Abstract

Background: Pregnancy is associated with weight gain. Moreover, overweight and obese women subsequently have difficulties with breastfeeding. Both of these factors may contribute to the observed relations between reproduction and weight problems.

Objective: In this study we evaluated the combined effects of maternal prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) and gestational weight gain (GWG) on the ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding in a large, population-based study, the MoBa (Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study).

Methods: Initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum in relation to prepregnancy BMI and GWG were evaluated among 49,669 women with complete information on BMI, GWG, and breastfeeding by using multivariable logistic regression analyses.

Results: An excess risk of unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding was observed among all categories of prepregnant overweight and obese women as well as among most GWG categories of prepregnant underweight women. For all of these groups, risks of unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding were significantly higher with GWG below recommendations. The same patterns were seen among all categories of prepregnant overweight and obese women with respect to risks of inability to sustain full or any breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum. However, prepregnant obese women had the highest risk of inability to sustain full or any breastfeeding if they had also experienced GWG above recommendations. The associations between prepregnancy BMI and breastfeeding were modified by Apgar scores and maternal asthma.

Conclusions: The results show the importance of encouraging women to start pregnancy with a healthy BMI as well as to have GWG within recommendations for the benefit of successful breastfeeding. The interactions with medical conditions further highlight the complexity of the associations.

Keywords: prepregnant, body mass index, gestational weight gain, breastfeeding, medical conditions, MoBa, The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study

Introduction

The epidemic of obesity has already had major health consequences worldwide. Comorbidities of overweight and obesity have been clearly shown in mid- and late life when cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes typically emerge. Moreover, increasing rates of cardiovascular disease are currently being documented in early adulthood, and type 2 diabetes can now be observed in children. Both of these phenomena may be partly explained by obesity in younger populations (1).

Thus, it is increasingly recognized that obesity has implications across the life span. One health effect of obesity that has received relatively less attention is its impact on the mother’s ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding (2, 3). This could have immediate health consequences for the mother herself, whose body weight renormalization process may be compromised if lactation is not successful (4), which may further lead to long-term health consequences. Recent results from the Norwegian Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT) study showed significant inverse associations between lifetime duration of lactation and BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, serum lipids, and cardiovascular mortality (5, 6). There are also possible adverse effects on the child’s health of shorter breastfeeding including, among others, increased risk of the child developing diabetes (7, 8) and obesity (9–11).

Previous reviews of human studies showed associations between obesity and reduced ability to initiate breastfeeding (2, 12, 13). Less is known about whether obesity can also impair sustained lactation during the rapid growth of the child. Given the large fraction of women who do not fulfill WHO recommendations of 6 mo exclusive breastfeeding, it is of interest to understand whether maternal weight status may contribute to this association. In addition, it is not understood whether the effect of obesity on lactation performance may be modified by other medical conditions before, during, and after pregnancy (2).

Recommendations for maternal weight gain during pregnancy differ for different categories of BMI, with lower weight gain recommended for women who are overweight and obese (14). Still, the role of gestational weight gain (GWG)8 in breastfeeding initiation and maintenance is not clear (2, 3, 15, 16). The purpose of this study is to address these questions in a sufficiently large, population-based cohort of women followed from pregnancy to postpartum periods. Specifically, we aimed to examine the interrelations between maternal prepregnancy BMI and GWG on breastfeeding initiation and duration, in the context of other medical and sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

Study cohort and study design.

The women included in the present analyses are part of the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa), a prospective, population-based pregnancy cohort study initiated and conducted by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (17, 18). The MoBa study was planned to broadly evaluate associations between exposures and diseases for the sake of future prevention; hence, data are collected on multiple exposures and multiple health outcomes.

Between 1999 and 2008, women from throughout Norway were invited to take part in the study by postal invitation at the time of the routine ultrasound examination that is offered to all pregnant women in the country (17). In total, 40.6% of the invited women consented to participate, and the cohort today includes 114,500 children born to 95,200 mothers. Thus, many women participated in MoBa with >1 child. The cohort also includes 75,200 fathers.

