Abstract

Mechanically-induced skeletal muscle growth is regulated by mTORC1. YAP is a mechanically-sensitive, and growth-related, transcriptional co-activator that can regulate mTORC1. Here we show that, in skeletal muscle, mechanical overload promotes an increase in YAP expression; however, the time course of YAP expression is markedly different from that of mTORC1 activation. We also show that the overexpression of YAP induces hypertrophy via an mTORC1-independent mechanism. Finally, we provide preliminary evidence of possible mediators of YAP-induced hypertrophy (e.g. increased MyoD and c-Myc expression, and decreased Smad2/3 activity and MuRF1 expression).

Keywords: mTORC1, mechanotransduction, YAP, synergist ablation, Hippo pathway, TEAD

INTRODUCTION

The Yes-Associated Protein (YAP) is a cell growth-related transcriptional co-activator that is, in part, regulated by the Hippo signaling network [1]. More specifically, YAP can be phosphorylated by the large tumor suppressor kinases 1 and 2 (LATS1/2) which serve as the terminal kinases of the Hippo pathway. The phosphorylation of YAP on the serine 112 residue (S112; S127 in humans) by LATS1/2 leads to its exclusion from the nucleus, and thus, a reduction in its activity as a transcriptional co-activator [2]. In its active form, YAP binds and co-activates a range of transcription factors including the TEA domain (TEAD) transcription factors [3]. Active TEAD transcription factors can, in turn, regulate the expression of genes in various tissues by binding to promoters that contain MCAT (muscle C, A, and T) and A/T-rich sites [4,5]. Thus, YAP has the potential to regulate cell growth-related gene expression and signaling in multiple cell types.

YAP has recently been implicated in the transduction of mechanical signals (i.e., mechanotransduction) that regulate various processes including cellular growth (for review see [6]). For instance, it was recently shown that mechanical stretch-induced increases in cell proliferation are associated with an in increase the amount of nuclear YAP [7]. Moreover, recent studies have found that YAP not only regulates proliferation, but it can also regulate cell size by increasing the activity of the mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) [8]. The effects of YAP on mTORC1 are particularly intriguing because signaling by mTORC1 has also been widely implicated in the mechanical regulation of skeletal muscle growth [9]. For instance, subjecting muscles to chronic mechanical overload results in an mTORC1-dependent increase in muscle fiber size (i.e., hypertrophy) [9,10]. Thus, based on the studies which have shown that YAP is sensitive to changes in mechanical loading, and that YAP can regulate mTORC1 signaling, we reasoned that YAP might play a role in the mechanical activation of mTORC1 and skeletal muscle growth. Therefore, the goal of this study was to explore these possibilities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Extended Materials and Methods are provided in the accompanying supplementary material

Animals

Male and female FVB/N mice, 8–10 weeks old, were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water unless otherwise stated. Before all surgical proceudres, mice were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). After tissue extraction, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. All methods were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Synergist Ablation Surgery

Male mice were subjected to bilateral synergist ablation (SA) surgeries which involved removing the soleus and distal half of the gastrocnemius muscle as previously described [10-12].

Plasmid Constructs and Purification

All plasmid DNA constructs and amounts used for co-transfection in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Plasmid DNA was amplified in DH5α Escherichia coli, purified with an EndoFree plasmid kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and resuspended in sterile PBS as previously described [13,14].

In Vivo Transfection via Electroporation

Sterile plasmid DNA was transfected into Tibialis Anterior (TA) muscles of female mice by electroporation as described previously [13,14].

Rapamycin Injections

Rapamycin was purchased from LC laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA) and was dissolved in DMSO to generate a 5 μg/μl stock solution. The appropriate volume of the stock solution needed to inject mice with 1.5 mg/kg of rapamycin was dissolved in 200 μl of PBS. For the vehicle control condition, mice were injected with an equivalent amount of DMSO dissolved in 200 μl of PBS. Immediately following electroporation the vehicle or rapamycin solutions were administered via intraperitoneal injections, and these injections were repeated every 24 h for 7 days.

Western Blotting

Muscle protein samples were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis as previously described [10]. Specific antibodies that were used are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Immunohistochemical Analysis of Muscle Fiber Cross-Sectional Area

Transfected TA muscles were dissected, cut and processed for immunohistochemical staining and quantification of muscle fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) as previously described [14]. Specific antibodies used are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as means (+SEM in graphs). Student's 2-tailed unpaired t-tests were used for all 2-group comparisons. Time course data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test. Four group comparisons were performed using a two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Differences between groups were considered significant if P < 0.05. All data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Mechanical overload induces an increase in the expression of YAP

