Abstract

Objective

Even though childhood fever is mostly self-limiting, children with fever constitute a considerable workload in primary care. Little is known about the number of contacts and management during general practitioners’ (GPs) out-of-hours care. We investigated all fever related telephone contacts, consultations, antibiotic prescriptions and paediatric referrals of children during GP out-of-hours care within 1 year.

Design

Observational cohort study.

Setting and patients

We performed an observational cohort study at a large Dutch GP out-of-hours service. Children (<12 years) whose parents contacted the GP out-of-hours service for a fever related illness in 2012 were included.

Main outcome measures

Number of contacts and consultations, antibiotic prescription rates and paediatric referral rates.

Results

We observed an average of 14.6 fever related contacts for children per day at GP out-of-hours services, with peaks during winter months. Of 17 170 contacts in 2012, 5343 (31.1%) were fever related and 70.0% resulted in a GP consultation. One in four consultations resulted in an antibiotic prescription. Prescriptions increased by age and referrals to secondary care decreased by age (p<0.001). The majority of parents (89.5%) contacted the out-of-hours service only once during a fever episode (89.5%) and 7.6% of children were referred to secondary care.

Conclusions

This study shows that childhood fever does account for a large workload at GP out-of-hours services. One in three contacts is fever related and 70% of those febrile children are called in to be assessed by a GP. One in four consultations for childhood fever results in antibiotic prescribing and most consultations are managed in primary care without referral.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to provide an insight into the workload of childhood fever at one of the largest general practitioner (GP) out-of-hours centres in the Netherlands during a full year.

Data from these children were routinely collected during normal GP out-of-hours care; therefore, GPs and triage nurses could not adapt their behaviour to desirable outcomes.

Since this is a study based on actual medical records, we are dependent on the individual GP’s quality of keeping such medical records.

Introduction

Fever in children is a common reason for parents to consult primary care in general and general practice (GP) out-of-hours services in particular.1 2 Even though childhood fever is mostly self-limiting and usually does not require treatment, it constitutes a considerable workload, especially in primary care.3 A European study showed that a quarter of the out-of-hours consultations are for children under the age of 12 years. Of these consultations, infections and fever are the most common reasons for encounter.2

In the Netherlands, GP out-of-hours care is organised in large-scale GP cooperatives.4 After working hours, parents of a febrile child are referred to these GP cooperatives when they contact their GP. Telephonic contacts are then handled by trained triage nurses who work according to the Dutch Triage System.5 6 Parents can either receive advice from the nurse or are offered a consultation with one of the GPs on call.

Though there have been some studies investigating antibiotic prescription rates during GP out-of-hours, at present it is largely unknown how great the exact workload of childhood fever during GP out-of-hours care is and which management strategies (telephone advice, medication prescription, referral to a paediatrician) are being executed by GPs and triage nurses on call. In other words, we know something about antibiotic prescriptions and the proportion of fever related consultation rates, but an overall overview of what happens with febrile children who visit a GP out-of-hours cooperative is lacking. In order to develop interventions to increase parental self-management strategies, to reduce medicalisation of mostly self-limiting common infections and thereby reduce pressure on the workload in general practice, it is important to know how childhood fever contacts are managed during out-of-hours care.

This study assesses the number of childhood fever related contacts, the number of contacts leading to a consultation, resulting antibiotic prescriptions, paediatric referrals and reconsultations for children under the age of 12 during out-of-hours care in the Netherlands.

Methods

Design and setting

GP out-of-hours services in the Netherlands are organised in large-scale cooperatives. There are 120–130 GP out-of-hours services in the Netherlands, varying from 50 to 200 GPs.7 These cooperatives cover primary care by rotating shifts of GPs during evenings, nights and weekends. For this observational study, we used the medical record database of the Nightcare GP cooperative out-of-hours service in Heerlen (the Netherlands).The Nightcare GP out-of-hours service is located in a multiethnic, moderate to low socioeconomic area; it consists of 132 GPs providing care to approximately 270 000 inhabitants living in this South-Eastern district.8 As such, it is one of the larger out-of-hours services in the Netherlands.