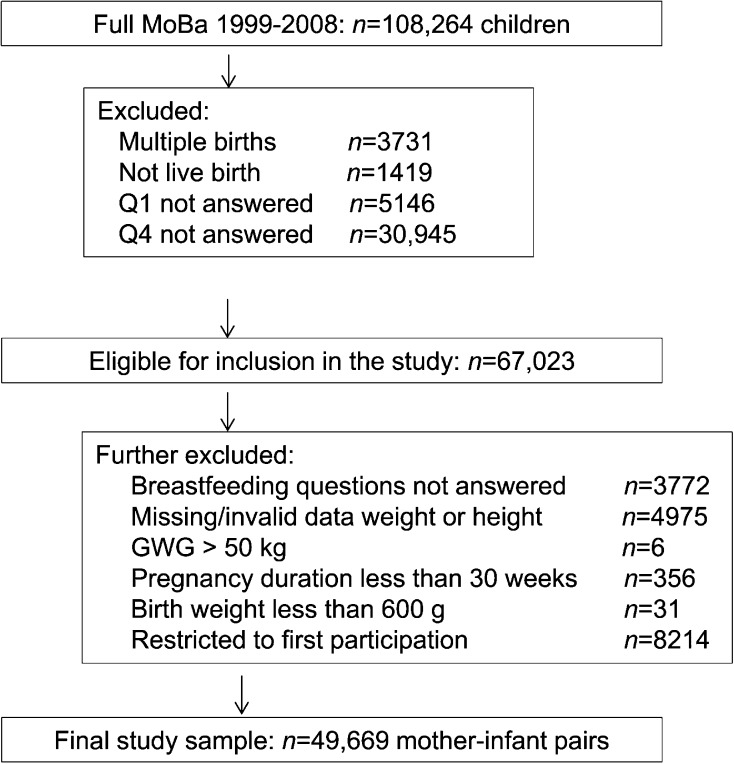

The sample selected for the present analyses has previously been described in detail (4). Briefly, all 67,023 women in the MoBa cohort who had delivered a singleton live-birth infant and who had information available in the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN) (19) as well as from the MoBa questionnaires 1 and 4 were included (Figure 1; see further details below). Thereafter, women who had not answered the specific questions about body weight, height, or breastfeeding or who had invalid data on GWG, infant birth weight <600 g, or pregnancy duration <30 wk were excluded. Among women who had participated with >1 pregnancy, only their first pregnancies were included. The final sample available for analyses at 4 and 6 mo postpartum included 49,669 women. The 17,348 pregnancies excluded in the second step and the 49,669 women included in the analyses were compared on background characteristics. Most differences were significant, which is probably a reflection of large sample sizes. Important differences included a higher proportion of primipara women and a higher proportion of cohabitating rather than married women in the included study sample. These differences are likely explained by the exclusion of second pregnancies in the same participants. Only negligible differences between the samples were found with respect to maternal age, education, smoking during pregnancy, physical exercise before and after pregnancy, and household income.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart showing the selection of MoBa study participants. GWG, gestational weight gain; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study; Q, questionnaire.

All participating women provided informed consent at recruitment. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics in southeastern Norway. The current analyses used version 5 of the quality-assured data files released for research in 2010 by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Measurements.

Three self-administered questionnaires were sent out during pregnancy (questionnaire 1 in weeks 13–17, questionnaire 2 in weeks 17–22, and questionnaire 3 in week 30) and a fourth questionnaire (questionnaire 4) was sent at 6 mo postpartum. In this study we used information from questionnaires 1 and 4. Questionnaire 1 contained questions about prepregnancy weight, medical history, medications, occupation, income, and lifestyle habits. Questionnaire 4 included questions about maternal and infant health and maternal lifestyle. English translations of the questionnaires can be found on the MoBa website (20). Pregnancy and birth records from the MBRN are linked with the MoBa database.

The outcome measures in this study were ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding, which originate from questionnaire 4 administered at 6 mo postpartum. The 3 questionnaire items used in this analysis described infant feeding during the first week after birth; the kinds of liquids that the infant received at months 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6; and in which month the mother started giving complementary food to the child.

In the analyses presented here, “not initiating breastfeeding” is defined as no breastfeeding at all. Among those who initiated breastfeeding, the ability to sustain full or any breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum was evaluated. Because the WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding until 6 mo postpartum (21), analyses of MoBa data on full breastfeeding for 6 mo postpartum were considered relevant. However, only 13.7% of MoBa mothers who initiated breastfeeding reported full breastfeeding for 6 mo postpartum, compared with 59.1% who exhibited full breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum. Hence, results at 4 mo postpartum may yield additional information and are also presented.

We use the definition of full breastfeeding as described by WHO (22), which precludes any use of infant formula, other milk, or solid food. We were unable to define exclusive breastfeeding, because beyond the first week of life, not all versions of the questionnaire included questions on use of water, water-based drinks, and fruit juice (23). Any breastfeeding at all is defined as breastfeeding in combination with infant formula, other milk, and/or solid food.

The exposure variables included prepregnancy BMI and GWG. Prepregnant weight and height were self-reported in weeks 13–17 (questionnaire 1). BMI was expressed as weight/height square (kg/m2) and was classified into underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9), and obese grades I (30.0–34.9), II (35.0 – 39.9), and III (≥40.0) according to WHO classifications (24). Furthermore, GWG was calculated as the difference between weight at delivery reported at 6 mo postpartum (questionnaire 4) and prepregnant weight reported in questionnaire 1. Finally, the combined effects of both these exposures on breastfeeding success were evaluated by the construction of a composite variable. Within each BMI category, women were divided into those who experienced a GWG within, below, or above that recommended by the US Institute of Medicine (IoM), respectively (14). Here, for women with a prepregnancy BMI <18.5, the recommended GWG is 12.5–18.0 kg; for a BMI of 18.5–24.0 the recommended GWG is 11.5–16.0 kg; for a BMI of 25.0–29.9 the recommended GWG is 7.0–11.5 kg, and for a BMI ≥30.0 the recommended GWG is 5.0–9.0 kg.

Additional variables were included as covariates. Maternal age at delivery was used as a continuous variable except for descriptive statistics. Maternal education was categorized into <12, 12, 13–16, and ≥17 y. Household income was expressed as the combination of the woman’s and her partner’s income and classified into both incomes <300,000 Norwegian crowns (NOK), one income ≥300,000 NOK, or both incomes ≥300,000 NOK. Marital status was classified as married, cohabitating, single, or widow. Smoking before pregnancy was defined as none, occasional, and daily. Smoking during early pregnancy was defined as none, occasional, and daily and refers to behavior in the first trimester. Exercise at different time points in relation to pregnancy was based on questions on 13 types of recreational exercise and categorized into no exercise, less than weekly, 1–2 times/wk, or ≥3 times/wk. Information from the MBRN was used to identify medical conditions including asthma, diabetes, hypertension before and/or during pregnancy, preeclampsia during pregnancy, and cesarean delivery as well as infant Apgar score at 1 and 5 min. The preeclampsia diagnosis of MBRN was recently validated and found to be of high quality (25).

