that inhibitors that can access the enzyme region that holds the isoprenoid tail will display greater activity.

Keywords: GGTase II, Rab GGTase, apoptosis, anti-proliferative, bioassay

Protein prenylation is a post-translational modification which involves attachment of hydrophobic isoprenoid chains through a reaction that is mediated by the enzymes farnesyltransferase (FTase), geranylgeranyltransferase I (GGTase I), or geranylgeranyltransferase II (GGTase II).1 The latter enzyme is also known as Rab GGTase because it mediates modification of the Rab family of small GTPases.2 Rab proteins play critical roles in all aspects of intracellular membrane trafficking.3 Studies involving mutated versions of Rabs or knock-out mice have demonstrated defects in protein secretion,4 which may make the Rab proteins particularly attractive therapeutic targets in diseases characterized by an overabundance of secreted proteins such as multiple myeloma. Proper function of Rab proteins depends upon correct membrane localization which is achieved through geranylgeranylation. Mutant forms of Rabs that are unable to be geranylgeranylated are improperly localized and essentially nonfunctional.5 We already have demonstrated that agents which disrupt Rab geranylgeranylation result in the inhibition of monoclonal protein trafficking in myeloma cells.6 This represents an intriguing therapeutic strategy by which to induce cellular stress and apoptosis in cells heavily engaged in protein secretion.

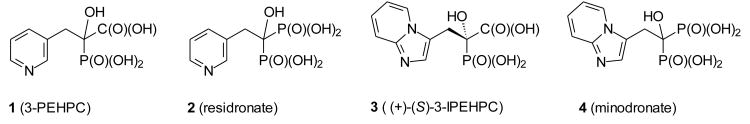

At least two lines of attack may achieve diminished cellular levels of Rab geranylgeranylation. The less direct approach would be to deplete cells of the isoprenoid substrate geranylgeranyl diphosphate. This might be achieved by inhibition of any of the individual steps in the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway that lead to geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGDP), from inhibition of HMGCoA reductase by a statin7 (the first committed step in isoprenoid biosynthesis8) to inhibition of GGPP synthase9 (the final enzyme in the assembly of this C20 isoprenoid10). This strategy is less specific as it affects other cellular processes requiring the isoprenoid intermediates, including other prenyltransferases. The more direct strategy involves inhibition of GGTase II itself. While inhibitors of GGTase II are rare,11 a few have been reported. The carboxy phosphonate 1, an analogue of the bisphosphonate residronate (2) known as 3-PEHPC, is one of the more readily accessible inhibitors.12 This compound displays good selectivity for GGTase II although millimolar concentrations are required to observe cellular effects and the IC50 first reported for the recombinant enzyme was ∼600 μM.12 More recently (+)-3-IPEHPC (3), a carboxy phosphonate analogue of minodronate (4), has been shown to be more potent than 3-PEHPC, to be a mixed-type inhibitor with respect to GGPP, and to be an uncompetitive inhibitor with respect to Rab.13 Efforts that have involved actual screening of a compound library that contained a significant number of natural products14 and a virtual high-throughput screening of a tetrahydrobenzodiazepine core15 also have led to compounds with activity as inhibitors of GGTase II. Our own approach is based on a longstanding interest in the design of terpenoid analogues as inhibitors of the enzymes of isoprenoid biosynthesis.16 In this report, we describe efforts to assemble a small set of potential inhibitors of GGTase II based on a triazole template with varied hydrophobic tails that might engage an isoprenoid binding region of the protein, as well as the results of bioassays on these new compounds.

