Abstract

Objective

To study the prevalence of tobacco use among teenagers, to evaluate a tobacco prevention programme and to study factors related to participation in the prevention programme.

Design and setting

Population-based prospective cohort study.

Method

Within the Obstructive Lung disease in Northern Sweden (OLIN) studies, a cohort study about asthma in schoolchildren started in 2006. All children aged 7–8 years in three municipalities were invited to a questionnaire survey and 2585 (96%) participated. The cohort was followed up at age 11–12 years (n=2612, 95% of invited) and 14–15 years (n=2345, 88% of invited). In 2010, some of the children in the OLIN cohort (n=447) were invited to a local tobacco prevention programme and 224 (50%) chose to participate.

Results

At the age of 14–15 years, the prevalence of daily smoking was 3.5%. Factors related to smoking were female sex, having a smoking mother, participation in sports and lower parental socioeconomic status (SES). The prevalence of using snus was 3.3% and risk factors were male sex, having a smoking mother, having a snus-using father and non-participation in the prevention programme. In the prevention programme, the prevalence of tobacco use was significantly lower among the participants compared with the controls in the cohort. Factors related to non-participation were male sex, having a smoking mother, lower parental SES and participation in sports.

Conclusions

The prevalence of tobacco use was lower among the participants in the tobacco prevention programme compared with the non-participants as well as with the controls in the cohort. However, the observed benefit of the intervention may be overestimated as participation was biased by selection.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This paper presents data from a prospective cohort study with high response rates and few participants lost to follow-up.

A validated questionnaire about asthma and respiratory symptoms was used.

Collaboration with a tobacco prevention programme (Tobacco Free Duo) enabled us to combine the longitudinal data from the Obstructive Lung disease in Northern Sweden (OLIN) studies with intervention data on participation in the prevention programme.

We lack information about the level of activity in the tobacco prevention programme during the follow-up time.

Self-reported smoking was not validated by objective measures.

Introduction

Smoking is the single most important and preventable risk factor for all respiratory symptoms and a large number of diseases. Although the health consequences are well known, smoking is still common.1 Daily smoking is usually established during the teen years, most commonly between 14 and 17 years of age,2 and rarely after the age of 24.3 Although Sweden is often mentioned as a country with a decreasing prevalence of smokers and high quit rates among adults,4 the decrease in smoking prevalence among teenagers has been limited.5 Therefore, reducing smoking in teenagers is an important public health matter.

In the last decades, a wide range of prevention efforts have been carried out in order to reduce smoking among teenagers.6–10 A key factor for successful prevention is the long-term collaboration between national, regional and local organisations. On the national and regional levels, smoking bans in schools,11 and combination approaches that include policies, media campaigns and school-based programmes,12 have been shown to be effective methods to decrease smoking among adolescents. However, many prevention efforts aimed at teenagers are voluntary and participation may be affected by selection bias if those with the greatest need of the intervention choose not to participate. Among adults, it is known that the prevalence of smokers is higher among non-participants in questionnaire surveys regarding respiratory conditions13–15 and in health promotion interventions.16 However, few studies have reported on factors related to non-participation in tobacco intervention among teenagers. One available study showed that non-participation in a family-directed tobacco and alcohol prevention programme was related to male sex, lower parental education and parental smoking.17

The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence of tobacco use among teenagers and to evaluate the outcome of a school-based voluntary tobacco prevention programme for teenagers. Further, factors related to participation in the prevention programme were investigated.