Data collection and variables

GPs and triage nurses at the out-of-hours service are obliged to digitally enter all information. The registered patient data consist of information from telephone triage, given advice, consultation report, (working) diagnosis, International Classification for Primary Care (ICPC) code,9 treatment and prescribed medication. Children were defined as having fever, and thus eligible for inclusion, if they met one of the following criteria: fever reported by parents at the initial telephone contact, either mentioned or measured; fever mentioned during the consultation or febrile convulsion.

First, we retrieved the anonymised medical records of all children <12 years whose parents contacted the GP out-of-hours service between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2012. All contacts, including reconsultations of a child during the same episode of illness, were selected. A contact (telephonic advice or consultation) occurring within the same fever episode, within 7 days after the initial contact, was considered a reconsultation. To select all children with fever, different procedures were executed. First, we sorted selected contacts by ICPC code and selected children with fever related ICPC codes.9 Contacts where the triage nurse selected fever as a key symptom were also selected. After this, we manually searched through the remaining contacts on the synonyms fever and temperature to ensure no contacts were missing. We distinguished a temperature of <38°C (no fever), ≥38°C (fever) and unknown temperature.

When contacting the out-of-hours service, parents could be offered telephonic advice by a triage nurse or a consultation (face-to-face contact with the GP at the out-of-hours service). For those children receiving a consultation, we classified management into three groups: no medication prescription; prescription for medication; referral to secondary care. Prescribed medication was divided in the following groups: antibiotics, over-the-counter (OTC) medication or other medication.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS V.19.0. Analysis was based on frequencies and descriptive statistics and χ2 tests were performed to identify independent associations for antibiotic prescriptions (yes/no) and referral to secondary care (yes/no) as independent outcomes. We also analysed the number of contacts per month to examine seasonal influence.

