ABSTRACT

The NS2A protein of dengue virus (DENV) has eight predicted transmembrane segments (pTMSs; pTMS1 to pTMS8). NS2A has been shown to participate in RNA replication, virion assembly, and the host antiviral response. However, the role of the amino acid residues within the pTMS regions of NS2A during the virus life cycle is poorly understood. In the study described here, we explored the function of DENV NS2A by introducing a series of double or triple alanine substitutions into the C-terminal half (pTMS4 to pTMS8) of NS2A in the context of a DENV infectious clone or subgenomic replicon. Fourteen (8 within pTMS8) of 35 NS2A mutants displayed a lethal phenotype due to impairment of RNA replication by a replicon assay. Three NS2A mutants with mutations within pTMS7, the CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants, displayed similar phenotypes, low virus yields (>100-fold reduction), wild-type-like replicon activity, and low infectious virus-like particle yields by transient trans-packaging experiments, suggesting a defect in virus assembly and secretion. The sequencing of revertant viruses derived from CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutant viruses revealed a consensus reversion mutation, leucine (L) to phenylalanine (F), at codon 181 within pTMS7. The introduction of an L181F mutation into a full-length NS2A mutant, i.e., the CM20, CM25, and CM27 constructs, completely restored wild-type infectivity. Notably, L181F also substantially rescued the other severely RNA replication-defective mutants with mutations within pTMS4, pTMS6, and pTMS8, i.e., the CM2, CM3, CM13, CM31, and CM32 mutants. In conclusion, the results revealed the essential roles of pTMS4 to pTMS8 of NS2A in RNA replication and/or virus assembly and secretion. The intramolecular interaction between pTMS7 and pTMS4, pTMS6, or pTMS8 of the NS2A protein was also implicated.

IMPORTANCE The reported characterization of the C-terminal half of dengue virus NS2A is the first comprehensive mutagenesis study to investigate the function of flavivirus NS2A involved in the steps of the virus life cycle. In particular, detailed mapping of the amino acid residues within the predicted transmembrane segments (pTMSs) of NS2A involved in RNA replication and/or virus assembly and secretion was performed. A revertant genetics study also revealed that L181F within pTMS7 is a consensus reversion mutation that rescues both RNA replication-defective and virus assembly- and secretion-defective mutants with mutations within the other three pTMSs of NS2A. Collectively, these findings elucidate the role played by NS2A during the virus life cycle, possibly through the intricate intramolecular interaction between pTMS7 and other pTMSs within the NS2A protein.

INTRODUCTION

Most flaviviruses are transmitted by mosquito or tick vectors and cause serious human and animal diseases (1, 2). Certain members of the genus Flavivirus are reemerging global health threats, especially in urban areas of developing countries (3). Flaviviruses include dengue virus (DENV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), West Nile virus (WNV), yellow fever virus (YFV), and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV). There are four different serotypes of dengue virus, DENV serotype 1 (DENV1) to DENV4. DENV has been circulating in over 100 countries, and an estimated 2.5 billion people live in areas in which dengue is epidemic (4–6). DENV infection often leads to dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome (7–9).

Flaviviruses are enveloped RNA viruses containing a positive-sense, single-stranded genomic RNA of 10.5 to 11 kb in length. The genomic RNA consists of a 5′ untranslated region (UTR) (10), a single open reading frame, and a 3′ UTR. After infection of the host cells, the genomic RNA is translated into a large polyprotein that is then cleaved into three structural proteins (C, prM, and E) and seven nonstructural (NS) proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) by cellular and viral proteases to initiate viral replication (11–13). The structural proteins are components of the virion, while the nonstructural proteins are mainly involved in viral RNA replication (14) and the host immune response (15).

Among these flavivirus NS proteins, NS2A is a small (molecular mass, 22 kDa), hydrophobic transmembrane protein (16, 17) that plays a critical role in the virus life cycle (14, 18, 19). The N and C termini of NS2A are processed by a membrane-bound host protease and NS2B/NS3 viral protease, respectively (12, 20). Kunjin virus (KUNV) NS2A can interact with the 3′ UTR of viral RNA and other components of the replication complex, implying the involvement of NS2A in viral RNA replication (14). In addition to its role as a component of the replication complex, several studies have shown that flavivirus NS2A also participates in the assembly and secretion of the virion (17–19, 21, 22). For example, the mutation of lysine 198 to serine (K198S) in YFV NS2A had no effect on viral RNA synthesis but blocked the production of infectious virus (18). Reversion mutations in the YFV NS3 helicase domain could restore infectious virus production of virus mutants harboring the K198S mutation, implying a protein-protein interaction between the YFV NS2A and NS3 proteins. Similarly, a single amino acid substitution at position 59 (from isoleucine to asparagine [I59N]) in KUNV NS2A reduced the production of virus-like particles (VLPs) but did not affect genomic replication (19, 22). A second-site reversion mutation at position 149 (from threonine to proline [T149P]) in KUNV NS2A could rescue the defect in virus assembly and secretion and virus production of virus mutants bearing the NS2A-I59N mutation, suggesting a potential interaction between codons 59 and 149. Several lines of evidence have shown that flavivirus NS2A is also involved in the interferon response (15, 23–26) and virus-induced cytopathic effects (CPEs) (27, 28). Recently, the topological study of DENV NS2A suggested that NS2A has eight predicted transmembrane segments (pTMSs; pTMS1 to pTMS8) and five integral transmembrane segments (pTMS3, pTMS4, pTMS6 to pTMS8) that span the lipid bilayer of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. A mutagenesis study within the first integral transmembrane segment (amino acids 69 to 93 within pTMS3) revealed that the R84A mutation did not affect viral RNA synthesis but blocked the intracellular formation of infectious virions (17). The other mutagenesis study revealed that several NS2A mutations, G11A, E20A, E100A, Q187A, and K188A, impaired virion assembly without specifically affecting viral RNA synthesis (21). Despite the many studies on the NS2A protein discussed above, the detailed map of the amino acids of the flavivirus NS2A protein essential for the stages of the virus life cycle remains largely uncertain. The role of the transmembrane segments within NS2A involved in the virus life cycle is also unclear.

Here, we sought to dissect the functions of DENV2 NS2A and identify the amino acid residues within the C-terminal half of NS2A (pTMS4 to pTMS8) that are essential for the virus life cycle through alanine scanning mutagenesis. Functional analyses of NS2A mutants bearing alanine substitution mutations revealed three major phenotypes. Approximately 43% of NS2A mutants displayed a spreading ability, virus production, and plaque size similar to those of the wild-type (WT) virus. Forty percent of NS2A mutants displayed lethal phenotypes. Some of the remaining NS2A mutants mainly exhibited an assembly- and secretion-defective phenotype: a lower virus titer, inefficient virus assembly and secretion, and no apparent defect in viral RNA replication. A consensus reversion mutation at position 181 within pTMS7 of the NS2A protein (from leucine to phenylalanine [L181F]) was identified and shown to greatly restore the infectivity of several NS2A mutants defective in either RNA replication or virus assembly and secretion. These results provide comprehensive knowledge regarding the functions of DENV NS2A, and the specific amino acids and transmembrane segments responsible for NS2A functions were also identified. The positions and properties of the rescuing mutations revealed unexpected relationships between different pTMSs of NS2A, and this information provides important clues as to how the intramolecular interactions between pTMSs of NS2A regulate virus replication and virus assembly and secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), alpha-modified minimal essential medium (alpha-MEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and RPMI 1640 were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma (Poole, United Kingdom).

Cell lines.

HEK-293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Baby hamster kidney (BHK21) clone 15 cells were kindly provided by R. Beatty (Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA) and cultured in alpha-MEM supplemented with 5% FBS at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. BHK21 clone 13 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Escherichia coli, yeast methods, and strains.

Frozen, competent E. coli strain C41, a derivative of BL21(DE3) (29), was purchased from OverExpress Inc. C41 was cultured in 2YT medium (16 g of Bacto tryptone, 10 g of yeast extract, and 5 g of NaCl in 1 liter of distilled water [pH 7.2]) or agar plates. Standard yeast medium and methods were used (30). Saccharomyces cerevisiae YPH857 was purchased from ATCC. The genotype of YPH857 is MATα ade2-101 lys2-801 ura3-52 trp1-Δ63 HIS5 CAN1 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 cyh2. Competent yeast cells were prepared using the lithium acetate procedure (30).

Plaque-forming assay.

The plaque-forming assay was used to determine the viral titer. BHK21 clone 15 cells were seeded in 12-well plates (4 × 104 cells per well) containing 1 ml of medium and incubated overnight. Then, 0.1 ml of serially diluted virus solution was added to ∼70 to 80% confluent BHK21 cells. After a 6-h adsorption period, the virus solutions were replaced with DMEM containing 0.75% methylcellulose (catalog number M-0512; Sigma) and 2% FBS. On day 6 after DENV infection, the methylcellulose solution was removed from the wells and the cells were fixed and stained with naphthol blue-black solution (0.1% naphthol blue-black, 1.36% sodium acetate, 6% glacial acetic acid) (31). The numbers of PFU per milliliter of DENV were then determined.

Plasmid construction.

All primers used for plasmid construction are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. To generate NS2A mutant viruses containing an alanine substitution mutation, a DNA-launched infectious clone of DENV2 strain 16681, pTight-DENV2, was employed for the construction of an NS2A mutant plasmid (32). The plasmid pTight-DENV2 contains a minimal cytomegalovirus (CMVmin) promoter derived from the pTRE-Tight vector (BD Bioscience), a full-length DENV2 genome (strain 16681), a hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme sequence, and the simian virus 40 (SV40) poly(A) signal. To facilitate the mutagenesis of the NS2A region, a unique XbaI restriction site was introduced into the NS1 gene. To generate alanine substitution mutations within the NS2A gene in the context of pTight-DENV2, the cDNA fragments from nucleotide positions 3044 to 4423 were amplified by site-directed mutagenesis using the corresponding primer (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Amplified cDNA fragments were then cotransformed with pTight-DENV2, which was linearized with XbaI and EcoRV, into yeast strain YPH857 to generate NS2A mutant plasmids. Recombinant DNA techniques were used according to standard procedures (33–35), and the sequences of all NS2A mutant plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

To analyze the effects of NS2A mutations on RNA replication, a DNA-launched replicon, pCMV-DV2Rep, was derived from pTight-DENV2 and generated by the replacement of the region coding for the structural proteins core, prM, and E in pTight-16681 with humanized Renilla luciferase (hRluc), the foot-and-mouth disease virus NS2A (FMDV2A) cleavage site, a neomycin resistance gene (Neo), an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES), and the C-terminal 24 amino acids of E (E24) (36). To generate alanine substitution mutations within the NS2A gene in the context of pCMV-DV2Rep, the cDNA fragments from nucleotide positions 3044 to 4423 were amplified by site-directed mutagenesis using the corresponding primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and cotransformed with XbaI- and EcoRV-linearized pCMV-DV2Rep into yeast strain YPH857. All mutations in the resulting plasmids were confirmed by sequence analysis.

