Abstract

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide, with 1.3 million new cases diagnosed every year. It has one of the lowest survival outcomes of any cancer because over two-thirds of patients are diagnosed when curative treatment is not possible. International research has focused on screening and community interventions to promote earlier presentation to a healthcare provider to improve early lung cancer detection. This paper describes the protocol for a phase II, multisite, randomised controlled trial, for patients at increased risk of lung cancer in the primary care setting, to facilitate early presentation with symptoms of lung cancer.

Methods/analysis

The intervention is based on a previous Scottish CHEST Trial that comprised of a primary-care nurse consultation to discuss and implement a self-help manual, followed by self-monitoring reminders to improve symptom appraisal and encourage help-seeking in patients at increased risk of lung cancer. We aim to recruit 550 patients from two Australian states: Western Australia and Victoria. Patients will be randomised to the Intervention (a health consultation involving a self-help manual, monthly prompts and spirometry) or Control (spirometry followed by usual care). Eligible participants are long-term smokers with at least 20 pack years, aged 55 and over, including ex-smokers if their cessation date was less than 15 years ago. The primary outcome is consultation rate for respiratory symptoms.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from The University of Western Australia's Human Research Ethics Committee (RA/4/1/6018) and The University of Melbourne Human Research Committee (1 441 433). A summary of the results will be disseminated to participants and we plan to publish the main trial outcomes in a single paper. Further publications are anticipated after further data analysis. Findings will be presented at national and international conferences from late 2016.

Trial registration number

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry ACTRN 1261300039 3752.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, PUBLIC HEALTH, ONCOLOGY, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The CHEST-Australia Trial represents the first trial in Australia to test this type of intervention and measure its impact on health care consultations.

The trial builds on preliminary evidence from the Scottish CHEST Trial, which showed promising results for altering symptom appraisal and help-seeking behaviour.

Information from this trial will enable planning of a larger phase III international trial to further assess the impact of the CHEST Intervention on clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the commonest cancer worldwide;1 in Australia, there were 11 280 new cases and 8099 deaths due to lung cancer in 2010, making it the leading cause of cancer death.2 Lung cancer ranks second for men and fourth for women when considering all causes of death. This reflects its relatively high incidence (58 per 100 000 for males and 31 per 100 000 for females), which is still rising in women, and its low relative survival, only 7.8% of males and 9.3% of females survive beyond 5 years.3 4

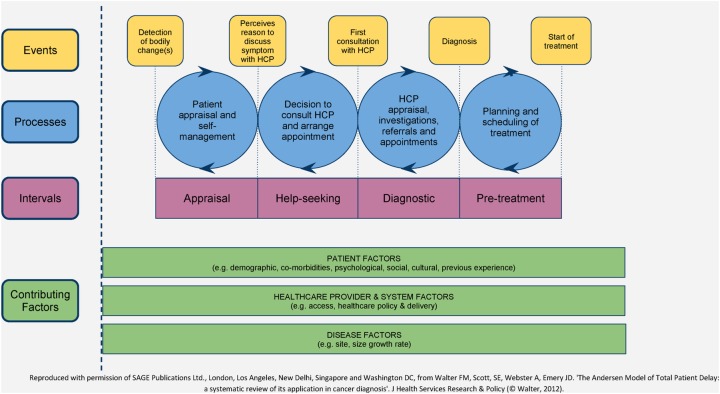

There is extensive literature spanning several decades on the concept of ‘diagnostic delay’ in cancer.5 6 This recognises that patient pathways to presentation to healthcare and initial management in primary care are key determinants of cancer patient outcomes.7 8 Much of the research on cancer diagnostic delay has suffered from lack of a theoretical model and precise definitions of key time points along the diagnostic pathway. Walter et al9 published a systematic review of cancer diagnostic studies that applied the Andersen Model of Total Patient Delay.10 On the basis of their review, they have modified this theoretical framework, producing The Model of Pathways to Treatment (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Model of pathways to treatment.