Results

Population characteristics

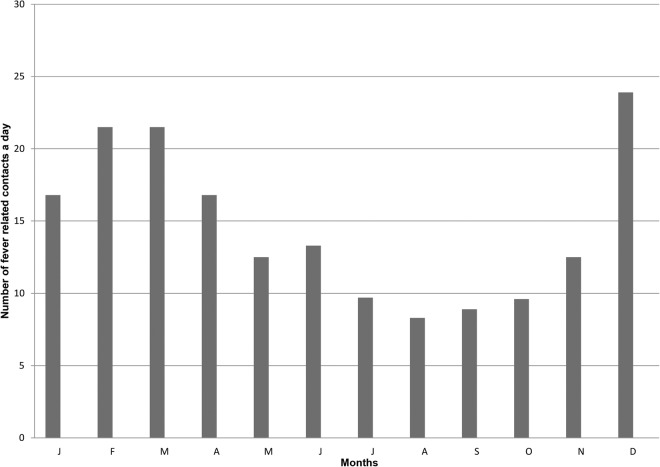

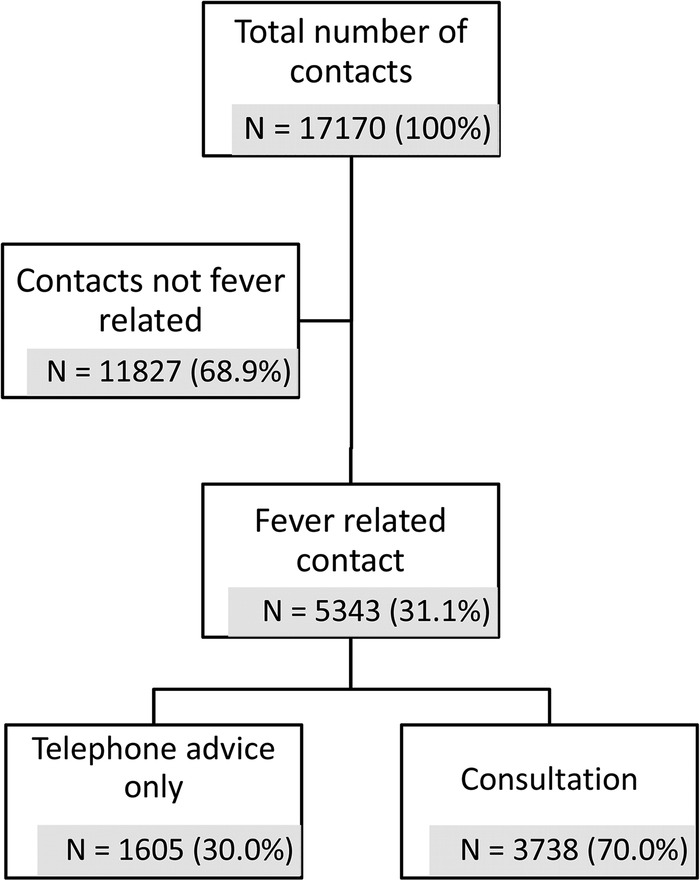

In 2012, there were 78 514 contacts and 39 519 consultations in total for all age categories at the out-of-hours centre. Of these contacts, 17 170 were for children <12 years, of which 5343 (31.1%) were fever related (figure 1). Mean age was 2.8 years (SD±2.5 years). Gender and age distribution are presented in table 1. Most fever related contacts were for children aged 1–5 years (table 2). In 2012, there were on average 14.6 fever related contacts for children per day, with peaks in workload during the months of December to April (figure 2). Seventy per cent of all fever related contacts resulted in a GP consultation (figure 1). The most frequently used ICPC codes were A99.00 (general disease not specified; 74.3%), A03.00 (fever; 4.1%), H71.00 (acute otitis media; 4.2%) and R74.00 (upper respiratory infection acute; 4.8%).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of all children <12 years contacting the general practitioner out-of-hours service.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (n=5343)

| Characteristics | Number of contacts (%) |

|---|---|

| Male sex | 2830 (53) |

| Age distribution | |

| <1 month | 13 (0.2) |

| 1 month to <3 months | 207 (3.9) |

| 3 months to <6 months | 310 (5.8) |

| 6 months to <12 months | 902 (16.9) |

| 1 year to <5 years | 2943 (55.1) |

| 5 years to <12 years | 968 (18.1) |

Table 2.

Fever related contacts: distribution of phone advice and consultation by age

| <1 month n=13 |

1 to <3 months n=207 |

3 to <6 months n=310 | 6 to <12 months n=902 | 1 to <5 years n=2943 | 5 to <12 years n=968 | Total n=5343 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phone advice N (%) | 1 (7.7) | 83 (40.1) | 88 (28.4) | 306 (33.9) | 860 (29.2) | 267 (27.6) | 1605 (30.0) |

| Consultation N (%) | 12 (92.3) | 124 (59.9) | 222 (71.6) | 596 (66.1) | 2083 (70.8) | 701 (72.4) | 3738 (70.0) |

Figure 2.

Daily distribution per month of contacts of febrile children <12 years in 2012.

Management

GPs prescribed medication in 40.6% of consultations. One in four consultations for childhood fever resulted in an antibiotic prescription (table 3). Antibiotic prescription increased significantly with age (table 4, p<0.001). Of all fever related contacts, 283 (7.6%) children were referred to secondary care. The number of referrals to secondary care decreased with increasing age, from 66.7% for children younger than 1 month to 6.0% for children in the age category of 5–12 years (table 4, p<0.001). We found no relationship between gender and prescription or referral rates.

Table 3.

Management of fever related consultations for children <12 years

| Consultation | N=3738* (%) |

|---|---|

| No prescription | 1939 (51.9) |

| Prescription† | 1516 (40.6) |

| Antibiotics | 936 (25.0) |

| OTC | 302 (8.1) |

| Other medication | 278 (7.4) |

| Referral to secondary care | 283 (7.6) |

*Owing to rounding of percentages, the columns do not add up to 100%.

†Excluding advice only on OTC medication.

OTC, over-the-counter.

Table 4.

Antibiotic prescriptions and secondary care referrals during consultations, by age group

| Age category | Number of GP consultations | Number of antibiotic prescriptions (%) | Number of secondary care referrals n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <1 month | 12 | 0 (0) | 8 (66.7) |

| 1 to <3 months | 124 | 0 (0) | 27 (21.8) |

| 3 to <6 months | 222 | 30 (13.5) | 34 (15.3) |

| 6 to <12 months | 596 | 114 (19.1) | 40 (6.7) |

| 1 to <5 years | 2083 | 573 (27.5) | 132 (6.3) |

| 5 to <12 years | 701 | 219 (31.2) | 42 (6.0) |

GP, general practitioner.

