Abstract

Objectives

(1) Summarise chest ultrasound accuracy to diagnose radiological consolidation, referenced to chest CT in patients with acute respiratory failure (ARF). (2) Directly compared ultrasound with chest X-ray.

Setting

Hospitalised patients.

Participants

Studies were eligible if adult participants in respiratory failure underwent chest ultrasound to diagnose consolidation referenced to CT. Exclusion: (1) not primary study, (2) not respiratory failure, (3) not chest ultrasound, (4) not consolidation, (5) translation unobtainable, (6) unable to extract data, (7) unable to obtain paper. 4 studies comprising 224 participants met inclusion.

Outcome measures

As planned, paired forest plots display 95% CIs of sensitivity and specificity for ultrasound and chest X-ray. Sensitivity and specificity from each study are plotted in receiver operator characteristics space. Meta-analysis was planned if studies were sufficiently homogeneous and numerous (≥4). Although this numerical requirement was met, meta-analysis was prevented by heterogeneous units of analysis between studies.

Results

All studies were in intensive care, with either a high risk of selection bias or high applicability concerns. Studies had unclear or high risk of bias related to use of ultrasound. Only 1 study clearly performed ultrasound within 24 h of respiratory failure diagnosis. Ultrasound sensitivity ranged from 0.91 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.97) to 1.00 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.00). Specificity ranged from 0.78 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.94) to 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00). In two studies, chest X-ray had lower sensitivity than ultrasound, but there were insufficient patients to compare specificity.

Conclusions

Four small studies suggest ultrasound is highly sensitive and specific for consolidation in ARF, but high risk of bias and concerns about applicability in all studies may have inflated diagnostic accuracy. Further robustly designed studies are needed to define the role of ultrasound in this setting.

Trial registration number

http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ (CRD42013006472).

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Comparison of sonographic consolidation with a reference of radiological consolidation.

Restricted to studies with reliable gold standard of chest CT.

Examination of the influence of units of analysis on diagnostic accuracy reporting.

Small number of eligible studies.

Meta-analysis prevented by heterogeneous units of analysis.

Introduction

Acute respiratory failure (ARF) is common and deadly. Published incidence rates1 2 suggest approximately 50 000 patients each year in the UK at the severest end of the ARF spectrum may require ventilatory support. A quarter of these have underlying pneumonia,2 and face mortality rates as high as 50%.3

Mortality escalates further when the cause of ARF is misdiagnosed, which occurs in one in five patients4 due, in part, to imaging limitations. Patients are difficult to position for chest X-ray5 resulting in suboptimal films which may miss consolidation,6 the commonest pattern of pneumonic infiltrate. Conversely, chest CT is highly sensitive but entails risks of transporting critically ill patients.7 Both shortcomings of traditional imaging may be overcome by chest ultrasound. Unlike X-ray, ultrasound does not require optimal patient positioning. Unlike CT, ultrasound can be brought to the bedside.

Narrative reviews,8 consensus guidelines9 and systematic reviews10 11 all advocate the use of ultrasound to diagnose pneumonia, but crucially, most studies of ultrasound accuracy have not examined patients in ARF settings. In those that do, the reference standard is often the final clinical diagnosis, risking incorporation bias if ultrasound itself forms part of that standard.

Further confusion arises when ultrasound accuracy studies use ‘pneumonia’ as the target condition. The commonest pneumonic infiltrate on imaging is the shadowing termed ‘consolidation’. (Less frequently, pneumonia may cause other imaging findings apart from consolidation, and consolidation may occasionally be caused by conditions other than pneumonia). While ultrasound can diagnose consolidation (an imaging finding), only clinicians diagnose pneumonia (a clinical diagnosis) by expertly blending imaging findings with available clinical information.12 However, such clinical incorporation bias distorts estimates of ultrasound accuracy. Instead, the most appropriate target condition for the imaging finding of sonographic consolidation is another imaging finding, in this case, radiographic consolidation on chest CT.

To address these key issues, we undertook a systematic review to summarise the accuracy of chest ultrasound to diagnose radiological consolidation, referenced to chest CT, in the specific setting of hospitalised patients with ARF. We also directly compared ultrasound with chest X-ray, the commonest screening test for consolidation in ARF. We excluded paediatric studies because children have a different range of aetiologies for ARF.13

Methods

The protocol was registered at (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) (review registration number CRD42013006472) and attached as a supplement; key points are summarised here. The review is reported according to PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses14).