The model proposes four key intervals:

The Appraisal Interval. The review found that the nature of the symptoms was the most important factor determining the duration of the Appraisal Interval. Misattribution of symptoms either to a previous benign or concurrent condition or non-recognition of the seriousness of symptoms contribute to longer Appraisal Intervals.11

The Help-Seeking Interval. Various factors may contribute to this interval including patient factors such as competing events (eg, holidays), and emotional ones such as fear. This includes fear of the consultation and examination, or of the diagnosis and treatment.12 Access to primary care and sanctioning help-seeking by family or friends, so that patients do not perceive themselves as wasting the doctor's time, are also important factors.12

The Diagnostic Interval. Depending on the healthcare setting, this may involve a series of healthcare visits, referrals and investigations, and often represents a complex process. System factors including the role of primary care as a gatekeeper, and access to investigations and specialist care, are key factors determining this interval.9

The Pre-Treatment Interval. The time from formal cancer diagnosis to initiation of treatment is also strongly influenced by several healthcare system factors such as access to staging investigations and specialised treatments.

Several studies have explored symptom appraisal and help-seeking in people recently diagnosed with lung cancer. Two studies of lung cancer patients from Western Australia have found that normalisation of respiratory symptoms is very common with mean patient delays to seek help of 47–80 days, respectively.13 14 Campbell and colleagues15 interviewed 360 Scottish patients with lung cancer; of these, 50% had experienced symptoms for more than 14 weeks before presenting to a doctor (median 99 days; IQR 31–381 days). The duration of these patient delays should be compared with reported lung cancer median volume doubling times of 98 days.16 Factors associated with longer symptom appraisal and help-seeking included living alone, a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and longer pack years of smoking. In contrast, haemoptysis, new onset of shortness of breath and cough were associated with earlier consulting. Another English study had similar findings: most patients recalled having symptoms for many months before seeking help, but these symptoms were not recognised as serious, were attributed to everyday causes, and therefore not acted on.17 18 There was reluctance to seek help among some people, partly because they were unsure whether their symptoms were normal and, for some, because of the stigma associated with smoking. Furthermore, patients may not discuss all their symptoms of lung cancer when they do visit their general practitioner (GP), suggesting patients need to be empowered to recognise the significance of symptoms and report them to healthcare providers.19 Patients may also need clear guidance on reasons to revisit their GP if their symptoms persist, an important safety-netting function of general practice.20

Further evidence for the potential to improve lung cancer outcomes by earlier diagnosis comes from the US National Lung Cancer Screening Trial, which found a 20% relative reduction in lung cancer mortality from annual low-dose CT.21 However, the uncertain cost-effectiveness and feasibility of implementing national lung cancer screening programmes means that other approaches to timely diagnosis of lung cancer are still needed. The search for useful biomarkers of lung cancer shows promise, but is still at the validation stage,22 suggesting an alternative strategy is to attempt to diagnose lung cancer earlier through prompt recognition and investigation of symptoms suggestive of the disease, particularly in those at higher risk.

Public awareness campaigns for educating patients on symptom awareness have shown promise, but many have limited reporting outcomes. Lung cancer ‘signs and symptoms’ intervention studies such as ‘Show us your lungs’ (Australia),23 ‘Be clear on Cancer (UK),24 ‘I'll tackle it soon’ (UK),25 aimed to raise awareness of the signs and symptoms of lung cancer, and promote help seeking behaviour. The ‘I'll tackle it soon’ study showed that a combined public awareness campaign and GP education programme led to increased chest X-ray referrals by 20% and lung cancer diagnoses by 27%.25

