ABSTRACT

We searched The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database for viruses by comparing non-human reads present in transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) and whole-exome sequencing (WXS) data to viral sequence databases. Human papillomavirus 18 (HPV18) is an etiologic agent of cervical cancer, and as expected, we found robust expression of HPV18 genes in cervical cancer samples. In agreement with previous studies, we also found HPV18 transcripts in non-cervical cancer samples, including those from the colon, rectum, and normal kidney. However, in each of these cases, HPV18 gene expression was low, and single-nucleotide variants and positions of genomic alignments matched the integrated portion of HPV18 present in HeLa cells. Chimeric reads that match a known virus-cell junction of HPV18 integrated in HeLa cells were also present in some samples. We hypothesize that HPV18 sequences in these non-cervical samples are due to nucleic acid contamination from HeLa cells. This finding highlights the problems that contamination presents in computational virus detection pipelines.

IMPORTANCE Viruses associated with cancer can be detected by searching tumor sequence databases. Several studies involving searches of the TCGA database have reported the presence of HPV18, a known cause of cervical cancer, in a small number of additional cancers, including those of the rectum, kidney, and colon. We have determined that the sequences related to HPV18 in non-cervical samples are due to nucleic acid contamination from HeLa cells. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the misidentification of viruses in next-generation sequencing data of tumors due to contamination with a cancer cell line. These results raise awareness of the difficulty of accurately identifying viruses in human sequence databases.

INTRODUCTION

In 1951, a biopsy specimen was taken from a cervical adenocarcinoma of Henrietta Lacks. The first immortal human cancer cell line, called HeLa (1), was produced from this tissue. HeLa was the only human cancer cell line available at the time, and because of its growth potential, it was widely distributed to laboratories around the world. Subsequently, HeLa rapidly outgrew many cell lines (2, 3). Cross-contamination was even suspected from air droplets (4). Evidence of widespread contamination eventually turned into a controversy that is still unsettled today (5, 6). More than 50 years later, HeLa cell contamination is still being uncovered in cell lines (7) and the problem of cell line contamination is not limited to HeLa (8, 9).

Human papillomavirus 18 (HPV18) is integrated in the HeLa genome (10). Three segments of HPV18 are integrated at a known fragile site on chromosome 8 (locus 8q24) which is located approximately 500 kb upstream of the myc gene. The integrated portion of HPV18 includes genomic regions from bases 1 to 3088 and 5736 to 7857 (11) of the reference genome, and thus contains the long control region (LCR), the E6, E7, and E1 genes, and partial coding regions for the E2 and L1 genes. The E4, E5, and L2 genes are deleted. The integration causes a truncation in the E2 gene, a negative regulator of viral E6 and E7 expression (12), thereby allowing transcriptional activation of the E6 and E7 oncogenes. In addition, the integrated HPV18 sequence differs from the reference genome at 23 base positions (13).

Human papillomaviruses are found in almost every case of cervical cancer. HPV16 and HPV18 are the primary etiological agents, accounting for 70% of all cases (14, 15). High-risk HPV has also been detected in colorectal samples, but these findings remain controversial (16–18). Recently, HPV18 has been detected in colorectal samples and a normal kidney sample in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (19, 20). In these reports, the pattern of viral transcription is indicative of oncogenic integration. TCGA collates large-scale genome sequencing of thousands of tumor samples from more than 30 human cancers. This large pool of sequencing data has afforded an unprecedented opportunity for the research community to search for viruses in human tissue. We are searching the TCGA database for the presence of known and novel viruses. Here, we report on the authenticity of HPV18 sequences and the apparent HeLa cell contamination in some TCGA samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cancer databases.

The results published here are in whole based upon data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). All human data were handled in accordance with a Data Access Request between the University of Pittsburgh and the NIH for dbGaP study accession number phs000178. Selected transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) and whole-exome sequencing (WXS) BAM files were downloaded with GeneTorrent (http://cghub.ucsc.edu) and handled in accordance with the TCGA Data Use Certification Agreement (version 9/12/2013). BAM files are the binary format of the sequencing alignment map (SAM) format (http://samtools.github.io/hts-specs/SAMv1.pdf).

Computational pipeline for virus detection.