To generate replicon-packaging plasmids, the DENV2 CprME gene fragment from nucleotide positions 97 to 2421 was amplified by site-directed mutagenesis using the primer pair XmaI/kozak/Core/F and Env/stop/XmaI/R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Amplified cDNA fragments were then cotransformed with the XmaI-linearized pSCA, a modified Semliki forest virus (SFV) expression vector (37), into yeast strain YPH857, resulting in the pSCA-DENV2-CprME plasmid.

DNA transfection.

HEK-293 cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates containing 1 ml of medium and cultured overnight. Approximately 0.25 μg of pTight-DENV2 or NS2A mutant plasmid and 0.25 μg of pTET-OFF (BD Bioscience) were mixed with 1 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in 100 μl of Opti-MEM medium. The mixture was then added to HEK-293 cells in 12-well plates and incubated at 37°C. The phenotypes of the transfected cells and viruses derived from the transfected cells were determined at 5 or 7 days posttransfection.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) to detect viral antigens.

Transfected HEK-293 cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature, permeabilized with methanol for 15 min at 4°C, and blocked with 2% horse serum in PBS. The cells were stained with 0.5 μg/ml anti-DENV prM protein antibody (mouse monoclonal antibody HB-114; ATCC) (38). Following several washes with PBS, the cells were incubated with an Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG antibody (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). After washing, images were acquired using a Leica DMIRB microscope equipped with CoolSNAP cooled charge-coupled-device cameras and Empix Northern Eclipse image software.

Transient replicon activity assay of the DNA-launched DENV replicon.

The transient replicon activity assay was performed to monitor the replication efficiency of DENV2 replicons as previously reported (36). BHK21 clone 13 cells were plated in 24-well plates (1 × 104 cells per well) and cotransfected with 0.1 μg pCMV-DV2Rep or NS2A mutant plasmid and 0.1 μg pTET-OFF using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. At 24 h posttransfection, doxycycline was added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml to turn off the DENV gene expression driven by the CMVmin promoter. To perform the luciferase assays, at 24 h and 72 h posttransfection, the medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS, lysed by adding 100 μl of lysis buffer (Renilla luciferase assay system; Promega), and assayed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Renilla luciferase assay system; Promega). The luciferase activity was measured using a GloMAX 20/20 luminometer (Promega), and replication efficiency was calculated by determination of the ratio of luciferase activity obtained at 72 h to the value obtained at 24 h posttransfection and compared with that of the WT replicon.

Western blot analysis.

Protein lysates of transfected cells were washed with PBS and then lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.2% SDS) containing protease inhibitors (Roche). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and then transferred to a 0.2-μm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare). The membrane was blocked with nonfat dry milk (5%, wt/vol) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with blocking buffer containing mouse anti-DENV core antibody (1:4,000 dilution; 6F3.1), mouse anti-DENV envelope (1:5,000 dilution; 4G2), mouse anti-DENV NS3 (1:3,000 dilution; catalog number YH0034; Yao-Hong Biotechnology Inc.), or rabbit anti-GAPDH (anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; 1:3,000 dilution; catalog number GTX100118; GeneTex Inc.) overnight at 4°C. After washes in TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG polyclonal antibodies (GeneTex, Inc.). Following several washes in TBST, the enzyme reaction was developed using a chemiluminescent HRP substrate (catalog number WBKLS0500; Immobilon Western; Millipore Corporation), and the film was exposed.

Packaging of VLPs.

DENV VLPs were generated by the trans supply of viral structural proteins to luciferase-expressing replicons. BHK21 clone 13 cells were plated in 12-well plates (1 × 104 cells per well) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. One microgram of pSCA-DENV2-CprME was then transfected into one well with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The pSCA-DENV2-CprME plasmid was used to express the structural proteins (C, prM, E) of DENV2. At 24 h posttransfection, the transfected cells were subjected to a second round of transfection with 1 μg of pCMV-DV2Rep or NS2A mutant plasmid and 0.4 μg of pTET-OFF. Twenty-four hours later, the culture medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium. The culture supernatants from the transfected cells were collected 48 h after the second transfection and used to infect naive HEK-293 cells. To perform the luciferase assays, at 72 h postinfection, the infected cells were washed with PBS, lysed by adding lysis buffer, and then assayed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Renilla luciferase assay system; Promega). Luciferase activities were measured using a GloMAX 20/20 luminometer (Promega).

ELISA.

An antigen-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to detect and quantify the level of secretion of virus particles harvested from HEK-293 cells transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids (39). Briefly, flat-bottom 96-well MaxiSorp Nunc-Immuno plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with 50 μl of rabbit anti-DENV2 VLP serum at 1:500 in carbonate buffer (0.015 M Na2CO3, 0.035 M NaHCO3, pH 9.6) and incubated overnight at 4°C, and the wells were blocked with 200 μl of 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. Harvested culture medium and normal HEK-293 cell culture fluid were titrated 2-fold in PBS, 50 μl was added to wells in duplicate, and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and washed 5 times with 200 μl of PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (0.1% PBST). Captured antigens were detected by adding 50 μl of anti-DENV2 mouse hyperimmune ascitic fluid (MHAF) at 1:2,000 in blocking buffer, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and washed 5 times. Fifty microliters of HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at 1:6,000 in blocking buffer was added to the wells, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C to detect MHIAF. Subsequently, the plates were washed 10 times. Bound conjugate was detected with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Enhanced K-Blue TMB; Neogen Corp., Lexington, KY), the plates were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, and the reaction was stopped with 2 N H2SO4. The A450s of the reactions were measured using a Tecan Sunrise microplate reader (Tecan, Grödig, Austria). Endpoint antigen secretion titers from three independent experiments were determined from twice the average optical density (OD) of the negative-control antigen by using a sigmoidal dose-response equation in GraphPad Prism (version 6.0) software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Alanine scanning mutagenesis in the C-terminal half of the DENV2 NS2A protein.

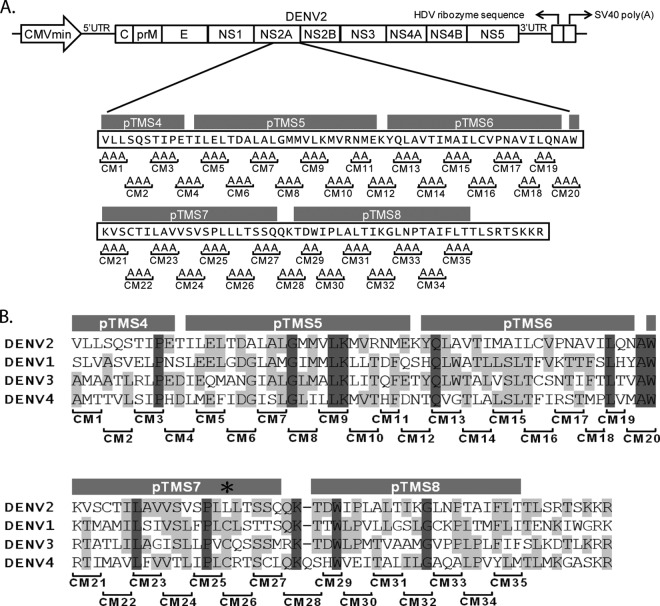

To identify which amino acid residues are required for NS2A functions, alanine substitution mutations in the C-terminal half (amino acids 109 to 218) of NS2A were introduced into pTight-DENV2, a DNA-launched infectious clone bearing the full-length genome of the DENV2 16681 strain (32). The pTight-DENV2 plasmid contains a minimal cytomegalovirus (CMVmin) promoter regulated by the upstream tetracycline response elements, a full-length DENV2 genome, an HDV ribozyme sequence, and the SV40 poly(A) signal. Transcriptional expression of the infectious full-length DENV2 RNA genome from the plasmid is under the control of a CMVmin promoter, and the 3′ terminus of the transcript is processed by the HDV ribozyme sequence (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, the amino acid sequences of the C-terminal halves of the NS2A proteins from various serotypes of DENV were aligned, and conserved amino acid residues are highlighted. Mutants with these alanine substitution mutations were designated CM1 through CM35 (Fig. 1A), and CM1 to CM4, CM5 to CM11, CM12 to CM19, CM20 to CM27, and CM28 to CM35 were located in pTMS4, pTMS5, pTMS6, pTMS7, and pTMS8, respectively. All mutant viruses were harvested by transfecting the mutant plasmids into cells and characterized using a panel of functional analyses.

FIG 1.

Schematic diagram of alanine substitution mutations within the C-terminal half of NS2A of a DNA-launched DENV2 infectious clone. Production of the full-length DENV2 (strain 16681) RNA genome is regulated by the minimal cytomegalovirus CMVmin promoter, and the 3′ terminus of the transcript is processed by HDV ribozyme sequences. A series of double or triple alanine substitution mutations was introduced from amino acids 109 to 209 of NS2A and named CM1 through CM35. pTMSs pTMS4 to pTMS8 were proposed by Shi and colleagues (17). (B) Sequence alignment of the C-terminal half (amino acids 109 to 218) of the NS2A protein among four dengue virus serotypes. The sequence of the C-terminal half of the DENV2 (strain 16681) NS2A protein is aligned with the sequences for DENV1 (strain Hawaii), DENV3 (strain H87), and DENV4 (strain H241). Identical residues are indicated by dark gray shading, while conserved residues are indicated by light gray shading. Amino acid residue 181 is indicated by an asterisk. The locations of the alanine substitution mutations are shown below the alignment.

Characterization and phenotypes of NS2A mutant viruses.