Methods

Study population

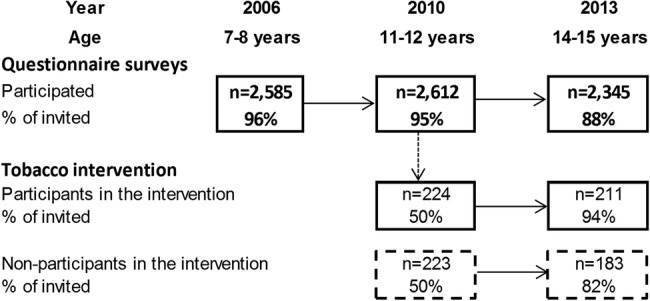

As a part of the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden (OLIN) studies, a population-based paediatric cohort was recruited in 2006. The parents to all children in first and second grade (age 7–8 years) in three municipalities of northern Sweden: Luleå, Piteå and Kiruna, were invited to complete a questionnaire and 2585 participated (96% of invited).18 19 Four years later, at the age of 11–12 years, the parents were invited to a follow-up questionnaire survey using the same methods, and 2612 completed the questionnaire (95% of invited). At the age of 14–15 years, those who had participated in any of the previous two surveys were reinvited (n=2657) and 2345 participated (88.3%; figure 1). In this latter survey the questionnaire was completed by the teenagers.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design and participation in a cohort study about asthma and allergic diseases, and in a tobacco prevention programme.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire included the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) core questionnaire.20 It was expanded with additional questions about asthma and allergic diseases including physician diagnoses, symptoms, use of medicine and heredity. Other questions included possible risk factors such as living conditions, physical activity, parental smoking and socioeconomic status (SES).19 In the questionnaire completed by the teenagers at the age of 14–15 years, questions about tobacco use were added.

The tobacco prevention programme

Tobacco Free Duo is a long-term school-based tobacco prevention programme with the aim to prevent tobacco use initiation during teen years.7 At the end of sixth grade, a teenager had the opportunity to team up with an adult. The pair signed a contract to stay tobacco free for the next 3 years. The prevention programme included information to increase knowledge and awareness on tobacco-related issues, to the teenagers as well as to the adults. It also included an annual assurance of fulfilment of the contract after grade 7, 8 and 9, and positive reinforcements to the participants. An evaluation of Tobacco Free Duo in Västerbotten county, Sweden, showed significantly lower prevalence of smoking in the intervention schools compared with control schools.7

In 2010, Tobacco Free Duo was initiated in several municipalities in Norrbotten county, including Luleå and Kiruna; two of the OLIN study areas. It was up to the schools to decide whether they wanted to participate in the prevention programme. The children in 13 schools in Kiruna (n=360) and 4 schools in Luleå (n=87) were invited to participate by signing the contract at the age of 12 years (figure 1). A collaboration between the OLIN studies and Tobacco Free Duo enabled a joint database with data on participation in the prevention programme and longitudinal questionnaire data from the OLIN studies.

Definitions

Participants: those who attended a school in the study area that was invited to participate in Tobacco Free Duo, and chose to sign the contract to participate at the age of 12 years.

Non-participants: those who attended a school in the study area that was invited to participate in Tobacco Free Duo, but chose not to participate.

Controls: those who attended the schools in the study area that were not invited to Tobacco Free Duo.

Snus: moist ground tobacco which is placed under the upper lip.

Any smoking/snus use: those reporting smoking/snus use daily, weekly or monthly. Classification of SES was based on parental occupation according to a system developed by Statistics Sweden.21 The highest level of SES among the adults in the household was chosen. In an aggregated form, the classification consisted of six groups of occupationally active persons, and one group of non-active persons as follows: (1) professionals and executives; (2) self-employed; (3) intermediate non-manual employees; (4) assistant non-manual employees; (5) manual workers in industry; (6) manual workers in service; (7) unemployed, including students, retired and housewives.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were made using the computer software IBM SPSS Statistics (V.22.0; IBM SPSS Statistics, New York, USA). For assessment of differences between groups, χ2 tests were used and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Dependent variables were smoking and use of snus, respectively, at the age of 15 years, and participation in the tobacco prevention programme from the age of 12 years. Independent variables included sex, having smoking or snus-using parents, living conditions, participation in sports and parental SES. Significant and borderline significant factors identified in the bivariate analyses were included in multivariate analyses, which were performed by multiple logistic regression analysis and expressed as ORs with 95% CIs.