Temperature and reconsultations

GPs failed to report a temperature in one-third of the consultations. There were 3793 individual children accounting for 5343 fever related contacts. This results in an average of 1.3 (SD±0.6) contacts per child for parents who contacted the out-of-hours service that year. In total 89.5% of the parents contacted the out-of-hours service only once during a fever episode. For the remaining contacts, the number of reconsultations for one illness episode ranged from 2 to 4 times.

Discussion

Main findings

This study shows that 31% of the total 17 170 contacts for children under the age of 12 years at GP out-of-hours care are fever related. Most contacts were for children in the age category 1–5 years, and of all fever related contacts 70% resulted in a GP consultation. During one in four consultations, antibiotics were prescribed and more than 92% of childhood fever consultations were managed by GPs without referral to secondary care. Most parents (89.5%) contacted the out-of-hours service only once during a fever episode.

Comparison with existing literature

When examining consultation rates across different age categories, there are several interesting aspects to consider. In agreement with the advice of the Dutch College of General Practitioners to see children <1 month with a fever as soon as possible, the consultation rate was higher for these children (92.3%).10 The small number of children under the age of 1 month (n=13) could be explained by the intensive care provided directly after birth by the maternity care centres and the well-baby centres, making parents seek other medical help less often. Surprisingly, consultation rates for children aged between 1 and 3 months were below the average with 59.9%, even though the advice for this age is to see them within 1 day.10 The difference in consultation rates for this age category could be explained by the fact that in The Netherlands children receive their first vaccination within 6–9 weeks after birth, and one of the most common side effects of this specific vaccination is fever. Triage nurses might give telephone advice more often instead of a consultation when fever is related to vaccination, in line with national recommendations. However, GPs and triage nurses should realise that if a fever is not vaccine related, children aged 1–3 months should be called in to be assessed by a GP during out-of-hours care. As expected in agreement with the guidelines and incidence rates of infections, the number of referrals to secondary care decreased with age.11

We also found that GPs failed to report a temperature in one-third of the consultations. This is in agreement with a previous study that showed that overall documentation of vital signs by GPs is relatively poor in children presenting with acute infections.12

The overall prescription rate during consultations was high (40.6%). Of the prescribed medications, 19.9% were OTC drugs. An explanation for prescribing OTC could be that GPs prescribed medication to give parents ‘something’ instead of leaving them empty-handed. Another explanation could be that by prescribing OTC, GPs and parents experience more certainty that the correct drug was prescribed. The prescription of OTC is an underestimation of the use of OTC after the consultation since advices by the GP to use OTC drugs are not included. Since the telephone contacts are handled by triage nurses, there were no telephonic prescriptions. This is different from other countries where (topical) antibiotics are even prescribed by telephone.13

The antibiotic prescription rate of 25% in this study was somewhat lower than previously described 36.3%14 and 36.515 in other Dutch studies. A possible explanation for the difference between our study and the two previous Dutch studies could be that we used different inclusion criteria leading to a different illness severity and other prescription behaviour. Both our study and these previous studies describe an increase of antibiotic prescription by age, which is in agreement with a Norwegian study among children with respiratory tract infections during daytime GP care.16 However, another study among children during regular daytime care showed the contrary.17 One explanation for this difference could be that older children who are assessed during GP out-of-hours care are potentially more severely ill than those children who are assessed during regular daytime GP care. Moreover, parents of young children might be worried sooner, resulting in increased and more frequent out-of-hours attendance, with a larger proportion of younger children having self-limiting infections not requiring treatment. This was also found in a study examining which urgent care services parents of febrile children use.18 However, there are no studies comparing illness severity of febrile children consulting during daytime and out-of-hours care, meaning these are only hypotheses. Moreover, these studies had different inclusion criteria also explaining potential differences.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to provide an insight into the workload of childhood fever at a GP out-of-hours centre during a full year. The most important strengths of this study were the number of participants and the fact that the data of these children were routinely collected during normal GP out-of-hours care. GPs and triage nurses did not know we were studying their management and could therefore not adapt their behaviour to desirable outcomes.