Inclusion criteria

Studies: cohort, cohort with nested one-gate case-control studies (participants with and without consolidation), randomised controlled trials (ultrasound vs chest X-ray).

Timing: 24 h or less between ARF diagnosis and ultrasound scanning. If insufficient such studies were found, studies where ultrasound was performed more than 24 h after diagnosis of ARF would be included.

Participants: adults (aged 18 years or older) admitted to any hospital setting with ARF. Studies were excluded if patients were discharged home directly from the emergency department within 24 h without ward admission. ARF defined as: (1) arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) <60 mm of mercury, without supplemental oxygen, or (2) arterial oxygen saturation of <90% on pulse oximetry, without supplemental oxygen, or (3) supplemental oxygen required to prevent (1) or (2), or (4) author diagnosis of ARF.

Index: B-mode ultrasound examining lungs and pleura.

Comparator: studies comparing chest X-ray with chest ultrasound. Studies evaluating only chest X-ray excluded.

Target condition: radiological consolidation. Studies referencing chest ultrasound to a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia excluded.

Reference standard: chest CT, defined as helical CT to examine the thorax. Studies included if some patients received CT, but only when data could be analysed in the CT subgroup.

Exclusion criteria

The following hierarchy was employed: (1) not a primary study; (2) not respiratory failure; (3) not chest ultrasound; (4) not consolidation; (5) translation unobtainable; (6) unable to extract data to populate 2×2 contingency tables; (7) unable to obtain paper through both Bodleian (University of Oxford) and British Libraries.

Search

A healthcare librarian assisted with strategy development. Several iterations were trialled using two reference studies. The full search was run on 22 October 2013, in Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present, Ovid Embase 1974 to 2013 October 21, and Web of Knowledge Science Citation Index Expanded (see online supplementary appendix 1). An update search was run on 6 August 2014 prior to publication. Filters were not used and no language or date restrictions applied. Only published studies were included. Reference lists, citation searches, citing alerts in electronic journals, and the ‘related articles’ feature in PubMed were also used.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened according to inclusion and exclusion by two reviewers independently of each other, and results pooled. Full texts were assessed for inclusion independently by two reviewers. Differences were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, referral to a third reviewer.

Data collection

Prespecified data extraction forms (see online supplementary appendix 2) were developed,15 trialled in one study and modified. Data items included participants, index, comparator, reference, flow and diagnostic performance. Data were independently extracted by two reviewers. Differences were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, referral to a third reviewer.

Quality assessment

QUADAS2 (the Revised Tool for Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)16 was tailored for this review (see online supplementary appendix 3). Rating guidelines were developed, piloted in one included study, and applied to remaining studies by both reviewers independently. Differences were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, referral to a third reviewer.

Analysis plan

Most studies were expected to analyse patients, although we anticipated beforehand that studies might report results for each lung. We did not anticipate reporting by lung region. We considered analysis of any units other than patients as biased, since one lung (or lung region) of a patient is not independent of the other.

Paired forest plots were used to display 95% CIs of sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity and specificity from each study were plotted in receiver operator characteristics (ROC) space. Meta-analysis was planned if studies were sufficiently homogeneous and numerous (≥4). Although this numerical requirement was met, meta-analysis was prevented by heterogeneous units of analysis between studies. Details of the planned meta-analysis are available at the registered protocol. Where ultrasound was compared with chest X-ray, sensitivity and specificity for both tests were plotted in ROC space using Revman 5.17 Tests of unpaired proportions for large samples were used to compare tests within the same study, as sufficient data were unavailable for paired comparison.