Statistical analyses.

Differences between included and excluded women were tested with Student’s t test and chi-square tests. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate relations between the ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding and categorical background variables. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to study the associations between prepregnancy BMI and GWG, and ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding. To adjust for potential confounding, maternal education, household income, maternal age, parity, smoking, cesarean delivery, and diabetes were included in multivariable regression analyses. The selection of potential confounding variables was based on previous work in evaluating the relation between breastfeeding and maternal weight (4).

Significant interactions between prepregnancy BMI and GWG, in their effects on sustaining full and any breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum, were found (P-interaction < 0.001). A suggestive interaction was observed for failure to initiate breastfeeding (P-interaction = 0.07). Therefore, the combined effects of both of these exposures on breastfeeding success were evaluated by the construction of a composite variable (see above). The category comprising normal-weight women (BMI of 18.5–24.9) and GWG according to the IoM recommendation (11.5 – 16.0 kg) was used as the reference category.

Modifying effects of medical conditions before, during, and after pregnancy on the effect of maternal obesity on lactation performance were evaluated in multivariable regression analyses. Conditions evaluated included asthma, diabetes, rheumatism, hypertension before and/or during pregnancy, preeclampsia during pregnancy, and cesarean delivery as well as infant Apgar score at 1 and 5 min. Lactation performance was evaluated as the ability to initiate as well as to sustain full and any breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum.

The significance level was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed in SPSS, version 22.0 (IBM).

Results

Background characteristics of the included women, in relation to their ability to initiate breastfeeding as well as to sustain full or any breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum, are shown in Table 1. Partly due to the large sample size, the breastfeeding outcomes differed significantly in relation to almost all background characteristics evaluated. An important result was the lower proportion of women who initiated breastfeeding among those who had a prepregnancy BMI ≥35.0. Lower proportions of full or any breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum were associated with low maternal age, low maternal education, low household income, being single or widow, high prepregnancy BMI, high pregnancy weight gain, smoking daily during early pregnancy, and no exercise before, during, or after pregnancy.

TABLE 1.

Background characteristics of the 49,669 Norwegian women in the MoBa sample by breastfeeding pattern1

| Total sample, % | Initiated breastfeeding, % | Sustained full breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum,2 % | Sustained any breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum,2 % | Sustained full breastfeeding for 6 mo postpartum,2 % | Sustained any breastfeeding for 6 mo postpartum,2 % | |

| All women | 100 | 99.3 | 59.1 | 88.1 | 13.7 | 80.6 |

| Maternal age (y) | ||||||

| ≤19 | 0.9 | 98.0* | 32.3* | 58.5* | 3.8* | 49.4* |

| 20–24 | 10.6 | 99.3 | 48.3 | 77.8 | 7.1 | 66.2 |

| 25–29 | 34.5 | 99.4 | 58.4 | 88.1 | 11.3 | 80.3 |

| 30–34 | 37.5 | 99.3 | 61.8 | 90.8 | 15.6 | 84.4 |

| 35–39 | 14.5 | 99.1 | 63.0 | 90.4 | 18.8 | 83.6 |

| ≥40 | 2.0 | 98.6 | 61.1 | 88.1 | 19.8 | 81.8 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 0 | 54.0 | 99.3 | 53.4* | 86.8* | 11.0* | 79.2* |

| 1 | 29.3 | 99.2 | 64.3 | 89.2 | 14.6 | 81.3 |

| 2 | 13.1 | 99.1 | 68.6 | 90.8 | 19.1 | 84.5 |

| 3 | 2.8 | 99.3 | 68.9 | 89.0 | 25.2 | 81.9 |

| ≥4 | 0.8 | 99.0 | 65.2 | 86.6 | 24.2 | 78.1 |

| Maternal education (y) | ||||||

| <12 | 6.2 | 98.3* | 45.6* | 70.8* | 8.7* | 59.4* |

| 12 | 24.7 | 98.9 | 52.2 | 80.5 | 9.6 | 69.7 |

| 13–16 | 42.7 | 99.5 | 61.5 | 91.2 | 14.2 | 84.5 |

| ≥17 | 24.4 | 99.6 | 65.4 | 94.7 | 18.2 | 90.2 |

| Other and missing | 2.0 | 98.8 | 57.3 | 86.2 | 11.7 | 78.3 |

| Household income, NOK/y | ||||||

| Both incomes <300,000 | 29.5 | 99.1* | 55.6* | 83.8* | 11.5* | 75.1* |

| One income ≥300,000 | 41.8 | 99.3 | 59.7 | 88.5 | 14.0 | 80.8 |

| Both incomes ≥300,000 | 26.2 | 99.5 | 62.5 | 92.7 | 15.5 | 87.0 |

| Missing | 2.6 | 98.3 | 55.0 | 82.4 | 14.0 | 73.8 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 46.0 | 99.3** | 63.6* | 91.0* | 16.5* | 84.5* |

