ABSTRACT

Inhibitor-of-apoptosis (IAP) proteins are key regulators of the innate antiviral response by virtue of their capacity to respond to signals affecting cell survival. In insects, wherein the host IAP provides a primary restriction to apoptosis, diverse viruses trigger rapid IAP depletion that initiates caspase-mediated apoptosis, thereby limiting virus multiplication. We report here that the N-terminal leader of two insect IAPs, Spodoptera frugiperda SfIAP and Drosophila melanogaster DIAP1, contain distinct instability motifs that regulate IAP turnover and apoptotic consequences. Functioning as a protein degron, the cellular IAP leader dramatically shortened the life span of a long-lived viral IAP (Op-IAP3) when fused to its N terminus. The SfIAP degron contains mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK)-like regulatory sites, responsible for MAPK inhibitor-sensitive phosphorylation of SfIAP. Hyperphosphorylation correlated with increased SfIAP turnover independent of the E3 ubiquitin-ligase activity of the SfIAP RING, which also regulated IAP stability. Together, our findings suggest that the SfIAP phospho-degron responds rapidly to a signal-activated kinase cascade, which regulates SfIAP levels and thus apoptosis. The N-terminal leader of dipteran DIAP1 also conferred virus-induced IAP depletion by a caspase-independent mechanism. DIAP1 instability mapped to previously unrecognized motifs that are not found in lepidopteran IAPs. Thus, the leaders of cellular IAPs from diverse insects carry unique signal-responsive degrons that control IAP turnover. Rapid response pathways that trigger IAP degradation and initiate apoptosis independent of canonical prodeath gene (Reaper-Grim-Hid) expression may provide important innate immune advantages. Furthermore, the elimination of these response motifs within viral IAPs, including those of baculoviruses, explains their unusual stability and their potent antiapoptotic activity.

IMPORTANCE Apoptosis is an effective means by which a host controls virus infection. In insects, inhibitor-of-apoptosis (IAP) proteins act as regulatory sentinels by responding to cellular signals that determine the fate of infected cells. We discovered that lepidopteran (moth and butterfly) IAPs, which are degraded upon baculovirus infection, are controlled by a conserved phosphorylation-sensitive degron within the IAP N-terminal leader. The degron likely responds to virus-induced kinase-specific signals for degradation through SKP1/Cullin/F-box complex-mediated ubiquitination. Such signal-induced destruction of cellular IAPs is distinct from degradation caused by well-known IAP antagonists, which act to expel IAP-bound caspases. The major implication of this study is that insects have multiple signal-responsive mechanisms by which the sentinel IAPs are actively degraded to initiate host apoptosis. Such diversity of pathways likely provides insects with rapid and efficient strategies for pathogen control. Furthermore, the absence of analogous degrons in virus-encoded IAPs explains their relative stability and antiapoptotic potency.

INTRODUCTION

Apoptosis is an effective antiviral response that can determine the outcome of an infection. Host-initiated apoptosis can inhibit virus multiplication and have a profound influence on pathogenicity. In insects, regulation of apoptosis is implemented through the activity of the host's inhibitor-of-apoptosis (IAP) proteins, a family of conserved survival factors that determines cell fate during stress, development, tumorigenesis, and infection (for reviews, see references 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). Because they restrict apoptosis and govern activity of the death proteases known as caspases, the IAPs are subject to multiple levels of control that affect their function and steady-state levels. Current evidence suggests that caspase-mediated apoptosis in invertebrates is primarily decided by a single regulatory IAP (6–11). Thus, the molecular pathways that control intracellular IAP levels constitute a critical facet in the response of insects to pathogens, viruses included.

First discovered as apoptosis suppressors in baculoviruses (12, 13), the IAPs contain highly conserved protein interaction motifs (Fig. 1), including the baculovirus IAP repeats (BIRs). Direct association of caspases with BIRs accounts for the antiapoptotic activity of certain cellular IAPs (2, 5, 14). Disruption of the IAP/caspase complex, either through displacement by IAP antagonists or accelerated IAP turnover, liberates the caspases to execute apoptosis (1, 5, 15–17). Many IAPs possess a C-terminal RING domain (Fig. 1) with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity that is responsible for auto-ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated turnover. As expected for critical regulators of cell fate, the invertebrate IAPs exhibit relatively short half-lives (∼30 min) (14, 15, 17). As a consequence, depletion of intracellular IAP pools causes the rapid onset of apoptosis (6, 8, 18).

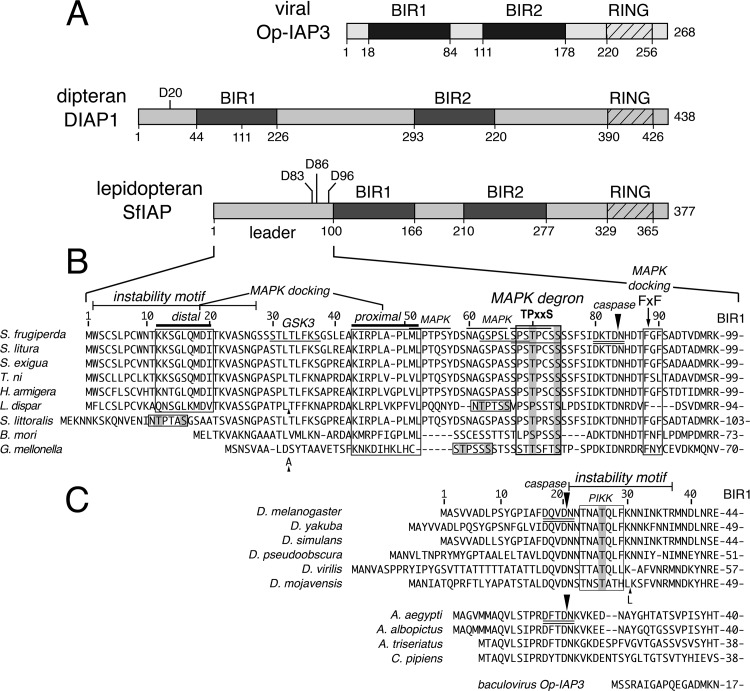

FIG 1.

Insect IAPs. (A) IAP organization. Baculovirus Op-IAP3 (268 residues), Drosophila DIAP1 (438 residues), and Spodoptera SfIAP (377 residues) possess two BIRs (dark boxes) and a single RING domain (crosshatched box); IAP motif boundaries and Asp-containing caspase cleavage sites are marked. (B) Lepidopteran IAP leaders. N-terminal residues are aligned to highlight conserved motifs, including an instability motif (defined herein), an MAPK degron TPxxS motif (x represents any residue), MAPK docking sites (boxed), an FxF MAPK docking motif (boxed), and a caspase cleavage site (closed arrow); potential glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) and MAPK kinase sites (underlined and overlined) are indicated. These regulatory motifs were first recognized by using the Eukaryotic Linear Motif Resource (ELM) as described previously (63) (C) Dipteran and viral IAP leaders. N-terminal leader residues of DIAP1 homologs are aligned relative to their caspase cleavage sites (closed arrow). The DIAP1 instability motif (defined herein) and a conserved phosphoinositide-3-OH-kinase related kinase (PIKK) site are marked. The 17-residue leader of viral Op-IAP3 (bottom) lacks instability and caspase cleavage motifs. IAP accession numbers are listed in Materials and Methods.

Insect IAPs possess domains responsive to signals mediating protein turnover, including those triggered by virus infection. In the case of SfIAP, the principal antiapoptotic IAP of the lepidopteran Spodoptera frugiperda (fall armyworm), the 96-residue N-terminal leader contributes to rapid depletion of SfIAP, and thus apoptosis, after infection with the prototype baculovirus Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) (19, 20). In contrast, baculovirus-encoded Op-IAP3 lacks a comparable leader and is very stable in infected cells (13, 21). Both IAPs are closely related, possessing two BIRs and a C-terminal E3 ligase domain (Fig. 1). Upon deletion of its N-terminal leader, SfIAP is stabilized and inhibits apoptosis in infected cells (19, 20). During infection with AcMNPV, it is virus DNA replication and the resulting engagement of the host cell's DNA damage response (DDR) that triggers SfIAP depletion (19, 22). Thus, it is likely that an instability motif within SfIAP's leader is responsive to DDR signaling, which promotes IAP destruction and apoptosis.

DNA damage is also sufficient to cause depletion of DIAP1, the principal antiapoptotic IAP in Drosophila. Like SfIAP, DIAP1 possesses two BIRs and a C-terminal RING with E3 ligase activity (Fig. 1). DIAP1 depletion releases active caspases, which execute apoptosis (6, 8, 18). Moreover, DIAP1 has many roles in apoptosis, stress, development, and differentiation (reviewed in references 1, 3, 15, and 16). It is not surprising, therefore, that DIAP1 is subject to multiple regulatory schemes at the protein level. After DNA damage, Drosophila DmP53 transcriptionally activates proapoptotic factors, like Reaper, which bind to the BIR and cause DIAP1 degradation by auto-ubiquitination (23, 24). Phosphorylation also regulates DIAP1, as the Drosophila IKK-related kinase DmIKKε promotes proteasome-mediated DIAP1 turnover (25, 26); the phosphorylation sites and mechanisms involved are unknown. In a caspase-mediated cleavage mechanism, the DIAP1 leader also modulates instability through N-end rule ubiquitination pathways (27, 28).

Because of the regulatory role of the N-terminal leader of insect IAPs, we searched for specific motifs therein that affect turnover and thus cell fate. We report here that the lepidopteran SfIAP leader possesses a motif that functions as a classical protein degron by reducing protein stability when present at an N terminus. A well-conserved Ser/Thr-rich domain with sequence similarity to a mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK) degron was necessary for SfIAP phosphorylation, which in turn correlated with IAP instability. Our study suggests that the lepidopteran IAPs use leader-embedded, signal-activated phospho-degrons to regulate the steady-state level of their principal cellular IAP and control virus-induced apoptosis. Similarly, the N-terminal leader of DIAP1 negatively affected its stability. A previously unrecognized motif, absent in the lepidopteran leader, was responsible for DIAP1 turnover. Collectively, these findings suggest that insects employ distinct rapid-response, signal-induced mechanisms for IAP degradation, which can be engaged as an antiviral defense upon infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and infections.

Spodoptera frugiperda IPLB-SF21 cells (29) and Drosophila melanogaster Schneider DL-1 cells (30) were maintained at 27°C in TC100 or Schneider's growth medium (Invitrogen), respectively, supplemented with heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone). For inoculation, extracellular budded virus (BV) of AcMNPV recombinant wt/lacZ (p35+/iap–/polh–, lacZ+) or vΔp35/lacZ (p35–/iap–/polh–, lacZ+) (31) was added to monolayers by using the indicated multiplicity of infection in PFU per cell. For transfections, monolayers were overlaid with medium containing purified plasmid DNA mixed with cationic liposomes consisting of N-[1-(2,3 dioleoyloxy) propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium methyl sulfate-l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine, dioleoyl (C18:1 [cis]-9; DOTAP-DOPE) as described previously (32). AcMNPV late gene expression assays used a lacZ reporter under the control of the polyhedrin promoter of vΔp35/lacZ as described previously (19, 20, 33). Intracellular β-galactosidase was measured 48 h after infection of plasmid-transfected SF21 cells by using a Galacto-Light Plus β-galactosidase chemiluminescent reporter assay (Tropix) and is reported as the average activities ± the standard deviations obtained from triplicate infections. Stably transfected DL-1 cells were selected by hygromycin resistance as described previously (6). The metallothionein (MT) promoter, which directed plasmid expression in pooled cells, was induced by medium containing 500 μg of CuSO4/ml.

