ABSTRACT

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, ∼22-nucleotide-long RNAs that regulate gene expression posttranscriptionally. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) encodes 12 pre-miRNAs during latency, and the functional significance of these microRNAs during KSHV infection and their cellular targets have been emerging recently. Using a previously reported microarray profiling analysis, we identified breakpoint cluster region mRNA (Bcr) as a cellular target of the KSHV miRNA miR-K12-6-5p (miR-K6-5). Bcr protein levels were repressed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) upon transfection with miR-K6-5 and during KSHV infection. Luciferase assays wherein the Bcr 3′ untranslated region (UTR) was cloned downstream of a luciferase reporter showed repression in the presence of miR-K6-5, and mutation of one of the two predicted miR-K6-5 binding sites relieved this repression. Furthermore, inhibition or deletion of miR-K6-5 in KSHV-infected cells showed increased Bcr protein levels. Together, these results show that Bcr is a direct target of the KSHV miRNA miR-K6-5. To understand the functional significance of Bcr knockdown in the context of KSHV-associated disease, we hypothesized that the knockdown of Bcr, a negative regulator of Rac1, might enhance Rac1-mediated angiogenesis. We found that HUVECs transfected with miR-K6-5 had increased Rac1-GTP levels and tube formation compared to HUVECs transfected with control miRNAs. Knockdown of Bcr in latently KSHV-infected BCBL-1 cells increased the levels of viral RTA, suggesting that Bcr repression by KSHV might aid lytic reactivation. Together, our results reveal a new function for both KSHV miRNAs and Bcr in KSHV infection and suggest that KSHV miRNAs, in part, promote angiogenesis and lytic reactivation.

IMPORTANCE Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) infection is linked to multiple human cancers and lymphomas. KSHV encodes small nucleic acids (microRNAs) that can repress the expression of specific human genes, the biological functions of which are still emerging. This report uses a variety of approaches to show that a KSHV microRNA represses the expression of the human gene called breakpoint cluster region (Bcr). Repression of Bcr correlated with the activation of a protein previously shown to cause KS-like lesions in mice (Rac1), an increase in KS-associated phenotypes (tube formation in endothelial cells and vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] synthesis), and modification of the life cycle of the virus (lytic replication). Our results suggest that KSHV microRNAs suppress host proteins and contribute to KS-associated pathogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is a gammaherpesvirus that is associated with AIDS-associated KS, primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) (1, 2). KSHV infects primarily cells of endothelial cell or B-cell origin and persists in either a latent phase, during which only a few viral genes are expressed, or a lytic phase, where the full repertoire of viral genes is expressed and infectious virions are released. During latent infection, KSHV also expresses 12 pre-microRNAs (pre-miRNAs) that are processed to yield ∼20 mature miRNAs (3–6). miRNAs are ∼22-nucleotide-long RNAs that typically bind with imperfect complementarity to the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs and cause translational repression and mRNA degradation (7). The KSHV miRNAs are believed to be involved in repressing numerous targets that are involved in immune evasion (MICB) (8), apoptosis (BCLAF1, TWEAKR, and caspase 3) (9–11), lytic reactivation (RTA) (12, 13), angiogenesis (THBS1) (14), transcription repression (BACH1) (15, 16), and cell signaling (p21, IκB, and SMAD5) (17–19).

Previously, we reported a microarray-based expression profiling approach to identify cellular mRNAs that are downregulated in the presence of KSHV miRNAs (11). From this array, we identified BCLAF1 (11), TWEAKR (9), and IRAK1 and MyD88 (20) as cellular targets of KSHV miRNAs. In this report, we identify the breakpoint cluster region (Bcr) mRNA and RacGAP1 as cellular targets of the KSHV miRNA miR-K12-6-5p (miR-K6-5).

Bcr was originally identified as a fusion partner of Bcr-Abl, which is the fusion protein that is associated with most forms of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and acute lymphocytic leukemias (ALLs) (21). Bcr by itself has been suggested to act as a tumor suppressor (22). Bcr interferes with the β-catenin–Tcf4 interaction and is a negative regulator of the Wnt pathway (22, 23). Bcr phosphorylates the Ras effector protein AF-6 and facilitates its interaction with Ras, thereby inhibiting extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation and cellular proliferation (24). The Bcr protein has oligomerization, Ser/Thr kinase (25), and guanosine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) (26, 27) domains. In addition, Bcr contains a C-terminal GTPase activation domain (GAP), with which it inhibits the function of Rac1 (28). Rac1 exists between an active, membrane-bound state (Rac1-GTP) and an inactive, cytoplasmic state (Rac1-GDP) (29). As a Rac1 GAP, Bcr enhances the intrinsic GTPase activity of Rac1 and therefore negatively regulates its function. Rac1 belongs to the Rho family of small GTPases that control cytoskeletal organization, cell motility, and angiogenesis. Deregulated angiogenesis is often observed in many cancers and is a hallmark of KS. KS is a highly vascularized tumor that expresses elevated levels of angiogenic molecules such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (30). VEGF is a key proangiogenic factor and, upon binding to its receptors on the endothelial cell surface, stimulates angiogenesis by recruiting Rac1. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of Rac1 reduces VEGF-induced angiogenesis in vitro and tumor progression in mice (31). Aberrant regulation of Rac1 has been observed for many cancers, including KS (32–34).

In this study, we identified Bcr, a negative regulator of Rac1, in the analysis of mRNAs that were downregulated by KSHV miRNAs. Bcr was repressed by miR-K6-5 in B cells and endothelial cells and in the context of de novo KSHV infection. The repression of Bcr by miR-K6-5 caused increases in the levels of Rac1-GTP and VEGF in endothelial cells. Furthermore, the increased Rac1-GTP levels also enhanced tube length in endothelial tube formation assays, and this effect was recapitulated by an siRNA targeting Bcr. Finally, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Bcr in latently infected BCBL-1 cells increased the levels of the viral RTA protein, the key regulator of KSHV lytic reactivation, suggesting a potential advantage of Bcr suppression during KSHV infection. These results together identify a cellular mRNA, Bcr, as a target of the KSHV miRNA miR-K6-5, and we further demonstrate that the virus is able to establish an angiogenic environment and facilitate lytic reactivation as a consequence of this repression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Lonza) were maintained for up to five passages with complete EGM-2 BulletKit (Lonza). The latently KSHV-infected body cavity-based lymphoma cell line (BCBL-1) and the uninfected BJAB B-cell line were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× penicillin-streptomycin, and 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol. 293 cells and SLK cells (35, 36) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1× penicillin-streptomycin. KSHV-infected SLK cells (SLK+K cells) (37) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin-streptomycin, and 10 μg/ml of puromycin. Telomerase-immortalized microvascular endothelial (TIME) cells were grown in vascular cell basal medium with endothelial cell growth kit-VEGF (ATCC), and KSHV-infected TIME cells were grown in medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml of hygromycin B. Inducible TIME (iTIME) cells were a gift from Craig McCormick (Dalhousie University) and were generated by using the Retro-X Tet-Off Advanced inducible expression system (Clontech) (38). Clonal TIME cell lines expressing Tet-Off Advanced transactivator (tTA-Advanced cells) were transduced with retroviral vectors encoding KSHV RTA controlled by a modified Tet-responsive element (TREmod) joined to a minimal cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. The clonal cells resulting from these transductions, dubbed iTIME cells, were cultured in complete vascular cell basal medium (VCBM) supplemented with a VEGF kit (ATCC) containing 500 μg/ml G418, 1 μg/ml puromycin, and 200 ng/ml doxycycline. KSHV-infected cells were grown in 200 ng/ml doxycycline and 25 μg/ml hygromycin B. miRVana miRNA mimics were purchased from Ambion; ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNAs targeting human Bcr, RacGAP1, and the nontargeting pool control were obtained from Thermo Scientific.

Production of mutant KSHVs from inducible SLK cell lines.

