Abstract

Steroid positive-feedback activation of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) neuroendocrine axis propagates the pre-ovulatory LH surge, a crucial component of female reproduction. Our work shows that this key event is restrained by inhibitory metabolic input from hindbrain A2 noradrenergic neurons. GnRH neurons express the ultra-sensitive energy sensor adenosine 5’-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK); here, we investigated the hypothesis that GnRH nerve cell AMPK and peptide neurotransmitter responses to insulin-induced hypoglycemia are controlled by hindbrain lack of the oxidizable glycolytic endproduct L-lactate. Data show that hypoglycemic inhibition of LH release in steroid-primed ovariectomized female rats was reversed by coincident caudal hindbrain lactate infusion. Western blot analyses of laser-microdissected A2 neurons demonstrate hypoglycemic augmentation [Fos, estrogen receptor-beta (ER- ), phosphoAMPK (pAMPK)] and inhibition [dopamine-beta-hydroxylase, GLUT3, MCT2] of protein expression in these cells, responses that were normalized by insulin plus lactate treatment. Hypoglycemia diminished rostral preoptic GnRH nerve cell GnRH-I protein and pAMPK content; the former, but not the latter response was reversed by lactate. Results implicate caudal hindbrain lactoprivic signaling in hypoglycemia-induced suppression of the LH surge, demonstrating that lactate repletion of that site reverses decrements in A2 catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme and GnRH neuropeptide precursor protein expression. Lack of effect of lactate on hypoglycemic patterns of GnRH AMPK activity suggests that this sensor is uninvolved in metabolic-inhibition of positive-feedback - stimulated hypophysiotropic signaling to pituitary gonadotropes.

Keywords: luteinizing hormone surge, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, laser-microdissection, Western blot, phosphoAMPK, A2 noradrenergic neurons

Introduction

Neural regulation of female reproductive function is tightly coupled with cellular energy metabolism, as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) output to the anterior pituitary is repressed by substrate fuel shortage [Clarke et al., 1990; Chen et al., 1992]. Steroid positive-feedback activation of the GnRH-pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) neuroendocrine axis triggers a critical mid-cycle signal to the ovary that controls oogenesis, ovulation, and corpus luteum function. Energy deficiency is a key cause of reduced frequency or cessation of ovulation in women [Crosignani, 2006]. Connectivity of preoptic GnRH neurons with extra-preoptic metabolic sensors is affirmed by the capacity of pharmacological induction of glucopenia within the hindbrain to reverse steroid positive-feedback activation of those cells and to suppress the LH surge [Briski and Sylvester, 1998]. Hindbrain caudal dorsal vagal complex A2 noradrenergic neurons participate in estrogen negative- and positive-feedback regulation of LH secretion, responding to these dualistic signals by release of norepinephrine into the medial preoptic area at basal versus elevated rates [Demling et al., 1985; Mohankumar et al., 1994; Szawka et al., 2013]. Evidence that A2 cells express estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) and -beta (ERβ) proteins [Ibrahim et al., 2013] and biomarkers for metabolic sensing, e.g. glucokinase, KATP, and the ultra-sensitive energy sensor, adenosine 5’-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [Briski et al., 2009; Cherian and Briski, 2011; Ibrahim et al., 2013], suggests that these neurons function to integrate steroidal and metabolic stimuli. Indeed, we reported show that hindbrain glucopenia regulates markers of A2 neuron function, and attenuates estradiol-stimulated noradrenergic input to the reproductive neuroendocrine axis in response to metabolic shortfall [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014]. As effects of intra-hypothalamic glucose anti-metabolite administration on LH secretion are not known, the prospect that forebrain metabolic sensors may also regulate this hormone cannot be discounted. Nonetheless, function of the hypothalamus as a conduit for hindbrain metabolic input to GnRH neurons warrants investigation. Indeed, available studies implicate hypothalamic arcuate nucleus endorphinergic mu opioid receptor signaling in inhibitory LH secretory responses to hindbrain glucopenia [Singh and Briski, 2004].

Metabolism of glucose, the primary energy source to the brain, is compartmentalized by cell-type and involves metabolite exchange between astrocytes and neurons [Laming et al., 2000]. The astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle hypothesis (ANLSH) proposes that glucose is acquired from the circulation mainly by astrocytes, and either is stored as glycogen, a complex branched polymer, or catabolized to the oxidizable fuel L-lactate for trafficking to neurons [Pellerin and Magistretti, 1994; Pellerin et al., 1998]. Lactate is released into the extracellular space as a vital energy substrate for nerve cell aerobic respiration. Despite high energy needs, neurons exhibit a truncated glycolytic pathway that favors pentose phosphate metabolism and anti-oxidative protection over energy production [Barros, 2013]. Nerve cell reliance upon astrocyte-derived lactate is indicated by its preferred use over glucose as an in vivo energy substrate when both substrates are available [Wyss et al., 2011]. Our studies show that lactate utilization is a critical monitored variable in hindbrain monitoring of nerve cell metabolic stasis [Patil and Briski, 2005]. Insulin-induced hypoglycemia diminishes extracellular glucose levels in the brain [Silver IA, Ereci ska M, 1998], and reduces tissue lactate levels in the hindbrain A2 neuron area [Shrestha et al., 2014].

