Abstract

The reproductive role of the fallopian tube is to transport the sperm and egg. The tube is positioned to act as a bridge between the ovary where the egg is released and the uterus where implantation occurs. Throughout reproductive years the fallopian tube epithelium undergoes repetitive damage and regeneration. Although a reservoir of adult epithelial stem cells must exist to replenish damaged cells, they remain unidentified. Here we report isolation of a subset of basally located human fallopian tube epithelia (FTE) that lack markers of ciliated (β-tubulin; TUBB4) or secretory (PAX8) differentiated cells. These undifferentiated cells expressed cell surface antigens: epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM), CD44, and integrin alpha-6 (ITGA6). This fallopian tube epithelial subpopulation was five-fold enriched for cells capable of clonal growth and self renewal suggesting that they contain the fallopian tube epithelial stem-like cells (FTESC). A two-fold enrichment of the FTESC was found in the distal compared to the proximal end of the tube. The distal fimbriated end of the fallopian tube is a well characterized locus for initiation of serous carcinomas. An expansion of the cells expressing markers of FTESC was detected in tubal intraepithelial carcinomas (TIC) and in fallopian tubes from patients with invasive serous cancer. These findings suggest that FTESC may play a role in the initiation of serous tumors. Characterization of these stem-like cells will provide new insight into how the fallopian tube epithelia regenerate, respond to injury and may initiate cancer.

Introduction

The fallopian tube is uniquely equipped with ciliated and secretory cell types which facilitate the locomotion of its precious cargo, the egg, sperm and ultimately the embryo. The ciliated cells direct the transport of egg and sperm by rhythmically beating cilia whose movements are orchestrated by the cyclical changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle [1-3]. The secretory cells produce a nutrient rich fluid that bathes the sperm and egg and provides the environment in which the gametes can find each other [4]. After the reproductive years, the role of the fallopian tube remains unclear. Ciliated and secretory cells atrophy and secretion of tubal fluid ceases [5, 6] . In essence, the fallopian tube becomes a vestigial structure but a potential site for initiation of serous cancers, known to be the deadliest gynecologic malignancy [reviewed in [7]].

The inner surface of the fallopian tube is lined with epithelium in constant contact with the “outside” world through its connection with the uterus and the “inside” world through its direct connection with the peritoneal cavity. The fallopian tube is located adjacent to the ovary and every month during ovulation, the distal end of this tube is exposed to inflammatory factors released at the time of oocyte expulsion [8]. Therefore, cycles of tissue damage, repair and remodeling could be occurring in this epithelial layer. If the fallopian tube accumulates damage with repetitive ovulatory cycles, it must be equipped with regenerative activity in order to rapidly re-establish its normal important reproductive function. To date no one has identified an adult stem cell population of the fallopian tube epithelium.

Three different cell types have been described in the fallopian tube epithelium [9, 10]. Ciliated cells were characterized by pale stained nuclei and long, slender cilia protruding into the tubal lumen [11]. Their distribution is not uniform; progressively increasing numbers of ciliated cells are found from the proximal to distal end [5]. Secretory cells were distinguished from ciliated cells by electron microscopy where their bulging apexes were found to be overhanging the cilia [11]. Although they are similar in height to ciliated cells, secretory cells are generally narrower and contain secretory granules in their apical regions [12, 13]. These cytoplasmic granules have been observed to be clumped to the cilia or floating in the tube lumen [11]. While their distribution spans the entire length of the fallopian tube, secretory cells are found most abundantly in the ampulla where they comprise approximately 50% of all epithelia [14]. Over a century ago, a rare third cell type was identified interspersed between the more abundant ciliated and secretory cells [15]. Investigators who identified this third cell type called it “Stiftchenzellen” which was later referred to as the “peg” cell as it appeared similar to slender pegs driven between the other cells [11, 15]. The peg cell has also been called an “intercalary” cell because these small cells with very little cytoplasm were often found intercalated between the adjacent ciliated and secretory cells [14]. These small, narrow cells have been described historically as non-functioning secretory cells that could possibly be the precursor of the secretory cell [5]; however, their role and function was not investigated. The literature uses the terms “peg” and “intercalary” interchangeably; therefore, we will refer to this distinct cell type in the fallopian tube epithelium as the peg cell. Another cell type called the “basal” or “reserve” cell has been previously observed in the fallopian tube [16]. These cells with a clear cytoplasmic halo were found to be lymphoid based on the expression of leukocyte common antigen and the absence of epithelial markers [16, 17].

Here we characterize the three distinct cell types of the fallopian tube epithelia: ciliated cells, secretory cells, and peg cells. We isolate the peg cell using a cell surface antigenic signature and demonstrate that these cells are the regenerative cells of the fallopian tube in vitro. Furthermore we find that these stem-like cells are concentrated in the fimbriated distal end of the fallopian tube and expanded in tubal specimens from patients with serous carcinomas.

Materials and Methods

Primary human cell preparation

Fallopian tube specimens were obtained from patients undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies (removal of fallopian tubes and ovaries) and tubal ligations using a protocol approved through the UCLA Office for the Protection of Research Subjects (OPRS). Normal fallopian tubes were defined as those not containing cancer. Fallopian tubes were cut into fragments, washed in 5 mM EDTA, and then incubated in 1% trypsin for 45 min at 4°C. Trypsinization was stopped with a DMEM/10% FBS wash, and FTE was separated from the underlying stroma with fine forceps. Then the epithelial fraction was digested in 0.8 mg/ml collagenase in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 5ug/ml insulin at 37°C for 45 min. Dissociation was completed with a 5 min incubation in pre-warmed 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen) followed by 5 passes through a 22 gauge needle. Trypsinization was halted by the addition of DMEM containing 10% FBS.