Inducible SLK (iSLK) cell lines that harbor either wild-type or mutant KSHVs that lack miR-K12-6 (ΔK6-KSHV cells) were a generous gift from Rolf Renne and were maintained in DMEM containing 1 μg/ml puromycin, 250 μg/ml G418, and 1.2 mg/ml hygromycin B (39, 40). Virus production was induced with DMEM containing 1 μg/ml doxycycline and 1 mM valproate. The iSLK cells were maintained in the induction medium for 4 days to allow virus production, after which KSHV virions released into the culture supernatants were purified and concentrated by using the Vivaflow 50 tangential-flow filtration system (Sartorius Stedim Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For normalization of KSHV infections, viral DNA was extracted by using DNAzol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc.), and KSHV LANA (latency-associated nuclear antigen) levels were measured by using quantitative PCR (qPCR) with the following set of primers: 5′-GTGACCTTGGCGATGACCTA-3′ and 5′-CAGGAGATGGAGAATGAGTA-3′. Infection of TIME cells was performed by using viruses normalized for their LANA DNA. Infected TIME cells were selected on hygromycin B for several weeks, after which Western blotting was performed to analyze differences in protein expression.

miRNA transfections and Western blotting.

For the transfection of miRNAs and siRNAs, 2 × 105 HUVECs were seeded onto 6-well plates overnight. Transfections were performed with 10 nM miRNAs or 16.5 nM siRNAs using Dharmafect (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The transfected cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection (hpt), and their total protein was extracted in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma) containing 1× Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific). For Western blotting, equal amounts of total proteins were electrophoresed by SDS-PAGE, and protein levels were quantified by using a Li-Cor Odyssey infrared imaging system. Primary antibodies against Bcr (catalog number 3902) were obtained from Cell Signaling, Inc. Primary antibodies against RacGAP1 were purchased from Thermo Scientific, Inc. Mouse antiactin primary antibody (catalog number AC-74) was obtained from Sigma. The rabbit anti-RTA antibody was a gift from Don Ganem. Secondary antibodies conjugated to the infrared fluorescing dyes IRDye 800CW and IRDye 680 were obtained from Li-Cor. Changes in protein levels were measured relative to the actin level, and fold changes were obtained relative to values for the respective negative-control RNAs.

3′-UTR reporter assays.

Oligonucleotides used for cloning of the Bcr 3′ UTR were 5′-CTGGAAACCTCTGGCTAATC-3′ and 5′-CAAAAAAGCATCACTTCCG-3′. 293 cells were reverse transfected in 96-well plates by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with 13 nM each KSHV miRNA (or a negative-control miRNA [miR-Neg]) and a luciferase reporter plasmid (pD765-Bcr), which expresses herpes simplex virus TK (HSV-TK) promoter-driven firefly luciferase as an internal control and simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter-driven Renilla luciferase fused to the 3′ UTR of Bcr as the reporter (Protein Expression Laboratory, SIAC, Frederick, MD). A reporter plasmid lacking any 3′ UTR adjacent to the Renilla luciferase served as a control for nonspecific responses of luciferase expression to the KSHV miRNAs. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the pD765-Bcr reporter plasmid by using the QuikChange II kit (Stratagene). The following primers and their reverse complements were used to introduce mutations into the Bcr 3′ UTR: 5′-GTCAGTGGGCAGCTCCTAATGAACCCGCAGCTC-3′ for mut1 and 5′-CTCACTGTTGTATCTTGAATAAACGCTAATGCTTCATCCTGTGG-3′ for mut2. For cloning of the 3′ UTR of RacGAP1, oligonucleotides containing the predicted miR-K6-5 binding sites (underlined in the oligonucleotides below) were annealed and cloned into the pCR8-GW-TOPO vector (Life Technologies). Oligonucleotides for the wild-type (WT) RacGAP1 site were 5′-AGTACAACTCGTATTTATCTCTGATGTGCTGCTGGCTGAA-3′ and 5′-TCAGCCAGCAGCACATCAGAGATAAATACGAGTTGTACTA-3′. The binding site was mutated by using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-AGTACAACTCGTATTTATCTCTGATCACGACGACGCTGAA-3′ and 5′-TCAGCGTCGTCGTGATCAGAGATAAATACGAGTTGTACTA-3′. Upon confirmation by sequencing from the pCR8-GW-TOPO vector, these DNA sequences were cloned downstream of the Renilla luciferase in pDEST-765 by using Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix (Life Technologies) to generate plasmids pDEST-WT-RG1 and pDEST-mut-RG1. Assays were performed by using the Dual-Luciferase reporter system (Promega) at 24 and 48 hpt. The ratio of the activities of renilla luciferase over those of firefly luciferase in each well was used as a measure of total reporter activation. The results shown are averages of data from three independent experiments, assayed in triplicate.

Inhibition of miRNAs in BCBL-1 cells using power-locked nucleic acid inhibitors.

Power-locked nucleic acid inhibitors (power-LNAs) against miR-K12-6-5p (Exiqon), at a total of 50 pmol, were electroporated into 2 × 106 BCBL-1 cells in Nucleofection solution V by using program T-01 of the Nucleofector I instrument, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amaxa, Inc.). Cells were harvested at 48 h postelectroporation, and total protein was extracted in RIPA lysis buffer. Expression levels of the Bcr protein were quantitated relative to actin expression levels, as described above. Changes in protein levels upon LNA electroporation were compared to those of BCBL-1 cells electroporated with the negative-control LNA (NegA).

De novo KSHV infection.

KSHV virions were purified from BCBL-1 cultures 7 days after induction with valproic acid and concentrated by centrifugation. KSHV infection of HUVECs and TIME cells was performed with medium containing 8 μg/ml Polybrene for 6 h at 37°C. Medium was changed every 2 days, and the adherent cells were harvested at 7 or 10 days postinfection (HUVECs) for analysis by Western blotting.

Rac activation assays.

HUVECs were transfected with miRNA mimics as described above. At 5 hpt, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and their medium was replaced with reduced-serum Opti-MEM-1 (Gibco) for 20 h. GTPase activity was induced with 10 ng/ml of VEGF (Peprotech) for 10 min, after which the cells were processed for the measurement of Rac1-GTP levels using a G-LISA Rac1 activation assay kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Cytoskeleton, Inc.).

Endothelial tube formation assays.

HUVECs were transfected with miRNAs or siRNAs as described above. The transfected cells were harvested 48 h later, and a portion of the cells was saved for Western blot analysis. Equal numbers of transfected cells were resuspended in a low-serum medium, EBM2 (basal medium with no supplements added; Lonza), with 10% EGM-2 BulletKit (complete HUVEC medium; Lonza) and plated onto μ-slides for angiogenesis assays (Ibidi, LLC). The slides were coated with the Geltrex reduced growth factor basement membrane matrix (Gibco) for 30 min at 37°C. Equal numbers of transfected HUVECs in low-serum medium were added to each coated well, and tube formation was allowed to proceed for 16 h at 5% CO2 and 37°C. To prepare the cells for imaging, the HUVEC networks were stained with Calcein AM (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature and washed three times with PBS. Images were collected by using a Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) epifluorescence microscope equipped with a 10× Plan-Neofluar (numerical aperture [NA], 0.3) objective lens, a motorized scanning stage, and a CoolSnap ES charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera (Photometrics). The mosaiX module of the Zeiss AxioVision (v. 4.8) image acquisition software was used to collect a series of tile images that covered the entire area of the individual μ-slide wells. The tile images were stitched together to form a single large image maintaining the origin pixel information. The stitched images were exported as 16-bit tiff files, and tube and segment lengths were analyzed by using the “angiogenesis tube formation” algorithm run in MetaMorph (v. 7.7) (Molecular Devices) software. To avoid any bias that might arise while choosing a region of interest for tube length analysis, we analyzed the entire imaged well area for tube length measurements. The fluorescence along the perimeter of the well was considered background and not used for the final image analysis. The results are representative of three independent experiments, and P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from miR-Neg- or miR-K6-5-transfected cells at 48 hpt by using an miRNeasy minikit (Qiagen). A total of 1 μg of the RNA was converted to cDNA by using the High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). The following primers were used for measurement of VEGF mRNA levels: 5′-AGGCCAGCACATAGGAGA-3′ and 5′-ACCGCCTCGGCTTGTCACAT-3′. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA was used as a normalization control. qPCR analysis was performed by using FastStart Universal SYBR green Master (ROX) (Roche Diagnostics GmbH), using the relative quantitation method. TaqMan miRNA assays (Life Technologies, Inc.) were used for the measurement of KSHV miRNA levels in infected TIME cells. For analysis of viral lytic mRNAs, primer pairs for RTA, ORF57, ORF59, and K8 were designed as described previously (41).