Insulin-induced hypoglycemia suppresses pituitary LH secretion in several species, including the rat [Goubillon and Thalabard, 1996; Cagampang et al., 1997; He et al., 1999; Cates et al., 2004], sheep [Clarke et al., 1990; Medina et al., 1998; Adam and Findlay, 1998], cow [Rutter and Manns, 1987], monkey [Chen et al., 1992; Heisler et al., 1993; Lado-Abeal et al., 2002], and human [Oltmanns et al., 2001]. The work performed here utilized combinatory in situ immunocytochemistry, single-cell laser-microdissection, and high-sensitivity Western blotting to address the hypothesis that insulin-induced hypoglycemia-associated lactoprivation of the caudal hindbrain, including A2 neurons, regulates GnRH AMPK activity and neuropeptide transmitter expression. The current experimental design allowed us to compare A2 and GnRH nerve cell AMPK responses to 1) physiological glucopenia (e.g. hypoglycemia) versus 2) pharmacological glucopenia (and associated hyperglycemia) achieved by caudal fourth ventricular glucose anti-metabolite administration, an experimental approach we used in previous work [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014], during steroid positive-feedback. An important goal of the present work was to reconcile the role of GnRH nerve cell AMPK in the in vivo context of metabolic restraint of pituitary LH secretion. Recent in vitro studies suggest that GnRH neurons may engage in energy self-monitoring to regulate cell function. Glucose decrements in preoptic area slice preparations are reported to inhibit GnRH nerve cell firing [Zhang et al., 2007], a response that is abolished by AMPK inhibition [Roland and Moenter, 2011]. Also, immortalized mouse hypothalamic GT1-7 cells express AMPK and exhibit diminished GnRH release upon treatment with AMPK activators [Coyral-Castel et al., 2088; Wen et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2011]. We previously observed a decline in rostral preoptic GnRH nerve cell AMPK activation during pharmacological glucoprivic suppression of in vivo LH release [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014], results that imply that afferent signals of hindbrain glucopenia are prioritized over hyperglycemic deactivation of this local sensor in governing LH. Implementation of our characterized protocol for hindbrain lactate repletion during hypoglycemia [Gopal and Briski, 2005; Gujar et al., 2014; Shrestha et al., 2014] allowed us to examine here the working premise that GnRH AMPK activity is increased in response to glycemic decline, yet normalized by hindbrain signaling of metabolic stability.

Methods and Materials

Experimental Design

Adult female Sprague Dawley rats (200-300 g bw) were obtained from the ULM School of Pharmacy in-house breeding colony (breeders were purchased from Harlan Laboratories, Inc.; Madison, WI.). Animals were treated in accordance with NIH guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals, as approved by the ULM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were maintained under a 14hr light:10 hr dark schedule, and allowed free access to standard laboratory rat chow (Harlan Teklad LM-485; Harlan Industries) and water. On day 1, animals were implanted with a 26-gauge stainless-steel cannula guide (Prod no. C315G/SPC; Plastic One, Inc., Roanoke, VA) into the caudal fourth ventricle (CV4) [Coordinates: 0 mm lateral to midline; 13.3 mm posterior to bregma; 6.1 mm ventral to skull surface] under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia (0.1mL/100 g bw ip, 90 mg ketamine: 10mg xylazine/mL; Putney, Inc., Portland, ME; LLOYD laboratories Inc., Shenandoah, IO), and transferred to individual cages. On day 7, each rat was bilaterally ovariectomized (OVX) under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia. Rats were injected sc with estradiol benzoate (E; 2 μg/0.1 mL safflower oil) at 10.00 hr on days 14 and 17, and progesterone (P; 2.0 mg/0.2 mL safflower oil) at 11.00 hr on day 18 [Singh and Briski, 2004]. Continuous intra-CV4 infusion of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; groups 1 and 2) or aCSF containing L-lactate (25μM/2.0μL/hr [Patil and Briski, 2005]; group 3) was performed between 13.50 and 16.00 hr on day 18, using 33-gauge 0.5 mm-projecting internal injection cannulas (prod. no. C315I/SPC; Plastics One). At 14.00 hr, rats in group 1 received a sc injection of sterile vehicle (V; Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN; n=5), while animals in groups 2 and 3 were injected with neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin (I; 12.5 U/kg bw [Paranjape and Briski, 2005]; Henry Schein, Butler, OH; n=6 per group). Animals were sacrificed by decapitation at +120 min (16.00 hr) for brain and blood collection. Previous studies in our laboratory indicate that this is an optimal time frame for substrate fuel deficit inhibition of the LH surge [Singh and Briski, 2004; Ibrahim and Briski, 2014]. Dissected brains were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane and stored at −80°C. Plasma was obtained by immediate centrifugation and stored at −20°C.

Plasma Glucose and LH measurements

Glucose levels were measured with an Accuchek Advantage glucometer (product no. 860; Roche Diagnostic Corporation, Indianapolis) [Kale et al., 2006]. LH was measured by radioimmunoassay [Singh and Briski, 2004].

Laser-catapult Microdissection of Hindbrain A2 Noradrenergic and Rostral Preoptic GnRH Neurons for Western Blot Protein Analysis

