Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of high-intensity statin therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Design

A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing high-intensity statin therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg or rosuvastatin 20/40 mg) with moderate/mild statin treatment or placebo were derived from the databases (PubMed, Embase, Ovid, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, and ISI Web of Knowledge).

Outcome measure

Primary end points: clinical events (all-cause mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction and heart failure); secondary end points: serum lipid, renal function changes and adverse events.

Results

A total of six RCTs with 10 993 adult patients with CKD were included. A significant decrease in stroke was observed in the high-intensity statin therapy group (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.85). However, the roles of high-intensity statin in decreasing all-cause mortality (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.09), myocardial infarction (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.18) and heart failure (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.13) remain unclear with low evidence. High-intensity statin also had obvious effects on lowering the LDL-C level but no clear effects on renal protection. Although pooled results showed no significant difference between the intervention and control groups in adverse event occurrences, it was still insufficient to put off the doubts that high-intensity statin might increase adverse events because of limited data sources and low quality evidences.

Conclusions

High-intensity statin therapy could effectively reduce the risk of stroke in patients with CKD. However, its effects on all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, heart failure and renal protection remain unclear. Moreover, it is hard to draw conclusions on the safety assessment of intensive statin treatment in this particular population. More studies are needed to credibly evaluate the effects of high-intensity statin therapy in patients with CKD.

Keywords: High-intensity statin therapy, Chronic kidney disease, Cardiovascular events, Meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of high-intensity statin therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

High-intensity statin therapy was found to have superior effects on decreasing the incidence of stroke in patients with CKD.

Lack of high-quality primary studies and most trials included are post hoc studies.

There are only six trials included in our meta-analysis, and the small sample size and few reported end points may have an influence on the power of this study.

Since most of the patients enrolled in this analysis had moderate CKD, the available evidences are not suitable for patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (GFR categories G1–G2), end-stage renal disease and haemodialysis.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is acknowledged as a cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk equivalent. The incidence of CVD was much higher in patients with CKD than in general population,1–3 and CVD has already become the leading cause of death in patients with CVD. As we all known, dyslipidemia caused by renal dysfunction is the most common complication in patients with CKD, and it will in turn contribute to further progression of renal damage and deterioration of renal function, which are mainly characterised with a continuously decreasing estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).4 It has been proved that a decreasing eGFR is associated with CVD independently of other risk factors.5 Therefore, the initiation of lipid regulation therapy in patients with CKD as early as possible is quite important and well accepted.

Statin (inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase), which is considered to be the best remedy for lipid regulation, has gained extensive acceptance as a principal therapy for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events and death both in confirmed patients with CVD and high-risk individuals.6–8 Its excellent cardiovascular protection in these populations does not rely only on lipid regulation effect, but also on its pleiotropic effects including anti-inflammation and stabilising plaque. Also, there is a linear relationship between statin's cardiovascular protection effect and the intensity of statin therapy. A meta-analysis of 40 000 patients has found that high-intensity statin therapy has greater efficacy in reducing the risk of non-fatal events and mortality when compared with a moderate dose.9 Whether high-intensity statin therapy can be effectively and safely used in patients with CKD is still unclear and this question has caused lots of attention from clinical workers worldwide.

Several recent meta-analyses have investigated the effect of statins in patients with CKD and demonstrated that statin therapy could decrease mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with CKD, but not those treated with haemodialysis.10–15 However, all of these studies have not evaluated the effect of high-intensity statin therapy on clinical outcomes in patients with CKD. Furthermore, although the 2013 KDIGO (the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) clinical practice guideline has recommended initiation of statin treatment in patients with CKD, it does not give out details about statin doses.16 Whether high-intensity statin benefit more in this particular population remains unclear. Moreover, the increased risks of harm and complication of clinical practice with intensification warrant additional focus. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of high-intensity statin therapy versus moderate/mild-intensity statin or placebo in patients with CKD.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Prospective randomised controlled trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of high-intensity statin therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg or rosuvastatin 20/40 mg) in patients with CKD were included. The CKD was defined according to the KDIGO clinical practice guideline (available at http://www.kdigo.org). The outcome measurements contained primary end points (all-cause mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction and heart failure) and secondary end points (serum lipid change, renal function and adverse events). We excluded studies with a follow-up of less than 8 weeks because such studies would not permit the detection of the related mortality or cardiovascular outcomes, and the steady change of renal function and incidence of adverse events could not be effectively recorded with such a short follow-up duration. We also excluded studies that included patients younger than 18 years of age and studies with no access to full text for quality assessment and data extraction.

