Abstract

Objectives

The insights that people with cystic fibrosis have concerning their health are important given that aspects of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) are independent predictors of survival and a decrease in lung function is associated with a decrease in HRQoL over time. Cross-sectional data suggest that key variables, other than lung function, are also associated with HRQoL—although study results are equivocal. This work evaluates the relationship between these key demographic and clinical variables and HRQoL longitudinally.

Design

Longitudinal observational study. Observations were obtained at seven time points: approximately every 2 years over a 12-year period.

Setting

Large adult cystic fibrosis centre in the UK.

Participants

234 participants aged 14–48 years at recruitment.

Outcome measure

Nine domains of HRQoL (Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Questionnaire) in relation to demographic (age, gender) and clinical measures (forced expiratory volume in 1 s, (FEV1)% predicted, body mass index (BMI), cystic fibrosis-related diabetes, Burkholderia cepacia complex, totally implantable vascular access device, nutritional and transplant status).

Results

A total of 770 patient assessments were obtained for 234 patients. The results of random coefficients modelling indicated that demographic and clinical variables were identified as being significant for HRQoL over time. In addition to lung function, transplant status, age, having a totally implantable vascular access device, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes, BMI and B. cepacia complex impacted on many HRQoL domains longitudinally. Gender was important for the domain of body image.

Conclusions

Demographic and changes in clinical variables were independently associated with a change in HRQoL over time. Compared with these longitudinal data, cross-sectional data are inadequate when evaluating the relationships between HRQoL domains and key demographic and clinical variables, as they fail to recognise the full impact of the CF disease trajectory and its treatments on quality of life.

Keywords: THORACIC MEDICINE, PSYCHIATRY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This work provides the first longitudinal data that evaluate the association between changes in clinical variables and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in cystic fibrosis.

Participants were followed–up every 2 years over a 12-year period.

These longitudinal data highlight the inadequacy of cross-sectional data which fail to recognise the full impact of the CF disease trajectory and its treatments on HRQoL.

This was a single-centre study.

Clinical variables that were not evaluated included the frequency of pulmonary exacerbations and microbiological status.

Introduction

Over the past three decades advances in the care of people with cystic fibrosis (CF) have led to the median age of survival increasing steadily, so that in 2014, median survival had reached 36.6 years in the UK.1 Greater longevity is at a cost of life-long adherence to a complex and burdensome daily regimen of up to 4 h/day,2 3 which includes chest physiotherapy, daily enzyme replacement therapy, high-fat requirements, exercise and oral, inhaled and intravenous medication. With increasing age, patients may develop complications including CF-related diabetes, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, atypical mycobacteria, osteoporosis and arthropathy. Despite the burdens that the disease and its treatments impose on them, people with CF are psychologically well-adjusted and generally report a good health-related quality of life (HRQoL) on many domains of generic and CF specific measures.4–9 Understanding the determinants for sustaining a good HRQoL with advancing CF disease may assist in the development of interventions to improve it.

Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that demographic and clinical variables appear to impact on life quality; with age,4–5 gender,5–7 lung transplant status and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)7–9 most consistently associated with HRQoL. However, while important associations were identified, much of the variation in HRQoL remained unexplained4 8 10 11 and causal relationships could not be ascertained. Although authors acknowledge that longitudinal work is required to understand these relationships, this is rarely undertaken and assumptions are simply extrapolated from cross-sectional data. Over 1 or 2 years there is little change in HRQoL at the population level.12–14 Recently, two studies have linked HRQoL reporting over many years with clinical outcomes in CF. Patient-reported physical function has been shown to be an independent predictor of survival in CF15 and recent longitudinal work has demonstrated that, over a decade, FEV1% predicted and HRQoL domains declined slowly, with a decrease in lung function being associated with a decrease in HRQoL domains.16

In addition to lung function, cross-sectional data suggest that other key demographic and clinical variables are associated with HRQoL. This work aims to evaluate the relationship between these variables and HRQoL longitudinally.

Methods

Participants and procedure

All patients who attended a large Adult Cystic Fibrosis Centre in the UK were approached to take part in the study. The Centre followed standard treatment protocols and annual reviews were undertaken as close to the patient's birthday as possible, predominantly when they were clinically stable. The CFQoL17 was mailed out every 2 years for completion prior to their clinic visit at which demographic and clinical variables were recorded. People with CF were followed–up, at approximately two yearly intervals, for 12 years. There were seven assessments (time points T1–T7 from 1998 to 2010). At each time point patients provided consent for their participation in accordance with ethical committee approval.

Measures

At each time point demographic, clinical and HRQoL variables were collected. Age, gender, FEV1% predicted, body mass index (BMI) and whether the person had cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD), Burkholderia cepacia complex or a totally implantable vascular access device (TIVAD) were recorded. Nutritional status (no oral calorie supplements, prescribed oral calorie supplements or prescribed enteral tube feeds) and lung transplantation (listed or received transplant) were also documented.