Fresh-frozen 10 μm serial sections were cut from each hindbrain at rostro-caudal levels corresponding to the location of A2 neurons (-14.30 to-14.60 mm; Paxinos and Watson, 1998), mounted on polyethylene naphthalate membrane slides, and labeled for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-immunoreactivity (-ir) by avidin-biotin peroxidase immunochemistry [Briski et al., 2009]. Serial sections through the forebrain preoptic area were cut between +0.40 to −0.40 mm; rostral preoptic GnRH neurons were immunolabeled using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against GnRH-I (Ibrahim and Briski, 2014). This subpopulation of GnRH cells was targeted for analysis as it is characterized by transcriptional reactivity to glucoprivation [Briski and Sylvester, 1998; Singh and Briski, 2004]. TH-ir A2 and GnRH-ir neurons were individually circumdissected from tissue sections using a Zeiss P.A.L.M. UV microlaser (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging; Thornwood, NY). For each protein of interest, n=50 neurons (n=8-10 cells per rat) were pooled per treatment group. Denatured nerve cell lysates were separated on Tris-glycine gels and transferred to 0.45 um PVDF-Plus membranes. Membranes were treated with Pierce Western blot signal enhancer and blocked with 0.1% Tween-20 and 2% bovine serum albumin prior to sequential incubation with primary antisera, peroxidase-conjugated secondary antiserum, and Supersignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity substrate. A2 cell lysates were probed for Fos, AMPKα1/2 (AMPK), phosphoAMPKα1/2 (pAMPK), DβH, ERα, ERβ, progesterone receptor (PR), monocarboxylate transporter-2 (MCT2), glucose transporter-3 (GLUT3), glucose transporter-4 (GLUT4), and α-tubulin protein expression [Cherian and Briski, 2012; Ibrahim et al., 2014]. GnRH neurons were analyzed for pAMPK, GnRH-I, and α-tubulin proteins [Ibrahim et al., 2014]. Chemiluminescent signals were visualized in a Syngene G:box Chemi; protein band optical densities (O.D.) were quantified with Syngene Genetool 4.01 software, and expressed relative to α-tubulin. Protein molecular weight markers were included in each Western blot analysis. Immunoblot analyses were performed at a minimum in triplicate.

Statistical Analyses

Mean glucose, LH, and normalized A2 and GnRH nerve cell Western blot O.D. values were evaluated by one-way ANOVA and Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test. Differences of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Effects of sc insulin (I) injection on plasma glucose and LH concentrations in steroid-primed OVX female rats: Impact of caudal fourth ventricular lactate infusion

Circulating glucose levels were significantly decreased in I-injected groups [I/artificial cerebrospinal fluid-infused (aCSF); 65.2 ± 2.4 mg/dL versus I/lactate-infused (I/lactate); 62.2 ± 2.9 mg/dL] relative to vehicle-injected, aCSF-infused controls (V/aCSF; 146.8 ± 4.96 mg/dL) [F2,13 = 179.92; p < 0.0001]. The magnitude of glucose reduction was equivalent in I/aCSF versus I/lactate groups. Plasma LH levels were diminished by hypoglycemia [V/aCSF; 3.5 ± 0.4 ng/mL versus I/aCSF; 1.5 + 0.2 ng/mL; F2,12 = 16.43; p = 0.0005]. Hormone secretion was normalized by combined I plus lactate treatment [V/aCSF; 3.5 ± 0.4 ng/mL versus I/lactate; 3.0 ± 0.3 ng/mL].

Effects of hypoglycemia, with or without caudal hindbrain lactate infusion, on A2 nerve cell protein expression during steroid positive-feedback activation of the reproductive neuroendocrine axis

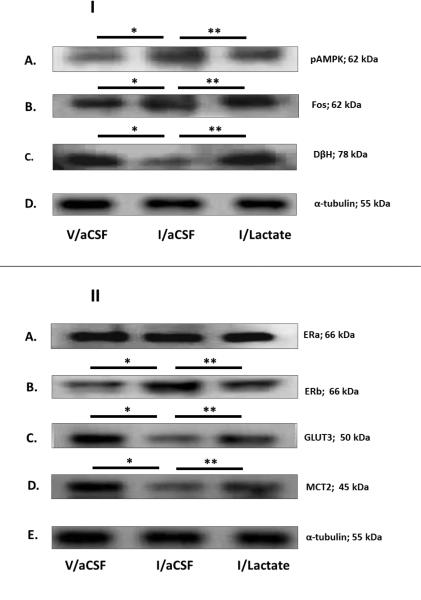

Caudal dorsal vagal complex A2 neurons identified by TH-immunostaining were individually laser-microdissected 2 hr after V or I injection to steroid-primed OVX female rats. Figure 1.I depicts representative immunoblots of pAMPK [Row A], Fos [Row B], and DβH [Row C] proteins, with corresponding levels of the housekeeping protein, α-tubulin [Row D], in A2 neurons from V/aCSF- [left-hand column], I/aCSF- [middle column], and I/lactate- [right-hand column] treated animals. Mean normalized O.D. measures presented in Figure 2 indicate that hypoglycemia had no impact on A2 AMPK protein expression [F2,7 = 2.96; p = 0.1278], but significantly increased pAMPK [Figure 2.B; F2,13 = 5.10; p = 0.0249] and Fos [Figure 2.C; F2,10 = 9.3825; p = 0.0063] profiles, while decreasing DβH [Figure 2.D; F2,13 = 15.353; p = 0.0005] protein. Hindbrain lactate infusion reversed effects of hypoglycemia on pAMPK, Fos, and DβH protein levels. Figure 1.II shows representative Western blots of A2 ERα [Row A], ERβ [Row B], GLUT3 [Row C], MCT2 [Row D], and α-tubulin [Row E] protein expression in V/aCSF, I/aCSF, and I/lactate treatment groups. Quantitative data depicted in Figures 2.E and 2.F illustrate absent [F2,7 = 0.03; p = 0.9697] or stimulatory [F2,7 = 14.9336; p = 0.276] effects, respectively, of hypoglycemia on ER and ER protein profiles; A2 ERβ expression was normalized by lactate infusion during hypoglycemia. Figure 2.G shows that hypoglycemic augmentation of A2 nerve cell progesterone receptor (PR) protein levels [F2,13 = 9.1822; p = 0.0038] was not further modified by hindbrain lactate repletion. Figures 2.H, 2.I, and 2.J depict effects of hypoglycemia, with or without lactate infusion to the caudal hindbrain, on A2 GLUT3, GLUT4, and MCT2 protein content. Data show that hypoglycemic repression of GLUT3 [F2,7 = 6.5823; p = 0.0307] and MCT2 [F2,13 = 6.3181; p = 0.0134] proteins was reversed by lactate. GLUT4 protein profiles were not modified by treatment with I alone or in combination with lactate [F2,7 = 1.1766; p = 0.4195].

