Abstract

Introduction

The rate of intravenous thrombolysis with tissue-type plasminogen activator or urokinase for stroke patients is extremely low in China. It has been demonstrated that a telestroke service may help to increase the rate of intravenous thrombolysis and improve stroke care quality in local hospitals. The aim of this study, also called the Acute Stroke Advancing Program, is to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of decision-making concerning intravenous thrombolysis via a telemedicine consultation system for acute ischaemic stroke patients in China.

Methods and analysis

This is a multicentre historically controlled study with a planned enrolment of 300 participants in each of two groups. The telestroke network consists of one hub hospital and 14 spoke hospitals in underserved regions of China. The usual stroke care quality in the spoke hospitals without guidance from the hub hospital will be used as the historical control. The telemedicine consultation system is an interactive, two-way, wireless, audiovisual system accessed on portable devices. The primary outcome is the percentage of patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis within 4.5 h of stroke onset.

Ethics and dissemination

The project has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Xijing Hospital. The results will be published in scientific journals and presented to local government and relevant institutes.

Trial registration number

NCT02088346 (12 March 2014).

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Acute Stroke Advancing Program using Telemedicine (ASAP-Tel) is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of decision-making regarding intravenous thrombolysis via a telemedicine consultation system for acute ischaemic stroke patients in China.

Our telemedicine consultation system is different from most other telestroke studies in that it is based on easily portable devices such as tablet computers and smartphones.

This system may help to increase the rate of intravenous thrombolysis and improve stroke care quality in local hospitals.

The main limitation of this study is that it is a historically controlled study, which may introduce some bias.

Introduction

For patients with ischaemic stroke, the use of intravenous (IV) thrombolysis with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) within 4.5 h has been widely accepted as beneficial, based on the results of several trials.1–6 In China, in addition to rt-PA, IV urokinase within 6 h has also been approved by the China Food and Drug Administration, recommended by the 2010 Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke,7 and supported by evidence from two IV urokinase thrombolysis trials which have explored the doses, efficacy and safety of IV urokinase in patients with acute ischaemic stroke.8 9 Urokinase is used more frequently than rt-PA, mainly because it is cheaper and because rt-PA is not covered by medical insurance in China. Eligible patients in our study will be able to choose to receive either rt-PA or urokinase.

The rate of IV thrombolysis with rt-PA or urokinase is extremely low in China. One epidemiological investigation of 35 hospitals in 15 Chinese cities from 2002 to 2003 revealed that the rate of thrombolysis within 6 h of stroke onset was only 6.7%.10 In 2011, Wang et al11 reviewed results from the Chinese National Stroke Registry (including 132 urban hospitals), and found that from September 2007 to August 2008, only 7.2% of 2514 ischaemic stroke patients who presented to the emergency department (ED) within 3 h of stroke onset were treated with IV rt-PA. This poor situation is mainly due to the fact that the local hospitals who first treat stroke patients usually lack stroke expertise and infrastructure.12

In the past decade, telestroke services have been widely employed in North America and Europe,13 14 helping to resolve the shortage of neurological expertise, and enabling thrombolytic therapy to be administered in non-specialised hospitals.13 15–17 There is positive evidence that telestroke services are safe and comparable in quality to those provided face-to-face.18 19 In 2005, the Telemedical Pilot Project for Integrative Stroke Care in Bavaria (TEMPiS) explored the use of IV rt-PA in non-urban areas through a telemedicine system. In this study, symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage (sICH) occurred in 8.5% of patients and in-hospital mortality was 10.4%,20 which were similar to the rates reported in the NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) trial. A retrospective review identified 296 stroke patients receiving IV rt-PA within 3 h either at a spoke hospital (61.1%) or at the regional stroke centre hub (38.9%).21 The results showed that mortality, sICH and functional outcomes were similar between the spoke and hub hospitals.21 In the Finnish Telestroke pilot study, patients treated with IV thrombolysis through teleconsultation had similar outcomes to those treated at the hub hospital (modified Rankin Scale (mRS) ≤2: 49.1% vs 58.1%; p=0.214).22 Besides being safe and reliable, a telestroke service may increase the rate of IV thrombolysis and improve stroke therapy in underserved areas.16 LaMonte et al23 reported that telemedicine significantly shortened the time to treatment compared with traditional service delivery (17 vs 33 min; p=0.003) and increased the use of rt-PA at a remote hospital from 5% to 24%. Pedragosa et al24 also found that the rate of IV rt-PA use was doubled (4.5% vs 9.6%) after a telestroke system was established in a community hospital. In Asia, Dharmasaroja et al25 also demonstrated the superiority of a telestroke service to traditional stroke care delivery, despite the differences in healthcare networks and resources between North America/Europe and Asia.