Results

Study selection

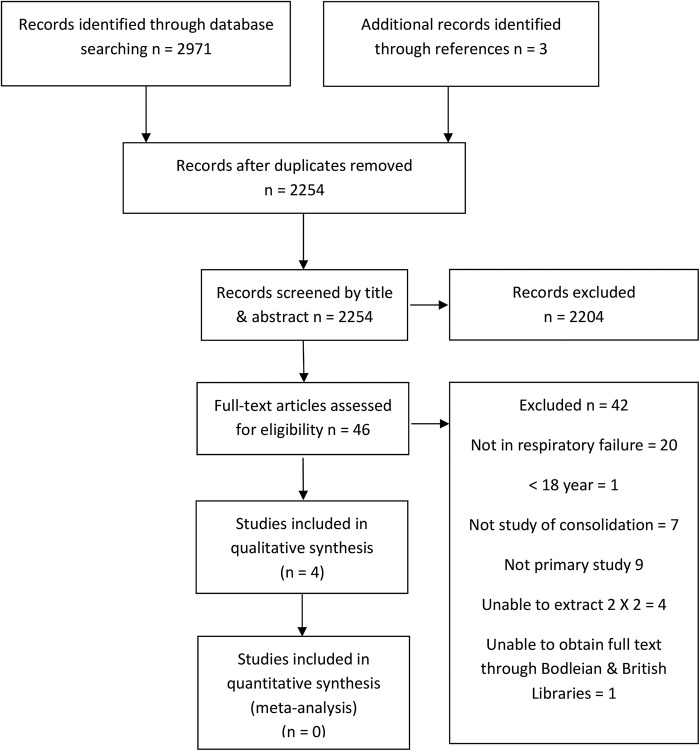

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart. Totals from both (original and update) searches are combined. Four studies met inclusion criteria.18–21 The 2×2 contingency tables could be extracted from all included studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study identification and selection.

We were concerned regarding possible duplication or overlap of cohorts, because two included papers had the same first author and year of publication.18 19 However, we found key differences between the studies which rendered this unlikely (table 1).

Table 1.

Differences in the two studies by Lichtenstein

| Lichtenstein et al 200418 | Lichtenstein et al 200419 | |

|---|---|---|

| Institution | Pitié-Salpétrière Hospital (stated in text) | Hopital Ambroise-Pare (implied by: author affiliation; acknowledgement of the ICU department head; acknowledgement of the Radiology department head where scans took place) |

| Type of ICU | Surgical | Medical |

| CT scanner used | Tomoscan SR 7000 (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) | CT Twin Flash (Elscint Limited, Haifa, Israel) |

| Reason for CT | Research study protocol | Clinical decision |

| Recruitment Period | Unstated, but inferred as 1993–1997 (from another paper arising from the same CT ARDS study, Puybasset et al, 2000) | Unstated. |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit.

Study characteristics

Table 2 summarises settings and patient characteristics of studies. All four studies were intensive care cohorts, but each reported different severity measures making comparison of ARF severity difficult.

Table 2.

Included studies: patient characteristics

| Author country | Study type/period | Demographics | Setting | Inclusion | Illness severity | Mechanical ventilation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lichtenstein et al 2004,18 France |

Cohort, likely 1993–1997 | n=32, Age 58+/-15 (SD), M:F Not stated | Surgical ICU | ARDS, (pneumonia 18, pulmonary contusion 4, aspiration pneumonia 4, fat embolism 1, septic shock 3, cardiopulmonary bypass 2) | Lung injury severity score 2.6±0.8 (SD), (ie, severe), ARDS severity score of 11±6 (SD), Mortality 42% | All |

| Lichtenstein et al 2004,19 France | Cohort, period not stated | n=60, Age 53 (range 20–84), M:F 37:23 | Medical ICU |

Patients with critical illness requiring chest CT | Not stated | 30/60 |

| Xirouchaki et al 2011,20 Greece | Cohort, period not stated | n=42, Age 57.1±21.5 (SD), M:F 34:8 | Mixed ICU | Patients with critical illness requiring chest CT (sepsis/multiorgan failure 18, trauma 11, Airways disease 7, pulmonary oedema 2, post-operative respiratory failure 2) | APACHE2 16.5±6.5 (SD) | All |

| Refaat, Abdurrahman 2013,21 Egypt |

Cohort, 2012–2013 | n=90, Age 50 (45–65), M:F 55:35 | Chest ICU | Respiratory failure (pneumonic consolidation 16, lung cancer 7, lung metastases 7, pleural effusion 36, pneumothorax 12, hydropneumothorax 6, mesothelioma 7) | Not stated | Not stated |

APACHE2, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; F, female; ICU, intensive care unit; M, male; n, number.

Table 3 summarises ultrasound methods and units of analyses. Only one study18 met our criterion for preferred studies, with ultrasound undertaken within 24 h of intensive care unit (ICU) admission (and thus probably of ARF diagnosis). In the other studies, timing of ultrasound in relation to ARF diagnosis was not stated. Scanning protocols were similar across all studies; each lung was divided into six regions; anterior, lateral and posterior; with upper and lower divisions. Three studies employed microconvex probes, the fourth used both linear and convex probes. Probe frequency ranged between 3.5 and 10 MHz.