Non-human reads from TCGA BAM files were extracted and processed with prinseq-lite.pl (21) with the command line options “-lc_method entropy -lc_threshold 60 -min_qual_mean 15 -ns_max_p 5 -trim_qual_right 10 -trim_qual_left 10 -min_len 30” to trim and remove poor-quality sequences. High-quality reads were mapped to the Viral RefSeq (VRS) database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/release/viral/; downloaded December 2012) with Bowtie 2 (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml; 22). Bowtie 2 is a very fast aligner of short sequences (such as those generated in high-throughput sequencing) to long sequences, such as the human genome. VRS-mapped reads were additionally filtered by mapping them with Bowtie 2 to the human genome 19 (hg19) database. Finally, all hg19-unmapped reads were remapped to VRS with Bowtie 2 to create a set of raw virus alignments. All Bowtie 2 commands used default options except that the “--very-sensitive” option was used. HPV18 was considered detected in a TCGA BAM file if the number of alignments to the virus was ≥10.

Single-nucleotide variant analysis.

A list of 23 single-nucleotide variant (SNV) sites that differ between the HPV18 sequence found in HeLa cells (GenBank accession number U89349) and the HPV18 reference sequence was constructed. This list and virus alignments were input into a Perl script to tabulate various statistics on the number of alignments and SNVs detected relative to the HPV18 reference genome. Virus alignments (in BAM format) were visualized with IGV (23). IGV is a popular visualization tool for exploring high-throughput sequencing experiments. For the TCGA analysis identifiers used, see Table 2.

TABLE 2.