FACS analysis

Fallopian tube epithelial cells were suspended in DMEM/5% FBS and stained with antibody for 20 min at 4°C with shaking. Antibodies used for FACS sorting are listed in Supporting Information Table S1. FACS cell sorting was performed using the BD FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences).

In vitro culture

The conditions to culture and passage spheres were adapted based on previously described protocols [18]. In short, FACS isolated epithelial single cell preparations were suspended in equal volumes of PrEGM media (Lonza CC-3166) and Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Suspensions were plated around the rim of a 12-well tissue culture plate, allowed to solidify, and then overlaid with warm PrEGM. Spheres were counted after 11-14 days. Hollow spheres with diameters >250 µm were classified as large spheres; other growth was classified as small spheres. To test for self-renewal, spheres were released from matrigel by incubation in 1 mg/ml dispase in PrEGM at 37°C. Liberated spheres were pelleted by centrifugation, washed in PBS, incubated for 5 min in 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA, and passed through a 22 gauge syringe 5 times to yield single cells. Cells were counted by hemocytometer and re-plated. To examine populations capable of producing progeny spheres, large (>250 µm) and small (<125 µm) fluorescently labeled spheres were hand-picked and dissociated. Equal numbers of cells from small or large spheres were combined with unlabeled carrier cells and plated. Outgrowth of fluorescent spheres was scored.

Movie Compilation

Images were photographed every second using the time-lapse application of PictureFrame software (Optronics). Images were compiled as stacks using ImageJ (NIH, rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/), cropped to show a 450 µm field of view and converted to a QuickTime movie at 7 frames per second using the QuickTime plug-in.

Virus and Infection

Lentiviral construction, preparation, titering and spinduction were performed as described previously [19].

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue for immunohistochemistry was either embedded in OCT (optimal cutting temperature compound) or was formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Sorted cells were prepared for immunocytochemistry by performing cytospins in a Shandon Cytospin2 at 800 rpm for 5 min. Frozen tissues and cytospun samples were fixed in ice cold acetone. Paraffin sections were subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer pH6. Antibodies used for IHC are listed in Supporting Information Table S2. Stained slides were imaged on either an Olympus BX51 upright microscope equipped with a Prior Lumen 2000 fluorescent source, Optronics macrofire CCD camera and Optronics PictureFrame software (dual stained samples) or a Zeiss Axiovert with EXFO X-Cite series 120Q source, Zeiss McR camera and Axiovision software (triple stained samples). To quantify number of positive cells on stained specimens, 5 random high powered fields of view were counted per sample.

Statistics

All experimental data are presented as the mean ± SD. The statistical significance of differences between groups was analyzed using Student’s T-test.

Results

A minor subpopulation of human fallopian tube epithelia gives rise to clonal self-renewing spheres

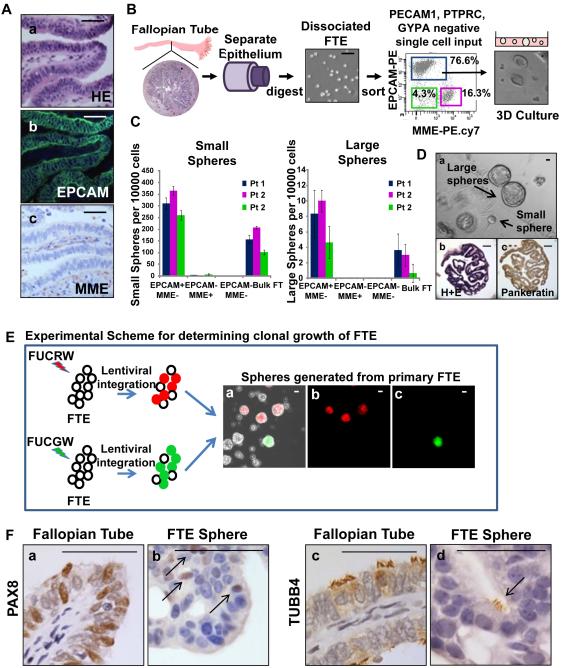

We established protocols for isolation of total fallopian tube epithelia (FTE) from human fallopian tube specimens. Based on immunostaining epithelial cell adhesion marker (EPCAM) marked all FTE while membrane metallo-endopeptidase (MME) marked fallopian tube stroma (Fig. 1A a-c). Normal fallopian tube epithelia were mechanically separated from human fallopian tube segments and digested using collagenase and trypsizination [19] (Fig. 1B). This cellular population was dissociated into single cells and depleted for lineage markers (Lin−): Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type C (PTPRC, hematopoietic), Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM1, endothelial) and Glycophorin A (GYPA, red blood cells). Flow cytometry analysis showed the presence of three subpopulations based on EPCAM and MME expression (Fig. 1B). Predominance of this cellular preparation was epithelial based on expression of EPCAM (77%) (Fig. 1B). The growth capacity of EPCAM+MME−Lin−, EPCAM−MME+Lin− and EPCAM−MME−Lin− was compared to bulk dissociated FTE in a 3-dimensional (3D) matrigel growth assay. Only the EPCAM+MME−Lin− fraction was able to give rise to spheroid structures in culture (Fig. 1C). Dissociated FTE were capable of giving rise to large and small spheres (Fig. 1C&D and Supporting Information S1A). Large spheres were defined as any sphere equal to or greater than 250 µm in greatest diameter (Supporting Information S1A). The number of regenerated spheres was linear relative to cell input (Supporting Information Fig. S1B). The frequency of forming a large sphere was 26 fold lower than all spheres (Supporting Information Fig. S1B). Both large and small spheres were released from matrigel, dissociated into single cells, and re-plated to assess serial passaging capability. Only large spheres were able to give rise to a large and small daughter sphere while small spheres could only propagate into a few small spheres (Supporting Information Fig. S1C). Cells dissociated and isolated from spheres were capable of self-renewal demonstrated by multiple passages in vitro (Supporting Information Fig. S1D). To assess the clonality of regenerated spheres, human FTE were infected either with FUCGW [20] (green color marked) or FUCRW [21] (red color marked) lentivirus mixed and plated together in vitro (Fig. 1E). Regenerated spheres in this assay were only monochromatic and chimeric colored spheres were not seen (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that FTE spheres are clonal in origin and arise from a single cell.