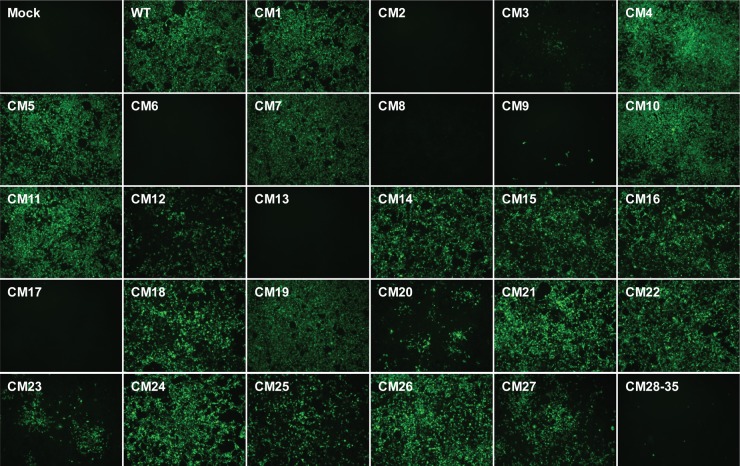

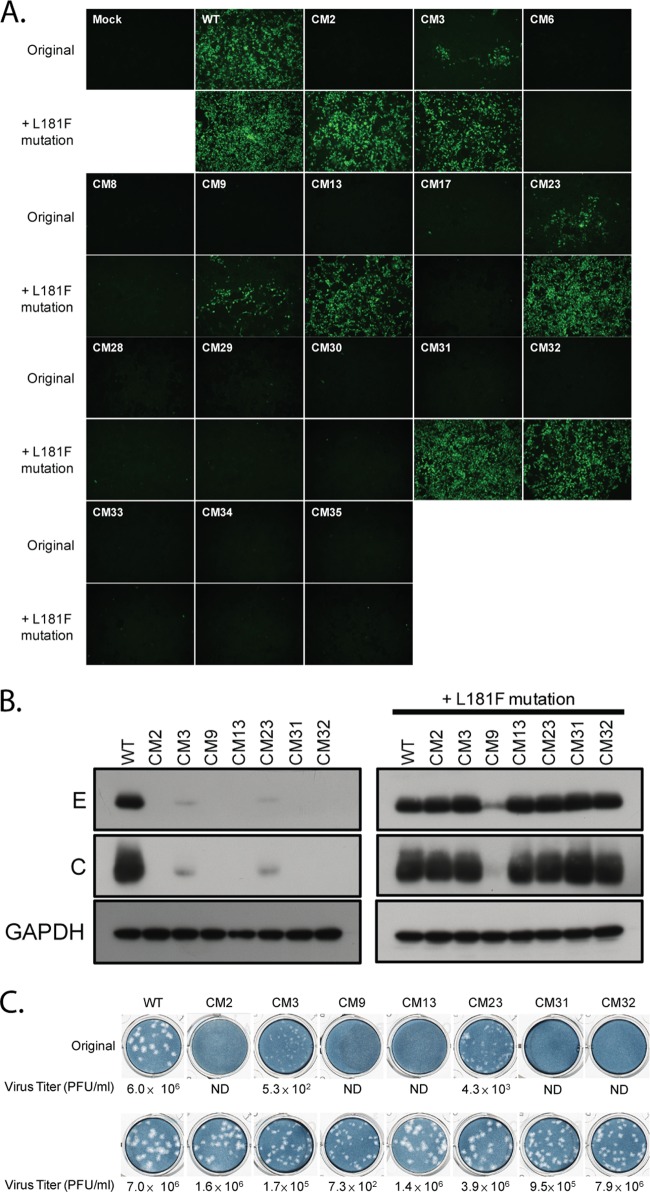

To determine the effects of the alanine substitution mutations within the C-terminal half of DENV2 NS2A on DENV2 infectivity, WT or NS2A mutant plasmids were cotransfected with the pTET-OFF plasmid into HEK-293 cells. Plasmid pTET-OFF expresses a tetracycline-responsive transcriptional activator that turns on the CMVmin promoter and drives the expression of the DENV2 transcripts. At 7 days posttransfection, the transfected cells were examined by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for DENV2 prM protein. As shown in Fig. 2, these NS2A mutants could be classified into three phenotype groups on the basis of the results of IFA. The first group contained the CM1, CM4, CM5, CM7, CM10, CM11, CM14, CM15, CM16, CM18, CM19, CM21, CM22, CM24, and CM26 mutants, which had virus spreading activity similar to that of the WT. The second group contained the CM2, CM6, CM8, CM9, CM13, CM17, CM28, CM29, CM30, CM31, CM32, CM33, CM34, and CM35 mutants, which displayed a lethal phenotype, indicating that the substituted amino acids in these NS2A mutants were indispensable for virus infectivity. Notably, all the mutants with substitutions residing in pTMS8 (CM28 to CM35) displayed lethal phenotypes, suggesting that pTMS8 is required for virus infectivity. The third group included the CM3, CM12, CM20, CM23, CM25, and CM27 mutants, which showed mild to moderate defects in virus spreading capability.

FIG 2.

Effects of NS2A mutations on DENV2 infectivity. HEK-293 cells were transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids. At 7 days posttransfection, the transfected cells were fixed and analyzed for the presence of the DENV2 prM protein by IFA. Magnifications, ×100.

To further quantitatively evaluate the difference in virus spreading activity between the WT and NS2A mutant viruses, the virus titer and plaque size of viruses prepared from HEK-293 cells transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids were determined by the plaque formation assay. We first monitored the growth kinetics of WT viruses derived from cells transfected with WT DENV infectious cDNA clone pTight-DENV2. Maximum virus titers were reached at 5 days posttransfection. The virus titers reached a plateau after 5 days posttransfection (data not shown). Therefore, we quantitatively measured the titers of either WT or NS2A mutant viruses derived from cells at either 5 or 7 days posttransfection (Table 1). Consistent with the IFA results, the virus titer and plaque sizes of the NS2A mutants without prominent defects were similar to those of the WT virus or the mutant viruses were slightly defective. These mutants included CM1, CM4, CM5, CM7, CM10, CM11, CM14, CM15, CM16, CM18, CM19, CM21, CM22, CM24, and CM26. The virus titers for the CM2, CM6, CM8, CM9, CM13, CM17, CM28, CM29, CM30, CM31, CM32, CM33, CM34, and CM35 mutants, which had a lethal phenotype, were nondetectable, suggesting that the amino acid residues changed in these NS2A mutants were necessary for infectious virus production. The virus titers for NS2A mutants CM3, CM12, CM20, CM23, CM25, and CM27 were 100- to 100,000-fold lower than those for the WT virus at either 5 or 7 days posttransfection. These NS2A mutants also had smaller plaque sizes. These data indicate that the CM3, CM12, CM20, CM23, CM25, and CM27 mutants had a mild to moderate defect in infectious virus production. NS2A mutant viruses, e.g., CM3, CM12, CM20, CM23, CM25, and CM27, harvested from the transfected cells at 7 days posttransfection were also sequenced, and all the original mutations were found in the sequences of the recovered virus genomes. This ruled out the possibility of quick reversions for those NS2A mutants.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypes of NS2A mutant viruses

| Virus | pTMS | Immunofluorescence distributiona | Virus titer (PFU/ml)b |

Plaque diam (mm)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 dpt | 7 dpt | ||||

| Wild type | ++++ | 2.6 × 106 | 3.2 × 106 | 1.48 ± 0.05 | |

| CM1 | 4 | ++++ | 8.2 × 106 | 1.6 × 106 | 1.44 ± 0.03 |

| CM2 | 4 | − | <10 | <10 | ND |

| CM3 | 4 | + | 4.3 × 10 | 9.7 × 102 | 0.45 ± 0.06 |

| CM4 | 4 | ++++ | 5.8 × 105 | 7.0 × 105 | 1.41 ± 0.03 |

| CM5 | 5 | ++++ | 6.9 × 106 | 1.4 × 106 | 1.45 ± 0.04 |

| CM6 | 5 | − | <10 | <10 | ND |

| CM7 | 5 | ++++ | 2.1 × 105 | 4.3 × 105 | 1.34 ± 0.03 |

| CM8 | 5 | − | <10 | <10 | ND |

| CM9 | 5 | − | <10 | <10 | ND |

| CM10 | 5 | +++ | 3.6 × 105 | 1.8 × 106 | 1.44 ± 0.04 |

| CM11 | 5 | ++++ | 3.0 × 105 | 3.0 × 106 | 1.45 ± 0.02 |

| CM12 | 6 | ++ | 1.8 × 102 | 1.2 × 103 | 0.48 ± 0.09 |

| CM13 | 6 | − | <10 | <10 | ND |

| CM14 | 6 | +++ | 1.1 × 105 | 3.1 × 105 | 1.41 ± 0.04 |

| CM15 | 6 | +++ | 2.3 × 105 | 4.7 × 105 | 1.39 ± 0.03 |

| CM16 | 6 | +++ | 1.2 × 105 | 2.1 × 105 | 1.37 ± 0.04 |

| CM17 | 6 | − | <10 | <10 | ND |

| CM18 | 6 | +++ | 1.1 × 105 | 4.7 × 105 | 1.39 ± 0.04 |

| CM19 | 6 | ++++ | 2.6 × 106 | 2.2 × 106 | 1.45 ± 0.04 |

| CM20 | 7 | ++ | 2.3 × 103 | 1.2 × 104 | 0.52 ± 0.04 |

| CM21 | 7 | ++++ | 2.8 × 105 | 2.6 × 106 | 1.43 ± 0.03 |

| CM22 | 7 | ++++ | 1.5 × 106 | 8.3 × 105 | 1.34 ± 0.05 |

| CM23 | 7 | ++ | 2.6 × 103 | 6.7 × 104 | 0.73 ± 0.05 |

| CM24 | 7 | ++++ | 4.6 × 106 | 4.9 × 106 | 1.45 ± 0.04 |

| CM25 | 7 | +++ | 8.2 × 102 | 1.1 × 103 | 0.73 ± 0.05 |

| CM26 | 7 | ++++ | 3.3 × 105 | 5.0 × 105 | 1.34 ± 0.04 |

| CM27 | 7 | +++ | 1.8 × 103 | 8.0 × 104 | 0.80 ± 0.06 |

| CM28 to CM35 | 8 | − | <10 | <10 | ND |

Detection of the viral prM protein by IFA in transfected HEK-293 cells at 7 days posttransfection. The percentages of positively stained cells were scored as 0 (−), 1 to 25% (+), 26 to 50% (++), 51 to 75% (+++), or 76 to 100% (++++) fluorescent anti-prM antibody-positive cells.