Figure 1. Effects of Hypoglycemia on Hindbrain Dorsal Vagal Complex A2 Noradrenergic Nerve Cell Phospho-Adenosine 5’-Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase (pAMPK), Fos, Dopamine-β-Hydroxylase (DH), Steroid Hormone Receptor, and Substrate Fuel Transporter Protein Expression in Steroid-Primed Ovariectomized (OVX) Female Rats: Impact of Caudal Fourth Ventricular L-Lactate Infusion.

Individual tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-immunoreactive (-ir) A2 neurons were laser-microdissected from 10 μm-thick sections of the caudal dorsal vagal complex of steroid-primed OVX animals 2 hr after sc injection of vehicle (V; group 1; n=5) or neutral protamine Hagedorn Insulin (I; 12.5 U/kg bw; groups 2 and 3; n=6/group). Animals were continuously infused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; groups 1 and 2) or aCSF containing L-lactate (25μM/2.0μL/hr; group 3) into the caudal fourth ventricle between −10 and +120 min after injections. For each protein of interest, separate lysates of pooled n=50 A2 cells (n=8-10/rat) were analyzed by Western blot in triplicate at minimum. Figure 1.I depicts representative immunoblots of A2 phosphoAMPK (Row A), Fos (Row B), DβH (Row C); and α-tubulin (Row D) for each treatment group. Figure 1.II shows typical Western blots of A2 estrogen receptor-alpha (ER ; Row A), estrogen receptor-beta (ER ; Row B), glucose transporter-3 (GLUT3; Row C), monocarboxylate transporter-2 (MCT2; Row D), and α-tubulin (Row E). *p < 0.05, versus V/aCSF; **p < 0.05, versus I/aCSF; these symbols denote outcomes of statistical analyses shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Effects of Hindbrain Lactate Repletion on Normalized A2 Nerve Cell Protein Expression in Hypoglycemic Steroid-Primed OVX Animals.

Protein band optical densities (O.D.) of immunoblots of n=50 A2 neurons/treatment group from V/aCSF- (white bars), I/aCSF- (gray bars), and I/Lactate (diagonal-striped gray bars) - treated rats were quantified with Syngene Genetool 4.01 software and expressed relative to α-tubulin. Panels depict mean normalized O.D. values ± S.E.M. for A2 nerve cell AMPK (Figure 2.A), pAMPK (Figure 2.B), Fos (Figure 2.C), DβH (Figure 2.D), ER (Figure 2.E), ERβ (Figure 2.F), progesterone receptor (PR; Figure 2.G), GLUT3 (Figure 2.H), glucose transporter-4 (GLUT4; Figure 2.I), and MCT2 (Figure 2.J) protein levels 2 hr after sc injections. *p < 0.05, versus V/aCSF; **p < 0.05, versus I/aCSF.

Effects of hypoglycemia, with or without caudal hindbrain lactate infusion, on rostral preopptic GnRH neuron protein expression during steroid positive-feedback activation of the reproductive neuroendocrine axis

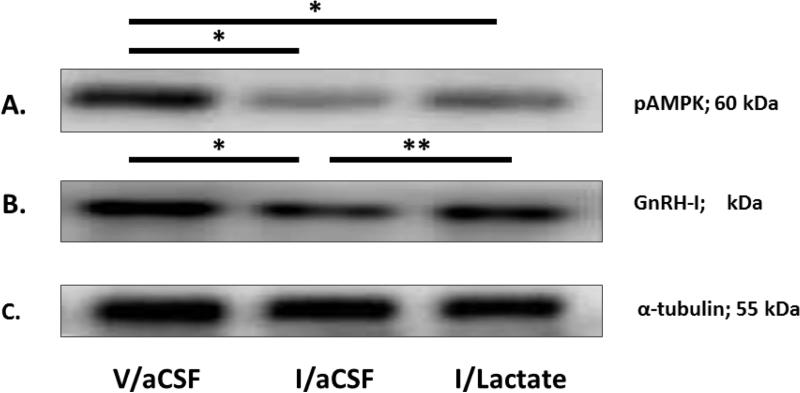

Figure 3 depicts representative immunoblots of pAMPK [Row A], GnRH-I [Row B], and α-tubulin [Row C] proteins in GnRH neurons from V/aCSF- [left-hand column], I/aCSF- [middle column], and I/lactate- [right-hand column] treated steroid-primed OVX female rats. Mean normalized O.D. measures presented in Figure 4 reveal that hypoglycemia decreased GnRH nerve cell pAMPK [Figure 4.A; F2,13 = 22.5431; p < 0.0001] and GnRH-I [Figure 2.B; F2,13 = 38.6594; p < 0.0001] protein expression; hindbrain lactate infusion reversed the latter, but not the former inhibitory response.

Figure 3. Effects of Hypoglycemia on Rostral Preoptic Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) pAMPK and GnRH-I Protein Expression in Steroid-Primed OVX Female Rats: Impact of Caudal Fourth Ventricular L-Lactate Infusion.

Individual GnRH-ir neurons were laser-microdissected from sections of the rostral preoptic area of steroid-primed OVX animals 2 hr after sc injection of V (group 1) or I (groups 2 and 3). Animals were continuously infused with aCSF (groups 1 and 2) or aCSF containing L-lactate (25μM/2.0μL/hr; group 3) into the caudal fourth ventricle between −10 and +120 min after injections. For each protein of interest, separate lysates of pooled n=50 GnRH neurons (n=8-10/rat) were analyzed by Western blot in triplicate at minimum. Figure 1.I depicts representative immunoblots of GnRH phosphoAMPK (Row A), GnRH-I (Row B), and α-tubulin (Row C). *p < 0.05, versus V/aCSF; **p < 0.05, versus I/aCSF; these symbols denote outcomes of statistical analyses shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Effects of Hindbrain Lactate Repletion on Normalized GnRH Nerve Cell Protein Expression in Hypoglycemic Steroid-Primed OVX Rats.