| Cohabitating | 50.2 | 99.3 | 56.0 | 86.2 | 11.4 | 77.9 |

| Single/widow | 2.2 | 98.6 | 45.0 | 75.3 | 9.8 | 66.2 |

| Other or not known | 1.5 | 98.9 | 48.7 | 80.1 | 9.4 | 71.6 |

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 3.0 | 99.0* | 57.8* | 85.1* | 14.2* | 77.0* |

| 18.5–24.9 | 65.9 | 99.6 | 62.9 | 90.6 | 14.8 | 83.8 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 21.8 | 98.8 | 54.4 | 85.7 | 11.6 | 77.4 |

| 30.0–34.9 | 6.8 | 98.7 | 45.4 | 77.9 | 10.3 | 68.4 |

| ≥35.0 | 2.4 | 97.4 | 37.8 | 71.3 | 8.9 | 58.7 |

| Pregnancy weight gain (kg) | ||||||

| <10 | 15.5 | 98.8* | 56.7* | 86.3* | 14.1* | 78.8* |

| 10–15 | 41.6 | 99.4 | 61.9 | 89.9 | 15.0 | 83.2 |

| 16–19 | 22.7 | 99.4 | 61.0 | 89.5 | 13.7 | 82.3 |

| ≥20 | 20.2 | 99.2 | 53.2 | 84.0 | 10.6 | 74.5 |

| Smoking in early pregnancy | ||||||

| None | 91.3 | 99.3* | 60.6* | 89.7* | 14.4* | 82.7* |

| Occasionally | 2.7 | 99.3 | 47.0 | 74.9 | 6.5 | 63.5 |

| Daily | 5.3 | 98.0 | 39.3 | 67.6 | 4.8 | 53.1 |

| Missing | 0.7 | 98.8 | 55.5 | 81.7 | 11.3 | 71.3 |

| Exercise in last 3 mo before pregnancy | ||||||

| None | 5.7 | 98.6* | 50.0* | 79.7* | 9.8* | 69.9* |

| Less than weekly | 13.8 | 99.0 | 55.3 | 84.7 | 11.7 | 75.8 |

| 1–2 times/wk | 28.6 | 99.4 | 59.8 | 88.6 | 13.5 | 81.3 |

| ≥3 times/wk | 48.6 | 99.4 | 61.2 | 90.1 | 14.8 | 83.3 |

| Missing | 3.2 | 98.3 | 54.8 | 81.3 | 12.6 | 72.0 |

| Exercise in early pregnancy | ||||||

| None | 14.0 | 98.8* | 52.7* | 82.6* | 10.8* | 73.3* |

| Less than weekly | 19.8 | 99.3 | 57.4 | 87.2 | 13.0 | 79.2 |

| 1–2 times/wk | 29.9 | 99.5 | 60.5 | 89.2 | 13.9 | 82.3 |

| ≥3 times/wk | 28.6 | 99.5 | 62.6 | 91.2 | 15.4 | 84.8 |

| Missing | 7.6 | 98.4 | 56.7 | 83.9 | 13.1 | 74.5 |

| Exercise in 6 mo postpartum | ||||||

| None | 8.9 | 98.6* | 52.1* | 82.1* | 11.5* | 73.2* |

| Less than weekly | 10.5 | 99.1 | 57.5 | 86.6 | 12.4 | 78.5 |

| 1–2 times/wk | 26.9 | 99.4 | 59.5 | 88.2 | 13.7 | 80.9 |

| ≥3 times/wk | 53.0 | 99.4 | 60.5 | 89.3 | 14.2 | 82.1 |

| Missing | 0.6 | 98.9 | 51.8 | 82.0 | 14.7 | 74.1 |

Categories differ from one another (chi-square test): *P < 0.001, **P < 0.05. MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study; NOK, Norwegian crowns.

Among the 49,309 women who initiated breastfeeding.

The women’s ability to initiate breastfeeding as well as to sustain full or any breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum differed significantly in relation to categories based on the combination of prepregnancy BMI and GWG (Tables 2–4). In multivariable analyses, adjusting for maternal age, parity, education, smoking, household income, and maternal experiences of diabetes or cesarean delivery, significantly higher risks of unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding were seen among most GWG categories of prepregnant underweight women and all GWG categories of overweight and obese women, compared with normal-weight women who gained within the IoM guidelines (Table 2). Among the obese women, the highest risks were found among those with a prepregnancy BMI >40 (data not shown). Furthermore, in multivariate analyses, risks of unsuccessful initiation were even higher with GWG below recommendations. The same patterns were also seen among all categories of prepregnant overweight and obese women with respect to risks of inability to sustain full or any breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum among those who initiated breastfeeding (Tables 3 and 4). The only exception to the pattern was that, for full breastfeeding, the risk increases with GWG below recommendations were no longer significant among underweight and normal-weight women. In addition, for 4 and 6 mo postpartum, women who were obese prepregnancy had the highest risk of inability to sustain full or any breastfeeding if they had also experienced GWG above recommendations.

TABLE 2.