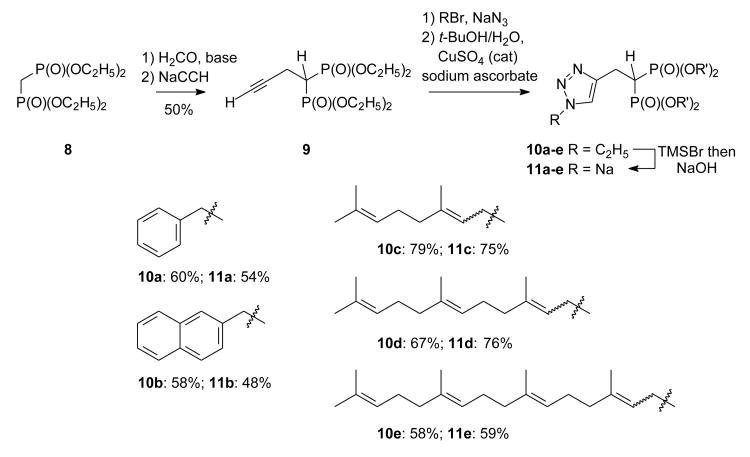

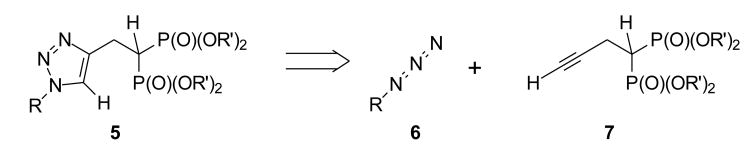

In compounds such as 3-PEHPC and (S)-3-IPEHPC, the polar head group appears to represent the diphosphate moiety of geranylgeranyl diphosphate while the nitrogen atom may complex to the zinc ion known to be near the active site of GGTase II. Our synthetic plan was directed at compounds of the general structure 5 (Figure 2), which might maintain features needed to engage these sites within the enzyme but also carry a hydrophobic tail that would mimic the isoprenoid portion of GGPP. Assembly of such structures is readily approached through cycloaddition of an azide and an acetylene, a process commonly referred to as click chemistry.17 The most convenient preparation of the desired compounds would require an acetylene bearing the polar head group and a set of azides with alkyl groups of different size and shape (Figure 2). To simplify determination of the impact of various alkyl chains, and avoid issues of absolute stereochemistry at this time, a bisphosphonate head group was employed as the diphosphate mimic.

Figure 2.

Retrosynthesis of a family of triazole bisphosphonates.

In a synthetic sense, this effort began with preparation of the known acetylenic bisphosphonate 9 from commercial tetraethyl methylene bisphosphonate (8), formaldehyde, and acetylene according to the two-step sequence described by Roschenthaler.18 The first cycloadduct then was obtained from reaction of acetylene 9 with benzyl azide, generated from benzyl bromide and sodium azide, and gave the known triazole 10a18 in good yield. Standard hydrolysis under McKenna conditions19 gave the new bisphosphonic acid 11a in modest yield. A parallel series of reactions with naphthyl bromide was employed to prepare the naphthyl analogue 10b, and cleavage of the ester groups proceeded smoothly under standard conditions to afford compound 11b.

Given the encouraging results obtained from the reactions of benzyl and naphthyl azide, one might assume that isoprenoid halides can be converted to triazoles just as readily, but allylic systems are more complicated than the benzylic ones. Allylic azides are known to undergo a facile [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement.20 More recent studies on prenyl azide show that the primary azide is both more reactive in the [3 + 2] cycloaddition and favored in the equilibrium between the primary and tertiary azides.21 Unfortunately this equilibrium can result in partial isomerization of a trans olefin to a cis olefin21 which can complicate preparation of triazoles from higher isoprenoid azides.22

To pursue preparation of the first isoprenoid triazole in this series, geranyl bromide was obtained from geraniol through reaction with PBr3, converted to the azide, and the resulting azide was allowed to react with acetylene 9 under standard conditions to obtain the triazole 10c. The spectral data supported formation of the desired triazole system, but the 13C NMR spectrum of the product suggested that a mixture of isomers was obtained. To confirm that this mixture was the result of olefin isomerization at the stage of the intermediate azide, and not reflective of the regiochemistry of the cycloaddition, the isomeric neryl bromide was converted to the azide and carried through the same reaction sequence. The resulting product was identical to that obtained from the geranyl series, which confirms formation of E- and Z-olefin isomers through this reaction sequence. Whether geranyl bromide or neryl bromide was employed as the starting material, the isomer ratio was approximately 2:1 in favor of the E-isomer, as judged by integration of the 1H NMR resonances for the methyl or vinyl hydrogens of the first isoprenoid unit.

