Abstract

Context

Family satisfaction is an important and commonly used research measure. Yet current measures of family satisfaction are lengthy and may be unnecessarily burdensome – particularly in the setting of serious illness.

Objectives

To use an item bank to develop short-forms of the FAMCARE scale, which measures family satisfaction with care.

Methods

To shorten the existing 20-item FAMCARE measure, item response theory parameters from an item bank were used to select the most informative items. The psychometric properties of the new short-form scales were examined. The item bank was based on data from family members from an ethnically diverse sample of 1983 patients with advanced cancer.

Results

Evidence for the new short-form scales supported essential unidimensionality. Reliability estimates from several methods were relatively high, ranging from 0.84 for the five-item scale to 0.94 for the 10-item scale across different age, gender, education, ethnic and relationship groups.

Conclusion

The FAMCARE-10 and FAMCARE-5 short-form scales evidenced high reliability across sociodemographic subgroups, and are potentially less burdensome and time-consuming scales for monitoring family satisfaction among seriously ill patients.

Keywords: Family satisfaction, item banks, item response theory, short-form FAMCARE

Introduction

Satisfaction with care is a key outcome variable for evaluating quality of care for patients with serious illness [1–3] and is the most commonly measured outcome for caregivers of patients receiving palliative care [4]. Satisfaction with care includes the following components: accessibility, coordination, emotional support, personalization of care and support of decision making [5]. Caregiver satisfaction is posited to improve patient care because satisfied caregivers are better able to handle their challenging role [6, 7]. Satisfaction with care also is associated with improved adjustment post-death [8]. Additionally, family satisfaction with care is highly correlated with patient satisfaction [9], which cannot always be measured adequately in late-stage illness. Data suggest that satisfaction with care may be more important for patient quality of life than symptom relief [10].

Researchers are increasingly concerned with measuring quality in the setting of serious illness, and in particular aim to prevent the burdening of family members with unnecessarily time-consuming self-report questionnaires. Yet a review suggests that the validity of instruments used in this population is understudied and that some measures used may be unnecessarily long [4]. Fourteen different instruments have been used to measure family satisfaction in palliative care settings [4], several of which were developed specifically for use in such settings. These include the McCusker scale [11], the Satisfaction scale for family members receiving inpatient palliative care [12], and the Family Satisfaction with End-of-Life Care (FAMCARE) for cancer patients [13].

The FAMCARE is a 20-item scale specifically designed to measure family satisfaction with advanced cancer care [14, 15]. An overall score for the original scale is calculated ranging from 1–100, with 100 indicating greater satisfaction with care. It can be administered to family members of seriously ill patients both before and after a patient’s death. This scale has been widely used [1, 16–19] in North America, Australia and Europe to support key findings that families of patients receiving palliative care interventions are more satisfied with care than those receiving usual care.

The FAMCARE is most often used in its original 20-item form, although there has been some work to understand its psychometric properties and develop shortened versions. Table 1 provides a summary of psychometric analyses of the FAMCARE to date. Original development of the scale suggested four domains within the scale using cluster analysis: information giving, availability of care, psychosocial care, and physical patient care [13], although further research suggests it has a unidimensional structure [17, 20–23].

Table 1.

Summary of psychometric analyses of the FAMCARE items across studies

| Investigator | Sample Size | Sample characteristics | Type of Item Analyses | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kristjanson et al. 1986, 1989, 1993 | 210 | Family members of patients from outpatient oncology and homecare in Australia | Cluster analysis, correlations | 4 domains within the scale: information giving, availability of care, psychosocial care, and physical patient care; the internal consistency =.91; test-retest reliability.93 |

| Ringdal et al 2003 | 181 | Family members of patients with advanced cancer from palliative medicine unit in Norway | Factor analysis, a Mokken Scaling Program analysis, and a reliability analysis | Unidimensional scale; Removed 1 item (#14 time to make diagnosis)) |

| Lo et al., 2009a, 2009b | 315 | Family members of patients with advanced cancer receiving outpatient pall care in Canada | Exploratory factor analysis, correlations, Confirmatory factor analysis, reliability tests | Unidimensional scale; Developed 13 item FAMCARE (removed item #1 (pain relief), #9 (doctor’s attention to symptoms), #13 (coordination of care), and #20(availability of doctor to patient))based on factor loadings. Removed Ringdal et al. item 14 and item 6 and 7 as non-relevant in outpatient setting) |

| Aoun et al., 2010 | 497 | Family members of patients from inpatient and outpatient palliative care centers in Australia | Internal consistency and factor analyses of FAMCARE-2 | 17 item FAMCARE-2 scale (Removed #6 availability of hospital bed, modified items to refer to palliative care team instead of doctors or nurses specifically, focused on symptom management instead of pain alone and added new items) |

| Rodriguez et al 2010 | 51 | 51 patients receiving long term care in Veterans Affairs nursing homes or palliative care units in the U.S. | Internal consistency and factor analyses | Removed items #6 (availability of a hospital bed) and #12 (availability of nurses to family) |

