In spite of significant progress made in tuberculosis (TB) control, nine million people developed TB disease in 2013, and 1.5 million died of TB1. While implementation of the Stop TB (DOTS) Strategy has cured millions of patients with TB, and undoubtedly saved lives, the impact of this strategy on reducing TB incidence has been disappointing1. The TB epidemic is declining at the rate of 1.5 per cent per year, much slower than what mathematical models had predicted1. At the current rate of decline, TB elimination by 2050 is considered impossible.

DOTS, apparently, cures patients and saves lives, but it does not seem to be very effective in interrupting TB transmission. Under India's Revised National TB Control Programme (RNTCP) millions of TB patients have been treated, and countless lives have been saved2,3. But TB incidence in India continues to remain high3. Of the nine million TB cases in 2013, India alone accounted for 25 per cent of the cases. India also accounts for one of the three million ‘missing’ cases-patients with TB who are either not diagnosed, or not notified1,4.

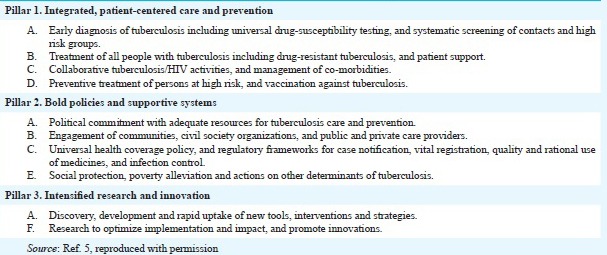

In 2014, the World Health Assembly endorsed a new, bold plan called “The End TB Strategy”5. The vision is “A world free of TB - Zero TB deaths, Zero TB disease, and Zero TB suffering”. The goal is to end the global TB epidemic (<10 cases per 100,000). Essential elements of the three pillars of this strategy are shown below.

How is the ‘End TB Strategy’ relevant in the Indian context, and how can India be a world leader in implementing the End TB Strategy?

Pillar 1: How can India improve patient-centered TB care and prevention?

India is doing a lot to improve the diagnosis of TB, and to move towards the goal of universal drug-susceptibility testing (DST). In 2012, based on a WHO policy, the Indian government banned the use of serological, antibody-based TB tests that were popular in the private market6. This bold step has been widely appreciated as an important move to prevent mismanagement of TB patients.

In the public sector, the RNTCP, in collaboration with partners such as Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) and WHO, has done several pivotal studies to evaluate new, WHO-endorsed TB diagnostics, including light-emitting diode (LED) fluorescence microscopy, liquid cultures, line probe assays (LPA), and Xpert MTB/RIF (GeneXpert)7,8,9,10. Based on this impressive evidence base, all of these new technologies have been included in the Programme, and are being gradually scaled-up3. RNTCP has established a network of over 60 laboratories to improve access to culture and DST3. But implementation of these tools in the public sector alone is unlikely to have a big impact11. This is because most TB patients seek care initially in the private and informal sector. Thus, it is important to make sure new tools are also affordable and accessible in the private sector.

The most important development in the private sector, has been the Initiative for Promoting Affordable and Quality TB Tests (IPAQT)12. This unique initiative, coordinated by the Clinton Health Access Initiative, has made WHO-endorsed TB tests (i.e. liquid cultures, LPA, and Xpert MTB/RIF) more affordable and accessible to patients in India, through a network of over 90 accredited private laboratories and hospitals. These laboratories and hospitals are offering TB tests at prices that are 30-50 per cent less than the market price. In addition, they are notifying confirmed TB cases to the RNTCP, and are actively educating private doctors about the value of quality-assured, WHO-endorsed TB diagnostics. Over 130,000 patients have benefitted from this initiative in less than two years12.

Box.

Three pillars of the End TB Strategy

According to WHO, with the roll-out of rapid molecular tests, there has been a three-fold increase in the number of multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB cases detected globally1. A similar phenomenon is occurring in India. Responding to the growing threat of drug-resistant TB, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) has rapidly scaled up access to GeneXpert technology, and this has resulted in the detection of MDR-TB in a large number of patients, who would have otherwise been missed13. In 2013, there was an 8-fold increase in patients accessing drug resistant TB treatment when compared to 201113. A recent study from Mumbai has underscored the importance of universal DST, and the need to provide customized treatment, based on DST results14.