Quality of Life was measured using the Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (CFQoL).17 The CFQoL was developed and validated in the UK and was therefore the most appropriate CF-specific HRQoL measure for this UK sample. The instrument measures nine domains of functioning: Physical functioning, Social functioning, Emotional responses, Treatment issues, Chest symptoms, Body image, Interpersonal relationships, Career concerns and Concerns for the future. The psychometric properties of the instrument are good. Internal reliability of the domains was demonstrated using Cronbach's α coefficients (range 0.72–0.92, median 0.89) and item to total domain score correlations. Concurrent validity with three appropriate SF-36 domains (range r=0.64–0.74), known groups validity between different levels of disease severity, sensitivity across transient changes in health (effect size range, d=0.56–1.95) and test-retest reliability (r=0.74–0.96, median 0.91) were found to be robust. Each domain has a minimum score of 0% and a maximum score of 100%, with higher scores reflecting a better quality of life.

Statistical analyses

The modelling was carried out using all patients who entered the study. Not all patients entered the study at time point one (T1), but joined the study at later time points (T2–T7). Some patients died or dropped out during the 12 years, but their available data were still included in the analyses. Hence, the analyses were not based only on survivors.

Patient characteristics at all the times combined were described by summary statistics. The longitudinal relationships between the nine domains of CFQoL and the 11 variables recording patient characteristics were modelled using regression models with fixed and random coefficients. Random coefficients allowed the observations on an individual patient to be predicted by an individual random coefficient which was assumed to be sampled from a population of normally distributed coefficients across individuals. This type of modelling has been used frequently for longitudinal studies.18 19 For each CFQoL domain; CFQoL=100×S/N where S was the domain score and N was the maximum domain score. Maximum scores for the domains were: Physical functioning (50), Social functioning (20), Emotional responses (40), Treatment issues (15), Chest symptoms (20), Body image (15), Interpersonal relationships (50), Career concerns (20) and Concerns for the future (30). Statistical analysis of HRQoL is challenging because of the ‘ceiling effects’ for all HRQoL scales which have a maximum of 100%20 and because domain scores (S) are discrete measures that only have values which correspond to whole numbers; for example with Social functioning N is 20 and so Social functioning can take only the values 100%, 95%, 90% etc.

Therefore, binomial regression with fixed and random coefficients was chosen as a suitable modelling framework because the binomial is a discrete distribution for a score (S) that has a prescribed maximum (N). Binomial regression predicts within the range 0–100% because the model predicts the logit transformation of HRQoL (CFQoL on the logit scale), analogous to logistic regression. Models were fitted using the software MLwiN.21

The models estimated the means, variances and covariances of the random coefficients for the quantitative covariates FEV1% predicted, BMI and the model intercept. The categorical predictors of gender, CFRD, nutritional status (oral supplements and tube feeding), TIVAD, B. cepacia complex and transplant status (listed for or received transplant) were included as fixed effects. Age, although quantitative, was included as a fixed effect because age changes deterministically with time. The random coefficients were tested statistically to determine whether each should be retained as a random coefficient or could be included as fixed. For each CFQoL domain the maximal model was fitted which included all 11 patient variables and a variable was judged as having a significant association with a CFQoL domain if the p value for the variable in the maximal model was less than 0.1 (10% significance). This significance level was chosen because it is conventionally used for retaining terms in a multiple regression analysis with many variables. For the random coefficients the p value for the coefficient mean was used and for the fixed effects the p value of the fixed coefficient was used to determine significance. For each variable in the maximal model, the coefficients were used to calculate the typical change in HRQoL (%) from an initial value of HRQoL. The initial HRQoL (%) was transformed to the logit scale, the coefficient was applied and then the result was transformed back to the HRQoL scale. Initial HRQoL in the range 20–80% was used and the greatest and smallest changes in HRQoL were recorded.

Results

The intention was to follow individuals every 2 years but, on occasion, some patients failed to attend annual review or to participate in the study, or had died. Therefore, table 1 presents the number of patients who participated for each total number of study time points (T1–T7) and the consequent number of patient assessments which the clinic visits contributed to the longitudinal data. A total of 770 completed patient assessments were obtained for 234 patients. The median number of completed patient assessments was three with IQR 2–5 assessments.

Table 1.