| Johnson et al., 2012 | 467 | Family members of patients from oncological, surgical and medical departments from 3 regions in Denmark | Internal consistency analyses, Confirmatory factor analyses for ordinal data using a weighted least squares solution with mean and variance- adjusted chi-square estimation. | The original four scale factor structure (Kristjanson, 1989) resulted in poor fit (CFI=0.83; RMSEA-0.15). However, a unidimensional scale was also not optimal (CFI=0.81; RMSEA=0.16) |

| Carter et al., 2011 | 234 | Caregivers of patients from outpatient oncology and haematology clinics in Australia | Internal consistency analyses; Principal Components Analyses of the four scales; Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA) of all 20 items with oblique rotation. Ad hoc criteria were used to shorten the scale. | Only one component evidenced an eigenvalue above 1 (3.71). EFA of all items yielded two components with eigenvalues greater than 1, accounting for 52% and 7% of the variance Developed 6 item scale with items representing the following factors: information giving (items 3, 4, answers from health professionals; information about side effects); availability of care (items 11, 20; availability of doctors to family, availability of doctors to patient); physical care (items 8 and 14 (speed symptoms are treated; time to make diagnosis). |

| Teresi et al., 2013, 2014 | 1987 | Ethnically diverse family members of inpatients with advanced cancer from 6 US hospitals | Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis for ordinal data using weighted least squares; IRT, DIF | Fewer responses categories needed; evidence for reduction in items; none of the 20 items in the FAMCARE evidenced Differential Item Functioning (DIF) of high magnitude |

A revised 17-item version FAMCARE-2 was developed [24] for use in outpatient settings, with wording changes to refer to symptom management rather than pain management alone; combination of items that refer to care by a doctor or nurse to care by “palliative care team;” addition of items on family emotional well-being, access to practical care assistance and how the team respects the patient’s dignity; and the addition of “not relevant to my situation” as a response choice. Additionally, others have used a shortened 13-item version [25, 26] and a six-item version, FAMCARE-6, which was adapted for use in outpatient oncology settings [21]. Using an ethnically diverse sample, our group used item response theory (IRT) to justify the use of fewer response categories [23]. Furthermore, we found that none of the 20 items in the FAMCARE evidenced differential item functioning (DIF) of high magnitude [27].

The aims of this study were to use item parameters and information functions (defined below) from a family satisfaction item bank to develop a shortened version of the FAMCARE for use in palliative and other care settings for patients with serious illness for research and quality measurement, and to evaluate the psychometric properties of the new short-form.

Methods

Sample

Hospitalized patients with advanced cancer were recruited from six hospitals: Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY; Virginia Commonwealth University-Massey Cancer Center, Richmond, VA; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA; Fairview Health System, Minneapolis, MN; Mount Carmel Health System, Columbus Ohio, and Froedtert Hospital of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI. The goal was to study outcomes for patients and families who receive inpatient palliative care consultation team services. Patients were required to meet the following criteria: age 18 and older, diagnosis of metastatic solid tumor or central nervous system malignancies, locally advanced head and neck or pancreas cancers, metastatic melanoma, or transplant-ineligible lymphoma and myeloma. Participants were excluded if their attending physician did not give permission to recruit their patients; did not speak English; had a diagnosis of dementia; were admitted for routine chemotherapy; died or were discharged within 48 hours of admission; or had previously received palliative care consultation. During hospitalization, patients identified the family member who was the primary contact person. Patients were followed until hospital discharge or death and post-discharge surveys were conducted via telephone with patients and/or family members. The FAMCARE scale was administered to family members by a research nurse via telephone one week post discharge. If a patient died during the hospitalization, the family member was contacted by telephone two months after the death and administered the FAMCARE.

Statistical Approach

A previous analysis [23] of the total sample and all five response categories was performed using IRT to develop an item bank for family satisfaction items. The graded response model [28] was used to evaluate the measure and to provide item parameters for the item bank on family satisfaction and care transitions; such IRT methods have been used to model health-related constructs [29]. The category response functions were examined in order to determine whether any categories were overlapping and if they provided unique information. For all items, the lower categories were overlapping such that the probability of response was similar for these three categories: very dissatisfied, dissatisfied, and undecided, indicating little if any unique information provided by these categories. Therefore, it was determined that categories could be collapsed (see Teresi et al. (23) for further details).

The estimates for the discrimination and severity (location) parameters (a and b, respectively) were evaluated. The discrimination parameter informs about the strength of the relationship between an item and the trait measured, e.g., satisfaction. The severity parameter indicates at what point along the satisfaction continuum, denoted θ (theta), the item maximally discriminates (separates or differentiates among examinees at different satisfaction levels or groups). These parameters are useful in determining which items are most informative in terms of the measurement of the underlying construct, satisfaction. IRTPRO [30] was used for IRT parameter estimation and tests of model fit.

Because item banks require items that perform in an equivalent manner across groups differing in factors such as age, education, gender and race, analyses of differential item functioning was performed on the items before placement in the bank. As discussed above, these analyses, reported elsewhere [27] showed that the items were relatively DIF-free for the groups examined, and thus could be placed in the bank.