Results

Prevalence of tobacco use at the age of 14–15 years

The prevalence of any smoking was 5.9%, with no statistical difference by sex. Any snus use was 4.7%, and significantly more common among boys than girls (7.2% and 1.9%, p<0.001). The prevalence of monthly smoking was 1.5%, weekly smoking was 0.9%, monthly use of snus was 0.9% and weekly snus use was 0.5%.

The prevalence of daily smoking in the cohort was 3.5%, and significantly higher among the girls than among boys (table 1). For daily snus use, the overall prevalence was 3.3%, significantly more common among boys. The prevalence of daily smoking and the use of snus were both significantly lower compared with the prevalence in a similar cohort, surveyed 10 years previously in the same study area. At that survey, the prevalence of daily smoking was 5.8% and using snus, 9.9%.9 In the present study, the prevalence of daily smoking and daily use of snus, respectively, was significantly higher among those with smoking or snus-using parents, living in an apartment, living in a single parent household, not participating in sports and among those with lower parental SES (table 1). There were no significant differences in the prevalence of smoking or snus use related to urban or rural living, having older siblings, having physician-diagnosed asthma or a positive skin prick test.

Table 1.

Prevalence (%) of tobacco use in relation to demographic factors, at the age of 14–15 years

| Smoking |

Snus use |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

Bivariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

| Daily smoking (%) | Difference p value | OR | 95% CI | Daily use of snus (%) | Difference p value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Boys | 2.7 | 1.00 | 5.5 | 5.72 | 2.76 to 11.85 | |||

| Girls | 4.4 | 0.021 | 1.95 | 1.11 to 3.41 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| Tobacco intervention | ||||||||

| Control | 3.5 | 1.00 | 3.1 | 1.00 | ||||

| Participant | 0.9 | 0.20 | 0.03 to 1.48 | 0.9 | 0.53 | 0.12 to 2.27 | ||

| Non-participant | 4.9 | 0.073 | 1.26 | 0.51 to 3.16 | 7.7 | 0.023 | 2.14 | 1.05 to 4.37 |

| Mother smoking | ||||||||

| No | 2.5 | 2.5 | ||||||

| Yes | 10.1 | <0.001 | 2.46 | 1.29 to 4.68 | 8.4 | <0.001 | 3.38 | 1.76 to 6.50 |

| Father smoking | ||||||||

| No | 2.6 | 3.0 | ||||||

| Yes | 10.2 | <0.001 | 1.79 | 0.93 to 3.45 | 5.6 | 0.023 | 0.76 | 0.34 to 1.66 |

| Mother using snus | ||||||||

| No | 3.1 | 2.7 | ||||||

| Yes | 6.7 | 0.005 | 1.19 | 0.54 to 2.64 | 8.0 | <0.001 | 1.72 | 0.85 to 3.48 |

| Father using snus | ||||||||

| No | 2.5 | 1.8 | ||||||

| Yes | 5.8 | <0.001 | 1.65 | 0.94 to 2.90 | 6.6 | <0.001 | 3.20 | 1.81 to 5.64 |

| Living conditions | ||||||||

| House | 3.1 | 1.00 | 2.7 | 1.00 | ||||

| Apartment | 5.9 | 0.79 | 0.38 to 1.63 | 6.1 | 1.78 | 0.91 to 3.47 | ||

| Both | 2.6 | 0.026 | 0.75 | 0.21 to 2.71 | 1.7 | 0.002 | 0.32 | 0.04 to 2.49 |

| Single parent household | 7.4 | 1.34 | 0.64 to 2.81 | 6.4 | 1.07 | 0.49 to 2.34 | ||

| Two parent household | 3.0 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 2.8 | 0.001 | 1.00 | ||

| Participation in sports | ||||||||

| No | 7.8 | 1.00 | 4.9 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 1.8 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 0.17 to 0.52 | 2.7 | 0.006 | 0.67 | 0.39 to 1.18 |

| Parental socioeconomic status | ||||||||

| Professionals | 0.8 | 1.00 | 2.1 | 1.00 | ||||

| Self-employed | 7.2 | 6.07 | 1.70 to 21.72 | 3.2 | 0.90 | 0.23 to 3.50 | ||

| Intermediate non-manual | 1.9 | 2.22 | 0.68 to 7.25 | 2.8 | 1.25 | 0.53 to 2.94 | ||