RNA-Seq analysis identifiers for samples in which HPV18 was detected

| Cancera | Analysis identifier |

|---|---|

| CESC | 03a10ee1-df38-4e0f-ae4e-7f6fcd1a1895 |

| CESC | 0a23eb58-675c-4064-8cb0-83c8614e6584 |

| CESC | 0a63d10f-6a94-48ac-9553-350e4348dae6 |

| CESC | 0a8974f6-fe03-46aa-80b6-51220336c2e1 |

| CESC | 0b27b7f2-6c60-4777-884a-d62537f81fa3 |

| CESC | 0f8cd902-1558-47bd-8cb2-56a9be91358c |

| CESC | 135a40a7-836b-4f3d-9952-53ca0beef8b1 |

| CESC | 1534d589-9d95-4abe-b8d3-db0cb9c5cce7 |

| CESC | 33131849-8cdc-4e12-a8fd-b076f549fe65 |

| CESC | 3e41fb8b-94cc-4007-8d94-77a17ebafaaf |

| CESC | 44e4a7b7-3714-4059-9be5-970330a61924 |

| CESC | 4652f607-0663-4174-b8df-b9a6fae6c5f5 |

| CESC | 515b1396-2130-44e4-9f5a-f28136f60c1f |

| CESC | 591321a0-9dd8-4830-a1fe-1384fd5206ec |

| CESC | 73d0b019-3fc8-4cf4-9b5c-1227137b8f7e |

| CESC | 7a53f5a3-5c8e-4166-8587-5935cea9fa42 |

| CESC | 7efc08d0-5617-49d0-9ae5-eb7be6f011ac |

| CESC | 86fa0743-1851-4a3f-98bc-912cd6f4c5f5 |

| CESC | 91c69984-7478-4f57-bdbc-3a9bbd3cc263 |

| CESC | 9ef6a362-2112-4ef2-a0aa-cb44d06e3b23 |

| CESC | a594c907-6b8a-4e1c-9809-40c7d7ef49b1 |

| CESC | acc8137b-470f-4250-9034-6bff2ce6701e |

| CESC | af0916c7-26fd-4221-925f-d7ab6182d9ac |

| CESC | b22e3b41-05f6-4314-8798-e296849747f9 |

| CESC | b74fa8d5-d7e3-4ff3-8910-fe21471a2123 |

| CESC | c303d60e-56b4-442b-8859-bfe9037bfece |

| CESC | c78d2edd-d291-4061-bada-656934037901 |

| CESC | d3f756b0-89ef-4855-a880-c549f3d29422 |

| CESC | de259f25-f66d-44b3-8de1-8d9197b51630 |

| CESC | e3138b8a-932f-417b-b17f-a9c632bd4842 |

| CESC | e66979d2-6c3f-43da-be05-aa4d60ba4f14 |

| CESC | f1a92d9f-c9dc-4936-98e5-9c2f18455919 |

| CESC | f33114a0-87fd-418d-af0a-d35342d158c5 |

| CESC | fcdc8d35-de1c-489f-96cb-3f5a8cd0273d |

| COAD | 12c5a403-16f8-4cd7-95e6-4f762dbf41a2 |

| COAD | 1745a5ba-1782-44f4-bb56-1e04600c98d9 |

| COAD | 30db7dfe-9080-43e4-8ca3-48b042696d9a |

| COAD | 37baf410-1557-4df0-a022-cf0c977f82b8 |

| COAD | 41ff3ea0-e0e5-460e-80d1-e155be76e17c |

| COAD | 47e2e8c7-856b-4386-b78b-def7cd04ee6f |

| COAD | 4f25c71c-425a-4874-bf51-cd5f9f0f8068 |

| COAD | 6428e5a9-337c-4d4b-a0bf-41af336217e1 |

| COAD | 6622d155-029a-4f67-8f48-79c06ac4439e |

| COAD | 6ebb879b-97d5-47b5-9b21-4132d498bbe6 |

| COAD | 7870476d-f872-43c6-af9f-443be355c574 |

| COAD | 79186804-2456-4aa8-b8f4-a0fa086d6376 |

| COAD | 80933774-fa0a-43c2-bc3b-a7cdefb0163b |

| COAD | 809d0d80-536c-49ef-b8ac-d96bd79728b6 |

| COAD | 84d21e5b-67d4-41dd-b1cc-13b289678984 |

| COAD | a68feb26-054c-4e23-b792-605ee2b65e80 |

| COAD | acc62c2f-5bde-4d4e-807a-e2bf8773b49d |

| COAD | b2fb6250-c37c-4d34-b657-853b3fa2f2fd |

| COAD | b3fe0f6b-e750-4290-83db-533e93580585 |

| COAD | d134c76e-83a5-48d7-af48-5105c10a506c |

| COAD | ef5879a7-7bef-488f-b247-3f1f57b5841a |

| COAD | f4fe6fc4-f663-42df-89d1-e5991b3c32a0 |

| HNSC | 9bbf6a87-5add-462a-9720-67dbd295b8ff |

| KIRC | a6e8fee6-753f-4b33-8610-9efa61246abb |

| KIRP | 72fe472f-7c9a-4f53-aef1-31c741d23d5a |

| KIRP | 833f7265-fa2c-45d6-82d1-37751aec60f4 |

| LIHC | 36fbc8a1-0cea-4ceb-ae61-3a026b613f5e |

| LUSC | 13dd13ef-60af-4f05-be7c-514caaa4d875 |

| LUSC | 3a7f747a-53a0-46d3-b675-991bbadb013b |

| LUSC | 7257d160-9515-461f-9a9c-82eb25dd7929 |

| LUSC | 7672d5cd-582a-47ef-8697-562ae80ecb82 |

| LUSC | 81c2eb88-6377-405a-a305-a8a384b6ee1c |

| LUSC | edca18a3-37fb-4d5b-af76-690a0edb1107 |

| LUSC | f95e706b-9825-477d-95f8-5e1a98602aa2 |

| LUSC | fe5f1883-5c31-4513-b656-3bec11aeeca4 |

| OV | 35ed3cc1-a347-4f3c-98a5-767e0c0ab187 |

| READ | 4c16a42d-9023-44b0-b1e6-d7d6fa0f6b81 |

| STAD | ca57f2b6-c20c-41a3-8eda-f403dde1abf3 |

| STAD | d9de81dc-6844-433a-a5bb-7fe5d6847464 |

CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; HNSC, head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma; KIRC, kidney clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney papillary cell carcinoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma.

Chimera analysis.

SummonChimera (24) was used to search for chimeric reads between HPV18 and the human genome. Reads from a sample were aligned to HPV18 and hg19 with BLASTN. The BLASTN output files and the virus alignments were input into SummonChimera. SummonChimera was run with the default parameters. The samples used were the same as those for the single-nucleotide variant analysis.

G6PD SNP analysis.

The HeLa cell genome contains single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs1050829, which represents a change from T to a C on chromosome X at position 153,763,492 in hg19. SAMtools mpileup was used to generate the depth of reads at this position, and the frequency of SNP rs1050829 was calculated.

HPV18 strain analysis.

Variant calls for each sample were generated with the mpileup program of SAMtools (version 0.1.19; http://samtools.sourceforge.net/) for HPV18 (GenBank accession number NC_001357.1). SAMtools is a collection of utility programs to manipulate and summarize the alignments of high-throughput sequence data to a reference sequence (25). The variant calls were used to build a consensus HPV18 genome for each sample. A base position was considered mutated if the majority base at that position is not the reference base. The consensus HPV18 genomes were aligned with BLASTN (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/blast+/) to the set of 124 alphapapillomavirus 7 complete genomes (NCBI Nucleotide database query, “alphapapillomavirus 7 complete genome”) with default parameters.

RESULTS

HPV18 sequences are detected in human cancers.

