Abstract

Objective

This study explores participants’ experience of self-management of dizziness using booklet-based vestibular rehabilitation (VR), with or without expert telephone support.

Design

Semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted.

Setting

Participants were recruited from primary care practices as part of a large RCT.

Participants

Interviews were carried out with 33 people (10 men and 23 women; age 27–84) self-managing chronic dizziness using booklet-based vestibular rehabilitation, with or without expert telephone support.

Results

Data were analysed using inductive thematic analysis. The majority of participants in both groups reported a positive experience of VR therapy, with many participants reporting an improvement in their dizziness symptoms since undertaking the therapy. Participants in the telephone support group felt that a genuine relationship developed between them and their therapist within three short sessions, and described their therapy sessions as reassuring, encouraging and motivational.

Conclusions

The VR treatment booklet appears to be a valued tool for self-managing chronic dizziness and people appreciate receiving remote telephone support.

Trial registration number

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Thematic analysis is a rigorous systematic approach to qualitative analysis.

Recruitment continued until the data reached saturation.

This study was nested within a randomised controlled trial and explores patient experiences of the therapy.

The sample inevitably comprises only of those people willing to be interviewed and it is, therefore, possible that those who appreciated the therapy may be over-represented.

Introduction

Chronic dizziness is a commonly experienced symptom and is believed to affect up to 25% of the community.1 Suffering from chronic dizziness can be debilitating and lead to loss of independence, reduced fitness, falls and fear of falling.2 Qualitative studies have highlighted the impact of dizziness on everyday life, often leading to poor function and disability.3 4 Dizziness is more common in older people, but it is estimated that 1 in 10 working-age adults suffer some degree of disability due to dizziness.5 Significant disability, medication use and medical consultations due to dizziness have been found in more than 20% of people over the age of 60,6 with 24% of dizziness being attributed to vestibular disorder.7

The vast majority of people suffering from dizziness consult their general practitioner (GP) in the first instance.7 It is estimated that 2% of all primary care consultations are for dizziness,6 8 with this figure increasing to as high as 30% in people over 65 years of age.9 The majority of patients experiencing dizziness symptoms have peripheral vestibular disorder (including benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), vestibular neuritis and Ménière's disease); serious sinister pathology in patients with no other symptoms is rare.10–12

Primary care patients with dizziness are typically treated and managed with reassurance and medication to relieve their symptoms.13 14 Reviews of the management of chronic dizziness have, however, concluded that no medication has well-established efficacy in the treatment of dizziness nor is any medication suitable for long-term use.11 15 Furthermore, many patients with chronic dizziness have unmet healthcare needs.3 Vestibular rehabilitation (VR) is now the recommended treatment for dizziness.15 16 The central component of VR is a programme of graded exercises consisting of eye, head and body movements designed to stimulate the vestibular system and promote neurological adaptation.14 VR exercises typically induce dizziness symptoms to start with, but repetition for several weeks generally results in partial or complete resolution of symptoms.17 18 However, only a few patients with chronic dizziness currently have access to VR therapy as referral to specialist clinics, where VR is typically delivered, can be lengthy and expensive.19 20

Yardley et al21 developed a booklet teaching home-based VR exercises for the self-management of dizziness. The booklet was designed to promote adherence to VR, and address cognitive and behavioural factors that may contribute to the high rates of psychological problems known to commonly accompany vestibular dysfunction22. VR elements of the treatment booklet is discussed in the main trial paper.23 This booklet has been evaluated in several clinical trials and has been found to be a safe, effective and cost-effective treatment for dizziness.21 23 24

Study context

This study was nested within a VR trial of booklet-based self-management of dizziness by patients in primary care.23 VR trial participants were randomised to either a routine care group, booklet only group or booklet with telephone support group. The trial used the self-treatment VR booklet21 to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of two models of VR delivery for people with dizziness: booklet only and booklet with telephone support. Results from the trial found that both the booklet only and booklet with telephone support groups had significantly improved vertigo symptoms compared to the routine care group at 1 year follow-up. Both treatment models were also found to be highly cost-effective.23

Incorporating qualitative work in clinical trials is an important part of person-based intervention development25 as it helps in understanding participants’ experiences and acceptability of the therapy. In recent years there has been an increasing focus on the patient experience of treatments and management of audiological conditions,26 although no research to date has assessed participants’ experiences of self-management of dizziness. This study aims to understand participants’ experience of using booklet-based VR alone or with telephone support in order to improve understanding of the experience of these models of dizziness self-management.