Search strategy and study selection

We searched the databases (PubMed, Embase, Ovid, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, and ISI Web of Knowledge) for studies published on 18 February 2015, using the following search items: randomized controlled trial, controlled clinical trial, randomly, prospective, high-intensity, high-dose, high-strength, intensive, statin, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, lovastatin, mevastatin, fluvastatin, cerivastatin, aggressive lipid lowering, chronic kidney disease, chronic renal disease, chronic renal insufficiency, chronic renal failure. This search was supplemented with citation tracking of the reference lists including articles and relevant review articles. Two investigators reviewed all the databases searched and retrieved the literature which met our eligibility criteria by title and abstract, and then the full texts independently. Disagreements were solved by discussion or by searching for opinions from a third party.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The same two investigators reviewed the full texts of eligible studies independently and collected data for study and patient characteristics, interventions and items for bias risk assessing. We extracted data on the following outcomes: all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, the change of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and renal function, and adverse events. The extraction results of the two reviewers were compared. Disagreements were solved through discussion, and a third reviewer was involved to achieve a consensus when necessary. The bias of the included study was assessed by Cochrane Collaboration’s tool17 and evidence classification was performed by software GRADEprofiler according to the grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) criteria.

Data synthesis and analysis

The meta-analysis was performed by software RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration) and the statistics were calculated by the Mantel-Haenszel statistical method. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated relative risk (RR) and corresponding 95% CI. For continuous variables (change from baseline to follow-up), we used weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% CI to express the outcomes. Statistic heterogeneity was measured using the χ2 (Cochran Q) statistic and I2 test. Heterogeneity was not considered as significant when I2<50%. Pooled analyses were conducted within fixed effect models, whereas random effect models were applied in conditions of significant heterogeneity among included studies. Results should be only descriptive if data cannot be combined. For all clinical outcomes, an intention-to-treat analysis was utilised. The study was performed in compliance with the quality of reporting for meta-analyses (PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement).18

Results

Eligible studies

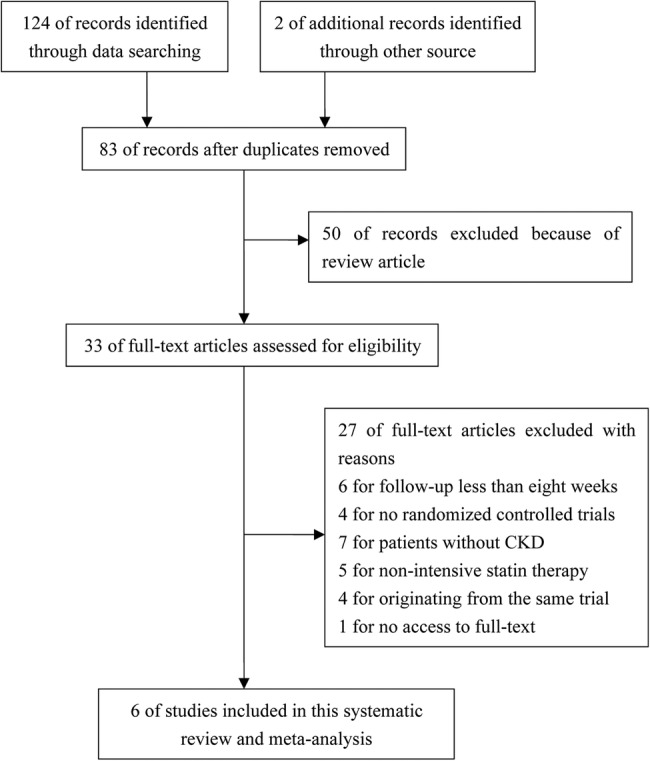

The derivation of the included studies and the process were described in figure 1. Of 126 potentially relevant trials identified and screened, 33 were retrieved for a full critical appraisal. Six trials18–23 were included in the review at last, enrolling 10 993 patients with CKD, with 5537 patients randomised to the high-intensity statin arm and 5456 patients randomised to the control arm. The mean follow-up time ranged from 1.9 to 5 years. The baseline characteristics of the included trials were listed in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the process of selecting the eligible studies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of trials included in this systematic review and meta-analysis

| Study/ref | Year | Intensive statin therapy group/control group |

Diagnosis of CKD | Follow-up time Mean, years |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| interventions | n | Age Mean, years |

