Abstract

Simultaneous bilateral presentation of psoas abscess with prosthetic joint involvement is extremely rare. A 68-year-old woman presented to us with bilateral dull aching groin pain of 6 months’ duration, which flared up in the past month, associated with pyrexial symptoms. She had undergone bilateral hip replacements in the past with uneventful recovery. MRI showed bilateral psoas muscle collection in communication with the hip joints. Preoperative hip aspirate demonstrated frank pus with positivity on Gram stain and radiographs confirmed prosthetic loosening of bilateral hips. The patient subsequently underwent two-stage revision arthroplasty of both infected hip implants. At 5-year follow-up, the patient remains asymptomatic with good functional outcome and no recurrence on serial MRI.

Background

Psoas abscess is characterised by pus within the psoas muscle. Its incidence is about 0.4/100 000 in the UK.1 This condition may be either primary or secondary. From an aetiological point of view, although the cause of a primary abscess may be unknown, it is most likely due to haematogenous or lymphatic dissemination from a distant and occult infective focus. Nevertheless, HIV, diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug abuse, renal failure and other conditions of immune suppression, may all predispose the occurrence of a primary abscess.2

On the other hand, in a secondary abscess, the contamination usually comes directly from adjacent tissues infected. Specifically, an abscess of the psoas muscle may be associated with Crohn's disease, appendicitis, diverticulitis, ulcerative colitis, urinary tract infections, spondylodiscitis or an infection of the sacroiliac joint.3

Symptoms are often subtle and non-specific, making the diagnosis difficult and delayed. There is some evidence that septic hip arthritis may be associated with an abscess of the psoas muscle4–6 or following hip arthroplasty.7–10

Simultaneous bilateral presentation of psoas abscess with prosthetic joint involvement is unreported in the literature.

We report a case of a bilateral psoas abscess presentation likely secondary to concomitant prosthetic hip joint involvement, management and outcome.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old woman presented with a 6-month history of bilateral groin pain. She presented with constitutional symptoms, including fever, weight loss, night sweats, all worsened in the past month. Masses were palpable on either side of the groin. She underwent total hip arthroplasty of the left side in 1996, and of the right side in 2007. The patient also had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis, successfully treated in 1975 with isoniazid and rifampicin.

Investigations

Clinical examination to detect any focus of infection was negative. Abdominal ultrasound was negative. Haemocultures were sterile. Serum infective markers were raised. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 66 mm/h (0–29), PCR was 156 mg/L (0–6.00) and white cell count was 15.18×109/L (4.40–11). Blood and urine cultures were negative. The patient was immunocompetent. Chest radiograph was normal.

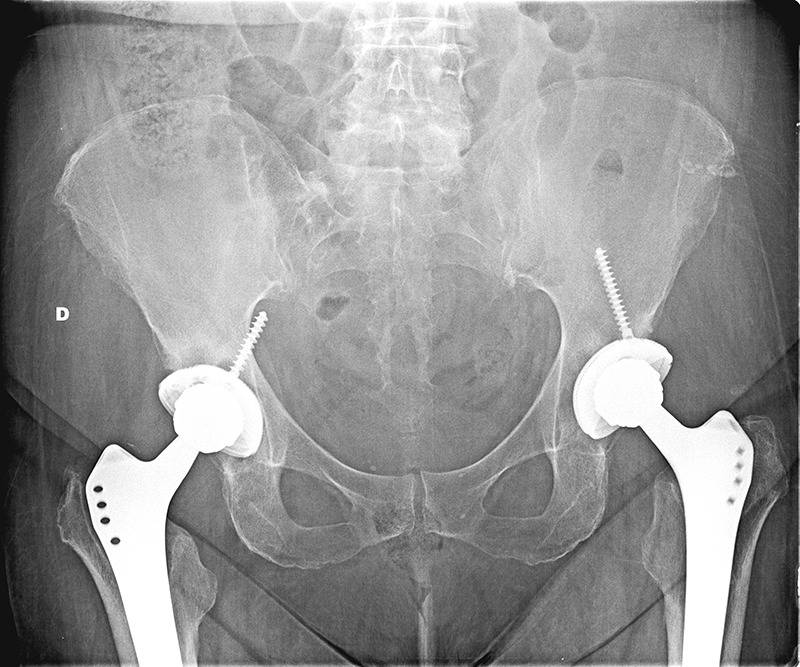

Hip radiographs demonstrated lucencies along both the acetabulum that were suggestive of loosening (figure 1). MRI of the lumbar spine excluded intervertebral discitis.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior radiograph showing loosening of the acetabular implants. On the right side, evidence of the acetabular screw perforating the iliac bone.