Numbers of patients and patient assessments

| Number of time-points per patient | Patients (n) | Patient assessments (n) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 | 54 |

| 2 | 51 | 102 |

| 3 | 31 | 93 |

| 4 | 32 | 128 |

| 5 | 25 | 125 |

| 6 | 19 | 114 |

| 7 | 22 | 154 |

| Total | 234 | 770 |

The demographic, clinical characteristics and HRQoL measures recorded at all the assessments combined are shown in table 2. For the categorical variables, the percentage of assessments at which the patients had CFRD, oral supplements etc are provided. For the quantitative variables such as age, the mean, SD and range are shown.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patient assessments

| N (%) | Range | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patient assessments | 770 (100.0) | ||

| Female patient | 445 (57.8) | ||

| Oral supplements taken | 254 (33.0) | ||

| Enteral tube feeds taken | 122 (15.8) | ||

| CFRD present | 287 (37.3) | ||

| TIVAD fitted | 402 (52.2) | ||

| Burkholderia cepacia complex present | 58 (7.5) | ||

| Listed for transplant | 35 (4.5) | ||

| Received transplant | 97 (12.6) | ||

| Ages (years) | 14–57 | 28.5 ( 8.2) | |

| FEV1% predicted | 12–133 | 58.3 (23.8) | |

| BMI | 15–34 | 21.8 ( 3.1) | |

| Physical functioning | 2–100 | 83.0 (20.5) | |

| Social functioning | 0–100 | 84.7 (21.5) | |

| Emotional responses | 8–100 | 78.6 (20.6) | |

| Treatment issues | 0–100 | 74.7 (22.5) | |

| Chest symptoms | 0–100 | 76.6 (23.2) | |

| Body image | 0–100 | 69.8 (24.7) | |

| Interpersonal relationships | 2–100 | 64.5 (22.4) | |

| Career concerns | 0–100 | 61.7 (29.4) | |

| Concerns for the future | 0–100 | 45.0 (25.1) |

BMI, body mass index; CFRD, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, TIVAD, totally implantable vascular access device.