The information functions, based on these parameter estimates were used to select the best short-form family satisfaction measures from the item bank. Item information plays a key role in item banks because it is a basis for selection of items for short forms and computerized adaptive tests. Information has a reciprocal relationship with error of measurement; items provide more information when the slope (a) parameter is higher and the standard error is lower. The test (scale) information, which is the sum across items of the item information, informs about the reliability of the total measure. Information varies across levels of the underlying attribute, satisfaction in this case; high scale information values are indicative of measures that evidence relatively high reliability. Subsequent factor analyses were conducted to examine the dimensionality of the short-form measures and to produce the reliability analyses. A Schmid-Leiman (S-L) [31] transformation using the Psych R package [32] was performed in order to find an alternative set of group factors for the bi-factor model [33]. Polychoric correlations were estimated, and the final bi-factor model was run using M-PLUS [34]. The explained common variance (ECV), the percent of observed variance explained, was estimated to provide information about whether the observed variance-covariance matrix is close to unidimensionality [35]. Reliability was evaluated with classical methods as well as using McDonald’s Omega Total [36] (ωt,), an estimate based on the proportion of total common variance explained. Reliability analyses were performed for the total sample as well as for gender, education, race and age subgroups.

Results

The original sample size was 2146; 140 patients whose primary language was not English were excluded from the sample because the DIF testing was only performed with respect to English speakers. After omission of respondents (from among the remaining 2006) who responded to less than 50% of items, the analytic sample comprised 1983 patients. Among them, 56.2% of patients were female; the mean (SD) age was 59.9.1 (11.8) years, and 35.1% were 65 years of age or older. The mean (SD) educational level was 13.6 (3.2) years; 19.6% were non-Hispanic Black and 76.5% were non-Hispanic White.

Because of sparse data in the very dissatisfied categories, equivocal classification in terms of the “undecided” category, and the results of IRT analyses [23], items were coded as ordinal and collapsed as follows: “very satisfied” responses were coded as 2, “satisfied” as 1 and indecision or “dissatisfaction” as 0.

Examination of Information Function Data from the Item Bank

Examination of the information function data from the item bank identified 10 items that were most informative for the 10-item short-form and five items for the five-item short-form (Supplemental Table 1, available at jpsmjournal.com). The items identified as maximally informative in order of magnitude were: “The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor”; “How thoroughly the doctor assesses the patient’s symptoms”; “Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms”; “Availability of the doctor to the patient”; “Information given about the patient’s tests”; “Information given about how to manage the patient’s pain”; “The way the family is included in treatment and care decisions”; “Time required to make diagnosis”; “Availability of doctors to the family”; and “Coordination of care.”

The information functions were bimodal, producing maximal information at two modes, at about θ = −1.5 and θ = 0.6. Information at these two modes was examined in order to inform the decision about the number of items for the short-form measures. For both modes, the maximal information ranged from 1.94 to 3.37 for the 10-item set (the next highest maximal information value was 1.57) and from 2.51 to 3.37 on the five item set (the next highest maximal information value was 2.29). The decision to select 10 and five, respectively, was made because this is the number of items after which the change (diminution) in maximal information was largest.

Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses

The simple first to second eigenvalue ratio test supported essential unidimensionality of both the 10-item and five-item versions of the measure (total sample: eigenvalues of 7.42 to 0.46 and 4.06 to 0.34 for the 10- and five-item scales, respectively, representing ratios of the first to second eigenvalues of 16 and 12 to 1, respectively (Supplemental Table 2, available at jpsmjournal.com). The confirmatory factor analyses using MPlus resulted in comparative fit indices of 0.987 and 0.999 for the 10- and five-item one-factor solution and root mean square errors of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.105 and 0.072; the results using the IRT model were 0.100 and 0.040, respectively. Although the RMSEAs were somewhat smaller for the two-factor solution, the difference was not appreciable (Supplemental Table 3, available at jpsmjournal.com).

Essential Unidimensionality

The loadings on the one-factor solution were very high as were the loadings on the first factor of the two-factor solution for both the ten- and five-item set, supporting an essentially unidimensional structure (Table 2). The essential unidimensionality estimates were high; the ECV from the Psych R program was 63.83 and 71.95 for the ten- and five- item scales, respectively, and ranged from 61.69 to 66.71 for the 10-item scale and from 69.97 to 74.09 for the five-item scale across ethnic racial, education, gender and relationship groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

FAMCARE ten and five item sets: Item factor loadings (λ) from the unidimensional solution (MPLUS) (n=1983)

| Item Description | One Factor λ (s.e.) | One Factor λ (s.e.) |

|---|---|---|

| 9. Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms | 0.84 (0.01) | 0.83 (0.01) |

| 11. Availability of doctors to the family | 0.84 (0.01) | -- |

| 13. Coordination of care | 0.80 (0.01) | -- |

| 14. Time required to make diagnosis | 0.82 (0.01) | -- |

| 15. The way the family is included in treatment and care decisions | 0.83 (0.01) | -- |

| 16. Information given about how to manage the patient’s pain | 0.83 (0.01) | -- |

| 17. Information given about the patient’s tests | 0.86 (0.01) | 0.82 (0.01) |

| 18. How thoroughly the doctor assesses the patient’s symptoms | 0.88 (0.01) | 0.90 (0.01) |

| 19. The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor | 0.91 (0.01) | 0.94 (0.01) |

| 20. Availability of the doctor to the patient | 0.88 (0.01) | 0.88 (0.01) |

Table 3.