Male % | Mean LDL-C mg/dL |

Mean eGFR ml/min/1.73 m2 |

||||

| TNT19 | 2008 | Atorvastatin 80 mg/day vs 10 mg/day | 1602/1505 | 65.5/65.6 | 69.3/65.9 | 96.3/96.5 | 53.0/52.8 | eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 5.0 |

| ALLIANCE20 | 2009 | An LDL-C goal of <80 mg/dL or maximum dose of 80 mg/d vs usual care* | 286/293 | 65.6/64.8 | 75.9/77.8 | 148.2/146.0 | 51.3/51.1 | eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 4.5 |

| IDEAL21 | 2010 | Atorvastatin 80 mg/day vs simvastatin 20 or 40 mg/day | 1162/1159 | 67.0† | NA | 123.6† | 52.3/52.0 | eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 4.8 |

| JUPITER22 | 2010 | Rosuvastatin 20 mg/day vs placebo | 1638/1629 | 70‡ | 34.8§ | 109‡ | 56‡ | eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1.9 |

| PANDA23 | 2010 | Atorvastatin 80 mg/day vs 10 mg/day | 60/59 | 63.3/64.5 | 85/81 | 119.8/116 | 72/61 | Microalbuminuria or proteinuria | 2.1 |

| SPARCL24 | 2014 | Atorvastatin 80 mg/day vs placebo | 789/811 | 68.1/67.9 | 43.3/40.8 | 134.4/134.3 | 51.9/52.6 | eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 5.0 |

*Usual care as deemed appropriate by patients’ regular physicians.

†Mean for two group.

‡Median for two group.

§Percentage for two group.

ALLIANCE, Aggressive Lipid-Lowering Initiation Abates New Cardiac Events Study; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IDEAL, In Incremental Decrease in Endpoints Through Aggressive Lipid-lowering; JUPITER, Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention-an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NA, not available; PANDA, Protection Against Nephropathy in Diabetes with Atorvastatin; SPARCL, the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels; TNT, Treating to New Targets Study.

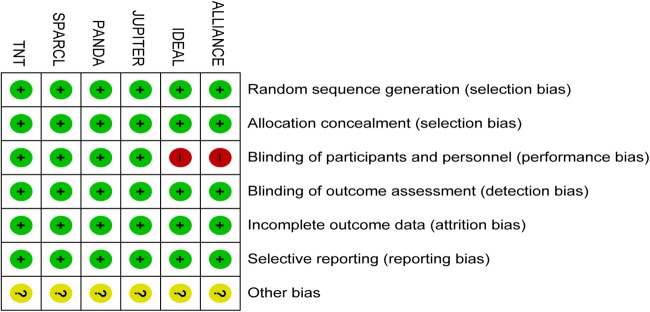

Among the six included trials, five used atorvastatin 80 mg as the high-intensity statin intervention and the remaining one used rosuvastatin 20 mg. The comparator treatments were moderate/mild-intensity statin therapy (including simvastatin 20–40 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg) and placebo. The patients with CKD in five of the included trials evidently suffered from clinical CVD (TNT,19 IDEAL,21 ALLIANCE,20 SPARCL24) and type 2 diabetes (PANDA23). Except for the patients from the PANDA trial who were diagnosed with CKD due to microalbuminuria and proteinuria, all the other participants were diagnosed with CKD because the level of eGFR was less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Furthermore, most of the enrolled patients had moderate CKD (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2), and very few had severe CKD (eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2). All trials had explicitly described the random sequence generation and allocation. Two trials were open-labelled but with blind outcome assessment and neither trial presented attrition and reporting bias. All studies appeared to undertake an intention-to-treat analysis according to initial random allocation. The judgements about the risk of bias of each trial are presented in figure 2. The evidence classification results were demonstrated in table 2.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review author judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. Green means low risk, red means high risk, yellow means unclear risk.

Table 2.