The virus titer was determined by plaque-forming assay on BHK21 cells at 5 or 7 days posttransfection (dpt). The plaque-forming assay was performed in triplicate, and the mean values are shown. The limit of detection of the plaque-forming assay was 10 PFU/ml.

The plaque size was measured with a micrometer, and the data are averages for 10 independent plaques. ND, not detectable.

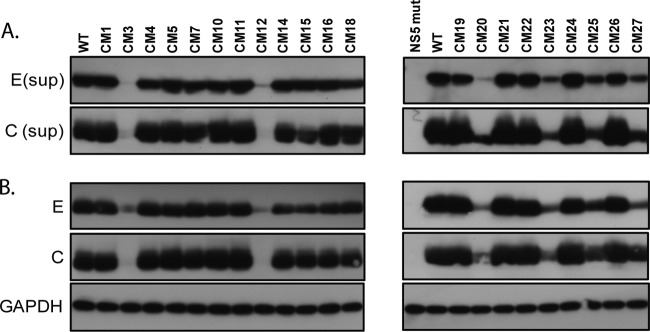

To compare the release and expression of viral structural proteins in HEK-293 cells transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids, the culture supernatants and cell lysates prepared from transfected cells were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-DENV envelope (4G2) and anti-DENV core (6F3.1) monoclonal antibodies at 7 days posttransfection. The virus mutants displaying undetectable levels in plaque-forming assays and IFAs were excluded from the Western blot analysis. The results of the Western blot analysis are presented in Fig. 3A and B. The release and expression of the DENV E and C proteins in the WT and certain NS2A mutants (CM1, CM4, CM5, CM7, CM10, CM11, CM14, CM15, CM16, CM18, CM19, CM21, CM22, CM24, and CM26) were comparable. In contrast, the release of viral proteins from HEK-293 cells transfected with the CM3, CM12, CM20, and CM23 mutants was greatly reduced, and the release from HEK-293 cells transfected with the CM25 and CM27 mutants was reduced. We also observed that the intracellular levels of the C and E proteins in CM3, CM12, CM20, CM23, CM25, and CM27 mutant-transfected cells (Fig. 3B) were reduced compared to those in the WT.

FIG 3.

Release and expression of viral structural proteins from cells transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids. HEK-293 cells were transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids. At 7 days posttransfection, the supernatants (sup) (A) and cell lysates (B) prepared from the transfected cells were analyzed by Western blot analysis using anti-DENV envelope (E; 4G2) and anti-DENV core (C; 6F3.1) antibodies. The loading control of the cell lysates was determined by use of the anti-GAPDH antibody.

Forty-three percent of NS2A mutants with mutations within the C-terminal half of NS2A displayed no apparent defect in viral RNA replication.

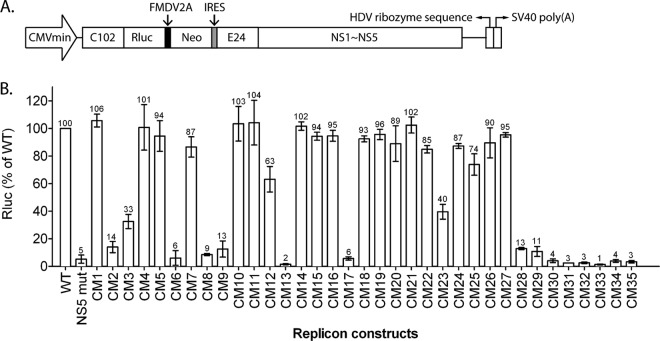

To determine whether the decrease in the infectivity of various NS2A mutants results from the defect in viral RNA replication, alanine substitution mutations were introduced into a DNA-launched DENV2 replicon plasmid, pCMV-DV2Rep (Fig. 4A) (36). The transcription of the replicon RNA was driven by the CMVmin promoter, and the integrity of the 3′ end was preserved by using an inverted HDV ribozyme sequence. NS2A mutant replicon plasmids were cotransfected with pTET-OFF into BHK21 cells. After 24 h, the transfected cells were treated with doxycycline to terminate the pTight promoter activity and turn off the transcription of the DENV replicon. The luciferase activities of the transfected cells were measured at 24 h and 72 h posttransfection. The replication efficiency was calculated by determination of the ratio of luciferase activity obtained at 72 h to the value obtained at 24 h posttransfection and compared with the activity of the WT replicon (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the results of IFA and plaque-forming analysis, replicons bearing the CM1, CM4, CM5, CM7, CM10, CM11, CM14, CM15, CM16, CM18, CM19, CM21, CM22, CM24, and CM26 mutants exhibited a replication capacity similar to that of the WT, indicating that the mutations in these mutants did not interfere greatly with DENV RNA replication. Replicons bearing the CM2, CM6, CM8, CM9, CM13, CM17, and CM28 to CM35 mutants displayed lethal phenotypes close to the phenotype of the negative control (an NS5 mutant [NS5 mut]), which is a mutant replicon bearing an inactivating mutation in the NS5 polymerase region. These results imply that the corresponding residues are indispensable for DENV RNA replication. Replicons bearing the CM3 and CM23 mutants showed a lower replication efficiency (33% and 40%, respectively), suggesting that the lower virus titer of the CM3 and CM23 mutants might be due to the defects in RNA replication. However, the mutations in the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants, which caused apparent defects in virus production, exhibited only mild effects (63 to 95%) on replicon replication. These results suggest that the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants might have defects in subsequent steps after viral RNA replication. Notably, most of the alanine substitution mutations within pTMS4, pTMS5, pTMS6, and pTMS7 did not affect viral RNA replication. In contrast, all mutants with substitutions within pTMS8 displayed lethal phenotypes, indicating that pTMS8 might be required for RNA replication.

FIG 4.

Replication activity of various DENV2 reporter replicons containing NS2A mutations. (A) Schematic representation of the DNA-launched DENV2 reporter replicon pCMV-DV2Rep (used as a reference), which was used in a transient replicon assay. Transcriptional expression of replicon RNA is under the control of the CMVmin promoter, and the 3′ terminus of the transcript is processed by HDV ribozyme sequences. The 5′ UTR (left black line), the N-terminal 102 amino acids of the C protein (C102), the Renilla luciferase gene (Rluc), the FMDV2A cleavage site (black box), a neomycin resistance gene (Neo), an encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosome entry site (IRES) element (gray box), the C-terminal 24 amino acids of E (E24), the entire NS protein regions (NS1 to NS5), the 3′ UTR (right black line), the HDV ribozyme sequence, and the SV40 poly(A) signal sequence are indicated. (B) Effects of NS2A mutations on replication efficiency. BHK21 cells were transfected with WT or NS2A mutant replicon plasmids. At 24 h and 72 h posttransfection, the luciferase activity of the transfected cells was measured. Replication efficiency was calculated by determination of the ratio of luciferase activity obtained at 72 h to the value obtained at 24 h posttransfection and compared with that of the WT replicon. The numbers above the bars represent the percentages of luciferase activity relative to the activity of the WT replicon (which was considered to be 100%), and the error bars represent the SEMs from three independent experiments.

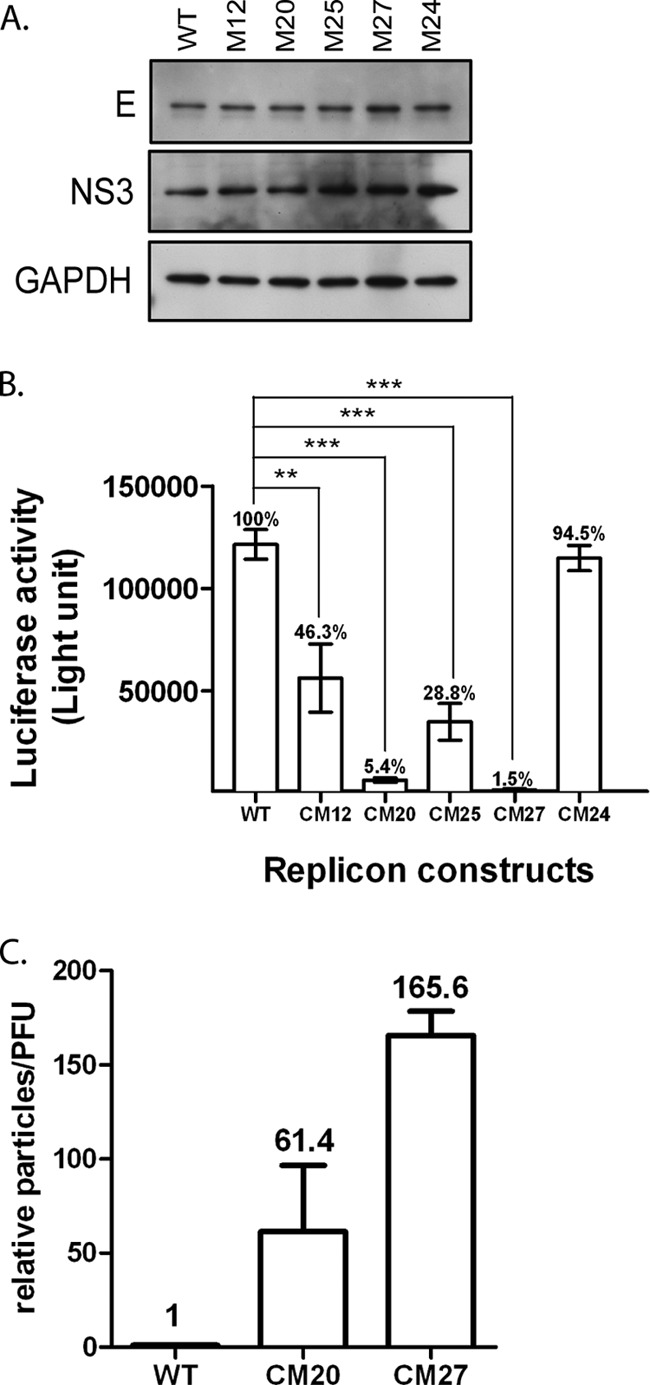

CM20 and CM27 mutants (which have mutations within pTMS7) mainly exhibited a defective phenotype in the production of VLPs.