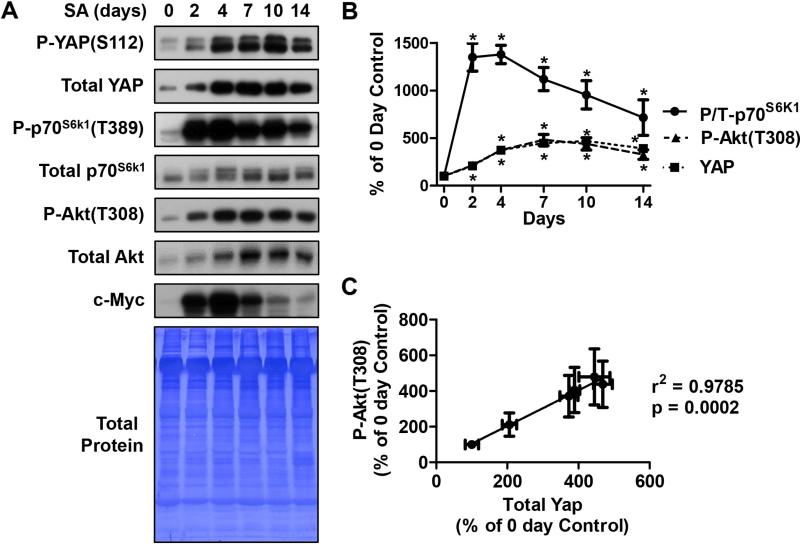

To determine whether the expression of YAP is sensitive to increased mechanical loading, we utilized the synergist ablation (SA) model [10]. SA places a chronic mechanical overload on the Plantaris muscle which results in a progressive increase in muscle mass over 10-14 days (e.g. see [12,15]). As shown in Figure 1 A and B, SA induced a progressive increase in the protein levels of total YAP protein with a peak (~4.5-fold) occurring at 7 days following the onset of SA. Similarly, Yap phosphorylation on the serine 112 residue [P-YAP(S112)] was also increased by SA but no significant change in the YAP phospho to total ratio was detected (Fig. 1A). These data show that YAP expression and the Hippo signaling pathway are both sensitive to increased mechanical loading in skeletal muscle. We next examined the effect of SA on mTORC1 signaling as measured by changes in the phosphorylation of p70S6k1 on the threonine 389 residue [P-p70S6k1(T389)]. The results from these analyses revealed that SA induced a relatively rapid increase in mTORC1 signaling that peaked at day 2 (~14-fold) and then slowly declined between days 4 and 14 (Fig. 1A and B). The different temporal effects of SA on total YAP and mTORC1 signaling indicate that there is not a simple relationship between the activation of mTORC1 and changes in total YAP expression under these conditions. This is further highlighted by our finding that the SA-induced increase in c-Myc, whose expression is known to be positively regulated by YAP [16-21], also displays a different temporal pattern to YAP and mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. The effect of synergist ablation on YAP, Akt and c-Myc, and mTORC1 signaling.

Plantaris muscles were subjected to synergist ablation (SA) and then collected either immediately (0 day) or up 14 days after the onset of SA. (A) The muscles were subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies and then the Western blot membranes were stained with Coomassie blue to verify equal loading of protein in all lanes. (B) The mean time course data for the phosphorylated to total ratio (P/T) of p70S6k1, and the amounts of phosphorylated Akt [P-Akt(T308)] and YAP. (C) Correlation between the SA-induced changes in YAP and P-Akt(T308). All values are expressed as a percentage of the mean value obtained in the control (0 day) samples and are reported as the mean + SEM, n = 3-8 / group. * Significantly different from 0 day, P ≤ 0.05.

In addition its potential role in the regulation of mTORC1 signaling, several studies have also proposed that YAP can function as an upstream regulator of Akt [8,22,23]. Therefore, we next examined the effects of SA on Akt activity as assessed by the levels of threonine 308 phosphorylated Akt [P-Akt(T308)]. Our results demonstrated that SA induces a significant increase in the amount of P-Akt(T308) and the temporal nature of this event was remarkably similar to effects of SA on YAP expression (Fig. 1). Indeed, these two events revealed a very high correlation co-efficient (r2 = 0.9785) (Fig. 1C). A similar correlation co-efficient (r2 = 0.931) was also found between the SA-induced increase in YAP expression and total Akt levels (data not shown). These strong correlations suggest that the SA-induced increase in YAP expression might play a role in a pathway through which SA regulates the expression of Akt and its overall activity.

