Abstract

Several new studies have documented high rates of sexual identity mobility among young adults, but little work has investigated the links between identity change and mental health. This study uses the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (N = 11,727) and employs multivariate regression and propensity score matching to investigate the impact of identity change on depressive symptoms. The results reveal that only changes in sexual identity toward more same-sex-oriented identities are associated with increases in depressive symptoms. Moreover, the negative impacts of identity change are concentrated among individuals who at baseline identified as heterosexual or had not reported same-sex romantic attraction or relationships. No differences in depressive symptoms by sexual orientation identity were found among respondents who reported stable identities. Future research should continue to investigate the factors that contribute to the relationship between identity change and depression, such as stigma surrounding sexual fluidity.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, identity development, LGBT, mental health, sexual orientation

A large body of research has shown that sexual minorities report poorer mental health functioning than sexual nonminorities, including higher rates of depression and depressive symptoms (Hatzenbuehler, Hilt, and Nolen-Hoeksema 2010; Marshal et al. 2011; Mustanski, Garofalo, and Emerson 2010). Most commonly, sexual orientation disparities in mental health are understood to be a function of the excess stress, discrimination, and victimization sexual minorities experience because of their stigmatized identity (D'Augelli, Pilkington, and Hershberger 2002; Feinstein, Goldfried, and Davila 2012; Hatzenbuehler 2009; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, et al. 2010; Hershberger and D'Augelli 1995; Meyer 1995, 2003). In many studies, however, measures of discrimination, victimization, and stigma do not fully account for observed differences in mental health by sexual orientation (Burton et al. 2013; Marshal et al. 2011; Matthews et al. 2002; McLaughlin et al. 2012; Russell and Joyner 2001). Consequently, lingering questions remain related to the mechanisms that lead to poorer mental health functioning among sexual minorities.

This study adds to the extant literature by conceptualizing sexual identity mobility—the process of changing sexual orientation identity over time, including changes to both a more same-sex-oriented identity and a less same-sex-oriented identity—as a stressful life event that may contribute to sexual orientation disparities in depression. Theories of sexual identity development (Cass 1979; Coleman 1982; Troiden 1988) characterize the period surrounding identity change as being associated with high levels of cognitive dissonance and increased risk for poor mental health functioning. More broadly, theories of social stress posit that life events that result in threats to, or losses of, social identities are particularly salient for individual mental health functioning (Brown and Harris 1989; Reynolds and Turner 2008; Thoits 2010). Thus, while changes in sexual orientation identities may ultimately reduce cognitive dissonance and improve an individual's well-being, they may also result in loss of social resources and social networks. In particular, for individuals who report moving toward more same-sex-oriented identities, such changes may be associated with increased exposure to stigma and discrimination. While several new studies have shown that identity mobility over the life course is fairly common (Diamond 2003; Katz-Wise 2014; Ott et al. 2011; Savin-Williams, Joyner, and Rieger 2012), little research has examined the health-related consequences of sexual identity mobility. What research does exist suggests that changes in sexual orientation over time may be an important and understudied stress pathway linking sexual minority status to poorer mental health functioning (Needham 2012; Rosario et al. 2006; Ueno 2010).

Using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), this study examines the relationship between sexual identity mobility during emerging adulthood and depressive symptoms. I use multivariate regression and propensity score matching to (1) assess whether identity mobility predicts depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood, (2) examine whether the effect of identity mobility is impacted by psychosocial stressors reported at baseline and at the time of follow-up, (3) determine whether the effect of identity mobility is moderated by sexual orientation reported at baseline, and (4) investigate the impact of change to a more same-sex-oriented identity on depressive symptoms and whether this effect varies by the propensity to report identity change.

By further explicating the relationship between sexual identity mobility and depressive symptoms, this research will help to identify a potential important risk factor for depression, that is, identity mobility, which may then provide evidence for developing prevention treatment programs that target a specific risk period and a mechanism for intervention.

BACKGROUND

Sexual Orientation Development and Identity Change

Sexual orientation development scholars in the late 1970s and the 1980s outlined several models that characterized the development of same-sex sexual orientation as occurring in stages, some of which increased the risk of mental health disorders (Cass 1979; Coleman 1982; Troiden 1988). Broadly, these models suggest that the development of same-sex sexual orientation begins with a stage of initial awareness or confusion regarding one's same-sex orientation. This initial stage is followed by a second stage during which individuals begin to internally accept or experiment with their same-sex attractions or orientation. In this stage, individuals may experience high levels of cognitive dissonance and psychological distress as they increasingly become aware of their same-sex orientation and begin to act on these feelings while maintaining a heterosexual identity. These feelings are eventually resolved in the final phase of development when a gay/lesbian identity is adopted that aligns with the individual's sexual and romantic relationships.

The traditional sexual identity development models put forth by Cass (1979), Troiden (1983), and Coleman (1982) have been criticized in recent years, however, for their linearity and for not recognizing within-group variation in the timing and patterns of sexual identity formation (Diamond 2000, 2008; Rosario et al. 2006; Savin-Williams et al. 2012; Savin-Williams and Ream 2006). Some individuals may repeatedly change sexual orientation identity over the life course, including towards a less same-sex-oriented identity (Diamond 2003; Katz-Wise 2014; Ott et al. 2011; Savin-Williams et al. 2012). Cultural shifts in representation of sexual minorities in popular media, the removal of homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and increasing political protections and civil rights may have facilitated the “coming-out” process for sexual minority adolescents and young adults in recent years (Morgan 2013:20; Savin-Williams 2005). These changes, coupled with the rise of “emerging adulthood” as a life stage, have extended the process of sexual orientation exploration and identity development among contemporary youth and young adults (Morgan 2013). Studies documenting the changes in sexual orientation development, however, have not been met with much research on the implications of such changes for sexual minorities’ well-being.

In the social stress literature, life events that involve threats to or loss of identities are thought to be particularly salient for mental health functioning (Brown and Harris 1989; Thoits 1991, 2010). Indeed, social identities are an important organizing feature of social life: they help individuals identify social support and peer networks, and through these interactions, they validate in-group norms and can provide individuals with meaning and a sense of purpose (C. Haslam et al. 2008; S. Haslam et al. 2009). In particular, for minority populations, social identities and interactions with similarly identified persons are critical for validating in-group norms within a broader social context that seeks to invalidate their identities. Previous research has shown that identity stability (Bonanno, Papa, and O'Neill 2001; C. Haslam et al. 2008; Iyer and Jetten 2011) and identity commitment among racial-ethnic minorities (Iyer et al. 2009; Schnittker and McLeod 2005; Sellers et al. 2003, 2006) are protective factors for health and well-being.

Changes in identity are often motivated by the desire to improve mental health by reducing stress associated with discrepancies between the normative expectations associated with an identity standard and an individual's evaluation of his or her performance of the standard (Burke 2006); however, these changes may be fraught with stress themselves. To quote Burke (2006:92), “identity change involves changes in the meaning of the self: changes in what it means to be who one is as a member of a group, who one is in a role, or who one is as a person.” Thus, identity change may produce psychological strain due to disruptions in conceptions of the self but also due to material losses of social resources and support.

Sexual Identity Mobility and Mental Health

Forming a sexual identity is a difficult process for adolescents and young adults in general; however, for sexual minorities, this process often occurs within a larger heteronormative social and cultural context, which has important implications for their mental health (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2010; Rostosky et al. 2009; Wilkinson and Pearson 2009). Thus, while changes in sexual orientation identities may provide individuals with a new set of social resources and reduce cognitive dissonance, there may be a transitional period surrounding the time of identity change that is associated with psychological distress, in particular for individuals reporting more same-sex-oriented identities due to potential rejection and isolation from parents, peers, and former social identity group members (Corrigan and Matthews 2003; D'Augelli and Grossman 2001; Griffith and Hebl 2002; Rosario, Schrimshaw, and Hunter 2009).