Immunofluorescence assay.

TIME cells infected with either WT- or ΔK6-KSHV were grown on Lab-Tek II four-well chamber slides (Thermo Scientific, Inc.). For LANA staining, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized. After blocking, the cells were incubated for 3 h with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against KSHV LANA. Alexa-594-coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were used to visualize LANA under a Zeiss fluorescence microscope, using appropriate filters.

RESULTS

Previously, we reported a microarray profiling analysis for the identification of mRNAs that were downregulated in the presence of KSHV miRNAs in B cells and in the context of KSHV infection of endothelial cells (11). From the array data for BJAB B cells (GEO accession number GSE65148), we identified breakpoint cluster region (Bcr) as an mRNA that was downregulated in the presence of miR-K6-5. Data from two biological replicates showed that Bcr was the 176th most repressed gene out of 14,384 gene probes (1.2% of genes) in the BJAB arrays (−0.43 log2). Bcr mRNA levels were also downregulated in the context of KSHV infection of HUVECs (−0.24 log2).

Bcr is a direct target of KSHV miR-K6-5.

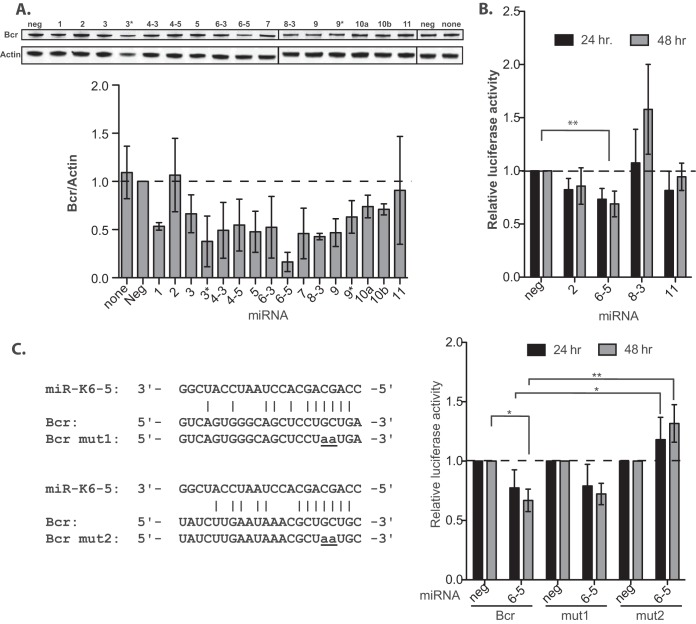

The microarray data showed that miR-K6-5 and de novo KSHV infections repress Bcr at the mRNA level. To ensure that Bcr was also repressed at the protein level, we transfected individual miRNA mimics into primary endothelial cells (HUVECs). At 48 h posttransfection, we performed Western blot analyses on the transfected-cell lysates and normalized the levels of Bcr protein to that of actin (Fig. 1A, top). We observed that several KSHV miRNAs, namely, miR-K1, -K6-5, and -K8, strongly repressed Bcr at the protein level (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the mRNA data, expression miR-K6-5 resulted in almost a 4-fold downregulation of the Bcr protein, compared to the negative-control miRNA or no miRNA.

FIG 1.

Bcr is a direct target of KSHV microRNAs. (A, top) HUVECs were transfected with individual KSHV pre-miRNA mimics, and total cell lysates were harvested for Western blot analysis at 48 hpt. (Bottom) The relative expression level of Bcr was normalized to that of actin. (B) 293 cells were reverse transfected with reporter plasmids wherein the 3′ UTR of Bcr was cloned downstream of the Renilla luciferase along with the indicated KSHV miRNAs. Cells were harvested at 24 or 48 hpt for reporter activity measurements. (C, left) Predicted binding sites for miR-K6-5 in the 3′ UTR of Bcr conforming to either the 7-mer 1A (top) or the 7-mer m8 (bottom) type. These sites were also mutated to eliminate miR-K6-5 binding (mut1 or mut2), for use in luciferase assays to identify the precise miR-K6-5 binding site in the 3′ UTR of Bcr. (Right) Luciferase reporter assays performed in 293 cells using Bcr 3′-UTR mutants mut1 and mut2 to identify the exact miR-K6-5 binding site. * denotes a P value of <0.05, and ** denotes a P value of <0.01.

To validate Bcr as a direct target of KSHV miRNAs, we performed luciferase reporter assays wherein the 3′ UTR of Bcr was cloned downstream of a renilla luciferase reporter (pD765-Bcr). 293 cells were transfected with pD765-Bcr and various KSHV miRNAs, and repression of reporter activity was used as an indicator of miRNA binding to the Bcr 3′ UTR. In the presence of miR-K6-5, there was a statistically significant repression of reporter activity, indicating that miR-K6-5 could bind directly to the 3′ UTR of Bcr (Fig. 1B). The other miRNAs tested (miR-K2, -K8, and -K11) could not repress the luciferase activity, suggesting that the interaction of miR-K6-5 with the 3′ UTR of Bcr was specific.

Using TargetScan (42), we identified two potential miR-K6-5 binding sites, conforming to either a 7-mer 1A or a 7-mer m8 type, in the 3′ UTR of Bcr (Fig. 1C, left). However, TargetScan could not identify any potential binding sites for miR-K1 and -K8 (the miRNAs that also repressed Bcr at the protein level) (Fig. 1A) in the 3′ UTR of Bcr. To confirm that Bcr is a direct target of miR-K6-5, we introduced mutations, “mut1” and “mut2” (Fig. 1C), in the two predicted miR-6-5 binding sites in the 3′ UTR of Bcr. While reporter plasmids bearing the mut1 3′ UTR could still be repressed by miR-K6-5, reporter plasmids bearing the mut2 3′ UTR were not suppressed by miR-K6-5 (Fig. 1C, right). Thus, the mut2 site in the 3′ UTR of Bcr is critical for miR-K6-5-mediated repression of Bcr. Together, these results suggest that Bcr is a direct target of KSHV miR-K6-5.

Bcr is downregulated by miR-K6-5 both in HUVECs and upon de novo KSHV infection.