Summary of GRACE evidence profile

| Quality assessment |

Patients (n) |

Effect |

Quality | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Intensive statin therapy | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | |

| All-cause mortality | |||||||||||

| 5 | RCT | No serious | Serious* | No serious | Serious† | Undetected | 346/4748 (7.3%) |

384/4645 (8.3%) |

RR 0.85 (0.67 to 1.09) | 12 fewer per 1000 (from 27 fewer to 7 more) | ⊕⊕OO LOW |

| Stoke | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCT | No serious | No serious | No serious | No serious | Undetected | 144/4688 (3.1%) |

203/4586 (4.4%) |

RR 0.69 (0.56 to 0.85) | 14 fewer per 1000 (from 7 fewer to 19 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | No serious | Serious* | No serious | Serious† | Undetected | 118/3086 (3.8%) |

141/3081 (4.6%) |

RR 0.69 (0.4 to 1.18) | 14 fewer per 1000 (from 27 fewer to 8 more) | ⊕⊕OO LOW |

| Heart failure | |||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | No serious | Serious* | No serious | Serious† | Undetected | 111/3050 (3.6%) |

151/2957 (5.1%) |

RR 0.73 (0.48 to 1.13) | 14 fewer per 1000 (from 7 fewer to 19 fewer) | ⊕⊕OO LOW |

| Change of eGFR | |||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | No serious | No serious | No serious | No serious | Undetected | 2237 | 2263 | MD 1.09 higher (0.35 to 1.82 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

|

| Any serious adverse event | |||||||||||

| 2 | RCT | No serious | No serious | No serious | No serious | Undetected | 328/1698 (19.3%) | 336/1688 (19.9%) | RR 0.97 (0.85 to 1.11) | 6 fewer per 1000 (from 30 fewer to 22 more) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Persistent elevation of AST/ALT | |||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | No serious | Very serious‡ | No serious | Very serious§ | Undetected | 43/4209 (1.1%) | 6/3945 (0.15%) | RR 5.59 (0.40 to 77.37) | 9 more per 1000 (from 3 more to 24 more) | ⊕OOO VERY LOW |

| Myopathy | |||||||||||

| 2 | RCT | No serious | No serious | No serious | Serious† | Undetected | 3/2472 (0.1%) | 7/2440 (0.3%) | RR 0.42 (0.11 to 1.64 | 2 fewer per 1000 (from 3 fewer to 2 more) | ⊕⊕⊕O MODERATE |

| Rhabdomyolysis | |||||||||||

| 2 | RCT | No serious | Serious* | No serious | serious† | Undetected | 1/2427 | 2/2440 (0.1%) | RR 0.67 (0.11 to 4.07) | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 1 fewer to 3 more) | ⊕⊕OO LOW |

*Tests for heterogeneity, I2>50%.

†95%CI is wide.

‡I2>80%.

§95%CI is very wide.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RR, relative risk.

