Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether a novel endpoint of time to prerandomization monthly seizure count could be used to differentiate efficacious and nonefficacious therapies in clinical trials of new add-on antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).

Methods:

This analysis used data from 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trials of perampanel as an add-on therapy in patients with epilepsy who were experiencing refractory partial seizures: studies 304 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00699972), 305 (NCT00699582), and 306 (NCT00700310). Time to prerandomization monthly seizure count was evaluated post hoc for each trial, and findings were compared with the original primary outcomes (median percent change in seizure frequency and 50% responder rate). Outcomes were assessed for all partial-onset seizures, secondarily generalized (SG) tonic-clonic seizures only, and complex partial plus SG (CP + SG) seizures.

Results:

Perampanel 4–12 mg significantly prolonged median time to prerandomization monthly seizure count, generally by more than 1 week, compared with placebo, across all 3 studies, consistent with the original primary outcomes. Analysis of SG seizures only, and CP + SG seizures, also indicated a significantly prolonged median time to prerandomization monthly seizure count with perampanel 8 mg and 12 mg compared with placebo.

Conclusions:

Time to prerandomization monthly seizure count is a promising novel alternative to the standard endpoints of median percent change in seizure frequency and 50% responder rates used in trials of add-on AEDs. Use of this endpoint could reduce exposure to placebo or ineffective treatments, thereby facilitating trial recruitment and improving safety.

Phase III trials to evaluate add-on antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in patients with partial-onset seizures usually involve a placebo-controlled randomized treatment phase lasting 12–24 weeks.1–17 While this traditional study design remains the gold standard, it requires many patients to receive placebo, or a possibly ineffective treatment, for long periods, discouraging patient participation. Therefore, novel approaches are needed that reduce placebo exposure while still providing evidence of treatment efficacy.

We consider a novel time-to-event endpoint, time to prerandomization monthly seizure count, which assesses how long it takes for each patient to reach the number of seizures that he or she typically experienced over 28 days prior to randomization. It was anticipated that if treatment had no antiseizure effect, patients would remain in a trial for an average of 28 days, but if seizure frequency was reduced, patients would continue treatment for longer. Conversely, if seizure frequency increased, then exit would occur sooner, as would be appropriate.

To determine whether this approach could differentiate efficacious and nonefficacious therapies in clinical trials of add-on AEDs, we performed a post hoc analysis of time to prerandomization monthly seizure count using data from completed phase III trials of perampanel.10,11,14 Outcomes were compared with those previously obtained using the original study endpoints to determine whether separation from placebo was consistent. Analyses were performed for all seizure types, as well as for secondarily generalized (SG) tonic-clonic seizures and complex partial plus SG (CP + SG) seizures, which are considered the most clinically severe seizure type and can be identified more objectively.

METHODS

Overall phase III program.

Data from 3 multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trials were used to evaluate the efficacy and safety of perampanel as an add-on therapy in patients with epilepsy who were experiencing refractory partial seizures: studies 304 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00699972),10 305 (NCT00699582),11 and 306 (NCT00700310).14 Eligible patients in these 3 trials were individuals aged 12 years or older who had a diagnosis of simple or complex partial-onset seizures, with or without secondary generalization. Furthermore, patients must have failed at least 2 AEDs within the past 2 years, have had at least 5 partial-onset seizures during the 6-week baseline period (with ≥2 partial seizures per each 3-week period and no 25-day seizure-free period in the 6-week period), and have been on a stable type and dose regimen of up to 3 approved AEDs.