Method

Study design

This study used qualitative, semistructured interviews to explore and understand participant experiences of dizziness self-management using booklet-based VR alone or with telephone support.

Telephone support

The telephone support consisted of three short sessions (one 30 min session followed by two 15 min sessions) that was delivered by audiological scientists who received standardised training in delivering the telephone therapy. A treatment manual was followed during the telephone sessions and focused on ensuring the VR programme was implemented appropriately. Therapists also elicited and addressed participant concerns and agreed on goals. Follow-up sessions primarily focused on encouraging adherence to the programme and discussing barriers to adherence.

Participants and sampling

Approval for this study was granted by the National Research Ethics Service. Participants were a subgroup of participants taking part in the previously mentioned VR trial of self-management of dizziness.23 Participants were invited to take part in the trial if they had a diagnosis or treatment for dizziness in the past 12 months. Eligibility of potential participants was assessed at baseline to ensure participants were currently experiencing dizziness symptoms. Information about this study was included in the information sheet participants received in their invitation pack to take part in the VR trial. Consent for this study was included on the VR trial consent form, and it was made clear that participation was voluntary and would not affect participation in the VR trial. Recruitment was managed by an independent administrator and interviewing took place within a couple of months of participating in the VR trial.

Initially, consecutive sampling of participants who completed VR therapy was used. Participants were also sampled towards the end of the trial after the therapists had become more experienced in delivering the treatment. Purposive sampling was used towards the end of recruitment to ensure adequate representation of male participants. Recruitment continued until the data reached saturation and no new codes emerged. The sample consisted of 10 men and 23 women between the ages of 27 and 84 (M=59.3, SD=14.27). Fifteen participants (6 men, 9 women) were in the booklet only condition group and 18 participants (4 men, 14 women) were in the booklet and telephone support condition group. Participants were invited onto the trial because they had a diagnosis of vestibular dizziness. Symptom severity was measured by the Vertigo Symptom Scale—Short Form27 as part of the VR trial. Ten participants had high symptom severity (2 booklet only; 8 booklet and telephone support), and 23 participants had low symptom severity (13 booklet only; 10 booklet and telephone support).

Procedure

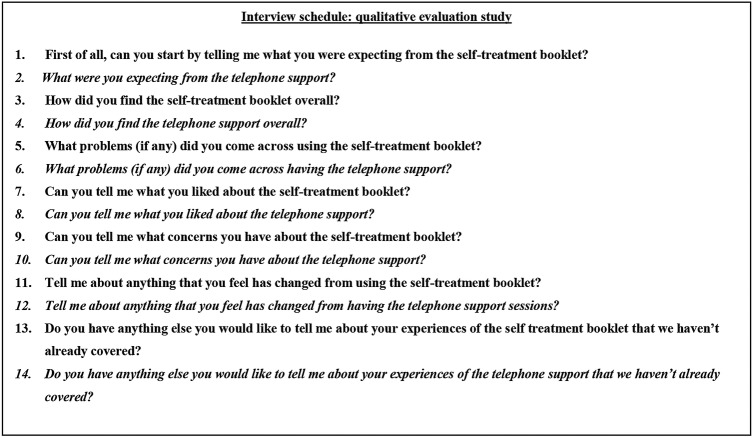

Semistructured telephone interviews were conducted between March 2010 and March 2011 by the first author (IM), and another female postgraduate health psychology trainee. Both researchers had limited knowledge of dizziness aetiology and treatments. The interview schedule is displayed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Semistructured interview schedule—italics indicating questions for participants from the telephone support group only.

Before starting the interview, the researcher spent a few minutes explaining that the study aimed to understand participants’ experiences of the treatment they received; it was emphasised that there were no right or wrong answers and that the interviewer was not involved in designing the clinical trial. It was hoped that this would minimise participants giving socially desirable responses such as being overly positive about their treatment.