FAMCARE ten and five item sets: Reliability statistics alpha, omega and ECV for demographic subsets (Results are from the “Psych” R package)

| Sample | Ten item set | Five item set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Omega Total (ωt) | ECV | Alpha | Omega Total (ωt) | ECV | |

| Total Sample (n=2123) | 0.937 | 0.961 | 63.830 | 0.902 | 0.942 | 71.949 |

| Age 64 & Under (n=1287) | 0.933 | 0.959 | 62.601 | 0.897 | 0.939 | 71.029 |

| Age 65 & Over (n=696) | 0.944 | 0.968 | 66.556 | 0.912 | 0.951 | 74.094 |

| Females (n=1115) | 0.938 | 0.963 | 64.516 | 0.904 | 0.945 | 72.459 |

| Males (n=865) | 0.934 | 0.960 | 62.988 | 0.899 | 0.940 | 71.317 |

| Non-Hispanic Black (n=388) | 0.933 | 0.965 | 63.247 | 0.903 | 0.951 | 72.249 |

| Non-Hispanic White (n=1517) | 0.937 | 0.962 | 63.785 | 0.901 | 0.942 | 71.742 |

| Less Than High School (n=317) | 0.939 | 0.965 | 64.693 | 0.911 | 0.952 | 73.862 |

| High School (n=666) | 0.944 | 0.969 | 66.707 | 0.912 | 0.951 | 74.060 |

| Some College & Above (n=992) | 0.931 | 0.957 | 61.685 | 0.892 | 0.935 | 69.970 |

| Relative Living With Patient (n=862) | 0.939 | 0.964 | 64.535 | 0.903 | 0.946 | 72.164 |

| Relative NOT Living With Patient (n=696) | 0.934 | 0.960 | 63.185 | 0.902 | 0.939 | 71.878 |

| Friend (n=208) | 0.937 | 0.966 | 64.371 | 0.907 | 0.950 | 72.974 |

McDonald’s omega total (ωt)

IRT Analyses for the Short-Form IRT Scales

Table 4 shows that the IRT discrimination (a) parameters estimated with IRTPRO for the 10- item scale ranged from the lowest, 2.50 (“coordination of care”) to the highest, 4.25 (“the way tests and treatments are followed by the doctor”). The lowest discrimination parameter for the five-item scale was 2.81 and the highest, 5.30 (Table 4). The range of the location parameters reflects the overall relatively high satisfaction rates, with mean scores between 1 (satisfied) and 2 (very satisfied).

Table 4.

FAMCARE ten and five item sets: IRT item parameters and standard error estimates (IRTPRO) (n=1983)

| Ten Item Set | Five Item Set | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Description | a | s.e.a | b1 | s.e. | b2 | s.e. | a | s.e.a | b1 | s.e. | b2 | s.e. |

| Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms | 2.99 | 0.14 | −1.63 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 2.82 | 0.14 | −1.70 | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.04 |

| Availability of doctors to the family | 2.74 | 0.12 | −1.35 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.04 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Coordination of care | 2.50 | 0.11 | −1.48 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.05 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Time required to make diagnosis | 2.78 | 0.13 | −1.39 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.05 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| The way the family is included in treatment and care decisions | 2.78 | 0.13 | −1.38 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.04 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Information given about how to manage the patient’s pain | 2.77 | 0.13 | −1.47 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.05 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Information given about the patient’s tests | 3.17 | 0.15 | −1.38 | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.04 | 2.81 | 0.13 | −1.46 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.04 |

| How thoroughly the doctor assesses the patient’s symptoms | 3.58 | 0.18 | −1.52 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 4.03 | 0.23 | −1.53 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.03 |

| The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor | 4.25 | 0.23 | −1.38 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.04 | 5.30 | 0.40 | −1.38 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.04 |

| Availability of the doctor to the patient | 3.49 | 0.17 | −1.42 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.04 | 3.53 | 0.18 | −1.45 | 0.05 | 0.52 | 0.04 |