Longitudinal relationships between HRQoL and demographic and clinical variables

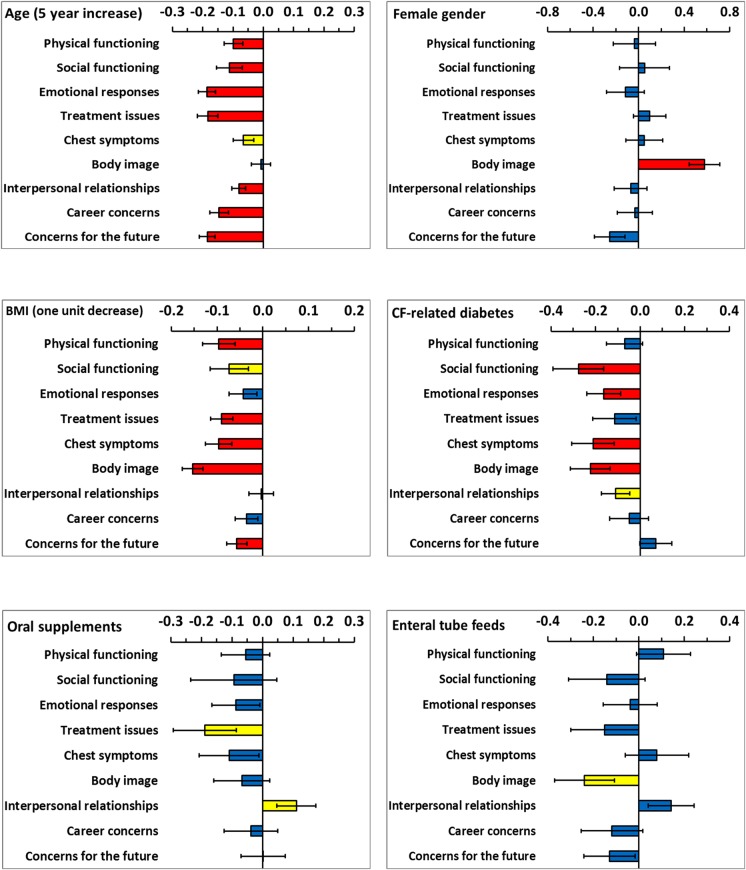

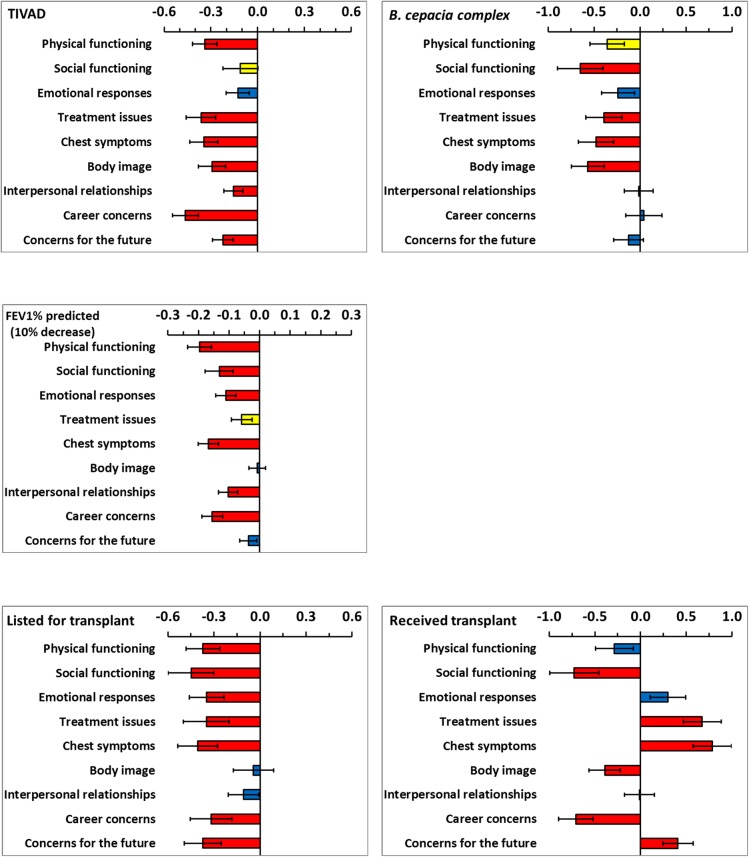

Each model for a domain of HRQoL included all demographic and clinical variables and the model coefficients are shown by variable in figures 1 and 2. Demographic and clinical variables which were significant at the 10% level were extracted and are presented in table 3 by HRQoL domain. The coefficients for age and FEV1% predicted were scaled (5 years increase and 10% decrease, respectively) to provide clinically meaning change since HRQoL changes slowly for these variables. In cross-sectional work, predominantly FEV1% predicted and transplant status were significantly associated with HRQoL.7–9 Longitudinally, in addition to lung function and transplant status, age, having a TIVAD, CFRD, BMI and B. cepacia complex were important for more than half of the HRQoL domains.

Figure 1.

Coefficients from the multilevel models for six demographic and clinical variables. The limits show plus and minus one SE. Coefficients are not significant (blue bars), significant at the 10% level (yellow bars) and significant at the 5% level (red bars).

Figure 2.

Coefficients from the multilevel models for five demographic and clinical variables. The limits show plus and minus one SE. Coefficients are not significant (blue bars), significant at the 10% level (yellow bars) and significant at the 5% level (red bars).

Table 3.

Variables significant at the 10% level in the multiple regression models together with adjusted coefficients, SEs and significance levels

| Domain | Coefficient (SE) | p Value | Domain | Coefficient (SE) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | Social functioning | ||||

| Age (5 years increase) | −0.10 (0.03) | <0.001 | Age (5 years increase) | −0.11 (0.04) | 0.008 |

| BMI (1 unit decrease) | −0.10 (0.04) | 0.007 | CFRD | −0.28 (0.11) | 0.015 |

| TIVAD | −0.34 (0.08) | <0.001 | BMI (1 unit decrease) | −0.07 (0.04) | 0.078 |

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | −0.36 (0.18) | 0.053 | B. cepacia complex | −0.65 (0.25) | 0.008 |

| FEV1% (10% decrease) | −0.20 (0.04) | <0.001 | FEV1% (10% decrease) | −0.13 (0.05) | 0.004 |

| Listed for transplant | −0.37 (0.11) | <0.001 | Listed for transplant | −0.45 (0.15) | 0.004 |

| Received transplant | −0.73 (0.27) | 0.007 | |||

| Emotional responses | Treatment issues | ||||

| Age (5 years increase) | −0.19 (0.03) | <0.001 | Age (5 years increase) | −0.18 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| CFRD | −0.16 (0.08) | 0.032 | BMI (1 unit decrease) | −0.09 (0.02) | <0.001 |

| TIVAD | −0.13 (0.07) | 0.087 | Oral supplements | −0.19 (0.10) | 0.068 |

| FEV1% (10% decrease) | −0.11 (0.03) | <0.001 | TIVAD | −0.36 (0.09) | <0.001 |

| Listed for transplant | −0.35 (0.11) | 0.002 | B. cepacia complex | −0.39 (0.20) | 0.045 |

| FEV1% (10% decrease) | −0.06 (0.03) | 0.078 | |||

| Listed for transplant | −0.35 (0.15) | 0.019 | |||

| Received transplant | 0.67 (0.21) | 0.001 | |||

| Chest symptoms | Body image | ||||

| Age (5 years increase) | −0.07 (0.03) | 0.054 | Female | 0.58 (0.13) | <0.001 |

| CFRD | −0.21 (0.10) | 0.027 | CFRD | −0.22 (0.09) | 0.013 |

| BMI (1 unit decrease) | −0.10 (0.03) | 0.001 | BMI (1 unit decrease) | −0.15 (0.02) | <0.001 |