Table 3.

Included studies: ultrasound technique, signs of consolidation and units of analysis

| Study | Ultrasound timing | Sonographer | Probe/scanner | Scan position | Scan protocol | Ultrasound signs of consolidation | Unit of analysis | Consolidation prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lichtenstein et al 200418 | Within 24 h of ICU admission (approximated to ARF diagnosis) | 1 intensivist (of 2), experience not quantified | Micro-convex 5 MHz, Portable (Hitachi 405) | Supine | 12 lung regions | Tissue-like pattern, no change in dimensions with respiration. Air bronchograms not mandatory | Lung region (12/patient) | 31% of lung regions |

| Lichtenstein et al 200419 | Unstated | 2 intensivists (κ coefficient 0.89) experience not quantified | Micro-convex 5 MHz, Portable (Hitachi 405) | Supine | 12 lung regions | Tissue-like pattern, arising from the pleural line, irregular deep border (regular if lobar), no change in dimensions with respiration. Air bronchograms not used | Lung (2/patient) | 56% of lungs |

| Xirouchaki et al 201120 | Unstated | 1 intensivist, 4 years’ experience | Micro-convex 5–9 MHz, Portable (Hitachi 8500) | Supine and lateral | 12 Lung regions | Tissue-like pattern±power Doppler. Irregular deep border not used | Lung (2/patient) and Lung region (12/ patient) | 24% of lungs, but 79% of lung regions |

| Refaat, Abdurrahman 201321 | Unstated | 1 radiologist, >7 years’ experience | Linear 7.5–10 MHz and convex 3.5 MHz, Portable Shenzhen mindray DP-1100 Plus) | Supine and lateral Erect when possible |

12 lung regions | Hypoechoic pattern, non-homogenous echo-texture, irregular shape, serrated margin, air and fluid bronchograms | Patient | 18% of patients |

Risk of bias and applicability concerns

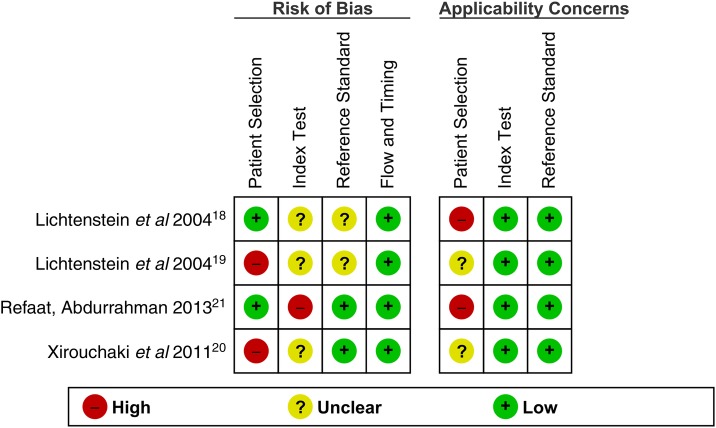

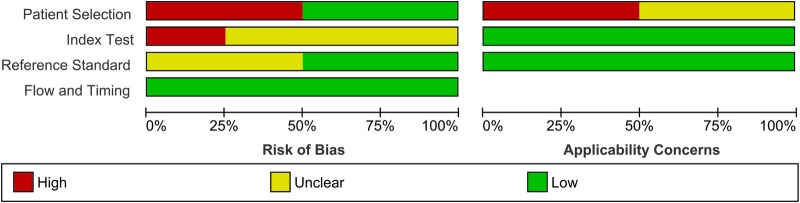

Figures 2 and 3 summarise the quality assessment of individual primary studies. Applicability was considered in relation to our review question which examined the diagnostic accuracy of chest ultrasound for CT-detected radiographic consolidation in adults with ARF.

Figure 2.

QUADAS2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies) risk of bias and applicability assessment of individual studies.

Figure 3.

QUADAS2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies) risk of bias and applicability assessment across primary studies.

Lichtenstein et al 2004.18

Selection: There was a low risk of selection bias due to consecutive recruitment of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.18 However, since acute respiratory distress syndrome represents the highest acuity of ARF, concerns regarding applicability were high.

Index Test: The risk of bias was unclear as it was not stated whether sonographers were blinded to clinical information, (although blinded to CT). Applicability concerns were low.

Reference Test: CT interpretation was blinded to ultrasound results, but clinical data may have been available, so risk of bias was unclear. Applicability concerns were low.