| Assistant non-manual | 3.7 | 3.65 | 1.09 to 12.21 | 2.6 | 0.75 | 0.24 to 2.37 | ||

| Manual workers industry | 5.6 | 4.57 | 1.44 to 14.47 | 4.9 | 1.58 | 0.64 to 3.93 | ||

| Manual workers service | 4.4 | 3.06 | 0.89 to 10.50 | 5.6 | 1.63 | 0.63 to 4.22 | ||

| Unemployed | 20.0 | <0.001 | 14.21 | 3.49 to 57.84 | 5.0 | 0.005 | 0.80 | 0.14 to 4.60 |

Significant factors in the bivariate analyses were included in a multiple logistic regression analysis and expressed as ORs with 95% CI.

In a multivariate analysis, daily smoking was related to female sex; having a smoking mother; a smoking father; not participating in sports; and parental SES of self-employed, assistant non-manual, manual worker in industry and unemployed. Daily use of snus was related to male sex, having a smoking mother and having a father who used snus (table 1).

Participation in the tobacco prevention programme

The children in the participating schools (n=447) were compared with children in non-participating schools (n=2165). There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of male sex, parental smoking, living conditions, physician-diagnosis of asthma, participation in sports or parental SES between the sample invited to the tobacco prevention programme and the controls who were not invited. However, among those invited to the prevention programme, the prevalence of urban living (81% vs 58%, p<0.001), and having older siblings (67% vs 62%, p=0.047) was significantly higher compared with the controls. Among the 447 invited to join the prevention programme, 224 (50%) chose to participate by signing a contract. Comparison of baseline characteristics between participants and non-participants in the tobacco prevention programme is presented in table 2. Comparing non-participants with participants, the prevalence of boys (59% vs 43%), having a smoking mother (20% vs 9%) and living in a single parent household (16% vs 8%) was significantly higher among the non-participants, while fewer non-participants were taking part in sports (65% vs 79%). Among the participants, it was more common to have parental SES at the professional and assistant non-manual level, while among non-participants, parental SES from among intermediate non-manual and manual workers, in industry and service level, was more common (test-for-trend p<0.005). There were no significant differences between participants and non-participants regarding living in a house versus living in an apartment, urban versus rural living, having older siblings, or having physician-diagnosed asthma.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics at the age of 11–12 years among the participants and non-participants in a tobacco prevention programme

| Participants n=224 (%) | Non-participants n=223 (%) | Difference p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 42.9 | 59.2 | 0.001 |

| Smoking mother | 9.0 | 20.4 | 0.001 |

| Smoking father | 10.5 | 8.2 | 0.412 |

| Living conditions | |||

| House | 75.5 | 69.0 | |

| Apartment | 20.5 | 25.8 | |

| Both | 4.1 | 5.2 | 0.326 |

| Urban | 80.0 | 78.9 | |

| Rural | 19.5 | 19.1 | 0.530 |

| Single parent household | 7.6 | 15.7 | 0.008 |

| Having older siblings | 62.4 | 70.0 | 0.094 |

| Physician-diagnosed asthma | 13.5 | 14.1 | 0.846 |

| Participation in sports | 78.5 | 65.3 | 0.002 |

| Parental socioeconomic status | |||

| Professionals | 28.0 | 18.1 | |

| Self-employed | 6.4 | 6.0 | |

| Intermediate non-manual | 28.0 | 32.4 | |

| Assistant non-manual | 15.1 | 10.6 | |

| Manual workers industry | 14.2 | 16.7 | |

| Manual workers service | 6.9 | 13.4 | |

| Unemployed | 1.4 | 2.8 | 0.005 |

Significant factors related to non-participation in the tobacco prevention programme identified in the bivariate analyses were included in a multivariate analysis. Non-participation was related to male sex (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.7), having a smoking mother (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.8) and parental SES of manual workers in service (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.3 to 6.7). Participation in sports was inversely related to non-participation (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.9; table 3).