The semistructured interview schedule included 14 broad, open-ended questions with follow-up prompts. Interviews began by asking participants what they expected from the VR trial and moved towards discussing participants’ experiences of the treatment. An inductive approach was taken, so that the interview schedule was used to guide, rather than dictate the interviews. The course of the interview was often tailored according to participants’ responses in an attempt to explore topics spontaneously raised by the participant. The interviews lasted between 9 and 47 min (M=18.27 min, SD=8.47). Interview transcripts were transcribed verbatim by an independent administrator.

Qualitative analysis

Analysis of interview transcripts was carried out by IM using an inductive thematic analysis where dominant themes were identified through close examination of the data.28 Interview recordings were listened to several times, and interview transcripts were read and re-read to ensure a high level of familiarity with the data.

First, open coding was carried out on 6 interview transcripts using maxQDA software and an initial coding schedule was devised in order to clearly define each emerging theme. The coding manual was then revised throughout the coding of the remaining transcripts. The original codes were frequently combined or divided into further codes depending on the emergent findings.28 Themes were continually compared with newly coded interview transcripts to ensure that these were readily applied to the data by using the researcher’s familiarity with the text and coding manual to frequently assess and reassess how codes were being applied to the raw data. The coding manual was discussed within the research team and final amendments were made. The final coding manual was then applied to all transcripts. The analysis process was carried out systematically, with category agreement being obtained at each stage of the analysis and inter-rater agreement between authors IM and SK obtained for the final coded data. To maintain anonymity, interview data were labelled by participant number, gender and treatment group (BO for booklet only and B+TS to indicate booklet with telephone support condition).

Results

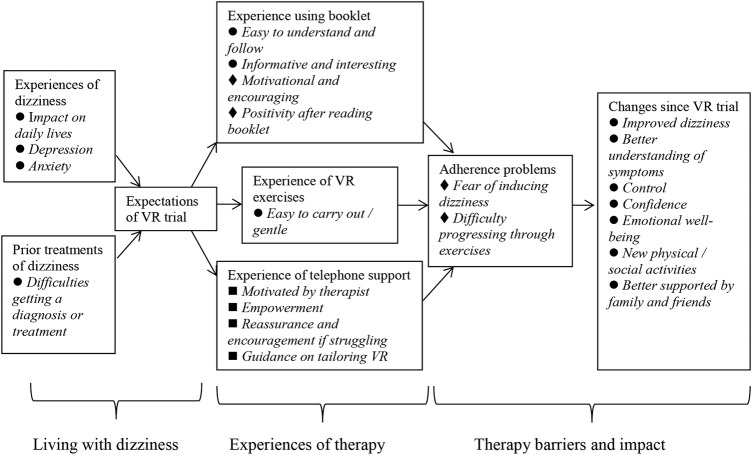

Analysis of 33 interview transcripts identified three main themes and eight subthemes. The themes, subthemes and key content are depicted in figure 2, highlighting the main group differences and similarities. The majority of the themes and subthemes arose from both groups (booklet only and booklet with telephone support), albeit in different contexts.

Figure 2.

Diagram of themes, subthemes and key content; •=Content from both treatment groups; ♦=Content mainly from booklet-only group; ▪=Content mainly from Booklet with telephone support group.

The identified themes can be organised into three main themes: (1) living with dizziness prior to the VR therapy; (2) experiences of therapy, and (3) therapy barriers and impact. Owing to the limited scope of this paper, the results will be presented in terms of these three themes. Supporting interview quotations are provided.

Living with dizziness prior to VR therapy

Experiences of dizziness

Participants were not explicitly asked about their experiences of living with dizziness, yet most participants spontaneously spoke about this during the interview. Several participants from both treatment groups described the practical ways in which their dizziness symptoms had affected their day-to-day lives. Dizziness was described as having major and often devastating consequences on participants’ lives in terms of disruption to daily tasks.

Participants also described the emotional impact suffering from dizziness had on them. Some talked about feeling depressed and ‘pulled down’ by their dizziness, while others mentioned feeling anxious and frightened by attacks of dizziness.