A large body of research has shown that while mental health antecedents for sexual minorities are broadly similar to those of sexual nonminorities (Eccles et al. 2004), sexual minorities are more likely to report a variety of risk factors for depression than their heterosexual peers, including victimization, discrimination, poorer self-esteem (D'Augelli et al. 2002; Feinstein et al. 2012; Hatzenbuehler 2009; Hatzenbuehler, Hilt, et al. 2010; Hershberger and D'Augelli 1995; Meyer 1995, 2003). More recently, several studies have demonstrated the importance of the social environment for shaping sexual minority health (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, et al. 2010). Certain characteristics of the neighborhood and school environment that are associated with more or less homophobic attitudes, such as conservative political views, percentage of college degrees, and percentage in rural areas, have been shown to have important implications for the mental health of sexual minorities (Bell and Valentine 1995; Everett 2013; Kosciw, Greytak, and Diaz 2009; Wilkinson and Pearson 2009). Persons living in politically conservative social environments may be exposed to higher levels of stigma that negatively affect their mental health but may also influence the timing and pattern of identification with a sexual minority identity. Conversely, new research has shown that sexual minorities who reside in neighborhoods with higher levels of same-sex couples are associated with fewer depressive symptoms compared to neighborhoods that have no same-sex couples (Everett 2013).

Changes in sexual orientation identity may also be more or less punitive for mental health depending on the extent to which individuals have integrated other aspects of their sexual orientation into their lives. Indeed, the relevance of, or commitment to, an identity may determine the extent to which an identity change process produces psychological distress (Burke and Reitzes 1981; Burke and Stets 1999; Stryker and Serpe 1982). For example, the cognitive dissonance stemming from maintaining an exclusively heterosexual identity while experiencing same-sex romantic attraction or sexual behaviors triggers identity control systems to realign with a new identity in order to improve mental health. Some work has shown that the transition from heterosexual to a gay/lesbian identity is done to eliminate dissonance between identity and behavior (Higgins 2002). Alternatively, individuals who do not report same-sex attraction, behavior, or relationships may be earlier in the sexual identity development process and, therefore, have lower levels of identity commitment or fewer positive feelings about their sexual minority identity (Floyd and Stein 2002; Rosario et al. 2006; Rosario, Schrimshaw, and Hunter 2011).

Accounting for differences in baseline depressive symptoms and sexual minority status as well as exposure to psychosocial stressors pre– and post–identity change is important for determining the effect of identity change on mental health. One approach is to control for potential confounding factors and use interactions to address whether the effect of identity change varies by the existence of other sexual minority status indicators, such as same-sex romantic attraction, sexual orientation identity, and previous same-sex sexual behaviors. To account for all of the possible variations, however, this approach would require numerous interactions that result in an overspecified model. An alternative approach is to employ propensity score matching, which advances traditional generalized linear models (GLMs) by allowing researchers using observational data to simulate the conditions of a randomized trial. Capitalizing on the counterfactual framework (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983, 1984; Rubin 1997), propensity score matching estimates the probability of treatment assignment accounting for differences in all potential confounding variables that influence the probability of “treatment” (identity change) as well as the outcome variable (depressive symptoms). Using this approach allows one to simultaneously account for these factors and compare the effect of identity change on mental health only between those individuals with similar probabilities of reporting identity change. This approach advances GLMs in two important ways: First, it simultaneously accounts for differences across multiple indicators of sexual minority status at baseline (identity, attraction, behavior) as well as other confounding factors (e.g., social environment, victimization) both pre–identity change as well as post–identity change. Second, this approach restricts comparisons of identity change to those with similar propensities to experience the event, reducing potential selection biases in observational data used to make population-level inferences.

The few studies that have examined the effects of sexual identity mobility on well-being suggest that changes in identity are associated with mental health–related risk factors. Rosario and colleagues (2006) found that in a sample of 156 self-identified bisexual, gay, and lesbian young adults, respondents who consistently reported a gay/lesbian identity were more likely to be involved in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community activities and events and had more positive attitudes about their sexual orientation than respondents who changed their identity between the two waves of data collection. Rosario's sample, however, was not nationally representative and was limited to individuals who identified as bisexual, gay, or lesbian at the onset of data collection. Thus, this study was unable to assess the relationship between identity change and mental health among initially heterosexual-identified persons, a population in which the impact of identity change on mental health may be the largest.

Previous studies using Add Health data have repeatedly found that sexual minorities are more likely to report poorer mental health (Consolacion, Russell, and Sue 2004; Galliher, Rostosky, and Hughes 2004; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, and Xuan 2012; Russell and Consolacion 2003; Russell and Joyner 2001), but only two have examined how changes in sexual orientation over time influence mental health. Ueno (2010) found that women who reported same-sex sexual experiences in both adolescence and young adulthood also had more negative changes in depressive symptoms and that entry into same-sex sexual experience in adulthood was associated with negative changes in depression between adolescence and young adulthood for both men and women. A more recent study, using latent growth curve models, assessed the effect of attraction trajectories on mental health and found that transitions to same- or both-sex attraction were associated with more depressive symptoms and risk of suicidal thought for women but not men (Needham 2012). Both of these studies highlight the unique stress and mental health risks associated with transitions to a stigmatized sexual orientation. No research to date, however, has examined how changes in sexual orientation identity are linked to mental health or how such changes may be moderated by sexual orientation at baseline.

Aims

While there are multiple indicators of sexual orientation (e.g., attraction, sexual behavior, romantic relationships), all of which may change over time, mobility of sexual orientation identity may be unique in its potential implications for mental health. For minority populations, social identities help locate peers and social support networks that can buffer against sources of discrimination and stigma (Mossakowski 2003; Ramirez-Valles et al. 2010; Rosario et al. 2006). Previous work has gone so far as to suggest that in order for a stressful life event to have an effect on an individual's mental health, it requires a threat to, or loss of, a social identity (Thoits 2010). Thus, while it is well established that sexuality orientation is a multifaceted and dynamic process that occurs over the life course (Diamond 2003; Katz-Wise 2014; Ott et al. 2011; Savin-Williams et al. 2012), much less work has examined the effects of sexual identity mobility on mental health. Existing research, however, suggests that changes in sexual orientation, particularly, those transitions associated with more same-sex-oriented sexuality, may be linked to poorer mental health functioning. This paper addresses existing gaps by using nationally representative longitudinal data to explore the following research questions:

Do persons who change their sexual orientation identity during emerging adulthood report more depressive symptoms than persons who report a stable identity over time, and does the effect vary by the direction of identity change (toward a more same-sex-oriented identity or less same-sex-oriented identity)?

Is the relationship between identity mobility and depressive symptoms explained by increased exposure to psychosocial stressors (individual, interpersonal, and neighborhood level) reported at baseline and at the time of follow-up?

Does the effect of identity change on depressive symptoms vary by baseline indicators of sexual orientation?

Focusing exclusively on changes to more same-sex-oriented identities, what is the effect of identity change on depressive symptoms, and does it vary by the propensity to report an identity change?

DATA AND METHODS

This study used data from Waves 3 and 4 of the Add Health study. The Add Health study began in the fall of 1994 and involves a nationally representative, longitudinal sample of U.S. adolescents. The initial Add Health sample was drawn from 80 high schools and 52 middle schools throughout the United States, with unequal probabilities of selection (Harris et al. 2009; Harris, Halpern, and Whitsel 2004). The first wave of the Add Health study surveyed 90,118 adolescents who filled out a brief in-school survey. A subsample of students (n = 20,747) and their parents were asked to fill out an additional in-depth home interview survey. High school seniors in Wave 1 of Add Health were not selected for follow-up for Wave 2 but were reclaimed for the Wave 3 sample. Response rates for this survey were 79% for Wave 1, and 77.4% for Wave 3. Wave 4 of the Add Health survey, collected between 2007 and 2008, interviewed 80.3% of the eligible respondents. Because sexual orientation identity measures were only asked in Waves 3 and 4 of the Add Health survey, the sample was limited to these waves of data collection. Ages ranged from 18 to 26 in Wave 3 and 25 to 33 in Wave 4.

Sample

The sample was restricted to respondents who were interviewed at both Waves 3 and 4 of the survey and whose responses contained data on depressive symptoms for both waves (N = 12,209). From this sample, respondents who refused to answer the sexual orientation identity question (n = 44, Wave 3; n = 29, Wave 4), reported “don’t know” (n = 15, Wave 3; n = 12, Wave 4), or reported they were “not sexually attracted to either males or females” (n = 45, Wave 3; n = 44, Wave 4) were also excluded (N = 12,021). An additional 3% of eligible respondents were excluded because of missing information on key covariates, resulting in a total eligible sample size of 11,727. For the portion of the analysis that focused strictly on identity changes toward more same-sex-oriented identities, the sample excluded persons who changed their identity toward less same-sex-oriented identities, resulting in a sample size of 11,243.