Plasmids.

The identity of all plasmids used in the present study was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

(i) sfiap.

The strong, constitutive AcMNPV ie-1 promoter (prm) directs the expression of T7 epitope (MASMTGGQQMG)-tagged SfIAP from plasmids pIE1prm/hr5/sfiapT7/PA, pIE1prm/hr5/sfiap(Δ1-96)T7/PA, pIE1prm/hr5/sfiap(D83A)T7/PA, and pIE1prm/hr5/sfiap(I332A)T7/PA (19). Plasmid pIE1prm/hr5/sfiap(Δ1-96/I332A)T7/PA was generated by using standard PCR-based mutagenesis of pIE1prm/hr5/sfiap(Δ1-96)T7/PA. Plasmids encoding SfIAPT7 deletions were generated by PCR mutagenesis of pIE1prm/hr5/sfiapT7/PA; deleted residues were replaced with Gly-Ser. PCR products containing the appropriate 5′ and 3′ sfiap fragments were fused and replaced the AscI-SpeI fragment of pIE1prm/hr5/sfiapT7/PA to generate plasmids encoding SfIAP with deletions of residues 2 to 16, 2 to 30, 15 to 30, 2 to 52, 2 to 70, 15 to 96, 29 to 96, 51 to 96, 69 to 96, or 84 to 96. PCR mutagenesis of pIE1prm/hr5/sfiapT7/PA was also used to generate pIE1prm/hr5/PA-based vectors (34) that encode T7-tagged SfIAP with the following substitutions: W2F/S3A/C4A, S5A/L6A/P7A, C8A/W9F/N10A, T11A/S14A, K12R/K13R, and C4A/C8A.

(ii) diap1.

Sequences encoding a T7 tag were inserted in place of the hemagglutinin (HA) tag of pMTprm/DIAP1HA (6) to generate pMTprm/diap1T7/PA/IE1prm/hygR/PA (abbreviated pMTprm/DIAP1T7), which was used to produce stable DL-1 cell lines. PCR-based mutagenesis was used to generate pMTprm/DIAP1(D20A)T7 and pMTprm/DIAP1(M1L), which encode D20A- and M1L-mutated DIAP1, respectively. The PstI-HindIII fragment of pBS/DIAP1 (35) and sequences encoding an N-terminal T7 tag were inserted into expression vector pIE1prm/hr5/PA (34) to create pIE1prm/hr5/DIAP1T7. Plasmids encoding N-terminally truncated DIAP1T7 were generated by PCR-amplification of appropriate diap1 fragments, which were also inserted into pIE1prm/hr5/PA to yield plasmids encoding DIAP1(Δ4-20)T7, DIAP1(Δ4-38)T7, DIAP1(Δ20-38)T7, DIAP1(Δ20-30)T7, and DIAP1(Δ31-38)T7; deleted residues were replaced with Gly-Ser.

(iii) Op-IAP3.

The N-terminal HA tag of pIE1prm/hr5/opiapHA/PA (21) was replaced with a T7 tag to generate pIE1prm/hr5/opiapT7/PA. PCR-based mutagenesis was then used to replace sequences encoding the 16-residue leader of Op-IAP3 with those encoding the first 96 residues of SfIAP (Sflead) to generate pIE1prm/hr5/opiap(Sflead)T7/PA. These plasmids were then used to create pIE1prm/hr5/opiap(I223A)T7/PA and pIE1prm/hr5/opiap(Sflead/I223A)T7/PA, which encode I223A-mutated Op-IAP3T7, with or without the SfIAP leader. Sequences encoding an N-terminal T7 tag fused to DIAP1 residues 2 to 37 were PCR amplified from pBS/DIAP1T7 and inserted in place of leader residues 1 to 17 of Op-IAP3. The appropriate fragment encoding Op-IAP3 from the resulting plasmid pBS/Op-IAP(DL) was then inserted into vector pIE1prm/hr5/PA to generate pIE1prm/hr5/Op-IAP(DL)T7/PA.

Small-molecule inhibitors.

Kinase inhibitors SB203580 (Promega), U0126 (Promega), GSK-3 inhibitor IX (Calbiochem), okadaic acid (Sigma), and lactacystin (Calbiochem) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted in TC100 with 10% FBS to the indicated concentrations. Cycloheximide (Sigma) was dissolved in water and diluted in TC100 with 10% FBS to 400 μg/ml. For treatment, cell monolayers (106 cells per 35-mm-diameter plate) were overlaid with drug-containing growth medium for the times indicated.

Immunoblots.

Intact cells and apoptotic bodies were collected by centrifugation, lysed in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 1% β-mercaptoethanol (βME), and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Proteins transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride (Millipore) or nitrocellulose (Osmonics, Inc.) membranes were incubated with the following antisera (diluted as indicated in parentheses): polyclonal anti-SfIAP (1:1,000) affinity-purified as described in reference 20, monoclonal anti-actin (1:5,000; BD Biosciences), monoclonal anti-T7 (1:10,000; Novagen), polyclonal α-IE1 (1:10,000) (36), polyclonal anti-DIAP1 (1:1,000) (6), or polyclonal anti-DrICE (1:1,000) (35). Signal development was conducted by using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) with the CDP-Star chemiluminescent detection system (Roche). Films were scanned at 300 dpi and prepared using CS6 Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

Protein half-life.

Cells transfected 24 h earlier with pIE1prm-based vectors were overlaid with medium containing 400 μg of cycloheximide (CHX) per ml, which was the minimum concentration sufficient to block >95% of SfIAP synthesis over a 4-h period (data not shown). Serial dilutions of cell lysates prepared at the indicated times thereafter were analyzed by PAGE and duplicate immunoblots. Signal intensity was quantified by densitometry (NIH ImageJ) using films exposed within the linear range. The percent protein remaining at each interval after CHX treatment was calculated and plotted as a function of time to generate protein half-lives (t1/2) by using best-fit analysis.

Phosphoprotein analysis.

Cells were collected, freeze-thawed, suspended in phosphatase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1× Complete protease inhibitors [Roche]), and treated with 2 U of calf-intestinal phosphatase as described previously (37). For phosphoprotein staining, proteins were immunoprecipitated by using anti-T7-conjugated agarose beads (Novagen) in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7], 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, 1× protease inhibitor, 1× phosphatase inhibitor [Sigma]). After a washing step with IP buffer, bound protein was eluted by boiling in sample buffer and subjected to PAGE. Gels were stained with the Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein gel stain kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The same gel was subsequently stained for total protein using Sypro Ruby stain (Invitrogen). Signal intensity of protein bands was quantified by densitometry (NIH ImageJ).

Sequence alignments.

CLUSTAL W alignment (38) was performed using MacVector 7.2.3 on the following cellular IAP sequences: Spodoptera frugiperda SfIAP (AAF35285.1), Spodoptera litura IAP (AFA43941), Spodoptera exigua IAP (ABA62322), Spodoptera littoralis IAP (CAM96614), Trichoplusia ni IAP (AAF19819), Helicoverpa armigera IAP (ADM32901), Lymantria dispar (BAM63312), Bombyx mori IAP (AAN46650), Galleria mellonella IAP (ACV04797), Drosophila melanogaster DIAP1 (AAC41609), D. pseudoobscura IAP (EAL30773), D. simulans IAP (GD12518), D. yakuba IAP (GE23121), D. virilis IAP (GJ12099), D. mojavensis IAP (GI13007), Aedes aegypti IAP1 (AAS66751), Aedes albopictus IAP1 (AAL92171), Aedes triseriatus IAP1 (AAL46972), and Culex pipiens IAP (ABP35674).

RESULTS

The N-terminal leader destabilizes SfIAP.

Insect IAPs regulate the fate of uninfected and infected cells (6–8, 10, 11, 19, 39). When cellular IAP levels fall below an antiapoptotic threshold or IAP antagonists disrupt IAP-caspase complexes, caspase-dependent apoptosis ensues. Upon baculovirus infection, Spodoptera SfIAP is rapidly depleted, thereby initiating caspase activation (19, 20). To define the mechanisms of this turnover, we searched for determinants of instability embedded in the 96-residue SfIAP leader (Fig. 1). First, we developed a sensitive assay to compare the stabilities of SfIAPs bearing engineered mutations. To this end, N-terminal T7 epitope-tagged versions of SfIAP were produced in native SF21 cells by plasmid transfection and protein turnover was monitored after treatment with cycloheximide at a concentration sufficient to block >95% of SfIAP synthesis. In this assay, wild-type SfIAPT7 exhibited a half-life of 27 ± 4 min, which was indistinguishable from that of endogenous SfIAP (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, SfIAP(Δ1-96)T7, which lacks the N-terminal leader, was seven times longer-lived (t1/2 = 190 min) under these conditions (Fig. 2A and B). Inactivation of the E3 ligase of the C-terminal RING increased stability of SfIAP(I332A)T7 to a comparable level (Fig. 2A), as expected due to the RING's role in auto-ubiquitination and turnover (17). We concluded that the N-terminal leader destabilizes SfIAP, a finding consistent with observations in baculovirus-infected cells and insect cell extracts (19, 20).

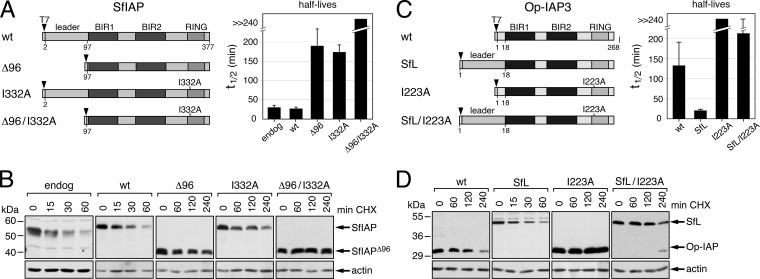

FIG 2.

SfIAP leader-conferred protein instability. (A) SfIAP mutations. The half-lives of wild-type (wt) and mutated SfIAPT7 constructs shown on the left were determined using best-fit analysis of three independent experiments described in panel B. The average values (in minutes) ± the standard deviations of protein half-lives (t1/2) are shown on the right. The RING substitution I332A inactivates SfIAP ubiquitin ligase activity (20). The N-terminal T7 epitope tag did not affect protein stability or function (data not shown). (B) Immunoblots. SF21 cells transfected with plasmids encoding the indicated SfIAPT7 constructs were lysed at various times after cycloheximide (CHX) treatment and subjected to α-T7 immunoblot and densitometric analysis; the results from a representative experiment are shown. Endogenous SfIAP was detected by using anti-SfIAP serum. Actin was used as a loading control throughout the present study. Molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated. (C) Op-IAP3 chimeras. Half-lives ± the standard deviations (right) of wild-type (wt), I223A-mutated, and chimeric Op-IAP3T7 constructs were determined as described in panel A. For the chimeras, SfIAP leader (SfL) residues 1 to 96 replaced Op-IAP3 residues 6 to 16. (D) Immunoblots. SF21 cells transfected with plasmids encoding the indicated Op-IAP3T7 constructs were analyzed as described in panel B.