The overexpression of YAP induces hypertrophy through an mTORC1-independent mechanism

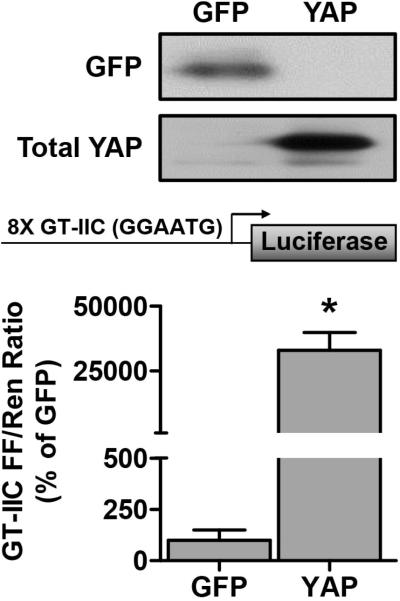

In the next series of experiments we set out to determine whether an increase in the expression of YAP would be sufficient to induce muscle fiber hypertrophy, and whether signaling through mTORC1 would be necessary for this event. To accomplish this, we used electroporation to transfect mouse TA muscles with HA-tagged YAP. As shown in Figure 2, our electroporation procedure enabled us to robustly overexpress YAP. Furthermore, we performed experiments in which TA muscles were co-transfected with YAP and a GT-IIC luciferase reporter construct that contains 8 TEAD binding motifs (GGAATG) from the simian virus 40 (SV40) enhancer [4]. As shown in Figure 2, the results from these experiments revealed that the overexpression of YAP induced a dramatic increase in the activity of the TEAD binding reporter, thus confirming that the overexpressed YAP was transcriptionally active.

Figure 2. Overexpressed YAP is transcriptionally active.

Mouse TA muscles were cotransfected with HA-tagged YAP, or GFP as a control, as well as a TEAD binding element firefly (FF) luciferase reporter containing 8 GGAATG binding motifs (GT-IIC FF), and the pRL-SV40 Renilla (Ren) luciferase reporter. At 72 hours post-transfection, the muscles were collected and FF and Ren luciferase activities were measured with a dual-luciferase assay. Measurements of the relative light units produced by FF luciferase were normalized to that produced by Ren luciferase and this ratio is expressed as a percentage of the values obtained from the GFP transfected muscles. Values are reported as the mean + SEM, n = 3-5 / group. * Significantly different from the values obtained in GFP-transfected muscles.

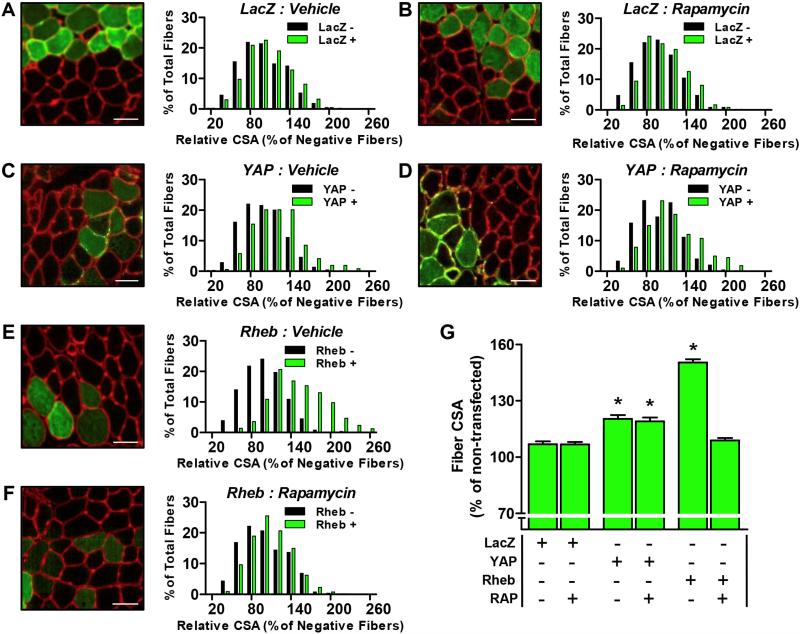

Next we transfected TA muscles with YAP, or LacZ as a control condition, and then treated the mice with daily injections of rapamycin or the solvent vehicle. After 7 days, the muscles were collected and the CSA of the transfected and non-transfected fibers were analyzed. As shown in Figure 3, the results from these analyses demonstrated that the overexpression of YAP was sufficient to induce hypertrophy (Fig. 3C and 3G). However, in contrast to our hypothesis, the hypertrophic effect of YAP was not prevented when the mice were treated with rapamycin (Fig. 3D and 3G). Therefore, to confirm the efficacy of the rapamycin treatment, we performed an additional experiment in which TA muscles were transfected with Rheb. Previous studies have shown that Rheb can directly bind and activate mTORC1 [13,24], and as shown in Figures 3E and 3G, the overexpression of Rheb induced a robust hypertrophic response. Moreover, the hypertrophic effect of Rheb was effectively abolished when the mice were treated with rapamycin (Fig. 3F and 3G). These results confirmed the effectiveness of our rapamycin treatment and provide further evidence that YAP induces hypertrophy through an mTORC1-independent mechanism.