Measures

Identity Change

The main independent variable of interest was change in sexual orientation identity between Waves 3 and 4 of the Add Health survey. The Add Health survey asked respondents to identify their sexual orientation along a five-point scale: exclusively heterosexual (straight) = 1; mostly heterosexual = 2; bisexual = 3; mostly gay/lesbian = 4; and exclusively gay/lesbian = 5. These questions were asked at both Waves 3 and 4 of the survey. A series of three dummy variables was created to examine the relationship between change in identity and mental health. One variable was created to measure change in sexual orientation identities toward more same-sex-oriented identities (7.37%), and one variable was created that measured whether individuals reported a less same-sex-oriented identity at Wave 4 than was reported at Wave 3 (4.41%).1 A final variable measured whether respondents reported the same identity at Waves 3 and 4 (referent; 88.2%). In the propensity score matching portion of the analysis, a single dummy variable was used that measured whether respondents changed their identity toward a more same-sex-oriented identity (7.7%; treatment = 1) or did not (control/stable group = 0).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured at Waves 3 and 4 using a five-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Perreira et al. 2005; Radloff 1977). This measure was constructed from a series of five questions that asked respondents, “How often was each of the following things true in the past seven days: you were bothered by things that don't usually bother you; you could not shake off the blues; you had trouble keeping your mind on what you were doing; you felt depressed; you felt sad.” Respondent answers for each question ranged from 0 = never to 4 = very often. Previous research has demonstrated that the shortened 5-item CES-D scale is valid and more appropriate for cross-cultural comparisons than the 19-item scale (Perreira et al. 2005). The scale ranges from 0 to 20 and has a Chronbach's alpha of .79 at Wave 4 and .82 at Wave 3.

Psychosocial Stressors

Physical victimization in the previous 12 years was measured at Waves 3 and 4 of the survey. Physical victimization was measured at Waves 3 and 4 and coded as a binary variable that measures “which of the following things happened in the last month: someone pulled a knife or gun on you; someone shot or stabbed you; someone slapped, hit, choked, or kicked you; you were beaten up.” Respondents who reported at least one of these incidents were coded as being victimized in the last 12 months (1) or not (0; referent).

Self-esteem was measured at Wave 3 using a series of questions that asked respondents, “Do you disagree or agree that you have many good qualities; you have a lot to be proud of; you like yourself just the way you are; you feel you are doing things just about right?” Responses ranged from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. The scale was summed and ranged from 4 to 20 and had a Cronbach's alpha of .78, with higher scores indicating poorer self-esteem.

Perceived discrimination was measured in Wave 4 with the question, “In your day-to-day life, how often do you feel you are treated with less respect or courtesy than other people?” A dichotomous variable was created that captures whether respondents report being treated with less respect never or rarely (referent) versus sometimes or often.

Several measures of the neighborhood environment were included in the analysis that may influence sexual orientation development patterns as well as mental health outcomes. During the time of in-home interviews, GPS coordinates were taken at the respondents’ households at Wave 3 (Swisher 2008) and Wave 4 (Morales and Monbureau 2013) and then linked to a variety of contextual-level data sources (e.g., the U.S. Census, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and election results).2 The percentage of Republican voters in the respondent's neighborhood was derived from county-level data on proportion of voters that voted for the Republican gubernatorial candidate in 2001 (Wave 3) matched to GPS coordinates for a respondent's county (Fowler and Monbureau 2010). The measure was coded into a series of dummy variables that measure whether a respondent's neighborhood comprises 0% to 32%, 33% to 65%, or 66% or more Republican voters.3 Percentage of college degrees in a respondent's neighborhood was derived from U.S. Census tract–level information on the proportion of individuals over the age of 25 who had college degrees that was GPS matched to a respondent's census tract at Waves 3 and 4. The measure ranged from 0% to 100%. Similarly, percentage of poverty also came from the census tract–level information on the percentage of individuals in a respondent's neighborhood that fell under U.S. government poverty thresholds; the measure ranged from 0% to 100%.

A measure of the percentage of same-sex couples from the U.S. Census was GPS matched to respondents’ census tract at Waves 3 and 4. Because of the very small range of the variable (0% to 8%), this variable was coded into a series of dummy variables that captured whether respondents lived in an area with 0% same-sex couples (referent), > 0% to < 2% same-sex couples, or ≥ 2% to 8% same-sex couples.

Sexual Orientation at Baseline (Wave 3)

A measure of romantic attraction was derived from two questions that asked respondents to identify whether they had ever been romantically attracted to a male and if they had ever been romantically attracted to a female. These questions were asked of both male and female respondents and were included in both Waves 3 and 4 of the Add Health data. From these two items, measures were created that captured whether respondents reported same-sex romantic attraction (1) or opposite-sex only romantic attraction (referent).4

Romantic relationship was derived from a question that asked respondents if they had had a romantic relationship since the time of last interview and the sex of the romantic partner. From these questions, three dummy variables were created that measured whether respondents had not had a romantic relationship, had had opposite-sex-only romantic relationship(s) (referent), or had had at least one same-sex romantic relationship.

In Wave 4 of the Add Health, survey respondents were asked, “Considering all types of sexual activity, with how many male partners have you ever had sex before the age of 18?” and “Considering all types of sexual activity, with how many female partners have you ever had sex before the age of 18?” These questions were asked of both male and female respondents and allowed me to measure whether respondents reported having had same-sex sexual encounters before 18 or opposite-sex-only sexual encounters before 18 (referent) or no sexual encounters before 18.5

Sexual orientation identity reported at Wave 3 was measured using the sexual orientation identity item. A series of dummy variables was created to capture whether respondents identified as exclusively heterosexual (referent), mostly heterosexual, bisexual, or mostly gay/exclusively gay/lesbian.

Controls

Gender was coded as a dummy variable that measures whether respondents were female or male (referent). Race-ethnicity was coded as a series of dummy variables that measure whether respondents identified as non-Hispanic white (referent), non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, or other race. Age was coded as a continuous variable that ranged from 24 to 33 years of age. Education was coded as series of dummy variables that captured whether the respondent reported less than a high school degree, a high school degree or its equivalent, some college, or a college degree (referent).

Analytic Plan

A four-step analytic plan was used to examine the relationship between identity change and mental health. First, descriptive statistics were presented for the total sample and stratified by whether individuals reported the same sexual orientation identity between waves, reported a more same-sex-oriented identity between waves, or reported a less same-sex-oriented identity between waves. Bivariate tests were used to assess significant differences in means between stability in identity versus changes toward more same-sex-oriented identities as well as differences in means between stability in identity and changes toward less same-sex-oriented identities.

Second, negative binomial regression was used to examine the effect of identity change on depressive symptoms. Multivariate model-building techniques were used to test whether psychosocial stressors and other markers of sexual minority status affected the relationship between identity change and depressive symptoms. A series of interactions was included that tested whether the effects of identity change varied by sexual orientation identity, same-sex romantic attraction, and same-sex romantic relationship reported at baseline (Wave 3).6 Tests for multicollinearity using variance inflation factor estimates showed that there were no issues related to multicollinearity in the analyses.

Third, propensity score matching was used to further investigate the relationship between identity change toward a more same-sex-oriented identity and depressive symptoms. Under the counterfactual framework, treatment assignment could be estimated such that each observation had some probability of being assigned to the treatment group that is greater than 0 and less than 1, regardless of whether that person was treated or not to satisfy the strongly ignorable treatment assignment assumption. These probabilities, or propensity scores, estimated from logistic regression create a theoretical and methodological basis for matching observations. Once propensity scores were calculated, three different matching techniques (nearest neighbor, radius, and stratified) were used to derive average treatment effect (ATE) estimates of the effect of identity change on the depressive symptoms of interest as illustrated in Equation 1:

| (1) |

in which Y1 and Y0 are the outcomes (depressive symptoms) in the two counterfactual situations: identity change (treatment) and identity stability (control). I employed different matching techniques to test if ATE varies depending on the specificity of the match. Nearest neighbor without replacement matched respondents who reported identity change with respondents in the stable group whose propensity score is nearest to their own. All stable units that were not matched to a treated respondent were dropped. Radius matching is slightly more restrictive, as it specifies that treated respondents can be matched only to stable-group respondents who fall within a .10 standard deviation of the treated respondent's propensity score. Similar to nearest neighbor matching, all unmatched stable units were dropped. Stratified matching was also used as a matching strategy. This approach calculates the ATE within propensity score blocks. While this approach is less restrictive, it has several advantages: (1) because treated and stable-group respondents are matched within quartile blocks rather than respondent to respondent, fewer data are discarded, and (2) it is easier to obtain balance using this more robust technique.