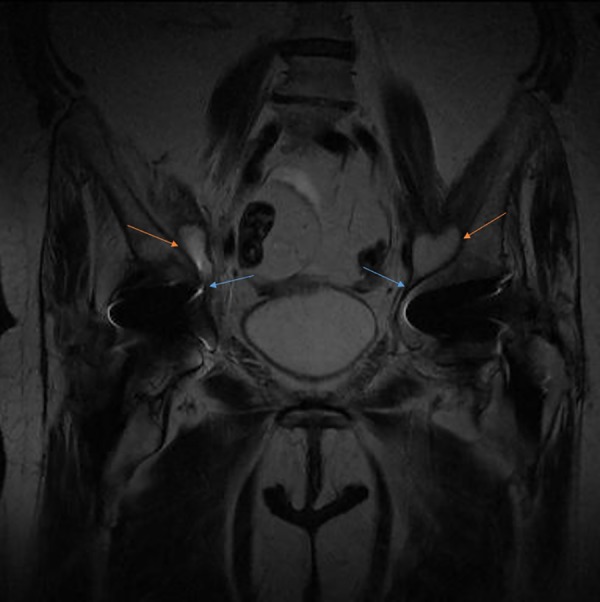

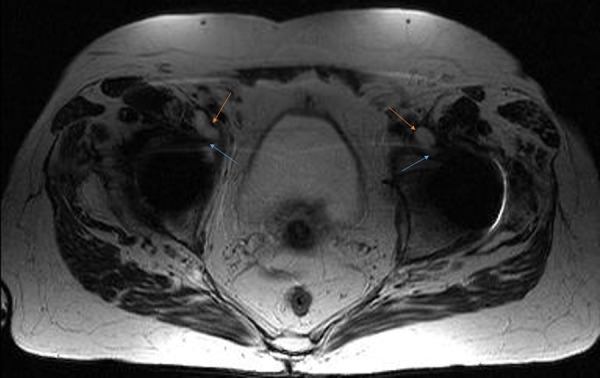

MRI assessment of the abdomen and pelvis showed abscesses along the psoas muscle bilaterally, extending to the hip joints (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

MRI coronal section of the pelvis showing a bilateral abscess of the psoas muscle in communication with the hip (orange arrows highlight the abscesses and blue arrows show communications with the joints).

Figure 3.

MRI axial section of the pelvis showing a bilateral abscess of the psoas muscle in communication with the hip (orange arrows highlight the abscesses and blue arrows show communications with the joints).

A joint aspiration of both the hip joints was carried out before proceeding with surgery. Cultures were sent for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, and, due to the pervious tuberculosis infection, acid-fast bacilli stain and Lowenstein culture were used.

Treatment

A two-stage revision procedure was undertaken bilaterally at an interval of 10 days. We used a lateral direct approach (Hardinge's approach) for both hips, which had been the previous access for primary. The implants were loose and it was easier to remove both femoral and acetabular components. After the removal of the cup and due to anterior acetabulum deficiency, the access to the iliac muscle was easier. The purulent material was drained from the bursa of the psoas and hip joint. After thorough exploration and debridement, we used a static Gentamycin-impregnated hand-made spacer. Significant bone loss was found on the anterior wall of both hip joints.

Ten days later, the same procedure was undertaken on the other joint: a massive collection of pus was drained, the prosthesis was removed and an antibiotic loaded spacer was implanted.

Culture grew Streptococcus anginosus species in the samples from both hips. The patient was started on intravenous antibiotic therapy (ceftriaxone sodium) for 6 weeks.

In the interval period, serial testing for infective markers was carried out, which showed a declining trend. The patient was treated on antibiotics for 6 weeks. Two weeks later both hips were aspirated with negative cultures. Repeat MRI showed resolution of the abscess.

The patient was taken up for a staged total hip replacement with an interval of 2 weeks.

The acetabulum on both sides showed significant bone loss medially and hence cages were used with cementless cup fixation. Long uncemented stems were implanted on the femoral side.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient had an uneventful postop recovery.

At the most recent follow-up at 5 years, the patient continued to be asymptomatic. She had good functional range of movements at both the hips with a Harris Hip Score of 77.85 on the right and 77.2 on the left, with normal radiographs (figure 4) and good functional outcome.

Figure 4.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the right (1) and left sides (2) 5 years after the revision procedure.

Discussion

Mynter reported the first case of abscess of the psoas muscle, referred to as psoitis, in 1881. Typical symptoms are back pain, fever and limp,2 present only in 30% of patients,2 but general symptoms may mask this condition, delaying diagnosis and management.