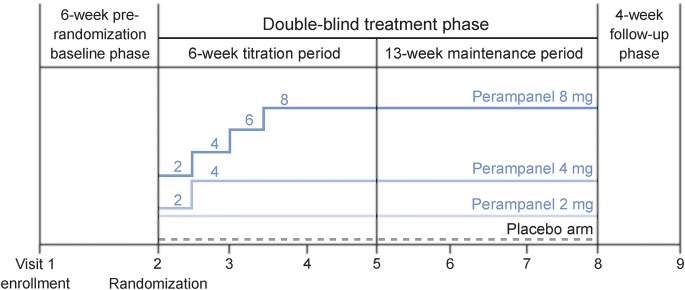

The trials consisted of 4 study phases: a 6-week prerandomization baseline phase, a 19-week double-blind treatment phase (divided into a 6-week titration period and a 13-week maintenance period), and a 4-week post-treatment follow-up phase (figure 1). During the baseline phase, pretreatment seizure frequency was assessed in all patients. Eligible patients were then randomized to once-daily add-on treatment with either placebo or perampanel at different doses. More specifically, studies 304 and 305 evaluated perampanel at doses of 8 mg or 12 mg, while study 306 used doses of 2 mg (noneffective dose), 4 mg (minimally effective dose), or 8 mg. During the 6-week titration period, daily perampanel dose was uptitrated in 2-mg weekly increments until the randomized dose was reached. Then, during the subsequent maintenance period, patients underwent stable dosing and the efficacy of perampanel was evaluated. Patients who discontinued treatment during the maintenance period had a follow-up visit 4 weeks after stopping treatment to assess safety and efficacy.

Figure 1. Design of study 306.

Studies 304 and 305 were based on similar designs, but with patients randomized to placebo or daily perampanel doses of 8 or 12 mg.

Data on seizure frequency and seizure type were recorded in daily diaries maintained by the patients or caregivers. The primary endpoint for perampanel registration in the United States was the median percentage change in the frequency of all partial-onset seizures per 28 days in the double-blind phase compared with baseline, while the primary endpoint for perampanel registration in the European Union was the 50% responder rate (percentage of patients who had a 50% or greater reduction in the frequency of all partial-onset seizures in the maintenance period relative to baseline). Safety was assessed by reporting use of concomitant medication, type of adverse events experienced during the trial, whether a patient withdrew from the study due to adverse events, clinical laboratory results, vital signs, EKG data, physical and neurologic examinations, and photosensitivity and withdrawal questionnaires.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

All studies were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice ICH-E6 Guideline CPMP/ICH/135/95, European Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC, and the US Code of Federal Regulations Part 21. Trial protocols, amendments, and informed consent were reviewed by national regulatory authorities in each country and independent ethics committees or institutional review boards for each site. All patients gave written informed consent before participation.

Analyses to assess time to prerandomization monthly seizure count.

Analyses were performed using the intent-to-treat populations of the 3 phase III trials, with outcomes reported according to randomized treatment.

The individualized prerandomization monthly seizure count was defined as the average number of seizures that each patient experienced per 28 days prerandomization. The endpoint of time to prerandomization monthly seizure count was defined, for each patient, as the number of days until the patient experienced a number of seizures equal to prerandomization monthly seizure count, or the end of the study for cases in which the prerandomization monthly seizure count was not reached. Patients who discontinued the study before reaching the endpoint were censored at the time of withdrawal.

Kaplan-Meier analyses were conducted to estimate the median time to prerandomization monthly seizure count and 95% confidence intervals for each treatment group, for all partial-onset seizures, SG seizures only, and CP + SG seizures. Analyses were conducted over 2 time periods: (1) from 2 weeks after the first dose, when patients had reached steady state for the minimally effective dose of 4 mg (referred to as the double-blind treatment phase analysis); and (2) from the start of the maintenance period, when patients had reached steady state for the highest dose of 12 mg (referred to as the maintenance period analysis).

The log-rank test was used to assess the significance of any differences in time to prerandomization monthly seizure count between the perampanel doses and placebo.

RESULTS

Patient demographics and the original efficacy endpoints for studies 304,10 305,11 and 306,14 including median percentage changes in seizure frequency and 50% responder rates, have been reported previously. The present analysis of time to prerandomization monthly seizure count included data from 378 patients who received placebo, perampanel 8 mg, or perampanel 12 mg for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in the double-blind treatment phase of study 304 (68 of these patients were censored); 374 patients who received placebo, perampanel 8 mg, or perampanel 12 mg in study 305 (56 patients censored); and 689 patients who received placebo, perampanel 2 mg, perampanel 4 mg, or perampanel 8 mg in study 306 (76 patients censored).