Protein band optical densities (O.D.) of immunoblots of n=50 GnRH neurons/treatment group from V/aCSF- (white bars), I/aCSF- (gray bars), and I/Lactate (diagonal-striped gray bars) - treated rats were quantified with Syngene Genetool 4.01 software and expressed relative to α-tubulin. Panels depict mean normalized O.D. values ± S.E.M. for GnRH nerve cell pAMPK (Figure 2.A) and GnRH-I (Figure 2.B) protein content 2 hr after treatments. *p < 0.05, versus V/aCSF; **p < 0.05, versus I/aCSF

Discussion

Recent studies support the function of hindbrain A2 noradrenergic neurons as a common pathway for opposing steroidal stimulatory versus metabolic inhibitory input to the GnRH-pituitary LH axis [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014]. This novel notion presumes that these cells control the LH surge according to prevailing energy status, acting to inhibit this key reproductive event in response to acute reductions in substrate fuel-derived energy. The present studies demonstrate that hypoglycemia attenuates steroid positive-feedback activation of the reproductive neuroendocrine system through mechanisms involving under-supply of the glucose metabolite lactate to the caudal hindbrain. Our previous work supports A2 nerve cell involvement in LH surge suppression by pharmacological induction of hindbrain glucopenia [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014]. Present data show that exogenous lactate infusion to the caudal hindbrain of hypoglycemic steroid-primed OVX female rats normalized A2 nerve cell AMPK activity and DβH, Fos, and membrane glucose and monocarboxylate transporter protein profiles, while simultaneously reversing inhibitory effects of hypoglycemia on rostral preoptic GnRH neuron GnRH-I neuropeptide levels and pituitary LH secretion. Notably, hypoglycemic repression of GnRH pAMPK expression was unaffected by hindbrain lactate replenishment. These results imply that hindbrain lack of lactate during hypoglycemia mediates adjustments in A2 signaling that inhibit the LH surge. Evidence for discordant effects of hypoglycemia on GnRH AMPK activity and pituitary LH release, along with refractoriness of this sensor to hindbrain lactate status suggests that GnRH AMPK is uninvolved in regulation of GnRH neurotransmission during in vivo glucopenia.

The current research shows that induction of hypoglycemia at the onset of the steroid positive-feedback - induced LH surge increased A2 nerve cell pAMPK, Fos, and ERβ protein profiles, while inhibiting expression of the catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme DβH. This outcome differs from our previous findings that hypoglycemia reduces A2 AMPK activity in OVX female rats given estradiol replacement at levels that impose negative feedback [Cherian and Briski, 2012]. This discrepancy may reflect, in part, differential effects of estradiol positive- and negative-feedback signaling (mediated by estrous cycle-peak versus -nadir plasma steroid levels, respectively) on levels of lactate available to neurons and/or A2 neuron AMPK reactivity to AMP/ATP imbalance or regulation by upstream kinases. Previously, we found that glucose anti-metabolite 5-thioglucose (5TG) delivery to caudal hindbrain prior to the LH surge diminished A2 pAMPK expression, while suppressing A2 DβH protein profiles and pituitary LH release [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014]. Taken together, this and our previous study show that A2 AMPK activation and deactivation correlate with hypo- versus glucose anti-metabolite-associated hyperglycemia, respectively, in the presence of estrogen positive-feedback. Evidence for reduced A2 pAMPK expression after 5TG treatment implies the operation, between to and +2 hr, of counteractive mechanisms that promote positive cell energy balance despite pharmacological suppression of glycolysis. Decreased sensor activity at this post-injection time point was likely preceded by drug-induced pAMPK augmentation, an outcome that would be expected to trigger compensatory adjustments in energy production and/or expenditure. Hypoglycemia and pharmacological shut-down of glycolysis may result in dissimilar magnitudes of glycolytic end-product shortage, e.g. lactate provision may be more severely limited under the latter condition and thus elicit relatively amplified corrective changes. Conversely, decreased A2 AMPK activity in 5TG-treated animals may not reflect positive energy balance, but rather effects of neurochemical or hormonal correlates of hyperglycemia on this enzyme, independent of cellular energy deficiency. There remains a critical need to develop analytical methods of requisite sensitivity for measurement of AMP/ATP levels in single neurons in vivo; such techniques would provide critical insight on energetic adaptation of A2 cells to metabolic stress.