Figure 3. The overexpression of YAP induces hypertrophy through an mTORC1-independent mechanism.

Mouse TA muscles were transfected with LacZ as a control (A, B), HA-tagged YAP (C, D) or YFP-tagged Rheb (E, F). Immediately after transfection, the mice were given daily injections of a solvent vehicle (A, C, and E) or 1.5 mg/kg rapamycin (RAP) (B, D, and F). Muscles were collected at 7 days post-transfection and subjected to immunohistochemistry for laminin (red) and LacZ, HA or YFP (green). (A-F) Representative merged images of Laminin and (A, B) LacZ, (C, D) HA-YAP, or (E, F) YFP-Rheb. The CSA of the transfected fibers and non-transfected fibers were measured and expressed relative to the mean value obtained for the non-transfected fibers in each muscle. Histograms represent the relative CSA for the transfected fibers (green bars) and non-transfected fibers (black bars) obtained in each group (n = 363-645 transfected and n = 440-645 non-transfected fibers/group). (G) The graph represents the average relative CSA of the transfected fibers that was obtained in each group. Values are reported as the mean + SEM, n = 363-645 fibers (4-5 muscles) / group. * Significantly different from the drug-matched (vehicle or RAP) LacZ transfected fibers, P ≤ 0.05. Scale bars in the images represent a length of 50 μm.

The effect of YAP on MyoD, c-Myc and MuRF1 promoter activity, and on Smad2/3 transcriptional activity

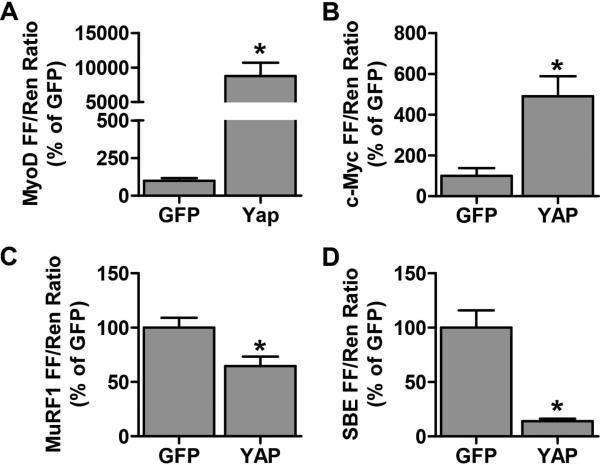

To gain further insight into the potential mechanism(s) that are responsible for the hypertrophic effect of YAP, we measured the promoter activity of various putative YAP targets that have the potential to regulate skeletal muscle mass. For example, the myogenic regulatory factor, MyoD, is a potential positive regulator of skeletal muscle mass and the MyoD promoter contains an MCAT element [25,26]. Thus, we examined whether the overexpression of YAP was sufficient to activate the MyoD promoter activity and found that this was indeed the case (Fig. 4A). Based on this observation, we propose that an increase in MyoD expression may contribute to the hypertrophic effects of YAP.

Figure 4. YAP activates the MyoD and c-Myc promoters, inhibits the MuRF1 promoter and inhibits Smad 2/3 transcriptional activity.

Mouse TA muscles were co-transfected with HA-tagged YAP, or GFP as a control, as well as the pRL-SV40 Renilla (Ren) luciferase reporter, and either the (A) MyoD (B) c-Myc or (C) MuRF1 promoter, or a (D) Smad Binding Element (SBE) firefly (FF) luciferase reporter. At 72 hours post-transfection, the muscles were collected and FF and Ren luciferase activities were measured with a dual-luciferase assay. Measurements of the relative light units produced by FF luciferase were normalized to that produced by Ren luciferase and this ratio was expressed as a percentage of the values obtained in the GFP transfected muscles. Values are reported as the mean + SEM, n = 3-4 / group. * Significantly different from the GFP-transfected muscles, P ≤ 0.05.

c-Myc is another regulator of cell growth and, as mentioned above, recent studies have shown that the expression of c-Myc is positively regulated by YAP [16-21]. Therefore, we examined whether the overexpression of YAP was sufficient to induce an increase in the activity of a c-Myc promoter construct (c-Myc Del 1; [27]). The results indicated that the overexpression of YAP induced a ~5-fold increase in c-Myc promoter activity (Fig. 4B). Thus, an increase in the expression of c-Myc might also play a role in pathway through which YAP induces hypertrophy.