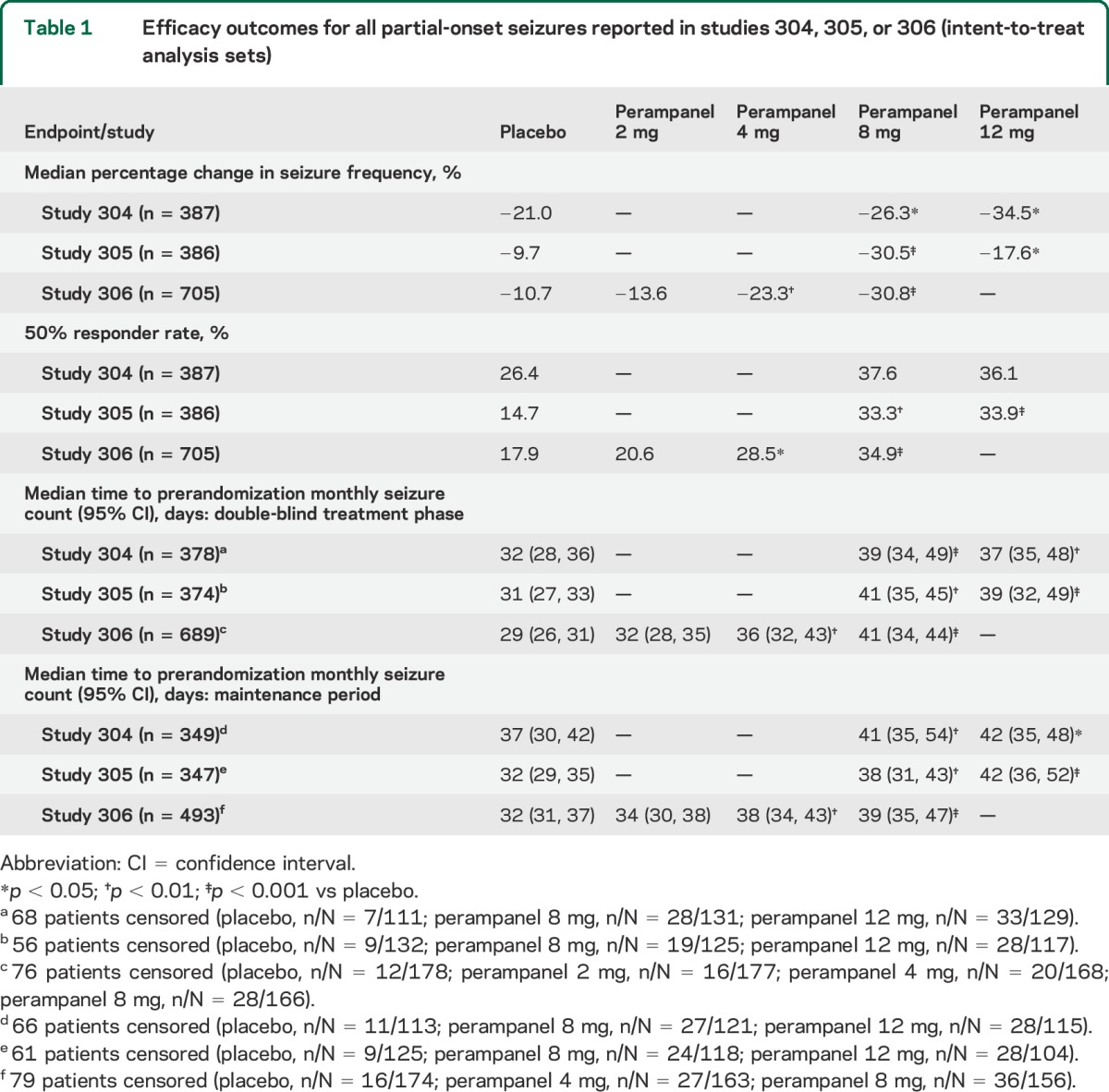

When all partial-onset seizures were included in the analysis, median time to prerandomization monthly seizure count for all partial-onset seizures was approximately 1 month in patients receiving placebo, as expected. With this seizure type, perampanel 4–12 mg significantly prolonged median time to prerandomization monthly seizure count by more than 1 week compared with placebo, over the double-blind treatment phase (from week 3) or the maintenance period, in all 3 studies (table 1). In contrast, the median time to prerandomization monthly seizure count with the noneffective dose of perampanel 2 mg was not significantly different from that achieved with placebo over the double-blind treatment phase of study 306. This was consistent with the effects of these perampanel doses indicated by the original efficacy endpoints of median percentage changes in seizure frequency and 50% responder rates.