Table 3.

Factors related to non-participation in a tobacco prevention programme, analysed by multiple logistic regression and expressed as ORs with 95% CI

| Non-participation |

||

|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | |

| Male sex | 1.81 | 1.20 to 2.74 |

| Smoking mother | 2.05 | 1.09 to 3.84 |

| Single parent household | 1.78 | 0.90 to 3.51 |

| Participation in sports | 0.55 | 0.34 to 0.89 |

| Parental socioeconomic status | ||

| Professionals | 1.00 | |

| Self-employed | 1.06 | 0.43 to 2.63 |

| Intermediate non-manual | 1.56 | 0.90 to 2.71 |

| Assistant non-manual | 0.85 | 0.42 to 1.72 |

| Manual workers industry | 1.37 | 0.70 to 2.70 |

| Manual workers service | 2.98 | 1.32 to 6.74 |

| Unemployed | 2.87 | 0.25 to 33.38 |

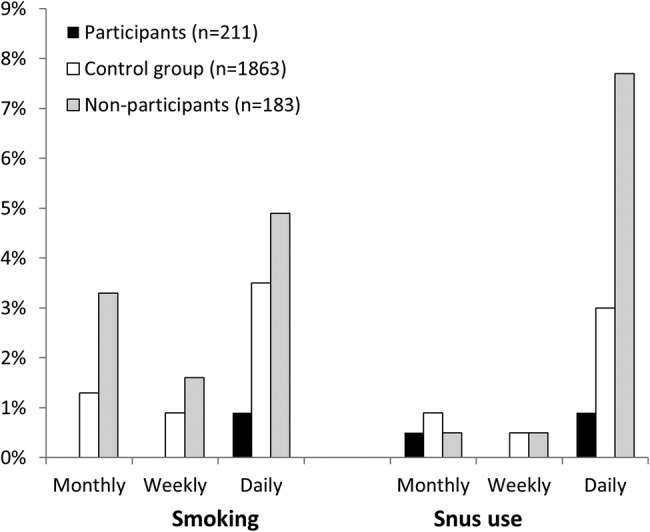

Effect of the intervention

The prevalence of smoking and use of snus was significantly lower among the participants in the prevention programme compared with the non-participants and the controls in the rest of the cohort (figure 2). Of the participants in the programme, only four individuals were daily smokers or snus users at the age of 14–15 years. On the school level, there was no spill-over effect, that is, there was no difference in tobacco use between the children at the invited schools and the control schools.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of tobacco use at the age of 14–15 years among participants and non-participants in the prevention programme and among the controls in the rest of the cohort. Test for trend: participants versus non-participants: smoking p<0.001; snus p<0.001. Participants versus controls: smoking p=0.007; snus p=0.026. Non-participants versus controls: smoking p=0.054; snus p=0.002.

Among the controls at baseline at the age of 11–12 years, the prevalence of having a smoking mother was 14.4%, and 11.4% had a smoking father. In the follow-up, the corresponding proportions were very similar: 13.4% and 12.4%, respectively. However, among the participants in the intervention, the prevalence of having a smoking mother decreased from 9.0% to 5.8% (p=0.201), while having a smoking father remained similar, 10.5% and 11.5%. However, none of these differences in prevalence were statistically significant.

Discussion

In this population-based prospective study, we report a low prevalence of tobacco use among Swedish teenagers, especially among the participants in a tobacco prevention programme. Further, we found that participation in the prevention programme was affected by a selection bias, as those in most need of smoking prevention, that is, children having smoking parents and a lower SES, did not participate.