Globally, the ‘Test and Treat’ strategy, where every TB patient is routinely offered a DST to guide choice of treatment regimen, is becoming the standard of care in many settings4,6,15, and is a key element of the first pillar of the End TB Strategy. India should aim to make universal DST accessible to all TB patients within the next 2-3 yr16. This will require India to not only scale-up access to rapid molecular tests and liquid cultures in the public sector, but also proactively work with private hospitals, private medical colleges, and laboratories to harness the laboratory capacity that exists in the private sector.

MDR-TB treatment is now more accessible via Programmatic Management of Drug-resistant TB (PMDT) centres in the public sector3. However, the need is much larger than what PMDT can currently offer; only about 20,000 patients were put on MDR-TB therapy in 20133. The RNTCP will need to invest more resources in the expansion of PMDT, to ensure that all MDR-TB patients in India get the appropriate care they deserve, and do not incur catastrophic health expenses. Recently, the Global Drug Facility (GDF) of the Stop TB Partnership announced that the price of cycloserine will be reduced by half in 2015 compared to the previous year17. Such global initiatives could be supplemented by local negotiations with Indian generic pharmaceutical companies to further reduce prices of second line drugs for Indian patients.

While preventive therapy for latent TB infection has not been a critical focus of RNTCP, this strategy could be considered for at least two highly vulnerable populations – people living with HIV/AIDS, and child contacts under the age of 5 yr18. Prevention of active TB in these populations will be highly impactful.

Pillar 2: How can India make and implement bold plans?

At a national level, India has made several ambitious and impressive policies and plans. These include the ban on serological tests, mandatory notification of all TB cases, the National Strategic Plan, and the TB Mission 2020 plan2,19. In 2014, the Standards for TB Care in India was published6. At the regional level, cities such as Mumbai have shown great leadership and commitment, by developing their own TB control plans, and working with a variety of national and international partners to raise funds, and mobilize communities. The Mumbai Mission for TB Control is an excellent example of what local leadership can achieve12. Progress has also been made in the engagement of the private sector to improve TB care and to make TB treatment more affordable to patients treated in the private sector20,21,22. Pilot projects in cities such as Mehsana, Mumbai, and Patna show that it is feasible to aggregate, educate and incentivize private providers, and to improve TB case notification, and quality of care22.

Social protection is a key component of the Pillar 2 of the End TB Strategy. Several studies from India have raised awareness about the importance of malnutrition as a potential driver of the TB epidemic in India23,24. The Indian government will need to seriously address the high levels of malnutrition in India as well as the inequity and poverty that underlie the problem. Programmes such as Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) should be harnessed to protect TB patients from catastrophic expenditures.

Despite ambitious plans, what is perhaps missing is the high level political commitment necessary to make sure that RNTCP is adequately funded, to fully implement the National Strategic Plan25. Advocacy is critical to raise awareness about TB at the national level.

Pillar 3: How can India intensify research and innovation?

Historically, India has made good contributions in TB research26, including large vaccine trials, randomized trials of short-course therapies, and operational research to improve programme efficiency. Indian companies and agencies have developed novel TB diagnostics and are actively engaged in TB drug discovery. These R&D initiatives in India deserve greater funding support from agencies such as the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), and Department of Science and Technology (DST).

While several new TB diagnostics (e.g. GeneXpert) and new drugs (e.g. bedaquiline and delamanid) have emerged in the recent past, their evaluation and adoption has been slow. A clear framework for evaluation and endorsement of new TB tools will be helpful, for product developers as well as implementers. Without a clear pathway for product validation and policy, the benefits of new TB technologies are unlikely to reach patients who need them the most. In this context, there is a great scope for national TB institutes (e.g. National Tuberculosis Institute, National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, National Institute of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases, and National JALMA Institute of Leprosy and other Mycobacterial Diseases) to play a key role as product evaluators who can conduct multicentric evaluation studies, and generate highquality evidence for policy making. These national TB institutes have a long and rich tradition of evaluating technologies (e.g. BCG) and strategies (e.g. daily versus intermittent drug regimens) in the past, and are well placed to take on this task.

Conclusion

India has made tangible progress in TB control, but much more work is needed to reach the goal of ending the TB epidemic in the country. But with high level leadership, political commitment, active engagement of both public and private sectors, and active support from civil society, celebrities, and philanthropists, India could blaze the trail for other high burden TB countries to emulate, and demonstrate that it is indeed possible to end the TB epidemic.