The aim of the study was to obtain a more detailed insight into fever related contacts for children and the associated workload during GP out-of-hours care. For this reason, we chose a broad definition for fever related contacts, namely children who subjectively presented with fever during the initial telephone contact with the out-of-hours service. By selecting children who subjectively presented with fever, these results could be an overestimation of the number of children actually having fever. An important limitation of this study is the fact that because we used actual medical records, we are dependent on the individual GP’s quality of keeping such medical records, meaning these data are always dependent on the interpretation of the triage nurses and GPs and their completeness of filling in these records. An important observation that illustrates this is the fact that the most commonly used ICPC code by far was A99.00 (General disease not specified), which suggests that instead of using the ICPC code to specify a disease, it is probably considered as an obligation to fill in. As the data also showed, there is still a lot of room for improvement when it comes to systematically registering, for example, a vital sign as the temperature that was measured. We do not know to what extent this affected the validity of our results. Since registration is sometimes lacking, we cannot exclude the possibility that this is an under-registration and there are more fever related contacts than we were able to identify. However, we took several steps to enhance the completeness of the data and believe that these data are indispensable to obtain a pragmatic overview of the workload of childhood fever during GP out-of-hours care.

In this study, we only reported reconsultations at the out-of-hours service; data regarding recontacts during regular hours care are missing. This means that the number of reconsultations is most likely an underestimation of the real number of contacts for that common infection episode.

Although we only used data from one GP out-of-hours service, we think that our findings can be generalised to other out-of-hours services in the Netherlands, since all GP out-of-hours services in the Netherlands are organised in the same way and do work with the same Dutch guidelines and triage reporting system.6 In addition, the organisation of out-of-hours healthcare in Scandinavia, Australia and the UK is comparable, at least to a certain extent, making these results also relevant for other countries.4 However, it is important to realise that this was a single centre study and that results should be generalised only with great caution, especially considering the fact that the average education level in this region is lower than the national average.19

Practice implications

This study shows that childhood fever constitutes a considerable workload in GP out-of-hours services with many initial contacts leading to face-to-face consultations with a GP, and we additionally showed that antibiotic prescription rates are still high during out-of-hours care, leaving room for improvement for mostly self-limiting illnesses.

On the other hand, we acknowledge that although some contacts could potentially be prevented by increasing parental self-management strategies, some children definitely need to be assessed and a subgroup of children presenting to out-of-hours GP do need antibiotics to treat serious infections. Differentiating these cases from the large group with self-limiting symptoms can be challenging, especially in a setting where the GP typically does not know the child and its family.20 Since GPs did not report a temperature in 30% of the fever related consultations, it is important to draw attention to complete registration of vital characteristics such as temperature, as well as to facilitate the development of better predictors of serious infections in general practice.21 Future research should provide insights into the motivations and expectations of (frequent attending) parents when they contact the GP out-of-hours service, alongside the motivations of GPs to prescribe antibiotics to these patients, thereby providing leads for interventions aimed at reducing the number of consultations and antibiotic prescriptions, without increasing complications and while providing a proper safety netting for parents who typically seek reassurance.22 23 Previous studies have shown that an information exchange tool is effective in reducing the number of antibiotic prescriptions and intentions to reconsult in children with upper respiratory tract infections24 and that such a tool can provide a safety net advice for parents.25 We believe that this strategy could also be used in children presenting with a fever.

Conclusion

This study shows that the GP's perception of seeing many febrile children during out-of-hours care is true as childhood fever does actually account for a large workload at GP out-of-hours services. One in three contacts is fever related and 70% of those febrile children are called in to be assessed by a GP. One in four consultations for childhood fever results in antibiotic prescribing and most consultations are managed in primary care without referral. Future research should provide deeper insights into the motivations and expectations of parents and GPs who prescribe antibiotics to these patients, thereby providing leads for interventions aimed at reducing the number of consultations and antibiotic prescriptions for febrile children during out-of-hours care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The Nightcare GP out-of-hours service for providing the data that were used and Math Hundscheid for data support.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Eefje de Bont at @eefje_de_bont