While exploring TCGA databases for viral sequences (P. G. Cantalupo, J. P. Katz, and J. M. Pipas, unpublished data), we found that 164 (out of 2,766) RNA-Seq and 62 (out of 2,544) whole-exome sequencing (WXS) libraries from 15 cancers had at least one sequence read aligned to HPV18. We considered HPV18 to be present in a sequencing library if the number of virus alignments was greater than 10. Using this filter, we detected HPV18 in 10 cancers across 73 RNA-Seq and 44 WXS data sets (Tables 1 and 2). As expected, HPV18 transcription was detected in many cervical cancer (cervical squamous cell carcinoma; CESC) RNA-Seq samples (34 out of 109). A few of these had more than 100,000 alignments, and several samples had almost complete coverage of the HPV18 genome. We found RNA-Seq reads aligning to HPV18 in 39 other samples from 9 non-CESC cancers (Table 1). The maximum number of alignments to HPV18 in these samples was 1,896. We confirmed the presence of HPV18 in many of the CESC RNA-Seq samples by WXS, but we were unable to detect HPV18 by WXS for the remaining cancers.

TABLE 1.

Number of samples analyzed and number of HPV18 detectionsa

| Cancer | RS |

WXS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of samples | No. (%) with HPV18 detected | Maximum no. of alignments | No. of samples | No. (%) with HPV18 detected | Maximum no. of alignments | |

| BLCA (bladder) | 100 | 99 | ||||

| BRCA (breast) | 100 | 91 | ||||

| CESC (cervix) | 109 | 34 (31) | 142,897 | 104 | 44 (42) | 4,387,483 |

| COAD (colon) | 429 | 22 (5) | 150 | 402 | ||

| GBM (brain) | 169 | 167 | ||||

| HNSC (head and neck) | 98 | 1 (1) | 13 | 97 | ||

| KICH (kidney) | 91 | 91 | ||||

| KIRC (kidney) | 101 | 1 (1) | 1,896 | 97 | ||

| KIRP (kidney) | 101 | 2 (2) | 179 | 100 | ||

| LAML (blood) | 173 | 71 | ||||

| LGG (brain) | 100 | 94 | ||||

| LIHC (liver) | 104 | 1 (1) | 62 | 96 | ||

| LUAD (lung) | 114 | 108 | ||||

| LUSC (lung) | 99 | 8 (8) | 29 | 93 | ||

| OV (ovary) | 100 | 1 (1) | 92 | 86 | ||

| PAAD (pancreas) | 41 | 41 | ||||

| PRAD (prostate) | 100 | 93 | ||||

| READ (rectum) | 162 | 1 (1) | 92 | 159 | ||

| SKCM (skin) | 100 | 100 | ||||

| STAD (stomach) | 143 | 2 (1) | 328 | 141 | ||

| THCA (thymus) | 132 | 116 | ||||

| UCEC (uterus) | 100 | 98 | ||||

| Totals | 2,766 | 73 (3) | 142,897 | 2,544 | 44 (2) | |

RS, RNA-Seq; WXS, whole-exome sequencing; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma; KICH, kidney chromophobe carcinoma; KIRC, kidney clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney papillary cell carcinoma; LAML, acute myeloid leukemia; LGG, lower-grade glioma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma.

Alignments in non-CESC samples are similar to the integrated portion of HPV18 in HeLa cells.