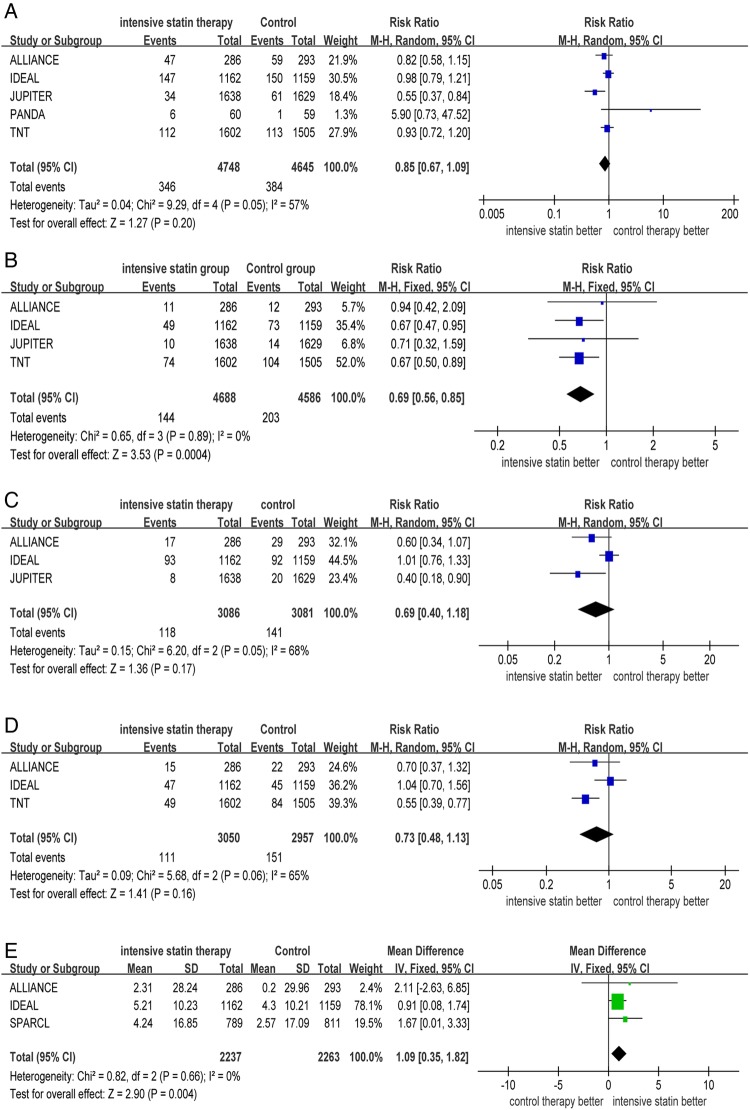

All-cause mortality

Data on all-cause mortality were available in 9393 patients from five studies. As shown in figure 3A, a total of 730 patients died during the follow-up period. Pooled analysis showed that there was a point estimate consistent with reduced all-cause mortality but with a CI that marginally included no effect (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.09).

Figure 3.

Forest plots for efficacy evaluation of intensive statin therapy for patients with CKD: all-cause mortality (A), stroke (B), myocardial infarction (C), heart failure (D), change of eGFR (E). CI, confidence intervals; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; RR, relative risk.

Stroke

Information about 347 strokes was available among 9274 patients. Results showed that compared with the control group, the high-intensity statin group had a lower incidence of myocardial infarction with a significant difference (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.85) (figure 3B).

Myocardial infarction and heart failure

Among three comparisons in 6167 patients, 259 patients had myocardial infarction during follow-up. Meta-analysis showed no clear prevention of myocardial infarction of high-intensity statin in patients with CKD with low evidence when compared to non-intensive statin or placebo (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.18) (figure 3C). Myocardial infarction was reported in 252 patients from three trials. The analysis result showed that there was no significant difference between the two groups and indicated that high-intensity statin therapy had no superiority in reducing the incidence of heart failure (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.13) (figure 3D).

Effects on lipid levels and renal function

Information about the effect of high-intensity statin therapy on reducing the level of LDL-C was available in four included trials. In a Treating to New Targets (TNT) trial, the mean change of LDL-C levels from baseline to follow-up attained at the final visit with atorvastatin 80 mg versus atorvastatin 10 mg was −17.5 and 2.7 mg/dL, respectively, in patients with CKD. Similarly, data from the JUPITER trial demonstrated that rosuvastatin 20 mg could reduce the level of LDL-C to a larger degree (nearly −50 mg/dL) in patients with CKD. In addition, the SPARCL trial reported that high-intensity statin therapy had better effects on reducing the degree of LDL-C (from 134.4 mg/dL to 79.6 mg/dL) in comparison with placebo (from 134.3 to 121.9 mg/dL). The same results were also found in the PANDA trial, in which the adjusted mean difference between the high-dose and low-dose groups during follow-up was −0.6 (p<0.001). In conclusion, high-intensity statin therapy had an excellent effect on lowering the level of LDL-C.

Meta-analysis conducted with data from three trials demonstrated that high-intensity statin showed no strong superiority in increasing eGFR with high evidence (WMD 1.09, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.82) (figure 3E). However, two other trials which also gave out the information about eGFR change had an opposite opinion. The JUPITER trial reported that among the patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline, the median eGFR levels at 12 months were 53.0 vs 52.8 mL/min/1.73 m2 (p=0.44). The PANDA trial also reported that after adjusting for baseline renal function and other covariates (baseline age, gender, renal function, smoking, etc), there were no significant between-group differences during follow-up in any measure of renal function. Throughout the five trials, only the PANDA trial gave out detailed information about other renal function measurements, including the albumin:creatinine ratio, serum creatinine, cystatin C, creatinine clearance, albumin excretion and excretion. All data showed that there was no evident association between high-intensity statin therapy and renal protection. Therefore, it was quite difficult to draw conclusions on the effect of high-intensity statin on renal function and more evidences with high quality are needed to illustrate it.