SfIAP leader-conferred instability is cis-dominant.

Although viral IAPs are closely related to cellular IAPs (Fig. 1), they lack a comparable N-terminal leader (20, 27). We therefore tested the influence of the SfIAP leader on a highly stable viral IAP, Op-IAP3 from alphabaculovirus OpMNPV. We generated chimeric protein Op-IAP3(SfL)T7 in which the short 16-residue leader of Op-IAP3 was substituted with the N-terminal 96 residues (SfL) from SfIAP (Fig. 2C). In stability assays (Fig. 2C and D), the half-life of Op-IAP3(SfL)T7 (t1/2 = 21 ± 4 min) was six times shorter than that of wild-type Op-IAP3T7 (t1/2 = 133 min). Inactivation of the ubiquitin E3 ligase of the Op-IAP3 RING by alanine-substitution of Ile223 (I223A) (20) increased the stability of chimeric Op-IAP3(SfL)T7. However, RING-defective Op-IAP3(SfL)T7 was still less stable than RING-defective Op-IAP3 (Fig. 2C). Thus, the SfIAP leader shortened Op-IAP3's life span even in the absence of RING function, which is consistent with the suggestion that the enhanced stability of viral IAPs is due to loss of a destabilizing leader from an acquired host IAP gene (19, 20, 27).

The SfIAP leader possesses an instability motif.

Caspase-mediated cleavage of the N-terminal leaders of insect IAPs has been implicated in IAP turnover through N-end rule ubiquitination pathways (27, 28). The SfIAP leader contains a caspase consensus site DKTD83↓N (Fig. 1), which is sensitive to cleavage (20). However, when potential caspase cleavage was eliminated by D83A substitution (20, 27), the half-life of SfIAP(D83A)T7 (t1/2 = 35 min) was comparable to that of wild-type SfIAPT7 (Fig. 3A and B). Deletion of leader residues encompassing two other proximal cleavage sites, DNHD86T and DTVD96M (Fig. 1), also had little effect on SfIAP stability (see below). We concluded that under normal, nonapoptotic conditions caspase activity does not influence SfIAP turnover. SfIAP depletion during viral infection is also caspase independent (19, 20).

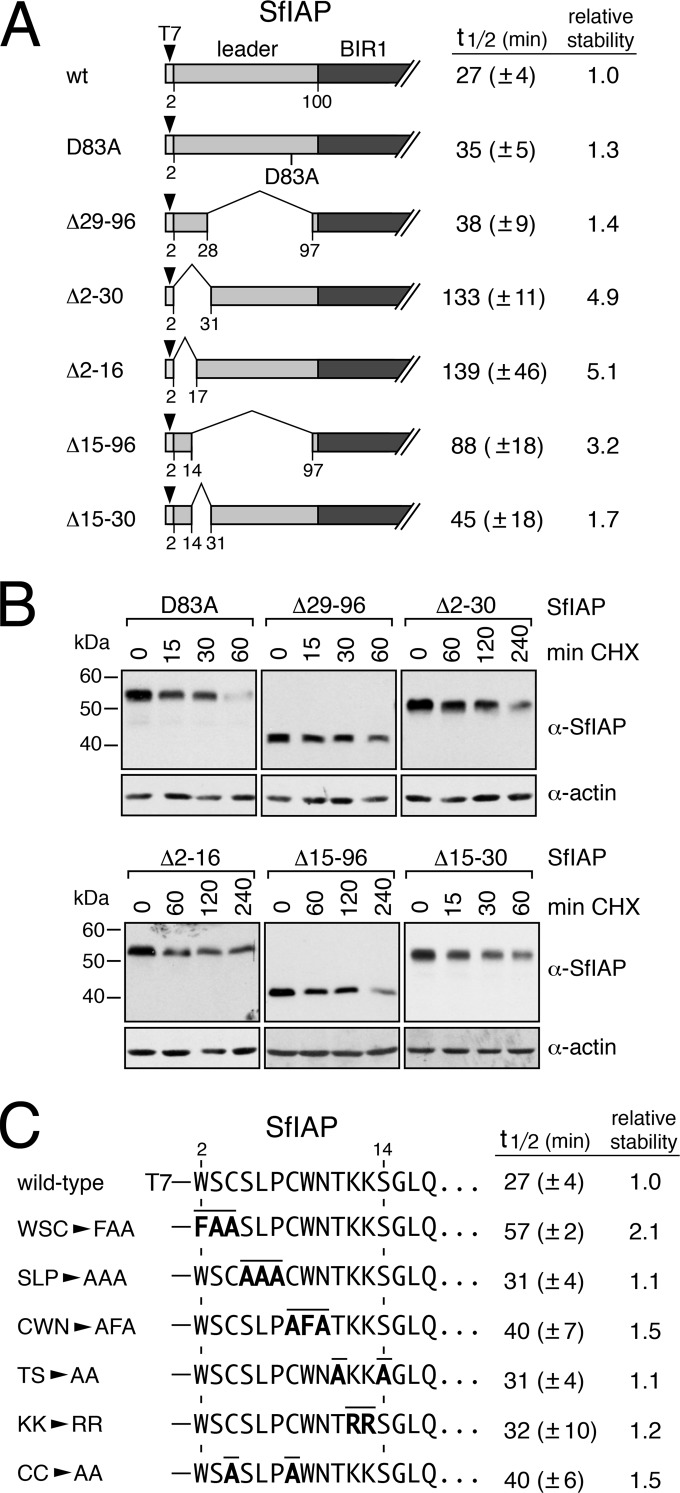

FIG 3.

Identification of SfIAP instability motifs. (A) Protein stability. The average half-lives (in minutes) ± the standard deviations of the indicated SfIAPT7 constructs were determined from three independent experiments in SF21 cells as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The relative stability of each construct was normalized to that of wild-type SfIAPT7 (right). (B) Immunoblots. Half-life measurements for the samples listed in panel A were made using lysates prepared at the indicated times after CHX treatment and subjected to α-T7 immunoblot analysis as described in the legend to Fig. 2; the results from a representative experiment are shown. (C) Leader substitutions. The half-lives (in minutes) ± the standard deviations of SfIAPT7 with the indicated mutations (overlined) were determined as described in panel A; stability relative to that of wild-type SfIAPT7 is shown (right).

To identify the elements within the leader responsible for SfIAP turnover, we used deletion analyses. The largest deletion of residues 15 to 96 within SfIAP(Δ15-96)T7 (t1/2 = 88 min) increased stability 3.2-fold (Fig. 3A). However, the excision of residues 2 to 30 and 2 to 16 of SfIAP(Δ2-30)T7 (t1/2 = 133 min) and SfIAP(Δ2-16)T7 (t1/2 = 139 min), respectively, lengthened SfIAP's life span ∼5-fold. Because deletion of residues 15 to 30 in SfIAP(Δ15-30)T7 had only a modest effect on stability (Fig. 3A), leader residues 2 to 14 had the greatest destabilizing effect. We examined this stretch in greater detail by using substitution mutations (Fig. 3C). Surprisingly, none of the two or three residue substitutions affected stability by more than 2-fold and most had little or no effect (Fig. 3C). For example, substitution of K12 and K13, representing potential sites for ubiquitination, increased SfIAPT7 stability only 1.2-fold. These findings suggested that functional redundancy exists among individual residues comprising a larger instability motif (see below).

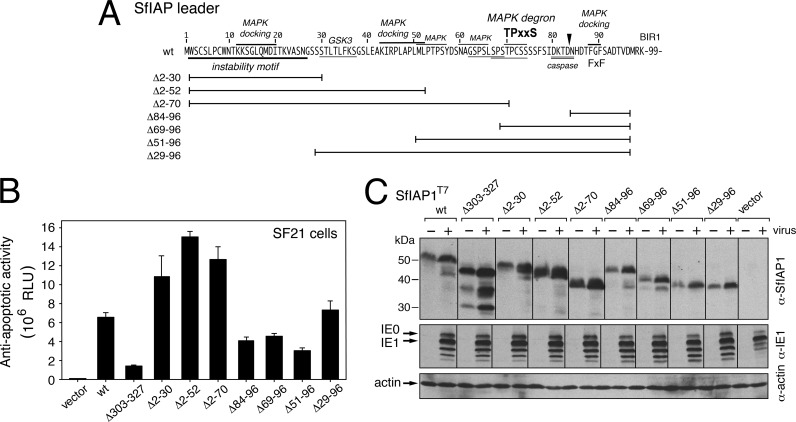

SfIAP instability motifs enhance an antiviral response.

By reacting to host innate signals, the instability motifs of the SfIAP leader could mediate antiviral activities by stimulating host IAP depletion and subsequent apoptosis. We therefore tested the effect of various sections of the leader, including the instability motif, on baculovirus multiplication. To this end, we transfected permissive SF21 cells with plasmids encoding mutated forms of SfIAP and infected them with AcMNPV vΔp35/lacZ (19, 20). Lacking encoded apoptosis inhibitors, this virus possesses a very late polyhedrin promoter-directed lacZ reporter gene. Because this promoter is only active when apoptosis is repressed, the reporter provides a sensitive measure of apoptosis and thus the relative stability of the transfected SfIAP construct (19, 20). Upon transfection, wild-type SfIAPT7 inhibited apoptosis and increased β-galactosidase yields of vΔp35/lacZ by ∼300-fold compared to that of infected cells transfected with vector alone (Fig. 4B). Deletions of the leader residues 2 to 30, 2 to 52, or 2 to 70 (Fig. 4A) increased lacZ expression as much as 2.3-fold compared to wild-type SfIAPT7. This enhanced virus replication coincided with higher steady-state levels of these SfIAP mutations (Fig. 4C). In each case, the SfIAP level in infected cells was boosted comparably due to AcMNPV IE1-mediated transactivation of the expression vector (19, 20). All infections produced comparable levels of IE1, indicating normal viral entry and early gene expression (Fig. 4C). In contrast, SfIAP leader deletions extending from residue 96 toward the N terminus (Δ84-96, Δ69-96, Δ51-96, and Δ29-96) accumulated to lower levels and failed to boost reporter expression as effectively as wild-type SfIAPT7 (Fig. 4B). Deletion of residues 303 to 327, adjacent to the C-terminal RING, which likely inhibits RING activity (data not shown), caused the greatest reduction in proviral function despite high steady-state levels. Collectively, our findings indicated that residues in the N-terminal half of the SfIAP leader confer the greatest level of instability and respond to virus-induced signals that deplete SfIAP.

FIG 4.