Skeletal muscle mass is, in part, regulated by the rate of protein degradation. Protein degradation can be regulated by several proteolytic pathways including the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) that involves E3 ligase enzymes that ubiquitinate and target proteins for degradation [28]. Recently, YAP overexpression was found to inhibit the expression of the muscle specific E3 ligase, atrogin-1, in myoblasts [29]. This finding suggests that YAP may have the potential to suppress protein degradation. We therefore examined whether YAP would be sufficient to decrease the promoter activity of another prominent muscle specific E3 ligase, MuRF1. As shown in Figure 4B, MuRF1 promoter activity was significantly reduced in muscles that had been transfected with YAP (Fig 4C). Hence, a decrease in E3 ligase expression / protein degradation could also contribute to the mechanism through which YAP induces hypertrophy.

Finally, recent studies have shown that myostatin/TGF-β/activin-mediated Smad2/3 signaling contributes to the regulation of protein degradation and skeletal muscle mass, and these effects are exerted, at least in part, through the up regulation of E3 ligase expression [30,31]. Moreover, it has been shown that YAP can bind to Smad7. The YAP/Smad7 interaction facilitates Smad7's recruitment to activated TGF-β receptors and subsequently results in the inhibition TGF-β-induced Smad signaling [32]. Hence, a decrease in Smad2/3 transcriptional activity could potentially explain how YAP promotes a decrease in E3 ligase expression and induces an increase in muscle mass. Therefore, to examine this possibility we co-transfected TA muscles with YAP and a Smad binding element (SBE) luciferase reporter construct which contains 12 Smad CAGA binding motifs. As shown in Figure 4D, our results indicated that the overexpression of YAP induced a ~85% decrease in the activity of the SBE reporter. This finding highlights the potential existence of a pathway through which an increase in the expression of YAP leads to the inhibition of Smad2/3 activity, subsequent E3 ligase expression, and ultimately an increase in muscle mass.

DISCUSSION

This is the first skeletal muscle-based study to demonstrate that the expression of YAP is elevated in response to increased mechanical loading. Given YAP's role in the regulation of cellular growth, this finding suggests that YAP might contribute to the pathway through which increased mechanical loading induces an increase in muscle mass. However, in contrast to our original hypothesis, we did not find a simple relationship between the load-induced changes in YAP expression and the activation of mTORC1 signaling. This finding implies that load-induced changes in YAP expression are unlikely to be the main factor responsible for, at least the initial, mechanical activation of mTORC1. Interestingly though, we did find a very strong correlation between the changes in expression of YAP and that of both P-Akt(T308) and total Akt. Thus, changes in the expression of YAP might contribute to the mechanical regulation of Akt expression and its activity. Alternatively, a separate mechanically-sensitive factor might simultaneously up regulate the expression of both YAP and Akt. Recently, it was reported that YAP might actually be located downstream of mTORC1, with mTORC1 regulating YAP protein levels by inhibiting its autophagy-mediated degradation [33]. Thus, by attenuating autophagy-mediated turnover, the initial mechanical activation of mTORC1 might promote the more delayed increase in expression. This hypothesis is supported by recent evidence that suggests that autophagy may indeed be inhibited during SA-induced overload [34]. Further work is therefore required to explore the potential relationship between mTORC1 activity and YAP protein expression, and to determine whether YAP is necessary for overload-induced muscle hypertrophy.

In addition to the overload-induced increase in total YAP, we also show for the first time that SA induces an increase in YAP S112 phosphorylation. This novel finding suggests that the Hippo signaling pathway, and in particular the Lats1/2 kinases, are sensitive to mechanical stimuli in skeletal muscle in vivo. The reason for the increase in Hippo pathway signaling is unclear; however, given the recent evidence that constitutive activation of YAP results in muscle atrophy and myopathy [35], activation of the Hippo pathway may, in part, be an attempt to limit the magnitude of the increase in YAP transcriptional activity that would occur with the SA-induced increase in total YAP protein.

In this study, we have also shown that a transient overexpression of YAP is sufficient to induce muscle hypertrophy. Surprisingly, however, we discovered that the hypertrophic effect of YAP was mediated by an mTORC1-independent mechanism. Hence, to gain further insight into how YAP induces hypertrophy, we measured the effect of YAP on various molecules that have been implicated in the regulation of muscle mass. The results from these analyses led to the identification of several candidate mechanisms. For instance, we obtained evidence which indicates that the overexpression of YAP induces an increase in the expression of c-Myc. Since c-Myc is a potent activator of ribosome biogenesis, a YAP-induced increase in c-Myc expression might contribute to the hypertrophic response by enhancing rates of protein synthesis via an increase in translational capacity. Consistent with this hypothesis, a recent study in myoblasts demonstrated that constitutively active YAP promotes an increase in the expression of genes involved in ribosome biogenesis and assembly [29]. We also found that YAP promoted an increase in MyoD promoter activity. MyoD is a myogenic regulatory factor that plays an important role in satellite cell activation and proliferation [36]; however, its role in differentiated muscle cells is less clear. Nonetheless, it has been shown that, in adult skeletal muscle, the overexpression of MyoD can induce muscle fiber hypertrophy [26]. Thus, when combined, our results suggest that increases in c-Myc and MyoD expression might contribute to the pathway through which YAP induces muscle hypertrophy. While promising, additional studies will be needed to determine if YAP promotes an increase in the mRNA and protein levels of c-Myc and MyoD, and whether these effects are required for the hypertrophic effects of YAP.