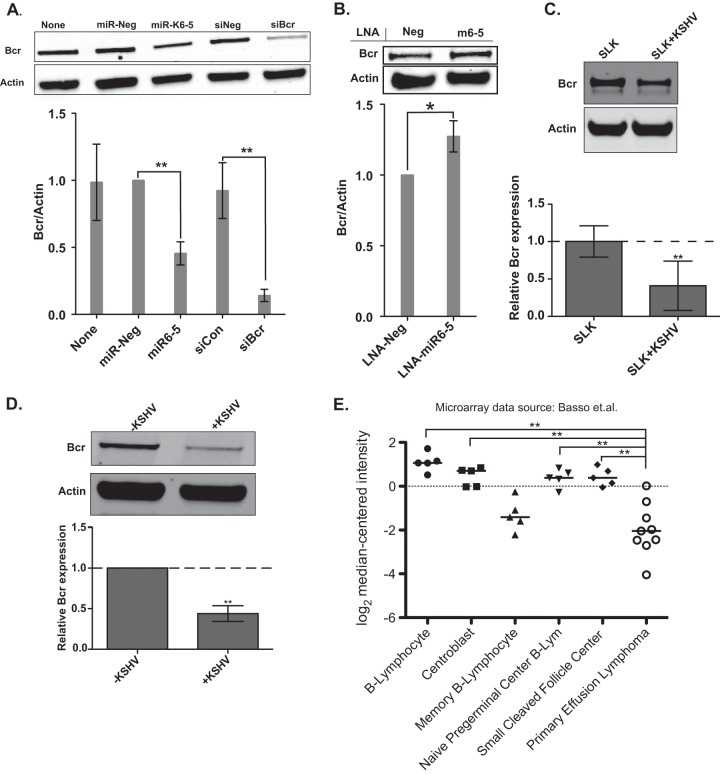

To further validate Bcr as a direct target of KSHV miR-K6-5, we confirmed Bcr knockdown using an siRNA targeting Bcr and found that both miR-K6-5 and siBcr resulted in a robust knockdown of the Bcr protein (P < 0.001), compared to negative controls (Fig. 2A). We also antagonized miR-K6-5 using power-locked nucleic acid inhibitors (power-LNAs) in latently KSHV-infected BCBL-1 cells. We electroporated power-LNAs inhibiting miR-K6-5 (LNA-miR-K6-5) or control LNAs (LNA-Neg) into BCBL-1 cells and measured Bcr/actin protein levels at 48 h postelectroporation. Assuming incomplete miRNA inhibition, we observed that power-LNAs against miR-K6-5 resulted in a statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in the Bcr protein level, compared to LNA-Neg (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Bcr is downregulated by miR-K6-5 and during KSHV infection of endothelial cells. (A) HUVECs were transfected with miR-Neg (control), miR-K6-5, siNeg (siRNA negative control), or siBcr, and the relative levels of Bcr over actin were measured at 48 hpt. The values are averages of data from four independent experiments with P values of <0.001. (B) BCBL-1 cells were electroporated with power-LNAs that inhibit miR-K6-5 along with a negative-control LNA (LNA-Neg). The relative Bcr levels over actin were measured by Western blotting at 48 h postelectroporation. (C) Bcr/actin protein levels were measured in SLK cells (KSHV negative) or in latently KSHV-infected SLK+K cells by Western blotting (top) and plotted (bottom). (D) HUVECs were either mock infected or infected with KSHV, and their Bcr/actin levels were measured by Western blotting (top) and plotted (bottom). (E) Microarray data from NCBI GEO accession number GSE2350 (44), comparing Bcr mRNA expression levels in normal B cell types and KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cells. Horizontal bars indicate median values. Expression values were tested by using a Mann-Whitney U test, and ** indicates a P value of <0.01.

To confirm that Bcr was also downregulated by KSHV in the context of viral infection, we measured Bcr levels in SLK (35, 36) and latently KSHV-infected (SLK+K) (43) cell lines. Bcr protein levels were repressed ∼60% in infected SLK+K cells compared to uninfected SLK cells (Fig. 2C). We also performed de novo KSHV infections of HUVECs and observed that in the context of KSHV infection, there was a 2-fold repression of the levels of Bcr protein (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, we analyzed the reported levels of Bcr mRNA in B cells and B-cell lines using public microarray databases (44) and observed that PEL cells (KSHV positive [KSHV+]) have lower Bcr mRNA levels than do other KSHV-negative B cells. By using a Mann-Whitney test, the Bcr mRNA expression level differences between PEL cells and all B cells (except memory B lymphocytes) were significant (Fig. 2E).

Bcr is derepressed during infection with a KSHV mutant that lacks miR-K6.

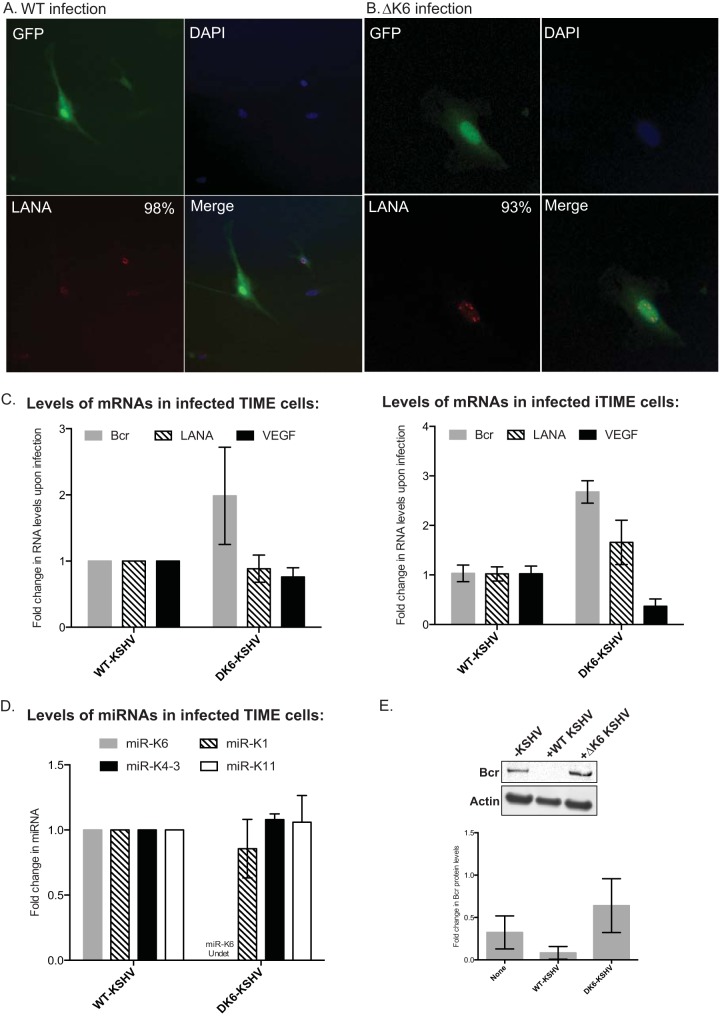

Finally, to confirm that miR-K6-5 was important for Bcr repression in KSHV infection, we infected TIME cells with either wild-type KSHV (WT-KSHV) or a KSHV mutant that lacks miR-K12-6 (ΔK6-KSHV). Infected TIME cells were selected with hygromycin B and allowed to expand to generate a pool of TIME cells that were infected with either WT- or ΔK6-KSHV. Using immunofluorescence, we confirmed that the hygromycin-resistant cells were positive for both green fluorescent protein (GFP) and KSHV LANA (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG 3.

Bcr is derepressed upon infection with a KSHV mutant that lacks miR-K12-6 expression. (A and B) TIME cells were infected with either WT-KSHV (A) or ΔK6-KSHV (B), and infected cells were selected for hygromycin resistance for several weeks. (Left) An immunofluorescence assay was performed to confirm KSHV infection using GFP (top) or LANA (red dots) (bottom) expression. (Right) Infected cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (top), and the merged channels are shown (bottom). The inset numbers state the percentages of infected cells that were positive for LANA expression. (C) Total RNA was extracted from infected TIME cells (left) or iTIME cells (right), and levels of Bcr, VEGF, and LANA were measured by using quantitative RT-PCR. (D) Total RNA was extracted from the infected TIME cells, and levels of KSHV miRNAs miR-K1, -K4-3, -K6-5, and -K11 were measured by using quantitative RT-PCR. (E) TIME cells were left uninfected (lane 1) or infected with either WT-KSHV (lane 2) or ΔK6-KSHV (lane 3), and the levels of Bcr protein were analyzed by Western blotting.

We measured mRNA levels of Bcr, LANA, and VEGF in TIME cells infected with either WT- or ΔK6-KSHV and found that Bcr was derepressed in TIME cells infected with ΔK6-KSHV compared to WT-KSHV (Fig. 3C, left). VEGF mRNA was repressed in ΔK6-KSHV infection compared to WT infection, suggesting a role for miR-K6-5 in both Bcr repression and VEGF activation (Fig. 3C). LANA mRNA levels were comparable between WT- and ΔK6-KSHV infections. Similar results were also obtained with a second endothelial cell line, iTIME, after infection with WT- or ΔK6-KSHV (Fig. 3C, right). We also ensured that the expression of miR-K6 was abrogated in ΔK6-KSHV using real-time PCR (RT-PCR) analysis (Fig. 3D). The levels of the other miRNAs measured, miR-K1, -K4-3, and -K11, were comparable between WT- and ΔK6-KSHV. Western blot analysis showed that while WT-KSHV-infected cells robustly repressed the Bcr protein, infection with ΔK6-KSHV resulted in a near-complete derepression of Bcr levels (Fig. 3E). These results show that miR-K6-5 plays an essential role in the Bcr repression observed during KSHV infections. Together, these results demonstrate that KSHV represses the Bcr protein by using miR-K6-5 during KSHV infection of endothelial cells and B cells.

KSHV miR-K6-5 represses two Rac-GTPase-activating proteins, Bcr and RacGAP1.