| TIVAD | −0.35 (0.09) | <0.001 | Enteral tube feeds | −0.24 (0.13) | 0.069 |

| B. cepacia complex | −0.48 (0.19) | 0.013 | TIVAD | −0.30 (0.09) | 0.001 |

| FEV1% (10% decrease) | 0.17 (0.03) | <0.001 | B. cepacia complex | −0.57 (0.18) | 0.002 |

| Listed for transplant | −0.41 (0.13) | 0.002 | Received transplant | −0.39 (0.17) | 0.022 |

| Received transplant | 0.79 (0.21) | <0.001 | |||

| Interpersonal relationships | Career concerns | ||||

| Age (5 years increase) | −0.08 (0.02) | <0.001 | Age (5 years increase) | −0.15 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| CFRD | −0.11 (0.06) | 0.081 | TIVAD | −0.46 (0.08) | <0.001 |

| Oral supplements | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.081 | FEV1% (10% decrease) | −0.16 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| TIVAD | −0.16 (0.06) | 0.011 | Listed for transplant | −0.31 (0.14) | 0.019 |

| FEV1% (10% decrease) | −0.10 (0.03) | 0.001 | Received transplant | −0.71 (0.19) | <0.001 |

| Concerns for the future | |||||

| Age (5 years increase) | −0.19 (0.03) | <0.001 | |||

| Female | −0.26 (0.13) | 0.057 | |||

| BMI (1 unit decrease) | −0.06 (0.02) | 0.010 | |||

| TIVAD | −0.22 (0.07) | 0.001 | |||

| Listed for transplant | −0.37 (0.12) | 0.002 | |||

| Received transplant | 0.41 (0.17) | 0.015 | |||

BMI, body mass index; CFRD, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, TIVAD, totally implantable vascular access device.

The coefficients presented in table 3 and figures 1 and 2 apply to the logit scale (as described in the method section). This has the consequence that the actual change in HRQoL depends on the initial reported value of HRQoL before the change. To aid interpretation, table 4 shows the typical change in HRQoL domains for initial values in the range of 20–80%. For age (5 year increase), BMI (1 unit decrease), FEV1% predicted (10% decrease), oral supplements and enteral tube feeds, small changes, generally less than 5% were predicted. Having CFRD, TIVAD, B. cepacia complex and being listed for lung transplant predicted greater decrements across HRQoL domains. The largest changes in HRQoL were associated with having received a lung transplant; large increases in HRQoL occurred for Treatment issues, Chest symptoms, Concerns for the future and Emotional responses. Conversely, receiving a transplant predicted large decreases in Social functioning, Career concerns and Body image.

Table 4.

Predicted typical change in domain specific HRQoL (%) from an initial HRQoL in the range 20–80%

| Domain | Age 5 years increase |

BMI 1 unit decrease |

FEV1% 10% decrease |

CFRD | TIVAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 1.5–2.5 | 1.5–2.4 | 3.0–4.9 | 1.1–1.7 | 4.9–8.4 |

| Social functioning | 1.7–2.8 | 1.2–1.8 | 2.0–3.3 | 2.2–6.9 | 1.7–2.8 |

| Emotional responses | 2.8–4.6 | 0.7–1.1 | 1.7–2.7 | 2.5–4.1 | 2.0–3.2 |

| Treatment issues | 2.8–4.6 | 1.4–2.2 | 0.9–1.9 | 1.8–2.9 | 5.2–9.0 |

| Chest symptoms | 1.0–1.6 | 1.5–2.4 | 2.6–4.2 | 3.2–5.3 | 5.0–8.5 |

| Body image | 0.1–0.2 | 2.3–3.8 | 0.1–0.2 | 3.3–5.6 | 4.3–7.3 |

| Interpersonal relationships | 1.3–2.0 | 0.1–0.1 | 1.6–2.6 | 1.7–2.8 | 2.4–3.9 |

| Career concerns | 2.2–3.6 | 0.6–0.9 | 2.4–3.9 | 0.8–1.2 | 6.4–11.5 |

| Concerns for the future | 2.8–4.6 | 0.9–1.4 | 0.6–0.9 | 1.2–1.8* | 3.3–5.5 |

| Oral supplements | Enteral tube feeds | Burkholderia cepacia complex | Listed for transplant | Received transplant | |

| Physical functioning | 0.9–1.4 | 1.8–2.7* | 5.1–8.8 | 5.3–9.2 | 4.2–7.1 |

| Social functioning | 1.5–2.3 | 2.2–3.5 | 8.5–16.1† | 6.2–11.1 | 9.2–18.0 |

| Emotional responses | 1.4–2.2 | 0.6–1.0 | 3.6–6.0 | 5.0–8.6 | 5.2–7.4* |

| Treatment issues | 2.8–4.7 | 2.3–3.7 | 5.6–9.7 | 5.0–8.7 | 12.9–16.6* |

| Chest symptoms | 1.7–2.7 | 1.3–2.0* | 6.6–11.8 | 5.7–10.0 | 15.4–19.4* |

| Body image | 1.1–1.7 | 3.6–6.0 | 7.6–14.0 | 0.7–1.1 | 5.5–9.7 |

| Interpersonal relationships | 1.8–2.8* | 2.4–3.5* | 0.2–0.3 | 1.7–2.7 | 0.2–0.3 |

| Career concerns | 0.6–0.9 | 1.8–3.0 | 0.7–1.0* | 4.6–7.9 | 9.0–17.5 |

| Concerns for the future | 0.0–0.1* | 2.0–3.2 | 1.9–3.2 | 5.3–9.2 | 7.3–10.1* |

The change is a decrease unless otherwise indicated by *.