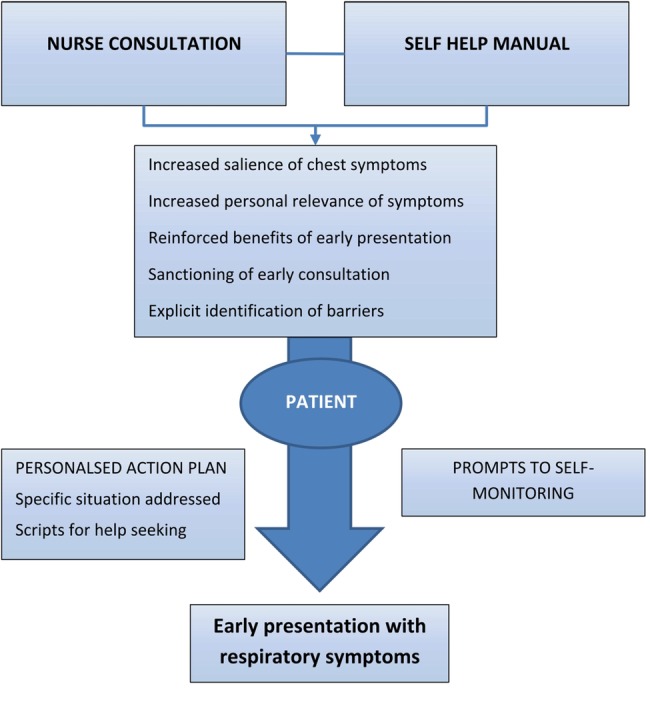

While patient level interventions show promise in increasing cancer awareness,26 there has been limited research on interventions delivered to individuals at increased risk of lung cancer aimed at promoting earlier presentation to healthcare. The Chest Trial in Scotland was the first to show preliminary evidence that this approach could alter consulting patterns in this population.27 28 In this trial, a theoretically-based intervention, which comprised of a primary-care nurse consultation to discuss and implement a self-help manual, was tested, followed by self-monitoring reminders. The key objectives of the intervention were as follows, with the relevant underlying theories in parentheses: (1) Increase the salience and personal relevance of symptoms (Illness Action Model29). (2) Improve knowledge of symptoms by introducing chest disease prototypes (Illness Action Model and Illness prototypes29 30). (3) Reinforce the benefits of early intervention in lung cancer and other chest disease (Theory of Planned Behaviour31 32). (4) Sanction early consultation (Zola's triggers33). (5) Tackle barriers to consultation (Theory of Planned Behaviour31 32). (6) Develop personalised action and coping plans (Social Cognitive Theory and Implementation Intentions).34 35 Intervention components 1 and 2 aim to reduce the Symptom Appraisal Interval, while components 3–6 aim to reduce the Help-Seeking Interval. Based on consumer feedback the intervention was designed specifically without any mention of smoking cessation, which was seen as a barrier to engagement. Furthermore, the focus was on chest disease broadly, including the early detection of lung cancer, COPD and other chronic respiratory conditions. This was to reduce potential effects of fear and nihilism surrounding lung cancer.36 Figure 2 presents a summary of the intervention.

Figure 2.

Intervention summary.

Two hundred and twelve people at increased risk of lung cancer were recruited into the Scottish CHEST Trial, of whom 206 completed the trial after 1 year of follow-up (102 intervention, 104 control). The total consultation rate was significantly higher in the intervention group (adjusted consultation ratio 1.15, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.27 p=0.005) with a median number of consultations in the year after intervention of 8 (IQR 4–11). The adjusted consultation ratio for new chest symptoms also increased but this did not reach statistical significance (ratio 1.19, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.53). Participants in the intervention group intended to consult sooner with symptoms. There were non-significant increases in chest X-ray requests and referrals to respiratory medicine in the intervention group.27

The Scottish CHEST Trial therefore provides important preliminary evidence for the potential efficacy of the intervention in altering symptom appraisal and help-seeking behaviour. However, stronger evidence is required before this research can inform practice and policy. In particular, evidence is required on the generalisability of the intervention in other populations and the effect on clinical outcomes as well as consulting behaviours.

Preliminary phase I research in Australia with consumer focus groups was conducted to review the CHEST self-help manual and provide feedback on the overall intervention. In addition, the intervention was piloted on 11 participants recruited from a general practice in Perth, Western Australia. This work resulted in modifications to the language used in the consultation and self-help manual, and led to the development of the CHEST Australia Trial: a phase II, multisite, randomised controlled trial that aims to test the modified CHEST Intervention in an Australian population and measure the effect of the intervention on consultation rates for chest symptoms.