Table 1.

Efficacy outcomes for all partial-onset seizures reported in studies 304, 305, or 306 (intent-to-treat analysis sets)

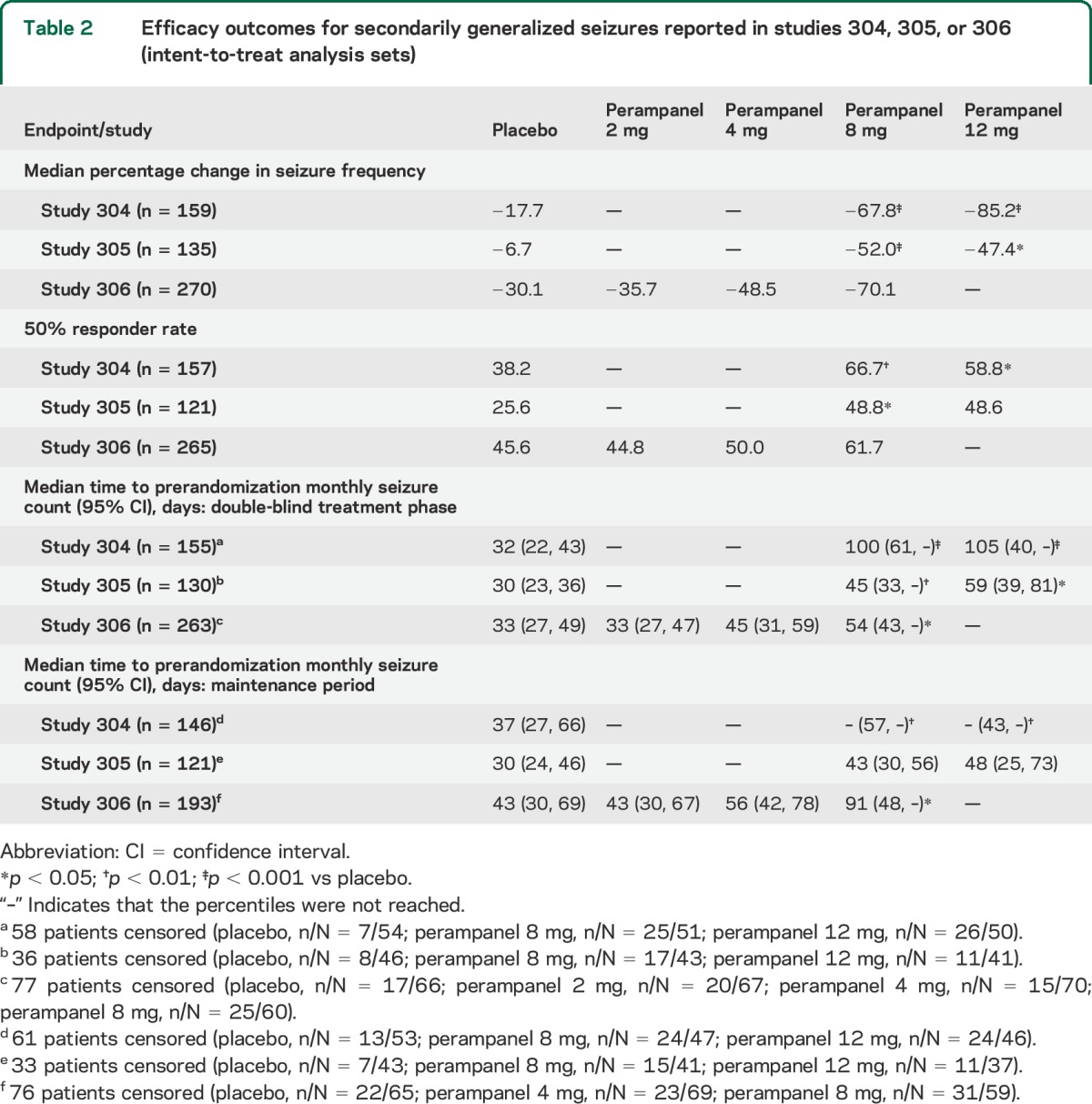

Analyses that included SG seizures only, or CP + SG seizures, also generally indicated a significantly prolonged median time to prerandomization monthly seizure count with perampanel 8–12 mg compared with placebo (table 2 and table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org). Outcomes at the 2 mg and 4 mg doses did not achieve statistical significance.