To determine whether the defects of the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants were in genome packaging and/or virus secretion, replicons bearing NS2A mutations were packaged into virus-like particles (VLPs) by supplying the structural protein of DENV in trans. BHK21 cells were first transfected with pSCA-DENV2-CprME, which was derived from a Semliki forest virus (SFV) vector (37), to express the DENV2 C, prM, and E proteins. At 24 h posttransfection, the transfected cells were subjected to a second round of transfection with WT or NS2A mutant replicon plasmids and pTET-OFF. The culture supernatants from the transfected cells were collected at 48 h after the second transfection and used to infect naive HEK-293 cells. The transfection efficiency was monitored by detecting the expression of the DENV2 E and NS3 proteins in the transfected cells (Fig. 5A). To evaluate the amounts of VLPs released into the culture supernatants, HEK-293 cells were infected with equal volumes of culture supernatants from cells packaging the WT or NS2A mutant. Luciferase activity in the infected cells was measured at 72 h postinfection (Fig. 5B). The CM24 mutant was used as a positive control, as the virus production efficiency of CM24 was similar to that of the WT, and the replicon replication of the CM24 mutant was comparable to that of the CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants. As expected, the packaging efficiency of the CM24 replicon was also similar to the packaging efficiency of the WT replicon. In contrast, compared to the luciferase activity of the WT, the luciferase activities dropped dramatically in cells infected with VLPs collected from cells packaging CM20 and CM27. A moderate decrease in the luciferase activities in cells infected by VLPs collected from cells packaging CM12 and CM25 was also observed. Studies were also performed to measure the relative ratio of noninfectious to infectious particles derived from the WT and CM20 and CM27 mutants by ELISA. The results showed that the CM20 and CM27 mutants had a much higher ratio (61.4- and 165.6-fold, respectively) of the number of particles/number of PFU than the WT (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these data indicate that the mutations in the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants might have exerted some inhibitory effects on the later stage of the virus life cycle, such as virus assembly and/or secretion. Additionally, the mutations within the CM20 and CM27 mutants did not appear to affect replicon replication, while prominent defects in virus assembly and secretion were observed.

FIG 5.

Effects of the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants on the assembly of VLPs. (A) Levels of DENV2 envelope and NS3 expression in transfected cells. BHK21 clone 13 cells were first transfected with the pSCA-DENV2-CprME plasmid. At 24 h posttransfection, the transfected cells were subjected to a second round of transfection with the WT or NS2A mutant replicon plasmid. Culture supernatants were harvested at 48 h following the second transfection, and the cell lysates of the transfected cells were assayed for viral envelope and NS3 protein by Western blotting. (B) Infectious titers of VLPs in the culture supernatants of the transfected cells. Culture supernatants containing VLPs prepared from the transfected cells were used to infect naive HEK-293 cells. At 72 h postinfection, the luciferase activity of the infected cells was assessed. The numbers above the bars represent the percentages of luciferase activity relative to the activity of WT VLP-infected cells (which was considered to be 100%).The error bars represent the SEMs from three independent experiments (n = 3). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (C) CM20 and CM27 mutants display a phenotype with a higher ratio of the number of particles/number of PFU than the WT. HEK-293 cells were transfected with WT or CM20 or CM27 mutant plasmids. At 5 days posttransfection, the supernatants prepared from the transfected cells were harvested. Virus particle production and the viral titers of each sample were determined by plaque-forming assay and antigen-capture ELISA, respectively. Relative activity according to the ratio of the number of particles/number of PFU was calculated by determination of the ratio between the OD at 450 nm and the number of PFU of particles derived from the CM20 or CM27 mutant and compared to the ratio derived from the WT virus. The ratio of the number of particles/number of PFU of the WT virus was defined as 1. The numbers above the bars represent the average value for each mutant virus, and the error bars represent the SEMs from three independent experiments.

Revertant viruses revealed the compensatory mutation NS2A-L181F, which restored the infectivity of the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutant viruses.

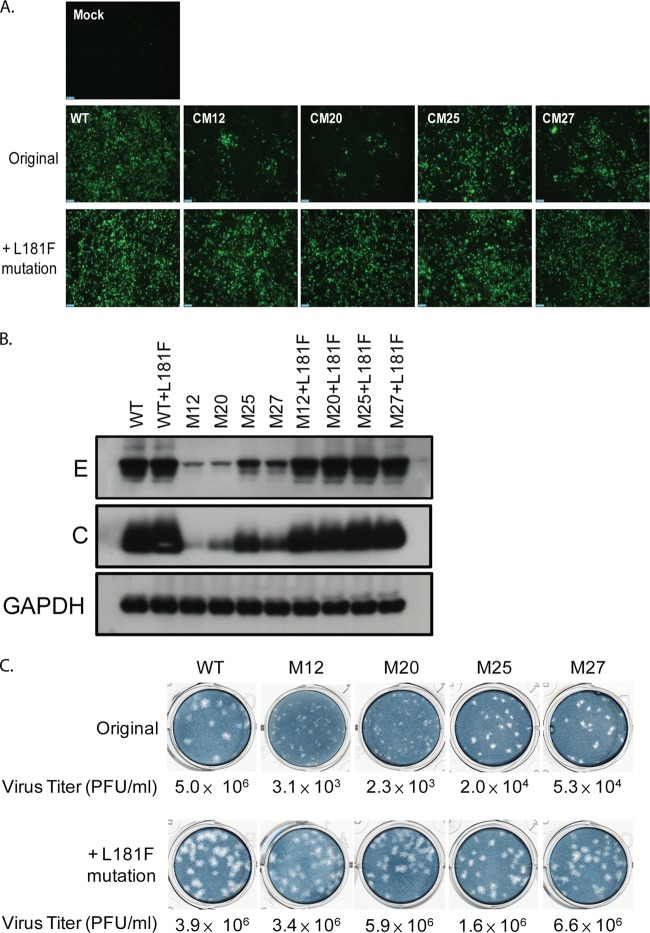

To further investigate the intra- and intermolecular interactions of the NS2A protein, compensatory mutations were identified by continuous passaging of NS2A mutant viruses in HEK-293 cells. The CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants were selected for continuous passaging, as these mutants have a relatively unapparent cytopathic effect (CPE) compared to the CPEs of the other mutants and lower levels of virus production (approximately 103 to 104 PFU/ml) than the other mutants. Thus, revertant viruses could be identified by observation of a CPE or virus titration. After 3 to 5 passages of transfected cells, a CPE was observed in cells transfected with the CM12, CM20, CM25, or CM27 mutant. A plaque-forming assay also showed a 100- to 1,000-fold increase in the virus titer compared to that for the respective original NS2A mutants. To determine the genetic basis of these revertant viruses, their NS2A genes were amplified and sequenced. Surprisingly, a common compensatory mutation was found in all revertant viruses that still maintained the original alanine substitution mutation sites. A cytosine at nucleotide position 4018 of the viral genome was converted to thymidine, resulting in a missense mutation at position 181 of the NS2A protein from leucine to phenylalanine (L181F). To confirm that NS2A-L181F was a true compensatory mutation, CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants bearing NS2A-L181F were generated and characterized. As shown in Fig. 6A, introduction of NS2A-L181F could restore the spreading efficiency of all mutant viruses. Likewise, intracellular expression of the DENV C and E proteins in the cells transfected with NS2A mutant plasmids carrying NS2A-L181F mutations was also restored to a level comparable to that in cells transfected with the WT (Fig. 6B). Next, the effect of NS2A-L181F on virus production and the plaque morphology of the NS2A mutant viruses was monitored. The results presented in Fig. 6C indicate that all mutants containing the NS2A-L181F mutation were profoundly rescued in virus production, and virus titers were enhanced up to 1,000-fold. The smaller plaque sizes observed in the NS2A mutant viruses were restored by the NS2A-L181F mutation to sizes similar to those of the plaques of WT viruses (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that the NS2A-L181F mutation could rescue the defects in virus infectivity, viral structural protein expression, and infectious virus production of the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutant viruses. Furthermore, the NS2A-L181F mutation was located in pTMS7, and the mutations in the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants were located in pTMS6 and pTMS7, suggesting that pTMS7 might interact with pTMS6.

FIG 6.

The NS2A-L181F reversion mutation fully rescues the defect of NS2A mutant viruses in virus infectivity, viral structural protein expression, and infectious virus production. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of HEK-293 cells transfected with WT, NS2A mutant, or revertant plasmids. Monoclonal antibody against the DENV2 prM antigen was used to detect the transfected cells by IFA at 5 days posttransfection. (B) Western blot analyses of HEK-293 cells transfected with WT, NS2A mutant, or revertant plasmids using anti-DENV envelope (4G2) and anti-DENV core (6F3.1) antibodies. (C) Plaque morphology and titers of WT, NS2A mutant, and revertant viruses. BHK21 clone 15 cells were infected with the supernatants harvested from HEK-293 cells transfected with WT, NS2A mutant, or revertant plasmids at 5 days posttransfection. At day 6 postinfection, the infected cells were overlaid with methylcellulose and stained with naphthol blue-black solution.

The NS2A-L181F mutation within pTMS7 rescues the infectivity of several NS2A mutants with mutations within pTMS4 to pTMS8 causing severe defects.

Our previous results showed that NS2A-L181F is a compensatory mutation for CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants. It would be interesting to study whether the NS2A-L181F mutation could rescue the defects in other NS2A mutant viruses. The NS2A-L181F mutation was introduced into the NS2A mutant viruses with moderate defects in RNA replication, such as CM3 and CM23, as well as the mutant viruses with lethal phenotypes, such as CM2, CM6, CM8, CM9, CM13, CM17, CM28, CM29, CM30, CM31, CM32, CM33, CM34, and CM35. As shown in Fig. 7A, introduction of the NS2A-L181F mutation could not rescue the defect in mutant viruses CM6, CM8, CM17, CM28, CM29, CM30, CM33, CM34, and CM35, as determined by IFA. In contrast, however, the defect in mutant viruses CM2, CM3, CM13, CM23, CM31, and CM32 could be completely rescued by the NS2A-L181F mutation, as shown by restoration of the virus spreading capability, and the defect in CM9 was partially rescued. Similarly, intracellular expression of the DENV C and E proteins from the CM2, CM3, CM9, CM13, CM23, CM31, and CM32 mutants was also increased compared to that of the proteins from the respective original NS2A mutants (Fig. 7B).The virus titer and plaque size of the CM2, CM3, CM13, CM23, CM31, and CM32 mutants harboring the NS2A-L181F mutation were comparable to those of the WT (Fig. 7C). These observations indicate that NS2A-L181F could greatly rescue the defects in virus infectivity, viral structural protein expression, and infectious virus production of the CM2, CM3, CM13, CM23, CM31, and CM32 mutant viruses. Additionally, NS2A-L181F (within pTMS7) could rescue the defects of the NS2A mutants with mutations located in pTMS4, pTMS6, pTMS7, and pTMS8, suggesting that the interactions between these pTMSs are essential for the virus life cycle.