Figure 1. Isolation and in vitro clonal growth of adult human fallopian tube epithelia.

(A) All FTE expressed the EPCAM cell surface marker (a,b), while supporting stroma expressed MME (a,c). (B) Expression of stromal and epithelial markers were examined by flow cytometry in mechanically isolated cells from fresh fallopian tube specimens. Based on EPCAM and MME expression, three populations were identified and plated in a matrigel culture assay. Subsets of cells generated spheroid structures. (C) Only the EPCAM+MME−Lin− epithelial fraction was capable of generating large and small spheres. (D) FTE generated both large (>250 µm) and small (<250 µm) spheres (a), that were single layered and contain papillary structures reminiscent of the fallopian tube (b). Sphere cells were epithelial based on expression of pankeratin (c). (E) FTE cells were infected with either FUCRW (marked with red fluorescent protein [RFP]) or FUCGW (marked with green fluorescent protein [GFP]) lentivirus and mixed prior to plating. Regenerated spheres were either unlabeled (uninfected), RFP positive or GFP positive. Chimeric spheres were not detected suggesting that one cell gives rise to each sphere. Scale bars equal 100 µm. (F) Similar to native fallopian tube, subsets of FTE sphere cells were secretory based on PAX8 expression (a vs. b) or ciliated based on TUBB4 expression (c vs. d). All scale bars equal 50 µm.

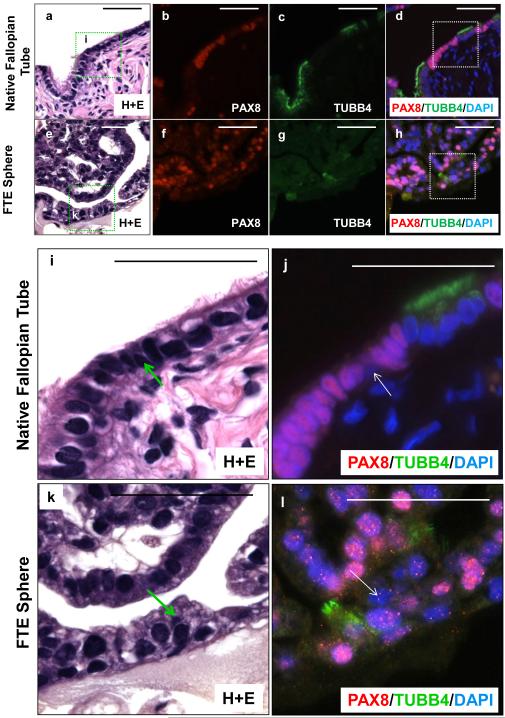

Regenerated large spheres architecturally resembled the fallopian tube based on the presence of papillary projections into a hollow tube (Fig. 1D a-c). The cellular composition of these spheres was epithelial based on expression of pankeratin (Fig. 1D c). Similar to the native fallopian tube epithelium both secretory (PAX8 positive) [22] and ciliated cells (β-tubulin; TUBB4 positive) were detected in regenerated spheres (Fig. 1F a&c vs. b&d). In fact, beating functional cilia could be detected in some regenerated spheres (Supplemental online video 1). Subsets of cells in native fallopian tube lacked expression of PAX8 and TUBB4 (Fig 2a-d&i-j). These cells are typically basally located. Similarly, cells in the regenerated spheres lacked expression of PAX8 or TUBB4 (Fig 2e-h&k-l). These rare basally located cells in the spheres and the native fallopian tube were non-ciliated and non-secretory and resembled the historically described Peg cell of the fallopian tube. We found that approximately 1 in 40 FTE cells were capable of giving rise to spheres (large and small) (Supporting Information Fig. S1B). But only 1 in 1000 FTE could produce large spheres capable of self-renewal with evidence of multi-lineage differentiation (Supporting Information Fig. S1B). Given that only the large spheres were able to self-renew in vitro, all quantitative comparisons were made between the numbers of large spheres in subsequent analyses of this manuscript.

Figure 2. Multi-lineage differentiation of dissociated human FTE cells evidenced by formation of all three fallopian tube cell types.

Sections of both native fallopian tube (a-d, i-j) and FTE spheres (e-h, k-l) co-stained for secretory marker PAX8 and ciliated marker TUBB4 demonstrated that most cells were either secretory or ciliated. Rare basally located cells found in both native fallopian tube (magnified image i-j) and FTE spheres (magnified image k-l) were negative for both PAX8 and TUBB4. All scale bars equal 50 µm.