Finally, I investigated how the effects of stability in identity or identity change toward a more same-sex-oriented identity on depression vary across propensity scores by including an interaction between the propensity score and identity change in a negative binomial regression predicting depressive symptoms at Wave 4. This model controlled for all covariates used in the previous negative binomial models (i.e., baseline depressive symptoms, psychosocial stressors, baseline sexual orientation, controls). Plotting the effect of identity change and identity stability on depressive symptoms as it moves across propensity to report change allows for the observation of potential heterogeneous effects of change compared to stability. All regression analyses were conducted using the “svy” commands in Stata 12.0, and propensity score analyses were conducted using the Pscore package in Stata (Becker and Ichino 2002).

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for all covariates used in the analysis for the total population and stratified by whether respondents remained stable in their sexual orientation between waves, changed toward a more same-sex-oriented identity, or changed toward a less same-sex-oriented identity. Twelve percent of the total sample reported a different sexual orientation identity between Waves 3 and 4, of which 70% changed their sexual orientation to a more same-sex-oriented identity. Supplementary analyses (not shown) showed that the majority of respondents who changed their identity between waves did so by only one point in the identity scale (e.g., mostly heterosexual to bisexual): only 14.1% of those who reported a more same-sex-oriented identity changed by two or more points in the identity scale, and only 8.8% of those who shifted toward a less same-sex-oriented identity did so by two or more identities. The descriptive statistics also show difference in several important covariates between respondents who change identities and those who report stable identities.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Total Sample and by Identity Change, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health 2001-2008, Waves 1, 3, and 4 (N = 11,727).

| Variable | Total Sample (N = 11,727) | Stable Subsample (n = 10,339) | More Same-Sex Oriented (n = 904) | Less Same-Sex Oriented (n = 484) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable sexual orientation identity between Waves 3 and 4 | 88.22 | |||

| Sexual orientation identity change between Waves 3 and 4 | ||||

| More same-sex oriented | 7.37 | |||

| Less same-sex oriented | 4.41 | |||

| Sexual orientation identity, Wave 3 | ||||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 89.77 | 94.71 | 85.58*** | — |

| Mostly heterosexual | 7.15 | 3.93 | 6.80** | 70.51*** |

| Bisexual | 1.62 | .47 | 3.69*** | 21.16*** |

| Gay/lesbian | 1.46 | .89 | 3.93 | 8.33*** |

| Depressive symptoms, Wave 3 | 2.30 | 2.21 | 2.97*** | 3.09*** |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, Wave 4 | 28.77 | 28.81 | 28.31 | 28.76 |

| Female | 50.81 | 47.50 | 78.72*** | 70.31*** |

| Male | 49.19 | 52.50 | 21.28*** | 29.69*** |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 65.43 | 64.48 | 72.16** | 74.90*** |

| Non-Hispanic black | 14.11 | 14.77 | 10.23** | 7.34*** |

| Hispanic | 11.44 | 11.61 | 10.76 | 9.81 |

| Other race-ethnicity | 9.02 | 9.14 | 6.85 | 7.95 |

| Education, Wave 3 | ||||

| Less than high school | 8.13 | 8.04 | 8.53 | 9.35 |

| High school graduate | 16.56 | 17.04 | 12.18** | 14.66 |

| Some college | 43.05 | 42.83 | 47.81 | 42.71 |

| College graduate | 32.26 | 32.09 | 31.48 | 33.28 |

| Psychosocial stressors | ||||

| Victimized, Wave 3 | 14.03 | 17.97 | 18.69 | 18.73* |

| Victimized, Wave 4 | 18.07 | 20.92 | 21.24 | 20.94 |

| Self-esteem, Wave 3 | 7.15 | 7.09 | 7.61** | 7.79*** |

| Discrimination, Wave 4 | 24.00 | 23.50 | 30.03** | 24.13 |

| Neighborhood-level measures | ||||

| Percentage Republican, Wave 3 | ||||

| ≤ 33 | 14.02 | 14.04 | 15.24 | 11.57 |

| > 33 to ≤ 66 | 67.98 | 67.59 | 70.46 | 71.61 |

| > 66 | 18.00 | 18.37 | 14.30* | 16.82 |

| Percentage under the poverty line, Wave 3 | 14.81 | 14.89 | 14.81 | 13.22* |

| Percentage with college degree, Wave 3 | 22.53 | 22.30 | 23.75 | 25.10 |

| Percentage under the poverty line, Wave 4 | 14.73 | 14.76 | 15.10 | 13.49* |

| Percentage with college degree, Wave 4 | 25.19 | 24.99 | 26.14 | 27.59* |

| Same-sex couples, Wave 3 | ||||

| Same-sex couples, .0% | 55.46 | 55.63 | 53.25 | 55.73 |

| Same sex couples, > 0% to < 2.0% | 37.66 | 37.73 | 36.42 | 38.40 |

| Same sex couples, 2.0% to 8.0% | 6.88 | 6.64 | 10.33* | 5.87 |

| Same-sex couples, Wave 4 | ||||

| Same-sex couples, .0% | 56.08 | 56.70 | 53.00 | 50.75 |

| Same-sex couples, > 0% to < 2.0% | 33.02 | 32.59 | 34.70 | 36.87 |

| Same-sex couples, 2.0% to 8.0% | 10.90 | 10.71 | 12.30 | 12.38 |

| Sexual minority indicators | ||||

| Sexual romantic attraction, Wave 3 | ||||

| Same-sex romantic attraction, Wave 3 | 9.42 | 5.35 | 20.35*** | 62.17*** |

| Opposite-sex-only romantic attraction | 90.58 | 82.99 | 79.65*** | 37.83*** |

| Sexual behavior before age 18 | ||||

| No sex before 18 | 32.39 | 33.57 | 26.22*** | 27.19 |

| Same-sex sex before 18 | 3.34 | 1.91 | 15.10*** | 11.69*** |

| Opposite-sex-only sex before 18 | 64.27 | 37.48 | 58.68*** | 61.12*** |

| Romantic relationships, Wave 3 | ||||

| No relationship | 15.28 | 15.81 | 12.48* | 12.01* |

| Same-sex relationship | 2.87 | 1.96 | 7.31*** | 12.86*** |

| Opposite-sex-only relationships | 81.85 | 83.74 | 80.21 | 75.13 |

| Depressive symptoms, Wave 4 | 2.57 | 2.47 | 3.56*** | 3.00** |

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001.

Compared to men, women were significantly more likely to report changes in identity between waves. This finding is in line with other work that has found that women have higher levels of sexual fluidity over the life course compared to men (Ott et al. 2011; Rosario et al. 2010). Respondents who reported an identity change had significantly higher mean levels of depressive symptoms at both Waves 3 and 4, higher mean scores on the self-esteem scale indicating poorer self-esteem, and larger percentages of respondents victimized at Wave 3 compared to those who reported a stable identity. Respondents who reported more same-sex-oriented identities were more likely to report discrimination at Wave 4. Unsurprisingly, respondents who reported changes in their identity, both toward more and less same-sex-oriented identity, were more likely to report same-sex romantic attraction and relationships at Wave 3 as well as same-sex sexual relationships before the age of 18 compared to respondents who reported stable identities.

Identity Change and Mental Health

Table 2 presents the coefficients for depressive symptoms regressed on change in sexual orientation identity. Model 1 controls for sociodemographic characteristics and depressive symptoms at baseline, Model 2 adds controls for psychosocial stressors and measures of the social environment, and Model 3 adds controls for other measures of sexual orientation at baseline. Models 4 through 6 include interactions between identity change and romantic attraction reported at Wave 3 (Model 4), romantic relationships reported at Wave 3 (Model 5), and sexual orientation identity at Wave 3 (Model 5). An interaction between sexual behavior and identity change was tested but was not significant and therefore not included in the final table.

Table 2.

Betas from Negative Binomial Regressions Examining the Effect of Identity Change on Depressive Symptoms at Wave 4, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health 2001-2008, Waves l, 3, and 4 (N= 11,727).