Methods and analysis

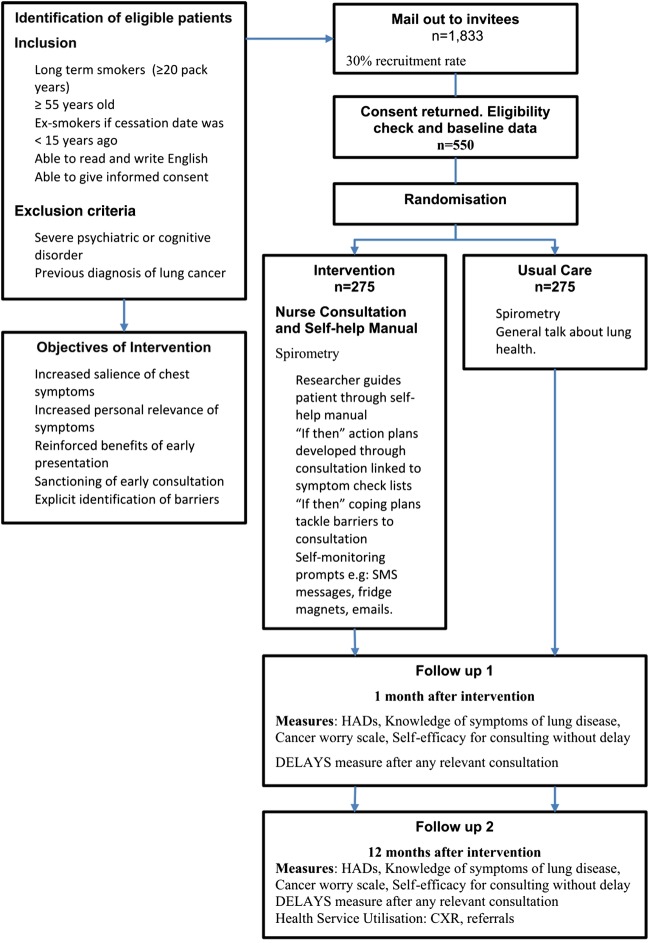

The phase II trial is a multisite randomised controlled trial. Those who meet the eligibility criteria and who consent to participate are randomised 1:1 to either usual care (control arm) or to the intervention (figure 3). Randomisation is being performed using a centralised independent tele-randomisation system managed by the NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, based at the University of Sydney. Stratifying variables for randomisation are MRC dyspnoea score (scores 1–3 and 4–5) and general practice recruitment site.

Figure 3.

Trial flowchart.

Population and setting

Participants are being recruited from general practices in Perth (Western Australia) and Melbourne (Victoria). Recruitment began in May 2013 and aims to be completed in mid-2015.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible participants are long-term smokers with at least 20 pack years, aged 55 and over, including ex-smokers if their cessation date was less than 15 years ago. This represents a population at increased risk of lung cancer.20 Participants are able to read and write English, and to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria are severe psychiatric or cognitive disorder or previous diagnosis of lung cancer.

Participant and recruitment procedures

Smokers and ex-smokers are identified from practice computerised records using a specific version of electronic data extraction software, the ‘Canning tool’ (http://www.canningtool.com.au), developed for this trial. Potentially eligible patients are invited to participate in the study by letter from their general practice. The invitations include a patient information sheet, ‘expression of interest form’ and a consent form. The expression of interest form asks four screening questions aimed at assessing smoking pack years. These screening questions provide more accurate information regarding the eligibility of patients and overcome limitations of electronic data on smoking in the medical record. Non-responders are followed up after 2 weeks with a reminder postcard. Eligible patients returning an expression of interest form are followed up by phone to make an appointment with a health researcher at their general practice. Randomisation is performed after completion of baseline data and informed consent has been obtained.

Intervention

The Self-Help Manual, entitled ‘Chest Symptoms that Call for Action’, is based around a simple action plan logo, ‘It's as easy as 1, 2, 3’. These three key actions are:

Look after number one and know the symptoms of lung disease.

It takes two to tango: doctors can only help you if you see them when you have symptoms.

Remember the 3-week rule and see your doctor if you have symptoms for more than 3 weeks.

Participants randomised to the intervention arm have their height, weight and spirometry (using an ‘Easy on PC’; Niche Medical) measured at the consultation. The results of the spirometry test are sent to the GP at the end of the consultation. The trained researcher then guides the patient through the self-help manual, which is taken home by the participant. ‘If-then’ action plans are developed during the consultation which is linked to symptom checklists; ‘If-then’ coping plans are discussed to tackle barriers to consultation. A range of monthly self-monitoring prompts to appraise any current symptoms are tailored to individual preferences. These include SMS and email reminders, postcards, phone calls and fridge magnets. To ensure trial fidelity, intervention consultations are recorded for quality assurance.

Control group

Participants randomised to the control arm attend a consultation where they perform a spirometry test, and follow-up procedures in the trial are discussed. There is also a general discussion about lung health. This is aimed as an attention control and to increase overall engagement in the trial for control participants. Participants then receive usual care at their general practice, including follow-up of abnormal spirometry.