However, the effectiveness and reliability of a telemedicine consultation system for stroke patients in China are still unclear. This study is therefore designed to evaluate the performance of a telemedicine system in non-specialised hospitals providing on-site stroke therapy.

Methods and analysis

Objectives

The aim of the Acute Stroke Advancing Program using Telemedicine (ASAP-Tel) study is to evaluate the effectiveness and safety profile of a telemedicine consultation system in making decisions concerning IV thrombolysis. Specifically, the study aims to test whether implementation of the proposed programme can significantly increase the percentage of patients treated with IV thrombolysis as well as improve clinical outcomes (listed in the ‘Outcome measures’ section) for acute ischaemic stroke patients in underserved areas of China.

Study design

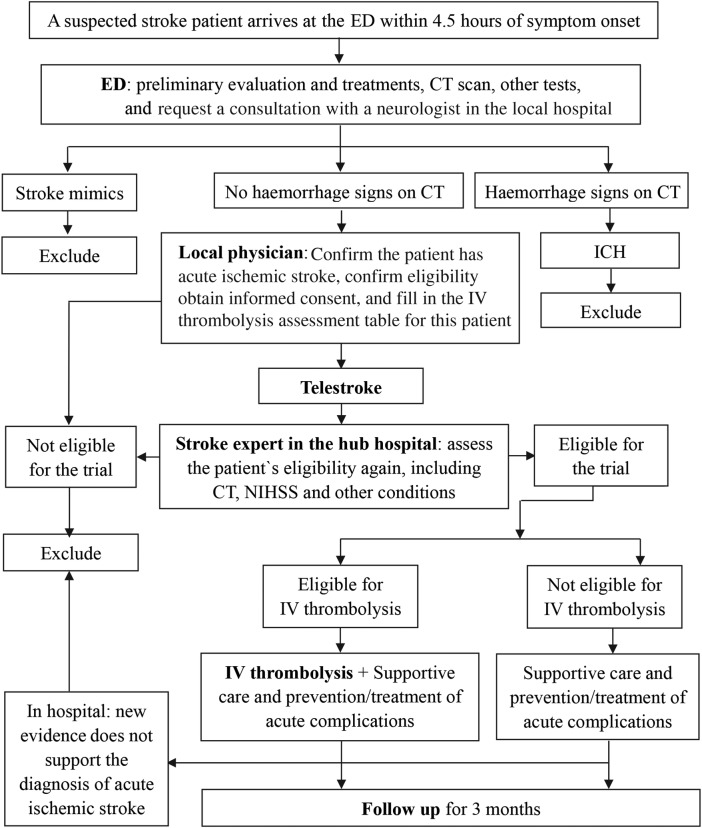

ASAP-Tel is a multicentre, historically controlled, superiority-designed study which will be conducted in underserved regions in China. The superiority design has been adopted because there is plenty of evidence showing the effectiveness of telestroke services and fewer participants will be needed to demonstrate efficacy using a single-sided test. This study's telestroke network consists of one hub hospital (Xijing Hospital, a comprehensive stroke centre, located in Xi'an) and 14 spoke hospitals (primary stroke centres in county-level hospitals in Yulin, located about 600 km from the hub hospital) in Shaanxi Province. Data on the usual stroke care quality of the spoke hospitals without guidance from the hub hospital prospectively collected over 1 year will be used as the historical control for the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants, outcome measures and data collection in the control group are the same as those in the teleconsultation group. The teleconsultation system will be introduced next year and the teleconsultation group recruited (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design for the Acute Stroke Advancing Program using Telemedicine (ASAP-Tel) and participant flow through the study. ED, emergency department; ICH, intracranial haemorrhage; IV, intravenous.

Eligibility

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants in the ASAP-Tel study are given below.