Basally located, undifferentiated FTE cells marked with CD44 are the peg cells of the fallopian tube

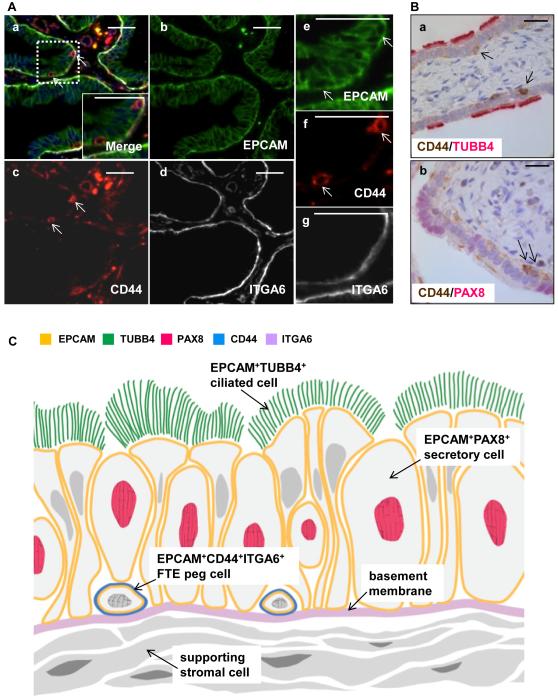

During development the fallopian tube and uterus originate from the same source, the mullerian ducts [reviewed in [23]]. The mullerian duct epithelium, a derivative of coelomic epithelium, gives rise to both the fallopian tube and endometrial epithelial cells [24, 25]. Previous work in our laboratory has shown that CD44 positive cells in contact with the basement membrane mark the mouse uterine epithelial regenerative cells (Janzen DM et al, manuscript in review). Given that the fallopian tube and endometrial epithelium share a common embryologic origin we looked for expression of CD44 positive cells in the fallopian tube. Integrin alpha 6 (ITGA6) marked the basement membrane of all fallopian tube epithelia (Fig. 3A a,d&g). Rare, basally located CD44 positive cells were identified in the fallopian tube epithelial layer (Fig. 3A a,c&f). The basally located CD44 positive cells were neither secretory nor ciliated as they did not express TUBB4 or PAX8 (Fig. 3B a&b). The location of these basally located undifferentiated CD44 positive cells is the same as the previously described peg cells (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. A subpopulation of CD44 positive cells adjacent to the basement membrane do not express markers of ciliated or secretory cells.

(A) Immunohistochemistry revealed EPCAM positive epithelial cells (a,b,e) were bound by a basement membrane expressing ITGA6 (a,d,g). Rare, small basally located cells immediately adjacent to the basement membrane expressed both EPCAM and CD44 (a, c, f). (B) Basally located CD44 positive cells expressed neither the ciliated marker TUBB4 (a) or the secretory marker PAX8 (b). (C) Schematic of a third undifferentiated cell interspersed among the ciliated and secretory cells, marked with EPCAM, CD44, and ITGA6. This cell marked with EPCAM, CD44, and ITGA6 is the peg cell of the fallopian tube. All scale bars equal 25 µm.

The basally located CD44 positive population is enriched for sphere forming activity

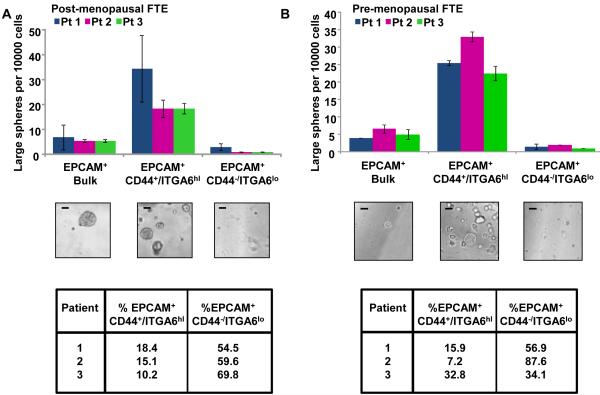

We asked if the basally located CD44 positive cells were the regenerative epithelial cells of the fallopian tube. EPCAM+CD44+ITGA6hiLin− cells were isolated from normal human fallopian tubes. To account for any hormonal variations that may be induced in FTE, normal fallopian tubes were obtained from two cohorts of women: post-menopausal women undergoing tubal removal for non-cancerous indications and pre-menopausal women undergoing resection of the fallopian tube for contraceptive purposes. The in vitro growth of FTE was compared to bulk and depleted epithelia. In all fallopian tube specimens majority of the large sphere forming potential resided in the EPCAM+CD44+ITGA6hiLin− fraction suggesting these cells contain the human FTE stem-like cells (FTESC) (Fig. 4A&B and Supporting Information S2A-C). In both hormonal conditions, this cellular fraction contained the bulk of the in vitro regenerative activity (Fig. 4A&B). A significant difference was not detected in the large sphere forming potential of pre vs. post menopausal isolated FTE (P=0.86). On average we found that approximately 17% (± 8.9%) of FTE expressed the FTESC antigenic profile (Fig. 4A&B). The in vitro growth capacity of the FTESC was 5 fold (± 0.7x) higher than bulk and 18 fold (± 3.6x) higher compared to FTESC- cells (Supporting Information S2C). Overall these results suggest that this antigenic profile isolates a population of FTE with stem-like activity. Cells marked with the FTESC antigenic profile reside in the same location as the historically described peg cell; therefore, the peg cell is the FTE stem-like cell. The peg cell can be isolated based on expression of EPCAM, CD44 and ITGA6.

Figure 4. The EPCAM+CD44+ITGA6hiLin− population are the stem-like cells of the FTE.