Contributors: JWLC and EGPMdB conceived the idea for the study. JMML, NL, DASH and EGPMdB performed the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and findings and commented on the first draft and all further revisions. The corresponding author (EB) had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: Jochen Cals is supported by a Veni-grant (91614078) of the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Maastricht University Medical Centre (ref. number NL14-4-069).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hay AD, Heron J, Ness A. The prevalence of symptoms and consultations in pre-school children in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC): a prospective cohort study. Fam Pract 2005;22:367–74. 10.1093/fampra/cmi035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huibers LA, Moth G, Bondevik GT et al. . Diagnostic scope in out-of-hours primary care services in eight European countries: an observational study. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:30 10.1186/1471-2296-12-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitburn S, Costelloe C, Montgomery AA et al. . The frequency distribution of presenting symptoms in children aged six months to six years to primary care. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2011;12:123–34. 10.1017/S146342361000040X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huibers L, Giesen P, Wensing M et al. . Out-of-hours care in western countries: assessment of different organizational models. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:105 10.1186/1472-6963-9-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Ierland Y, van Veen M, Huibers L et al. . Validity of telephone and physical triage in emergency care: the Netherlands Triage System. Fam Pract 2011;28:334–41. 10.1093/fampra/cmq097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stichting Nederlandse Triage Standaard. Nederlandse Triage Standaard [Netherlands Triage System]. www.hetnts.nl (accessed 1 Oct 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giesen P, Smits M, Huibers L et al. . Quality of after-hours primary care: as narrative review of the Dutch solution. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:108–13. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huisartsen Oostelijk Zuid-Limburg. Organisatie. Secondary Organisatie, 2013. http://www.huisartsen-ozl.nl/ (accessed 1 Jun 2014).

- 9.World Organization of National Colleges Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners. ICPC: international classification of primary care. Oxford England, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oteman N, Berger MY, Boomsma LJ et al. . Summary of the practice guideline ‘Children with fever’ (Second Revision) from the Dutch College of General Practitioners. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2008;152:2781–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van den Bruel A, Bartholomeeusen S, Aertgeerts B et al. . Serious infections in children: an incidence study in family practice. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:23 10.1186/1471-2296-7-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blacklock C, Haj-Hassan TA, Thompson MJ. When and how do GPs record vital signs in children with acute infections? A cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e679–86. 10.3399/bjgp12X656810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huibers L, Moth G, Christensen MB et al. . Antibiotic prescribing patterns in out-of-hours primary care: a population-based descriptive study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2014;32:200–7. 10.3109/02813432.2014.972067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elshout G, Kool M, Van der Wouden JC et al. . Antibiotic prescription in febrile children: a cohort study during out-of-hours primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:810–18. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.06.110310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elshout G, van Ierland Y, Bohnen AM et al. . Alarm signs and antibiotic prescription in febrile children in primary care: an observational cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e437–44. 10.3399/bjgp13X669158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fossum GH, Lindbaek M, Gjelstad S et al. . Are children carrying the burden of broad-spectrum antibiotics in general practice? Prescription pattern for paediatric outpatients with respiratory tract infections in Norway. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002285 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Bont EG, van Loo IH, Dukers-Muijrers NH et al. . Oral and topical antibiotic prescriptions for children in general practice. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:228–31. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maguire S, Ranmal R, Komulainen S et al. . Which urgent care services do febrile children use and why? Arch Dis Child 2011;96:810–16. 10.1136/adc.2010.210096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Central Bureau of Statistics. Hoogopgeleiden, 2014. http://www.compendiumvoordeleefomgeving.nl/indicatoren/nl2100-Opleidingsniveau-bevolking.html?i=15-12 (accessed 1 Dec 2014).

- 20.Buntinx F, Mant D, Van den Bruel A et al. . Dealing with low-incidence serious diseases in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:43–6. 10.3399/bjgp11X548974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nijman RG, Zwinkels RL, van Veen M et al. . Can urgency classification of the Manchester triage system predict serious bacterial infections in febrile children? Arch Dis Child 2011;96:715–22. 10.1136/adc.2010.207845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Bont EG, Francis NA, Dinant GJ et al. . Parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice in childhood fever: an internet-based survey. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e10–16. 10.3399/bjgp14X676401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones CH, Neill S, Lakhanpaul M et al. . Information needs of parents for acute childhood illness: determining ‘what, how, where and when’ of safety netting using a qualitative exploration with parents and clinicians. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003874 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis N, Butler C, Hood K et al. . Effect of using an interactive booklet about childhood respiratory tract infections in primary care consultations on reconsulting and antibiotic prescribing: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;339:b2885 10.1136/bmj.b2885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francis NA, Phillips R, Wood F et al. . Parents’ and clinicians’ views of an interactive booklet about respiratory tract infections in children: a qualitative process evaluation of the EQUIP randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:182 10.1186/1471-2296-14-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]