Our results also indicate that YAP markedly reduces Smad2/3 transcriptional activity which, in skeletal muscle, is stimulated by the myostatin/TGF-β/activin receptors [37]. Importantly, YAP has been shown to facilitate the recruitment of inhibitory Smad7 to activated TGF-β receptors [32], and this might explain how YAP inhibited Smad2/3 transcriptional activity. In addition, YAP has also been reported to increase the expression of Follistatin-like 3, a negative regulator of myostatin signaling [29,38], and increase BMP4 expression which can inhibit Smad2/3 activity by stimulating an increase in the competitive Smad1/5/8 signaling network [29,37]. Whether individually, or combined, it is likely that the aforementioned mechanisms contribute to the YAP-mediated reduction in Smad2/3 signaling. Importantly, a decrease in Smad2/3 signaling also has the potential to regulate skeletal muscle mass by inhibiting the expression of UPS E3 ligases. Indeed, in this study we found a YAP-mediated decrease in MuRF1 promoter activity. Furthermore, it has previously been shown that the overexpression of constitutively active YAP inhibits E3 ligase atrogin-1 mRNA expression in myoblasts [29]. Interestingly, Baehr et al. [15] recently reported that the SA-induced response of MuRF1 and atrogin-1 mRNA follows a pattern that is the inverse of our reported changes of YAP protein, suggesting the possibility that YAP could play a role in inhibiting the expression of MuRF1 (and atrogin-1) expression under these conditions. In turn, a YAP-mediated inhibition of MuRF1 (and possibly atrogin-1) expression may play a role in limiting the overall SA-induced increase in ubiquitin proteasome-mediated protein degradation and/or limiting the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of protein targets specific to just these particular E3 ligases. Regardless, our findings suggest that the overexpression of YAP may induce muscle hypertrophy, in part, by suppressing rates of protein degradation via the inhibition of Smad-mediated E3 ligase expression. Additional studies are, however, required to further explore the role of YAP in the regulation of Smad-mediated signaling and protein degradation in skeletal muscle.

Our finding that the overexpression of YAP was sufficient to induce muscle hypertrophy appears to stand in stark contrast to a previous study that found that the overexpression of YAP induced muscle atrophy and signs of myopathy [35]. It is important to point out, however, that the YAP used in the study by Judson et al. (2013) was a constitutively active YAP mutant that was overexpressed for 5-7 weeks. Taken together, this suggests that although the constant and prolonged activation YAP-mediated signaling is eventually deleterious to skeletal muscle, the relatively shorter term activation, perhaps in a pulsatile manner, could be a promising strategy for increasing muscle mass and/or preventing muscle atrophy. Further studies, are needed to explore this possibility.

An important question raised by this study is that: if an increase in the expression of YAP induces hypertrophy through an mTORC1-independent mechanism, and mechanical overload induces hypertrophy via an mTORC1-dependent mechanism [10,39], then what role, if any, does the increase in YAP play in mechanically-overloaded muscles? The answer to this question is not known, but one possibility is that the SA-induced increase in YAP occurs specifically within satellite cells, which in turn, would promote an increase in muscle fiber number, but not necessarily hypertrophy. In support of this possibility it has been shown that satellite cells are necessary for an overload-induced increase in muscle fiber number (i.e., hyperplasia), but they are not required for overload-induced muscle fiber hypertrophy [10,40]. Moreover, it has been shown that YAP is elevated in activated satellite cells and that an increase in YAP significantly contributes to the regulation of myogenesis [29,41]. Thus, increased YAP expression in satellite cells may result in cell proliferation, while an increase in YAP in the mature differentiated muscle fibers appears to result in hypertrophy. Clearly, further work will be needed to identify the cellular location(s) of the overload-induced increase in YAP, and whether YAP is necessary for both overload-induced hyperplasia and hypertrophy.