Staphylococcus aureus is the main cause of abscess, with an increased incidence of methicillan resistant S. aureus over the past few years2. The presentation of this case is unusual. S. Anginosus was isolated, a pathogen normally present in the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract. It can cause local abscesses, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis and septic shock.11

We speculate that the psoas infection was likely secondary. The association between psoas abscess and hip infection may be better explained assessing the anatomical features of the iliopsoas bursa, a synovial structure that lies between the tendon insertion of the psoas muscle and its insertion site, the lesser trochanter. As showed in a cadaveric study, the infection could come from the bursa itself, given its communication with the hip joint.7 On the right side, the infection could have spread through bone fissures present within the acetabulum, due to the screw penetrating within the pelvis. Another explanation to the bilateral infection would be the formation of a pseudocapsule around the hip, secondary to a primary arthroplasty of the hip. This pseudocapsule may have easily communicated with the adjacent bursa of the psoas, allowing the infection to spread to the ipsilateral hip joint.

In a retrospective study, Dauchy et al9 found a psoas abscess in 12% of patients admitted with prosthetic hip infection. In another study,10 7 of 214 patients assessed at CT for hip infection after hip arthroplasty also presented a psoas abscess.

A CT scan with soft tissue window is the standard for assessment of the location, size and extent of the abscess in 80–100% of patients,6 but MRI is more sensitive.2 To the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence in the literature of a case of bilateral abscess of the psoas muscle associated with bilateral hip infection after hip arthroplasty caused by S. anginosus. The incidence of periprosthetic deep infection is 0.3–1.7%. Its management is challenging,12 and remains controversial.13 The gold standard is two-stage revision surgery, with eradication of the infection in more that 90% of patients.14 Based on the algorithm of management by Zimmerli et al,15 we performed a two stage re-implantation bilaterally. In this instance, the use of the antibiotic-loaded cement spacer and specific systemic antibiotic therapy was decisive.

Learning points.

Simultaneous presentation of bilateral psoas abscess with prosthetic joint infection is extremely rare.

Streptococcus anginosus is an uncommon cause of joint infection and is usually isolated from the oral and gastrointestinal tract. Efforts should be made to rule out primary infection from these sites.

Two-stage revision is the gold standard treatment of prosthetic joint infection.

It is imperative to serially monitor infective markers in the interval period and perform an aspiration of the involved joint before reimplantation.

It is often a multidisciplinary approach that dictates a successful end result and functional outcome.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Andrea Volpin at @AndreaVolpin and Antonio Berizzi at @aberizzi

Contributors: AB was involved in the overall care of the patient. AV and SGK were involved in the preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bartolo DC, Ebbs SR, Cooper MJ. Psoas abscess in Bristol: a 10-year review. Int J Colorectal Dis 1987;2:72–6. 10.1007/BF01647695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields D, Robinson P, Crowley TP. Iliopsoas abscess—a review and update on the literature. Int J Surg 2012;10:466–9. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong OF, Ho PL, Lam SK. Retrospective review of clinical presentations, microbiology, and outcomes of patients with psoas abscess. Hong Kong Med J 2013;19:416–23. 10.12809/hkmj133793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ash N, Salai M, Aphter S, Olchovsky D. Primary psoas abscess due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus concurrent with septic arthritis of the hip joint. South Med J 1995;88:863 10.1097/00007611-199508000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Leung H, Kadow C et al. Septic arthritis of the hip complicating Salmonella psoas abscess: case report. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1992;26:305 10.3109/00365599209180889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dala-Ali BM, Lloyd MA, Janipireddy SB et al. A case report of a septic hip secondary to a psoas abscess. J Orthop Surg Res 2010;5:70 10.1186/1749-799X-5-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buttaro M, Gonzalez DV, Piccaluga F. Psoas abscess associated with infected total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2002;17:230–4. 10.1054/arth.2002.28734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plaza R, Soriano A, Tomás X et al. Psoas abscess associated with infected total hip arthroplasty: a case report. Hip international 2006;16:234–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauchy FA, Dupon M, Dutronc H et al. Association between psoas abscess and prothetic hip infection: a case control study. Acta Orthop 2009;80:198–200. 10.3109/17453670902947424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-Zabala I, García-Ramiro S, Bori G et al. Psoas abscess associated with hip arthroplasty infection. Rev Esp Quimioter 2013;26:198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giuliano S, Rubini G, Conte A et al. Streptococcus anginosus group disseminated infection: case report and review of literature. Infez Med. 2012;20:145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Arco A, Bertrand ML. The diagnosis of periprosthetic infection. Open Orthop J 2013;7:178–83. 10.2174/1874325001307010178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard HA, Liddle AD, Burke O et al. Single- or two-stage revision for infected total hip arthroplasty? A systematic review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:1036–42. 10.1007/s11999-013-3294-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherubino P, Puricelli M, D'Angelo F. Revision in cemented and cementless infected hip arthroplasty. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:190–6. 10.2174/1874325001307010190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645–54. 10.1056/NEJMra040181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]