Outcomes and measures

The primary outcome of this trial is consultation rates for respiratory symptoms. Data on consultations in the year before the trial and for 12 months after the consultation will be collected through audit of GP records.

Additional outcomes include

Demographics and clinical variables. Age, gender, marital status, postcode, highest education level, occupation, MRC Dyspnoea Scale37 and lung function at baseline only.

Self-efficacy for consulting without delay. A 10-item self-completed scale summed to score 10–100, developed for the Scottish CHEST Trial, which showed good internal reliability (Cronbach α=0.85).

Knowledge of symptoms of lung disease. A 21-item self-completed checklist of possible symptoms expressed as a percentage correctly selected as associated with chest disease.

Symptom appraisal and help-seeking intervals. This will be measured using the SYMPTOM instrument (lung cancer version), a self-completed questionnaire that obtains data on presenting symptoms and their duration prior to consultation.38 This will be measured monthly during the trial through electronic searches of the GP records. If a consultation has occurred about a respiratory symptom in that timeframe, the participant is sent a SYMPTOM questionnaire to complete about symptoms relating to that consultation.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS).39 This 14-item self-completed scale has been widely used to measure distress, and has been extensively validated and shown to perform well in a wide range of populations (mean Cronbach α=0.82; sensitivity and specificity 0.80).

Cancer-worry scale. A 6-item self-completed scale, adapted from the breast cancer worry scale,40 which showed good internal reliability in the CHEST Trial (Cronbach α=0.88).

Quality of life will be measured using the AqoL-8d,34 a validated self-completed, multi-attribute utility measure that can be used as part of the health economic evaluation of the intervention. This 35-item scale covers the following domains: independent living, happiness, mental health, coping, relationships, self-worth, pain and senses.

Heath service utilisation. In addition to the primary measure of consultation rates for respiratory symptoms, data relating to total general practice consultation rates, chest X-ray requests and referrals to respiratory physicians, will also be captured through audit of general practice records. Participants consent to access to their Medicare claims data (including pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS) and Medicare benefits schedule (MBS)) through the Department of Human Services. This will provide more complete data relating to visits to other general practices (and investigations and referrals arising from these) as well as prescribing data.

Lung cancer incidence. This will be identified through GP medical records, and by flagging participants with the WA and Victorian Cancer Registries.

Trial feasibility and acceptability. As a phase II trial we will also obtain data on patient recruitment and attrition, and response rates to outcome measures, to inform decisions about a future phase III trial.

Measurement timing

The participant-completed measures (1–7 above) are taken at baseline, 1 and 12 months, with the exception of the SYMPTOM instrument, as already described. Health service utilisation data will be collected at 12 months by general practice medical record audit and accessing Medicare and PBS data. This data will not be collected for participants who formally withdraw from the trial.

Participant data and study management

All participants are allocated a unique identifying code. Questionnaire data are entered into a custom built Oracle database (on a secure server held at the University of Western Australia) to allow scoring of the measures in the questionnaire and enable patient tracking through the study.

Sample size and power calculation

Data from the Scottish trial was used to inform power calculations.28 Assuming that the primary end point of consultations for respiratory symptoms follows a Poisson distribution, and that the expected average rate over 12 months in the study population will be 1.06 for control patients and 25% higher for intervention patients, a sample of 534 will provide at least 80% power to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between the groups at the two-sided 5% level of significance. The primary end point will be measured from the medical record audit, thus minimising attrition. Accounting for the same attrition rate observed in the Scottish trial, we require a total sample of 550 participants.