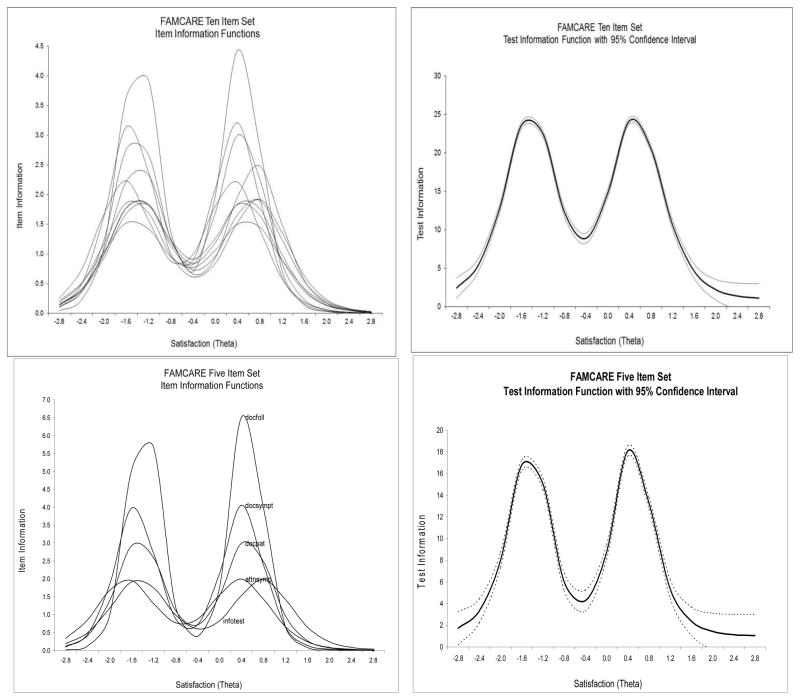

As shown in Fig. 1, the item and scale information functions (estimated using IRTPRO) for the two versions of the scale are bimodal with two peaks where most information is provided. The TIF values at those nodes are high (18 and 25, respectively for the five- and 10- item scales), corresponding to overall scale reliabilities >0.90. The first peak for the 10-item scale for individual items is in the theta area between −1.6 to −1.3 translating into the range for the sum score between 3 and 5 on the satisfaction scale (range of 0–20). The second peak is in the theta range from 0.3 to 0.8 or the sum score range between 13.5 and 16.5 for this sample. For the five-item scale, the peaks are between −1.7 and −1.4 and 0.4 and 0.8, corresponding to from 2 to 3 and from 7 to 8 on the five-point scale (range of 0–10). Most information was provided in the range indicative of either dissatisfaction or high satisfaction. Less information was provided in the range of scores indicative of reporting being “just” satisfied (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

FAMCARE ten and five item sets: Item and test information functions

Reliability

Different reliability estimates were obtained from several methods. Based on the IRTPRO results, the estimates of reliability were calculated along the theta continuum and ranged from 0.96 at theta −1.6, −1.2, and at 0.4 and to a low of 0.69 at the highest range (theta=2.0) (Table 5). For the five-item scale, the reliability estimates ranged from 0.84 to 0.95 across most of the range of theta, but were lower at the tails (−2.4 and 2.0 where the estimates were 0.77 and 0.59). In general, reliability was adequate (>0.80) for all levels of theta for which subjects had scores (θ from −2.4 to 2.0) (Table 5). The average reliability estimate was 0.90 for the 10-item scale in comparison to the total 20-item scale (0.92) reported by Teresi et al. (2013). As expected, the overall reliability estimate was lower (0.84) for the five-item scale.

Table 5.

FAMCARE ten and five item sets: Reliability statistics at varying levels of the attribute (theta) estimate based on results of the IRT analysis (IRTPRO)

| Satisfaction (Theta)* | Reliability | |

|---|---|---|

| Ten item set | Five item set | |

| −2.4 | 0.84 | 0.77 |

| −2.0 | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| −1.6 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| −1.2 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| −0.8 | 0.92 | 0.86 |

| −0.4 | 0.90 | 0.81 |

| 0.0 | 0.94 | 0.90 |

| 0.4 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| 0.8 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| 1.2 | 0.91 | 0.84 |

| 1.6 | 0.83 | 0.70 |

| 2.0 | 0.69 | 0.59 |

| Overall (Average) | 0.90 | 0.84 |

Range of the theta distribution at the extremes is limited to the points where there are any responders

The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliability estimate as well as the standardized alpha for the 10-item scale was 0.94 and 0.90 for the five-item scale (Supplemental Table 4, available at jpsmjournal.com). Corrected item-total correlations ranged from 0.70 to 0.81 for the 10-item scale and from 0.70 to 0.82 for the five-item scale (Supplemental Table 4). Examining the reliability estimates across gender, education, race and age groups showed good performance of the short forms. The alphas for the 10-item set across different age, gender, education, racial and relationship groups ranged from 0.93 to 0.94 for the 10-item scale and from 0.89 to 0.91 for the five-item scale (Table 3). The omega total estimates were very high, ranging from 0.94 to 0.97 across the groups and scales (Table 3).

Distributional Characteristics

Examining the distributional characteristics of the measure, the mean sum score was 12.00 (SD=4.69) for the 10-item scale with the median of 10; the mean theta was −0.01 (0.94) with the median of −0.41. Skewness statistics were 0.23 (0.06) and 0.36 (0.06) and kurtosis was −0.39 (0.11) and 0.30 (0.11). The Kolmogorow-Smirnov test of normality was 0.19, P<0.001 and 0.19, P<0.001 (Supplemental Table 5, available at jpsmjournal.com). For the five-item scale, the mean sum score was 6.14 (2.46).