(A) In postmenopausal specimens, 15% (± 4.1%) of FTE were EPCAM+ CD44+ITGA6hiLin−. These cells contained the predominance of large sphere forming potential, and were enriched 4.8 fold (± 0.1x) for growth compared to bulk FTE and 16.5 fold (± 4.3x) compared to the depleted fraction. (B) Similarly, in pre-menopausal patients undergoing post-partum tubal ligation, the EPCAM+CD44+ITGA6hiLin− signature was identified in 19% (± 13.0%) of FTE. This cellular fraction was enriched 5.7 fold (± 1.0x) for in vitro growth compared to bulk FTE and a 16.8 fold (± 0.4x) compared to the depleted fractions. No significant difference was seen between the percentages of cells expressing the EPCAM+CD44+ITGA6hiLin− antigenic profile under these differing hormonal conditions (P = 0.65 by t test). All scale bars equal 100 µm.

Due to the proximity of the ovary to the fallopian tube, the possibility of bi- and/or unidirectional exchange of epithelial cells may exist between these two organs. The expression of CD44 positive cells was examined in eight independent normal ovary specimens (Supporting Information Fig. S3). OSE was identified by expression of pan-keratin. CD44 expression was not detected in the majority of the OSE examined. Therefore, it is unlikely that CD44 positive cells in the fallopian tube originate from the OSE.

Localization and characterization of fallopian tube epithelial stem-like cells

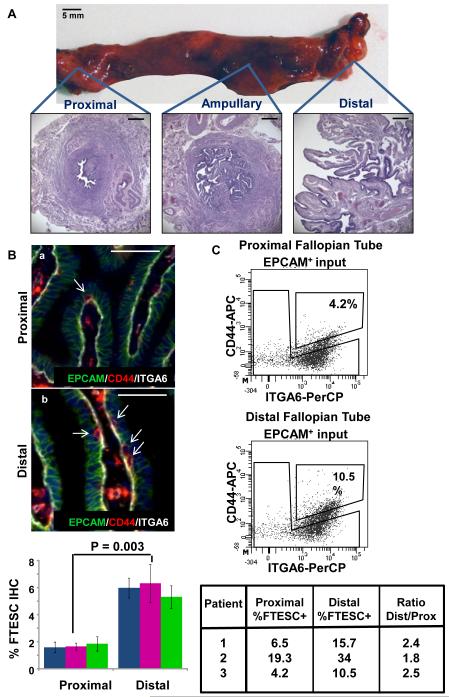

The fallopian tube is a long hollow structure and its epithelial cellular composition is dramatically different in the proximal (adjacent to the uterus) vs. the distal fimbriated end (adjacent to the ovary) (Fig. 5A) [26]. We asked whether the stem cells of the FTE would be differentially distributed in the fallopian tube. First to visually localize and quantify these cells, the number of EPCAM/CD44/ITGA6 triple positive cells was quantified in the distal vs. proximal histologic sections of three independent normal fallopian tube specimens (Fig. 5B). An approximately 3-fold increase in EPCAM/CD44/ITGA6 triple positive cells was noted in the distal fimbriated end of the fallopian tube. We then isolated FTE from proximal and distal portions of three normal independent human fallopian tube specimens. Using FACS analysis, EPCAM+CD44+ITGA6hiLin− population was quantified and compared in these two different regions of the tube (Fig. 5C). Based on this analysis, we observed a 2-fold difference in the percentage of cells expressing the FTE stem-like signature in the distal vs. proximal fallopian tube (Fig. 5C). Differences in the percentage of FTESC detected via two methods (immunohistochemistry vs. FACS) may be due to increased sensitivity of FACS analysis in detecting cell surface antigens vs. visual quantification by immunohistochemistry. Collectively these results demonstrate that FTE stem-like cells reside throughout the fallopian tube but are more concentrated in the distal fimbriated end. The concentrated location of FTESC in the distal tube may be a biologic adaptation for repair because this fallopian tube portion may be at greater risk for injury on a monthly basis with ovulation [8].

Figure 5. FTESC are distributed across the fallopian tube, but are concentrated in the distal end.

(A) A gross example of a human fallopian tube and its cross sectional histology. Scale bars equal 5 mm and 500 µm. (B) Proportions of EPCAM+CD44+ITGA6hi cells in matched distal and proximal FT specimens were evaluated by IHC. A 3-fold increase in the FTESC positive population was observed in the distal compared to proximal fallopian tube. Scale bars equal 50 µm. (C) A two-fold greater percentage of FTESC was observed in the distal compared to proximal FTE analyzed by flow cytometry.

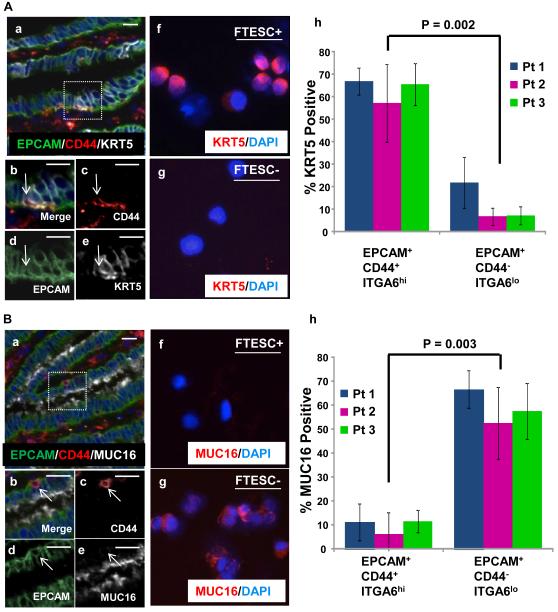

To further characterize the possible heterogeneity in the FTE populations, we examined the expression of other epithelial markers that could be differentially expressed in the FTESC+ vs. FTESC- fractions. Cytokeratin 5 (KRT5) is a filament protein that is expressed by epithelial cells and may play a role in maintaining the proliferative capacity of basally located epithelia [27]. We examined the expression of KRT5 in the fallopian tube stem-like cell fraction compared to differentiated FTE by immunostaining tissue sections of normal fallopian tube. We found that the majority of the basally located CD44 positive cells also expressed KRT5 (Fig. 6A a-e). The FTESC+ and FTESC- cells were also isolated from three independent specimens and analyzed for KRT5 expression. Similarly, majority of isolated FTESC+ cells expressed KRT5 (Fig. 6A f-h). Overall these results show that FTESC express KRT5, a basal marker expressed on other stem-like cells such as those found in the lung and prostate epithelium [28, 29].