Flow and timing: CT was performed within 6 h after ultrasound. Risk of bias was low.

Lichtenstein et al 2004.19

Selection: The risk of selection bias was high because participants were recruited on the clinical need for CT.19 Most patients were likely in a state of ARF based on their need for intubation and specific diagnoses; however, ARF was not specifically stated, so applicability concerns were unclear.

Index Test: The risk of bias was unclear as it was not stated whether sonographers were blinded to clinical information, (although blinded to CT). Applicability concerns were low.

Reference Test: CT interpretation was blinded to ultrasound results, but clinical data may have been available, so risk of bias was unclear. Applicability concerns were low.

Flow and timing: CT was performed within 6 h after ultrasound. The risk of bias was low.

Xirouchaki et al, 2011.20

Selection: Risk of selection bias was high as participants were recruited on their clinical need for CT.20 Again, most patients were likely in a state of ARF based on their need for intubation and specific diagnoses; however, ARF was not specifically stated, so applicability concerns were unclear.

Index Test: Risk of bias was unclear as it was not stated whether sonographers were blinded to clinical information (although blinded to CT). Applicability concerns were low.

Reference Test: CT was interpreted blinded to both clinical information and ultrasound results, giving a low risk of bias. Applicability concerns were low.

Flow and timing. CT was performed no longer than 6 h after ultrasound. Risk of bias was low.

Refaat, Abdurrahman 2013.21

Selection: Recruitment was consecutive and exclusions were reasonable, giving a low risk of selection bias.21 The aetiological diagnoses in this patient group were restricted to a subgroup of respiratory failure aetiologies, causing high applicability concerns.

Index Test: The risk of bias was high, as the sonographer had access to clinical information. There were low applicability concerns.

Reference Test: CT was interpreted blind to ultrasound results, giving a low risk of bias. Applicability concerns were low.

Flow and timing: CT was performed within 24 h of ultrasound; risk of bias was low.

Analysis

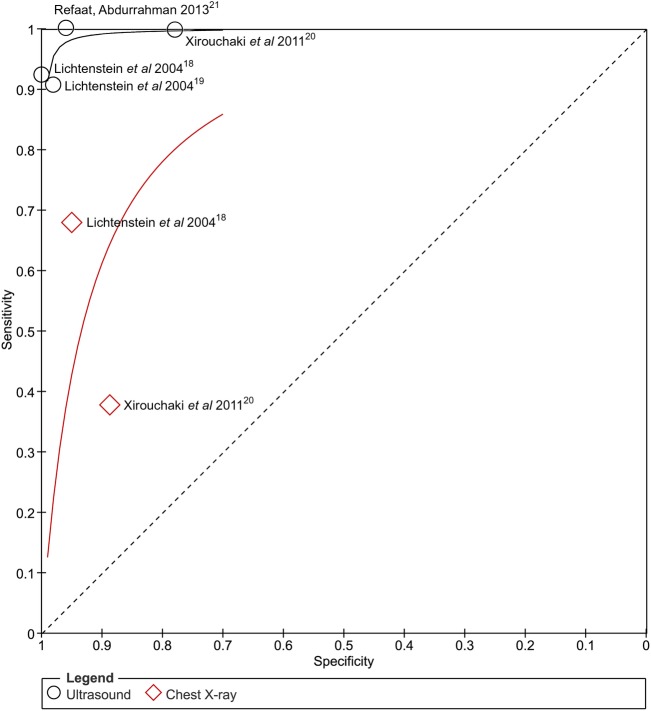

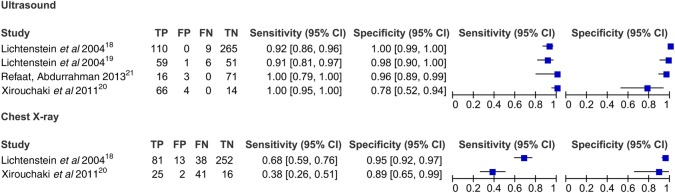

Ultrasound

Sensitivity for diagnosing CT-detected consolidation ranged from 0.91 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.97) to 1.00 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.00, figure 4). Specificity ranged from 0.78 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.94) to 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound and chest X-ray for included studies. Note different units of analyses which preclude pooling of studies: lung regions (12 per patient) in Lichtenstein et al 2004;18 lungs (2 per patient) in Lichtenstein et al 200419 and Xirouchaki et al 2011;20 and individual patients in Refaat, Abdurrahman 2013.21