Finally, during the preparation of this manuscript, Watt, et al., published a study that investigated the role of YAP in the regulation of muscle fiber size [42], and their results are consistent with our data which indicate that the overexpression of YAP induces hypertrophy. Specifically, Watt, et al., analyzed muscles after a more prolonged (4 wk) and viral-mediated overexpression of YAP, and they found that the overexpression of YAP induces hypertrophy while having no effect on markers of mTORC1 signaling [42]. Furthermore, they demonstrated that the hypertrophic effects of YAP are associated with an increase in the rates of protein synthesis [42]. This latter observation is particularly noteworthy because it provides our proposal that YAP may support for increase protein synthesis, in part, through a c-Myc-mediated increase in ribosome biogenesis. However, in contrast to our findings, Watt, et al., concluded that the overexpression of YAP does not lead to a significant reduction in E3 ligase expression. This apparent discrepancy may be due differences in the time point examined after YAP transfection (3 d vs 4 wk), leaving open the possibility that E3 ligase expression may have been suppressed at earlier time points. Unfortunately, Watt, et al., did not examine the effect of YAP on Smad signaling, nor did they examine the effect of increased mechanical loading on YAP expression. Nonetheless, our findings are largely congruent with theirs and, importantly, we extend their findings by showing that increased mechanical loading induces the expression of YAP, but this effect is not associated with the initial mechanical activation of mTORC1. Moreover, we have provided novel insights into the potential mechanisms through which YAP may induce hypertrophy. Thus, our study provides new information on how YAP may exert its growth stimulating effect and this information could lead to the identification of novel molecules / pathways that regulate skeletal muscle mass.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We examined YAP protein expression and mTORC1 activation in overloaded muscles

We also examined the effect of transient YAP overexpression on muscle fiber size

Overload-induced increases in YAP and mTORC1 signaling follow different time courses.

YAP overexpression induced mTORC1-independent muscle fiber hypertrophy

YAP is a novel mTORC1-independent regulator of skeletal muscle mass

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AR057347 (TAH) and AR063256 (CAG and TAH).

Abbreviations (non-standard)