From the 1980s to the 2000s, smoking steadily decreased among Swedish adults,22 23 while the prevalence of smoking initiation among teenagers remained relatively stable.5 However, in the last decade there have been some reports of a decrease also among teenagers. In 2003, the prevalence of daily smoking at the age of 14–15 years was 5.8% and using snus 9.9% in a similar cohort in the same study area,9 compared with 3.5% and 3.3%, respectively, in the present study. Thus, smoking and the use of snus had both decreased, a positive result in accordance with recent nationwide reports among Swedish5 and Norwegian teenagers.24

Despite the low prevalence of tobacco use, some teenagers were more likely to be tobacco users than others. Smoking was related to socioeconomic factors such as parental socioeconomic level, living in a single parent household and living in an apartment, in accordance with other studies.9 24–26 There are socioeconomic inequalities in health,27 and the fact that smoking is more common among those with lower socioeconomic level contributes to these inequalities.24 28 Other factors related to smoking were female sex, having smoking family members and not taking part in sports, as shown in other studies.9 29 30 Few studies have reported on factors related to snus use among teenagers.9 Similar to other studies,29 the risk factors for using snus were male sex and parental tobacco use. Additionally, we found a significant association between snus use and parental SES of manual workers in industry and in service. However, in the multivariate analysis, this association lost significance. It has been shown that lower educational level and income was related to snus use among adults in Sweden.31

By identification and characterisation of tobacco users, and also populations at risk of becoming tobacco users, prevention efforts might be improved. Because parental tobacco use is an important risk factor for tobacco use among teenagers,9 29 the study design of the present prevention programme (Tobacco free Duo) included the partnership with a tobacco-free adult. In an evaluation of Tobacco Free Duo in another county in Sweden, it was shown that the prevalence of smoking not only decreased among the teenagers, but also among the adult participants in the programme.32 This was also seen in our study, but the decrease was not statistically significant. Having tobacco-free role models is an important aspect of tobacco prevention among teenagers.

In studies among adults, non-participation in studies about respiratory conditions is associated with higher prevalence of smoking13 14 33 and lower SES.16 Further, non-participation in an alcohol use prevention study among teenagers was related to lower parental socioeconomic level.34 However, little is known about non-participation in smoking prevention programmes among teenagers. In a review of the long-term effects of smoking prevention programmes, the authors noted a selection bias, as most reviewed programmes were based on convenience samples and not random samples.35 This may impact the external validity of a study because the sample may not be representative of the general population. Further, it has been shown that having smoking family members decreased the efficacy of a school-based smoking prevention programme.36 Thus, involving the family in smoking prevention seems to be a good idea. However, although the prevention programme in our study involved the child and an adult, and was a collaboration between schools, Norrbotten county council and local organisations, the participation rate was low, as only 50% chose to join the programme. Furthermore, the prevalence of having a smoking mother was twice as high among the non-participants compared with the participants. Thus, many of those who would have benefited from the prevention efforts chose not to participate. Another factor related to non-participation was parental SES of manual workers in service. One explanation for this finding may be that manual workers in service as well as smoking are more common among women, in this case the mothers, and both these factors were related to non-participation.

We suggest that in order to avoid this bias and improve the efficacy of smoking prevention, even closer collaboration between policymakers, community, school and the family is needed. If we succeed in reaching and informing these actors, the prevention strategies may target a larger population. Further, as most of the teenagers were at a low risk of becoming smokers, the ‘prevention paradox’ may apply, similar to smoking cessation intervention among smokers.37 It states that prevention strategies on the population level are more likely to reduce the smoking-related health problems in the population compared with strategies on the individual level. Although strategies on the individual level may target teenagers at high risk of becoming smokers, these individuals are relatively few and only account for a minority of the overall public health burden. Prevention strategies on the population level are said to be more effective, simply because they reach a higher number of individuals. Promising prevention strategies that have been suggested, aimed at teenagers, include media campaigns, increasing cigarette price and restricting access to tobacco products, and also social environment changes such as reduction of smoking among adult role models.38

The strengths of this study included the longitudinal study design, with high response rates, few participants lost to follow-up and the use of validated questionnaires. Further, the collaboration with the prevention programme, Tobacco Free Duo, enabled us to combine the longitudinal data from the OLIN studies with intervention data on participation in the prevention programme. A limitation of the study included the lack of information about the level of activity in the tobacco prevention programme during the follow-up time. Another limitation is that self-reported smoking was not validated by objective measures. However, others that compared self-reports of smoking with cotinine levels in saliva found good agreement.39