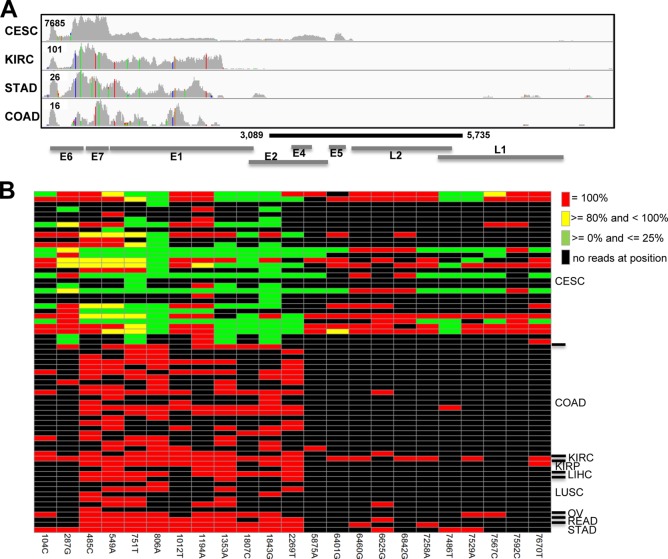

We questioned the presence of HPV18 in non-CESC samples for several reasons. First, the number of alignments to HPV18 was much lower in non-CESC samples. Second, upon closer examination, we noticed that the sequences aligning to HPV18 in non-CESC samples contained single-nucleotide variants relative to the reference genome and lacked aligned reads to the central region of the viral genome (coordinates 3089 to 5735) that encodes the E2, E4, E5, and L2 genes (Fig. 1). Both these variants (Table 3) and the deleted central region are indicative of the partial HPV18 genome that is integrated into HeLa cells (11, 13). We hypothesized that the HPV18 detected in the non-CESC samples came from HeLa nucleic acid contamination. To test this, we conducted several analyses described below.

FIG 1.

HPV18 pattern of read alignment and SNVs. (A) Whole-genome HPV18 (GenBank accession number NC_001357.1; 7,857 bp) coverage graphs showing the number of reads aligning to each base were generated for 4 samples that had the deepest coverage of HPV18 from 4 cancers. The maximum y-value is shown for each graph. The colored vertical bars in the graph represent bases that differ from the HPV18 reference sequence. The black line represents the region of the HPV18 genome that is deleted in the HeLa genome. The virus gene annotations are shown at the bottom. (B) Reads that align to HeLa SNV positions are mutated 100% of the time for all non-CESC samples. The HPV18 position and HeLa allele are shown on the x axis (columns). The rows are the 67 RNA-Seq samples in which HPV18 was detected and for which at least one HeLa SNV position was covered by at least one read. At each position, the color represents the percentage of reads that match the HeLa allele. CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; KIRC, kidney clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney papillary cell carcinoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma.

TABLE 3.

HeLa-specific HPV18 SNVs

| Gene | Position | SNV |

|---|---|---|

| E6 | 104 | T→C |

| 287 | C→G | |

| 485 | T→C | |

| 549 | C→A | |

| E7 | 751 | C→T |

| 806 | G→A | |

| E1 | 1012 | A→T |

| 1194 | C→A | |

| 1353 | T→A | |

| 1807 | T→C | |

| 1843 | T→G | |

| 2269 | C→T | |

| L1 | 5875 | C→A |

| 6401 | A→G | |

| 6460 | C→G | |

| 6625 | C→G | |

| 6842 | C→G | |

| 7258 | T→A | |

| 7486 | C→T | |

| LCRa | 7529 | C→A |

| 7567 | A→C | |

| 7592 | T→C | |

| 7670 | A→T |

LCR, long control region.

HeLa-HPV18 single-nucleotide variant analysis.

There are 23 bases that differ between the integrated region of HPV18 in the HeLa genome (GenBank accession number U89349 [13]) and the reference sequence (Table 3). Four CESC samples and two non-CESC samples (1 head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma [HNSC] and 1 lung squamous cell carcinoma [LUSC] sample) did not have any reads that overlap these variant sites; therefore, they were removed from further analysis. A heat map was generated for the remaining 67 samples (Fig. 1B), showing the percentage of reads that contain the HeLa allele at each of the 23 HeLa variant positions. In all non-CESC samples, the HeLa allele frequency was 100% at positions covered by at least one read. Additionally, the same samples did not have any reads that aligned to the deleted region of HPV18 in HeLa (Fig. 1A and data not shown). In contrast, the CESC samples displayed a range of HeLa allele frequencies of from 0% to 100% (Fig. 1B). In addition, 30 CESC samples (83%) had alignments to the deleted region (Fig. 1A and data not shown).

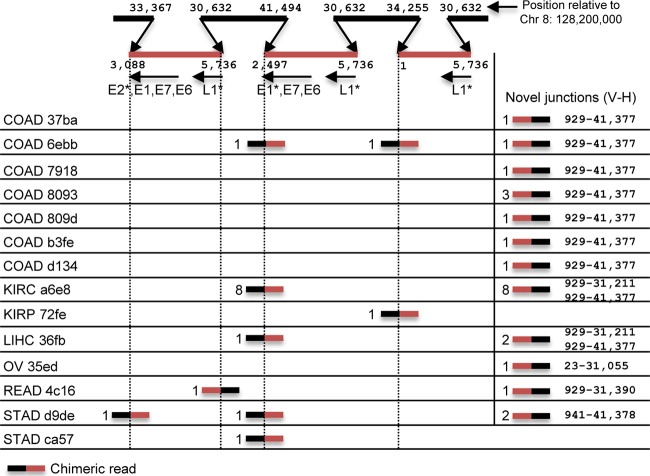

HeLa-HPV18 specific junctions were detected in non-CESC samples.