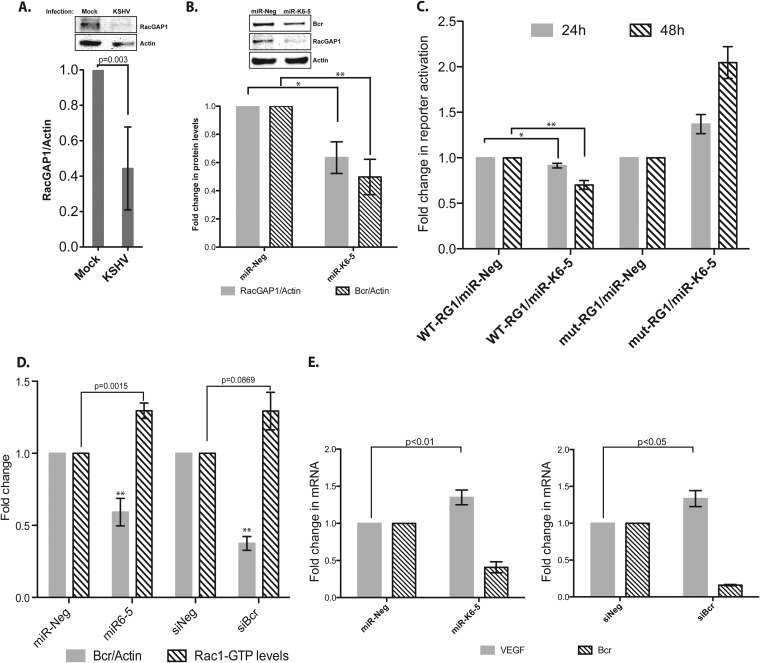

Bcr, being a Rac-GTPase activation protein (GAP), was shown to enhance the intrinsic GTPase activity of Rac1 (28). An analysis of our previously reported microarray data (11) to identify other GAP proteins that might also be repressed by KSHV revealed Rac-GTPase-activating protein 1 (RacGAP1) mRNA as an mRNA that was strongly repressed upon KSHV infection of endothelial cells. Like Bcr, RacGAP1 also negatively regulates Rac-GTPase function by enhancing the hydrolysis of Rac1-bound GTP to GDP (45). RacGAP1 protein levels were repressed ∼60% in KSHV-infected HUVECs compared to mock infections (Fig. 4A). To identify the specific KSHV miRNA that represses RacGAP1, we also measured RacGAP1 protein levels in HUVECs that were transfected with individual KSHV miRNAs. Interestingly, transfection of miR-K6-5 resulted in an ∼40% repression of RacGAP1 protein levels compared to a negative-control miRNA (n = 4; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B, gray bars). As shown in Fig. 2A, miR-K6-5 also repressed Bcr protein levels in transfected HUVECs (n = 4; P < 0.01) (Fig. 4B, hatched bars).

FIG 4.

miR-K6-5 represses Bcr and RacGAP1 and increases Rac1-GTP levels in endothelial cells. (A) HUVECs were either mock infected or infected with KSHV, and their RacGAP1/actin levels were measured by Western blotting (top) and plotted (bottom). (B) HUVECs were transfected with miR-Neg (control) or miR-K6-5, and the relative levels of RacGAP1 over actin were measured at 48 hpt. The level of Bcr protein was used as an additional control. (C) 293 cells were reverse transfected with reporter plasmids wherein a portion of the 3′ UTR of RacGAP1 (WT-RG1) or a mutated version (mut-RG1) was cloned downstream of the Renilla luciferase along with miR-Neg or miR-K6-5. Cells were harvested at 24 or 48 hpt for reporter activity measurements. (D) HUVECs were transfected with miR-Neg, miR-K6-5, siNeg, or siBcr, and their Rac1-GTP levels were measured by using a G-LISA. (E) HUVECs were transfected with either miR-K6-5 or siBcr, along with their corresponding negative controls. VEGF mRNA levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. * denotes a P value of <0.05, and ** denotes a P value of <0.01.

To confirm that RacGAP1 was repressed by miR-K6-5 via a direct interaction, we scanned the 3′ UTR of RacGAP1 using TargetScan and identified an 8-mer binding site for miR-K6-5. We cloned this portion of the 3′ UTR of RacGAP1 downstream of the renilla luciferase reporter (pDEST-765-RG1) and performed 3′-UTR reporter assays. At 48 hpt, we observed that miR-K6-5 suppressed luciferase reporter activity by ∼30%, compared to the miR-Neg control (Fig. 4C). To further confirm direct binding, we also mutated the predicted miR-K6-5 binding site. Mutation of the binding site completely negated the miR-K6-5-mediated repression of the reporter (Fig. 4C), suggesting that miR-K6-5 repressed RacGAP1 mRNA via a direct interaction with the 3′ UTR. The repression of Bcr and RacGAP1, two proteins that negatively regulate Rac1, by the same KSHV miRNA suggests the importance of activation of this pathway in KSHV infections. As Bcr has been described to be a tumor suppressor (22), we focused on understanding the importance of Bcr repression during KSHV infection.

miR-K6-5-mediated repression of Bcr enhances Rac1 activity in endothelial cells.

Active Rac1 plays critical roles in regulating VEGF-induced endothelial cell motility, lumen formation, and, hence, angiogenesis (31, 46, 47). Transgenic mice expressing constitutively active Rac1 developed KS-like tumors (33). As Bcr accelerates the conversion of Rac1-GTP to Rac1-GDP and acts as a negative regulator of Rac1 (28, 48), we hypothesized that the knockdown of Bcr by miR-K6-5 might increase the levels of active Rac1-GTP in HUVECs. We measured the levels of “active” Rac1 in miR-K6-5-transfected HUVECs by measuring the amount of Rac1-GTP bound to a downstream protein using a G-LISA assay. We observed that miR-K6-5-transfected HUVECs had a ∼30% increase in Rac1-GTP levels, compared to the miR-Neg control (Fig. 4D, hatched bars). A Western blot analysis of these transfected HUVECs also showed ∼2-fold repression in the levels of the Bcr protein with miR-K6-5 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4D, gray bars). As additional controls, we also transfected HUVECs with siRNAs targeting Bcr and observed a similar increase in the Rac1-GTP level (∼30%), compared with the siNeg control (Fig. 4D). Together, these results suggest that the knockdown of Bcr by either KSHV miR-K6-5 or siBcr increases the Rac1-GTP levels in HUVECs.

miR-K6-5-transfected HUVECs have increased VEGF levels.

Enhanced Rac1 levels have been linked to increases in angiogenesis. Since VEGF is one of the key factors that promote the process, we measured the levels of VEGF mRNA in miR-K6-5-transfected HUVECs using quantitative PCR. HUVECs were transfected with either miR-K6-5 or miR-Neg, and total RNA was extracted at 48 hpt for measurement of VEGF mRNA levels. We found that miR-K6-5-transfected HUVECs had an ∼35% increase in VEGF mRNA levels, compared to miR-Neg controls (n = 5; P < 0.01) (Fig. 4E). A similar increase in VEGF levels was also observed with an siRNA that targets Bcr (Fig. 4E, right). Thus, knockdown of Bcr with either miR-K6-5 or siRNA can increase both Rac1-GTP levels and VEGF levels in endothelial cells, and this might contribute to the angiogenic phenotype of KS.

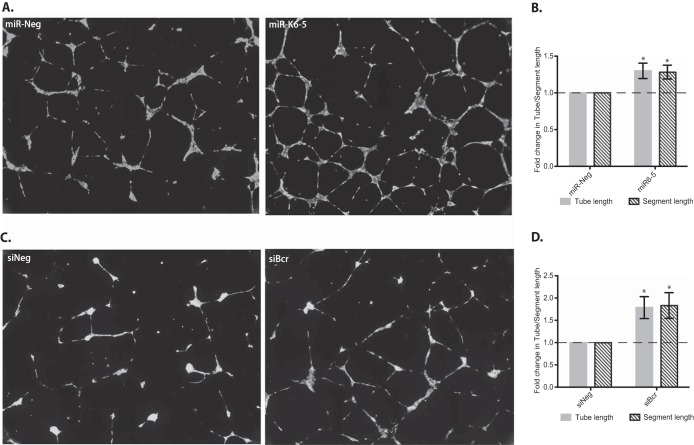

miR-K6-5 and Bcr repression increase tube formation in endothelial cells.