In conclusion, prevalence of tobacco use was significantly lower among the participants in the tobacco prevention programme compared with the controls, after 3 years. However, the observed benefit of the intervention may be overestimated as the participation was related to a selection bias, as those in most need of smoking prevention, that is, children having smoking parents and a lower SES, did not participate. One way to improve the efficacy of smoking prevention efforts is to have even closer collaboration between policymakers, community, school and the family. Developing comprehensive strategies for including more high-risk children in prevention efforts at the population level will be an important measure to reduce tobacco use among teenagers.

Acknowledgments

Sigrid Sundberg, Sven-Arne Jansson, Pia Johansson and Bodil Larsson are acknowledged for data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: LH was responsible for the study design, collected the data, performed the statistical analyses, drafted and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. MA and CS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. ER was responsible for study conception and design, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (grant number 20100307); The Swedish Asthma-Allergy Foundation (grant number 2013036); Visare Norr (grant number 217341); and Norrbotten County Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethical Review Board at Umeå University, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. 2013.

- 2.Edvardsson I, Lendahls L, Håkansson A. When do adolescents become smokers? Annual seven-year population-based follow-up of tobacco habits among 2000 Swedish pupils––an open cohort study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2009;27:41–6. 10.1080/02813430802588675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards R, Carter K, Peace J et al. . An examination of smoking initiation rates by age: results from a large longitudinal study in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Public Health 2013;37:516–19. 10.1111/1753-6405.12105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaap MM, Kunst AE, Leinsalu M et al. . Effect of nationwide tobacco control policies on smoking cessation in high and low educated groups in 18 European countries. Tob Control 2008;17:248–55. 10.1136/tc.2007.024265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gripe I. Skolelevers drogvanor. 2013;139. The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs.