Ultrasound compared against chest X-ray

Two studies, both of which only included ventilated patients18 20 (figures 4–6) evaluated both ultrasound and chest X-ray in the same patient populations, the best study design to compare tests.22 In both studies, the sensitivity of ultrasound was significantly greater than that of chest X-ray; 0.24 higher (95% CI 0.15 to 0.34, p<0.0001; figures 4 and 6) in the first study18 and 0.62 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.74, p<0.0001) in the second20 (figures 4 and 6). When compared using 12 lung regions per patient, specificity was higher for ultrasound (0.049, 95% CI 0.023 to 0.075, p=0.0003) in the first study,18 but lower in the second (−0.049, 95% CI −0.23 to −0.075, p=0.0003).20 Specificity compared at two lung regions per patient lacked sufficient power to detect a difference (figure 4).

Figure 5.

Sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound and chest X-ray for consolidation.

Figure 6.

Direct comparisons for ultrasound and chest X-ray in two individual studies. Units of analysis are lungs (2 per patient) for Xirouchaki et al 2011,20 and lung regions for Lichtenstein et al 200418 (12 per patient).

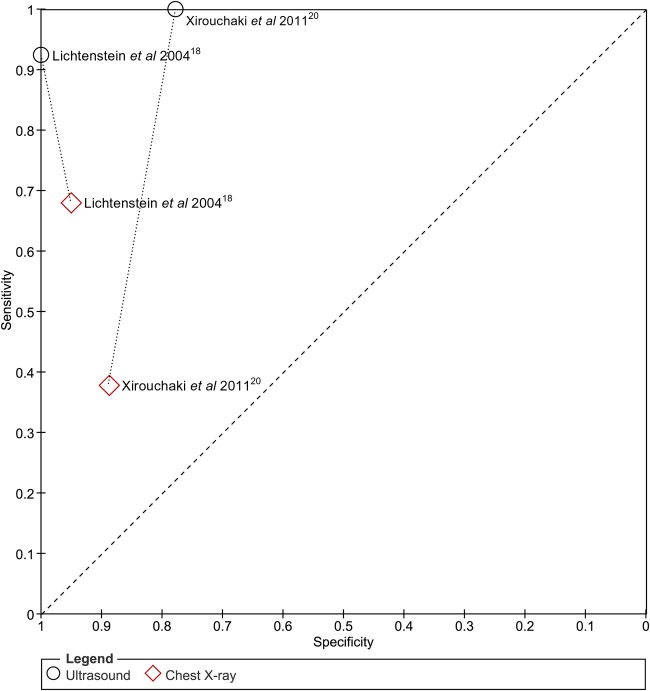

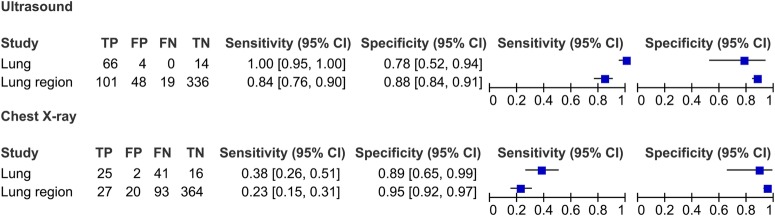

Impact of unit of analysis

Three different units of analyses were reported across four studies (table 3). Only one study used the patient as a unit of analysis.21 A second study19 used only the lung (two per patient), and a third18 used only lung regions (12 per patient).

The fourth study20 reported its results using the lung as the unit of analysis, but provided additional data using lung regions in an electronic supplement. This provided the opportunity to study the impact of different units of analysis on test characteristics within the same data set (figure 7).

Figure 7.

Impact of units of analyses on sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound and chest X-ray for consolidation. Data from Xirouchaki et al 201120 are stratified according to two units of analysis; ‘lung’ (2/patient) and ‘lung region’ (12/patient). In comparison to lung analysis, lung region analysis reduces sensitivity but inflates specificity. It also increases total study numbers, giving the appearance of tighter estimates of precision.

Importantly, for both ultrasound and chest X-ray, changing the unit of analysis from lung to lung region reduced sensitivity but enhanced specificity, and gave more precise estimates of accuracy (narrower CIs). It also inflated the prevalence of consolidation.