A2 DβH protein expression is down-regulated by both hypoglycemia (current data) and hindbrain 5TG administration [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014]; here, lactate reversal of this negative protein response implies that hypoglycemia-associated lactate shortfall inhibits A2 neurotransmission. Systemic glucose anti-metabolite injection is reported to stimulate A2 DβH gene expression [Li et al., 2006]; this inconsistency could reflect, in part, 1) sex or more specifically, estrogen-dependent differences in A2 reactivity to lactate deficiency and/or 2) divergent effects of lactate shortfall on DβH protein versus mRNA expression. Present outcomes disclose contrary effects of hypoglycemia, alone or paired with lactate repletion, on A2 DβH and Fos protein profiles; expression of this transcriptional factor was similarly enhanced by hindbrain 5TG treatment [Ibahim and Briski, 2014]. Hypoglycemic augmentation of A2 genomic activity, denoted by Fos protein up-regulation, alongside decreased catecholamine transmitter synthesis may reflect metabolic functional adaptations designed to counteract lactate under-supply and/or to divert energy to activities unassociated with synaptic firing. Estrogen positive-feedback up-regulates A2 TH gene expression and Fos immunolabeling [Jennes et al., 1992; Curran-Rauhut and Petersen, 2004]. ERα is implicated in positive-feedback induction of the LH surge as that event is abolished by ER knockdown [Wintermantel et al., 2006; Christian et al., 2008]. A2 neurons are likely substrates for estrogen feedback as these cells express ERα and -β mRNAs and proteins [Ibrahim et al., 2013; Tamrakar et al., 2015]. Hypoglycemia stimulates A2 ERβ and PR proteins; lactate infusion normalized the former, but not latter profile, suggesting that ERβ and PR proteins correspondingly respond to local versus extra-hindbrain sequelae of hypoglycemia. It would be informative to learn if augmented ERβ-mediated input to A2 cells elicits 1) hypoglycemic repression of steroid positive-feedback - induced neurotransmission and/or 2) adaptive cellular responses to energetic instability due to diminished lactate. Both hypoglycemia and hindbrain pharmacological glucoprivation augment A2 ER protein, but exert opposite effects on ERα and PR profiles, data that argue against a role for the latter two receptors in comparable A2 nerve cell DβH/Fos protein and pituitary LH secretory responses in the two distinct experimental models. Further research is needed to investigate the role of AMPK in lactoprivic-mediated adjustments in DβH, Fos, and ERβ protein expression in steroid positive-feedback activated A2 neurons.

Hypoglycemia suppressed, whereas combinatory insulin and lactate treatment normalized A2 neuron GLUT3 and MCT2 protein profiles; these data suggest that transport mechanisms for lactate and glucose uptake into steroid-activated A2 cells may be up- or down-regulated in accordance with lactate surfeit versus shortfall. The present data confirm our prior research demonstrating reversal of hypoglycemic reductions in MCT2 mRNA by caudal hindbrain lactate infusion in male rats [Patil and Briski, 2005], and bolster the view that MCT2 transporter expression likely parallels extracellular lactate concentrations, with lactate uptake being proportionate to availability. As hyperglycemia occurs in response to inhibition of caudal hindbrain lactate transport [Patil and Briski, 2005], we presume that absolute reductions in lactate uptake by A2 neurons, independent of glucose transport, may be a key metabolic event that triggers metabolic deficit signaling by these cells. We previously reported that A2 GLUT3 and MCT2 proteins are augmented by hypoglycemia in OVX female rats replaced with negative-feedback levels of estradiol, coincident with decreased cellular pAMPK expression [Cherian and Briski, 2012]. One explanation for discrepant effects of hypoglycemia on A2 MCT2 expression during steroid positive- versus negative-feedback is that that lactate provision to A2 neurons at +2 hr after induction of hypoglycemia may be relatively diminished during positive-feedback, as heightened noradrenergic signaling may deplete glycogen reserves of lactate equivalents over the time span between insulin injection and cell sampling. This presumption will require experimental verification that hypoglycemia results in dissimilar rates of lactate provision to A2 neurons during estrogen positive- versus negative-feedback due to differential activation state of these cells.

Our previous studies showed that rostral preoptic GnRH neurons express AMPK and pAMPK proteins in vivo, and that 5TG delivery to the hindbrain of steroid-primed OVX rats reduced sensor activity alongside decreased pituitary LH secretion [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014]. Current data show that GnRH pAMPK expression is also repressed during hypoglycemia, but that this response is not further modified by hindbrain lactate repletion. Parallel deactivation of GnRH AMPK after experimental manipulations that result in hyper- and hypoglycemia rules out a primary role for blood glucose regulation of this sensor, while refractoriness to hindbrain lactate repletion implies that sensor shut-down during hypoglycemia does not involve hindbrain input. Further studies are needed to identify local mechanisms that regulate GnRH AMPK activity during neuro-glucopenia, and to determine if diminished activity of this sensor denotes compensatory gain in positive energy balance and/or effects of neurochemical or hormonal signals on AMPK. GnRH-I precursor protein levels in GnRH neurons are decreased by hypoglycemia (present data; this inhibitory response is reversed by hindbrain lactate replenishment), but increased during hindbrain 5TG glucoprivation and associated hyperglycemia [Ibrahim and Briski, 2014]. We speculate that rate of synthesis of this neuropeptide precursor may be corresponding inhibited or elevated by hypo- and hyperglycemia, respectively, without involvement of GnRH AMPK. In light of previous evidence that the LH surge is inhibited despite augmented GnRH-I production in 5TG-treated rats, we now suspect that hindbrain metabolic signaling may counteract that event through mechanisms that inhibit yield or release of the GnRH decapeptide transmitter. The current evidence for discordant effects of hypoglycemia on GnRH metabolic sensor activity and pituitary LH release, and for GnRH AMPK insensitivity to hindbrain lactate status does implicate this sensor in regulation of GnRH neurotransmission during in vivo glucopenia. These findings from whole-animal models provide an important physiological counterpoint to in vitro evidence for AMPK involvement in GnRH nerve cell firing in brain slice preparations [Roland and Moenter, 2011]. Nonetheless, it remains of great interest to discover how GnRH AMPK deactivation impacts cell function, particularly adaptation to glucopenia.

In summary, this research demonstrates that hypoglycemia attenuates steroid positive-feedback activation of reproductive neuroendocrine axis via caudal hindbrain detection and signaling of under-supply of the glucose metabolite lactate. Western blot analyses of laser-microdissected hindbrain metabolic-sensory A2 neurons show that hypoglycemia-associated lactoprivation regulates protein markers of A2 cell function, including pAMPK, DβH, and Fos. Results also disclose that hindbrain lactate repletion does not reverse hypoglycemia-associated deactivation of GnRH nerve cell AMPK activity, but does normalize GnRH-I protein expression and pituitary LH secretion. Collectively, these findings reiterate the critical significance of functional connectivity of the hindbrain and preoptic area in metabolic repression of the LH surge. Furthermore, this study does not support involvement of GnRH AMPK in regulation of GnRH signaling to the anterior pituitary during neuro-glucopenia.