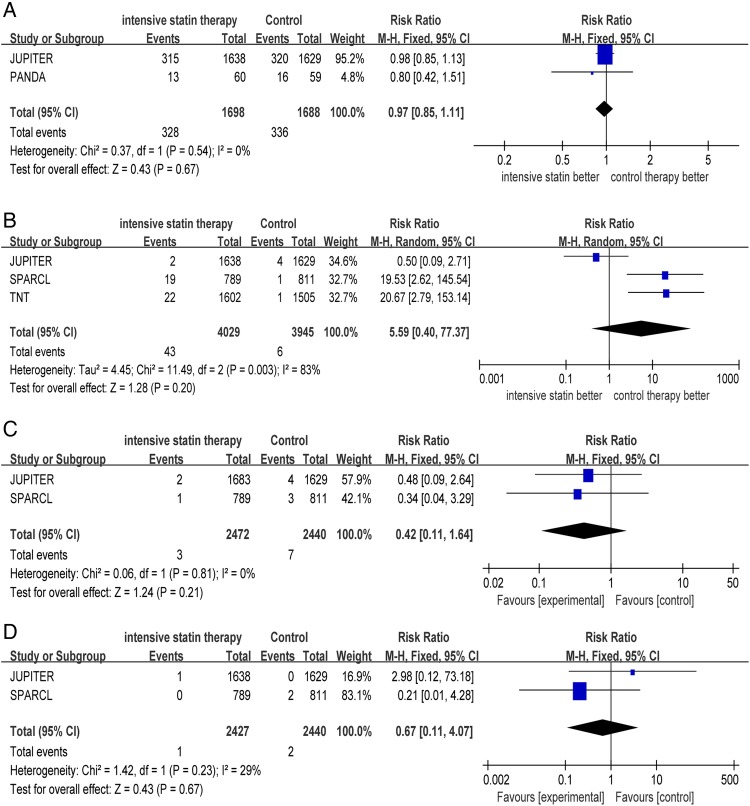

Safety evaluation

Data on any serious adverse event were available in four trials. As depicted in figure 4A, 664 patients had suffered from any serious event. The meta-analysis results demonstrated that high-intensity statin therapy had no clear association with increased incidence of any serious adverse event (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.11). Information about the rate of persistent elevation of liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase was available in three trials. Although the total incidence rate was much higher in the high-intensity statin group (1.1% vs 0.15%), pooled analysis illustrated no significant difference between the two groups (RR 5.59, 95% CI 0.40 to 77.37) (figure 4B). Myopathy and rhabdomyolysis only happened in 10 and 3 patients, respectively, in patients with CKD, and as illustrated in figure 4C,D, intensive statin also had an unclear relationship with increased incidence of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis when compared with placebo (for myopathy, RR=0.42 and 95% CI 0.11 to 1.64; for rhabdomyolysis, RR=0.67 and 95% CI 0.11 to 4.07). In addition, only one patient was detected to suffer from abnormality of creatine phosphokinase with the data extracted from the TNT, ALLIANCE and SPARCL trials. However, although the incidences of adverse events were very low and pooled results showed no significant difference between the intervention and control groups, it was still insufficient to put off the doubts that high-intensity statin might increase adverse events because very few included trials gave out the data of every individual adverse event and the evidence quality of most pooled results was not high.

Figure 4.

Forest plots for safety evaluation of intensive statin therapy for patients with CKD: any serious adverse event (A), persistent elevation of AST/ALT (B), myopathy (C), rhabdomyolysis (D). CI, confidence intervals; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Discussion

The present study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of high-intensity statin therapy in persons with CKD. Although previous meta-analyses had demonstrated that statin therapy could safely play a role in preventing cardiac mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with CKD, we only observed an advantage of high-intensity statin therapy in decreasing the incidence of stroke in our meta-analysis. However, its effect of preventing all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction and heart failure remains unclear with low evidence. More large trials with high quality are needed to explore the effect of high-intensity statin therapy on clinical outcomes. After carefully reviewing the data about the level changes of LDL-C and eGFR, we found that high-intensity statin had obvious effects on lowering the LDL-C level but no clear effects on renal protection. When we come to safety evaluation, the occurrences of most of the adverse events are very low and pooled results showed no significant difference between high-intensity statin therapy and non-intensive statin therapy or placebo in any serious adverse event, persistent elevation of liver enzymes, myopathy and rhabdomyolysis. However, with limited data source and low quality evidence, the results of safety evaluation in our study remain controversial and more trials with high-quality evidence are needed to detect high-intensity statin's adverse effects in patients with CKD.