Virus-responsive SfIAP instability motifs. (A) SfIAP deletions. The indicated SfIAPT7 leader residues (bars) were replaced with Gly-Ser; identified regulatory motifs are marked. (B) SfIAP complementation of virus replication. SF21 cells transfected 24 h earlier with plasmids encoding wild-type (wt) SfIAPT7 or the indicated deletions were infected with AcMNPV recombinant vΔp35/lacZ and assayed for intracellular β-galactosidase 48 h later. The lacZ reporter of vΔp35/lacZ, controlled by the very late polyhedrin promoter, provides a sensitive measure of virus replication that is only active upon apoptotic suppression and is directly proportional to the stability of plasmid-expressed SfIAPT7. Values shown are the average relative light units (RLU) ± the standard deviations obtained from triplicate infections. (C) Immunoblots. Cells transfected with the SfIAPT7 constructs described in panel B were lysed 24 h after mock infection (−) or infection (+) with vΔp35/lacZ and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-SfIAP (top), anti-IE1 (middle), or anti-actin (bottom).

The SfIAP leader regulates phosphorylation.

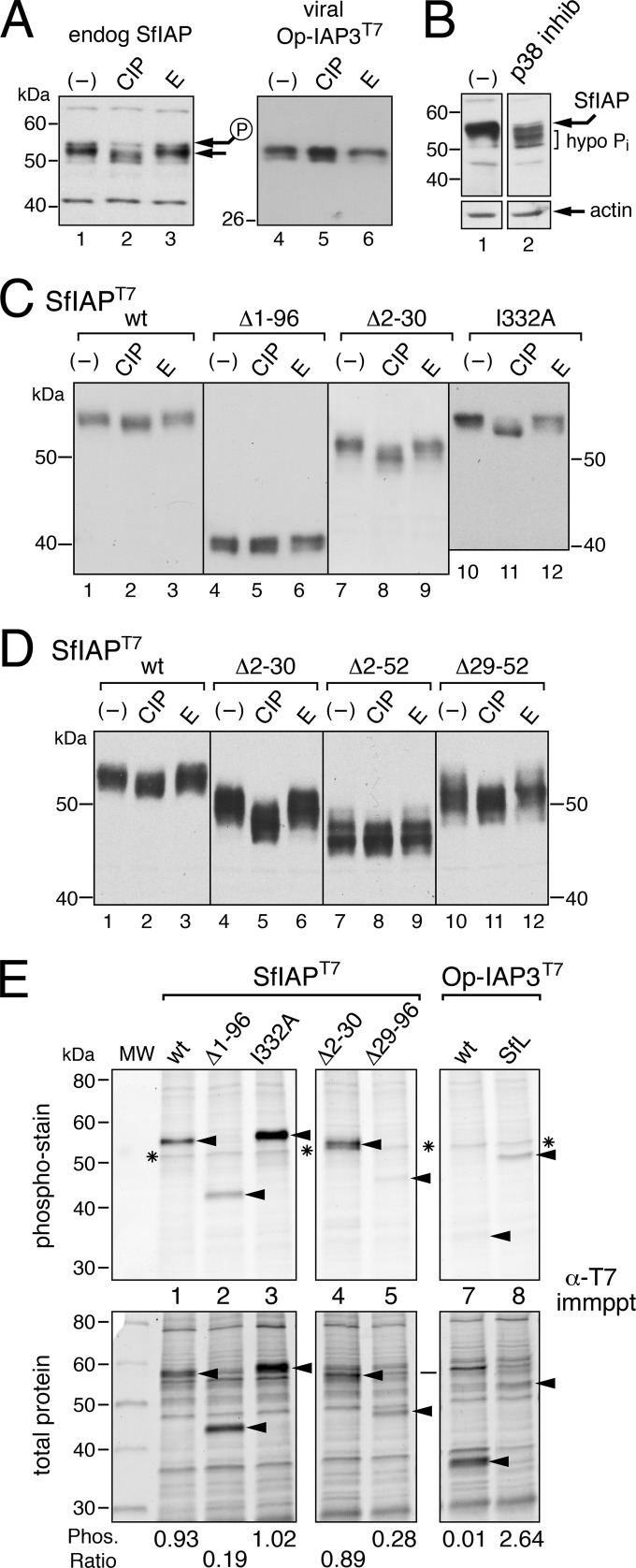

In infected cells, removal of SfIAP residues 2 to 52 conferred the highest level of virus complementation (Fig. 4B). Closer inspection of nine lepidopteran IAP leaders revealed Ser-/Thr-rich stretches and other sequences (see below) that are well conserved (Fig. 1). Because phosphorylation can influence IAP turnover (26, 40, 41), albeit by poorly understood mechanisms, we investigated the leader's role in modulating SfIAP phosphorylation. First, calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) was used to assess the presence of surface-exposed phosphates. When assayed on high-resolution gels, CIP increased the electrophoretic mobility, suggesting a reduced mass, of endogenous SfIAP from cytosolic extracts, whereas the phosphatase inhibitor EDTA did not (Fig. 5A). Overexpressed SfIAPT7 (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 to 3) was also sensitive to CIP, but viral Op-IAP3T7 was not (Fig. 5A, lanes 4 to 6). To confirm this phosphorylation, we used phospho-specific staining of immunoprecipitated proteins by using Pro-Q Diamond quantitative detection (42). Immunoprecipitated SfIAPT7 but not Op-IAP3T7 was readily detected as a phosphoprotein (Fig. 5E, compare lanes 1 and 7).

FIG 5.

SfIAP phosphorylation. (A) Phosphatase treatment. Equal aliquots of soluble extract from normal SF21 cells (endog SfIAP) or those transfected 24 h earlier with plasmid encoding Op-IAP3T7 were not treated (−) or treated with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) or 50 mM EDTA (E), boiled in 1% SDS-1% βME, and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-SfIAP (lanes 1 to 3) or anti-T7 (lanes 4 to 6). The larger, hyperphosphorylated species (P) is marked. Molecular mass standards (in kDa) are indicated. (B) Kinase inhibition. SF21 cells were untreated (−) or treated with 15 μM SB203580 (p38 inhib) for 24 h and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-SfIAP (top) or anti-actin (bottom); hypo Pi denotes the hypophosphorylated forms of endogenous SfIAP. (C and D) Phosphatase-treated SfIAP mutations. Extracts from SF21 cells transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type (wt) or the indicated SfIAPT7 constructs were treated as described in panel A and subjected to anti-T7 immunoblot analysis. (E) Phospho-specific staining. The indicated SfIAPT7 or Op-IAP3T7 constructs (arrows) were immunoprecipitated from plasmid-transfected SF21 cells using anti-T7 beads, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized first with Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein stain (top) and then with Sypro Ruby total protein stain (bottom). An endogenous protein of unknown origin is marked (*). Size standards (in kDa) are indicated (lane MW). Densitometry was used to measure the relative level of phospho-specific stain. These values were then divided by the Sypro stain value for each protein to determine the phosphorylation ratio (bottom).

Next, we identified leader residues required for phosphorylation. Complete removal of the SfIAP leader reduced phosphorylation, as leaderless SfIAP(Δ1-96)T7 was resistant to CIP (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 to 6) and exhibited reduced phospho-specific staining (Fig. 5E, lane 2). To quantitatively compare phosphorylation levels, we calculated the ratio of phospho-specific signal to the level of immunoprecipitated protein for each construct (Fig. 5E, bottom). The phosphorylation ratio of leaderless SfIAP(Δ1-96)T7 was 5-fold lower than that of full-length SfIAPT7. Removal of residues 29 to 96 of SfIAP(Δ29-96)T7, which included the Ser/Thr-rich region, also reduced phosphorylation by 4-fold (Fig. 5E). The finding that SfIAP(Δ2-30)T7 was phosphorylated (Fig. 5D, lanes 4 to 6 and Fig. 5E, lane 4) but SfIAP(Δ2-52)T7 was not (Fig. 5D, lanes 7 to 9) indicated that a phosphorylation motif is located between residues 31 to 52 (see below). Not surprisingly, the RING is not required for phosphorylation as RING-defective SfIAP(I332A)T7 was readily phosphorylated (Fig. 5C and E). Lastly, we demonstrated that SfIAP leader-mediated phosphorylation is cis-dominant. When the SfIAP leader was fused to viral Op-IAP3, phosphorylation of chimeric Op-IAP3(SfL)T7 increased >200-fold (Fig. 5E, compare lanes 7 and 8). We concluded that the SfIAP leader is necessary and sufficient for IAP phosphorylation.

Identification of a phospho-degron.

Inspection of the leader residues required for phosphorylation revealed an MAPK degron consisting of the motif TPCSS (residues 70 to 74). Comparably positioned in most lepidopteran IAP leaders (Fig. 1B), this motif matches the mammalian phospho-degron consensus TPxxS (43, 44). MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of the Thr and Ser of MAPK-degrons (Fig. 1B, underlined) is required for interaction with an F-box component of SKP1/Cullin/F-box (SCF) complexes, which are involved in ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the phosphorylated substrate (43, 44). To enhance specificity of kinase binding (45, 46), the TPxxS acceptor motif is typically preceded by a MAPK docking motif and followed by an FxF motif. The SfIAP leader possesses two consensus docking motifs, KKSGLQMDI (residues 11 to 19) and KIRPLAPLML (residues 43 to 52), and an FxF motif (residues 88 to 90). Importantly, the motifs are highly conserved among lepidopteran IAP leaders (Fig. 1B) but not among dipteran IAP leaders (Fig. 1C).

MAPKs play key roles in the regulation of apoptosis, cell cycle progression, and cellular stress of animals, insects included (reviewed in references 47, 48, 49, and 50). Thus, to test the possible role of MAPK in SfIAP phosphorylation, we tested three kinase inhibitors (SB203580, U0126, and GSK-3 inhibitor IX) that target vertebrate MAPK p38, ERK, and GSK-3β kinases, respectively (51–53). Only the MAPK p38 inhibitor SB203580 reduced SfIAP phosphorylation as indicated by its capacity to increase electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 5B); U0126 and inhibitor IX had no effect (data not shown). This finding suggested that a p38-like Spodoptera MAPK is responsible for SfIAP phosphorylation, either directly or indirectly. Further studies are required to identify which SfIAP residues are phosphorylated.

Hyperphosphorylation correlates with SfIAP instability.