We hypothesized that the increased Rac1 activation (Fig. 4D) and the increased VEGF levels (Fig. 4E) observed for miR-K6-5-transfected HUVECs might lead to increased angiogenesis of endothelial cells (31). To test this hypothesis, we transfected HUVECs with either miR-K6-5 or siBcr and quantified angiogenesis using a basement membrane matrix-based tube formation assay. Briefly, the transfected HUVECs were layered over a basement membrane matrix overnight to allow tube formation (Fig. 5A and C). Using the “angiogenesis tube formation” algorithm in Metamorph, we measured the tube and segment lengths across the entire well area to obtain a complete and unbiased measure of angiogenesis. A sample of the transfected cells was also used for Western blotting to confirm Bcr knockdown for each assay. In tube formation assays, we observed that HUVECs transfected with miR-K6-5 had ∼30% increases in both tube and segment lengths compared to the miR-Neg control (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A and B). Western blot analysis confirmed Bcr repression by miR-K6-5 (Fig. 4D, gray bars). Furthermore, siRNAs targeting Bcr showed ∼80% increases in tube (and segment) length compared to the siNeg control (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5C and D). The greater effect of siBcr on angiogenesis than that of miR-K6-5 is likely due to the fact that the siRNA to Bcr results in a greater degree of knockdown of Bcr protein (∼75%) than does miR-K6-5 (∼50%) (Fig. 2A and 4D). These data show that miR-K6-5 or siRNA-mediated knockdown of Bcr enhances Rac1 activity, endothelial tube formation, and angiogenesis.

FIG 5.

miR-K6-5- or siRNA-mediated repression of Bcr increases tube formation in endothelial cells. (A and C) HUVECs were transfected with miR-Neg or miR-K6-5 (A) and siNeg or siBcr (C) and transferred onto Geltrex at 48 hpt to allow tube formation. The tubes were stained with Calcein AM and imaged as described in Materials and Methods. (B and D) The total lengths of tubes and segments across the complete well area were measured by using Metamorph (Molecular Devices, Inc.) and plotted. The term “segment” defines the extent of branching of a given tube; in other words, a tube is made of many segments. The results are averages of data from three independent experiments, and P values of <0.05 were considered to be significant.

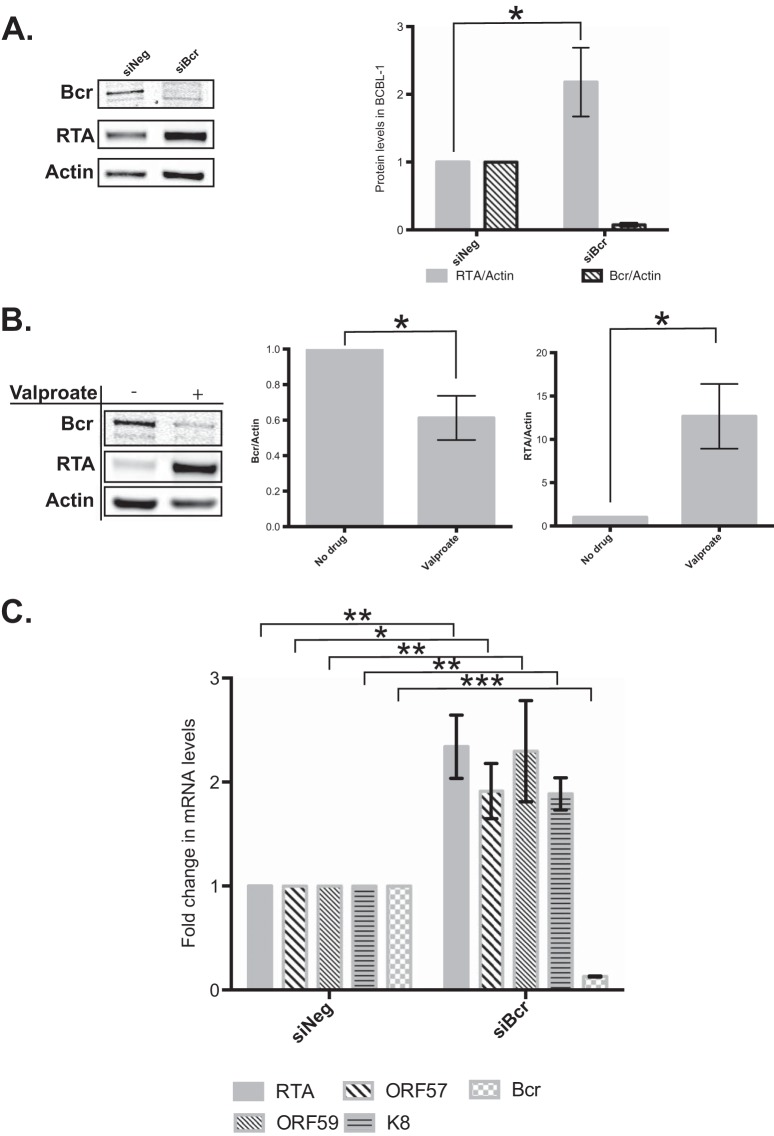

Repression of Bcr stimulates lytic gene expression.

To determine the role of Bcr in KSHV infection, we knocked down Bcr protein expression in BCBL-1 cells (latently infected with KSHV) using siRNAs. We electroporated siRNAs against Bcr into BCBL-1 cells and observed a >95% knockdown in Bcr protein levels at 48 h postelectroporation, compared to the siNeg control (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, knockdown of Bcr via siRNAs resulted in ∼2-fold increases in the levels of the KSHV replication and transcription activator protein (RTA or ORF50). RTA is a transcriptional activator and is the master regulator of KSHV lytic reactivation (49, 50). Bcr repression by KSHV might therefore facilitate the transition from latent infection to lytic reactivation. To understand this further, we also measured the levels of Bcr protein in BCBL-1 cells that were undergoing lytic reactivation upon valproate treatment. As expected, treatment with valproate resulted in ∼10-fold activation of RTA in these cells (Fig. 6B), while Bcr protein was repressed by ∼40%, which may be a result of host shutoff (51).

FIG 6.

Repression of Bcr stimulates lytic gene expression. (A) BCBL-1 cells were electroporated with either control siRNAs (siNeg) or siBcr. Bcr and RTA levels were measured at 48 h postelectroporation, normalized to actin levels, and quantified. (B) BCBL-1 cells were either left untreated or treated with valproate to induce lytic reactivation. Cells were harvested at 24 h posttreatment, and their Bcr and RTA levels were measured and normalized to that of actin. (C) BCBL-1 cells were electroporated with either control siRNAs (siNeg) or siBcr, and mRNA levels of the RTA, ORF57, ORF59, and K8 viral genes were measured by using quantitative RT-PCR.

Finally, we measured the mRNA levels of several KSHV lytic genes in the presence of an siRNA against Bcr. Consistent with the protein data, we observed an ∼2-fold increase in the level of viral RTA mRNA upon Bcr knockdown, relative to siNeg (Fig. 6C). In addition, we also observed similar increases in the levels of the three lytic mRNAs ORF57, ORF59, and K8 upon Bcr knockdown. Together, our data suggest that Bcr repression by KSHV might be beneficial for KSHV to transition from latency into lytic replication.

DISCUSSION

Using an unbiased, microarray-based gene profiling approach, we have identified the breakpoint cluster region (Bcr) mRNA as the cellular target of a KSHV microRNA, miR-K6-5, and demonstrated that the virus utilizes miRNAs to enhance Rac1-GTP levels and promote angiogenesis of endothelial cells. The Bcr protein serves as a negative regulator of Rac1 (28), and its overexpression results in the formation of stress fibers due to its effect on small GTPases, suggesting a potential role for Bcr in cell motility (52). The robust Bcr repression that we observed in miR-K6-5-transfected cells (Fig. 1 and 2) suggested that KSHV might be repressing Bcr to enhance Rac1 activity and promote angiogenesis. Consistent with this hypothesis, Rac1-GTP levels were enhanced in both miR-K6-5- and siBcr-transfected HUVECs (Fig. 4D), and this increase also corresponded to a comparable increase in tube formation in endothelial cells (Fig. 5). We also observed an increase in the level of VEGF mRNA in HUVECs transfected with miR-K6-5 (Fig. 4E). Thus, we describe an important role of viral microRNAs in the establishment of KS-associated angiogenesis and demonstrate a new angiogenic function of Bcr.