Figure 6. Predominance of FTESC express KRT5 but not MUC16.

(A) In stained fallopian tube sections, many CD44 positive epithelial cells were found to co-express KRT5 (a-e). Cytospin analysis of FACS isolated cells confirmed that the majority of FTESC positive cells also expressed KRT5 (f,h), while most FTESC negative cells did not express KRT5 (g,h). (B) Basally located EPCAM positive CD44 positive epithelial cells in human fallopian tube sections were negative for MUC16 expression (a-e). Cytospin analysis performed on flow cytometry isolated cells demonstrated that the majority of isolated FTESC were MUC16 negative (f,h). Conversely, FTESC negative populations were predominantly positive for MUC16 expression (g,h). Scale bars equal 25 µm.

MUC16 (also known as CA125) is part of the family of mucins which are glycosylated proteins expressed on epithelial cells in many different tissues [30]. They have been recognized as antigens on the surface of epithelial cancers [31]. For example, MUC1 is known to be expressed on differentiated epithelial cells of the human colon and on colorectal tumor cells [32, 33]. We examined the expression of MUC16, an ovarian cancer antigen [34]. Based on immunostaining the predominance of basally located CD44 positive cells did not express MUC16 (Fig. 6B a-e). To better assess expression of MUC16 in FTE, percentage of MUC16 positive cells was measured and quantified on isolated FTESC+ and FTESC- fractions from three independent patients (Fig. 6B f-h). Majority of differentiated non-stem-like FTE expressed MUC16, while the majority of FTESC were MUC16 negative (Fig. 6B f-h). These results demonstrate differential expression of two other markers in FTESC+ vs. FTESC- fractions.

FTE stem-like cells are expanded in the fallopian tube epithelium of patients with serous cancer

The FTE is actively being explored as a site of initiation for serous cancers [35-37]. Dysplastic lesions identified typically in the distal end of the fallopian tube have been hypothesized to be precursor lesions for invasive serous cancers [38-41]. These lesions were found originally in patients at high risk for serous ovarian cancer undergoing prophylactic removal of their ovaries and fallopian tubes [42]. Based on histology and tumor protein p53 (TP53) expression; these dysplastic lesions were termed tubal intraepithelial carcinomas (TIC) [38, 40]. The expression of CD44 and KRT5 was examined in two clinical samples diagnosed as TIC. We found an expansion of CD44 and KRT5 positive cells in dysplastic lesions of the FTE from these patients (Supporting Information, Fig. S4).

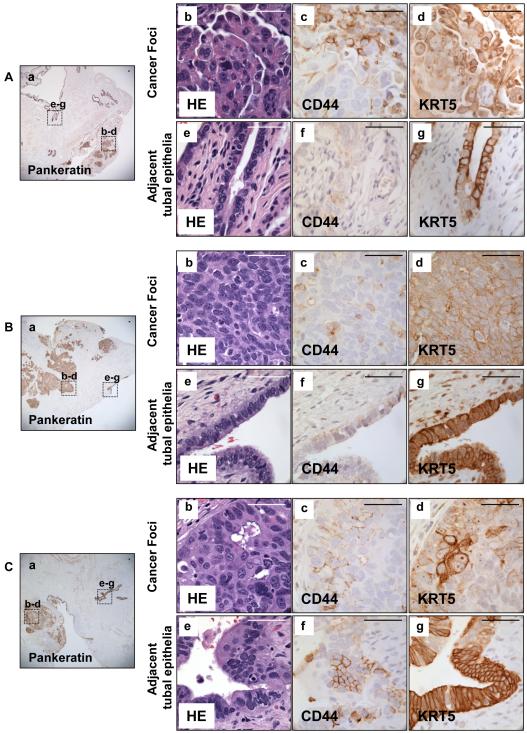

We wanted to see if markers of FTE stem-like cells could also be found in patients with invasive serous carcinomas. Clinical specimens of three patients with known disseminated serous carcinoma were examined for expression of CD44 and KRT5 in tumor sites and in adjacent normal appearing tubal epithelium (Fig. 7). In all three clinical samples, an expansion of CD44 and KRT5 positive cells was detected in serous tumors. Interestingly, we found increased numbers of CD44 and KRT5 positive cells in the adjacent normal appearing tubal epithelium of these patients with serous cancers. This was quite different to previously identified rare CD44 and KRT5 positive cells found in the normal tubal epithelium. Collectively, the expansion of cells marked with the FTESC signature in TICs and serous carcinomas suggest that these cells may play a role in the initiation of serous cancers.

Figure 7. Expansion of CD44 and KRT5 positive cells in tubal epithelium and adjacent tumor nodules was detected in three patients with serous carcinoma.

Histologic sections were obtained from fallopian tubes of three patients with serous carcinoma. Pankeratin marked all epithelia (Aa, Ba, Ca). Many CD44 and KRT5 positive cells were detected in serous tumor samples (A b-d, B b-d, C b-d). Expansion of both KRT5 and CD44 positive cells was observed in normal appearing tubal epithelia adjacent to these tumor foci (A e-g, B e-g, C e-g). Scale bars equal 50 µm.