We hypothesized that if HeLa nucleic acids were present in the non-CESC samples, then a subset should include virus-human chimeric reads that match the known integration sites of HPV18 in HeLa. We searched for chimeric reads with SummonChimera (24) for all the samples in Fig. 1B. We found chimeric reads that covered a known HPV18-HeLa integration site or a novel junction in the HPV18 integration locus in many (13 out of 37) of the non-CESC samples (Fig. 2). We did not detect any chimeric reads in the region of chromosome 8 where HPV18 is integrated (128,229,000 to 128,243,000) for the 30 CESC samples. Many of the novel chimeras contain the 929 5′ splice site in E1 of HPV18 (26). Most likely, these chimeras were generated from a splicing event that fused the 929 5′ donor to a downstream acceptor site in the human genome. The precise nucleotide match of the cell-virus junction with HeLa is strong evidence that the HPV18 sequences present in these samples represents HeLa cell contamination.

FIG 2.

HeLa-HPV18 chimeric reads are found in non-CESC samples. SummonChimera was used to detect human-HPV18 chimeric reads for each sample. Chimeric reads are labeled with the number of chimeras found at that position. A simplified representation of the HPV18 integration locus (11) is shown at the top. Three HPV18 genome segments (red) are integrated in the HeLa genome (black) on chromosome 8 (Chr 8). The nucleotide numbers for human and virus at each junction are shown. HPV18 genes are listed under each integrated portion (an asterisk represents a partial gene), and the arrow indicates the direction of transcription. Novel junctions that do not correspond to the six known junctions in the integration locus are shown on the right (the genomic position for virus [V] is shown first, followed by that for human [H]).

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase SNP analysis.

The historical method to detect HeLa cell contamination was to determine the electrophoretic mobility of the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) gene. It was shown that HeLa possesses the type A+ variant of G6PD (2, 27). The genotype (SNP, rs1050829) corresponding to this phenotype changes T to a C on chromosome X at position 153,763,492 in the human genome. We calculated the frequency of SNP rs1050829 in the samples and found that for the CESC samples, only 2 (6%) had reads that contained the SNP rs1050829 (maximum frequency, 5.4%). For the non-CESC samples, 12 (35%) had reads that contained the SNP rs1050829. The maximum frequency observed was for the kidney clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) sample at 10.7%. We attempted to extend this analysis to globally analyze HeLa-specific SNPs based upon a recent report (28), but the results were inconclusive mainly due to the low coverage of the SNPs.

HPV18 strain analysis.

HPV18 is a member of the Papillomaviridae species Alphapapillomavirus 7. One possibility is that our variant and mapping results could be due to the presence of an alphapapillomavirus 7 strain closely related to HPV18. We tested this hypothesis in two ways. First, we computationally created a consensus HPV18 genome for each sample based upon the variant calls in the sample. The consensus HPV18 genomes were aligned with BLASTN to a set of 124 alphapapillomavirus 7 complete genomes. None of the genomes aligned with 100% identity, and the top hit in all the non-CESC samples is the HPV18 reference sequence (GenBank accession number NC_001357) (data not shown). Second, using BLASTN, we aligned the individual HPV18 reads in each sample to the set of 124 alphapapillomavirus 7 genomes, including an HPV18 genome that was changed at 23 base positions (Table 3) to the HeLa allele (termed HeLa-HPV18). For all the non-CESC samples save one, the genome with the most number of reads that aligned to it with 100% identity was the HeLa-HPV18 genome (data not shown). Therefore, from both these analyses, we conclude that the presence of a strain closely related to HPV18 is not present in non-CESC samples.

HeLa contamination was restricted to two sequencing centers and specific time periods.

We correlated the presence of HeLa contamination with several TCGA parameters, such as analysis date, year, sequencing machine, sequencing center, tissue source site, and sample type (tumor or normal). Contamination was limited to several dates and two sequencing centers that perform RNA-Seq for the TCGA, the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (UNC-LCCC) and the British Columbia Cancer Agency's Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre (BCCAGSC) (data not shown). All of the contamination occurred in 2011 (8% of the samples) and 2012 (0.5% of the samples). No contamination was detected in samples processed in 2010 or 2013. The contamination was limited to 18 sequencing machines (6% of the machines). There were instances where multiple samples (but not all) run at the same time on the same machine were contaminated with HeLa. Most of the contamination in the colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) samples (16 of 19) occurred on three dates in 2011—13 June, 14 June, and 30 July—on 6 different machines. HeLa contamination did not correlate with sample type, as it occurred in tumor and normal samples. Finally, there was no common tissue source site as the source for the HeLa contamination.