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) |

| Identity change (stable identity) | ||||||||||||

| More same-sex oriented | .27 | (.04)*** | .23 | (.04)*** | .22 | (.04)*** | .25 | (.04)*** | .24 | (.04)*** | .25 | (.04)*** |

| Less same-sex oriented | –.03 | (.07) | .01 | (.07) | .01 | (.07) | .03 | (.11) | .03 | (.08) | –.02 | (.09) |

| Sexual orientation identity, Wave 3 (exclusively heterosexual) | ||||||||||||

| Gay/lesbian | .05 | (.11) | .05 | (.11) | .02 | (.13) | .01 | (.13) | .06 | (.13) | .07 | (.16) |

| Bisexual | .11 | (.08) | .02 | (.07) | –.05 | (.09) | –.04 | (.09) | –.02 | (.09) | .09 | (.11) |

| Mostly heterosexual | .16 | (.05)** | .1 1 | (.04)** | .05 | (.05) | .04 | (.03) | .05 | (.06) | .08 | (.06) |

| Female (male) | .14 | (.02)*** | .15 | (.02)*** | .15 | (.02)*** | .15 | (.02)*** | .15 | (.02)*** | .08 | (.02)*** |

| Race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white) | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | .21 | (.03)*** | .17 | (.03)*** | .17 | (.04)*** | .17 | (.03)*** | .17 | (.04)*** | .17 | (.03)*** |

| Hispanic | .03 | (.04) | .02 | (.04) | .02 | (.03) | .02 | (.03) | .02 | (.03) | .01 | (.03) |

| Other race-ethnicity | .06 | (.04) | .06 | (.04) | .07 | (.04) | .07 | (.04) | .07 | (.04) | .05 | (.04) |

| Age, Wave 4 | .01 | (.01) | .01 | (.01) | .01 | (.01) | .01 | (.01) | .01 | (.01) | .01 | (.01) |

| Education level, Wave 4 (college graduate) | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | .53 | (.04)*** | .43 | (.04)*** | .42 | (.04)*** | .42 | (.04)*** | .42 | (.05)*** | .42 | (.05)*** |

| High school graduate | .33 | (.03)*** | .29 | (.04)*** | .28 | (.04)*** | .28 | (.04)*** | .28 | (.04)*** | .29 | (.04)*** |

| Some college | .21 | (.03)*** | .17 | (.03)*** | .16 | (.03)*** | .16 | (.03)*** | .16 | (.03)*** | .16 | (.03)*** |

| Depressive symptoms, Wave 1 | .10 | (.00)*** | .08 | .00*** | .08 | (.00)*** | .08 | (.00)*** | .08 | (.00)*** | .08 | .00*** |

| Psychosocial stressors | ||||||||||||

| Victimization, Wave 3 | .02 | (.05) | .01 | (.06) | .01 | (.05) | .02 | (.06) | .02 | (.06) | ||

| Victimization, Wave 4 | .13 | (.05)* | .13 | (.05)* | .13 | (.05)* | .13 | (.05)* | .13 | (.05)* | ||

| Self-esteem, Wave 3 | .04 | (.01)*** | .04 | (.01)*** | .03 | (.01)*** | .04 | (.01)*** | .04 | (.01)*** | ||

| Self-reported discrimination, Wave 4 | .30 | (.02)*** | .40 | (.02)*** | .40 | (.02)*** | .40 | (.02)*** | .40 | (.02)*** | ||

| Neighborhood-level measures | ||||||||||||

| Percentage Republican (≤ 33%), Wave 3 | ||||||||||||

| > 33% to ≤ 66% | –.03 | (.03) | –.03 | (.03) | –.03 | (.03) | –.03 | (.03) | –.03 | (.03) | ||

| > 66% | –.02 | (.04) | –.02 | (.04) | –.02 | (.04) | –.02 | (.04) | –.02 | (.04) | ||

| Percentage poverty, Wave 3 | .11 | (.11) | .12 | (.10) | .11 | (.10) | .11 | (.10) | .12 | (.10) | ||

| Percentage college degree, Wave 3 | –.10 | (.08) | –.09 | (.08) | –.09 | (.08) | –.09 | (.08) | –.08 | (.08) | ||

| Percentage poverty, Wave 4 | .13 | (.14) | .11 | (.13) | .11 | (.13) | .11 | (.13) | .12 | (.14) | ||

| Percent college degree, Wave 4 | .14 | (.13) | .13 | (.14) | .14 | (.14) | .14 | (.14) | .12 | (.13) | ||

| Percentage some-sex couples (.0%), Wave 3 | ||||||||||||

| Same-sex couples, > 0% to < 2.0% | –.03 | (.02) | –.03 | (.02) | –.03 | (.02) | –.03 | (.02) | –.03 | (.02) | ||

| Same-sex couples, 2.0% to 8.0% | –.02 | (.04) | –.03 | (.04) | –.02 | (.04) | –.03 | (.04) | –.02 | (.04) | ||

| Percentage same-sex couples (0%), Wave 4 | ||||||||||||

| Same-sex couples, > 0% to < 2.0% | .02 | (.02) | .01 | (.03) | .01 | (.04) | .01 | (.02) | .02 | (.02) | ||

| Same-sex couples, 2.0% to 8.0% | .00 | (.04) | .00 | (.04) | .00 | (.02) | .00 | (.04) | .00 | (.04) | ||

| Sexual orientation indicators | ||||||||||||

| Same-sex romantic attraction, Wave 3 (opposite-sex attraction) | .10 | (.05) | .14 | (.05)* | .10 | (.05) | .10 | (.05) | ||||

| Sex before 18 (opposite sex only) | ||||||||||||

| No sex before 18 | –.04 | (.02) | –.03 | (.02) | –.03 | (.02) | –.04 | (.02) | ||||

| Same-sex sex before 18 | .02 | (.05) | .01 | (.05) | .03 | (.05) | .02 | (.05) | ||||

| Romantic relationship (opposite-sex relationship) | ||||||||||||

| No relationship, Wave 3 | .03 | (.04) | .03 | (.04) | .04 | (.04) | .03 | (.04) | ||||

| Same-sex relationship, Wave 3 | –.10 | (.09) | –.09 | (.09) | –.02 | (.10) | –.10 | (.09) | ||||

| Interactions | ||||||||||||

| More Same-sex Oriented × Same-sex Romantic Attraction | –.18 | (.07)* | ||||||||||

| Less Same-sex Oriented × Same-sex Romantic Attraction | –.04 | (.11) | ||||||||||

| More Same-sex Oriented × Same-sex Romantic Relationship | –.34 | (.13)* | ||||||||||

| Less Same-sex Oriented × Same-sex Romantic Relationship | –.21 | (.17) | ||||||||||

| More Same-sex Oriented × Mostly Heterosexual | –.21 | (.10)* | ||||||||||

| More Same-sex Oriented × Bisexual | –.19 | (.20) | ||||||||||

| More Same-sex Oriented × Gay/lesbian | –.57 | (.21)** | ||||||||||

| Less Same-sex Oriented × Mostly Heterosexual | — | |||||||||||

| Less Same-sex Oriented × Bisexual | –.17 | (.18) | ||||||||||

| Less Same-sex Oriented × Gay/lesbian | .17 | (.20) | ||||||||||

| Constant | .06 | (.20) | –.25 | (.22) | –.27 | (.21) | –.27 | (.22) | –.28 | (.22) | –.26 | (.21) |

Note: Referent in parentheses.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001.

Model 1 of Table 1 shows that respondents who shifted toward a more same-sex-oriented identity (β = .27, p < .001) had higher levels of depressive symptoms at Wave 4 compared to persons who reported the same identity over time. Changes in identity toward a less same-sex-oriented identity, however, were not associated with any increase in depressive symptoms. Mostly heterosexual (β = .16, p < .01) respondents in Model 1 reported more depressive symptoms than exclusively heterosexual respondents, but gay/lesbian and bisexual respondents were not more likely to report more depressive symptoms than exclusively heterosexual respondents. Adjusting for psychosocial stressors and the social environment in Model 2 slightly attenuated the relationship between reporting a more same-sex-oriented identity over time (β = .23, p < .001). This trend holds in Model 3, which also adjusts for baseline sexual orientation measures: shifts toward more same-sex-oriented identities are associated with increases in depressive symptoms compared to respondents who reported a stable identity (β = .22, p < .001).