I can get up in the mornings and be fine and suddenly it might come on, and the minute it comes on I'm… it makes me feel miserable and depressed, you know. And I'm frightened how long it's going to last… I can't drive, I can't go to the shops, I've got to just wait and see how long. Sometimes I might have it a day; sometimes I might have it for weeks. So, yeah, it can really pull you down because you don't want to do anything, you don't want to bend over and do anything, you don't want to look up or you can't read a book, um watch telly, or do anything, knitting, computer work, you can't do anything, you've just got to sit and wait for it to sort itself out. So it really pulls you down. (26, female, BO)

Prior treatments of dizziness

Participants discussed prior medical treatments and consultations for dizziness. Many participants had encountered problems in gaining a diagnosis or treatment, with pharmacological treatments often described as ineffective.

I was glad to have it because I knew that there was something out there like this [VR exercises], but like I said I went to my doctor and got no joy from him about it… I had read things and it said there was nothing they could do, you know. The tablets don't really work when they give them to you. Just gave me a headache. (26, female, BO)

Some participants described their belief that there are no existing treatments for dizziness, while others spoke of how healthcare professionals had told them there were no available treatments and that they should learn to live with the condition.

When I went to the hospital… I'd felt a little bit, oh well that's it, you know, this is what's wrong and you're going to have to live with it, sort of thing, which is not a very caring feeling. (14, female, B+TS)

Experiences of therapy

Experience using booklet

The majority of participants described the VR booklet as being easy to understand and follow, with many describing the educational and informative nature of the booklet as helpful for increasing understanding of their condition.

I felt encouraged [through reading the booklet]. I thought, I've got to take this on and er.. keep going with it. (17, male, BO)

Experience of VR exercises

Participants found the exercise instructions clear, and were generally surprised by how gentle and easy it was to follow VR exercises.

Well, it was so easy to do. You know, there was nothing …nothing that I couldn't er.. do, or wouldn't do. (7, male, BO)

Participants in the telephone support condition discussed their experiences of doing the exercises after having a telephone support session. Participants described feeling encouraged to increase the intensity of the exercises and felt that the exercises were tailored to their individual needs following the telephone support session.

Well if she had gone through something with me then it would be a little bit more um.. refined to suit my particular needs, should I say. (14, female, B+TS)

Experience of telephone support

A large proportion of participants in the telephone support group mentioned their progress being monitored, and receiving advice and health information during the telephone session. Health information largely related to causes of dizziness and explanations of the way in which VR exercises retrain the balance system, which participants found helpful.

Several participants in the telephone support group thought that they would have benefited from extra telephone support sessions as they felt these had a motivational effect and helped them adhere to the exercises. Participants described feeling more focused and determined to follow the exercise regime properly following the support session.

I was finding that the problems that I experienced day to day were diminishing, and I guess there might have been a tendency not to sort of finish the thing properly, if I hadn't had the phone calls. (27, male, B+TS)

All participants in the telephone support condition discussed the relationship with their therapist. Participants described their therapists as being easy to talk to, which made them feel at ease, and that this contributed to their enjoyment of the telephone sessions.

I liked the manner of the people concerned and the fact that they didn't talk down. They weren't overly officious and medical in any way, so you didn't feel you were ..um.. talking to someone who knew a lot more then you did. But they put you at ease. It was very nice. (1, female, B+TS)

Having a good relationship with the therapist was discussed as a key element to feeling supported. One participant described how the extra support, encouragement and monitoring helped her adhere to the exercise programme just when she considered giving it up.

I think that just the fact that there was some support when I was sort of thinking, oh you know, I don't know if I want to do this. Just having somebody ring just to say you are doing really well, just carry on and I'll speak to you again in a couple of weeks. (20, female, B+TS)

Participants talked about feeling reassured, encouraged and empowered following their telephone session. Some participants discussed feeling as if their therapist genuinely cares about them and their well-being. Participants described their therapist being someone they could laugh with, someone who is willing to listen to them and understands their problems.

Well, yes it was quite nice. It was almost like a friend calling each time, you know, to see how I was getting on, and she was very pleased and I was very pleased. (14, female, B+TS)

Therapy barriers and impact

Adherence problems

Participants discussed factors affecting their adherence to the VR exercise programme. While some participants mentioned stopping the exercises early when their symptoms improved, the main reason participants gave for not adhering to the programme was that the exercises induced dizziness and often worsened their symptoms to start with. Some participants also mentioned difficulties increasing the intensity of the exercises. The vast majority of participants who reported adherence problems as a result of its inducing dizziness or after their symptoms improved were in the booklet only condition.