- 6.Sherman EJ, Primack BA. What works to prevent adolescent smoking? A systematic review of the National Cancer Institute's Research-Tested Intervention Programs. J Sch Health 2009;79:391–9. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00426.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson M, Stenlund H, Bergström E et al. . It takes two: reducing adolescent smoking uptake through sustainable adolescent-adult partnership. J Adolesc Health 2006;39:880–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller-Riemenschneider F, Bockelbrink A, Reinhold T et al. . Long-term effectiveness of behavioural interventions to prevent smoking among children and youth. Tob Control 2008;17:301–12. 10.1136/tc.2007.024281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedman L, Bjerg A, Perzanowski M et al. . Factors related to tobacco use among teenagers. Respir Med 2007;101:496–502. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jepson RG, Harris FM, Platt S et al. . The effectiveness of interventions to change six health behaviours: a review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2010;10:538 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-538 10.1186/1471-2458-10-538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnohr C, Kreiner S, Rasmussen M et al. . The role of national policies intended to regulate adolescent smoking in explaining the prevalence of daily smoking: a study of adolescents from 27 European countries. Addiction 2008;103:824–31. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backinger C, Fagan P, Matthews E et al. . Adolescent and young adult tobacco prevention and cessation: current status and future directions. Tob Control 2003;12:iv46–53. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rönmark E, Ekerljung L, Lötvall J et al. . Large scale questionnaire survey on respiratory health in Sweden: effects of late- and non-response. Respir Med 2009;103:1807–15. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eagan T, Eide G, Gulsvik A et al. . Nonresponse in a community cohort study: predictors and consequences for exposure-disease associations. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:775–81. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00431-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotaniemi J, Hassi J, Kataja M et al. . Does non-responder bias have a significant effect on the results in a postal questionnaire study? Eur J Epidemiol 2001;17:809–17. 10.1023/A:1015615130459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vehtari A, Reijonsaari K, Kahilakoski OP et al. . The influence of selective participation in a physical activity intervention on the generalizability of findings. J Occup Environ Med 2014;56:291–7. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauman KE, Ennett ST, Foshee VA et al. . Correlates of participation in a family-directed tobacco and alcohol prevention program for adolescents. Health Educ Behav 2001;28:440–61. 10.1177/109019810102800406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjerg A, Sandström T, Lundbäck B et al. . Time trends in asthma and wheeze in Swedish children 1996–2006: prevalence and risk factors by sex. Allergy 2010;65:48–55. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rönmark E, Bjerg A, Perzanowski M et al. . Major increase in allergic sensitization in schoolchildren from 1996 to 2006 in northern Sweden. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:357–63. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asher M, Keil U, Anderson H et al. . International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J 1995;8:483–91. 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statistics Sweden. Socio-economic classification. MIS, 1982:4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Backman H, Hedman L, Jansson SA et al. . Prevalence trends in respiratory symptoms and asthma in relation to smoking—two cross-sectional studies ten years apart among adults in northern Sweden. World Allergy Organ J 2014;7:1 -4551-7-1 10.1186/1939-4551-7-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodu B, Jansson JH, Eliasson M. The low prevalence of smoking in the Northern Sweden MONICA study, 2009. Scand J Public Health 2013;41:808–11. 10.1177/1403494813504836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Soest T, Pedersen W. Hardcore adolescent smokers? An examination of the hardening hypothesis by using survey data from two Norwegian samples collected eight years apart. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:1232–9. 10.1093/ntr/ntu058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellickson P, Tucker J, Klein D. Reducing early smokers’ risk for future smoking and other problem behavior: insights from a five-year longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health 2008;43:394–400. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jefferis B, Power C, Graham H et al. . Effects of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on persistent smoking. Am J Public Health 2004;94:279–85. 10.2105/AJPH.94.2.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ et al. . Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2468–81. 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercken L, Moore L, Crone MR et al. . The effectiveness of school-based smoking prevention interventions among low- and high-SES European teenagers. Health Educ Res 2012;27:459–69. 10.1093/her/cys017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosendahl KI, Galanti MR, Gilljam H et al. . Smoking mothers and snuffing fathers: behavioural influences on youth tobacco use in a Swedish cohort. Tob Control 2003;12:74–8. 10.1136/tc.12.1.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Escobedo L, Marcus S, Holtzman D et al. . Sports participation, age at smoking initiation, and the risk of smoking among US high school students. JAMA 1993;269:1391–5. 10.1001/jama.1993.03500110059035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norberg M, Malmberg G, Ng N et al. . Who is using snus?—Time trends, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics of snus users in the ageing Swedish population. BMC Public Health 2011;11:929 -2458-11-929 10.1186/1471-2458-11-929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsson M, Stenlund H, Weinehall L et al. . “I would do anything for my child, even quit tobacco”: bonus effects from an intervention that targets adolescent tobacco use. Scand J Psychol 2009;50:341–5. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rönmark E, Lundqvist A, Lundbäck B et al. . Non-responders to a postal questionnaire on respiratory symptoms and diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 1999;15:293–9. 10.1023/A:1007582518922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettersson C, Linden-Boström M, Eriksson C. Reasons for non-participation in a parental program concerning underage drinking: a mixed-method study. BMC Public Health 2009;9:478 -2458-9-478 10.1186/1471-2458-9-478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skara S, Sussman S. A review of 25 long-term adolescent tobacco and other drug use prevention program evaluations. Prev Med 2003;37:451–74. 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00166-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hruba D, Zaloudikova I. What limits the effectiveness of school-based anti-smoking programmes? Cent Eur J Public Health 2012;20:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stockwell T, Toumbourou JW, Letcher P et al. . Risk and protection factors for different intensities of adolescent substance use: when does the Prevention Paradox apply? Drug Alcohol Rev 2004;23:67–77. 10.1080/09595230410001645565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE et al. . Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob Control 2000;9:47–63. 10.1136/tc.9.1.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Post A, Gilljam H, Rosendahl I et al. . Validity of self reports in a cohort of Swedish adolescent smokers and smokeless tobacco (snus) users. Tob Control 2005;14:114–17. 10.1136/tc.2004.008789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]