Inclusion criteria

Patients between 18 and 80 years of age

Acute ischaemic stroke

Presenting to the ED of spoke hospitals within 4.5 h of stroke symptom onset

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score between 4 and 25

Consent form signed by the participant or his/her authorised surrogate

Exclusion criteria

Time of symptom onset unclear

Unlikely to complete the study through a 3-month follow-up.

These criteria were selected in order to recruit as many ischaemic stroke patients as possible arriving in hospitals within 4.5 h of symptom onset. Patients whose NIHSS score is below 4 or above 25 will not be included as it is still unclear whether or not IV thrombolysis should be provided for such patients.

The diagnosis of acute ischaemic stroke will be made according to the 2010 Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke.7 Stroke aetiology classification will be collected for all participants and based on the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria.26

Recruitment and screening

Table 1 summarises the schedule of study activities and the variables to be measured at patient visits. Participants will be recruited from the 14 spoke hospitals in Yulin in Shaanxi Province. These hospitals were selected mainly because stroke patients in Yulin are always transported first to these centres, because they lack thrombolytic therapy specialists, and because their infrastructures are capable of facilitating the administration of IV thrombolysis with the help of experts in the hub hospital. All these hospitals are equipped with CT scanners, can perform the necessary laboratory tests, and can administer primary emergency treatment for stroke patients with severe complications.

Table 1.

Schedule of study activities by visit

| Activity | Recruitment/ screening | Decision-making concerning IV thrombolysis | 24 h±3 h | 7 days ±1 day | At discharge | 1 month ±3 days | 3 months ±7 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolment | |||||||

| Written informed consent | X | ||||||

| Contact information | X | ||||||

| Patient history | X | X | |||||

| Time intervals* | X | X | |||||

| Physical examination | X | ||||||

| NIHSS | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Blood pressure | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| CT scan | X | X | |||||

| Blood glucose | X | X | |||||

| Other laboratory tests | X | ||||||

| Confirm eligibility | X | ||||||

| Interventions | |||||||

| IV thrombolysis | Eligible patients | ||||||

| Supportive care | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Prevention/treatment of acute complications | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Assessments | |||||||

| Stroke complications | X | X | X | ||||

| New cardiovascular events | X | X | X | ||||

| Length of hospitalisation | X | ||||||

| mRS | X | X | X | X | |||

| Death | X | X | X | X | |||

*Time intervals include that from stroke onset to arrival in the ED, and from arrival in the ED to physician/CT initiation/CT interpretation/specific treatment.

ED, emergency department; IV, intravenous; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

When a suspected stroke patient arrives at the ED of a participating hospital, the emergency physician will immediately enquire about the patient's history, particularly the time of symptom onset, and swiftly examine the patient. It is important that the physician consults with a neurological physician in the local hospital. Several tests shall be emergently performed simultaneously to exclude important alternative diagnoses, assess for stroke complications and aid treatment selection, and will include non-contrast brain CT scan, blood glucose, oxygen saturation, serum electrolytes/renal function tests, complete blood count, markers of cardiac ischaemia, prothrombin time, international normalised ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time and electrocardiogram. Other tests, such as liver function tests, will be performed depending on the patient's condition. The neurological physician will then conduct further examinations and assess the patient for eligibility for the study. If the patient fulfils the study's eligibility criteria and signs the consent form, then he/she will be included tentatively. The physician will then, via the telemedicine consultation system, call a stroke expert in the hub hospital who will ensure the correct diagnosis of acute ischaemic stroke has been made and will assess the patient's eligibility a second time. The patient will be excluded if the expert considers that he/she does not meet the criteria used by researchers in all 14 Yulin hospitals. During hospitalisation, the patient may be excluded if new evidence that does not support the diagnosis of acute ischaemic stroke emerges (figure 1).

Telemedicine consultation system

The telemedicine consultation system is an interactive, two-way, wireless, audiovisual system using portable devices (iOS or Android tablet computers or smartphones) and developed by the School of Biomedical Engineering, the Fourth Military Medical University. The main application interface is a concise table for evaluating the criteria for IV thrombolysis and based on the 2013 American Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke.5 Photographs of CT films, other tests and real-time videos of patients can be linked to this interface. The use of tablet computers or smartphones allows improved and more convenient telecommunication between physicians in spoke hospitals and experts in hub hospitals compared to traditional teleconsultation systems.