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes for secondarily generalized seizures reported in studies 304, 305, or 306 (intent-to-treat analysis sets)

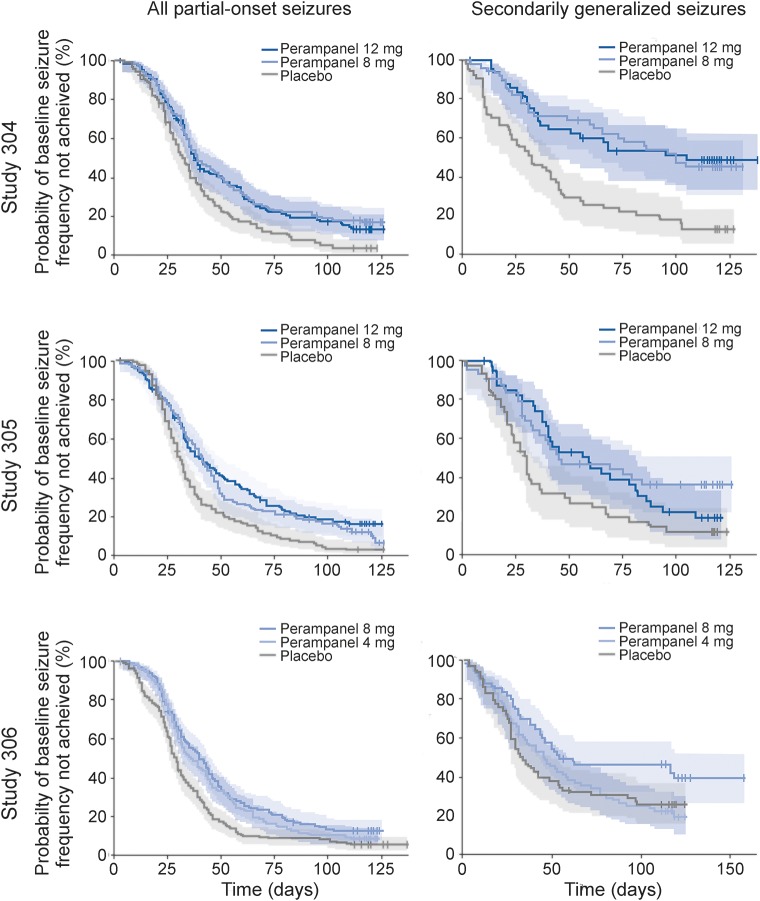

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to prerandomization monthly seizure count for all partial-onset seizures and SG seizures only, in the double-blind treatment phases (figure 2) or maintenance periods (figure e-1), of studies 304, 305, and 306, indicate the level of separation achieved among the treatment groups.

Figure 2. Probability of not achieving prerandomization monthly seizure count in the double-blind treatment phase.

Kaplan-Meier curves show probability, with 95% confidence limits (shading) and censored data points (vertical lines), for all partial-onset seizures and secondarily generalized seizures in the double-blind treatment phases of studies 304, 305, and 306.

DISCUSSION

The traditional design of phase III trials of novel add-on AEDs, involving a long placebo-controlled randomized treatment phase, was developed decades ago, when only a handful of AEDs were available, and when patients with epilepsy often failed on all acceptable treatment options. However, nowadays, with more than 20 AEDs available, it is becoming increasingly difficult to enroll patients in placebo-controlled trials. In addition, trials of AEDs do not typically include stopping rules, whereby patients would exit a trial if their epilepsy worsened or did not improve, and, therefore, poor outcomes may not be adequately addressed. Notably, a post hoc analysis of several trials of add-on treatments demonstrated that patients randomized to placebo are at an increased (by many fold) risk of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy compared with patients randomized to an active arm.18 Ultimately, it may no longer be reasonable to expect patients to accept the possibility of randomization to placebo for 3–4 months.