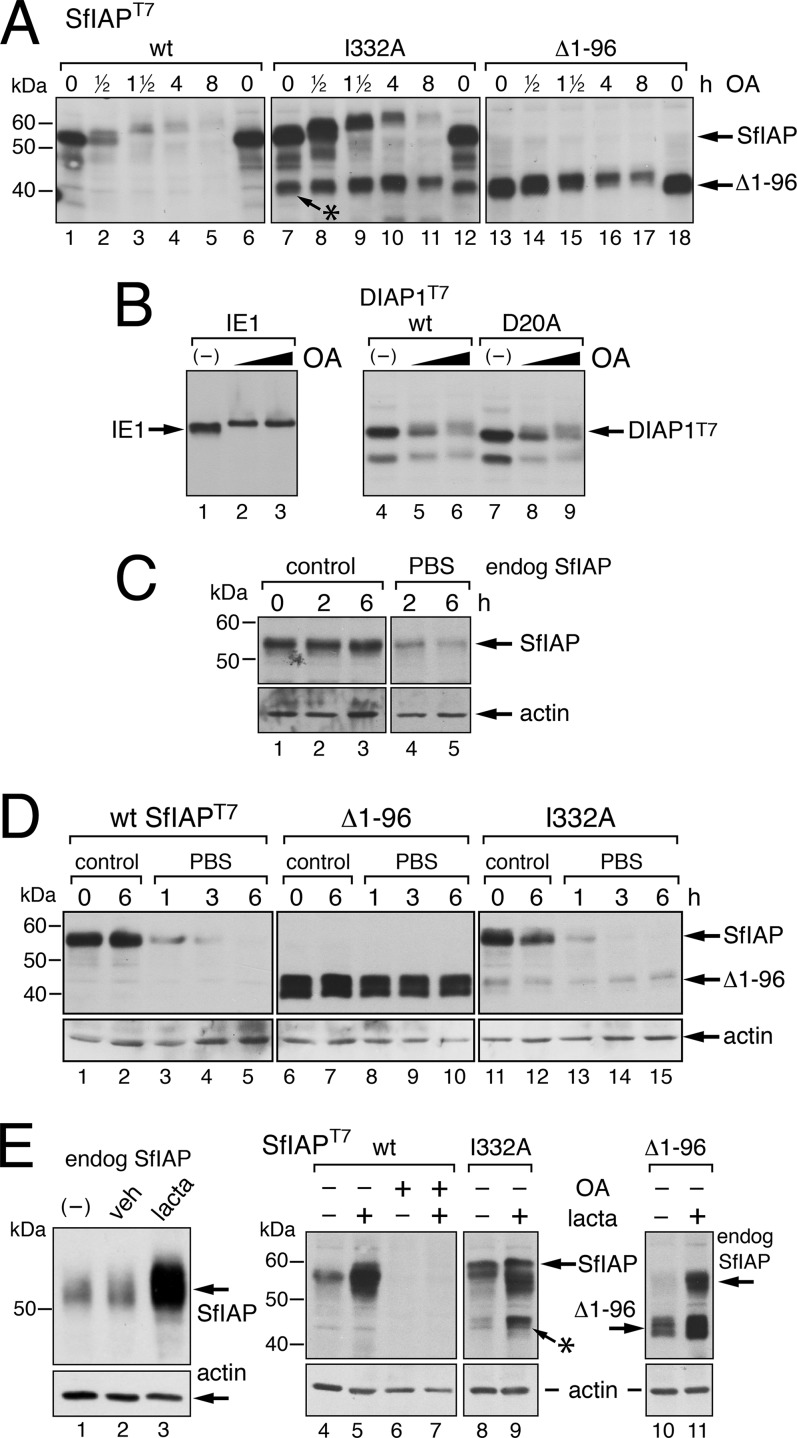

To investigate phosphorylation-mediated SfIAP turnover, we used okadaic acid as a means to stimulate SfIAP phosphorylation. Okadaic acid increases intracellular kinase activities by inhibiting the phosphatases that negatively regulate these kinases (54). Upon okadaic acid treatment, full-length SfIAPT7 increased in mass as indicated by reduced electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 to 5). The sensitivity of okadaic acid-treated SfIAP to CIP treatment confirmed that the increased size was due to phosphorylation (data not shown). Importantly, SfIAPT7 hyperphosphorylation correlated with increased protein turnover; endogenous SfIAP behaved similarly (data not shown). In contrast, leaderless SfIAP(Δ1-96)T7 increased minimally in size and was relatively stable over 8 h of treatment (lanes 13 to 17). Okadaic acid also caused SfIAP(I332A)T7 hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 6A, lanes 7 to 11). The rapid depletion of this RING-defective IAP suggested that the ubiquitin E3 ligase activity of the RING is not required for phosphorylation-induced turnover. Notably, a prominent SfIAP(I332A)T7 fragment (*) was insensitive to okadaic acid-induced turnover (Fig. 6A, lanes 7 to 12, asterisk). This smaller fragment lacks the leader due to caspase cleavage, which results from SfIAP(I332A)T7-mediated dominant inhibition of endogenous SfIAP (20). Despite having nearly identical half-lives (Fig. 2A), phosphorylation-responsive SfIAP(I332A)T7 disappeared over 8 h, whereas the leaderless cleavage fragment and nonphosphorylated SfIAP(Δ1-96)T7 remained relatively constant. We concluded that leader-mediated phosphorylation destabilizes SfIAP.

FIG 6.

Signal-induced turnover of SfIAP. (A) Okadaic acid. SDS lysates of SF21 cells transfected 24 h earlier with plasmids encoding wild-type (wt), I332A-mutated, or leaderless SfIAP(Δ1-96)T7 were prepared at the indicated times (in hours) after treatment with 100 nM okadaic acid (OA) and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-SfIAP; the asterisk denotes the leaderless cleavage fragment of SfIAP(I332A)T7. Anti-actin immunoblots (not shown) demonstrated that total protein levels were unaffected during treatment. (B) Specificity of turnover. Cells transfected 24 h earlier with plasmids encoding AcMNPV phosphoprotein IE1, wild-type (wt), or D20A-mutated DIAP1T7 were treated without (−) or with 50 to 200 nM OA for 2 h and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using IE1- or DIAP1-specific antisera. (C) Stress-induced SfIAP turnover. SF21 cells were overlaid with growth medium (control) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for the indicated times (hours), lysed, and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-SfIAP (top) or anti-actin (bottom). (D) Resistance to stress-induced turnover. SF21 cells transfected 24 h earlier with plasmids encoding wild-type (wt) or the indicated SfIAPT7 constructs were overlaid with medium or PBS and analyzed as described in panel C. (E) Proteasome inhibition. Lysates prepared from SF21 cells either untreated (−) or treated 12 h with DMSO vehicle (veh) or 16 μM lactacystin (lacta) were subjected to immunoblot analysis (lanes 1 to 3) as described in panel C. SF21 cells transfected 20 h earlier with plasmids encoding the indicated SfIAPT7 constructs were treated with (+) or without (−) 16 μM lactacystin (lacta) for 4 h, followed by 100 nM OA for 6 h (+), lysed, and analyzed (lanes 4 to 11); the asterisk indicates cleaved SfIAP(I332A)T7.

To verify that okadaic acid-induced turnover was IAP specific, we tested the stability of baculovirus transactivator IE1, which is also phosphorylated at an N-terminal motif (37). Upon okadaic acid treatment, IE1 was phosphorylated but remained stable (Fig. 6B, lanes 1 to 3). In contrast, okadaic acid increased the mass and instability of wild-type and D20A-mutated Drosophila DIAP1 (lanes 4 to 9), which is also destabilized upon phosphorylation (26).

The SfIAP leader confers stress-induced protein instability.

To determine whether the SfIAP instability motifs are sensitive to signals other than virus infection, we evaluated the effect of stress on IAP turnover. In lepidopteran cells, nutrient deprivation is sufficient to trigger a nonapoptotic stress response (55, 56). Thus, we used serum-free, isotonic buffer (phosphate-buffered saline) for this purpose. Upon incubation, endogenous SfIAP (Fig. 6C) and overexpressed SfIAPT7 (Fig. 6D, lanes 1 to 5) disappeared rapidly. Despite the loss of SfIAP, minimal effector caspase activation (Sf-caspase-1) was detected (R. Vandergaast, N. Byers, and P. Friesen, unpublished data). Remarkably, leaderless SfIAP(Δ1-96)T7 was fully resistant to stress-induced depletion, as steady-state levels were unchanged over the 6-h incubation (Fig. 6D, lanes 6 to 10). RING-defective SfIAP(I332A)T7 (lanes 11 to 15) also disappeared at a rate comparable to that of full-length SfIAPT7. Thus, the SfIAP RING was not required for stress-induced turnover.

SfIAP's leader and RING confer differential regulation.

To confirm the RING independence of SfIAP leader-mediated turnover (Fig. 6), we compared the destabilizing activities of both motifs. The half-life of RING-defective SfIAP(I332A)T7 was 5-fold greater than wild-type SfIAP (Fig. 2A), as expected due to RING-mediated auto-ubiquitination and turnover (17). However, removal of the leader from RING-defective SfIAP further increased stability, since no loss of SfIAP(Δ1-96/I332A)T7 was detected over a 4-h period (Fig. 2B). Thus, the leader contributes to instability even without the E3 ligase activity of the RING. Moreover, the irreversible proteasome inhibitor lactacystin increased the steady-state levels of endogenous SfIAP, overexpressed SfIAPT7, and leaderless SfIAP(Δ1-96)T7 (Fig. 6E, lanes 3, 5, and 11), thus confirming the role of the proteasome in RING-mediated turnover. Lactacystin also increased levels of RING-defective SfIAP(I332A)T7 (Fig. 6E, lane 9), indicating that the proteasome contributes to leader-mediated turnover as well. Interestingly, okadaic acid stimulated turnover of full-length SfIAPT7 even after a 4-h treatment with lactacystin (Fig. 6E, lanes 6 and 7). Not ruled out is the possibility that okadaic acid disrupts the inhibitory effect of lactacystin. We concluded that SfIAP is responsive to degradative pathways that are both dependent and independent of the proteasome.

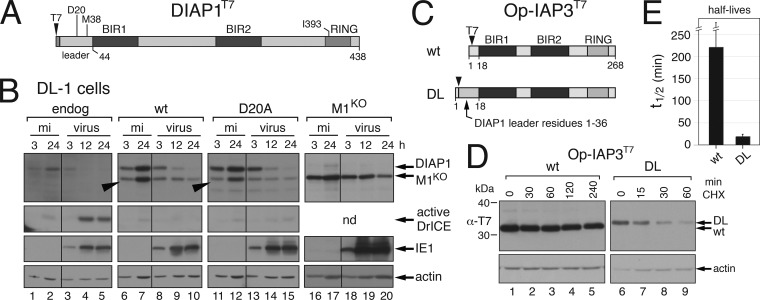

The DIAP1 leader confers protein instability.

DIAP1 is the principal life-or-death IAP of Drosophila. Like lepidopteran IAPs, dipteran DIAP1 has a short 30-min half-life, and its depletion releases a block to apoptosis (1, 3, 16). However, the short N-terminal leader of DIAP1 (Fig. 7A) bears minimal sequence similarity to other insect IAPs (Fig. 1). Because virus infection, including that by AcMNPV, triggers a dramatic depletion of DIAP1 (6, 19), the molecular mechanisms involved are of comparative interest. We assessed the role of the DIAP1 leader in turnover by using Drosophila cells stably transfected with DIAP1T7 plasmids. Each stable DL-1 cell line responded normally to AcMNPV as indicated by the early synthesis of IE1 (Fig. 7B). As shown previously (35), endogenous DIAP1 was depleted and effector caspase DrICE was activated in parental cells, as indicated by the appearance of the DrICE large subunit (Fig. 7B, lanes 3 to 5). Overexpressed wild-type DIAP1T7 also disappeared rapidly during infection, even though DrICE activation was blocked (lanes 8 to 10). The N-terminal T7 tag did not affect stability or function (data not shown). Mutated DIAP1(D20A)T7 was depleted with similar kinetics (lanes 13 to 15). Because the D20A substitution eliminates caspase cleavage at DQVD20-N within the leader (Fig. 7A), depletion was caspase independent, confirming previous work (19).