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis report 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. World Health Organization (WHO) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sachdeva KS, Kumar A, Dewan P, Kumar A, Satyanarayana S. New Vision for Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP): Universal access - “Reaching the un-reached”. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:690–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annual Status Report. New Delhi, India: Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2014. Central TB Division. TB India 2014. Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swaminathan S. Tuberculosis in India - can we ensure a test, treatment & cure for all? Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:333–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy. Global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015. [accessed on October 27, 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/post2015_TBstrategy.pdf?ua=12014 .

- 6.World Health Organization Country Office for India. Standards for TB Care in India. [accessed on February 25, 2015]. Available from: http://www.tbcindia.nic.in/pdfs/STCI%20Book_Final%20%20060514.pdf .

- 7.Reza LW, Satyanarayna S, Enarson DA, Kumar AM, Sagili K, Kumar S, et al. LED-fluorescence microscopy for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis under programmatic conditions in India. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raizada N, Sachdeva KS, Nair SA, Kulsange S, Gupta RS, Thakur R, et al. Enhancing TB case detection: experience in offering upfront Xpert MTB/RIF testing to pediatric presumptive TB and DR TB cases for early rapid diagnosis of drug sensitive and drug resistant TB. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raizada N, Sachdeva KS, Sreenivas A, Kulsange S, Gupta RS, Thakur R, et al. Catching the Missing Million: Experiences in enhancing TB & DR-TB detection by providing upfront Xpert MTB/RIF testing for people living with HIV in India. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raizada N, Sachdeva KS, Sreenivas A, Vadera B, Gupta RS, Parmar M, et al. Feasibility of decentralised deployment of Xpert MTB/RIF test at lower level of health system in India. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salje H, Andrews JR, Deo S, Satyanarayana S, Sun A, Pai M, et al. The importance of implementation strategy in scaling up Xpert MTB/RIF for diagnosis of tuberculosis in the Indian health-care system: A transmission model. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pai M. Promoting affordable and quality tuberculosis testing in India. J labor physicians. 2013;5:1–4. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.115895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai. Mumbai Mission for Tuberculosis (TB) Control, India. [accessed on February 25, 2015]. Available from: http://www.stoptb.org/news/stories/2014/ns14_084.asp2014 .

- 14.Dalal A, Pawaskar A, Das M, Desai R, Prabhudesai P, Chhajed P, et al. Resistance patterns among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Greater Metropolitan Mumbai: Trends over time. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.TB CARE I. International standards for tuberculosis care. 3rd ed. [accessed on February 25, 2015]. Available from: www.istcweb.org 2014 .

- 16.Jain Y. India should screen all tuberculosis patients for drug resistant disease at dignosis. BMJ. 2015;350:h1235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stop TB Partnership. stop TB Partnership7s Global Drug Facility (GDF) achieves historic price reduction for MDRTB drug Cycloserine. [accessed on February 25, 2015]. Available from: http://www.stoptb.org/news/announcements/2015/a15_006.asp .

- 18.Geneva: WHO; 2014. World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on the management of latent tuberculosis infection, WHO/HTM/TB/2015.01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagcchi S. Indian government outlines plan to try to eliminate tuberculosis by 2020. BMJ. 2014;349:g6604. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pai M, Dewan P. Testing and treating the missing millions with tuberculosis. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pai M, Yadav P, Anupindi R. Tuberculosis control needs a complete and patient-centric solution. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2:e189–e90. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewan P. How India is moving the needle on TB. [accessed on February 25, 2015]. Available from: http://www.impatientoptimists.org/Posts/2015/01/How-India-is-moving-the-needle-on-TB?utm_ .

- 23.Bhargava A, Sharma A, Oxlade O, Menzies D, Pai M. Undernutrition and the incidence of tuberculosis in India: national and subnational estimates of the population-attributable fraction related to undernutrition. Natl Med J India. 2014;27:128–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhargava A, Chatterjee M, Jain Y, Chatterjee B, Kataria R, Bhargava M, et al. Nutritional status of adult patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in rural central India and its association with mortality. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pai M. TB control requires new tools, policies, and delivery models. Indian J Tuberc. 2015;62:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Small PM, Katoch VM. India's contribution to global TB control: Innovative & integrated implementation research. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:267–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]