Reported sources of ultrasound and chest X-ray error

In one study,19 five of six false negative ultrasounds were in patients with posteriorly placed consolidation. This study evaluated patients only in the supine position, which may hinder the detection of posterior consolidation.

In another study,20 all four false positive ultrasounds detected only small areas of consolidation. This study only used a tissue-like pattern to diagnose consolidation which may have reduced specificity.

None of the studies proposed reasons for false positive or false negative chest X-ray results in their discussion.

Synthesis of results

Meta-analysis was not performed due to heterogeneous units of analysis across studies.

Additional analyses

Heterogeneity could not be explored due to the small number of studies, apart from comparisons between different units of analysis.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

In four small studies, the reported sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for CT-diagnosed consolidation was high among hospitalised patients with ARF. Ultrasound sensitivity was greater than for chest X-ray in two studies, directly comparing both methods in the same patient populations. However, paired comparisons in individual patients which are the best evidence for comparing tests were not available.

This review identified four quality issues that impact the reported test accuracy of ultrasound in included studies. First, patient selection in every eligible study was either at high risk of bias, or had concerns about applicability to our systematic review. These concerns included recruitment of participants in ICU at the severest acuity of ARF (spectrum bias), restriction to limited ARF aetiologies, and non-consecutive recruitment. The sensitivity of ultrasound for consolidation may thus be markedly poorer in unselected populations with less severe ARF (and lower burdens of consolidation), or a wider range of ARF aetiologies.

Second, in no study were sonographers clearly blinded to clinical data. This is pertinent because sonographers (who in three studies were actually clinicians) could have integrated bedside clinical data with ultrasound evaluation, artificially inflating ultrasound sensitivity.

Third, only one study specified that ultrasound was performed within 24 h of ICU admission (and presumably, of ARF diagnosis). The more time elapses before ultrasound is performed, the more likely lung consolidation would progress to a detectable extent, but the less likely the test result would improve patient outcome. This would boost reported ultrasound sensitivity, but overstate its utility as an initial test.

Fourth, the two studies comparing ultrasound with chest X-ray were undertaken wholly among ventilated patients. This spectrum bias would augment ultrasound sensitivity since patients would be more likely to have extensive (and more easily detectable) consolidation. The necessarily supine chest X-rays would render films less sensitive for consolidation, again exaggerating the benefit of ultrasound.

The variable units of analyses employed across studies also introduce additional concerns. Different units of analyses had an evident effect on test accuracy. The use of lung regions for analysis (as opposed to lungs) diminished sensitivity, inflated specificity, and gave the misleading appearance of greater precision. Another drawback of different units of analyses across studies is that meta-analysis of results would be misleading because studies using lung regions would have undue numerical weight. For these reasons, we highly recommend future studies be conducted and reported always including patients as the unit of analysis. This is the most appropriate and relevant unit, particularly since individual patients are usually the unit of clinical management.

Additionally, we strongly recommend that future studies should compare different tests in the same patients and present results as 2×2 tables of paired results separately in disease-positive and disease-negative patients. This is important to understand whether false-positive and false-negative results occur in the same or different patients, and to design subsequent studies.

Compared with previous systematic reviews,10 11 the distinguishing features of our review were: (1) the emphasis on a single clinical presentation, that is, ARF; in this ‘high stakes’ patient group, the additional resources required to perform ultrasound are better justified than in less severe clinical presentations; (2) the requirement for a CT reference; providing greater confidence in estimates of diagnostic accuracy; (3) the focus on a single radiographic abnormality, that is, consolidation rather than the clinical diagnosis of pneumonia, removing the risk of bias of incorporating clinical information into the target condition, and (4) the preregistered systematic review protocol.

Limitations

This review is limited by the small number of studies meeting inclusion as of August 2014. Four studies were performed by three investigator groups, limiting generalisability to other clinical environments. Where more than one ultrasound sign was used to diagnose consolidation, test characteristics of individual signs for consolidation were not assessed. The small number of studies and different units of analyses prevented meta-analysis, exploration of clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and pooled comparisons between ultrasound and chest X-ray.

Conclusion

Based on a small body of evidence at high risk of selection bias and index test bias, ultrasound is both sensitive and specific for CT-detected consolidation in ARF. Heterogeneous units of analyses between studies limited comparisons between studies.