Models 4 through 6 include a series of interactions testing whether the effect of identity change varies by other baseline indicators of sexual orientation. Identity change theory suggests that changes in identity are a stressful process, but ultimately they can improve mental health by reducing cognitive dissonance between external identity and internal evaluations of one's performance of the identity standard. Thus, one would expect that for respondents reporting same-sex romantic attraction or relationships, identity change may improve mental health by reducing cognitive dissonance. And, indeed, the results from Models 4 and 5 show that there is no negative effect of identity change among respondents who report same-sex romantic attraction (.25–.18, p < .05) or relationship (.24–.34, p < .05) at Wave 3. Rather, the negative effect of identity change to a more same-sex-oriented identity is concentrated among respondents who reported opposite-sex-only romantic attraction (β = .25, p < .001) and opposite-sex-only or no relationships at Wave 3 (β = .24, p < .001).

Model 6 interacts identity reported at Wave 3 with identity mobility with baseline reported sexual orientation identity. The results showed that the negative effects of identity change were concentrated among respondents who identified as exclusively heterosexual (β = .25, p < .001) or bisexual at baseline (β = .25–.19, p > .10). For respondents who reported mostly heterosexual identity, identity change was not associated with in an increase in depressive symptoms (β = .25–.21, p < .05), and respondents who reported mostly gay/lesbian identity changes toward more same-sex-oriented identities were associated with decreases in depressive symptoms (β = .25–.57, p < .01). The interactions between identity reported at Wave 3 and changes toward less same-sex-oriented identity were not significant. These results also revealed that sexual minorities who reported stable identities over time do not differ from stable heterosexual-identified respondents.

A series of supplemental analyses that stratified the results by gender and age (Appendix A) revealed that while females were indeed more likely to change sexual orientation identities, for both men and women, changes toward more same-sex-oriented identity were associated positively with depressive symptoms. Similarly, the effect of change on depressive symptoms did not differ between age groups (< 29 years of age compared to ≥ 29 years of age). Additional analyses also assessed the impact of including measures of attraction and relationship reported at Wave 4 of the survey. The inclusion of these measures, however, did not affect the relationship between identity mobility and depressive symptoms. Supplementary analyses were also conducted to assess the impact of geographic relocation on the relationship between identity mobility and depressive symptoms. On average, respondents moved 163 miles between waves, but adjusting for distance moved did not significantly affect the results.

Propensity Score Matching

Previous research has found that transitions toward same-sex-oriented sexuality, in particular, is linked to poorer mental health functioning, a finding that is supported by the results presented in Table 2. Thus, this portion of the analysis focused exclusively on the effect of identity change on depressive symptoms using propensity score analyses. As stated before, multiple matching strategies were used: nearest neighbor, radius, and subclassification. I matched with replacement and specified that the order of matches between the treatment and control units be random.

Table 3 presents the ATE estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the estimates under different matching specifications. ATEs should be interpreted as the direct effect of identity change on the depressive symptoms scale score. ATEs with confidence intervals that cross zero are not statistically significant. The raw effect, which is the mean score of the treatment (identity change) group minus the mean score of the stable group, suggests that respondents who changed their identity between waves reported 1.14 points more on the depressive symptoms scale than those who remained stable in their identity. Once the sample was matched based upon the propensity score, the effect ranged from .49 (95% CI = [.20, .78]) for nearest neighbor matching to 1.13 (95% CI = [.93, 1.33]) for matching using nearest neighbor with a radius specification. These results confirm those presented in Table 2 and show that even when balanced on all covariates, identity change to a more same-sex-oriented identity was associated with increases in depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Average Treatment Effects (ATEs) of Identity Change on Depressive Symptoms, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health 2001-2008, Waves 1, 3, and 4 (N = 11,243).

| Depressive Symptoms |

||

|---|---|---|

| Specification | ATE | 95% CI |

| Raw effect | 1.14 | |

| Nearest neighbor random matching | .49 | [.20, .78] |

| Nearest neighbor radius matching | 1.13 | [.93, 1.33] |

| Stratified matching | .72 | [.51, .93] |

Note: CI = confidence interval.

† p ≤ .10

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001.

Effect of Identity Change by Propensity to Change

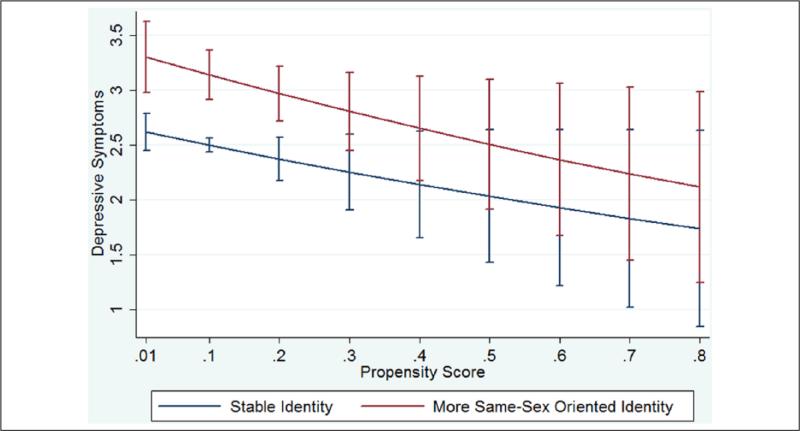

Figure 1 presents the effect of reporting a more same-sex-oriented identity as well as the effect of reporting a stable identity on depressive symptoms by propensity score. Higher scores on the propensity score scale indicate increased probability of reporting an identity change toward a more same-sex-oriented identity. Estimates are derived from fully adjusted negative binomial regression models using the “margins” commands and exclude respondents who reported changes toward less same-sex-oriented identities. The results show that as the propensity score increases, depressive symptoms decrease marginally for both the change and stable groups, but this effect was not statistically significant. The difference in depressive symptoms between respondents reporting a stable identity compared to reporting a same-sex-oriented identity, however, is significant only among respondents with propensity scores below .25, roughly 90% of the sample. After that point, the difference between those who reported change and those who reported stability became nonsignificant. Stated differently, among respondents who have similarly high probabilities of reporting change, those who reported identity change did not report more depressive symptoms than those who did not. These results further confirm the interactions presented in Table 2, which suggested that the negative effects of identity change were concentrated among those who had not previously reported same-sex attraction or romantic relationships.

Figure 1.

Predicted Depressive Symptoms at Wave 4 from Binomial Regression Model, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health 2001–2008, Waves 1, 3, and 4 (N = 11,243).

Note: Predicted values are drawn from fully adjusted negative binomial regression models using the “margins” commands and exclude respondents who reported changes toward less same-sex-oriented identities and account for complex survey design. Results show that significant differences in depressive symptoms between respondents who change identities and those who do not are concentrated among respondents with low propensity to report identity change.

DISCUSSION

This study provides important new insights into the relationship between sexual orientation and mental health during emerging adulthood by examining an understudied mechanism linking sexual minority status and depressive symptoms: sexual identity mobility. This study also provides partial support for traditional models of identity development and identity control theory, which suggest that the period surrounding identity change is a stressful time associated with poorer mental health. The negative effect of identity change on depressive symptoms, however, was observed only among respondents who reported changes toward more same-sex-oriented identities and, more specifically, among those who had not previously reported same-sex attraction, relationships, or a sexual minority identity.

This may be because identity changes toward a more stigmatized identity may trigger anxiety surrounding expected negative reactions from peers and family as well as result in increased exposure to new sources of discrimination and rejection from previous peer and family networks (Corrigan and Matthews 2003; D'Augelli and Grossman 2001; Griffith and Hebl 2002). Exposure to new sources of discrimination, coupled with a lack coping skills for managing discrimination, may be a source of stress that is not experienced by persons that report a less same-sex-oriented identity. While the models controlled for reported victimization and discrimination at Wave 4, these measures most likely do not encompass the variety of minority stress-related experiences that respondents may have experienced as a result of identity change.

Changes in identity toward less same-sex-oriented identities were not associated with increases in depressive symptoms. This may be because while identity change is theorized to be a stressful process, the effect of change may be dependent on the social value of the pre- and post-identity. That is, individuals who report shifts toward heterosexuality may find not just a decrease in the stigma associated with the previous, marginalized identity but also that their new, more opposite-sex-oriented identity comes with additional heteronormative privileges that counterbalance the stress of the process of identity change itself.