Predicting unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding among the Norwegian women in the MoBa study1

| OR (95% CI) |

|||

| Prepregnancy BMI and GWG group2 | n | Crude model | Adjusted model3 |

| Normal | |||

| Within recommendations | 13,009 | 1 | 1 |

| Below recommendations | 7087 | 1.12 (0.71, 1.75) | 1.09 (0.70, 1.70) |

| Above recommendations | 12,653 | 1.29 (0.89, 1.87) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.60) |

| Underweight | |||

| Within recommendations | 657 | 1.16 (0.36, 3.74) | 1.07 (0.33, 3.44) |

| Below recommendations | 446 | 3.46 (1.48, 8.12) | 3.25 (1.38, 7.65) |

| Above recommendations | 365 | 4.25 (1.81, 9.96) | 2.96 (1.25, 7.02) |

| Overweight | |||

| Within recommendations | 2285 | 3.49 (2.23, 5.47) | 2.86 (1.82, 4.49) |

| Below recommendations | 970 | 4.26 (2.42, 7.50) | 3.25 (1.84, 5.76) |

| Above recommendations | 7598 | 2.77 (1.95, 3.94) | 2.22 (1.56, 3.16) |

| Obese | |||

| Within recommendations | 971 | 4.80 (2.79, 8.25) | 3.14 (1.81, 5.43) |

| Below recommendations | 826 | 5.98 (3.52, 10.18) | 3.89 (2.26, 6.70) |

| Above recommendations | 2082 | 3.59 (2.36, 5.45) | 2.38 (1.55, 3.64) |

n = 49,669. GWG, gestational weight gain; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study.

Prepregnancy BMI was categorized as normal, underweight, overweight, or obese grades I–III according to WHO classifications and GWG was expressed as within, below, or above the GWG recommended by the Institute of Medicine (11). The latter recommendation takes prepregnancy BMI into account.

Adjusted for income, education, age, smoking, parity, diabetes, and cesarean delivery.

TABLE 4.

Predicting inability to breastfeed at all for 4 and 6 mo postpartum among the Norwegian women in the MoBa study1

| 4 mo postpartum, OR (95% CI) |

6 mo postpartum, OR (95% CI) |

||||

| Prepregnancy BMI and GWG group2 | n | Crude model | Adjusted model3 | Crude model | Adjusted model3 |

| Normal | |||||

| Within recommendations | 12,958 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Below recommendations | 7056 | 1.08 (0.98, 1.20) | 1.07 (0.96, 1.19) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.16) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.15) |

| Above recommendations | 12,589 | 1.46 (1.34, 1.59) | 1.12 (1.03, 1.22) | 1.40 (1.32, 1.50) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.18) |

| Underweight | |||||

| Within recommendations | 654 | 1.80 (1.42, 2.27) | 1.32 (1.04, 1.69) | 1.66 (1.37, 2.01) | 1.26 (1.03, 1.54) |

| Below recommendations | 440 | 1.48 (1.10, 2.00) | 1.24 (0.91, 1.70) | 1.32 (1.03, 1.69) | 1.14 (0.88, 1.48) |

| Above recommendations | 359 | 3.15 (2.43, 4.09) | 1.54 (1.18, 2.04) | 2.77 (2.20, 3.48) | 1.43 (1.12, 1.82) |

| Overweight | |||||

| Within recommendations | 2254 | 1.77 (1.54, 2.02) | 1.56 (1.36, 1.80) | 1.60 (1.43, 1.79) | 1.43 (1.27, 1.60) |

| Below recommendations | 954 | 2.20 (1.83, 2.65) | 1.82 (1.50, 2.20) | 1.87 (1.60, 2.19) | 1.57 (1.33, 1.84) |

| Above recommendations | 7516 | 1.94 (1.77, 2.12) | 1.52 (1.39, 1.67) | 1.79 (1.66, 1.93) | 1.43 (1.33, 1.55) |

| Obese | |||||

| Within recommendations | 953 | 3.12 (2.64, 3.69) | 2.26 (1.89, 2.69) | 2.56 (2.21, 2.97) | 1.90 (1.63, 2.22) |

| Below recommendations | 807 | 3.83 (3.22, 4.55) | 2.90 (2.42, 3.48) | 2.98 (2.56, 3.48) | 2.30 (1.96, 2.71) |

| Above recommendations | 2763 | 3.72 (3.43, 4.15) | 2.51 (2.24, 2.81) | 3.37 (3.08, 3.70) | 2.38 (2.16, 2.62) |

Among those who initiated breastfeeding, n = 49,309. GWG, gestational weight gain; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study.

Prepregnancy BMI was categorized as normal, underweight, overweight, or obese grades I–III according to WHO classifications, and GWG was expressed as within, below, or above the GWG recommended by the Institute of Medicine (11). The latter recommendation takes prepregnancy BMI into account.

Adjusted for income, education, age, smoking, parity, diabetes, and cesarean delivery.

TABLE 3.