And maybe, maybe I'm just a bit of a wuss and I just gave up after 6–8 weeks. And maybe if I could keep going it would have helped me. I just, me personally, it was making me feel so nauseous for the rest of the day, I couldn't. And I did try the exercises at different times of day to see if I could work out a better time to do it, and that, you know, wasn't really any good. (5, female, BO)

Changes since VR trial

Changes since taking part in the VR trial were discussed by all participants. These included emotional, physical and social changes. Many participants felt that their dizziness symptoms had improved since undertaking the VR exercise programme; this included participants from both treatment groups.

Well, it's changed my life. I couldn't believe that such simple exercises could make such a difference to my balance, and the dizzy feeling, because I used to have them during the week, and I don't have them anymore. Having done the exercises, It doesn't happen. So.. you know, for me it's wonderful. (16, female, B+TS)

Many participants, from both treatment groups, described feeling more confident since following the VR exercise programme, especially in terms of doing physical or social activities they previously would have avoided.

I was going down the town on my own…I wasn't thinking ‘oh should I do that?’. Where now… I feel actually a little bit different, this might be really sad but I feel a bit different when I am walking. I feel as if my brain is in touch with my feet a little bit more. (28, female, BO)

Participants also discussed how the VR trial affected their emotional well-being. They mentioned feeling less stressed in their everyday lives, and this was linked to other health benefits such as suffering fewer headaches. Participants also reported feeling less anxious about their dizziness, attributing this to increased understanding about their condition. Participants described feeling less nervous of having a dizzy spell as they felt more capable of managing the symptoms. They also mentioned suffering less anxiety in their everyday lives as they now understood that it is not their behaviour that causes dizziness.

I'm not so frightened by it I suppose, actually in a way. Much calmer about the whole thing. (14, female, B+TS)

Participants from both treatment groups discussed how the trial helped them to realise that they are not alone in suffering from dizziness. Participants talked about the reassurance and confidence they got from realising that there are many other sufferers of dizziness. A couple of younger participants described the relief they felt when they realised it is not uncommon for people of their age to suffer from dizziness, despite the condition often being thought of as one only affecting older people. Participants also mentioned feeling reassured and comforted in the knowledge that there are researchers and healthcare professionals looking for more effective treatments for dizziness.

But to know that there are people out there trying to help us get rid of this gives you a boost, really gives you a boost, you know, you don't feel so alone, because there is nobody else around me that suffers with this. (26, female, BO)

Participants talked about feeling more supported by the people close to them, and believed this was a result of their loved ones having an increased awareness and understanding of dizziness after reading the trial materials. It was reported that this support and understanding gave participants more confidence in undertaking activities that they normally would have avoided.

So you know… things I would have avoided doing because I would have felt I'm going to fall over or something… I am not so risk adverse… I know I've got people that understand what I suffer from and are going to be able to help me and not allow me to fall,…. I don't tend to avoid doing some of the things that I think I would have done, because I would have been too afraid that I might have fallen over or something. I'm not allowing the dizziness to really impact you know, my quality of life and things that. (8, female, B+TS)

Discussion

This study aimed to understand participants’ experience of using booklet-based VR alone or with telephone support for dizziness self-management. The majority of participants reported a positive experience of VR therapy, whether it involved using the booklet alone or was accompanied by telephone support. Participants found the booklet easy to understand and follow, and were surprised by how simple and gentle the exercises were. Many participants also discussed improvements in their dizziness symptoms since following the VR exercise. Participants described feeling more confident, empowered, less anxious and more supported by family and friends. Participants also discussed partaking in social and physical activities that they could not previously do. These findings suggest booklet-based VR to be an acceptable and valued model for delivering VR.