DISCUSSION

Is it HPV18 or HeLa?

In this report, we analyzed TCGA RNA-Seq and whole-exome sequencing (WXS) data sets to determine the presence of HPV18 in a variety of tumors. As expected, HPV18 was detected in many CESC samples. HPV18 was also detected in 9 other cancers. However, our analyses show that these alignments match the portion of the HPV18 genome that is integrated into the HeLa genome and do not represent a different strain of HPV18. In contrast to previous reports, our data suggest that HPV18 is not present in the non-CESC samples, such as the colon adenocarcinoma, rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), and normal kidney samples, as previously reported (19, 20). These findings are most likely explained by contamination with HeLa nucleic acids during sample procurement, preparation, or sequencing.

HeLa contamination was present in two TCGA sequencing centers.

The HeLa contamination was limited to the UNC-LCCC and BCCAGSC RNA sequencing centers during the years 2011 and 2012. The WXS samples that we analyzed were sequenced at the Baylor College of Medicine (BCM), Broad Institute (BI), and Washington University Genome Sequencing Center (WUGSC). Therefore, it is not surprising that we only detected HPV18 by WXS in CESC samples. A recent study reported that HPV18 was not present in whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of the same COAD and READ samples for which HPV18 was detected in the corresponding RNA-Seq analyses (20). These results make sense in light of the fact that none of the TCGA WXS and WGS samples were sequenced in the centers (UNC-LCCC and BCCAGSC) where HeLa contamination was found.

Other contamination in TCGA databases.

There are several examples of DNA contamination in TCGA. Tang et al. (19) have reported that a kidney clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) sample having alignments to hepatitis B virus came from contamination from a liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) sample. In addition, they report the contamination of plasmids containing the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in many samples. In another report, a step was added to their analysis pipeline to specifically reduce the vector contamination problem (20). During the course of our analysis, we confirmed these contaminations and identified several others. For example, we found that Dengue virus 2 (DV2) was present in two ovarian cancer (OV) tumor samples (∼250 alignments each). BLASTN searches of several of these reads matched with 100% identity to two DV2 isolates (GenBank accession numbers FJ906962.1 and FJ850121.1) (data not shown). Both accession numbers are annotated in GenBank as “Broad Institute Genome Sequencing Platform; Broad Institute Microbial Sequencing Center; Genome Resources in Dengue Consortium.” Because the Broad Institute has a Dengue virus project, we believe that these sequences are not truly present in the OV samples but rather are cross-contamination from BI sequencers. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) artifacts are not limited to TCGA. For instance, contamination of an ovarian cancer cell line with 293T cells led to the misidentification of viruses in the ovarian cancer cell line (29). Finally, as seen in our G6PD analysis, contamination of nucleic acids has the potential to introduce a population of reads containing cellular mutations which, depending upon the level of contamination and depth of sequencing, may affect variant calls.

Conclusion.

Nucleic acid contamination occurs frequently during experimentation at the bench. Most of the time this contamination is not detected, but with the advent of sensitive techniques such as PCR and deep sequencing, the contamination that was once hidden is suddenly revealed. We have shown that HeLa nucleic acid contamination (and the other contaminations described above) can lead to the misidentification of viruses. This presents a major challenge for accurately identifying viruses from NGS data, whether the samples are cancer tissues or normal tissues used for microbiome studies. We now add HeLa cell contamination to the growing list of artifacts that should be accounted for when analyzing human sequencing data for the presence of viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant CA170248 to J.M.P.