In the treatment of atherosclerotic vascular disease, statins have already surpassed all other classes of medicines in reducing the incidence of the major adverse outcomes of death, heart attack and stroke.25 Current guidelines recommend that high-intensity statin therapy should be initiated for adults ≤75 years of age with clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who are not receiving statin therapy and that the intensity should be increased in those who receive a low-intensity or moderate-intensity statin therapy, unless they have a history of intolerance to high-intensity statin therapy or other characteristics that may influence safety. However, the evidence of high-intensity statin use in adults with CKD was insufficient.16 Several recent overviews and meta-analyses consistently suggested benefits from statin therapy in persons with CKD, but they did not focus on the efficacy and safety of high-intensity statin therapy.10–15 26 In our meta-analysis, although high-intensity statin therapy showed no clear benefit in decreasing the incidence of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction and heart failure in persons with CKD, its role in reducing the incidence of stroke was well established with high quality evidence.

Several studies have shown that eGFR and albuminuria are associated with incident CVD, coronary heart disease, stroke and heart failure events in varying populations.27 28 In our systematic review, we have carefully evaluated the effect of high-intensity statin therapy on the eGFR level to clarify the puzzle whether it has partial cardiovascular protection through increasing eGFR in patients with CKD. Unfortunately, we find no clear relationship between high-intensity statin therapy and increased eGFR levels. This situation may be ascribed to the long treatment duration, as a meta-analysis enrolling 20 trials and 6452 patients with CKD demonstrated that glomerular filtration rate depended on treatment duration—a significant increase was observed between 1 and 3 years of statin therapy, with no significant increase for both<1 and >3 years of the therapy.29 Only one of six trials gave out the information about the change of albuminuria level in this review, and therefore its result was insufficient to cover the whole population. As a result, more high quality evidences are needed to explore the renal protection effects of high-intensity statin in patients with CKD.

With functional or structural abnormalities of the kidney, patients with CKD are considered to be more vulnerable to high-dose or intensive drug application than the general population, because of reduced renal excretion, frequent polypharmacy and high prevalence of comorbidity in this population. However, in this study, we could not observe significant differences in all of the safety evaluation between the high-intensity statin therapy and control groups. The same results have also been found in a meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy and safety of high-intensity statin therapy in patients with CVD with age more than 65 years, which is a risk factor for CKD and also an inhibiting factor for high-dose or intensive drug application.30 These results give us more confidence in high-intensity statin therapy's safety application in patients with CKD.

The current guideline (KDIGO) recommends statin initiation in adults with eGFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 but not requiring dialysis and renal transplant. However, it does not give out detailed information about the recommended dose. So, we want to clearly determine what strength of statin therapy is more effective. In the five trials which have reported the clinical events, only one trial (JUPITER trial) was designed to compare the effects of high-intensity statin with placebo, whereas all the other four trials were designed to compare atorvastatin 80 mg with moderate or mild-intensity statin treatment. After abandoning the data from JUPITER, the pooled analysis still showed consistent results in all-cause mortality, stroke and myocardial infarction in patients with CKD.

Limitations

Our review also has some limitations. First, our study lacks high-quality primary studies and most trials included are post hoc studies. Second, there are only six trials included in our meta-analysis, and the small sample size and few reported end points may have an influence on the power of this study. Third, since most patients enrolled in this analysis had moderate CKD, the available evidences are not suitable for patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (GFR categories G1–G2), end-stage renal disease and haemodialysis.

Conclusion

High-intensity statin therapy could effectively reduce the risk of stroke in patients with CKD. However, its effects on all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, heart failure and renal protection remain unclear. Also, it is hard to draw conclusions on the safety assessment of intensive statin treatment in this particular population. More studies are needed to credibly evaluate the effects of high-intensity statin therapy in patients with CKD.