Predicting inability to fully breastfeed for 4 and 6 mo postpartum among the Norwegian women in the MoBa study1

| 4 mo postpartum, OR (95% CI) |

6 mo postpartum, OR (95% CI) |

||||

| Prepregnancy BMI and GWG group2 | n | Crude model | Adjusted model3 | Crude model | Adjusted model3 |

| Normal | |||||

| Within recommendations | 12,958 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Below recommendations | 7056 | 1.10 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.16) | 1.02 (0.94,1.11) | 1.02 (0.94, 1.10) |

| Above recommendations | 12,589 | 1.22 (1.16, 1.29) | 1.08 (1.02, 1.13) | 1.25 (1.16, 1.34) | 1.08 (1.01, 1.16) |

| Underweight | |||||

| Within recommendations | 654 | 1.35 (1.15, 1.58) | 1.19 (1.01, 1.40) | 1.13 (0.90, 1.41) | 0.94 (0.75, 1.18) |

| Below recommendations | 440 | 1.20 (0.99, 1.46) | 1.12 (0.92, 1.37) | 0.85 (0.67, 1.09) | 0.78 (0.61, 1.00) |

| Above recommendations | 359 | 1.61 (1.30, 1.98) | 1.15 (0.92, 1.42) | 1.87 (1.31, 2.69) | 1.21 (0.84, 1.74) |

| Overweight | |||||

| Within recommendations | 2254 | 1.45 (1.32, 1.59) | 1.42 (1.29, 1.56) | 1.31 (1.14, 1.49) | 1.29 (1.12, 1.47) |

| Below recommendations | 954 | 1.52 (1.33, 1.74) | 1.46 (1.28, 1.68) | 1.18 (0.98, 1.43) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.38) |

| Above recommendations | 7516 | 1.61 (1.52, 1.70) | 1.44 (1.36, 1.53) | 1.53 (1.40, 1.67) | 1.36 (1.24, 1.48) |

| Obese | |||||

| Within recommendations | 953 | 1.91 (1.67, 2.18) | 1.67 (1.45, 1.91) | 1.50 (1.22,1.84) | 1.33 (1.08, 1.64) |

| Below recommendations | 807 | 2.15 (1.87, 2.48) | 1.97 (1.70, 2.28) | 1.57 (1.25, 1.97) | 1.48 (1.17, 1.86) |

| Above recommendations | 2763 | 2.75 (2.53, 2.99) | 2.27 (2.08, 2.48) | 1.86 (1.62, 2.13) | 1.50 (1.31, 1.73) |

Among those who initiated breastfeeding, n = 49,309. GWG, gestational weight gain; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study.

Prepregnant BMI was categorized as normal, underweight, overweight, or obese grades I–III according to WHO classifications, and GWG was expressed as within, below, or above the GWG recommended by the Institute of Medicine (11). The latter recommendation takes prepregnancy BMI into account.

Adjusted for income, education, age, smoking, parity, diabetes, and cesarean delivery.

Modifying effects of medical conditions before and during pregnancy were shown on the effect of maternal obesity on ability to sustain breastfeeding at 4 mo postpartum. Significant interactions included infant Apgar score at 1 and 5 min on the ability to sustain full breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum (P-interaction = 0.02 for both) and asthma on the ability to sustain any breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum (P-interaction = 0.03). The associations between maternal prepregnant BMI categories on lactation outcomes at 4 mo postpartum, stratified by these medical conditions, are shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. The degree of prepregnant obesity was a stronger risk factor for inability to sustain full breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum among mothers of infants with a normal Apgar score at 1 and 5 min than among mothers of infants with low Apgar score at 1 and 5 min. Furthermore, the degree of prepregnant obesity was a stronger risk factor for inability to sustain any breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum among women without asthma than among women with asthma. No such modification was found with respect to ability to initiate or to sustain breastfeeding for 6 mo postpartum.

Discussion

In this large, population-based cohort study we were able to evaluate the combined effects of maternal prepregnancy BMI and GWG on the mother’s later ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding, taking known medical and sociodemographic confounders into account. Significantly higher risks of unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding were seen among most GWG categories of prepregnant underweight women and all GWG categories of prepregnant overweight and obese women. Risks of unsuccessful initiation were even higher with higher grades of prepregnant obesity as well as with GWG below recommendations. The same patterns were also seen among all categories of prepregnant overweight and obese women with respect to risks of inability to sustain full or any breastfeeding for 4 and 6 mo postpartum. However, prepregnant obese women had the highest risk of inability to sustain full or any breastfeeding if they had also experienced GWG above recommendations. These results show the importance of preventing overweight in women of reproductive age and supporting them to gain weight within recommendations during pregnancy, so that they may achieve recommended breastfeeding patterns. Shorter breastfeeding duration will have long-term consequences for the woman’s body weight and metabolic health (5, 6, 26) as well as for the health of her offspring (7–11). It is thus important to break this vicious circle.

Furthermore, the degree of prepregnant obesity was a stronger risk factor for inability to sustain full breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum among mothers of infants with a normal Apgar score at 1 and 5 min than among mothers of infants with a low Apgar score at 1 and 5 min. In addition, the degree of prepregnant obesity was a stronger risk factor for inability to sustain any breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum among women without asthma than among women with asthma. Perhaps the associations between prepregnant obesity and breastfeeding ability become more prominent in the absence of other medical complications, or they may simply be chance findings. Overall, these interactions with medical conditions further highlight the complexity of the associations studied and may help explain earlier contradictory findings.

A main strength of this study is the large sample size of MoBa, which allows for evaluations of complex interactions (i.e., the combined effects of prepregnancy BMI and GWG as well as of prepregnancy BMI and medical conditions on breastfeeding initiation and sustenance). Few earlier studies have been able to evaluate these interactions with sufficient power. Another strength of the study is its population-based sampling, meaning that the study sample represents most childbearing women in Norway. Potential bias due to self-selection in MoBa has been evaluated by using data from the population-based MBRN (18). Differences in prevalence estimates were found between women participating in MoBa and all pregnant women, indicating that nonparticipating women were younger, had less education, more often lived alone, more often smoked, and more often were overweight or obese. However, no significant differences were found in assessments of 8 associations between prenatal or pregnancy exposures and reproductive outcomes. Thus, the associations found in our study are likely to represent those of most childbearing women in Norway and in similar contexts.