Analyses

All randomised patients will be considered eligible for inclusion in the analysis in accordance with the intention to treat analysis principle. Appropriate methods for dealing with missing end point data will be addressed and informed by a blinded review of the data. The baseline characteristics of the two arms will be described using summary statistics. Possible consent bias will be assessed by comparing demographic and clinical variables of participants against those who declined participation, and possible differential attrition will be assessed by comparing baseline characteristics of those who withdraw or die against those who remain in the study. These comparisons will be performed using a two sample t test (or non-parametric equivalent) for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. The primary analysis will be a comparison between the two groups on consultations rate for respiratory symptoms using a Poisson regression model, with general practice included as a factor. Comparisons between groups on continuous secondary end points will be undertaken using a linear model that includes general practice as a factor and the baseline value as a covariate (where applicable). Comparisons between groups on categorical secondary end points will be performed using logistic regression with general practice fitted as a factor. The analyses performed on the primary and secondary end points will be repeated adjusting for additional baseline covariates (eg, number of consultations in 12 months prior to randomisation, gender, comorbidities, smoking status, MRC Dyspnoea Score) as part of a sensitivity analysis. Point estimates of the treatment effect will be presented with two-sided 95% CIs and two-sided p values. Unadjusted p values from secondary analyses are interpreted in proper context and will be clearly labelled.

The health economic analysis estimates the cost of CHEST minus any cost-savings due to avoided healthcare utilisation through early diagnosis. Benefits will be extrapolated from the primary end points and via the AQOL-8D quality of life questionnaire. Results will be presented in terms of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. Many of these model parameters will not be powered for statistical significance. Therefore, mean estimates of resource utilisation will be used and CIs are generated by boot-strapping the data. Uncertainty will be explored using probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

The CHEST-Australia Trial represents the first trial in Australia to test this type of intervention and measure its impact on healthcare consultations. Information from this trial will enable planning of a larger phase III international trial to further assess the impact of the CHEST Intervention on clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This trial is supported by the Cancer Australia Primary Care Collaborative Cancer Clinical Trials Group (PC4). The authors thank Ian Peters for development of the Canning smoking tool and help with general practice recruitment in Perth. We are grateful to all trial participants and GP staff from Perth and Melbourne involved in the trial. Protocol V.1.1. 11 September 2014.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors assisted with the development of the protocol, study design and refinement of study materials. SRM assisted in development of the protocol and designed the Australian study materials. SRM implemented the trial, and oversees the protocol and collection of data in Perth. EH oversees the collection of data in Melbourne. SRM and JDE led the writing of the manuscript. All authors will contribute to implementation of the protocol and acquisition of data. All authors have been involved in critical evaluation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship eligibility guidelines have been followed and no professional writers have been used.

Funding: This trial is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. (NHMRC grant ID 1064121). The funding source has no role in the design of this study, the interpretation of data or decision to submit results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval has been obtained from The University of Western Australia's Human Research Ethics Committee (RA/4/1/6018) and The University of Melbourne Human Research Committee (1441433). There is no formal Data Monitoring Committee for this trial as it was felt unnecessary for this type of intervention. Data management procedures are reported to HREC. Interim analysis, stopping guidelines and protocol amendments are reported to HREC. Any significant changes are reported to the ANZCTR. Requests for the final dataset should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Data sharing statement: A summary of the results will be disseminated to the study participants. We plan to publish the main trial outcomes in a single paper. Further publications are anticipated after exploring the data in more detail relating to implementation of this complex intervention. Findings will be presented at national and international conferences from late 2016.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2014. http://globocan.iarc.fr (accessed 2 Oct 2014).

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Cancer Australia 2011. http://www.aihw.gov.au/cancer/cancer-in-australia/#deaths (accessed 2 Oct 2014).

- 3.Cancer Research UK. Lung cancer—survival statistics 2012. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/lung/survival/ (accessed 2 Oct 2014).