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-LY participated in the study design, literature search, data extraction, data analysis and paper writing. BQ mainly participated in the study design, literature search and data extraction and also helped in paper writing. JW was involved in data extraction and data analysis. S-BD participated in the study design and paper revision. LW helped a lot in data analysis. X-DJ helped with data analysis. J-LD mainly took part in the study design. Y-JL helped with the paper writing. QS participated in the study design and helped with the literature search and data extraction when needed. He also helped greatly with the paper revision.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC et al. . Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2003;108:2154–69. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095676.90936.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinkau T, Hilgers KF, Veelken R et al. . How does minor renal dysfunction influence cardiovascular risk and the management of cardiovascular disease? J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:517–23. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000107565.17553.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D et al. . Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascularevents, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1296–305. 10.1056/NEJMoa041031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jungers P, Massy ZA, Nguyen Khoa T et al. . Incidence and risk factors of atherosclerotic cardiovascular accidents in predialysis chronic renal failure patients: a prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997;12:2597–602. 10.1093/ndt/12.12.2597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyre AD, Fox CS, Astor BC et al. . The impact of reclassifying moderate CKD as a coronary heart disease risk equivalent on the number of US adults recommended lipid-lowering treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2007;49:37–45. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Berg K et al. . Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91755-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.[No authors listed] Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349–57. 10.1056/NEJM199811053391902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heart protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills EJ, O'Regan C, Eyawo O et al. . Intensive statin therapy compared with moderate dosing for prevention of cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of >40 000 patients. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1409–15. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strippoli GF, Navaneethan SD, Johnson DW et al. . Effects of statins in patients with chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 2008;336:645–51. 10.1136/bmj.39472.580984.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer SC, Craig JC, Navaneethan SD et al. . Benefits and harms of statin therapy for persons with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:263–75. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Upadhyay A, Earley A, Lamont JL et al. . Lipid-lowering therapy in persons with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:251–62. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou W, Lv J, Perkovic V et al. . Effect of statin therapy on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: asystematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1807–17. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Xiang C, Zhou YH et al. . Effect of statins on cardiovascular events in patients with mild to moderate chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014;14:19 10.1186/1471-2261-14-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navaneethan SD, Pansini F, Perkovic V et al. . HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD007784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonelli M, Wanner C, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Lipid Guideline Development Work Group Members. Lipid management in chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2013 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:182 10.7326/M13-2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepherd J, Kastelein JJ, Bittner V et al. . Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease: the TNT (treating to new targets) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1448–54. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koren MJ, Davidson MH, Wilson DJ et al. . Focused atorvastatin therapy in managed-care patients with coronary heart disease and CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:741–50. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holme I, Fayyad R, Faergeman O et al. . Cardiovascular outcomes and their relationships to lipoprotein components in patients with and without chronic kidney disease: results from the IDEAL trial. J Intern Med 2010;267:567–75. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02176.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridker PM, MacFadyen J, Cressman M et al. . Efficacy of rosuvastatin among men and women with moderate chronic kidney disease and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: a secondary analysis from the JUPITER (Justfication for the Use of Statins in Prevention-an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1266–73. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutter MK, Prais HR, Charlton-Menys V et al. . Protection against nephropathy in diabetes with atorvastatin (PANDA): a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of high- vs. Low-dose atorvastatin. Diabetes Med 2011;28:100–8. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amarenco P, Callahan A, Campese VM et al. . Effect of high-dose atorvastatin on renal function in subjects with stroke or transient ischemic attack in the SPARCL trial. Stroke 2014;45:2974–82. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pellicori P, Costanzo P, Joseph AC et al. . Medical management of stable coronary atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2013;15:313 10.1007/s11883-013-0313-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deedwania PC. Statins in chronic kidney disease: cardiovascular risk and kidney function. Postgrad Med 2014;126:29–36. 10.3810/pgm.2014.01.2722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drury PL, Ting R, Zannino D et al. . Estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria are independent predictors of cardiovasular events and death in type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) Study. Diabetologia 2011;54:32–43. 10.1007/s00125-010-1854-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hillege HL, Janssen WM, Bak AA et al. . Microalbuminuria is common, also in a nondiabetic, nonhypertensive population, and an independent indicator of cardiovascular factors and cardiovascular morbidity. J Intern Med 2001;249:519–26. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikolic D, Banach M, Nikfar S et al. . A meta-analysis of the role of statin on renal outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. Is the duration of therapy important? Int J Cardiol 2013;168:5437–47. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan YL, Qiu B, Hu LJ et al. . Efficacy and safety evaluation of intensive statin therapy in older patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013;69:2001–9. 10.1007/s00228-013-1570-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]