FIG 7.

The NS2A-L181F mutation rescues the replication defect in virus infectivity, viral structural protein expression, and infectious virus production of several NS2A mutant viruses. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of HEK-293 cells transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids. Monoclonal antibody against the DENV2 prM antigen was used to detect the transfected cells by IFA at 5 days posttransfection. (B) Western blot analysis of HEK-293 cells transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids using anti-DENV envelope (4G2) and anti-DENV core (6F3.1) antibodies. (C) Plaque morphology and virus titer of the WT and NS2A mutant viruses. BHK21 clone 15 cells were infected with WT and NS2A mutant viruses collected from the supernatants of HEK-293 cells transfected with WT or NS2A mutant plasmids at 5 days posttransfection. At day 6 postinfection, the infected cells were overlaid with methylcellulose and stained with naphthol blue-black solution. ND, not detectable.

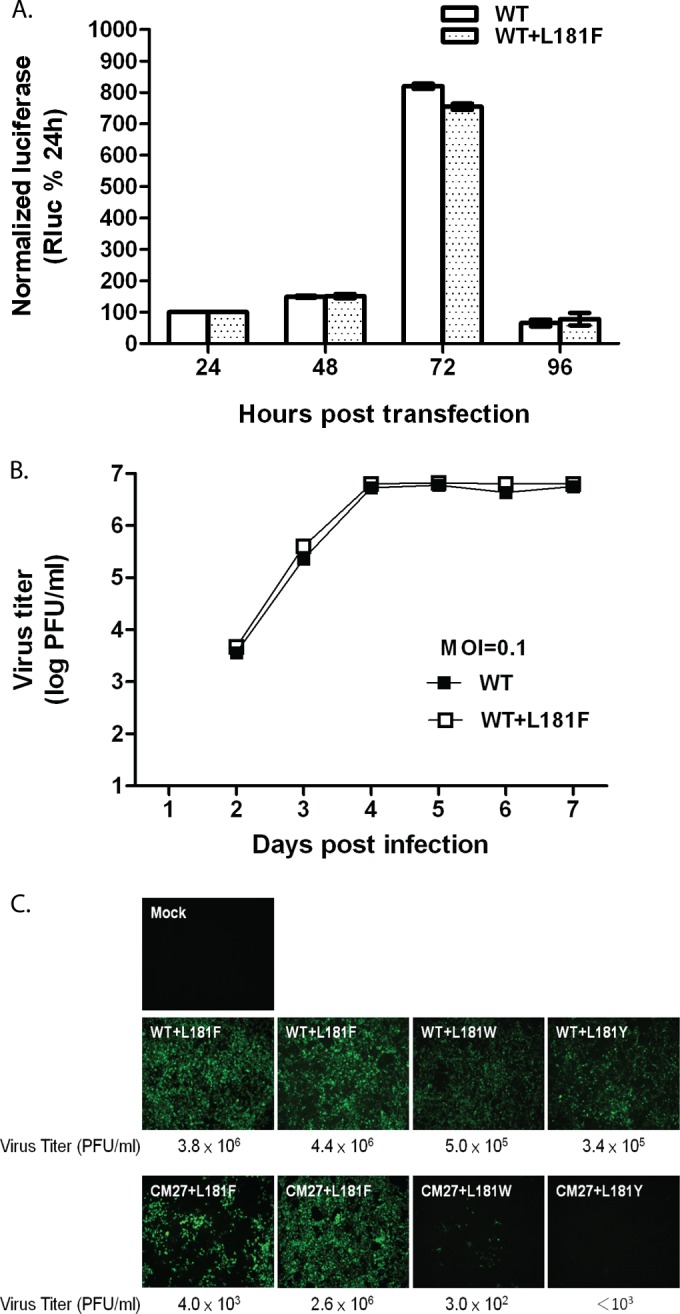

The NS2A-L181F mutation has no apparent effect on viral RNA replication or virus infectivity.

The results thus far indicate that the NS2A-L181F mutation can rescue the defects in virus spreading and production of NS2A mutant viruses. Thus, it would be interesting to study whether the L181F mutation rescues the defects in NS2A mutant viruses via enhancing viral RNA replication. To characterize the effect of the NS2A-L181F mutation introduced into the DENV2 replicons on RNA replication, luciferase assays were performed at the time points indicated below by transfecting BHK21 cells with replicon plasmids carrying the genomes of WT viruses or WT viruses bearing the NS2A-L181F mutation. As shown in Fig. 8A, the levels of Rluc activity peaked at 72 h posttransfection, and the replication efficiencies of WT replicons and WT replicons bearing the NS2A-L181F mutation were indistinguishable. To further evaluate the effect of the NS2A-L181F mutation introduced into the DENV2 genome on DENV2 growth, the growth kinetics of WT viruses bearing the NS2A-L181F mutation in BHK21 cells were analyzed and compared to the growth kinetics of WT viruses. BHK21 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 with viruses harvested from HEK-293 cells transfected with plasmids carrying infectious clones of WT viruses or WT viruses bearing the NS2A-L181F mutation. The supernatants of the infected BHK21 cells were harvested daily, and the titers of the viruses were subsequently determined. The growth kinetics of WT viruses and WT viruses bearing the NS2A-L181F mutation were indistinguishable in BHK21 cells (Fig. 8B). As phenylalanine is an aromatic amino acid, we decided to study whether replacement of NS2A-L181 with other aromatic amino acids could rescue the virus mutants with defective NS2A. Replacements of tryptophan (L181W) and tyrosine (L181Y) were made at L181 of NS2A in the plasmid carrying the CM27 mutant genome for evaluation by IFA and plaque-forming assays (Fig. 8C). WT viruses containing the NS2A-L181F mutation displayed a wild-type phenotype, and WT viruses containing the NS2A-L181W or -L181Y mutation exhibited slight defects in virus spreading and virus yield. The NS2A-L181F mutation could restore the activity of the CM27 mutant virus. In contrast, the NS2A-L181W or -L181Y mutations could not rescue the defect in the CM27 mutant virus. Overall, these results suggest that the NS2A-L181F mutation does not apparently enhance RNA replication or virus yield, and replacement of NS2A-L181 with other aromatic residues could not restore the activity of defective CM27 mutant virus.

FIG 8.

The L181F mutation does not affect virus production or RNA replication, and replacement of L181 with other aromatic amino acids could not rescue the defect of the CM27 mutant virus. (A) Replication efficiency of WT replicons and WT replicons bearing the L181F mutation. The plasmids were transiently transfected into BHK21 cells, and the luciferase activity was monitored at the indicated time points and normalized to the results from 24 h posttransfection. The mean values and SEMs from three independent experiments are plotted. (B) Growth kinetics of WT viruses and WT viruses bearing the L181F mutation. BHK21 cells were infected with WT virus or with WT virus carrying the L181F mutation at an MOI of 0.1. Virus samples from the medium of infected BHK21 cells were harvested daily, and the viral titer in BHK21 cells was determined for each sample. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis and plaque-forming assay of cells transfected with WT or CM27 mutant plasmids containing the L181 substitution. Monoclonal antibody against the DENV2 prM antigen was used to detect the transfected cells by IFA at 5 days posttransfection.

DISCUSSION

In this study, a series of alanine substitution mutations was introduced into the C-terminal half (pTMS4 to pTMS8) of DENV2 NS2A to study the functions of NS2A during the virus life cycle. Functional analysis showed that all NS2A mutations within pTMS8 and several NS2A mutations within pTMS4, pTMS5, and pTMS6 abolished viral RNA replication and resulted in a lethal phenotype. Unlike the mutations in pTMS4, pTMS5, pTMS6, and pTMS8, the NS2A mutations within pTMS7 did not severely affect RNA replication, and several NS2A mutations within pTMS7 greatly affected virus assembly and secretion. The characterization of revertant viruses derived from NS2A mutants with mutations within pTMS7 showed that a compensatory mutation (leucine to phenylalanine) occurred at position 181 within pTMS7. NS2A-L181F greatly rescued most of the RNA replication-defective or virus assembly- and secretion-defective NS2A mutants with mutations within several integral transmembrane segments (pTMS4, pTMS6, pTMS7, and pTMS8) but not pTMS5, a membrane-associated segment. These findings suggest that the C terminus of DENV2 NS2A is critical for viral RNA synthesis as well as virus assembly and secretion. The genetics results derived from revertant analyses implicated a possible complicated interaction between pTMS7 and pTMS4, pTMS6, or pTMS8 of NS2A.

Thirty-five DENV NS2A mutants could be classified into three groups on the basis of their phenotypes, e.g., their virus infectivity, infectious virus production, and RNA replication phenotypes (Fig. 2 and 4B and Table 1). The first group (15 NS2A mutants), i.e., CM1, CM4, CM5, CM7, CM10, CM11, CM14, CM15, CM16, CM18, CM19, CM21, CM22, CM24, and CM26, displayed a wild-type-like phenotype. The second group (14 NS2A mutants), i.e., CM2, CM6, CM8, CM9, CM13, CM17, CM28, CM29, CM30, CM31, CM32, CM33, CM34, and CM35, displayed severe defects in RNA replication, resulting in lethal phenotypes in virus production, indicating that the amino acid residues of the lethal mutants are required for RNA replication. The third group, which included CM3, CM12, CM20, CM23, CM25, and CM27, exhibited a mild to moderate (100- to 1,000-fold) reduction in virus titer resulting from the defect in RNA replication and/or virus assembly and secretion. Overall, these results indicate that the DENV NS2A protein plays crucial roles in both RNA replication and virus assembly and secretion. Our results are consistent with those of a previous study of flavivirus NS2A showing that NS2A is involved in RNA replication (14, 17, 40) and virus assembly and secretion (17–19, 22) in KUNV, YFV, and DENV2. In the YFV studies, an NS2A mutant bearing a K190S mutation (corresponding to residue 188 in DENV2 NS2A) displayed an assembly-deficient phenotype (18).