Discussion

Every month, collagenases, proteases, and prostaglandins circulate to break down the follicular wall of the ovary during ovulation [43]. Due to its vicinity to the ovary, the distal end of the fallopian tube is exposed to these inflammatory agents resulting in potential repetitive damage to the fallopian tube [8]. For example, just prior to ovulation, sheets of ciliated and secretory cells proliferate and become stratified into layers throughout the entire fallopian tube [5, 44]. This may be an anticipatory response to cellular damage that can occur with ovulation. After ovulation, the fallopian tube epithelium reverts back to a single layer with fragmented cells shed into the lumen [5, 44]. In preparation for ovulation and transport of the egg, the number of ciliated cells also increases at the distal end of the tube [45, 46]. From these observations, it is clear that the fallopian tube is dynamically regenerating during reproductive cycles. Our study characterizes a subpopulation of FTE with stem-like activity and demonstrates that these cells are the historically described peg cells. The stem-like cells are distributed throughout the fallopian tube but are concentrated in the distal end.

Mounting evidence has suggested that the origin for disseminated serous cancers may not reside in the ovary but in the adjacent fallopian tube [38-41, 47, 48]. Studies have reported the co-existence of tubal intraepithelial carcinomas (TIC) located in the distal end of the fallopian tube in a majority of patients with high-grade pelvic serous carcinomas [39, 40]. It is now believed that dissemination of serous cancers may occur by exfoliation of tumor cells originating from the distally located TICs [reviewed in [7]]. Recent mouse models have shown transformation of human and mouse FTE into serous cancers through multiple genetic mutations [35, 37]. These data suggest that serous cancers may arise from fallopian tube epithelia. We find expansion of cells expressing CD44 and KRT5 in tubal intraepithelial carcinomas, serous tumors and normal appearing fallopian tube epithelium in patients with a diagnosed of invasive serous cancer. It is therefore possible that the FTE stem-like cells could be precursors for serous cancers.

Most FTE stem-like cells do not express MUC16 (CA 125). Although MUC16 (CA 125) is the best known tumor marker for serous cancers [34, 49], multiple clinical trials have shown it is a poor biomarker for early detection and screening [50-52]. In fact to date, no reliable tumor marker has been identified for screening of this deadly disease. If the normal FTE stem-like cell, which does not express MUC16 (CA 125), is the initiating cell for serous cancers, then it is not surprising that MUC16 (CA 125) levels are normal in early disease. These findings collectively may explain failure of MUC16 (CA 125) in screening and early detection of serous carcinomas. Further work in our lab will involve delineation of the role of the FTE stem-like cell as a potential cell of origin of serous cancers with the goal of identifying better biomarkers for screening and early detection of this lethal disease.