A total of 10 certified stroke experts in the department of neurology in the hub hospital will provide teleconsultations 24 h per day, 7 days per week. During the teleconsultation, the experts will assess the patient's condition once again. On their tablet computers or smartphones, the experts can read the table, CT films and test results, and consider the NIHSS score and the condition of the patient in the local hospital via the interactive real-time video. Eligible patients will be quickly transported to the stroke unit, and the experts will decide if they are suitable for IV thrombolysis, and make other recommendations for treatment.

The protection of participants’ confidential information is very important. The following security procedures are part of the system: (1) a stable commercial server is equipped with security software; (2) the background database uses the AES encryption algorithm and will be saved and cleaned regularly; (3) and character and graphical passwords are needed for login and must be replaced regularly.

IV thrombolysis

In both groups of participants, those eligible for IV thrombolysis may decide which thrombolytic drug (rt-PA or urokinase) they will receive. IV rt-PA thrombolysis shall be administered within 4.5 h after symptom onset, at a dose of 0.9 mg/kg body weight (maximum, 90 mg), with 10% of the dose given as a bolus over 1 min and the remaining 90% infused over 60 min. The standard dose of IV urokinase is 1–1.5 million IU infused over a 30 min period; its administration will also be restricted to within 4.5 h of stroke onset instead of the 6 h adopted in other studies. The medications can be infused before admission to the stroke unit. If the patient develops severe headache, nausea, vomiting or acute hypertension or has worsening neurological function, the infusion shall be discontinued and an emergent CT scan, routine blood test and coagulation tests will be performed. In the teleconsultation group, patients treated with IV thrombolysis will receive all stroke care at the spoke hospitals. If the patient's condition deteriorates, the local physician may ask for a teleconsultation with the expert in the hub hospital, and the patient may be transported to the nearest comprehensive stroke centre if necessary.

Patients ineligible for IV thrombolysis will receive standard medical treatment; intra-arterial treatment will not be provided as these spoke hospitals are primary stroke centres and not qualified to carry out intra-arterial treatment.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

The study's primary outcome measure is the percentage of patients treated with IV thrombolysis within 4.5 h of stroke onset. This outcome is widely used in telestroke studies to reflect the effectiveness of direction from a specialised hospital via a telemedicine consultation system.15 19 22 23 It is measured as the rate of IV fibrinolytic drug (rt-PA or urokinase) administration among all included stroke patients.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures include: (1) the proportion of patients with a favourite outcome (mRS ≤2) at 1 month and at 3 months after stroke onset; (2) stroke complications within 24 h and within 7 days, including sICH, symptomatic cerebral oedema from an original brain infarction, cerebral hernia, seizure, severe extracranial bleeding, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary oedema, deep venous thrombosis and sepsis; (3) fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events within 7 days, including recurrent ischaemic stroke, ICH, subarachnoid haemorrhage, transient ischaemic attack, myocardial infarction, angina and heart failure; (4) all-cause mortality at 3 months; (5) time intervals from stroke onset to arriving in the ED, and from arriving in the ED to physician/CT initiation/CT interpretation/specific treatment; and (6) length of hospitalisation.

The best outcome is considered to be mRS ≤2 at 1 month (±3 days) and at 3 months (±7 days) after stroke onset. The mRS ranges from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating more severe disability and worse functional status after stroke (a score of 0 indicates no symptoms, a score of 5 indicates severe disability and bedridden, and a score of 6 indicates death).27

Stroke complications will be measured within 24 h (±3 h) of decision-making concerning IV thrombolysis and at 7 days (±1 day) following stroke onset. Symptomatic complications are defined as the presence of neurological deterioration with an increase of ≥4 points in the NIHSS score. Fatal and non-fatal recurrent ischaemic stroke and other cardiovascular events will also be recorded within 7 days (±1 day). A fatal event is one that is the immediate cause of someone's death. Every death and its time and cause will be recorded within 3 months after stroke onset. These outcomes will be used to determine the safety of the intervention.

Some valuable time points will be recorded to assess the reasons for pre-hospital and in-hospital delay in administering stroke care, including the time of symptom onset, time of arrival in the ED, time of emergency physician contact, time of CT initiation, time of CT interpretation and time of initiation of special treatment. These time intervals will be calculated. The length of hospitalisation is measured as the time from arrival in the ED to discharge.