The corresponding farnesyl triazole 10d was prepared from commercial farnesol through a parallel series of reactions involving sequential formation of the bromide, the azide, and a final cycloaddition. Once again, the resulting triazole was found to be a mixture of olefin isomers. Preparation of the geranylgeranyl analog 10e required synthesis of geranylgeraniol from reaction of farnesyl acetone with triethyl phosphonoacetate, and reduction of the resulting ester with LiAlH4.23 This strategy is known to favor formation of the 2E isomer by approximately 10:1, which is not problematic for this application given the expected isomerization after preparation of the azide. Therefore, geranylgeraniol prepared this way was converted to the bromide, the azide, and finally to the triazole 10e under standard conditions. In all three of these isoprenoid cases (compounds 10c-10e), the high polarity of the bisphosphonate head group made separation of the olefin isomers very difficult. Therefore, the mixtures were carried on to the corresponding phosphonic acid salts 11c-11e through straightforward cleavage of the ester groups, and then used directly for screening purposes.

The five new triazole bisphosphonic acids were tested for their ability to inhibit GGTase II using radiolabeled GGPP, recombinant enzyme, Rab substrate, and REP.24 As shown in Table 1, the length of the alkyl chain significantly affected inhibitory activity against GGTase II. The most active compound was the triazole bisphosphonate 11e, which bears a geranylgeranyl chain. The geranyl length compound 11c displayed no activity as a GGTase II inhibitor, while the farnesyl length 11d displayed modest activity. All five compounds also were tested for their ability to induce cytotoxicity in the human myeloma RPMI-8226 cell line following a 48 hr incubation.25 Interestingly, there was not a uniform correlation between the observed cytotoxicity and the GGTase II inhibitory activity. The napthyl derivative 11b, was the most potent in the MTT assay. The mechanism of action for this compound's cytotoxic effect is unknown at this time. Cellular assays demonstrated that this compound does not affect protein farnesylation or geranylgeranylation (data not shown).

Table 1.

Biological activity of triazoles 11a-e.

| Compound | GGTase II IC50 | MTT IC50 |

|---|---|---|

| 11a (3-19) | 2 mM | > 1 mM |

| 11b (3-24) | > 2 mM | 0.2 mM |

| 11c (2-264) | >2 mM | >1 mM |

| 11d (2-286) | 0.65 mM | 0.9 mM |

| 11e (2-296) | 0.10 mM | 1 mM |

In conclusion, click chemistry has been used to prepare a set of five new triazole bisphosphonic acids, and these compounds have been tested for their ability to inhibit GGTase II and to induce cytotoxicity in human myeloma cells. Of these five compounds, compound 11e clearly is the most potent inhibitor of this enzyme. This suggests that a long, lipophilic tail can enhance the potency of potential GGTase II inhibitors, presumably through interaction with the enzyme site that holds the tail of the natural substrate geranylgeranyl diphosphate. The potency of this new compound is not yet at the level required for clinical utility. However, now that the importance of this hydrophobic group is apparent, it is quite likely that modification of the polar head group and/or hetereocyclic system will afford even more potent inhibitors of the enzyme. Furthermore, given the promising activity observed with these triazoles, synthesis of additional examples where olefin isomerization is precluded through use of a homoallylic azide26 or through replacement of the first prenyl unit with an aromatic analogue27 becomes a priority. Studies along these lines are underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Two carboxy phosphonates that inhibit GGTase II and their parent bisphosphonates.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of the target triazole bisphosphonates.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust (DFW), the Institute for Clinical and Translational Science - Looking into Clinical Connections Faculty Development Program at the University of Iowa (DFW), the PhRMA Foundation (SAH), and the University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Cancer CSET seed grant program (SAH) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supplementary data. Supplementary data associated with this article, including representative experimental procedures, NMR spectra, and bioassay protocols can be found in the online version, at