Time-to-event endpoints in trials of add-on AEDs are likely to reduce placebo exposure, reduce costs, and allow novel AEDs with therapeutic benefits to reach patients faster. This type of study design is not new to the epilepsy field,19,20 and has also been used in clinical trials investigating medications to control pain.21 The withdrawal to monotherapy design, which is used to obtain a monotherapy indication, uses a time-to-event outcome whereby patients reach an endpoint based on clinically important seizure worsening.22 A time to Nth seizure outcome has been proposed in the past,23 whereby N is set at an arbitrary number (e.g., 1, 3, or 10) and patients exit the trial if they experience this number of seizures. However, although post hoc analyses have suggested that this approach is able to correctly identify efficacious treatments and shorten patient exposure to placebo, the estimated sample sizes required to run such a trial are large. This is presumed to be a result of the fact that patients have variable seizure frequencies: typically, patients must have ≥3–4 seizures/month to enter these trials, but the range could include up to 100 seizures/month. Therefore, if N is set at a specific number, patients with high seizure frequencies would exit rapidly, often before there was a chance for improvement. In contrast, an endpoint to evaluate time to individualized prerandomization monthly seizure count may avoid this scenario, and enable the enrolment of patients who might otherwise be excluded due to a low baseline seizure frequency; this could help to address the selection bias of previous time to Nth seizure studies.

We analyzed data from 3 phase III trials of perampanel in order to explore the feasibility of time to individualized prerandomization monthly seizure count as a novel time-to-event endpoint for epilepsy trials. Compared with placebo, our analyses indicated that perampanel, at doses within the effective range of 4–12 mg, but not at the noneffective dose of 2 mg, significantly prolonged time to prerandomization monthly seizure count when all partial-onset seizures were included. This is a clinically relevant outcome, since it directly relates to a reduction in seizure frequency: as an example, for a patient whose typical seizure frequency is 4 seizures per month, a time of 2 months to reach the prerandomization monthly seizure count of 4 would mean that seizure incidence has been at least halved. Our findings are consistent with previously reported efficacy findings for the separate and pooled phase III data, which indicated that perampanel 4–12 mg increased median percentage reduction in seizure frequency and 50% responder rates compared with placebo.10,11,14,24 Overall, the novel time to prerandomization monthly seizure count approach appears to properly differentiate efficacious and nonefficacious therapies.

In the analysis of different seizure types, the improvements in time to prerandomization monthly seizure count with perampanel were observed for all seizure types, including in patients with more clinically severe SG seizures, which can be more objectively assessed. This is again consistent with previously reported efficacy findings for the pooled phase III data, which indicated that the greatest benefits to seizure frequency and 50% responder rates were observed in patients with SG seizures.24 However, improvements in time to prerandomization monthly seizure count with the perampanel 4 mg dose did not achieve statistical significance in patients with SG seizures only, or CP + SG seizures, suggesting that higher doses may be required in patients with these more severe seizure types. Nonetheless, it is particularly important to note that the perampanel 8 mg and 12 mg doses were associated with statistically significant improvements in time to prerandomization monthly seizure count in patients with SG seizures, despite the fact that only 38.2% of patients in our combined intent-to-treat analysis sets had SG seizures, and often at low frequency. This indicates that the new endpoint may have reasonable power, including for infrequently occurring seizures, since—for many standard endpoints—the low incidence of SG seizures often means that statistical significance is only achieved when data are pooled from several studies.

All 3 phase III trials used standard inclusion/exclusion criteria. Therefore, it is not possible to determine whether this trial design would still be successful if patients with different seizure characteristics had been enrolled (for example, clusters, longer interseizure intervals). In the future, performing post hoc analyses of other trials and modeling different characteristics would be useful for determining the robustness of this methodology.

The improvements in time to prerandomization monthly seizure count were seen whether patients were assessed over the maintenance period alone or over the whole double-blind treatment phase, from week 3, when patients had potentially reached steady-state plasma levels with the minimally effective dose of 4 mg. For future study designs, it will be necessary to establish a period of analysis in advance, which could be determined depending on the pharmacokinetic profile of the study drug, and the time required to reach an effective dose. It is anticipated that the methodology for future studies will be further informed by an ongoing study that is running simulations for patients according to their baseline seizure frequency. However, it is anticipated that future studies would maintain the current maximum duration of 3 months, and that the sample size would be similar to current trials in epilepsy.