Other measures

The NIHSS is a 15-item scale that rates the level of neurological impairment and ranges from 0 (no deficit) to 42 points (maximum possible deficits).28 The NIHSS will be measured in order to evaluate the neurological function of the patient at the time of arrival in the ED, at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 7 days after symptom onset, and if there is neurological decline.

A non-contrast CT scan will be performed at the time of arrival in the ED, at 24 h (±3 h) after IV thrombolysis, and if there is neurological decline. The Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) will be used to rate early ischaemic changes on CT.29 Fourteen regions of the brain are assessed in ASPECTS, the top 10 of which are in middle cerebral artery territory, with a score of 1 indicating a normal region and 0 indicating an ischaemic region. An ASPECTS score of more than 7 may correlate with good clinical outcomes in the future.30

Blood pressure (BP) will be measured in all included patients in the right arm using standard mercury sphygmomanometers in a supine position. Clinical personnel in the local hospitals have been trained to use the same method. BP will be measured at the time of arrival in the ED and every 2 h for 24 h, then every 4 h until 72 h after stroke onset.

Regimen for patients receiving IV thrombolysis

Patients receiving IV thrombolysis will be admitted to the stroke unit for monitoring. Neurological function and BP monitoring are essential and are both carried out every 15 min during and after IV rt-PA/urokinase infusion for 2 h, then every 30 min for 6 h, and then hourly until 24 h after IV thrombolysis.5 BP will also be measured with an electrocardiogram monitor in these patients. If systolic BP is >180 mm Hg or diastolic BP is >105 mm Hg, the frequency of BP measurements will be increased and antihypertensive medication to maintain BP at or below these levels will be administered.

Sample size and power calculation

Results of investigation in the participating hospitals before the present study indicated that the rate of IV thrombolysis within 4.5 h was about 2%. We have 90% power to detect a 6% increase in the percentage of ischaemic stroke patients treated with IV thrombolysis using a single-sided α of 0.05. Based on the formula estimating sample size for a superiority study and the above considerations, we estimate baseline and 3-month data from 226 participants in each group will be required. Assuming a 10% attrition rate, we plan to recruit 300 ischaemic stroke patients in each group.

Data collection

Before recruitment, physicians and nurses in the ED and the department of neurology of the participating hospitals will be trained in the protocol of this study, methods for operating the telemedicine consultation system, standards for filling in the case report form (CRF) and clinical guidelines for stroke management by experts from the hub hospital. Trained clinical personnel in the local hospitals will collect data using standard procedures to assess a stroke participant's baseline characteristics and track changes in patient condition during the study. Demographic information and anamnesis (history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, infection, wounds, drug use) will also be collected. All data are required to be recorded immediately after patient assessment unless an urgent procedure takes priority. All sites will use the same CRF.

At discharge, participants will be asked to return to the same hospital to undergo examination at 1 month (±3 days) and 3 months (±7 days) after stroke onset (table 1). If some participants are unable to attend, we will evaluate their mRS score via the telephone. To promote participant retention and complete follow-up, we will contact participants to ask about their condition and treatments received in other hospitals (if applicable) every 2 weeks after discharge. If we are unable to contact the participant, we will try to contact his/her relatives or neighbours to capture as much information as possible.

Data management

Every hospital and every participant will be allocated a unique identification number in this study. The paper CRFs will be filled in by researchers in the local hospital and the originals will be delivered to the hub hospital every quarter. Two data entry clerks in the hub hospital will independently enter the data into the computer from the CRFs and then validate the data with each other using EpiData V.3.1 software. The CRFs will be then stored in a special cabinet for inspection, and a dedicated person will be assigned to manage them.

Data analysis

Intention-to-treat analyses will be used throughout the study. The primary outcome will be compared between the two groups using the Pearson χ2 test in 2×2 table data. Time intervals and length of hospitalisation will be analysed using the t test. The rates of favourable outcome (mRS ≤2) and other outcomes will be compared using a logistic regression model. HRs between groups will be obtained with 95% CIs. Prespecified covariates forced into the models will include age, sex, centre and baseline NIHSS score, followed by other baseline covariates significantly (p<0.05) related to the rate of outcome events between the two groups. Interactions between these factors will also be explored. Subgroup analysis will be performed according to the results of interactive tests and clinical requirements, for example, in those patients who received rt-PA and those who received urokinase, and in those with different stroke aetiology classifications. All analyses will be performed with SPSS V.13.0 and R V.2.12.0.