In general, 15 (∼44%) out of 35 NS2A mutants with mutations within the C-terminal half of NS2A displayed a wild-type phenotype (Table 1 and Fig. 4B). In contrast, triple alanine scanning mutations introduced into the other DENV nonstructural proteins, NS4A and NS4B, almost completely abolished (by >90%) virus infectivity and resulted in a severe to lethal phenotype due to severe defects in RNA replication (data not shown). The phenomenon is likely correlated with the less conserved nature of the amino acid residues of DENV NS2A compared to that of other well-conserved DENV nonstructural proteins, e.g., NS4A and NS4B (41). Notably, all the mutations within the majority of the 14 NS2A mutants with lethal mutations are located at the well-conserved amino acid residues of NS2A in DENV1 to DENV4 (Fig. 1B). These well-conserved residues have been proposed to be essential for RNA replication. In agreement with this observation, the sequence alignment of the amino acid residues of the nonstructural proteins among DENV2, KUNV, YFV, and JEV revealed that NS1, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5 were conserved (33, 14, 40, 22, 15, and 51% identity, respectively), while NS2A was the least conserved (8% identity) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Similarly, strong conservation in NS1, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5 (61, 42, 67, 53, 73, and 67% identity, respectively) was observed among the four dengue virus serotypes, and NS2A was the least conserved (18% identify). Sequence alignment of the C-terminal half (amino acids 109 to 218) of the NS2A protein among the four dengue virus serotypes revealed that some residues are well conserved, including P117, G130, L134, K135, W165, L173, P179, K188, and W191 (Fig. 1B). NS2A mutants bearing alanine substitution mutations in these well-conserved residues and their nearby residues, e.g., the CM3, CM8, CM9, CM20, CM23, CM25, CM34, and CM35 mutants, displayed either severe defective or lethal phenotypes (Fig. 2 and 4B). Among these NS2A mutants, the CM3, CM8, CM9, CM23, CM34, and CM35 mutants displayed severe defects in RNA replication, which suggests that P117, G130, L134, K135, L173, K188, and W191 may be required for RNA replication among the four dengue virus serotypes. The CM20 mutant exhibited severe defects in virus assembly and release, but no apparent effect of the mutation on RNA replication was found, indicating that W165 might be important for virus assembly and release among the four dengue virus serotypes.

Notably, all NS2A mutants with mutations within pTMS8 displayed a lethal phenotype due to impairment of RNA replication (Table 1 and Fig. 4B), indicating that the residues within pTMS8 are indispensable to viral RNA replication. Why all of the amino acid residues within pTMS8 are so susceptible to mutagenesis and essential for RNA replication compared to the findings for the residues within pTMS4 to pTMS7 remains unclear. We speculate that the mutations within pTMS8 may greatly affect the conformation of pTMS8, which is next to the site of NS2A-NS2B cleavage by the NS3/NS2B protease, which in turn abolishes the efficient cleavage of NS2A-NS2B and disables the initiation of viral RNA replication. Alternatively, the mutations within NS2A may affect NS1-NS2A cleavage, which was reported previously (20, 21). However, the scenario was not supported by the results that the lethal mutations within CM2 (pTMS4), CM13 (pTMS6), and CM31 (pTMS8) did not impact the cleavage of NS1-NS2A (data not shown). Another possibility is that the mutations within pTMS8 may interrupt the interaction of the NS2A protein with other viral proteins in the replication complex, in turn impairing the function of the replication complex. In contrast, the mutations in mutants CM20 to CM27 within pTMS7 of NS2A resulted in no lethal phenotype. In general, the alanine substitutions within pTMS7 caused different degrees of defects in virus assembly and secretion but no apparent defect in viral RNA replication (Fig. 5). The study of the relative ratio of noninfectious to infectious particles derived from the WT and the CM20 and CM27 mutants indicated that the CM20 and CM27 mutants have higher ratios (61.4- and 165.6-fold, respectively) of the number of particles/number of PFU than the WT (Fig. 5C), also implying an assembly- and secretion-defective phenotype. These results suggest that pTMS7 may be an integral membrane segment primarily responsible for virus assembly and secretion.

One consensus reversion mutation was identified by characterizing revertant viruses derived from the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants (Fig. 6). Notably, all of these revertant viruses carry a spontaneous second-site compensatory mutation, in which a C is changed to a T at nucleotide position 4018 of the viral genome, resulting in a missense mutation at position 181 of the NS2A protein from leucine (CTC) to phenylalanine (TTC) (NS2A-L181F). To reduce the occurrence of the NS2A-L181F reversion mutation and identify more putative compensatory mutations derived from CM12, CM20, CM15, and CM27, the C nucleotide at position 4020 of the viral genome was changed to G (CTG). Surprisingly, the compensatory mutation NS2A-L181F (TTC) was again identified from these subsequent revertant viruses. This phenomenon clearly suggests that the L181F mutation is a dominant reversion mutation. As codons 180 to 182 of DENV2 NS2A are all leucine residues and only NS2A-L181F was identified from the revertant viruses derived from the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants, the question of whether L180F or L182F can rescue the defect of the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants was raised. Unfortunately, the introduction of the L180F or L182F mutation into the DENV2 genome resulted in a lethal phenotype, which is consistent with the fact that only the L181F mutation was found from isolated revertant viruses. Another question regarding whether L181F enhances RNA replication and/or virus assembly, thus rescuing the defect of the NS2A mutants, was also raised. No apparent difference in the kinetics of virus spreading and replicon activity was found between the WT and L181F virus or replicon (Fig. 8A and B), suggesting that the rescue of the defects in the NS2A mutant virus by L181F possibly does not result from the enhancement of RNA replication and/or virus assembly. The failure of L181W or L181Y to rescue the CM27 mutants strongly indicated that only phenylalanine and not the other aromatic amino acids, tyrosine or tryptophan, corrects the defect caused by the mutations within pTMS4, pTMS6, pTMS7, and pTMS8. These results suggest that the NS2A-L181F reversion mutation is a selective hot spot mutation rescuing the defect of many NS2A mutants, although the detailed mechanism is not clear yet. The NS2A-L181F reversion mutation (located at pTMS7) rescued the phenotype of virus assembly and secretion defects in viral spreading, virus titer, and plaque size of the CM12, CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants (Fig. 6). The CM12 and CM25 mutants showed minor defects in both RNA replication and virus assembly and secretion, whereas the CM20 and CM27 mutants displayed normal RNA replication but severe defects in virus assembly and secretion, suggesting that the NS2A-L181F reversion mutation restores the activity of NS2A in virus assembly and secretion and enhances virus production. As the mutations of the CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants are also located at pTMS7, the L181F reversion mutation within pTMS7 presumably corrected the structural alteration caused by the mutations of the CM20, CM25, and CM27 mutants in the same transmembrane segment, which subsequently rescued virus infectivity. The great restoration of virus spreading activity of the severely RNA replication-defective CM2, CM3, CM13, CM31, and CM32 mutants (pTMS4, pTMS6, and pTMS8) by L181F raised the possibility of a functional relationship between pTMS7 and pTMS4, pTMS6, or pTMS8, possibly through restoration of the interaction between pTMS7 and pTMS4, pTMS6, or pTMS8. These observations also suggest that the NS2A-L181F reversion mutation could restore the activity of NS2A in both RNA replication and virus assembly and secretion. The failure of the L181F mutation to greatly restore the infectivity of the replication-defective CM6, CM8, and CM9 mutants, whose mutations are located in pTMS5, implicates either no interaction between pTMS7 and pTMS5 or an inability to restore the defect caused by the mutations in the CM6, CM8, and CM9 mutants. In agreement with our results, an intramolecular interaction between NS2A pTMSs was reported in a study of KUNV showing that the compensatory mutation T149P (corresponding to residue C154 within pTMS6 of DENV NS2A) rescues the defect in virus assembly and enhances virus production in an NS2A mutant bearing an I59N mutation, within a loop between pTMS2 and pTMS3 (19), indicating an interaction between codons 59 and 149 of KUNV NS2A. In addition to the intramolecular interaction in DENV (or KUNV) NS2A, the intermolecular interaction between YFV NS2A residue K190S (corresponding to residue 188 within pTMS8 of DENV2 NS2A) and NS3 D343, located at the helicase domain, was shown to be essential for YFV assembly and release (18). The failure of several of our attempts to search for other reversion mutations outside the NS2A gene may be due to the dominant reversion mutation, L181F, found in the entire selection of revertant viruses. Thus, further studies are needed to investigate how the intramolecular interaction within NS2A and the intermolecular interaction between NS2A and other nonstructural viral proteins modulate RNA replication and/or virus assembly and secretion. Thus, it will be interesting to unravel the exact mechanism of the complex interplay between the NS2A-L181F reversion mutation and other residues or proteins.

The NS2A-L181F reversion mutation specifically rescued the phenotypes of certain NS2A mutants with lethal mutations, e.g., the CM2, CM3, CM13, CM31, and CM32 mutants, causing defects in viral spreading, virus titer, and the plaque size of virus replication and restored them to nearly wild-type or wild-type phenotypes. NS2A-L181F was also shown to almost fully restore the RNA replication of CM13, CM31, and CM32 mutant replicons when the L181F mutation was introduced into CM13, CM31, and CM32 mutant replicon plasmids (data not shown). However, the NS2A-L181F reversion mutation failed to restore the virus replication of the other lethal NS2A mutants, i.e., the CM6, CM8, CM17, CM28, CM29, CM30, CM33, CM34, and CM35 mutants (Fig. 7). The phenomenon raises the question of how the L181F reversion mutation selectively rescued some of the lethal mutants. According to the topology of NS2A, the L181 residue (pTMS7) and the positions of the mutations within the CM2, CM3, CM13, CM31, and CM32 mutants are all predicted to be located in the proximity of the integral transmembrane and close to the side of the ER lumen (data not shown). In contrast, the positions of the alanine substitution mutations within the CM6, CM8, CM17, CM28, CM29, CM30, CM33, CM34, and CM35 mutants are located either in membrane-associated segments (pTMS5) or in the integral transmembrane region on the cytosolic side. It is speculated that L181F's selective rescue of certain lethal NS2A mutations may be due to the position of the L181 residue close to the side of the ER lumen, which can restore the lethal mutations within the other pTMSs, pTMS4, pTMS6, and pTMS8, close to the side of the ER lumen. The selective rescue of lethal NS2A mutations by L181F further supports the revertant genetics results, indicating that the integral transmembrane segment pTMS7 may closely interact with the other integral transmembrane segments, pTMS4, pTMS6, and pTMS8, although the X-ray structure of DENV NS2A is not available. Very little is known about the detailed mechanism of NS2A involvement in RNA replication and virus assembly. Further studies are needed to investigate how NS2A facilitates virus assembly and/or anchoring of the viral replication complexes on the ER membrane.