FIG 7.

DIAP1 stability. (A) Structural organization. DIAP1 possesses a 44-residue leader, two BIRs, and a C-terminal RING. Asp20 and Ile393 are required for caspase cleavage and ubiquitin ligase activity, respectively. Addition of the N-terminal T7 epitope tag has no effect on stability or function (data not shown). (B) Virus-induced instability. Parental DL-1 cells or cells stably expressing wild-type (wt), D20A- or M1L-mutated (M1KO) DIAP1T7 were mock infected (mi) or inoculated (virus) with AcMNPV. SDS-lysates prepared at the indicated times (in hours) thereafter were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-DIAP1, anti-DrICE, anti-IE1, or anti-actin. nd, not done. M38-initiated DIAP1 is marked (closed arrow). (C) Chimeric Op-IAP3T7. The leader of OpIAP (wt) was replaced with the first 36 residues (DL) of DIAP1 to generate Op-IAP3DL. (D) Stability assays. SF21 cells transfected 24 h earlier with plasmids encoding T7-tagged wild-type (wt) and chimeric Op-IAP3DL were lysed at the indicated times after cycloheximide (CHX) treatment and subjected to anti-T7 immunoblot analysis; a representative experiment is shown. (E) Half-lives. The half-lives (in minutes) ± the standard deviations of Op-IAP3T7 with or without the DIAP1 leader (DL) were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

In DIAP1-overexpressing cells, a smaller but prominent DIAP1 fragment (arrow) appeared resistant to virus-induced depletion (Fig. 7B, lanes 6 to 10 and lanes 11 to 15). On the basis of size, we suspected that this fragment was produced by internal initiation at Met38 (Fig. 7A). We therefore generated a cell line that overproduced DIAP1T7(M1KO) in which Met1 was eliminated to force initiation at Met38. Comparable in size to the DIAP1-related fragment, DIAP1T7(M1KO) was resistant to depletion (Fig. 7B, lanes 18 to 20) and blocked viral apoptosis (data not shown). We concluded that the DIAP1 leader mediated caspase-independent turnover but was dispensable for antiapoptotic activity. To confirm that the DIAP1 leader caused instability, we replaced the leader of highly stable Op-IAP3 with the N-terminal 36 residues of DIAP1 (Fig. 7C). In transfected lepidopteran (SF21) cells, chimeric Op-IAPDL was turned over 12 times faster than wild-type Op-IAP3 (Fig. 7D and E).

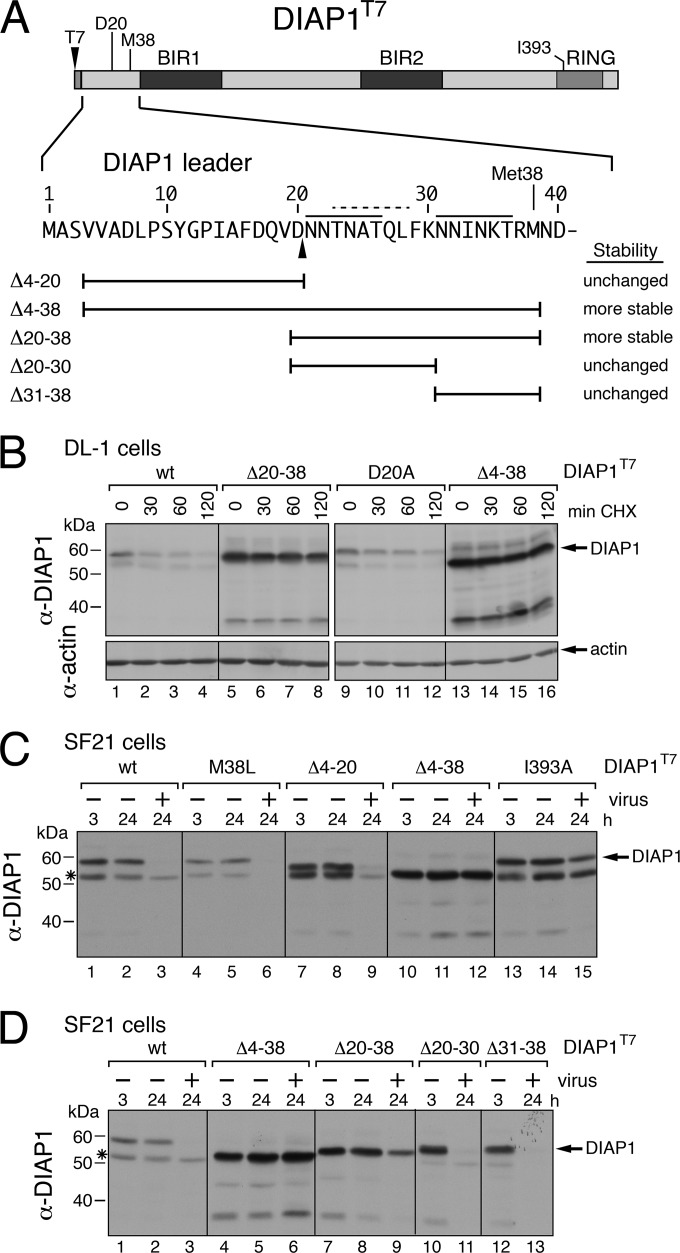

The DIAP1 leader has a unique instability element.

We next mapped residues within DIAP1 that contributed to instability (Fig. 8A). As expected, removal of leader residues 4 to 38 increased the half-life and steady-state level of DIAP1(Δ4-38)T7 in stably transfected DL-1 cells (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 1 to 4 and lanes 13 to 16). Deletion of leader residues 20 to 38 (lanes 5 to 8) also increased stability, whereas removal of residues 4 to 20 (see below) or the substitution D20A did not (lanes 9 to 12). Thus, DIAP1 residues 21 to 38 comprise a degron.

FIG 8.

DIAP1 instability motifs. (A) Deletions. DIAP1 leader residues (bars) were replaced with Gly-Ser; the stability (right) of each deletion is compared to that of wild-type (wt) DIAP1T7. (B) Stability assay. Drosophila DL-1 cells stably transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated DIAP1T7 were lysed at the indicated times (in minutes) after CHX treatment and subjected to anti-T7 immunoblot analysis; the results from a representative experiment are shown. (C and D) Virus-induced DIAP1 instability. SF21 cells transfected 24 h earlier with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated DIAP1T7 were mock infected (−) or inoculated (+) with AcMNPV, lysed at the indicated times (in hours) thereafter, and analyzed as described in panel B.

To further investigate the degron, we tested DIAP1's stability in heterologous lepidopteran cells during baculovirus infection. Full-length DIAP1T7 was depleted by 24 h after infection (Fig. 8C, lanes 1 to 3). In contrast, leaderless DIAP1(Δ4-38)T7 (lanes 10 to 12) and RING-defective I393A-mutated DIAP1T7 were stabilized. Thus, the DIAP1 leader and RING confer instability in insect species of different taxonomic orders. Because removal of residues 4 to 20 had no effect on depletion (Fig. 8C, lanes 7 to 9), we tested residues in the C-terminal half of the leader. Removal of residues 20 to 38 increased DIAP1 stability in infected SF21 cells (Fig. 8D, lanes 7 to 9). However, deletion of residues 20 to 30 or 31 to 38 had no effect, as DIAP1(Δ20-30)T7 and DIAP1(Δ31-38)T7 were turned over rapidly (Fig. 8D, lanes 10 to 13). Thus, a degron encompassing residues 21 to 38 confers virus-induced DIAP1 instability. We concluded that the leader-embedded degrons of dipteran and lepidopteran IAPs are distinct from one another.

DISCUSSION

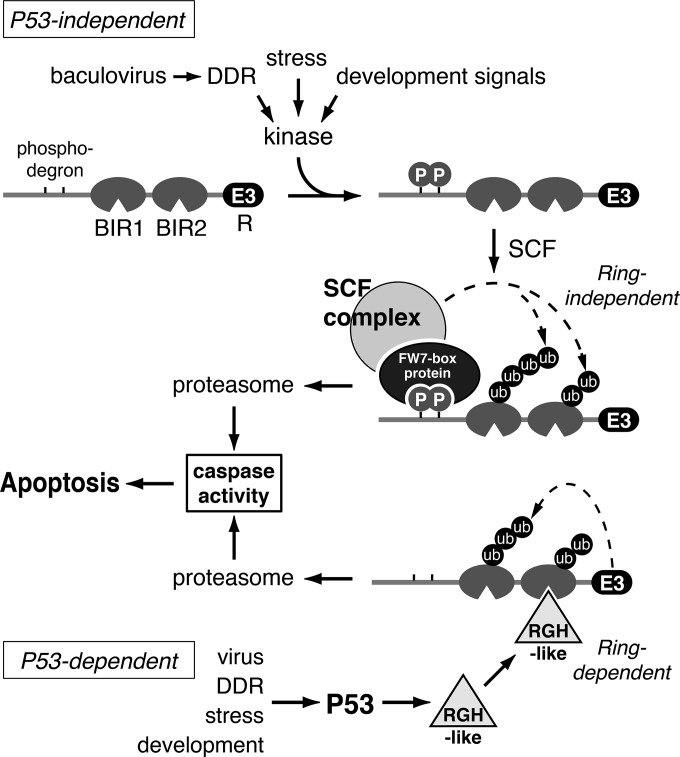

IAPs play an important role in insect innate immunity by triggering apoptosis when their intracellular levels reach a critical threshold. Thus, the molecular mechanisms that regulate IAP levels also determine the fate of pathogen-infected cells. We report here that insect IAPs, including those of lepidopteran and dipteran species, possess novel degradative motifs (degrons) embedded in their N termini that control IAP levels in response to cellular signals. In particular, we identified a phosphorylation-sensitive degron in lepidopteran IAPs that downregulates IAP levels, likely through SKP1/Cullin/F-box (SCF)-mediated degradation. A rapid, signal-responsive degron, which is independent of tumor suppressor P53, provides insects with an important pathway for antiviral self-destruction upon pathogen invasion.

The N-terminal phospho-degron of lepidopteran IAPs.

The 96-residue N-terminal leader of Spodoptera SfIAP contributes to rapid turnover of this critical IAP, including that induced by baculovirus infection (19, 20). In the present study, we show that leader-mediated SfIAP degradation is conferred by a phospho-degron, which is conserved in sequence and position among insect IAPs of the order Lepidoptera (Noctuidae). The SfIAP leader conferred instability, including that when physically linked to heterologous proteins, and thus satisfies the definition of a degron (44). For example, the half-life of viral Op-IAP3, which lacks a comparable leader, was dramatically shortened from 133 min to 21 min when fused to the SfIAP leader (Fig. 2C). Similarly, the leader shortened the life span of other proteins unrelated to IAP and lacking BIRs (R. Vandergaast and P. Friesen, unpublished data). When linked physically, the leader also stimulated phosphorylation of SfIAP and viral Op-IAP3 (Fig. 5). Leader-mediated hyperphosphorylation induced protein instability (Fig. 6). The N-terminal leader is thus necessary and sufficient for phosphorylation and enhanced turnover.