If time to prerandomization monthly seizure count is accepted as a methodology going forward, it will be important to instruct clinicians on how to interpret the results in a clinically meaningful way. For example, if the median time to event is 3 months, it would mean that 50% of patients in the active arm continued in the study for 3 months. This could then be interpreted to state that 50% of patients had their seizure frequency reduced by at least two-thirds.

To integrate time to prerandomization monthly seizure count into the design of future studies, another important consideration would be the appropriate assessment of safety outcomes. The shorter duration of placebo administration that may be afforded by this novel endpoint will also lead to a shorter period for the collection of safety data in the control group. The implications of this, particularly with regard to the detection of adverse events that may be slower to emerge (for example, weight gain), should be considered, and extension studies would remain essential for the evaluation of long-term safety outcomes.

These data suggest that time to prerandomization monthly seizure count may be a potentially valuable new efficacy endpoint in clinical trials of novel AEDs, and warrant further examination by the epilepsy community and the regulatory agencies, as an alternative to traditional efficacy endpoints and study designs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank David Squillacote, formerly of Eisai Inc., for his review and input into the early stages of manuscript development, and Hannah FitzGibbon, of Complete Medical Communications, for technical editing of the manuscript and preparation of figures.

GLOSSARY

- AED

antiepileptic drug

- CP

complex partial

- SG

secondary generalized

Footnotes

Editorial, page 2010

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.A.F.: contributed to the design of the analyses and data interpretation, drafted the abstract and introduction sections of the manuscript, contributed to the discussion section, critically reviewed each draft of the manuscript, and accepts accountability for all aspects of the work. A.G.N.: contributed to the design of the analyses and data interpretation, drafted the discussion section of the manuscript, critically reviewed each draft of the manuscript, and accepts accountability for all aspects of the work. S.M.: contributed to the design of the analyses and data interpretation, drafted the methods section of the manuscript, critically reviewed each draft of the manuscript, and accepts accountability for all aspects of the work. L.K.: contributed to the design of the analyses and data interpretation, critically reviewed each draft of the manuscript, and accepts accountability for all aspects of the work. D.K.: contributed to the design and execution of the analyses and data interpretation, drafted the results section of the manuscript, critically reviewed each draft of the manuscript, and accepts accountability for all aspects of the work. E.B.: contributed to the design of the analyses and data interpretation, drafted the methods section of the manuscript, critically reviewed each draft of the manuscript, and accepts accountability for all aspects of the work.

STUDY FUNDING

Analyses and editorial support were funded by Eisai Inc.