In summary, our results presented here confirm that the C-terminal half of DENV2 NS2A is involved in both RNA replication and virus assembly and secretion. The amino acid residues or pTMSs essential for NS2A functions were also identified. Three classes of NS2A mutants with distinct phenotypes from our study and previous studies are summarized in Table 2. The amino acid residues within NS2A responsible for various phenotypes were indicated. Our revertant genetics results revealed that the NS2A-L181F reversion mutation can rescue many RNA replication-defective and virus assembly- and secretion-defective NS2A mutants, which provides useful information regarding the intramolecular interactions among several transmembrane segments of the NS2A protein. These findings will help us investigate the role of NS2A in both viral RNA replication and virus assembly and secretion and broaden our understanding of flavivirus replication and pathogenesis. This knowledge will also be applied to anti-DENV vaccine and drug development.

TABLE 2.

Summary of flavivirus NS2A mutants with distinct phenotypes

| Class | NS2A mutants (reference) | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| I | DENV2 CM1, CM4, CM5, CM7, CM10, CM11, CM14, CM15, CM16, CM18, CM19, CM21, CM22, CM24, and CM26 (our study) and DENV2 R24A, R26A, R46A, D52A, G69A, F81A, T97A, K99A, and K135A (21) | Partial or no effect on virus production |

| II | DENV2 CM2, CM6, CM8, CM9, CM13, CM17, CM28, CM29, CM30, CM31, CM32, CM33, CM34, and CM35 (our study) and DENV2 D125A and G200A (21) | Severe defect in RNA replication |

| III | DENV2 CM20 and CM27 (our study); DENV2 G11A, E20A, E100A, Q187A, and K188A (21); R84A (17); YFV K190S (18); and KUNV I59N (19, 22) | Moderate to severe defect in virus assembly and secretion |

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Rod Bremner for providing the pSCA1 plasmid. We also appreciate Su-Ying Wu's helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Science Council of the Republic of China (grant no. NSC 102-2325-B-400-006).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.03011-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindenbach B, Murray C, Thiel H, Rice C. 2013. Flaviviridae. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed (electronic) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2013. Flaviviruses, p 747–798. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed, vol 1 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simmons CP, Farrar JJ, van Vinh Chau N, Wills B. 2012. Dengue. N Engl J Med 366:1423–1432. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1110265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzman MG, Kouri G. 2002. Dengue: an update. Lancet Infect Dis 2:33–42. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman MG, Kouri G. 2004. Dengue diagnosis, advances and challenges. Int J Infect Dis 8:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2003.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinheiro FP, Corber SJ. 1997. Global situation of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever, and its emergence in the Americas. World Health Stat Q 50:161–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gubler DJ. 1989. Aedes aegypti and Aedes aegypti-borne disease control in the 1990s: top down or bottom up. Charles Franklin Craig Lecture. Am J Trop Med Hyg 40:571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halstead SB. 1980. Dengue haemorrhagic fever—a public health problem and a field for research. Bull World Health Organ 58:1–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinheiro FP. 1989. Dengue in the Americas. 1980-1987. Epidemiol Bull 10:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinney RM, Butrapet S, Chang GJ, Tsuchiya KR, Roehrig JT, Bhamarapravati N, Gubler DJ. 1997. Construction of infectious cDNA clones for dengue 2 virus: strain 16681 and its attenuated vaccine derivative, strain PDK-53. Virology 230:300–308. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chambers TJ, Hahn CS, Galler R, Rice CM. 1990. Flavivirus genome organization, expression, and replication. Annu Rev Microbiol 44:649–688. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.003245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falgout B, Pethel M, Zhang YM, Lai CJ. 1991. Both nonstructural proteins NS2B and NS3 are required for the proteolytic processing of dengue virus nonstructural proteins. J Virol 65:2467–2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice CM, Lenches EM, Eddy SR, Shin SJ, Sheets RL, Strauss JH. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of yellow fever virus: implications for flavivirus gene expression and evolution. Science 229:726–733. doi: 10.1126/science.4023707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA, Jones MK, Westaway EG. 1998. Subcellular localization and some biochemical properties of the flavivirus Kunjin nonstructural proteins NS2A and NS4A. Virology 245:203–215. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munoz-Jordan JL, Sanchez-Burgos GG, Laurent-Rolle M, Garcia-Sastre A. 2003. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:14333–14338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335168100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambers TJ, McCourt DW, Rice CM. 1989. Yellow fever virus proteins NS2A, NS2B, and NS4B: identification and partial N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. Virology 169:100–109. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie X, Gayen S, Kang C, Yuan Z, Shi PY. 2013. Membrane topology and function of dengue virus NS2A protein. J Virol 87:4609–4622. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02424-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kummerer BM, Rice CM. 2002. Mutations in the yellow fever virus nonstructural protein NS2A selectively block production of infectious particles. J Virol 76:4773–4784. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4773-4784.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung JY, Pijlman GP, Kondratieva N, Hyde J, Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA. 2008. Role of nonstructural protein NS2A in flavivirus assembly. J Virol 82:4731–4741. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00002-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falgout B, Markoff L. 1995. Evidence that flavivirus NS1-NS2A cleavage is mediated by a membrane-bound host protease in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol 69:7232–7243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie X, Zou J, Puttikhunt C, Yuan Z, Shi PY. 2015. Two distinct sets of NS2A molecules are responsible for dengue virus RNA synthesis and virion assembly. J Virol 89:1298–1313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02882-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu WJ, Chen HB, Khromykh AA. 2003. Molecular and functional analyses of Kunjin virus infectious cDNA clones demonstrate the essential roles for NS2A in virus assembly and for a nonconservative residue in NS3 in RNA replication. J Virol 77:7804–7813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7804-7813.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu WJ, Chen HB, Wang XJ, Huang H, Khromykh AA. 2004. Analysis of adaptive mutations in Kunjin virus replicon RNA reveals a novel role for the flavivirus nonstructural protein NS2A in inhibition of beta interferon promoter-driven transcription. J Virol 78:12225–12235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12225-12235.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu WJ, Wang XJ, Clark DC, Lobigs M, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. 2006. A single amino acid substitution in the West Nile virus nonstructural protein NS2A disables its ability to inhibit alpha/beta interferon induction and attenuates virus virulence in mice. J Virol 80:2396–2404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2396-2404.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu WJ, Wang XJ, Mokhonov VV, Shi PY, Randall R, Khromykh AA. 2005. Inhibition of interferon signaling by the New York 99 strain and Kunjin subtype of West Nile virus involves blockage of STAT1 and STAT2 activation by nonstructural proteins. J Virol 79:1934–1942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1934-1942.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tu YC, Yu CY, Liang JJ, Lin E, Liao CL, Lin YL. 2012. Blocking double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase PKR by Japanese encephalitis virus nonstructural protein 2A. J Virol 86:10347–10358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00525-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang YS, Liao CL, Tsao CH, Chen MC, Liu CI, Chen LK, Lin YL. 1999. Membrane permeabilization by small hydrophobic nonstructural proteins of Japanese encephalitis virus. J Virol 73:6257–6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melian EB, Edmonds JH, Nagasaki TK, Hinzman E, Floden N, Khromykh AA. 2013. West Nile virus NS2A protein facilitates virus-induced apoptosis independently of interferon response. J Gen Virol 94:308–313. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.047076-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miroux B, Walker JE. 1996. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol 260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burke D, Dawson D, Stearns T. 2000. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morens DM, Halstead SB, Repik PM, Putvatana R, Raybourne N. 1985. Simplified plaque reduction neutralization assay for dengue viruses by semimicro methods in BHK-21 cells: comparison of the BHK suspension test with standard plaque reduction neutralization. J Clin Microbiol 22:250–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pu SY, Wu RH, Tsai MH, Yang CC, Chang CM, Yueh A. 2014. A novel approach to propagate flavivirus infectious cDNA clones in bacteria by introducing tandem repeat sequences upstream of virus genome. J Gen Virol 95:1493–1503. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.064915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blight KJ. 2011. Charged residues in hepatitis C virus NS4B are critical for multiple NS4B functions in RNA replication. J Virol 85:8158–8171. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00858-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul D, Romero-Brey I, Gouttenoire J, Stoitsova S, Krijnse-Locker J, Moradpour D, Bartenschlager R. 2011. NS4B self-interaction through conserved C-terminal elements is required for the establishment of functional hepatitis C virus replication complexes. J Virol 85:6963–6976. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00502-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang CC, Hsieh YC, Lee SJ, Wu SH, Liao CL, Tsao CH, Chao YS, Chern JH, Wu CP, Yueh A. 2011. Novel dengue virus-specific NS2B/NS3 protease inhibitor, BP2109, discovered by a high-throughput screening assay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:229–238. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00855-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang CC, Tsai MH, Hu HS, Pu SY, Wu RH, Wu SH, Lin HM, Song JS, Chao YS, Yueh A. 2013. Characterization of an efficient dengue virus replicon for development of assays of discovery of small molecules against dengue virus. Antiviral Res 98:228–241. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiCiommo DP, Bremner R. 1998. Rapid, high level protein production using DNA-based Semliki Forest virus vectors. J Biol Chem 273:18060–18066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufman BM, Summers PL, Dubois DR, Cohen WH, Gentry MK, Timchak RL, Burke DS, Eckels KH. 1989. Monoclonal antibodies for dengue virus prM glycoprotein protect mice against lethal dengue infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 41:576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galula JU, Shen WF, Chuang ST, Chang GJ, Chao DY. 2014. Virus-like particle secretion and genotype-dependent immunogenicity of dengue virus serotype 2 DNA vaccine. J Virol 88:10813–10830. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00810-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossi SL, Fayzulin R, Dewsbury N, Bourne N, Mason PW. 2007. Mutations in West Nile virus nonstructural proteins that facilitate replicon persistence in vitro attenuate virus replication in vitro and in vivo. Virology 364:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haishi S, Tanaka M, Igarashi A. 1990. Comparative amino acid sequences of dengue viruses. Trop Med 32:81–87. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.