The majority of respondents received a score of 10 on the 10-item scale and 5 on the five-item scale (Tables 6 and 7). These values correspond to theta values of −0.41 and −0.42, respectively, on the two scales. The theta score is mapped to the sum score. The mean theta score (0) corresponds to a score of about 12 on the 10-item scale and 6 on the five-item scale. A theta score of one-half standard deviation above the mean corresponds to a scale score of about 15 (reflecting roughly the upper third of the distribution) for the 10-item scale and 8 for the five- item scale. Thus potential cut scores might be 15 and above and 8 and above for the two scales, respectively.

Table 6.

FAMCARE ten item set: Distribution of the summary score mapped to the satisfaction estimate (theta) (n=1983)

| Summed Score | N | % | Cum. % | EAP*[θ|x] | SD[θ|x] | Modeled % | Modeled Cum. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 17 | 0.9% | 0.9% | −2.424 | 0.425 | 1.3% | 1.3% |

| 1 | 12 | 0.6% | 1.5% | −2.053 | 0.302 | 1.3% | 2.6% |

| 2 | 21 | 1.1% | 2.5% | −1.830 | 0.250 | 1.3% | 4.0% |

| 3 | 22 | 1.1% | 3.6% | −1.661 | 0.225 | 1.4% | 5.4% |

| 4 | 23 | 1.2% | 4.8% | −1.515 | 0.214 | 1.6% | 7.0% |

| 5 | 25 | 1.3% | 6.1% | −1.377 | 0.213 | 1.9% | 8.9% |

| 6 | 45 | 2.3% | 8.3% | −1.234 | 0.221 | 2.4% | 11.3% |

| 7 | 55 | 2.8% | 11.1% | −1.075 | 0.239 | 3.2% | 14.5% |

| 8 | 77 | 3.9% | 15.0% | −0.885 | 0.267 | 4.8% | 19.3% |

| 9 | 141 | 7.1% | 22.1% | −0.656 | 0.294 | 8.0% | 27.3% |

| 10 | 607 | 30.6% | 52.7% | −0.408 | 0.299 | 13.0% | 40.3% |

| 11 | 156 | 7.9% | 60.6% | −0.162 | 0.284 | 9.9% | 50.3% |

| 12 | 104 | 5.2% | 65.8% | 0.054 | 0.255 | 7.2% | 57.5% |

| 13 | 71 | 3.6% | 69.4% | 0.232 | 0.231 | 5.7% | 63.2% |

| 14 | 55 | 2.8% | 72.2% | 0.386 | 0.218 | 4.9% | 68.2% |

| 15 | 46 | 2.3% | 74.5% | 0.528 | 0.214 | 4.5% | 72.7% |

| 16 | 54 | 2.7% | 77.2% | 0.671 | 0.220 | 4.4% | 77.1% |

| 17 | 54 | 2.7% | 79.9% | 0.826 | 0.236 | 4.5% | 81.5% |

| 18 | 80 | 4.0% | 84.0% | 1.011 | 0.268 | 4.8% | 86.4% |

| 19 | 72 | 3.6% | 87.6% | 1.269 | 0.334 | 5.7% | 92.1% |

| 20 | 246 | 12.4% | 100.0% | 1.738 | 0.496 | 7.9% | 100.0% |

EAP is the expected a posteriori estimate (mean of the posterior distribution of theta (θ), conditional on x (the observed response pattern)).

Table 7.

FAMCARE five item set: Distribution of the summary score mapped to the satisfaction estimate (theta) (n=1983)

| Summed Score | N | % | Cum. % | EAP*[θ|x] | SD[θ|x] | Modeled % | Modeled Cum. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30 | 1.5% | 1.5% | −2.232 | 0.440 | 2.3% | 2.3% |

| 1 | 42 | 2.1% | 3.6% | −1.808 | 0.310 | 2.4% | 4.7% |

| 2 | 39 | 2.0% | 5.6% | −1.526 | 0.270 | 2.7% | 7.4% |

| 3 | 72 | 3.6% | 9.2% | −1.254 | 0.287 | 3.8% | 11.2% |

| 4 | 121 | 6.1% | 15.3% | −0.887 | 0.360 | 8.1% | 19.3% |

| 5 | 822 | 41.5% | 56.8% | −0.420 | 0.387 | 28.1% | 47.4% |

| 6 | 175 | 8.8% | 65.6% | 0.016 | 0.337 | 13.2% | 60.6% |

| 7 | 99 | 5.0% | 70.6% | 0.345 | 0.278 | 8.5% | 69.1% |

| 8 | 97 | 4.9% | 75.5% | 0.618 | 0.276 | 7.6% | 76.7% |

| 9 | 137 | 6.9% | 82.4% | 0.936 | 0.338 | 9.1% | 85.8% |

| 10 | 349 | 17.6% | 100.0% | 1.481 | 0.525 | 14.2% | 100.0% |

EAP is the expected a posteriori estimate (mean of the posterior distribution of theta (θ), conditional on x (the observed response pattern)).