Highlights.

The luteinizing hormone (LH) surge is repressed by caudal hindbrain metabolic signaling

Insulin plus hindbrain lactate infusion normalizes positive-feedback - -induced LH secretion

Lactate reverses hypoglycemic effects on markers of A2 nerve cell function

Lactate status regulates A2 MCT2 and GLUT3 substrate fuel transporter expression

Lactate regulates GnRH neuron neuropeptide synthesis, but not AMPK activity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adam CL, Findlay PA. (Inhibition of luteinizing hormone secretion and expression of c-fos and corticotrophin-releasing factor genes in the paraventricular nucleus during insulin-induced hypoglycaemia in sheep. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1998;10:777–783. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros LF. (Metabolic signaling by lactate in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briski KP, Koshy Cherian A, Genabai NK, Vavaiya KV. (In situ coexpression of glucose and monocarboxylate transporter mRNAs in metabolic-sensitive dorsal vagal complex catecholaminergic neurons: transcriptional reactivity to insulin-induced hypoglycemia (IIH) and caudal hindbrain glucose or lactate repletion during IIH. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1152–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briski KP, Sylvester PW. (Effects of the glucose antimetabolite, 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), on the LH surge and Fos expression by preoptic GnRH neurons in ovariectomized, steroid-primed rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1998;10:769–776. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagampang FR, Cates PS, Sandhu S, Strutton PH, McGarvey C, Coen CW, O'Byrne KT. (Hypoglycaemia-induced inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in female rats: role of oestradiol, endogenous opioids and the adrenal medulla. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:867–872. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates PS, Li XF, O'Byrne KT. (The influence of 17beta-oestradiol on corticotrophin-releasing hormone induced suppression of luteinising hormone pulses and the role of CRH in hypoglycaemic stress-induced suppression of pulsatile LH secretion in the female rat. Stress. 2004;7:113–118. doi: 10.1080/1025389042000218988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MD, O'Byrne KT, Chiappini SE, Hotchkiss J, Knobil E. (Hypoglycemia ‘stress’ and gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator activity in the rhesus monkey: role of the ovary. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;56:666–673. doi: 10.1159/000126291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XB, Wen JP, Yang J, Yang Y, Ning G, Li XY. (GnRH secretion is inhibited by adiponectin through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Endocrine Feb. 2011;39:6–12. doi: 10.1007/s12020-010-9375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian A, Briski KP. (Quantitative RT PCR and immunoblot analyses reveal acclimated A2 noradrenergic neuron substrate fuel transporter, glucokinase, phospho-AMPK, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase responses to hypoglycemia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2011;89:1114–1124. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian A, Briski KP. (A2 noradrenergic nerve cell metabolic transducer and nutrient transporter adaptation to hypoglycemia: Impact of estrogen. J. Neurosci. Res. 2012;90:1347–1358. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke IJ, Horton RJE, Doughton BW. (Investigation of the mechanism by which insulin-induced hypoglycemia decreases luteinizing hormone secretion in ovariectomized ewes. Endocrinology. 1990;127:1470–1476. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-3-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CA, Glidewell-Kenney C, Jameson JL, Moenter SM. (Classical estrogen receptor alpha signaling mediates negative and positive feedback on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5328–5334. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyral-Castel S, Tosca L, Ferreira G, Jeanpierre E, Rame C, Lomet D, Caraty A, Monget P, Chabrolle C, Dupont J. (The effect of AMP-activated kinase activation on gonadotrophin-releasing hormone secretion in GT1-7 cells and its potential role in hypothalamic regulation of the oestrous cyclicity in rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosignani PG. (Nutrition and reproduction in women. The ESHRE Capri Workshop. Human Reproduction Update. 2006;12:193–207. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmk003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran-Rauhut MA, Petersen SL. (Oestradiol-dependent and -independent modulation of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels in subpopulations of A1 and A2 neurones with oestrogen receptor (ER) and ER gene expression. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:296–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demling J, Fuchs E, Baumert M, Wuttke W. (Preoptic catecholamine, GABA, and glutamate release in ovariectomised and ovariectomised estogen-primed rats utilising a push-pull cannula technique. Neuroendocrinology. 1985;41:212–218. doi: 10.1159/000124180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubillon ML, Thalabard JC. (Insulin-induced hypoglycemia decreases luteinizing hormone secretion in the castrated male rat: involvement of opiate peptides. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;64:49–56. doi: 10.1159/000127097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujar AD, Ibrahim BA, Tamrakar P, Koshy Cherian A, Briski KP. (Hindbrain lactostasis regulates hypothalamic AMPK activity and hypothalamic metabolic neurotransmitter mRNA and protein responses to hypoglycemia. Amer. J. Physiol. Regul. Integ. Comp. Physiol. 2014;306:R457–R469. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00151.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D, Funabashi T, Sano A, Uemura T, Minaguchi H, Kimura F. (Effects of glucose and related substrates on the recovery of the electrical activity of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator which is decreased by insulin-induced hypoglycemia in the estrogen-primed ovariectomized rat. Brain Res. 1999;820:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01358-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler LE, Pallotta CM, Reid RL, Van Vugt DA. (Hypoglycemia-induced inhibition of luteinizing hormone secretion in the rhesus monkey is not mediated by endogenous opioid peptides. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993;76:1280–1285. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.5.8388404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim BA, Briski KP. (Role of dorsal vagal complex A2 noradrenergic neurons in hindbrain glucoprivic inhibition of the luteinizing hormone surge in the steroid-primed ovariectomized female rat: Effects of 5-thioglucose on A2 functional biomarker and AMPK activity. Neuroscience. 2014;269:199–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim BA, Tamrakar P, Gujar AD, Koshy Cherian A, Briski KP. (Caudal fourth ventricular AICAR regulates glucose and counterregulatory hormone profiles, dorsal vagal complex metabolo-sensory neuron function, and hypothalamic Fos expression. J. Neurosci. Res. 2013;91:1226–1238. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennes L, Jennes ME, Purvis C, Nees M. (c-fos expression in noradrenergic A2 neurons of the rat during the estrous cycle and after steroid hormone treatments. Brain Res. 1992;586:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91391-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale AY, Paranjape SA, Briski KP. (I.c.v. administration of the nonsteroidal glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, CP4-72555, prevents exacerbated hypoglycemia during repeated insulin administration. Neuroscience. 2006;140:555–565. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lado-Abeal J, Clapper JA, Chen Zhu B, Hough CM, Syapin PJ, Norman RL. (Hypoglycemia-induced suppression of luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion in intact female rhesus macaques: role of vasopressin and endogenous opioids. Stress. 2002;5:113–119. doi: 10.1080/10253890290027886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laming PR, Kimelberg H, Robinson S, Salm A, Hawrylak N, Muller C, Roots B, Ng K. (Neuronalglial interactions and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000;24:295–340. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AJ, Wang Q, Ritter S. (Differential responsiveness of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase gene expression to glucoprivation in different catecholamine cell groups. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3428–3434. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharjan S, Serova L, Sabban EL. (Transcriptional regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase by estrogen: opposite effects with estrogen receptors alpha and beta and interactions with cyclic AMP. J Neurochem. 2005;93:1502–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina CL, Nagatani S, Darling TA, Bucholtz DC, Tsukamura H, Maeda K, Foster DL. (Glucose availability modulates the timing of the luteinizing hormone surge in the ewe. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1998;10:785–792. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohankumar PS, Thyagarajan S, Quadri SK. (Correlations of catecholamine release in the medial preoptic area with proestrous surge. Endocrinology. 1994;135:119–126. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.1.8013343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura S, Tanaka T, Nagatani S, Bucholtz DC, Tsukamura H, Maeda K, Foster DL. (Central, but not peripheral, glucose-sensing mechanisms mediate glucoprivic suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in the sheep. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4472–4480. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns KM, Fruehwald-Schultes B, Kern W, Born J, Fehm HL, Peters A. (Hypoglycemia, but not insulin, acutely decreases LH and T secretion in men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:4913–4919. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjape SA, Briski KP. (Recurrent insulin-induced hypoglycemia causes site-specific patterns of habituation or amplification of CNS neuronal genomic activation. Neuroscience. 2005;130:957–970. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil GD, Briski KP. (Lactate is a critical ‘sensed’ variable in caudal hindbrain monitoring of CNS metabolic stasis. Amer. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005;289:R1777–R1786. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00177.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ. (Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis: a mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1994;91:10625–10629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin L, Pellegri G, Bittar PG, Charnay Y, Bouras C, Martin JL. (Evidence supporting the existence of an activity-dependent astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle. Dev. Neurosci. 1998;20:291–299. doi: 10.1159/000017324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland AV, Moenter SM. (Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by glucose. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;22:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter LM, Manns JG. (Hypoglycemia alters pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in the postpartum beef cow. J. Anim. Sci. 1987;64:479–488. doi: 10.2527/jas1987.642479x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha PK, Tamrakar P, Ibrahim BA, Briski KP. Hindbrain medulla catecholamine cell group involvement in lactate-sensitive hypoglycemia-associated patterns of hypothalamic norepinephrine and epinephrine activity. Neuroscience. 2014;278:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver IA, Ereci ska M. (Glucose-induced intracellular ion changes in sugar-sensitive hypothalamic neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1733–1745. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SR, Briski KP. (Septopreoptic mu opioid receptor mediation of hindbrain glucoprivic inhibition of reproductive neuroendocrine function in the female rat. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5322–5331. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szawka RE, Poletini MO, Leite CM, Bernuci MP, Kalil BK, Mendonca LBD, Carolino ROG, Helena CVV, Bertram R, Franci CR, Anselmo-Franci JA. (Release of norepinephrine in the preoptic area activates anteroventral periventricular nucleus neurons and stimulates the surge of luteinizing hormone. Endocrinology. 2013;154:363–374. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamrakar P, Ibrahim BA, Gujar AD, Briski KP. (Estrogen regulates energy metabolic pathway and upstream adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase and phosphatase enzyme expression in dorsal vagal complex metabolosensory neurons during glucostasis and hypoglycemia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2015;93:321–332. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen JP, Lu WS, Yang J, Nie AF, Cheng XB, Yang Y, Ge Y, Li XY, Ning G. (Globular adiponectin inhibits GnRH secretion from GT1-7 hypothalamic GnRH neurons by induction of hyperpolarization of membrane potential. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;371:756–761. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermantel TM, Campbell RE, Porteous R, Bock D, Gröne HJ, Todman MG, Korach KS, Greiner E, Pérez CA, Schülz G, Herbison AE. Definition of estrogen receptor pathway critical for estrogen positive feedback to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and fertility. Neuron. 2006;52:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss MT, Jolivet R, Buck A, Magistretti PJ, Weber B. (In vivo evidence for lactate as a neuronal energy source. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:7477–7485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0415-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Bosch M, Levine JE, Ronnekleiv O, Kelly M. (GnRH neurons express KATP channels that are regulated by estrogen and responsive to glucose and metabolic inhibition. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10153–10164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1657-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]