- 4.Wang T, Nelson RA, Bogardus A et al. . Five-year lung cancer survival: which advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer patients attain long-term survival? Cancer 2010;116:1518–25. 10.1002/cncr.24871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allgar VL, Neal RD. Delays in the diagnosis of six cancers: analysis of data from the National Survey of NHS Patients: cancer. Br J Cancer 2005;92:1959–70. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB et al. . Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet 1999;353:1119–26. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02143-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards MA. The size of the prize for earlier diagnosis of cancer in England. Br J Cancer 2009;101(Suppl 2):S125–9. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin G, Vedsted P, Emery J. Improving cancer outcomes: better access to diagnostics in primary care could be critical. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:317–18. 10.3399/bjgp11X572283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walter F, Webster A, Scott S et al. . The Andersen model of total patient delay: a systematic review of its application in cancer diagnosis. J Health Ser Res Policy 2012;10:1–13. 10.1186/1478-4505-10-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen BL, Cacioppo JT. Delay in seeking a cancer diagnosis: delay stages and psychophysiological comparison processes. Br J Soc Psychol 1995;34(Pt 1):33–52. 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brouha XD, Tromp DM, de Leeuw JR et al. . Laryngeal cancer patients: analysis of patient delay at different tumor stages. Head Neck 2005;27:289–95. 10.1002/hed.20146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith LKP, Pope C, Botha JL. Patients help-seeking experiences and delay in cancer presentation: a qualitative synthesis. Lancet 2005;366:825–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67030-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emery JD, Walter FM, Gray V et al. . Diagnosing cancer in the bush: a mixed-methods study of symptom appraisal and help-seeking behaviour in people with cancer from rural Western Australia. Fam Pract 2013;30:294–301. 10.1093/fampra/cms087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall SE, Holman CD, Threlfall T et al. . Lung cancer: an exploration of patient and general practitioner perspectives on the realities of care in rural Western Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16:355–62. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.01016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith SM, Campbell NC, MacLeod U et al. . Factors contributing to the time taken to consult with symptoms of lung cancer: a cross-sectional study. Thorax 2009;64:523–31. 10.1136/thx.2008.096560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Yip R et al. . Lung cancers diagnosed at annual CT screening: volume doubling times. Radiology 2012;263:578–83. 10.1148/radiol.12102489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corner J, Hopkinson J, Fitzsimmons D et al. . Is late diagnosis of lung cancer inevitable? Interview study of patients’ recollections of symptoms before diagnosis. Thorax 2005;60:314–19. 10.1136/thx.2004.029264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corner J, Hopkinson J, Roffe L. Experience of health changes and reasons for delay in seeking care: a UK study of the months prior to the diagnosis of lung cancer. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:1381–91. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brindle L, Pope C, Corner J et al. . Eliciting symptoms interpreted as normal by patients with early-stage lung cancer: could GP elicitation of normalised symptoms reduce delay in diagnosis? Cross-sectional interview study. BMJ Open 2012;2:pii: e001977 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birt L, Hall N, Emery J et al. . Responding to symptoms suggestive of lung cancer: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open Resp Res 2014;1:e000067 10.1136/bmjresp-2014-000067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD et al. . Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395–409. 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourzac K. Diagnosis: early warning system. Nature 2014;513: S4–6. 10.1038/513S4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Show us your lungs. Australia: Lung Foundation Research Australia, 2011. http://www.lungfoundation.com.au/showusyourlungs [Google Scholar]

- 24.Be clear on cancer. London: Cancer Research UK, 2011. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/spotcancerearly/naedi/beclearoncancer/lung/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Athey VL, Suckling RJ, Tod AM et al. . Early diagnosis of lung cancer: evaluation fo a community-based social marketing intervention. Thorax 2012;67:412–17. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austoker J, Bankhead C, Forbes LJ et al. . Interventions to promote cancer awareness and early presentation: systematic review. Br J of Cancer 2009;101:S31–9. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith S, Fielding S, Murchie P et al. . Reducing the time before consulting with symptoms of lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:47–54. 10.3399/bjgp13X660779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith SM, Murchie P, Devereux G et al. . Developing a complex intervention to reduce time to presentation with symptoms of lung cancer. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e605–15. 10.3399/bjgp12X654579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dingwall R. Aspects of illness. Burlington, USA: Ashgate Publishing, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bishop GD, Converse SA. Illness representations: a prototype approach. Health Psychol 1986;5:95–114. 10.1037/0278-6133.5.2.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behaviour. In: Beckman JKAJ, ed. Action control: from cognitions to behvior. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1985:11–39. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec 1991;50:179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zola IK. Pathways to the doctor-from person to patient. Soc Sci Med 1973;7:677–89. 10.1016/0037-7856(73)90002-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191–215. 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: a meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;38:69–119. 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ball DL, Irving LB. Are patients with lung cancer the poor relations in oncology? Med J Aust 2000;172:310–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R et al. . Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54:581–6. 10.1136/thx.54.7.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walter FW, Rubin G, Bankhead C et al. . Symptoms and other factors associated with time to diagnosis and stage of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer 2015;112(Suppl):S6–S13. 10.1038/bjc.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-8-657. Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, et al. Psychological and behavioral implications of abnormal mammograms. Ann Intern Med 1991;114:657–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]