References and notes

- 1.Schafer WR, Rine JL. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seabra MC, Goldstein JL, Sudhof TC, Brown MS. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz J, Doerks T, Ponting CP, Copley RR, Bork P. Nat Genet. 2000;25:201. doi: 10.1038/76069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuda M. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2801. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes AQ, Ali BR, Ramalho JS, Godfrey RF, Barral DC, Hume AN, Seabra MC. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1882. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holstein SA, Hohl RJ. Leuk Res. 2011;35:551. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holstein SA. In: The isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway and statins. Hrycyna CA, Bergo MO, Tamanoi F, editors. The Enzymes: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiemer AJ, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Anticancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;9:526. doi: 10.2174/187152009788451860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Shull LW, Wiemer AJ, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:4130. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wiemer AJ, Yu JS, Lamb KM, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:390. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chen CK, Hudock MP, Zhang Y, Guo RT, Cao R, No JH, Liang PH, Ko TP, Chang TH, Chang SC, Song Y, Axelson J, Kumar A, Wang AH, Oldfield E J Med Chem. 2008;51:5594. doi: 10.1021/jm800325y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiemer AJ, Wiemer DF, Hohl RJ. Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;90:805. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Oualid F, Cohen LH, van der Marel1 GA, Overhand M. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;13:2385. doi: 10.2174/092986706777935078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Coxon FP, Helfrich MH, Larijani B, Muzylak M, Dunford JE, Marshall D, McKinnon AD, Nesbitt JE, Horton MA, Seabra MC, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Coxon FP, Ebetino FH, Mules EH, Seabra MC, McKenna CE, Rogers MJ. Bone. 2005;37:349. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron RA, Tavare R, Figueiredo AC, Blazewska KM, Kashemirov BA, McKenna CA, Ebetino FH, Taylor A, Rogers MJ, Coxon FP, Seabra MC. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806952200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deraeve C, Guo Z, Bon RS, Blankenfeldt W, DiLucrezia R, Wolf A, Menninger S, Stigter EA, Wetzel S, Choidas A, Alexandrov K, Waldmann H, Goody RS, Wu YW. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7384. doi: 10.1021/ja211305j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bon RS, Guo Z, Stigter EA, Wetzel S, Menninger S, Wolf A, Choidas A, Alexandrov K, Blankenfeldt W, Goody RS, Waldmann H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:4957. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Holstein SA, Cermak DM, Wiemer DF, Lewis K, Hohl RJ. Bioorg Med Chem. 1998;6:687. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kim MK, Kleckley TS, Wiemer AJ, Holstein SA, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. J Org Chem. 2004;69:8186. doi: 10.1021/jo049101w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Maalouf MA, Wiemer AJ, Kuder CH, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:1959. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Wiemer AJ, Yu JS, Shull LW, Barney RJ, Wasko BM, Lamb KM, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:3652. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2004. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kolb HC, Sharpless KB. Drug Discovery Today. 2003:1128. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skarpos H, Osipov SN, Vorob'eva DV, Odinets IL, Lork E, Roschenthaler GV. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:2361. doi: 10.1039/b705510b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKenna CE, Higa MT, Cheung NH, McKenna MC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;18:155. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padwa A, Sa MM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:5087. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman AK, Colasson B, Sharpless KB, Fokin VV. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13444. doi: 10.1021/ja050622q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Praud-Tabaries A, Dombrowsky L, Bottzek O, Briand JF, Blache Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1645. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu JS, Kleckley TS, Wiemer DF. Org Letters. 2005;7:4803. doi: 10.1021/ol0513239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seabra MC, James GL. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;84:251. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-488-7:251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holstein SA, Hohl RJ. Leuk Res. 2001;25:651. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(00)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergman JA, Hahne K, Song J, Hrycyna CA, Gibbs RA. Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:15. doi: 10.1021/ml200106d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barney RJ, Wasko BM, Dudakovic A, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:7212. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.