Data and safety monitoring

An independent data and safety monitoring committee (DSMC) consisting of emergency medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, biostatistics and epidemiology experts has been established. The DSMC will review the quarterly reports on recruitment, participant retention, study safety and data quality, and monitor study progress. When severe adverse events occur, the experts in the hub hospital will help to evaluate and discuss the patient's condition and provide timely recommendations for treatment via the telemedicine consultation system.

Auditing

Two inspectors assigned by the hub hospital will occasionally visit the participating hospitals to supervise implementation of the study, check the quality of data, and correct non-standard practices. If 20% of CRFs at a site are substandard, then the site will be closed.

Ethics and dissemination

The procedures followed will be in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Xijing Hospital and with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from the IRB of Xijing Hospital on 23 May 2014 (approval number: KY20140523-1). At recruitment, every participant will be informed of the protocol of the study, and then he/she or his/her authorised surrogate will be asked to sign the consent form. The IRB will review the annual reports monitoring study progress.

The results will be presented at relevant conferences, published in scientific journals, and presented to local government and institutes supporting the introduction of telemedicine systems.

Discussion

ASAP-Tel is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of decision-making concerning IV thrombolysis via a telemedicine consultation system for acute ischaemic stroke patients in China. It differs from most foreign telestroke studies in that it is based on widely used, easily portable devices which can show real-time video. In 2011, Mitchell et al31 demonstrated the accuracy of a smartphone client–server teleradiology system, and showed that it could be used for the diagnosis of acute stroke. Demaerschalk et al32 indicated that a real-time video smartphone for assessing NIHSS score in acute stroke patients was reliable and accessible compared with bedside assessment. Here we have introduced a smartphone or tablet computer into telemedicine decision-making concerning IV thrombolysis for ischaemicstroke patients. We believe the portability and accessibility of this system will facilitate urgent management decisions in acute stroke. In addition, with the advent of fourth-generation telecommunications, mobile teleconsultation will be faster and of higher quality.

The main limitation of this study is that it is a historically controlled study, which may introduce some bias. However, we predict that any bias will not significantly influence the accuracy of results because the study period is short (2 years). The preliminary investigation found that the annual rates of IV thrombolysis were similar in recent years.

In conclusion, ASAP-Tel is designed to improve stroke care quality in local hospitals lacking neurological expertise. The telemedicine consultation system may play an important role in clinical practice for stroke patients, and may be extended to manage patients in broader settings in future.