Almost all of the women in MoBa initiated breastfeeding (99.3%), which is a high proportion in international comparisons. For example, one of the US Healthy People 2020 goals is that 81.9% of newborns should ever be breastfed (27) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s report from 2013 revealed the proportion to be 76.5%, ranging from 50.5% in Mississippi to 91.8% in Idaho (28). Almost two-thirds of the women who had initiated breastfeeding sustained full breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum, but only 14% did so for 6 mo postpartum. However, 88% reported any breastfeeding for 4 mo postpartum and 80% did so for 6 mo postpartum. Hence, most Norwegian women continue to breastfeed their children during the first half year, but few practice full breastfeeding beyond 4 mo postpartum, which is in line with a recent national study (29).

Wojcicki (2) evaluated associations between maternal prepregnancy BMI and ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding. Among the 13 articles found in PubMed, 9 presented significant negative effects of maternal prepregnant overweight and obesity on ability to initiate breastfeeding. These results support our findings that higher prepregnancy BMI classes constitute a risk of unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding. Possible mechanisms include difficulties in putting the infant to the breast, lower production of prolactin in response to suckling in the first week postpartum, delayed lactogenesis stage II, and psychosocial factors (16).

Only a few of these studies were able to model interactions between prepregnancy BMI and GWG on ability to initiate breastfeeding. Li et al. (15) evaluated data on 51,329 low-income women in the US Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System and the Pregnancy Nutrition Surveillance System. Significantly higher risks of unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding were found among women who were underweight before pregnancy and with GWG below the IoM recommendations, which corresponds to our findings. However, in contrast to our findings, Li et al. did not find any significantly higher risks among women who were underweight before pregnancy and with GWG higher than the IoM recommendations. Also similar to our findings, Li et al. reported significantly higher risks of unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding among women with prepregnancy overweight or obesity and all categories of GWG. However, the ORs for the American women were in the ranges of 1.10 to 1.25, whereas our ORs for the Norwegian women were in the range of 2.22 to 3.89. Perhaps the different effect sizes reflect the more recent data in the Norwegian sample (1999–2008) than in the American sample (1996), where additional metabolic and/or social changes related to the evolving obesogenic environments have developed, or the population-based sample of Norwegian mothers compared with the more homogeneous sample of low-income American women.

Hilson et al. (16) evaluated information on 2783 American women who gave birth between 1988 and 1997, and who all initiated breastfeeding. In analyses of women who were unable to sustain breastfeeding for 4 d, significantly higher odds of failure were found among women with a normal BMI (OR: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.05, 2.63) or obesity (OR: 2.89; 95% CI: 1.78, 4.69) before pregnancy and with GWG above the IoM recommendations. Similar to our results, tendencies of higher risks also were found for underweight, overweight, and obese women with GWG below or above the IoM recommendations.

Wojcicki (2) in her review showed that 10 of the 13 studies reviewed found an association between higher prepregnancy BMI and risks of inability to sustain breastfeeding. Again, only a few of these studies were able to model interactions between prepregnancy BMI and GWG on the ability to sustain breastfeeding, although independent effects of GWG in relation to the IoM recommendations on breastfeeding duration have been shown (15, 16, 30). Li et al. (15) in their evaluation of low-income US women (see above) did not find any significant interaction between maternal prepregnancy BMI and GWG on breastfeeding maintenance. This may reflect the smaller sample size for these analyses (n = 13,234) as well as the short duration of breastfeeding (6 wk). Similarly, Hilson et al. (16) in their evaluation of 2783 American women who initiated breastfeeding found no significant interactions between prepregnancy BMI and GWG on duration of exclusive or any breastfeeding, also likely because of the small sample size. Furthermore, Baker et al. (31) evaluated associations between prepregnancy BMI, GWG, and breastfeeding among 37,459 women giving birth between 1999 and 2002 within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Here, GWG was not expressed in relation to the IoM recommendations but as <8, 8–15.9, and ≥16 kg. The authors did not find any significant interaction between maternal prepregnancy BMI and GWG in their effects on the ability to sustain full or any breastfeeding. This may reflect that GWG was modeled as 3 absolute weight categories. It may be that GWG is relevant only when expressed in relation to prepregnancy BMI, as is the case when the IoM recommendations are used as the basis for the categorization. Finally, Bartok et al. (3) recently evaluated the combined effects of prepregnancy BMI and GWG on ability to sustain breastfeeding among 718 American mothers randomly assigned to receiving standard medical care after delivery or a single home nurse visit. Here, overweight and obese women with GWG above recommendations breastfed for a shorter duration than did women with a normal BMI and GWG according to recommendations. In addition, obese women with GWG above recommendations had a shorter breastfeeding duration than did normal-weight women with GWG above recommendations. However, in this small study, these associations all disappeared in multivariate models controlling for known confounders.