†Interpretation of table values: With colonisation with B. cepacia complex, Social functioning% is expected to decline by between 8.5 and 16.1 points depending on the Social functioning% domain score before colonisation.

BMI, body mass index; CFRD, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, TIVAD, totally implantable vascular access device.

Discussion

This is a longitudinal observational study and, as such, it has the advantage over a cross-sectional study of being able to determine temporality. For this reason, it is justifiable to interpret demographic and clinical changes as having impact on HRQoL. Hence, this work has demonstrated that the demands created by the CF disease trajectory and its treatments profoundly impact all aspects of a person's quality of life. Demographic and clinical measures in CF are highly inter-related and the need to separate out the individual effects of these measures on patient HRQoL presents a considerable challenge. The modelling approach taken has responded well to this challenge and has provided fundamental insight into the way in which changes in these measures impact on HRQoL.

In contrast to previous cross-sectional work, a greater number of demographic and clinical variables were identified as impacting HRQoL over time. This longitudinal work confirms the cross-sectional findings that advancing age, lung function and transplantation are important predictors of outcome across many domains of life quality. Variables which did not consistently emerge as important in cross-sectional regression models have also now been shown to be independent predictors of HRQoL longitudinally. These include BMI, having a TIVAD, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and B. cepacia complex.

We have recently reported data that assessed the natural progression of HRQoL reporting in cystic fibrosis over many years.16 Patient-reported HRQOL declines slowly over time at approximately 1% per year. Over a decade, population score decline was different for each CFQoL domain (Physical function-8.0, Social function-9.2, Emotional response-8.3, Treatment issues-13.7, Chest symptoms-9.4, Body image-6.0, Interpersonal relationships-6.8, Career concerns-15.9, Future concerns-13.2). Knowing the natural rate of change in HRQoL domains provides a benchmark against which changes due to CF complications or interventions can be compared and should help to inform the clinical relevance of HRQoL changes.

Previous work demonstrated that the FEV1% predicted and HRQoL declined slowly, however, a decrease in lung function was associated with a decrease in HRQoL over time.16 FEV1% predicted was significantly associated with all domains of HRQoL except Body image and these analyses have substantially supported that finding. Previously, it was reported that FEV1% declines on average by 8.8% and that Physical functioning declines on average by 8.0% for survivors over one decade. This accords with the results shown which indicate that a decade increase in age alone was associated with a 3.0–5.0% decline in Physical functioning. Additionally an 8.8% decline in FEV1% was associated with a 2.6–4.3% decline in physical functioning producing a total decline of between 5.6% and 9.3% in physical functioning; any small differences being due to the increased risk of change in clinical condition such as the onset of CFRD.

An improvement in HRQoL is a compelling argument for lung transplantation.22 23 Those in need of transplantation report restrictions on most aspects of their HRQoL.24 25 Generally, CF lung transplant recipients have been reported to have good outcomes with high levels of life quality in some HRQoL domains.26–28 However, longitudinal data comparing pre-transplantation and post-transplantation is lacking. The current modelling estimated the effect of undergoing a lung transplant on HRQoL by evaluating the change between the mean pre-transplantation and post-transplantation values. As expected, being listed for transplant predicted a profoundly negative impact on HRQoL. However, following transplantation only the domains of Treatment issues, Chest symptoms, Emotional functioning and Concerns for the future were radically improved. Transplant was associated with continuing poor HRQoL for Physical functioning, and a considerable further deterioration in Social functioning, Career concerns and perceived Body image. This highlights the importance of monitoring HRQoL over time.

Cross-sectional work highlighted a complex relationship between BMI, Body image and gender.4 These longitudinal data have clarified this matter. Women typically report a better body image than men4–7 29 and this association was confirmed from these longitudinal data. The model coefficient for gender for Body image was 0.58 (p<0.001) showing that women had a significantly higher Body image than men over time. However, the model coefficient for Body image for a 1 unit decrease in BMI was −0.154 for men and women combined (−0.159 for men and −0.162 for women separately), so although women have a higher level of Body image, a decrease of 1 unit BMI results in the same decrease in perceived Body image for men and women. Previous work had indicated that both men and women receiving nutritional interventions generally desired to be heavier, although women still only desired a BMI of 19.29 When BMI falls below what is desired, Body image HRQoL decreases for both genders. There was little negative impact on HRQoL as a result of nutritional interventions over time (oral nutritional supplements and enteral tube feeding), suggesting that the interventions to maintain BMI were successful. The single exception to this was the association between enteral tube feeds and Body image.