This study also examined how the effect of identity change varied by sexual orientation at baseline and the probability of changing identity toward a more same-sex-oriented identity. The relationship between identity change and mental health, therefore, appears to be contingent on the presence of other measures of sexual orientation reported at baseline. This finding is in line with identity control theory and models of sexual orientation identity development, which suggests that in many cases, identity change is done to reduce cognitive dissonance and improve mental health (Burke 2006; Cass 1979; Troiden 1988). Conversely, among respondents who had not previously reported same-sex attraction, romantic relationships, or a heterosexual identity at baseline, identity change was associated with more depressive symptoms in young adulthood. For these respondents, the change to a sexual minority identity may be indicative of lower levels of identity integration, increased initial exposure to homophobia and discrimination, and fewer interactions with other sexual minorities. Any one of these factors may make changing sexual orientation identities a more stressful experience.

It is interesting that the effect of identity change did not vary by whether the respondent reported same-sex behavior before the age of 18 (results not shown). This may be due to the framing of the sexual behavior questions; respondents may have had sexual relationships after the age of 18 but before the reported identity change not captured in this study. The measure of romantic relationships is likely the best proxy for more recent same-sex sexual relationships. More research is needed to understand how identity mobility may be moderated by previous sexual behaviors.

The effect of identity change on depressive symptoms compared to identity stability is also contingent upon the propensity score. Only at lower propensities to change identities is the effect of identity change statistically different from respondents who report a stable identity. Thus, the negative effects of change are no worse than not reporting a change for respondents who are theoretically most likely to report identity change. Those with the highest propensities to change were respondents who reported same-sex-oriented attraction, relationships, and same-sex sex at baseline. Thus, individuals who did not report identity changes but most likely identify as a sexual minority on some dimension (e.g., same-sex attraction, same-sex romantic relationship) may be experiencing some level of cognitive dissonance that, in the short term, cancels out the negative effects of identity change observed among those with lower propensity scores and, in the long term, may result in more depression compared to respondents who change identities to reduce such dissonance. Future research could benefit from observing whether stability in identity post-identity change is associated with subsequent reductions in depressive symptoms.

Another important finding from the results shows that among respondents who reported stable identities over time, there were no differences between gay/lesbian, bisexual, and exclusively heterosexual respondents in depressive symptoms. Other research has found that identity stability in other domains is linked to better health and well-being (Bonanno et al. 2001; Haslam et al. 2008; Iyer and Jetten 2011), and among sexual minorities, sexual orientation identity stability has been linked to higher levels of self-acceptance, identity integration, and self-esteem and better mental health (Floyd and Stein 2002; Needham 2012; Rosario et al. 2006). Recent increases in visibility of alternative sexual identities have facilitated the coming-out process for some youth and young adults; however, sexual minorities who do not identify as such for longer periods of time may avoid doing so because of perceived or real homophobic attitudes of peers and family members (Floyd and Stein 2002). Individuals who identify as sexual minorities at younger ages usually have higher levels of self-esteem than those who delay identification (Jordan and Deluty 1998; Maguen et al. 2002). And until individuals identify with a sexual minority identity, it may be more difficult to access resources and social and romantic networks, which can improve overall self-esteem (Harter 1999) and mental health (La Greca and Harrison 2005). In addition, for marginalized populations, such as sexual minorities, a sexual minority identity may validate in-group norms and serve as a buffer against external sources of stigma and discrimination. The results presented here highlight the importance of the risk period surrounding identity change for contributing to frequently observed disparities in mental health.

There are several limitations to this article. First, this study is unable to examine changes in identity before Wave 3. Respondents who identified with a sexual minority identity may have done so at different ages. Respondents who identified with a sexual minority identity early in life may have done so in part because they live in more supportive or accepting households, whereas many sexual minorities who delayed identification until later in life may have done so to avoid confrontation with their parents or guardians or being kicked out of their homes. Thus, the relationship between identity changes before Wave 3 (which coincides roughly with the time respondents typically would have moved into their own residences) and mental health may be related to the home setting or the social environment rather than the process of identity change itself. This study is also limited in its ability to establish a chronology of certain events, such as same-sex behavior, to create more concrete categories of incongruence between identity and behavior to test whether subsequent identity changes among this subpopulation resulted in better health. I am also unable to determine if victimization and discrimination at Wave 4 occurred before or after the identity change. In addition, there is no detail as to when the identity change may have occurred. Thus, some respondents may have experienced a change in identity in the past several months, whereas others may have experienced the change several years ago. Unfortunately, no other nationally representative longitudinal data set exists with shorter time frames between waves to test these data. Furthermore, the age range of the sample is restricted to the life stage of emerging adulthood. It is unclear whether similar patterns would hold in earlier or later stages of life. Future research could expand upon the results presented here to examine in more detail how depressive symptoms may vary by time since identity change. Unfortunately, I was unable to assess other important indicators of minority stress and other facets of sexual minority identity integration, such as participation in LGBTQ social activities, clubs, politics, internalized homophobia, and identity disclosure, but these may have implications for the relationship between sexual orientation identity change and mental health (Morris 1997; Peterson and Gerrity 2006; Rosario et al. 2001). Finally, due to sample size limitations, the study combined the category of mostly gay/lesbian with exclusively gay/lesbian.

Despite these limitations, this study provides new insights into both identity change theory and the understanding of mental health disparities according to sexual orientation by identifying the process of identity change as an important and understudied source of stress. These results are particularly relevant as younger cohorts experience normative shifts in the process of sexual orientation development, allowing them to explore their sexual orientation for longer periods of time and, as a result, undergo potentially more changes in identity in the life course (Morgan 2013). While these changes have been met with an increasing acceptance of sexual minorities in U.S. society, the results presented here highlight that these changes are not an entirely stress-free process. More research is needed to understand how changing norms around sexual orientation development may affect sexual minority mental health and what factors may alleviate stress associated with the process of identity change.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the three anonymous reviewers as well as Richard Rogers, Stefanie Mollborn, Jason Boardman, Richard Jessor, and Andrew Linke for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or any agencies involved in collecting the data.

FUNDING

The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Grant R03 HD062597, the Office of Research on Women's Health, NICHD Grant K12HD055892, and the University of Colorado Population Center (Grant R24 HD066613) through administrative and computing support. The analysis uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and funded by Grant P01-HD31921 from the NICHD, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. No direct support was received from Grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Biography

Bethany Everett is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and a National Institutes of Health Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health Scholar. Her research focuses on the social determinants of health disparities, in particular, those related to gender and sexual orientation. Currently, she is interested in investigating how stigma and identity development processes interact to shape the physical, mental, and sexual health of sexual-minority men and women.

Appendix

APPENDIX A.

Results from Negative Binomial Regressions Stratified by Gender and Age, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health 2001-2008, Waves 1, 3, and 4 (N = 11,727).

| Depressive Symptoms |

Depressive Symptoms |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women |

Men |

Age <29 |

Age ≥ 29 |

|||||

| β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | |

| Identity change (stable identity) | ||||||||

| More same-sex oriented | .23 | (.04)*** | .17 | (.08)* | .27 | (.05)*** | .12 | (.05)* |

| Less same-sex oriented | –.02 | (.08) | –.01 | (.14) | .01 | (.10) | .02 | (.10) |

| Sexual orientation identity, Wave 3 (exclusively heterosexual) | ||||||||

| Gay/lesbian | .25 | (.20) | –.26 | (.19) | –.10 | (.17) | .03 | (.18) |

| Bisexual | .06 | (.10) | –.34 | (.17)* | –.06 | (.11) | –.02 | (.15) |

| Mostly heterosexual | .10 | (.06) | .01 | (.13) | .13 | (.06)* | –.05 | (.10) |

| Female (male) | .14 | (.03)** | .17 | (.03)** | ||||

| Race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | .14 | (.04)*** | .20 | (.05)*** | .18 | (.04)*** | .15 | (.06)** |

| Hispanic | .05 | (.04) | –.03 | (.05) | .07 | (.04) | –.02 | (.05) |

| Other race-ethnicity | .11 | (.10) | .02 | (.06) | .09 | (.06) | .04 | (.05) |

| Age, Wave 4 | .01 | (.01) | .01 | (.01) | .01 | (.01) | .01 | (.02) |

| Education level, Wave 4 (college graduate) | ||||||||

| Less than high school | .44 | (.07)*** | .41 | (.07)*** | .41 | (.05)*** | .43 | (.07)*** |