Conclusions

Here we provide the first description for isolation of human epithelial stem-like cells from the fallopian tube. These cells are capable of multi-lineage differentiation and self-renewal in vitro. The FTE stem-like cells are basally located, undifferentiated, and found concentrated in the distal end of the tube. We also find expansion of cells that express these stem-like markers in human serous tumor specimens and in adjacent normal tubal epithelium from the same patients. The distal fallopian tube is a potential site for serous cancer initiation. We predict that the fallopian tube epithelial stem-like cells concentrated in the distal end may play a role in initiation of this deadly disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Brooke Nakamura for technical support. We thank Drs. Andrew Goldstein and Yang Zong for helpful conversations related to this project. We thank the UCLA Tissue Procurement Core Laboratory for their assistance in providing human fallopian tube specimens. SM is supported by a Veteran Affairs CDA-2 Career Development Award, a gift from the Scholars in Translational Medicine Program, Mary Kay Foundation Award, Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigators Award, STOP Cancer Award and the Broad Stem Cell Research Center Research Award. This work was also supported by the Liz Tilberis Scholars Program from the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund, Inc., the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation St. Louis Ovarian Cancer Awareness Research Grant and the Ovarian Cancer Circle inspired by Robin Babbini. ONW is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Critoph FN, Dennis KJ. Ciliary activity in the human oviduct. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1977;32:602–603. doi: 10.1097/00006254-197709000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahmood T, Saridogan E, Smutna S, et al. The effect of ovarian steroids on epithelial ciliary beat frequency in the human Fallopian tube. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:2991–2994. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.11.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyons RA, Djahanbakhch O, Mahmood T, et al. Fallopian tube ciliary beat frequency in relation to the stage of menstrual cycle and anatomical site. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:584–588. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leese HJ, Tay JI, Reischl J, et al. Formation of Fallopian tubal fluid: role of a neglected epithelium. Reproduction. 2001;121:339–346. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crow J, Amso NN, Lewin J, et al. Morphology and ultrastructure of fallopian tube epithelium at different stages of the menstrual cycle and menopause. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:2224–2233. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correr S, Makabe S, Heyn R, et al. Microplicae-like structures of the fallopian tube in postmenopausal women as shown by electron microscopy. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:219–226. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurman RJ, Shih Ie M. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2010;34:433–443. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf3d79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King SM, Hilliard TS, Wu LY, et al. The impact of ovulation on fallopian tube epithelial cells: evaluating three hypotheses connecting ovulation and serous ovarian cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:627–642. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferenczy A, Richart RM, Agate FJ, Jr., et al. Scanning electron microscopy of the human fallopian tube. Science. 1972;175:783–784. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4023.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eddy CA, Pauerstein CJ. Anatomy and physiology of the fallopian tube. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980;23:1177–1193. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198012000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novak E, Everett HS. Cyclical and other variations in the tubal epithelium. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1928;16:499–530. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodruff JD, Pauerstein CJ. The fallopian tube; structure, function, pathology, and management. Williams & Wilkins Co.; Baltimore, MD: 1969. pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lentz TL. Cell fine structure; an atlas of drawings of whole-cell structure. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1971. p. 437. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fredericks C. Morphological and functional aspects of the oviduct epithelium. In: Siegler AM, editor. The Fallopian Tube: Basic studies and clinical contributions. Futura; New York, NY: 1986. pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frommel E. Vol. 28. Arch. Gynaek; Munchen: 1886. Beitrag zur Histologie der Eileiter. Verh.dtsch.gpak. Ges. p. 458. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters WM. Nature of "basal" and "reserve" cells in oviductal and cervical epithelium in man. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:306–312. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.3.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris H, Emms M, Visser T, et al. Lymphoid tissue of the normal fallopian tube--a form of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1986;5:11–22. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xin L, Lukacs RU, Lawson DA, et al. Self renewal and multilineage differentiation in vitro from murine prostate stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2760–2769. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Memarzadeh S, Zong Y, Janzen DM, et al. Cell-autonomous activation of the PI3-kinase pathway initiates endometrial cancer from adult uterine epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17298–17303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012548107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xin L, Teitell MA, Lawson DA, et al. Progression of prostate cancer by synergy of AKT with genotropic and nongenotropic actions of the androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7789–7794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602567103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Memarzadeh S, Cai H, Janzen DM, et al. Role of autonomous androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer initiation is dichotomous and depends on the oncogenic signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7962–7967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105243108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowen NJ, Logani S, Dickerson EB, et al. Emerging roles for PAX8 in ovarian cancer and endosalpingeal development. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masse J, Watrin T, Laurent A, et al. The developing female genital tract: from genetics to epigenetics. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:411–424. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082680jm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guioli S, Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R. The origin of the Mullerian duct in chick and mouse. Dev Biol. 2007;302:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orvis GD, Behringer RR. Cellular mechanisms of Mullerian duct formation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2007;306:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Critoph FN, Dennis KJ. The cellular composition of the human oviduct epithelium. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 1977;84:219–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1977.tb12559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alam H, Sehgal L, Kundu ST, et al. Novel function of keratins 5 and 14 in proliferation and differentiation of stratified epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 22:4068–4078. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rock JR, Onaitis MW, Rawlins EL, et al. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12771–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906850106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein AS, Huang J, Guo C, et al. Identification of a cell of origin for human prostate cancer. Science. 2010;329:568–571. doi: 10.1126/science.1189992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollingsworth MA, Swanson BJ. Mucins in cancer: protection and control of the cell surface. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:45–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rump A, Morikawa Y, Tanaka M, et al. Binding of ovarian cancer antigen CA125/MUC16 to mesothelin mediates cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9190–9198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ajioka Y, Allison LJ, Jass JR. Significance of MUC1 and MUC2 mucin expression in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:560–564. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.7.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byrd JC, Bresalier RS. Mucins and mucin binding proteins in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:77–99. doi: 10.1023/a:1025815113599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin BW, Dnistrian A, Lloyd KO. Ovarian cancer antigen CA125 is encoded by the MUC16 mucin gene. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:737–740. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karst AM, Levanon K, Drapkin R. Modeling high-grade serous ovarian carcinogenesis from the fallopian tube. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levanon K, Ng V, Piao HY, et al. Primary ex vivo cultures of human fallopian tube epithelium as a model for serous ovarian carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29:1103–1113. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Coffey DM, Creighton CJ, et al. High-grade serous ovarian cancer arises from fallopian tube in a mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3921–3926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117135109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol. 2007;211:26–35. doi: 10.1002/path.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Przybycin CG, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM, et al. Are all pelvic (nonuterine) serous carcinomas of tubal origin? Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1407–1416. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ef7b16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2007;31:161–169. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213335.40358.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crum CP, Drapkin R, Kindelberger D, et al. Lessons from BRCA: the tubal fimbria emerges as an origin for pelvic serous cancer. Clin Med Res. 2007;5:35–44. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2007.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed Fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2001;195:451–456. doi: 10.1002/path.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Machelon V, Emilie D. Production of ovarian cytokines and their role in ovulation in the mammalian ovary. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1997;8:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amso NN, Crow J, Lewin J, et al. A comparative morphological and ultrastructural study of endometrial gland and fallopian tube epithelia at different stages of the menstrual cycle and the menopause. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:2234–2241. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verhage HG, Bareither ML, Jaffe RC, et al. Cyclic changes in ciliation, secretion and cell height of the oviductal epithelium in women. Am J Anat. 1979;156:505–521. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001560405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donnez J, Casanas-Roux F, Caprasse J, et al. Cyclic changes in ciliation, cell height, and mitotic activity in human tubal epithelium during reproductive life. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:554–559. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, et al. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2006;30:230–236. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000180854.28831.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crum CP, Drapkin R, Miron A, et al. The distal fallopian tube: a new model for pelvic serous carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:3–9. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328011a21f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bast RC, Jr., Klug TL, John E, et al. A radioimmunoassay using a monoclonal antibody to monitor the course of epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:883–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198310133091503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buys SS, Partridge E, Greene MH, et al. Ovarian cancer screening in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial: findings from the initial screen of a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1630–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobs IJ, Skates SJ, MacDonald N, et al. Screening for ovarian cancer: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1207–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobayashi H, Yamada Y, Sado T, et al. A randomized study of screening for ovarian cancer: a multicenter study in Japan. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:414–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.