- CSA

cross-sectional area

- LATS1/2

large tumor suppressor kinases 1 and 2

- MCAT

muscle cytosine, adenine and thymine

- mTORC1

mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1

- BMP4

bone morphogenic protein 4

- MuRF1

muscle ring finger 1

- SA

synergist ablation

- SBE

Smad binding element

- TA

Tibialis Anterior

- TEAD

TEA domain

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

- UPS

ubiquitin proteasome system

- YAP

Yes-associated protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhao B, Lei Q-Y, Guan K-L. The Hippo-YAP pathway: new connections between regulation of organ size and cancer. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2008;20:638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao B, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes & Development. 2007;21:2747–2761. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida T. MCAT Elements and the TEF-1 Family of Transcription Factors in Muscle Development and Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:8–17. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin Y, Messmer-Blust AF, Li J. The Role of Transcription Enhancer Factors in Cardiovascular Biology. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2011;21:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao B, et al. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes & Development. 2008;22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low BC, Pan CQ, Shivashankar GV, Bershadsky A, Sudol M, Sheetz M. YAP/TAZ as mechanosensors and mechanotransducers in regulating organ size and tumor growth. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2663–2670. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aragona M, Panciera T, Manfrin A, Giulitti S, Michielin F, Elvassore N, Dupont S, Piccolo S. A Mechanical Checkpoint Controls Multicellular Growth through YAP/TAZ Regulation by Actin-Processing Factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tumaneng K, et al. YAP mediates crosstalk between the Hippo and PI(3)K–TOR pathways by suppressing PTEN via miR-29. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1322–1329. doi: 10.1038/ncb2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman CA. The Role of mTORC1 in Regulating Protein Synthesis and Skeletal Muscle Mass in Response to Various Mechanical Stimuli. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;166:1–53. doi: 10.1007/112_2013_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman CA, Frey JW, Mabrey DM, Jacobs BL, Lincoln HC, You J-S, Hornberger TA. The role of skeletal muscle mTOR in the regulation of mechanical load-induced growth. J Physiol. 2011;589:5485–5501. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.218255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman CA, Mabrey DM, Frey JW, Miu MH, Schmidt EK, Pierre P, Hornberger TA. Novel insights into the regulation of skeletal muscle protein synthesis as revealed by a new nonradioactive in vivo technique. FASEB J. 2011;25:1028–1039. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-168799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki M, McCarthy JJ, Fedele MJ, Esser KA. Early activation of mTORC1 signalling in response to mechanical overload is independent of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signalling. J Physiol. 2011;589:1831–1846. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.205658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman CA, Miu MH, Frey JW, Mabrey DM, Lincoln HC, Ge Y, Chen J, Hornberger TA. A Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B-independent Activation of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling Is Sufficient to Induce Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:3258–3268. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman CA, McNally RM, Hoffmann FM, Hornberger TA. Smad3 Induces Atrogin-1, Inhibits mTOR and Protein Synthesis, and Promotes Muscle Atrophy In Vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1946–1957. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baehr LM, Tunzi M, Bodine SC. Muscle hypertrophy is associated with increases in proteasome activity that is independent of MuRF1 and MAFbx expression. Frontiers in Physiology. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao W, Wang J, Ou C, Zhang Y, Ma L, Weng W, Pan Q, Sun F. Mutual interaction between YAP and c-Myc is critical for carcinogenesis in liver cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;439:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neto-Silva RM, de Beco S, Johnston LA. Evidence for a Growth-Stabilizing Regulatory Feedback Mechanism between Myc and Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of Yap. Developmental Cell. 2010;19:507–520. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Z, Zhang M, Xu K, Liu L, Hou WK, Cai YZ, Xu P, Yao JF. Knockdown of YAP1 inhibits the proliferation of osteosarcoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:1265–72. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schütte U, et al. Hippo Signaling Mediates Proliferation, Invasiveness, and Metastatic Potential of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Translational Oncology. 7:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xin M, et al. Regulation of Insulin-Like Growth Factor Signaling by Yap Governs Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Embryonic Heart Size. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:ra70. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodowska K, Al-Moujahed A, Marmalidou A, Meyer zu Horste M, Cichy J, Miller JW, Gragoudas E, Vavvas DG. The clinically used photosensitizer Verteporfin (VP) inhibits YAP-TEAD and human retinoblastoma cell growth in vitro without light activation. Experimental Eye Research. 2014;124:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez-L A, Squatrito M, Northcott P, Awan A, Holland EC, Taylor MD, Nahle Z, Kenney AM. Oncogenic YAP promotes radioresistance and genomic instability in medulloblastoma through IGF2-mediated Akt activation. Oncogene. 2012;31:1923–1937. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Z, et al. Pi3kcb Links Hippo-YAP and PI3K-AKT Signaling Pathways to Promote Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Survival. Circulation Research. 2014 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J. Rheb Binds and Regulates the mTOR Kinase. Current Biology. 2005;15:702–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benhaddou A, Keime C, Ye T, Morlon A, Michel I, Jost B, Mengus G, Davidson I. Transcription factor TEAD4 regulates expression of Myogenin and the unfolded protein response genes during C2C12 cell differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:220–231. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lagirand-Cantaloube J, Cornille K, Csibi A, Batonnet-Pichon S, Leibovitch MP, Leibovitch SA. Inhibition of atrogin-1/MAFbx mediated MyoD proteolysis prevents skeletal muscle atrophy in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He T-C, et al. Identification of c-MYC as a Target of the APC Pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodine SC, Baehr LM. Skeletal Muscle Atrophy and the E3 Ubiquitin Ligases, MuRF1 and MAFbx/Atrogin-1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol and Metab. 2014;307:E469–E484. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00204.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Judson RN, et al. The Hippo pathway member Yap plays a key role in influencing fate decisions in muscle satellite cells. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:6009–6019. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sartori R, Milan G, Patron M, Mammucari C, Blaauw B, Abraham R, Sandri M. Smad2 and 3 transcription factors control muscle mass in adulthood. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C1248–1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00104.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lokireddy S, McFarlane C, Ge X, Zhang H, Sze SK, Sharma M, Kambadur R. Myostatin Induces Degradation of Sarcomeric Proteins through a Smad3 Signaling Mechanism During Skeletal Muscle Wasting. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1936–1949. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Ferrigno O, Lallemand F, Verrecchia F, L'Hoste S, Camonis J, Atfi A, Mauviel A. Yes-associated protein (YAP65) interacts with Smad7 and potentiates its inhibitory activity against TGF-beta/Smad signaling. Oncogene. 2002;21:4879–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang N, et al. Regulation of YAP by mTOR and autophagy reveals a therapeutic target of tuberous sclerosis complex. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1084/jem.20140341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steiner JL, Gordon BS, Lang CH. Moderate alcohol consumption does not impair overload‐induced muscle hypertrophy and protein synthesis. Physiol Rep. 2015;3 doi: 10.14814/phy2.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Judson RN, et al. Constitutive Expression of Yes-Associated Protein (Yap) in Adult Skeletal Muscle Fibres Induces Muscle Atrophy and Myopathy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berkes CA, Tapscott SJ. MyoD and the transcriptional control of myogenesis. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2005;16:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sartori R, Gregorevic P, Sandri M. TGF and BMP signaling in skeletal muscle: potential significance for muscle-related disease. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014;25:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill JJ, Davies MV, Pearson AA, Wang JH, Hewick RM, Wolfman NM, Qiu Y. The Myostatin Propeptide and the Follistatin-related Gene Are Inhibitory Binding Proteins of Myostatin in Normal Serum. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:40735–40741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bodine SC, et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1014–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarthy JJ, et al. Effective fiber hypertrophy in satellite cell-depleted skeletal muscle. Development. 2011;138:3657–3666. doi: 10.1242/dev.068858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watt KI, et al. Yap is a novel regulator of C2C12 myogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393:619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watt KI, et al. The Hippo pathway effector YAP is a critical regulator of skeletal muscle fibre size. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6048. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.