The enhancement of Rac1-GTP levels as a consequence of Bcr knockdown might also have implications for other cellular pathways. For instance, active Rac1 can positively regulate NF-κB-dependent transcription and promote the survival of cancer cells (53). By inhibiting Rac1-GTP formation, Bcr also inhibits the activation of p21-activated protein kinase (PAK1) (54). Thus, miR-K6-5-mediated repression of Bcr might also contribute to the increased PAK1 activity that is observed in KSHV-infected HUVECs (32). Furthermore, Rac1 also regulates NAPDH-oxidase and enhances reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. ROS is an important second-messenger molecule and plays numerous roles in the progression of cancer, including the establishment of angiogenesis (for a review, see reference 55). In studies with knockout mice, neutrophils from bcr−/− mice had increased membrane-associated Rac1-GTP levels and ∼2-fold-higher levels of ROS than did wild-type mice (48). However, we were unable to detect an effect of miR-K6-5- or siRNA-mediated Bcr repression on ROS levels (data not shown). One possible reason for this result is the difference in cell types used: the previous study (48) used phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)-activated neutrophils that are specialized in ROS generation, whereas we studied endothelial cells that generate ∼100-fold-lower levels of ROS (56).

While latency is the default pathway in infection by many herpesviruses, the virus should also be able to transition into lytic replication under appropriate conditions. The viral protein RTA regulates this process, and induction of RTA expression activates lytic reactivation in KSHV-infected cells. Repression of cellular factors to regulate the latency-lytic cycle was described previously (11, 18, 57–59). KSHV RTA is itself repressed by miR-K12-9-5, -7-5, and -5 (12, 13, 60). In BCBL-1 cells (latently infected with KSHV), we observed ∼2-fold activation of RTA (and other lytic mRNAs) upon siRNA-mediated Bcr repression. Bcr was also repressed during valproate-mediated lytic reactivation of BCBL-1 cells (Fig. 6). Thus, we describe an important function for miRNA-mediated suppression of Bcr during lytic reactivation of KSHV infection.