Few previous studies have been able to evaluate the effects of maternal medical conditions and obesity on ability to breastfeed. An American national cohort study by Kitsantas and Pawloski (32) found that maternal prepregnant overweight or obesity only constituted a risk factor for unsuccessful initiation of breastfeeding if the mother also had a medical condition or labor/delivery complications. Women with medical conditions or labor/delivery complications also were at higher risk of inability to sustain breastfeeding. Our findings that women with more positive health conditions were at higher risk are difficult to interpret and may be chance findings. They could also indicate the complex relations between maternal nutrition and health and breastfeeding ability.

In conclusion, our results show that maternal prepregnant overweight or obesity are important risk factors for inability to initiate or sustain breastfeeding; the risks increase with degree of obesity. In addition, maternal prepregnant underweight is a risk factor. In addition, experiencing GWG above or below recommendations further adds to the risk. These findings are important in the public health efforts to ensure women and their offspring optimal long-term health.

Acknowledgments

AW, ALB, MH, HMM, and LL conceived the study; AW, ALB, MB, and MH analyzed the data; and AW performed the statistical analysis, wrote the draft of the manuscript, and had primary responsibility for final content. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically reviewed, read, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: GWG, gestational weight gain; IoM, Institute of Medicine; MBRN, Medical Birth Registry of Norway; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study; NOK, Norwegian crowns.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2003;916. [PubMed]

- 2.Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:341–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartok CJ, Schaefer EW, Beiler JS, Paul IM. Role of body mass index and gestational weight gain in breastfeeding outcomes. Breastfeed Med 2012;7:448–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandhagen M, Lissner L, Brantsaeter AL, Meltzer HM, Häggkvist AP, Haugen M, Winkvist A. Breastfeeding in relation to weight retention up to 36 months post partum in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study—modification by socioeconomic status? Public Health Nutr 2013;6:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Natland ST, Nilsen TIL, Midthjell K, Frost Andersen L, Forsmo S. Lactation and cardiovascular risk factors in the mothers in a population-based study: the HUNT-study. Int Breastfeed J 2012;7:8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Natland Fagerhaug T, Forsmo S, Wenberg Jacobsen G, Midthjell K, Frost Andersen L, Nilsen TIL. A prospective population-based cohort study of lactation and cardiovascular disease mortality: the HUNT-study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1070–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor JS, Kacmar JE, Nothnagle M, Lawrence RA. A systematic review of the literature associating breastfeeding with type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr 2005;24:320–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund-Blix NA, Stene LC, Rasmussen T, Torjesen PA, Andersen LF, Rønningen KS. Infant feeding in relation to islet autoimmunity and type I diabetes in genetically susceptible children: the MIDIA study. Diabetes Care 2015;38:257–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Harder T, Bergmann R, Kallischnigg G, Plagemann A. Duration of breastfeeding and risk of overweight: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Davey Smith G, Cook DG. Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: a quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics 2005;115:1367–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunsberger M; IDEFICS Consortium. Early feeding practices and family structure: associations with overweight in children. Proc Nutr Soc 2014;73:132–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amir LH, Donath S. A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2007;7:9–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thulier D, Mercer J. Variables associated with breastfeeding duration. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2009;38:259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, editors; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed]

- 15.Li R, Jewell S, Grummer-Strawn L. Maternal obesity and breast-feeding practices. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:931–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilson JA, Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is associated with earlier termination of breast-feeding among white women. J Nutr 2006;136:140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K, Nystad W, Skjaerven R, Stoltenberg C. Cohort profile: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:1146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, Skjaerven R, Melve KK, Schreuder P, Alsaker ER, Haug RK, Daltveit AK, Magnus P. Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irgens LM. The Medical Birth Registry of Norway: epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:435–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.fhi.no/morogbarn [Internet]. MoBa website [cited 2014 Dec 3]. Available from: www.fhi.no/morogbarn.

- 21.World Health Organization. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Report of an expert consultation. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2001.

- 22.World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Part 1. Definitions [cited 2012 Jun 8]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596664_eng.pdf.

- 23.Häggkvist AP, Brantsaeter AL, Grjibovski AM, Helsing E, Meltzer HM, Haugen M. Prevalence of breast-feeding in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study and health service-related correlates of cessation of full breast-feeding. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:2076–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000;894:i–xii, 1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomsen LCV, Klungsoyr K, Roten LT, Tappert C, Araya E, Baerheim G, Tollaksen K, Fenstad MH, Macsali F, Austgulen R, et al. Validity of the diagnosis of pre-eclampsia in the Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:943–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker JL, Gamborg M, Heitmann BL, Lissner L, Sorensen TIA, Rasmussen KM. Breastfeeding reduces postpartum weight retention. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:1543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy People 2020. Objectives for the nation. 2014 [cited 2014 May 19]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/policy/hp2010.htm.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding report card 2013, United States: outcome indicators. 2013 [cited 2014 May 19]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm.

- 29.Kristiansen AL, Lande B, Øverby NC, Andersen LF. Factors associated with exclusive breast-feeding and breast-feeding in Norway. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:2087–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manios Y, Grammatikaki E, Kondaki K, Ioannu E, Anastasiadou A, Birbilis M. The effect of maternal obesity on initiation and duration of breastfeeding in Greece: the GENESIS study. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker JL, Michaelsen KF, Sörensen TIA, Rasmussen KM. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with early termination of full and any breastfeeding in Danish women. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:404–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitsantas P, Pawloski LR. Maternal obesity, health status during pregnancy, and breastfeeding initiation and duration. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;23:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]