| High school graduate | .26 | (.07)*** | .31 | (.06)*** | .33 | (.05)*** | .22 | (.05)*** |

| Some college | .12 | (.04)*** | .21 | (.05)*** | .17 | (.05)*** | .15 | (.04)*** |

| Depressive symptoms, Wave 1 | .07 | (.00)*** | .09 | (.01)*** | .07 | (.00)*** | .09 | (.00)*** |

| Psychosocial stressors | ||||||||

| Victimization, Wave 3 | .13 | (.08) | –.06 | (.07) | .01 | (.07) | .02 | (.10) |

| Victimization, Wave 4 | .02 | (.09) | .18 | (.06)** | .13 | (.06)* | .13 | (.10) |

| Self-esteem, Wave 3 | .04 | (.01)*** | .04 | (.01)** | .03 | (.01)*** | .03 | (.01)*** |

| Self-reported discrimination, Wave 4 | .37 | (.03)*** | .44 | (.04)*** | .40 | (.03)*** | .40 | (.03)*** |

| Community-level measures | ||||||||

| Percentage Republican (≤ 33%), Wave 3 | ||||||||

| >33% to ≤ 66% | –.04 | (.04) | –.01 | (.05) | –.02 | (.04) | –.06 | (.05) |

| > 66% | .02 | (.05) | –.07 | (.05) | –.04 | (.05) | .02 | (.05) |

| Percentage poverty, Wave 3 | .05 | (.12) | .25 | (.14) | .31 | (.12)* | –.20 | (.19) |

| Percentage college degree, Wave 3 | –.06 | (.12) | –.08 | (.11) | –.08 | (.11) | –.14 | (.15) |

| Percentage poverty, Wave 4 | .20 | (.17) | .00 | (.18) | .02 | (.14) | .30 | (.26) |

| Percentage college degree, Wave 4 | –.08 | (.20) | .28 | (.12)* | .11 | (.12) | .11 | (.24) |

| Percent same-sex couples (.0%), Wave 3 | ||||||||

| Same-sex couples, > 0% to < 2.0% | –.01 | (.03) | –.05 | (.04) | –.03 | (.03) | –.01 | (.03) |

| Same-sex couples, 2.0% to 8.0% | –.04 | (.06) | –.01 | (.06) | .01 | (.06) | –.07 | (.06) |

| Percentage same-sex couples (.0%), Wave 4 | ||||||||

| Same-sex couples, > 0% to < 2.0% | .06 | (.03) | –.04 | (.03) | .01 | (.04) | .02 | (.04) |

| Same-sex couples, 2.0% to 8.0% | .01 | (.05) | .00 | (.05) | –.10 | (.05)* | .10 | (.06) |

| Sexual orientation indicators | ||||||||

| Same-sex romantic attraction, Wave 3 (opposite-sex attraction) | .09 | (.06) | .16 | (.09) | .11 | (.06) | .08 | (.07) |

| Sex before 18 (opposite-sex sex only) | ||||||||

| No sex before 18 | –.09 | (.03)** | .01 | (.03) | –.06 | (.03) | –.01 | (.03) |

| Same-sex sex before 18 | –.02 | (.06) | .10 | (.09) | –.03 | (.07) | .14 | (.09) |

| Romantic relationship (opposite-sex relationship) | ||||||||

| No relationship, Wave 3 | .13 | (.05)** | –.06 | (.05) | –.01 | (.05) | .07 | (.06) |

| Same-sex relationship, Wave 3 | –.15 | (.11) | .02 | (.16) | –.13 | (.13) | –.04 | (.12) |

| Constant | .07 | (.27) | –.43 | (.31) | –.17 | (.39) | –.17 | (.62) |

Note: Referent in parentheses.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001.

Footnotes

Supplementary analyses revealed that there were no differences in the effect of identity change by the magnitude of the change. For example, a change from heterosexual to mostly heterosexual would be considered a one-unit change, whereas a change from mostly heterosexual to mostly gay would be a two-unit change. In total, seven indicators were created: one-unit change, two-unit change, and three-unit-or-more change for both directions of change and a single indicator of stability over time. Regressions run with these more detailed categories and post hoc F tests comparing betas revealed that the coefficients were not statistically different. Thus, changes were collapsed into a single indicator to capture any change toward more same-sex-oriented identity and any change toward a less same-sex-oriented identity.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for all Wave 4 tract variables to account for variations in measurement precision. Only 1% of respondents fell out of acceptable margin-of-error range. Analyses that excluded respondents with elevated margins of error and analyses that included a dummy variable for whether respondents had elevated margins of error had no effect on the neighborhood level measures. In order to maximize sample size, these respondents were maintained in the sample.

The data on percentage of Republican voters is not available for Wave 4, and thus, only Wave 3 information on this measure was included in the analyses.

Two percent of the sample reported not being attracted to either men or women; these respondents did not statistically differ from opposite-sex-only-attracted persons and were thus combined.

Add Health also asked about same-sex sexual activity “ever” or “in the past 12 months.” However, in order to ensure correct temporal ordering of behavior and identity change, only sexual relationships reported before the age of 18 were included in the analyses.

All interactions between identity change (changes toward both more and less same-sex identity) and markers of sexual orientation reported at Wave 3 (identity, attraction, relationship, behavior) were tested; however, only significant interactions were included in Table 2.

REFERENCES

- Becker Sascha O., Ichino Andrea. Estimation of Average Treatment Effects Based on Propensity Scores. Stata Journal. 2002;2(4):358–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bell David, Valentine Gill. Queer Country: Rural Lesbian and Gay Lives. Journal of Rural Studies. 1995;11(2):113–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno George A., Papa Anthony, O'Neill Kathleen. Loss and Human Resilience. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2001;10(3):193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Brown George William, Harris Tirril O. Life Events and Illness. Guilford Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J. Identity Change. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2006;69(1):81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J., Reitzes Donald C. The Link between Identity and Role Performance. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1981;44(2):83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Burke Peter J., Stets Jan E. Trust and Commitment through Self-verification. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1999;62(4):347–66. [Google Scholar]

- Burton Chad M., Marshal Michael P., Chisolm Deena J., Sucato Gina S., Friedman Mark S. Sexual Minority-related Victimization as a Mediator of Mental Health Disparities in Sexual Minority Youth: A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42(3):394–402. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9901-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass Vivienne C. Homosexuality Identity Formation: A Theoretical Model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4(3):219–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman Eli. Developmental Stages of the Coming Out Process. Journal of Homosexuality. 1982;7(2/3):31–43. doi: 10.1300/j082v07n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolacion Theodora B., Russell Stephen T., Sue Stanley. Sex, Race/ethnicity, and Romantic Attractions: Multiple Minority Status Adolescents and Mental Health. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):200–14. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan Patrick, Matthews Alicia. Stigma and Disclosure: Implications for Coming Out of the Closet. Journal of Mental Health. 2003;12(3):235–48. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli Anthony R., Grossman Arnold H. Disclosure of Sexual Orientation, Victimization, and Mental Health among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Older Adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16(10):1008–27. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli Anthony R., Pilkington Neil W., Hershberger Scott L. Incidence and Mental Health Impact of Sexual Orientation Victimization of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths in High School. School Psychology Quarterly. 2002;17(2):148–67. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond Lisa M. Sexual Identity, Attractions, and Behavior among Young Sexual-minority Women over a 2-year Period. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(2):241–50. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond Lisa M. Was It a Phase? Young Women's Relinquishment of Lesbian/bisexual Identities over a 5-year Period. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(2):352–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond Lisa M. Female Bisexuality from Adolescence to Adulthood: Results from a 10-year Longitudinal Study. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles Thomas A., Sayegh Aaron M., Dennis Fortenberry J, Zimet Gregory. More Normal Than Not: A Qualitative Assessment of the Developmental Experiences of Gay Male Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(5):425e11–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett Bethany G. Changes in Neighborhood Characteristics and Depression among Sexual Minority Young Adults. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2013;20(1):42–52. doi: 10.1177/1078390313510319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Goldfried Marvin R., Davila Joanne. The Relationship between Experiences of Discrimination and Mental Health among Lesbians and Gay Men: An Examination of Internalized Homonegativity and Rejection Sensitivity as Potential Mechanisms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):917–27. doi: 10.1037/a0029425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]