Discussion

It is particularly important to reduce unnecessary burden for family members of patients with serious illness. Thus, IRT results and information from an item bank were used to create short forms of the widely used 20-item FAMCARE satisfaction scale. Both the 10- and five- item scales are shorter and use fewer response categories, resulting in a more efficient scale that will reduce respondent burden considerably. The 10-item scale is slightly more precise and measures across a larger range of theta. Researchers concerned about power to detect an effect size may opt for the 10-item scale, which is estimated to have somewhat higher reliability. However, if time and respondent burden are major concerns, the five-item scale is adequate, and can be administered very quickly. Prior research showed very little differential item functioning (DIF) across these items [27]. The one item that showed more salient DIF is not included in these short-form measures. Thus, these measures also can be recommended as relatively culture-fair or invariant across groups differing in patient gender, age, education and race (black or white) although future work should examine DIF among individuals of Hispanic status and non-English speakers.

Although other psychometric techniques, e.g., factor analysis, have been used to reduce the original 20-item scale (Table 1), to our knowledge, no other studies have analyzed the FAMCARE using IRT. Our findings regarding the selection of specific items can be compared with those selected for other shortened versions of the FAMCARE. Our analyses supported the deletion of two items by Rodriguez and colleagues (22): “availability of nurses to the family” and “availability of hospital bed,” based on the information function analyses. Carter and colleagues (21) developed a six-item scale with items representing the following factors: information giving; availability of care; and physical care. Based on our analyses of the information functions derived from IRT, the items selected in the Carter et al. study included one highly informative item, one uninformative item, and four moderately informative items. Our analyses supported the findings of Carter et al. in not including “the patients’ pain relief,” but the item “information given about management of pain” was among the six most informative items. The item related to satisfaction with “the patients’ pain relief” also evidenced some minor level of DIF for race and education. Although the magnitude of DIF was low, it was flagged as an item that may not perform in the same manner across groups differing in race and education.[27] Our analyses supported inclusion of “availability of the doctor to the patient”. Our analyses did not support inclusion of “side effects” and “speed with which symptoms were treated.”

Our findings show that the five most informative items are related to the perception of the doctor’s care of the patient. This is noteworthy given how palliative care is routinely delivered by multidisciplinary care teams. Although these items are technically the most discriminating and related to the underlying trait, satisfaction with care, this does not necessarily mean that communication with other members of the care team is not important for family members. Interestingly, 20% of the original FAMCARE scale on which this analysis was based included items related to the doctor; in contrast, the FAMCARE only has one item specifically about ‘nurses and one item focused on “health care professionals” in general. Furthermore, this sample consisted of hospitalized patients with advanced metastatic cancer who may have 24-hour nurse availability. The authors of a revised version of the FAMCARE changed the wording related to “care by doctor” to “care by the palliative care team” to reflect better the multidisciplinary team-based care [24]. This language also may be more appropriate in other care settings, e.g., hospice. Future work could examine the performance of the reworded items.

There are several limitations to note. This work was restricted to patients with advanced cancer and the psychometric properties of the FAMCARE in other settings of serious illness should be further studied. Additionally, we excluded 17 cases from our analytic sample because of missing data. Further, as previously noted, although DIF analyses were used to provide support for the invariance of items across groups differing in patient gender, age, education and race (black or white); we were unable to examine DIF among individuals of Hispanic status and non-English speakers.

Assessing satisfaction with care is critical to ensuring high quality care in the setting of serious illness. Both short-form scales perform very well and can be easily administered in diverse clinical settings (hospital, home, hospice, long-term care). These short-form scales were developed in a setting of advanced cancer care, among both patients who received specialized inpatient palliative care services and those who received usual inpatient care. These scales also are appropriate for assessing family satisfaction with care in the setting of other types of serious illness. The use of these short-form scales should reduce burden of assessing satisfaction for family members in both clinical and research settings and can decrease barriers to measuring and ensuring high quality palliative care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute, Grant 5R01CA116227-05. Support for these analyses was provided by the Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center: National Institute on Aging, P30, AG028741. Dr. Morrison was supported by the National Institute on Aging, Grant 5K24AG022345, and the National Palliative Care Research Center. Dr. Ornstein was supported by the National Institute on Aging, Grant K01AG047923.

Appendix. Short-Form FAMCARE Scales

10-Item Short-Form FAMCARE Scale

Please indicate how satisfied you are with the care received by your_____(relative, friend, other). Would you say that you are “very satisfied,” “satisfied” or “not satisfied” with each of the following:

| How satisfied are you with the following: | Very Satisfied | Satisfied | Not Satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms | |||

| 2. Availability of doctors to the family | |||

| 3. Coordination of care | |||

| 4. Time required to make diagnosis | |||

| 5. The way the family is included in treatment and care decisions | |||

| 6. Information given about how to manage the patient’s pain | |||

| 7. Information given about the patient’s tests | |||

| 8. How thoroughly the doctor assesses the patient’s symptoms | |||

| 9. The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor | |||

| 10. Availability of the doctor to the patient |

Five-Item Short-Form FAMCARE Scale

Please indicate how satisfied you are with the care received by your_____(relative, friend, other). Would you say that you are “very satisfied,” “satisfied” or “not satisfied” with each of the following:

| How satisfied are you with the following: | Very Satisfied | Satisfied | Not Satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms | |||

| 2. Information given about the patient’s tests | |||

| 3. How thoroughly the doctor assesses the patient’s symptoms | |||

| 4. The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor | |||

| 5. Availability of the doctor to the patient |

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Kassa S. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care for cancer patients in a cluster randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Do specialist palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 1998;12:317–332. doi: 10.1191/026921698676226729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson EK, Salisbury C, Bosanquet N, et al. Patient and carer preference for, and satisfaction with, specialist models of palliative care: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 1999;13:197–216. doi: 10.1191/026921699673563105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson PL, Trauer T, Graham S, et al. A systematic review of instruments related to family caregivers of palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 2010;24:656–668. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Lorenz KA, et al. A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:124–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andershed B. Relatives in end-of-life care--part 1: a systematic review of the literature the five last years, January 1999–February 2004. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1158–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milberg A, Strang P, Carlsson M, Borjesson S. Advanced palliative home care: next-of-kin’s perspective. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:749–756. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stajduhar KI, Martin W, Cairns M. What makes grief difficult? Perspectives from bereaved family caregivers and healthcare providers of advanced cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:277–289. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams AL, McCorkle R. Cancer family caregivers during the palliative, hospice, and bereavement phases: a review of the descriptive psychosocial literature. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9:315–325. doi: 10.1017/S1478951511000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tierney RM, Horton SM, Hannan TJ, Tierney WM. Relationships between symptom relief, quality of life, and satisfaction with hospice care. Palliat Med. 1998;12:333–344. doi: 10.1191/026921698670933919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCusker J. Development of scales to measure satisfaction and preferences regarding long-term and terminal care. Med Care. 1984;22:476–493. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198405000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morita T, Chihara S, Kashiwagi T. A scale to measure satisfaction of bereaved family receiving inpatient palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16:141–150. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm514oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristjanson LJ. Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE Scale: measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:693–701. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90066-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristjanson LJ. Quality of terminal care: salient indicators identified by families. J Palliat Care. 1989;5:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristjanson LJ. Indicators of quality of palliative care from a family perspective. J Palliat Care. 1986;1:8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ. 20048;170:1795–1801. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S. Measuring quality of palliative care: psychometric properties of the FAMCARE Scale. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:167–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1022236430131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudgeon DJ, Knott C, Eichholz M, et al. Palliative Care Integration Project (PCIP) quality improvement strategy evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Follwell M, Burman D, Le LW, et al. Phase II study of an outpatient palliative care intervention in patients with metastatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:206–213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnsen AT, Ross L, Petersen MA, Lund L, Groenvold M. The relatives’ perspective on advanced cancer care in Denmark. A cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:3179–3188. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter GL, Lewin TJ, Gianacas L, Clover K, Adams C. Caregiver satisfaction with out-patient oncology services: utility of the FAMCARE instrument and development of the FAMCARE-6. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:565–572. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0858-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez KL, Bayliss NK, Jaffe E, Zickmund S, Sevick MA. Factor analysis and internal consistency evaluation of the FAMCARE scale for use in the long-term care setting. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:169–176. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teresi JA, Ornstein K, Ocepek-Welikson K, Ramierz M, Siu A. Performance of the Family Satisfaction with the End-of-Life Care (FAMCARE) measure in an ethnically diverse cohort: psychometric analyses using item response theory. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1988-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aoun S, Bird S, Kristjanson LJ, Currow D. Reliability testing of the FAMCARE-2 scale: measuring family carer satisfaction with palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24:674–681. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo C, Burman D, Hales S, et al. The FAMCARE-Patient scale: measuring satisfaction with care of outpatients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3182–3188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo C, Burman D, Rodin G, Zimmerman C. Measuring patient satisfaction in oncology palliative care: psychometric properties of the FAMCARE-patient scale. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:747–752. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9494-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teresi JA, Ocepek-Welikson K, Ramirez M, et al. Performance of the Family Satisfaction with the End-of-Life Care (FAMCARE) measure in an ethnically diverse cohort: tests of differential item functioning. Palliat Med. 2014 Aug 26; [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samejima F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monograph Supplement. 1969:17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teresi JA, Kleinman M, Ocepek-Welikson K. Modern psychometric methods for detection of differential item functioning: application to cognitive assessment measures. Stat Med. 2000;19:1651–1683. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1651::aid-sim453>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cai L, Thissen D, du Toit S. IRTPRO: Flexible, multidimensional, multiple categorical IRT Modeling [Computer software] Chicago: Scientific Software International Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmid J, Leiman J. The development of heirarchical factor solutions. Psychometrika. 1957;22:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rizopoulus D. ltm: Latent Trait Models under IRT. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reise SP, Moore TM, Haviland MG. Bifactor models and rotations: exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. J Pers Assess. 2010;92:544–559. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.496477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthén L, Muthén B, editors. M-PLUS users guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 1999–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sijtsma K. On the use, misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s Alpha. Psychometrika. 2009;74:107–120. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonald RP. The theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1970;23:1–21. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.