TIVADs have emerged as an effective means for intermittent venous access for therapeutic infusions30 nevertheless; having an access device predicted a poorer HRQoL for virtually all HRQoL domains over time. The reasons for this are unclear and we did not collect data on complication rates or the nature of complications. TIVADs provide the opportunity and social benefits of home intravenous therapy but Body image issues and the interference with daily activities (eg, car seatbelts, engaging in sport)31 remain a continuing concern.

CFRD is considered to be a condition in its own right. It is associated with a decrease in Social functioning, Chest symptoms, Body image and Emotional responses; although it is surprising that it does not predict a greater decline across HRQoL domains longitudinally. While it does not lessen the impact CFRD has on HRQoL, it is noteworthy that diabetes in people with CF has been shown to have a less negative impact on HRQoL than in those with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Both groups experienced hypoglycaemia, but loss of consciousness or needing help was more common in patients with T1DM and symptoms suggestive of hypoglycaemia were less of a problem for patients with CFRD in terms of severity, with patients with T1DM having more neuroglycopenic symptoms.32

B. cepacia complex had an immense negative impact on Social functioning and Body image, together with a considerable decline in Chest symptoms, Treatment issues and Physical functioning. This may be anticipated as during the collection of these data patients with B. cepacia complex were segregated at clinic, on wards and at scientific meetings.33 People with CF are aware of the associated increase in morbidity and mortality and the knowledge of colonisation with the bacteria brings further uncertainty about the future. Hence, one minor limitation of this study is that it started prior to the routine clinical classification of genomovar status, although this alone cannot predict clinical outcome in any individual patient.34

Further limitations are that this was a single-centre study and several important variables were not evaluated, including the frequency of pulmonary exacerbations35 and microbiological status (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, B. cepacia complex, genomovar classification, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis). The longitudinal data analysis showed that many more demographical and clinical variables were associated with HRQoL than in cross-sectional work. This was achieved by estimating coefficients that measured the different average level of HRQoL between all data recorded before and all data recorded after a change in a clinical variable. A limitation of this analysis was that it did not estimate HRQoL in relation to the time since the change occurred. So, for example, transplantation may have resulted in a relatively large decrease in a HRQoL domain for the first few years followed by recovery in the HRQoL subsequently. A more sophisticated analysis would be required to determine any such pattern.

The long-term determinants of life quality are becoming clearer and repeated HRQoL assessments should be able to provide useful information concerning the individual's adaptation to the disease and be used to improve the care delivered to patients. HRQoL measurement in CF remains largely a research endeavour, although monitoring HRQoL in routine clinical care has been shown to be feasible.12 Web-based completion of HRQoL scales may allow screening and the detection of problems, the monitoring of patient's difficulties over time, and improving clinician—patient communication by addressing these issues during a clinical consultation. Additionally, the input of these data into registries should enable robust evaluations of HRQoL over time and allow further evaluation of patient-reported outcomes in predicting morbidity and survival. The challenge for the future is to use the available information when designing and interpreting the results of studies, and to develop and evaluate psychological interventions that could improve HRQoL, or mitigate the effects of interventions known to impact adversely on HRQoL, for people with CF.