Participants who received telephone support found the therapist's comments and suggestions reassuring, encouraging and motivational, and believed their therapist cared about them and their rehabilitation, which was regarded as a major element of feeling supported. Many participants felt that a genuine relationship developed between them and their therapist over the three sessions. This is consistent with previous therapeutic alliance research which suggests that the therapeutic relationship is established within the first three sessions.29 30 Similar findings were reported in a study evaluating patient-centred audiological rehabilitation in older adults with hearing aids.31 Patients identified a strong therapeutic relationship as the heart of their audiological rehabilitation and described trust, joint decision-making and the importance of being listened to as key factors in the maintenance of this relationship. A mixed-methods interaction analysis of the telephone support sessions for patients with chronic dizziness supported these findings by identifying patient-centred communication to be related to the therapeutic relationship.32

There were some indications that telephone support might encourage better adherence to the VR programme. Many participants described the support of their therapist and the positive attitude of their therapist towards their progress as being a key element in their perseverance with the exercises. Lack of adherence in the booklet only group was most commonly explained by fear of its inducing dizziness symptoms. In contrast to the booklet only group, participants who received the telephone support were given the opportunity to discuss their concerns with a VR therapist who was able to provide advice and allay fears that the exercises were damaging their balance system. The VR trial results23 found adherence to the full programme of exercises was reported by 44% of participants from the booklet with telephone support group compared to only 34% of participants in the booklet only group, although this group difference did not reach statistical significance. However, exploratory retrospective analyses found that participants from the telephone support group reported carrying out the exercises with greater intensity compared to the booklet only group.

Strengths and limitations

A limitation of this research is that the sample inevitably comprises only those people willing to be interviewed and is, therefore, likely to be non-representative of the trial population. In particular, those who appreciated the therapy and the telephone support may well be over-represented. However, several aspects of this research give confidence that the results reflect participants’ positive experiences of self-managing rehabilitation for chronic dizziness. Thematic analysis is a rigorous systematic approach to qualitative analysis and the inductive approach taken allows the findings of this study to be grounded in the data rather than being drawn from previous theories. The consecutive sampling methodology, managed by an independent administrator, allowed this study to include participants receiving telephone support from therapists at different stages in the RCT and therefore, varying degrees of experience in this particular setting. Recruitment continued until the data reached saturation, after which emerging theories were thoroughly explored through theoretical sampling, allowing for a varied sample to be included in this study. Interviewing took place within a couple of months of participants completing the 12-week treatment programme to ensure the experience of therapy was recent and fresh in the participants’ minds, a particularly important issue when dealing with elderly participants. While this approach was preferable, a longer delay between therapy and interviewing might have yielded an insight into long-term effects and lasting changes.

Clinical and research implications

Booklet-based VR has previously been found to be a cost-effective model of VR delivery,23 and the current findings suggest it to also be acceptable and valued by patients with chronic dizziness. Telephone support enhanced tailoring the VR therapy to the individual. Participants in the telephone support group felt that a genuine relationship developed between them and their therapist in three short sessions. This highlights the potential benefit that minimal remote contact can have on participants’ engagement in self-management programmes. The telephone-based method of delivering therapy did not appear to negatively impact the popularity of the treatment and may, in fact, be preferred by many patients with dizziness as previous research has found this patient group to be reluctant to travel for treatment.33 Telephone delivered therapy is a fast-growing, cost-effective method of delivering therapy and might be particularly beneficial for use in elderly or disabled patients.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Ingrid Muller at @IngridMuller7