DISCLOSURE

J. French is President of the Epilepsy Study Consortium and the NYU Comprehensive Epilepsy Center receives salary support from the consortium; has acted as a consultant for Accorda, GlaxoSmithKline, Impax, Johnson and Johnson, Marinus, Novartis, Pfizer, Sunovion, SK Life Sciences, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Upsher-Smith, and Vertex (all consulting is done on behalf of the Epilepsy Study Consortium, and fees are paid to the consortium); has participated in advisory boards for Accorda, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, SK Life Sciences, UCB, and Upsher-Smith; has been an investigator for clinical trials funded by Eisai, Novartis, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Upsher-Smith, Vertex, and LCGH; and has received grants from Eisai, Lundbeck, Pfizer, UCB, the Epilepsy Therapy Project, the Epilepsy Research Foundation, and the Epilepsy Study Consortium. A. Gil-Nagel has served on the speaker bureaus of Bial, Eisai, UCB, and ViroPharma, and has received an unrestricted grant from Bial. S. Malerba reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. L. Kramer is an employee of Eisai Inc. D. Kumar is an employee of Eisai Inc. E. Bagiella reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ben-Menachem E, Falter U. Efficacy and tolerability of levetiracetam 3000 mg/d in patients with refractory partial seizures: a multicenter, double-blind, responder-selected study evaluating monotherapy: European Levetiracetam Study Group. Epilepsia 2000;41:1276–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Menachem E, Biton V, Jatuzis D, Abou-Khalil B, Doty P, Rudd GD. Efficacy and safety of oral lacosamide as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia 2007;48:1308–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Menachem E, Gabbai AA, Hufnagel A, Maia J, Almeida L, Soares-da-Silva P. Eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive therapy in adult patients with partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2010;89:278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodie MJ, Duncan R, Vespignani H, Solyom A, Bitenskyy V, Lucas C. Dose-dependent safety and efficacy of zonisamide: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with refractory partial seizures. Epilepsia 2005;46:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodie MJ, Lerche H, Gil-Nagel A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive ezogabine (retigabine) in refractory partial epilepsy. Neurology 2010;75:1817–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cereghino JJ, Biton V, Abou-Khalil B, Dreifuss F, Gauer LJ, Leppik I. Levetiracetam for partial seizures: results of a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Neurology 2000;55:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung S, Sperling MR, Biton V, et al. Lacosamide as adjunctive therapy for partial-onset seizures: a randomized controlled trial. Epilepsia 2010;51:958–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elger C, Halasz P, Maia J, Almeida L, Soares-da-Silva P. Efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treatment in adults with refractory partial-onset seizures: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase III study. Epilepsia 2009;50:454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French JA, Abou-Khalil BW, Leroy RF, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ezogabine (retigabine) in partial epilepsy. Neurology 2011;76:1555–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.French JA, Krauss GL, Biton V, et al. Adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial-onset seizures: randomized phase III study 304. Neurology 2012;79:589–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French JA, Krauss GL, Steinhoff BJ, et al. Evaluation of adjunctive perampanel in patients with refractory partial-onset seizures: results of randomized global phase III study 305. Epilepsia 2013;54:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gil-Nagel A, Lopes-Lima J, Almeida L, Maia J, Soares-da-Silva P. Efficacy and safety of 800 and 1200 mg eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treatment in adults with refractory partial-onset seizures. Acta Neurol Scand 2009;120:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halász P, Kälviäinen R, Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska M, et al. Adjunctive lacosamide for partial-onset seizures: efficacy and safety results from a randomized controlled trial. Epilepsia 2009;50:443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krauss GL, Serratosa JM, Villanueva V, et al. Randomized phase III study 306: adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial-onset seizures. Neurology 2012;78:1408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter RJ, Partiot A, Sachdeo R, Nohria V, Alves WM. Randomized, multicenter, dose-ranging trial of retigabine for partial-onset seizures. Neurology 2007;68:1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sackellares JC, Ramsay RE, Wilder BJ, Browne TR, III, Shellenberger MK. Randomized, controlled clinical trial of zonisamide as adjunctive treatment for refractory partial seizures. Epilepsia 2004;45:610–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shorvon SD, Lowenthal A, Janz D, Bielen E, Loiseau P. Multicenter double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of levetiracetam as add-on therapy in patients with refractory partial seizures: European Levetiracetam Study Group. Epilepsia 2000;41:1179–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryvlin P, Cucherat M, Rheims S. Risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy in patients given adjunctive antiepileptic treatment for refractory seizures: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomised trials. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:961–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beydoun A, Sachdeo RC, Rosenfeld WE, et al. Oxcarbazepine monotherapy for partial-onset seizures: a multicenter, double-blind, clinical trial. Neurology 2000;54:2245–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pledger GW, Kramer LD. Clinical trials of investigational antiepileptic drugs: monotherapy designs. Epilepsia 1991;32:716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth SH. Efficacy and safety of tramadol HCl in breakthrough musculoskeletal pain attributed to osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1358–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.French JA, Temkin NR, Shneker BF, Hammer AE, Caldwell PT, Messenheimer JA. Lamotrigine XR conversion to monotherapy: first study using a historical control group. Neurotherapeutics 2012;9:176–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pledger GW, Sahlroot JT. Alternative analyses for antiepileptic drug trials. Epilepsy Res Suppl 1993;10:167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinhoff BJ, Ben-Menachem E, Ryvlin P, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive perampanel for the treatment of refractory partial seizures: a pooled analysis of three phase III studies. Epilepsia 2013;54:1481–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.