Footnotes

Contributors: JA involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting, revising and final approval of the article. AMM involved in the conception and design, acquisition of data, critical revision and final approval of the article. MAH involved in the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting, revising and final approval of the article. SPC involved in the conception and design, interpretation of data, critical revision and final approval of the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from Leeds research ethics committee and the University of Central Lancashire Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.UK Cystic Fibrosis Registry. Annual Data Report 2013. Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawicki GS, Sellers DE, Robinson WM. High treatment burden in adults with cystic fibrosis: challenges to disease self-management. J Cyst Fibros 2009;8:91–6. 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawicki GS, Tiddens H. Managing treatment complexity in cystic fibrosis: challenges and opportunities. Pediatr Pulmonol 2012;47:523–33. 10.1002/ppul.22546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gee L, Abbott J, Hart A et al. . Associations between clinical variables and quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2005;4:59–66. 10.1016/j.jcf.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitz TG, Henrich G, Goldbeck L. Quality of life with cystic fibrosis—aspects of age and gender. Klin Padiatr 2006;218:7–12. 10.1055/s-2004-832485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arrington-Sanders R, Yi MS, Tsevat J et al. . Gender differences in health-related quality of life of adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:5 10.1186/1477-7525-4-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gee L, Abbott J, Conway SP et al. . Quality of life in cystic fibrosis: the impact of gender, general health perceptions and disease severity. J Cyst Fibros 2003;2:206–13. 10.1016/S1569-1993(03)00093-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahl AK, Rustoen T, Hanestad BR et al. . Living with cystic fibrosis: impact on global quality of life. Heart Lung 2005;34:324–31. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quittner A, Buu A, Messer M et al. . Development and validation of the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire in the United States: a health-related quality-of-life measure for cystic fibrosis. Chest 2005;128:2347–54. 10.1378/chest.128.4.2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staab D, Wenninger K, Gerbert N et al. . Quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis and their parents; what is important besides disease severity. Thorax 1998;53:727–31. 10.1136/thx.53.9.727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley J, McAlister O, Elborn S. Pulmonary function, inflammation, exercise capacity and quality of life in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2001;17:712–15. 10.1183/09031936.01.17407120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldbeck L, Zerrer S, Schmitz TG. Monitoring quality of life in outpatients with cystic fibrosis: feasibility and longitudinal results. J Cyst Fibros 2007;6:171–8. 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawicki GS, Rasouliyan L, McMullen AH et al. . Longitudinal assessment of health-related quality of life in an observational cohort of patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2011;46:36–44. 10.1002/ppul.21325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dill EJ, Dawson R, Sellers DE et al. . Longitudinal trends in health-related quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. Chest 2013;144:981–9. 10.1378/chest.12-1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott J, Hart A, Morton AM et al. . Can health-related quality of life predict survival in adults with cystic fibrosis. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2009;179:54–8. 10.1164/rccm.200802-220OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbott J, Hurley MA, Morton AM et al. . Longitudinal association between lung function and health-related quality of life in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2013;68:149–54. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gee L, Abbott J, Conway S et al. . Development of a disease specific health related quality of life measure for adults and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2000;55:946–54. 10.1136/thorax.55.11.946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Wiley Series in Probability. 2nd edn New Jersey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreft I, De Leeuw J. Introducing multilevel modelling. London: Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walters SJ. Quality of Life Outcomes in Clinical Trials and Health Care Evaluation: a practical guide to health care interpretation. Chichester: Wiley, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasbash J, Charlton C, Browne WJ et al. . MLwiN version 2.1. centre for multilevel modelling. University of Bristol, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spahr JE, Love RB, Francois M et al. . Lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis: current concepts and one center's experience. J Cyst Fibros 2007;6:334–50. 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quattrucci S, Rolla M, Cimino G et al. . Lung transplant for cystic fibrosis: 6-year follow-up. J Cyst Fibros 2005;4:107–14. 10.1016/j.jcf.2005.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feltrim MIZ, Rozanski A, Borges ACS et al. . The quality of life of patients on the lung transplantation waiting list. Transplant Proc 2008;40:819–21. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor JL, Smith PJ, Babyak MA et al. . Coping and quality of life in patients awaiting lung transplantation. J Psychsom Res 2008;64:71–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kugler C, Fischer S, Gottlieb J et al. . Health-related quality of life in two hundred-eighty lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:2262–8. 10.1016/j.healun.2005.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smeritschnig B, Jaksch P, Kocher A et al. . Quality of life after lung transplantation: a cross-sectional study. Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:474–80. 10.1016/j.healun.2003.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ullrich G, Jaensch H, Niedermeyer J. Quality of life in young adults after lung transplantation: Only a matter of improved performance? Transplant Med 2004;16:202. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbott J, Conway S, Etherington C et al. . Nutritional status, perceived body image and eating behaviours in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin Nutr 2007;26:91–9. 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.A-Rahman AKM, Spencer D. Totally implantable vascular access devices for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(3):CD004111 10.1002/14651858.CD004111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodgers HC, Liddle K, Nixon SJ et al. . Totally implantable venous access devices in cystic fibrosis: complications and patients’ opinions. Eur Respir J 1998;12:217–20. 10.1183/09031936.98.12010217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tierney S, Deaton C, Webb K et al. . Living with cystic fibrosis-related diabetes or type 1 diabetes mellitus: a comparative study exploring health-related quality of life and patients’ reported experiences of hypoglycaemia. Chronic Illn 2008;4:278–88. 10.1177/1742395308094240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duff AJA. Psychological consequences of segregation resulting from chronic Burkholderia cepacia infection in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2002;57:756–8. 10.1136/thorax.57.9.756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowton K, Gabe J. Cystic fibrosis adults’ perception and management of the risk of infection with Burkholderia cepacia complex. Health Risk Soc 2006;8:395–415. 10.1080/13698570601008263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradley JM, Blume SW, Balp MM et al. . Quality of life and healthcare utilisation in cystic fibrosis: a multicentre study. Eur Respir J 2013;41:571–7. 10.1183/09031936.00224911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]