While ultrasound may have a role as an add-on test in ARF when the chest X-ray is negative for consolidation, this possibility is tempered by the narrow evidence base available associated with substantial risks of bias and applicability concerns. We conclude there is insufficient evidence to support the widespread introduction of ultrasound to detect consolidation in hospitalised patients diagnosed with ARF.

Robustly designed studies are needed, controlling for the fundamental biases discussed above. They should aim to determine if an add-on, or replacement test strategy is truly beneficial, and identify clinical determinants of test accuracy. Ultrasound should be compared with current methods and also to emerging diagnostic alternatives using biomarkers23 and other novel imaging.24 The feasibility of implementing ultrasound should also be studied, coupled with clinical and cost-effectiveness modelling.

Footnotes

Contributors: MH is responsible for the original idea, first draft of protocol, first reviewer, first draft of manuscript. SM supervised the protocol development and overall review. JPC is the second reviewer. NMR is the third reviewer. EKH conducted the search design and execution. All the authors analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The corresponding author may be contacted for clarification of data used in this systematic review.

References

- 1.Lewandowski K, Metz J, Deutschmann C et al. Incidence, severity, and mortality of acute respiratory failure in Berlin, Germany. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:1121–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luhr OR, Antonsen K, Karlsson M et al. Incidence and mortality after acute respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome in Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland. The ARF Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1849–61. 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9808136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodhead M, Welch CA, Harrison DA et al. Community-acquired pneumonia on the intensive care unit: secondary analysis of 17,869 cases in the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care 2006;10(Suppl 2):S1 10.1186/cc4927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray P, Birolleau S, Lefort Y et al. Acute respiratory failure in the elderly: etiology, emergency diagnosis and prognosis. Crit Care 2006;10:R82 10.1186/cc4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ovenfors C, Hedgecock MW. Intensive care unit radiology: problems of interpretation. Radiol Clin North Am 1978;16:407–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan AN, Al-Jahdali H, Al-Ghanem S et al. Reading chest radiographs in the critically ill (Part I): Normal chest radiographic appearance, instrumentation and complications from instrumentation. Ann Thorac Med 2009;4:75–87. 10.4103/1817-1737.49416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouhemad B, Zhang M, Lu Q et al. Clinical review: bedside lung ultrasound in critical care practice. Crit Care 2007;11:205 Review 10.1186/cc5668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hew M, Heinze S. Chest ultrasound in practice: a review of utility in the clinical setting. Intern Med J 2012;42:856–65. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02816.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M et al. , International Liaison Committee on Lung Ultrasound (ILC-LUS) for International Consensus Conference on Lung Ultrasound (ICC-LUS). International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:577–91. 10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu QJ, Shen YC, Jia LQ et al. Diagnostic performance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of pneumonia: a bivariate meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014;7:115–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chavez MA, Shams N, Ellington LE et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 2014;15:50 10.1186/1465-9921-15-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC et al. British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax 2009;64(Suppl 3):iii1–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider J, Sweberg T. Acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Clin 2013;29:167–83. 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE et al. Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:51–5. Review 10.2214/ajr.181.1.1810051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME et al. , QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:529–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macaskill P, Gatsonis C, Deeks JJ et al. Chapter 10: analysing and presenting results. In: Deeks JJ, Bossuyt PM, Gatsonis C, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy Version 1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2010. http://srdta.cochrane.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichtenstein D, Goldstein I, Mourgeon E et al. Comparative diagnostic performances of auscultation, chest radiography, and lung ultrasonography in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology 2004;100:9–15. 10.1097/00000542-200401000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtenstein DA, Lascols N, Mezière G et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of alveolar consolidation in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:276–81. 10.1007/s00134-003-2075-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xirouchaki N, Magkanas E, Vaporidi K et al. Lung ultrasound in critically ill patients: comparison with bedside chest radiography. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:1488–93. 10.1007/s00134-011-2317-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Refaat R, Abdurrahman L. The diagnostic performance of chest ultrasonography in the up-to-date work-up of the critical care setting. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 2013;44:779–89. 10.1016/j.ejrnm.2013.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takwoingi Y, Leeflang MM, Deeks JJ. Empirical evidence of the importance of comparative studies of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:544–54. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozinovski S, Hutchinson A, Thompson M et al. Serum amyloid a is a biomarker of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:269–78. 10.1164/rccm.200705-678OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masaryk T, Kolonick R, Painter T et al. The economic and clinical benefits of portable head/neck CT imaging in the intensive care unit. Radiol Manage 2008;30:50–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]