The SfIAP phospho-degron is composed of multiple elements, including the consensus TPxxS motif (Fig. 1). Dual phosphorylation of Thr and Ser (underlined) is usually required for interaction with the F-box protein component of an SCF complex, which mediates ubiquitination and subsequent degradation (43, 44). Consistent with the involvement of an SCF complex, leader-mediated turnover was independent of the E3 ligase within the SfIAP RING (Fig. 6A and D). Nonetheless, the RING also contributes to SfIAP turnover (Fig. 2A) and is required for its antiapoptotic activity (20). On the basis of sequence identity and tests with kinase inhibitors (Fig. 5B), it is likely that an MAPK-like kinase phosphorylates the degron (see below). MAPKs use substrate-docking sites that confer specificity of kinase binding (45, 46). Deletion of either of the two consensus MAPK docking motifs within the SfIAP leader increased protein stability (Fig. 3 and 4). The distal site (KKSGLQMDI, residues 11 to 19) was most influential in conferring protein instability during nonapoptotic conditions, whereas both the distal and proximal (KIRPLAPLML, residues 43 to 52) sites conferred the greatest instability upon virus infection. The proximal docking site was most important for phosphorylation; its deletion (SfIAPΔ29-52) abolished phosphorylation (Fig. 5). The TPxxS motif was not absolutely required for SfIAP phosphorylation (data not shown), probably because there exist redundant overlapping consensus sites for MAPK and GSK3 kinases within this Ser/Thr-rich domain (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the TPxxS motif, along with the kinase docking sites were required for maximum sensitivity to virus-induced turnover (Fig. 4). Future studies will identify which SfIAP residues are phosphorylated and the kinase(s) responsible.

Model for phosphoregulation of lepidopteran IAPs.

Our findings, combined with sequence predictions (Fig. 1), suggest that the SfIAP degron belongs to the family of SCF ubiquitin ligase-binding phospho-degrons that includes an FBW7-related F-box protein (43). Our model predicts that upon phosphorylation of the degron's TPxxS motif (Fig. 9), SfIAP binds to a SCFFBW7 complex through direct interaction with an FBW7 F-box protein, which functions in substrate recognition. As a result, SfIAP is ubiquitinated and degraded, thereby launching caspase-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 9). In a related possibility, leader-mediated phosphorylation could unveil a hidden degron, which upon unmasking promotes rapid degradation of the cellular IAP.

FIG 9.

Models for insect IAP turnover that triggers apoptosis. In the P53-independent pathway, a phospho-degron (TPxxS) within the IAP leader is activated by phosphorylation that is mediated by a stress- or DDR-activated kinase. A complex of SKP1/Cullin/F-box (SCF) recognizes the phosphorylated leader and ubiquitinates the bound IAP substrate, causing proteasome-mediated turnover, which initiates caspase-dependent apoptosis; signal-induced gene expression is not required. In the P53-dependent pathway, a variety of signals trigger activation of tumor suppressor P53, which in turn induces transcription of proapoptotic factors, analogous to Drosophila Reaper/Grim/Hid (RGH-like). RGH association with IAP through the BIRs induces RING-dependent ubiquitination and subsequent proteasome degradation of the IAP that leads to apoptosis.

A signal-induced, kinase-activated pathway is mechanistically distinct from that involving newly synthesized proapoptotic factors, such as Reaper/Grim/Hid (RGH), which bind to IAP and promote IAP self-ubiquitination via the E3 ligase of the RING (Fig. 9). In invertebrates, RGH-promoted IAP turnover involves de novo gene expression, which requires transcriptional activation by P53 (reviewed in references 4, 5, 15, and 16). The failure of Spodoptera P53 to contribute to baculovirus-induced apoptosis (57), despite rapid IAP depletion, is consistent with our findings that suggest that phospho-degron-mediated IAP degradation is independent of P53 activity. Depletion of endogenous SfIAP in cell-free cytosolic extracts, which depends on the SfIAP leader and occurs without new protein synthesis (19), also suggests that de novo gene expression is dispensable. The capacity of the SfIAP leader to also promote depletion of heterologous proteins that lack IAP BIR motifs argues that turnover does not require RGH interaction (see above).

SCF-mediated turnover of insect growth regulators is well established. TPxxS phospho-degrons TPPAS and TPSDS regulate Drosophila cyclin E and dmyc (c-myc), respectively (58, 59). When phosphorylated, these degrons interact with the Drosophila F-box protein FBW7 (encoded by archipelago [ago]) and are degraded by the SCFago/FBW7 pathway. The SfIAP leader caused rapid turnover of SfIAP in transfected Drosophila DL-1 cells, as leaderless SfIAP was abundant but full-length SfIAP was not (R. Vandergaast, J. K. Mitchell, and P. D. Friesen, unpublished data). Thus, the SfIAP phospho-degron may also respond to Drosophila SCF complexes, including SCFago/FBW7. MAPK-mediated phosphorylation also negatively regulates the Drosophila proapoptotic factor Hid (encoded by head involution defective [hid]) (60). Hid-mediated killing is enhanced upon targeted mutation of potential phosphorylation sites within Hid (60), including those within a predicted FBW7-responsive phospho-degron TPRTS (R. Vandergaast and P. Friesen, unpublished). Loss of the phospho-degron may restrict Hid turnover, thereby enhancing Hid-mediated apoptosis. Because Hid and DIAP1 have opposing pro- versus antiapoptotic effects, it is not surprising that DIAP1 lacks an SCFFBW7-responsive phospho-degron (see below).

The DIAP1 degron.

Drosophila DIAP1 is also negatively regulated by phosphorylation. The IKK-related kinase DmIKKε promotes development-specific degradation of DIAP1 through an uncharacterized mechanism (25, 26). Our studies here indicated that the DIAP1 leader possesses a degron, which conferred protein instability during infection, under nonapoptotic conditions, and when fused to viral Op-IAP3 (Fig. 7 and 8). The degron mapped to DIAP1 leader residues 21 to 37 and acted independently of the caspase motif (DQVD20-N), which after cleavage initiates N-end rule E3 ligase-mediated degradation (61, 62). Although phosphorylation enhanced DIAP1 instability (Fig. 6B), the DIAP1 leader lacks a Ser/Thr-rich domain and bears minimal sequence similarity with the IAP leaders of moths or mosquitoes (Fig. 1). A low probability site (TNATQLF) for phosphorylation by phosphoinositide-3-OH-kinase (PI3K)-related kinases (48) is predicted within the DIAP1 degron (63). Because DDR signaling involves PI3K kinases, the DDR may also regulate DIAP1 levels (see below). Consistent with this possibility, DIAP1 is rapidly depleted and apoptosis is triggered when cultured Drosophila DL-1 cells are treated with etoposide, a topoisomerase inhibitor that causes DNA damage and activates the DDR (J. Mitchell and P. Friesen, unpublished data). Our data suggest that the DIAP1 degron recruits instability factors in response to pathogen signaling. One candidate is Drosophila Morgue, an F-box protein with ubiquitin conjugase activity that regulates DIAP1 levels (64, 65). Interestingly, the degron-containing DIAP1 leader negatively affects DIAP1 levels in heterologous lepidopteran (Spodoptera) cells (Fig. 8), suggesting that degron function may be conserved. Additional studies will define the DIAP1 degron identified here and its regulatory factors.

Signal-induced regulation of invertebrate cellular IAPs but not viral IAPs.

During infection, baculovirus DNA replication rapidly depletes SfIAP and DIAP1 in Spodoptera and Drosophila cells, respectively (19, 22). Inhibition of the host DDR blocks virus-induced destruction of these IAPs and thereby prevents apoptosis (22). These findings argue that the DDR, activated by virus DNA replication, engages an antivirus defense path that degrades host IAPs and causes apoptosis (Fig. 9). Our study suggests that the Spodoptera DDR activates an MAPK-like kinase responsible for phospho-degron-mediated SfIAP degradation. Moreover, what is unique here is that DDR-initiated apoptosis does not require the participation of P53 and subsequent gene activation. Because of the link between the DDR and IAP destruction, the identity of the kinase(s) responsible is of significant interest. MAPK kinases orchestrate many cell signaling pathways, including those regulating innate immunity, apoptosis, stress, and the DDR (reviewed by references 47, 48–50). In vertebrates, the DDR can activate MAPK, including p38 (48, 49). Thus, MAPK regulation of phospho-degron-mediated turnover of SfIAP is consistent with a role in antiviral defense triggered by the DDR. A major implication of our study is that insects have multiple mechanisms by which cellular IAPs are actively destroyed, including a kinase-mediated, signal-induced pathway that does not require de novo protein synthesis. Such a proapoptotic path, independent of P53 and its activation of RGH factors, would provide insects with a swift antivirus response.

Most viral IAPs, including those encoded by baculoviruses (Fig. 1), entomopoxviruses, iridoviruses, and African swine fever virus, have short leaders that precede the first BIR and thus lack leader-embedded degrons. The absence of N-terminal leaders on viral IAPs emphasizes the important role for the degron in control of IAP levels. Presumably, each of these insect DNA viruses must replicate their DNA genome in the face of an activated host DDR. Thus, the absence of DDR-responsive degradation signals would provide enhanced viral IAP stability and thus more potent antiapoptotic activity compared to cellular IAPs. Our findings continue to support the simple possibility that viral IAPs evolved from cellular IAPs (66) in a process that involved elimination of N-terminal signal response elements (20). Additional studies promise to provide insight into this unique aspect of insect virus evolution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rebecca Cerio, Duy Tran, and Erik Settles for reagents and helpful discussions.