KSHV miRNAs have been demonstrated to have numerous roles in the establishment of KS. While the complete repertoire of the cellular targets of these miRNAs is still emerging, we show that KSHV miRNAs repress Bcr, a tumor suppressor (22), and enhance tube formation in endothelial cells. Expression of constitutively active Rac1 stimulated KS-like tumors in animal models, and Rac1 is overexpressed in spindle cells from AIDS-KS biopsy specimens (33). Furthermore, Guilluy et al. demonstrated that KSHV infection increases Rac1-GTP levels in both infected HUVECs and tumor tissue (32). Here, we demonstrate that miR-K6-5-mediated repression of Bcr brings about a similar enhancement in Rac1 activity in HUVECs. Infection of endothelial cells by KSHV is known to enhance angiogenesis by inducing many angiogenic molecules, such as VEGF and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). KSHV proteins such as K1 (61) and viral G protein-coupled receptor (vGPCR) (62) contribute to this process. It is likely that the increased angiogenesis observed with miR-K6-5 is further enhanced in the context of KSHV infection due to the contribution of other viral proteins and/or miRNAs. The combination of these factors may also promote increased proliferation of endothelial cells to promote infection of more cells by KSHV. Complete characterization of the roles played by the KSHV microRNAs and the host factors that they suppress might further our understanding of the establishment of Kaposi's sarcoma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Yarchoan for critical reviews of the manuscript and members of the Ziegelbauer laboratory for their help and support. We thank Michael Kruhlak and the Analytical Imaging Facility at NCI for their assistance with confocal microscopy. We thank Craig McCormick for the iTIME cell line. We are also thankful for the gift of the iSLK wild-type and mutant producer cell lines from Rolf Renne.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med 332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, Moore PS. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 266:1865–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai X, Lu S, Zhang Z, Gonzalez CM, Damania B, Cullen BR. 2005. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:5570–5575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408192102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundhoff A, Sullivan CS, Ganem D. 2006. A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA 12:733–750. doi: 10.1261/rna.2326106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfeffer S, Sewer A, Lagos-Quintana M, Sheridan R, Sander C, Grasser FA, van Dyk LF, Ho CK, Shuman S, Chien M, Russo JJ, Ju J, Randall G, Lindenbach BD, Rice CM, Simon V, Ho DD, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. 2005. Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat Methods 2:269–276. doi: 10.1038/nmeth746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samols MA, Hu J, Skalsky RL, Renne R. 2005. Cloning and identification of a microRNA cluster within the latency-associated region of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 79:9301–9305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9301-9305.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. 2010. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem 79:351–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nachmani D, Stern-Ginossar N, Sarid R, Mandelboim O. 2009. Diverse herpesvirus microRNAs target the stress-induced immune ligand MICB to escape recognition by natural killer cells. Cell Host Microbe 5:376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abend JR, Uldrick T, Ziegelbauer JM. 2010. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis receptor protein (TWEAKR) expression by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNA prevents TWEAK-induced apoptosis and inflammatory cytokine expression. J Virol 84:12139–12151. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00884-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suffert G, Malterer G, Hausser J, Viiliainen J, Fender A, Contrant M, Ivacevic T, Benes V, Gros F, Voinnet O, Zavolan M, Ojala PM, Haas JG, Pfeffer S. 2011. Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus microRNAs target caspase 3 and regulate apoptosis. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002405. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziegelbauer JM, Sullivan CS, Ganem D. 2009. Tandem array-based expression screens identify host mRNA targets of virus-encoded microRNAs. Nat Genet 41:130–134. doi: 10.1038/ng.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellare P, Ganem D. 2009. Regulation of KSHV lytic switch protein expression by a virus-encoded microRNA: an evolutionary adaptation that fine-tunes lytic reactivation. Cell Host Microbe 6:570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin X, Liang D, He Z, Deng Q, Robertson ES, Lan K. 2011. miR-K12-7-5p encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stabilizes the latent state by targeting viral ORF50/RTA. PLoS One 6:e16224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samols MA, Skalsky RL, Maldonado AM, Riva A, Lopez MC, Baker HV, Renne R. 2007. Identification of cellular genes targeted by KSHV-encoded microRNAs. PLoS Pathog 3:e65. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottwein E, Mukherjee N, Sachse C, Frenzel C, Majoros WH, Chi JT, Braich R, Manoharan M, Soutschek J, Ohler U, Cullen BR. 2007. A viral microRNA functions as an orthologue of cellular miR-155. Nature 450:1096–1099. doi: 10.1038/nature05992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skalsky RL, Samols MA, Plaisance KB, Boss IW, Riva A, Lopez MC, Baker HV, Renne R. 2007. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J Virol 81:12836–12845. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01804-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottwein E, Cullen BR. 2010. A human herpesvirus microRNA inhibits p21 expression and attenuates p21-mediated cell cycle arrest. J Virol 84:5229–5237. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00202-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei X, Bai Z, Ye F, Xie J, Kim CG, Huang Y, Gao SJ. 2010. Regulation of NF-kappaB inhibitor IkappaBalpha and viral replication by a KSHV microRNA. Nat Cell Biol 12:193–199. doi: 10.1038/ncb2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Sun R, Lin X, Liang D, Deng Q, Lan K. 2012. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded microRNA miR-K12-11 attenuates transforming growth factor beta signaling through suppression of SMAD5. J Virol 86:1372–1381. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06245-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abend JR, Ramalingam D, Kieffer-Kwon P, Uldrick TS, Yarchoan R, Ziegelbauer JM. 2012. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNAs target IRAK1 and MYD88, two components of the Toll-like receptor/interleukin-1R signaling cascade, to reduce inflammatory-cytokine expression. J Virol 86:11663–11674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01147-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groffen J, Stephenson JR, Heisterkamp N, de Klein A, Bartram CR, Grosveld G. 1984. Philadelphia chromosomal breakpoints are clustered within a limited region, bcr, on chromosome 22. Cell 36:93–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ress A, Moelling K. 2005. Bcr is a negative regulator of the Wnt signalling pathway. EMBO Rep 6:1095–1100. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ress A, Moelling K. 2006. Bcr interferes with beta-catenin-Tcf1 interaction. FEBS Lett 580:1227–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radziwill G, Erdmann RA, Margelisch U, Moelling K. 2003. The Bcr kinase downregulates Ras signaling by phosphorylating AF-6 and binding to its PDZ domain. Mol Cell Biol 23:4663–4672. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.13.4663-4672.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maru Y, Witte ON. 1991. The BCR gene encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase activity within a single exon. Cell 67:459–468. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90521-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ron D, Zannini M, Lewis M, Wickner RB, Hunt LT, Graziani G, Tronick SR, Aaronson SA, Eva A. 1991. A region of proto-dbl essential for its transforming activity shows sequence similarity to a yeast cell cycle gene, CDC24, and the human breakpoint cluster gene, bcr. New Biol 3:372–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitehead IP, Campbell S, Rossman KL, Der CJ. 1997. Dbl family proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1332:F1–F23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diekmann D, Brill S, Garrett MD, Totty N, Hsuan J, Monfries C, Hall C, Lim L, Hall A. 1991. Bcr encodes a GTPase-activating protein for p21rac. Nature 351:400–402. doi: 10.1038/351400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fryer BH, Field J. 2005. Rho, Rac, Pak and angiogenesis: old roles and newly identified responsibilities in endothelial cells. Cancer Lett 229:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ensoli B, Sturzl M. 1998. Kaposi's sarcoma: a result of the interplay among inflammatory cytokines, angiogenic factors and viral agents. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 9:63–83. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(97)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vader P, van der Meel R, Symons MH, Fens MH, Pieters E, Wilschut KJ, Storm G, Jarzabek M, Gallagher WM, Schiffelers RM, Byrne AT. 2011. Examining the role of Rac1 in tumor angiogenesis and growth: a clinically relevant RNAi-mediated approach. Angiogenesis 14:457–466. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guilluy C, Zhang Z, Bhende PM, Sharek L, Wang L, Burridge K, Damania B. 2011. Latent KSHV infection increases the vascular permeability of human endothelial cells. Blood 118:5344–5354. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma Q, Cavallin LE, Yan B, Zhu S, Duran EM, Wang H, Hale LP, Dong C, Cesarman E, Mesri EA, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. 2009. Antitumorigenesis of antioxidants in a transgenic Rac1 model of Kaposi's sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:8683–8688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812688106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahai E, Marshall CJ. 2002. RHO-GTPases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2:133–142. doi: 10.1038/nrc725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herndier BG, Werner A, Arnstein P, Abbey NW, Demartis F, Cohen RL, Shuman MA, Levy JA. 1994. Characterization of a human Kaposi's sarcoma cell line that induces angiogenic tumors in animals. AIDS 8:575–581. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sturzl M, Gaus D, Dirks WG, Ganem D, Jochmann R. 2013. Kaposi's sarcoma-derived cell line SLK is not of endothelial origin, but is a contaminant from a known renal carcinoma cell line. Int J Cancer 132:1954–1958. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vieira J, O'Hearn PM. 2004. Use of the red fluorescent protein as a marker of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic gene expression. Virology 325:225–240. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leidal AM, Cyr DP, Hill RJ, Lee PW, McCormick C. 2012. Subversion of autophagy by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus impairs oncogene-induced senescence. Cell Host Microbe 11:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brulois KF, Chang H, Lee AS, Ensser A, Wong LY, Toth Z, Lee SH, Lee HR, Myoung J, Ganem D, Oh TK, Kim JF, Gao SJ, Jung JU. 2012. Construction and manipulation of a new Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus bacterial artificial chromosome clone. J Virol 86:9708–9720. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01019-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myoung J, Ganem D. 2011. Generation of a doxycycline-inducible KSHV producer cell line of endothelial origin: maintenance of tight latency with efficient reactivation upon induction. J Virol Methods 174:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholz BA, Harth-Hertle ML, Malterer G, Haas J, Ellwart J, Schulz TF, Kempkes B. 2013. Abortive lytic reactivation of KSHV in CBF1/CSL deficient human B cell lines. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003336. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. 2005. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandriani S, Ganem D. 2010. Array-based transcript profiling and limiting-dilution reverse transcription-PCR analysis identify additional latent genes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 84:5565–5573. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02723-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basso K, Saito M, Sumazin P, Margolin AA, Wang K, Lim WK, Kitagawa Y, Schneider C, Alvarez MJ, Califano A, Dalla-Favera R. 2010. Integrated biochemical and computational approach identifies BCL6 direct target genes controlling multiple pathways in normal germinal center B cells. Blood 115:975–984. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang SM, Ooi LL, Hui KM. 2011. Upregulation of Rac GTPase-activating protein 1 is significantly associated with the early recurrence of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 17:6040–6051. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bayless KJ, Davis GE. 2002. The Cdc42 and Rac1 GTPases are required for capillary lumen formation in three-dimensional extracellular matrices. J Cell Sci 115:1123–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soga N, Namba N, McAllister S, Cornelius L, Teitelbaum SL, Dowdy SF, Kawamura J, Hruska KA. 2001. Rho family GTPases regulate VEGF-stimulated endothelial cell motility. Exp Cell Res 269:73–87. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voncken JW, van Schaick H, Kaartinen V, Deemer K, Coates T, Landing B, Pattengale P, Dorseuil O, Bokoch GM, Groffen J, Heisterkamp N. 1995. Increased neutrophil respiratory burst in bcr-null mutants. Cell 80:719–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90350-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lukac DM, Renne R, Kirshner JR, Ganem D. 1998. Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection from latency by expression of the ORF 50 transactivator, a homolog of the EBV R protein. Virology 252:304–312. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun R, Lin SF, Gradoville L, Yuan Y, Zhu F, Miller G. 1998. A viral gene that activates lytic cycle expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:10866–10871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glaunsinger B, Ganem D. 2004. Lytic KSHV infection inhibits host gene expression by accelerating global mRNA turnover. Mol Cell 13:713–723. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng X, Guller S, Beissert T, Puccetti E, Ruthardt M. 2006. BCR and its mutants, the reciprocal t(9;22)-associated ABL/BCR fusion proteins, differentially regulate the cytoskeleton and cell motility. BMC Cancer 6:262. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perona R, Montaner S, Saniger L, Sanchez-Perez I, Bravo R, Lacal JC. 1997. Activation of the nuclear factor-kappaB by Rho, CDC42, and Rac-1 proteins. Genes Dev 11:463–475. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu W, Mayer BJ. 1999. Mechanism of activation of Pak1 kinase by membrane localization. Oncogene 18:797–806. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ushio-Fukai M, Nakamura Y. 2008. Reactive oxygen species and angiogenesis: NADPH oxidase as target for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett 266:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Buul JD, Fernandez-Borja M, Anthony EC, Hordijk PL. 2005. Expression and localization of NOX2 and NOX4 in primary human endothelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal 7:308–317. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He Z, Liu Y, Liang D, Wang Z, Robertson ES, Lan K. 2010. Cellular corepressor TLE2 inhibits replication-and-transcription-activator-mediated transactivation and lytic reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 84:2047–2062. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01984-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kang H, Wiedmer A, Yuan Y, Robertson E, Lieberman PM. 2011. Coordination of KSHV latent and lytic gene control by CTCF-cohesin mediated chromosome conformation. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002140. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Z, Wood C. 2007. The transcriptional repressor K-RBP modulates RTA-mediated transactivation and lytic replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 81:6294–6306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02648-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu F, Stedman W, Yousef M, Renne R, Lieberman PM. 2010. Epigenetic regulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency by virus-encoded microRNAs that target Rta and the cellular Rbl2-DNMT pathway. J Virol 84:2697–2706. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01997-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang L, Wakisaka N, Tomlinson CC, DeWire SM, Krall S, Pagano JS, Damania B. 2004. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) K1 protein induces expression of angiogenic and invasion factors. Cancer Res 64:2774–2781. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bais C, Santomasso B, Coso O, Arvanitakis L, Raaka EG, Gutkind JS, Asch AS, Cesarman E, Gershengorn MC, Mesri EA. 1998. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature 391:86–89. doi: 10.1038/34193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]