Contributors: All authors were involved in the study design and analysis. The majority of interviews and initial coding of the data were conducted by IM. SK provided inter-rater agreement for all final coded data, and LY provided category agreement at each stage of data analysis. All authors were involved in the writing and preparation of this manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: NREC and University of Southampton REC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hannaford PC, Simpson JA, Bisset AF et al. The prevalence of ear, nose and throat problems in the community: results from a national cross-sectional postal survey in Scotland. Fam Pract 2005;22:227–33. 10.1093/fampra/cmi004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SM, Munoz B, West SK et al. Falls and fear of falling: which comes first? A longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies for primary and secondary prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1329–35. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50352.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsson Möller U, Hansson EE, Ekdahl C et al. Fighting for control in an unpredictable life-a qualitative study of older persons’ experiences of living with chronic dizziness. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:97 10.1186/1471-2318-14-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller M, Schuster E, Strobl R et al. Identification of aspects of functioning, disability and health relevant to patients experiencing vertigo: a qualitative study using the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:75 10.1186/1477-7525-10-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yardley L, Owen N, Nazareth I. Prevalence and presentation of dizziness in a general practice community sample of working age people. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1131–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sloane P, Blazer D, George LK. Dizziness in a community elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989;37:101–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb05867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M et al. Burden of dizziness and vertigo in the community. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:2118–24. 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroenke K. Symptoms in medical patients: an untended field. Am J Med 1992;92:S3–6. 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90129-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colledge NR, Wilson JA, Macintyre CC et al. The prevalence and characteristics of dizziness in an elderly community. Age Ageing 1994;23:117–20. 10.1093/ageing/23.2.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroenke K, Hoffman M, Einstadter D. How common are various causes of dizziness? A critical review. South Med J 2000;93:160–7; quiz 168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanley K, O'Dowd T, Considine N. A systematic review of vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51:666–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansson E, Månsson NO, Håkansson A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo among elderly patients in primary health care. Gerontology 2005;51:386–9. 10.1159/000088702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayarajan V, Rajenderkumar D. A survey of dizziness management in general practice. J Laryngol Otol 2003;117:599–604. 10.1258/002221503768199915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandt T. Management of vestibular disorders. J Neurol 2000;247:491–9. 10.1007/s004150070146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansson EE. Vestibular rehabilitation- for whom and how? A systematic review. Adv Physiother 2007;9:106–16. 10.1080/14038190701526564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wrisley DM, Pavlou M. Physical therapy for balance disorders. Neurol Clin 2005;23:855 10.1016/j.ncl.2005.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall CD, Cox LC. The role of vestibular rehabilitation in the balance disorder patient. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2009;42:161–9. 10.1016/j.otc.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillier SL, Hollohan V. Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD005397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polensek SH, Sterk CE, Tusa RJ. Screening for vestibular disorders: a study of clinicians’ compliance with recommended practices. Med Sci Monit 2008;14:CR238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fife D, Fitzgerald JE. Do patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo receive prompt treatment? Analysis of waiting times and human and financial costs associated with current practice. Int J Audiol 2005;44:50–7. 10.1080/14992020400022629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yardley L, Donovan-Hall M, Smith HE et al. Effectiveness of primary care-based vestibular rehabilitation for chronic dizziness. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:598–605. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yardley L. Overview of psychologic effects of chronic dizziness and balance disorders. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2000;33:603 10.1016/S0030-6665(05)70229-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yardley L, Barker F, Muller I et al. Clinical and cost effectiveness of booklet based vestibular rehabilitation for chronic dizziness in primary care: single blind, parallel group, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344:e2237 10.1136/bmj.e2237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yardley L, Kirby S. Evaluation of booklet-based self-management of symptoms in Meniere disease: a randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med 2006;68:762 10.1097/01.psy.0000232269.17906.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K et al. The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e30 10.2196/jmir.4055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knudsen LV, Laplante-Levesque A, Jones L et al. Conducting qualitative research in audiology: a tutorial. Int J Audiol 2012;51:83–92. 10.3109/14992027.2011.606283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yardley L, Masson E, Verschuur C et al. Symptoms, anxiety and handicap in dizzy patients: development of the vertigo symptom scale. J Psychosom Res 1992;36:731–41. 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90131-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joffe H, Yardley L. Content and thematic analysis. In: Marks D, Yardley L, eds. Research methods for clinical and health psychology. London: Sage, 2000:56–67.. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eaton TT, Abeles N, Gutfreund MJ. Therapeutic alliance and outcome—impact of treatment length and pretreatment symptomatology. Psychotherapy 1988;25:536–42. 10.1037/h0085379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horvath AO, Symonds BD. Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy—a metaanalysis. J Couns Psychol 1991;38:139–49. 10.1037/0022-0167.38.2.139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grenness C, Hickson L, Laplante-Levesque A et al. Patient-centred audiological rehabilitation: perspectives of older adults who own hearing aids. Int J Audiol 2014;53:S68–75. 10.3109/14992027.2013.866280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller I, Kirby S, Yardley L. The therapeutic relationship in telephone-delivered support for people undertaking rehabilitation: a mixed-methods interaction analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:1060–5. 10.3109/09638288.2014.955134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yardley L, Burgneay J, Andersson G et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of providing vestibular rehabilitation for dizzy patients in the community. Clin Otolaryngol 1998;23:442–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1998.00179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]