Study status

This study is recruiting participants.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all site primary investigators, researchers and support staff in each participating hospital. We thank Xuedong Liu, Guodong Feng, Fang Yang and Ming Shi for providing valuable advice concerning study design and for revising the language of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to study design, and writing and revising the protocol. ZY, BW, ZL and GZ made substantial contributions to the original concept and study design, ZY, JW and JZ drafted the initial manuscript, and BW, ZL, GZ, FL and EL revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology of Shaanxi Province in China (a government organisation), grant number 2014KTCQ03-06. The funding body does not play any role in design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in the writing and publication of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of Xijing Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C et al. . Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet 2004;363:768–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E et al. . Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1317–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lansberg MG, Schrooten M, Bluhmki E et al. . Treatment time-specific number needed to treat estimates for tissue plasminogen activator therapy in acute stroke based on shifts over the entire range of the modified Rankin Scale. Stroke 2009;40:2079–84. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandercock P, Wardlaw JM, Lindley RI et al. . The benefits and harms of intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke (the third international stroke trial [IST-3]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:2352–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60768-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HJ et al. . Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013;44:870–947. 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1581–7. 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu M, Zhang S, Rao M et al. . 2010 Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Chin J Front Med Sci 2010;2:50–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Ninth 5-year National Project Collaboration. Intravenous thrombolysis with urokinase for acute cerebral infarctions (within 6 h from symptom onset). J Apoplexy Nerv Dis 2001;18:259–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Ninth 5-year National Project Collaboration. Intravenous thrombolysis with urokinase for acute cerebral infarctions (within 6 h from symptom onset). Chin J Neurol 2002;4:210–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bi Q, Zhang Z, Zhang WW et al. . Study on prehospital time and influencing factors of stroke patients in 15 Chinese cities. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2006;27:996–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Liao X, Zhao X et al. . Using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator to treat acute ischemic stroke in China: analysis of the results from the Chinese National Stroke Registry (CNSR). Stroke 2011;42:1658–64. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Wu D, Zhao X et al. . Hospital resources for urokinase/recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy for acute stroke in Beijing. Surg Neurol 2009;72(Suppl 1):S2–7. 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess DC, Audebert HJ. The history and future of telestroke. Nat Rev Neurol 2013;9:340–50. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva GS, Farrell S, Shandra E et al. . The status of telestroke in the United States: a survey of currently active stroke telemedicine programs. Stroke 2012;43:2078–85. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.645861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalouhi N, Dressler JA, Kunkel ES et al. . Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator administration in community hospitals facilitated by telestroke service. Neurosurgery 2013;73:667–71, 671–2 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller-Barna P, Schwamm LH, Haberl RL. Telestroke increases use of acute stroke therapy. Curr Opin Neurol 2012;25:5–10. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834d5fe4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Audebert H. Telestroke: effective networking. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:279–82. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70378-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Audebert HJ, Boy S, Jankovits R et al. . Is mobile teleconsulting equivalent to hospital-based telestroke services? Stroke 2008;39:3427–30. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.520478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Audebert HJ, Kukla C, Vatankhah B et al. . Comparison of tissue plasminogen activator administration management between Telestroke Network hospitals and academic stroke centers: the Telemedical Pilot Project for Integrative Stroke Care in Bavaria/Germany. Stroke 2006;37:1822–7. 10.1161/01.STR.0000226741.20629.b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Audebert HJ, Kukla C, Clarmann VCS et al. . Telemedicine for safe and extended use of thrombolysis in stroke: the Telemedic Pilot Project for Integrative Stroke Care (TEMPiS) in Bavaria. Stroke 2005;36:287–91. 10.1161/01.STR.0000153015.57892.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pervez MA, Silva G, Masrur S et al. . Remote supervision of IV-tPA for acute ischemic stroke by telemedicine or telephone before transfer to a regional stroke center is feasible and safe. Stroke 2010;41:e18–24. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.560169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sairanen T, Soinila S, Nikkanen M et al. . Two years of Finnish Telestroke: thrombolysis at spokes equal to that at the hub. Neurology 2011;76:1145–52. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318212a8d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaMonte MP, Bahouth MN, Xiao Y et al. . Outcomes from a comprehensive stroke telemedicine program. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:339–44. 10.1089/tmj.2007.0062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedragosa A, Alvarez-Sabin J, Molina CA et al. . Impact of a telemedicine system on acute stroke care in a community hospital. J Telemed Telecare 2009;15:260–3. 10.1258/jtt.2009.090102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dharmasaroja PA, Muengtaweepongsa S, Kommarkg U. Implementation of telemedicine and stroke network in thrombolytic administration: comparison between walk-in and referred patients. Neurocrit Care 2010;13:62–6. 10.1007/s12028-010-9360-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein LB, Jones MR, Matchar DB et al. . Improving the reliability of stroke subgroup classification using the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria. Stroke 2001;32:1091–8. 10.1161/01.STR.32.5.1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC et al. . Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988;19:604–7. 10.1161/01.STR.19.5.604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brott T, Adams HJ, Olinger CP et al. . Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989;20:864–70. 10.1161/01.STR.20.7.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang J et al. . Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome of hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. ASPECTS Study Group. Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score. Lancet 2000;355:1670–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02237-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tei H, Uchiyama S, Usui T. Predictors of good prognosis in total anterior circulation infarction within 6 h after onset under conventional therapy. Acta Neurol Scand 2006;113:301–6. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell JR, Sharma P, Modi J et al. . A smartphone client-server teleradiology system for primary diagnosis of acute stroke. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e31 10.2196/jmir.1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demaerschalk BM, Vegunta S, Vargas BB et al. . Reliability of real-time video smartphone for assessing National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores in acute stroke patients. Stroke 2012;43:3271–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.669150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]