This study was supported in part by Public Health Service grants AI25557 and AI40482 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P.D.F.) and National Institutes of Health Predoctoral Traineeship T32 GM07215 (R.V. and J.K.M.) and T32 AI078985 (N.M.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Orme M, Meier P. 2009. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in Drosophila: gatekeepers of death. Apoptosis 14:950–960. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srinivasula SM, Ashwell JD. 2008. IAPs: what's in a name? Mol Cell 30:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumble JM, Duckett CS. 2008. Diverse functions within the IAP family. J Cell Sci 121:3505–3507. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gyrd-Hansen M, Meier P. 2010. IAPs: from caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF-κB, inflammation, and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 10:561–574. doi: 10.1038/nrc2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Riordan MX, Bauler LD, Scott FL, Duckett CS. 2008. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in eukaryotic evolution and development: a model of thematic conservation. Dev Cell 15:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Settles EW, Friesen PD. 2008. Flock house virus induces apoptosis by depletion of Drosophila inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein DIAP1. J Virol 82:1378–1388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01941-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Igaki T, Yamamoto-Goto Y, Tokushige N, Kanda H, Miura M. 2002. Down-regulation of DIAP1 triggers a novel Drosophila cell death pathway mediated by Dark and DRONC. J Biol Chem 277:23103–23106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muro I, Hay BA, Clem RJ. 2002. The Drosophila DIAP1 protein is required to prevent accumulation of a continuously generated, processed form of the apical caspase DRONC. J Biol Chem 277:49644–49650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang SL, Hawkins CJ, Yoo SJ, Muller HA, Hay BA. 1999. The Drosophila caspase inhibitor DIAP1 is essential for cell survival and is negatively regulated by HID. Cell 98:453–463. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pridgeon JW, Zhao L, Becnel JJ, Strickman DA, Clark GG, Linthicum KJ. 2008. Topically applied AaeIAP1 double-stranded RNA kills female adults of Aedes aegypti. J Med Entomol 45:414–420. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/45.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Q, Clem RJ. 2011. Defining the core apoptosis pathway in the mosquito disease vector Aedes aegypti: the roles of iap1, ark, dronc, and effector caspases. Apoptosis 16:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0558-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crook NE, Clem RJ, Miller LK. 1993. An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J Virol 67:2168–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birnbaum MJ, Clem RJ, Miller LK. 1994. An apoptosis-inhibiting gene from a nuclear polyhedrosis virus encoding a polypeptide with Cys/His sequence motifs. J Virol 68:2521–2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mace PD, Shirley S, Day CL. 2010. Assembling the building blocks: structure and function of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Cell Death Differ 17:46–53. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broemer M, Meier P. 2009. Ubiquitin-mediated regulation of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol 19:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hay BA, Guo M. 2006. Caspase-dependent cell death in Drosophila. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22:623–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012804.093845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaux DL, Silke J. 2005. IAPs, RINGs and ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:287–297. doi: 10.1038/nrm1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann KC, Ricci JE, Droin NM, Green DR. 2002. The role of ARK in stress-induced apoptosis in Drosophila cells. J Cell Biol 156:1077–1087. doi: 10.1083/jcb.20112068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandergaast R, Schultz KL, Cerio RJ, Friesen PD. 2011. Active depletion of host cell inhibitor-of-apoptosis proteins triggers apoptosis upon baculovirus DNA replication. J Virol 85:8348–8358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00667-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerio RJ, Vandergaast R, Friesen PD. 2010. Host insect inhibitor-of-apoptosis SfIAP functionally replaces baculovirus IAP but is differentially regulated by Its N-terminal leader. J Virol 84:11448–11460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01311-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hozak RR, Manji GA, Friesen PD. 2000. The BIR motifs mediate dominant interference and oligomerization of inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP. Mol Cell Biol 20:1877–1885. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.5.1877-1885.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell JK, Friesen PD. 2012. Baculoviruses modulate a proapoptotic DNA damage response to promote virus multiplication. J Virol 86:13542–13553. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02246-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brodsky MH, Nordstrom W, Tsang G, Kwan E, Rubin GM, Abrams JM. 2000. Drosophila p53 binds a damage response element at the reaper locus. Cell 101:103–113. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryoo HD, Bergmann A, Gonen H, Ciechanover A, Steller H. 2002. Regulation of Drosophila IAP1 degradation and apoptosis by reaper and ubcD1. Nat Cell Biol 4:432–438. doi: 10.1038/ncb795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koto A, Kuranaga E, Miura M. 2009. Temporal regulation of Drosophila IAP1 determines caspase functions in sensory organ development. J Cell Biol 187:219–231. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuranaga E, Kanuka H, Tonoki A, Takemoto K, Tomioka T, Kobayashi M, Hayashi S, Miura M. 2006. Drosophila IKK-related kinase regulates nonapoptotic function of caspases via degradation of IAPs. Cell 126:583–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenev T, Ditzel M, Zachariou A, Meier P. 2007. The antiapoptotic activity of insect IAPs requires activation by an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell Death Differ 14:1191–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herman-Bachinsky Y, Ryoo HD, Ciechanover A, Gonen H. 2007. Regulation of the Drosophila ubiquitin ligase DIAP1 is mediated via several distinct ubiquitin system pathways. Cell Death Differ 14:861–871. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaughn JL, Goodwin RH, Tompkins GJ, McCawley P. 1977. The establishment of two cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera; Noctuidae). In Vitro 13:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02615077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider I. 1972. Cell lines derived from late embryonic stages of Drosophila melanogaster. J Embryol Exp Morphol 27:353–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hershberger PA, Dickson JA, Friesen PD. 1992. Site-specific mutagenesis of the 35-kilodalton protein gene encoded by Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: cell line-specific effects on virus replication. J Virol 66:5525–5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaCount DJ, Hanson SF, Schneider CL, Friesen PD. 2000. Caspase inhibitor P35 and inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP block in vivo proteolytic activation of an effector caspase at different steps. J Biol Chem 275:15657–15664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell JK, Byers NM, Friesen PD. 2013. Baculovirus F-box protein LEF-7 modifies the host DNA damage response to enhance virus multiplication. J Virol 87:12592–12599. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02501-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cartier JL, Hershberger PA, Friesen PD. 1994. Suppression of apoptosis in insect cells stably transfected with baculovirus p35: dominant interference by N-terminal sequences p35(1-76). J Virol 68:7728–7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lannan E, Vandergaast R, Friesen PD. 2007. Baculovirus caspase inhibitors P49 and P35 block virus-induced apoptosis downstream of effector caspase DrICE activation in Drosophila melanogaster cells. J Virol 81:9319–9330. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00247-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson VA, Wetter JA, Friesen PD. 2001. Oligomerization mediated by a helix-loop-helix-like domain of baculovirus IE1 is required for early promoter transactivation. J Virol 75:6042–6051. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6042-6051.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taggart DJ, Mitchell JK, Friesen PD. 2012. A conserved N-terminal domain mediates required DNA replication activities and phosphorylation of the transcriptional activator IE1 of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. J Virol 86:6575–6585. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00373-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Gort T, Boyle DL, Clem RJ. 2012. Effects of manipulating apoptosis on Sindbis virus infection of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. J Virol 86:6546–6554. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00125-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK. 2003. The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell 114:457–467. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pantalacci S, Tapon N, Leopold P. 2003. The Salvador partner Hippo promotes apoptosis and cell-cycle exit in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol 5:921–927. doi: 10.1038/ncb1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinberg TH, Agnew BJ, Gee KR, Leung WY, Goodman T, Schulenberg B, Hendrickson J, Beechem JM, Haugland RP, Patton WF. 2003. Global quantitative phosphoprotein analysis using Multiplexed Proteomics technology. Proteomics 3:1128–1144. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welcker M, Clurman BE. 2008. FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: a tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat Rev Cancer 8:83–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. 2008. Diversity of degradation signals in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:679–690. doi: 10.1038/nrm2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharrocks AD, Yang SH, Galanis A. 2000. Docking domains and substrate-specificity determination for MAP kinases. Trends Biochem Sci 25:448–453. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biondi RM, Nebreda AR. 2003. Signalling specificity of Ser/Thr protein kinases through docking-site-mediated interactions. Biochem J 372:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. 2007. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 26:3279–3290. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bensimon A, Aebersold R, Shiloh Y. 2011. Beyond ATM: the protein kinase landscape of the DNA damage response. FEBS Lett 585:1625–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Y, Li N, Xiang R, Sun P. 2014. Emerging roles of the p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in oncogene-induced senescence. Trends Biochem Sci 39:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monteiro F, Carinhas N, Carrondo MJ, Bernal V, Alves PM. 2012. Toward system-level understanding of baculovirus-host cell interactions: from molecular fundamental studies to large-scale proteomics approaches. Front Microbiol 3:391. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, Gallagher TF, Kumar S, Green D, McNulty D, Blumenthal MJ, Heys JR, Landvatter SW, et al. 1994. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature 372:739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeSilva DR, Jones EA, Favata MF, Jaffee BD, Magolda RL, Trzaskos JM, Scherle PA. 1998. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase blocks T cell proliferation but does not induce or prevent anergy. J Immunol 160:4175–4181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meijer L, Skaltsounis AL, Magiatis P, Polychronopoulos P, Knockaert M, Leost M, Ryan XP, Vonica CA, Brivanlou A, Dajani R, Crovace C, Tarricone C, Musacchio A, Roe SM, Pearl L, Greengard P. 2003. GSK-3-selective inhibitors derived from Tyrian purple indirubins. Chem Biol 10:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dounay AB, Forsyth CJ. 2002. Okadaic acid: the archetypal serine/threonine protein phosphatase inhibitor. Curr Med Chem 9:1939–1980. doi: 10.2174/0929867023368791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tettamanti G, Malagoli D. 2008. In vitro methods to monitor autophagy in Lepidoptera. Methods Enzymol 451:685–709. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu W, Wei W, Ablimit M, Ma Y, Fu T, Liu K, Peng J, Li Y, Hong H. 2011. Responses of two insect cell lines to starvation: autophagy prevents them from undergoing apoptosis and necrosis, respectively. J Insect Physiol 57:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang N, Wu W, Yang K, Passarelli AL, Rohrmann GF, Clem RJ. 2011. Baculovirus infection induces a DNA damage response that is required for efficient viral replication. J Virol 85:12547–12556. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05766-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moberg KH, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. 2001. Archipelago regulates cyclin E levels in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Nature 413:311–316. doi: 10.1038/35095068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moberg KH, Mukherjee A, Veraksa A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Hariharan IK. 2004. The Drosophila F box protein archipelago regulates dMyc protein levels in vivo. Curr Biol 14:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bergmann A, Agapite J, McCall K, Steller H. 1998. The Drosophila gene hid is a direct molecular target of Ras-dependent survival signaling. Cell 95:331–341. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ditzel M, Broemer M, Tenev T, Bolduc C, Lee TV, Rigbolt KT, Elliott R, Zvelebil M, Blagoev B, Bergmann A, Meier P. 2008. Inactivation of effector caspases through nondegradative polyubiquitylation. Mol Cell 32:540–553. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yan N, Wu JW, Chai J, Li W, Shi Y. 2004. Molecular mechanisms of DrICE inhibition by DIAP1 and removal of inhibition by Reaper, Hid and Grim. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nsmb764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dinkel H, Van Roey K, Michael S, Davey NE, Weatheritt RJ, Born D, Speck T, Kruger D, Grebnev G, Kuban M, Strumillo M, Uyar B, Budd A, Altenberg B, Seiler M, Chemes LB, Glavina J, Sanchez IE, Diella F, Gibson TJ. 2014. The eukaryotic linear motif resource ELM: 10 years and counting. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D259–D266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wing JP, Schreader BA, Yokokura T, Wang Y, Andrews PS, Huseinovic N, Dong CK, Ogdahl JL, Schwartz LM, White K, Nambu JR. 2002. Drosophila Morgue is an F box/ubiquitin conjugase domain protein important for grim-reaper mediated apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 4:451–456. doi: 10.1038/ncb800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hays R, Wickline L, Cagan R. 2002. Morgue mediates apoptosis in the Drosophila melanogaster retina by promoting degradation of DIAP1. Nat Cell Biol 4:425–431. doi: 10.1038/ncb794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hughes AL. 2002. Evolution of inhibitors of apoptosis in baculoviruses and their insect hosts. Infect Genet Evol 2:3–10. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1348(02)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]