We gratefully thank the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Simulation and Modeling (http://www.sam.pitt.edu/) for use of their state-of-the-art high-performance computing (HPC) cluster and for technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gey GO, Coffman WD, Kubicek MT. 1952. Tissue culture studies of the proliferative capacity of cervical carcinoma and normal epithelium. Cancer Res 12:264–265. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gartler SM. 1968. Apparent Hela cell contamination of human heteroploid cell lines. Nature 217:750–751. doi: 10.1038/217750a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson-Rees WA, Daniels DW, Flandermeyer RR. 1981. Cross-contamination of cells in culture. Science 212:446–452. doi: 10.1126/science.6451928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucey BP, Nelson-Rees WA, Hutchins GM. 2009. Henrietta Lacks, HeLa cells, and cell culture contamination. Arch Pathol Lab Med 133:1463–1467. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.9.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nardone RM. 2007. Eradication of cross-contaminated cell lines: a call for action. Cell Biol Toxicol 23:367–372. doi: 10.1007/s10565-007-9019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masters JR. 2002. HeLa cells 50 years on: the good, the bad and the ugly. Nat Rev Cancer 2:315–319. doi: 10.1038/nrc775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jäger W, Horiguchi Y, Shah J, Hayashi T, Awrey S, Gust KM, Hadaschik BA, Matsui Y, Anderson S, Bell RH, Ettinger S, So AI, Gleave ME, Lee IL, Dinney CP, Tachibana M, McConkey DJ, Black PC. 2013. Hiding in plain view: genetic profiling reveals decades old cross contamination of bladder cancer cell line KU7 with HeLa. J Urol 190:1404–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacLeod RA, Dirks WG, Matsuo Y, Kaufmann M, Milch H, Drexler HG. 1999. Widespread intraspecies cross-contamination of human tumor cell lines arising at source. Int J Cancer 83:555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee R. 2007. Cell biology. Cases of mistaken identity. Science 315:928–931. doi: 10.1126/science.315.5814.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz E, Freese UK, Gissmann L, Mayer W, Roggenbuck B, Stremlau A, zur Hausen H. 1985. Structure and transcription of human papillomavirus sequences in cervical carcinoma cells. Nature 314:111–114. doi: 10.1038/314111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adey A, Burton JN, Kitzman JO, Hiatt JB, Lewis AP, Martin BK, Qiu R, Lee C, Shendure J. 2013. The haplotype-resolved genome and epigenome of the aneuploid HeLa cancer cell line. Nature 500:207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thierry F. 2009. Transcriptional regulation of the papillomavirus oncogenes by cellular and viral transcription factors in cervical carcinoma. Virology 384:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meissner JD. 1999. Nucleotide sequences and further characterization of human papillomavirus DNA present in the CaSki, SiHa and HeLa cervical carcinoma cell lines. J Gen Virol 80:1725–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crow JM. 2012. HPV: the global burden. Nature 488:S2–S3. doi: 10.1038/488S2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson C, Schwartz S. 2013. Regulation of human papillomavirus gene expression by splicing and polyadenylation. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:239–251. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng JY, Sheu LF, Meng CL, Lee WH, Lin JC. 1995. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in colorectal carcinomas by polymerase chain reaction. Gut 37:87–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gornick MC, Castellsague X, Sanchez G, Giordano TJ, Vinco M, Greenson JK, Capella G, Raskin L, Rennert G, Gruber SB, Moreno V. 2010. Human papillomavirus is not associated with colorectal cancer in a large international study. Cancer Causes Control 21:737–743. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9502-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salepci T, Yazici H, Dane F, Topuz E, Dalay N, Onat H, Aykan F, Seker M, Aydiner A. 2009. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA by polymerase chain reaction and southern blot hybridization in colorectal cancer patients. J BUON 14:495–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang KW, Alaei-Mahabadi B, Samuelsson T, Lindh M, Larsson E. 2013. The landscape of viral expression and host gene fusion and adaptation in human cancer. Nat Commun 4:2513. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salyakina D, Tsinoremas NF. 2013. Viral expression associated with gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas in TCGA high-throughput sequencing data. Hum Genomics 7:23. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmieder R, Edwards R. 2011. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 27:863–864. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. 2013. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform 14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz JP, Pipas JM. 2014. SummonChimera infers integrated viral genomes with nucleotide precision from NGS data. BMC Bioinform 15:348. doi: 10.1186/s12859-014-0348-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Meyers C, Wang HK, Chow LT, Zheng ZM. 2011. Construction of a full transcription map of human papillomavirus type 18 during productive viral infection. J Virol 85:8080–8092. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00670-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida A, Watanabe S, Gartler SM. 1971. Identification of HeLa cell glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochem Genet 5:533–539. doi: 10.1007/BF00485671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landry JJ, Pyl PT, Rausch T, Zichner T, Tekkedil MM, Stutz AM, Jauch A, Aiyar RS, Pau G, Delhomme N, Gagneur J, Korbel JO, Huber W, Steinmetz LM. 2013. The genomic and transcriptomic landscape of a HeLa cell line. G3 (Bethesda) 3:1213–1224. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.005777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borozan I, Wilson S, Blanchette P, Laflamme P, Watt SN, Krzyzanowski PM, Sircoulomb F, Rottapel R, Branton PE, Ferretti V. 2012. CaPSID: a bioinformatics platform for computational pathogen sequence identification in human genomes and transcriptomes. BMC Bioinform 13:206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]