ABSTRACT

Leukocyte recirculation between blood and lymphoid tissues is required for the generation and maintenance of immune responses against pathogens and is crucially controlled by the L-selectin (CD62L) leukocyte homing receptor. CD62L has adhesion and signaling functions and initiates the capture and rolling on the vascular endothelium of cells entering peripheral lymph nodes. This study reveals that CD62L is strongly downregulated on primary CD4+ T lymphocytes upon infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Reduced cell surface CD62L expression was attributable to the Nef and Vpu viral proteins and not due to increased shedding via matrix metalloproteases. Both Nef and Vpu associated with and sequestered CD62L in perinuclear compartments, thereby impeding CD62L transport to the plasma membrane. In addition, Nef decreased total CD62L protein levels. Importantly, infection with wild-type, but not Nef- and Vpu-deficient, HIV-1 inhibited the capacity of primary CD4+ T lymphocytes to adhere to immobilized fibronectin in response to CD62L ligation. Moreover, HIV-1 infection impaired the signaling pathways and costimulatory signals triggered in primary CD4+ T cells by CD62L ligation. We propose that HIV-1 dysregulates CD62L expression to interfere with the trafficking and activation of infected T cells. Altogether, this novel HIV-1 function could contribute to virus dissemination and evasion of host immune responses.

IMPORTANCE L-selectin (CD62L) is an adhesion molecule that mediates the first steps of leukocyte homing to peripheral lymph nodes, thus crucially controlling the initiation and maintenance of immune responses to pathogens. Here, we report that CD62L is downmodulated on the surfaces of HIV-1-infected T cells through the activities of two viral proteins, Nef and Vpu, that prevent newly synthesized CD62L molecules from reaching the plasma membrane. We provide evidence that CD62L downregulation on HIV-1-infected primary T cells results in impaired adhesion and signaling functions upon CD62L triggering. Removal of cell surface CD62L may predictably keep HIV-1-infected cells away from lymph nodes, the privileged sites of both viral replication and immune response activation, with important consequences, such as systemic viral spread and evasion of host immune surveillance. Altogether, we propose that Nef- and Vpu-mediated subversion of CD62L function could represent a novel determinant of HIV-1 pathogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Effective immune surveillance is dependent on the constitutive recirculation of lymphocytes through anatomically dispersed secondary organs. To gain entry to the peripheral lymph nodes (PLNs), lymphocytes must bind and traverse high endothelial venules (HEVs) through a multistep process that is initiated by the interaction of the lectin-like receptor L-selectin (CD62L) on the surfaces of lymphocytes with glycoproteins expressed by HEVs (e.g., CD34 and GlyCAM-1) (1). CD62L knockout mouse models demonstrated that CD62L plays an essential role in leukocyte homing to lymphoid tissues and sites of inflammation (2), as well as in the generation of T cell responses (3). Engagement of CD62L supports the capture of T lymphocytes from the bloodstream, followed by their rolling along HEVs. Upon binding its ligands, CD62L also initiates a number of events, including activation of signaling cascades, rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton, and enhancement of integrin binding to components of the extracellular matrix expressed by HEVs, which is a prerequisite for T cell arrest and transmigration (4). In addition, CD62L cross talks with the T cell receptor (TCR), since triggering of CD62L provides a costimulatory signal for lymphocyte activation via the TCR (5) and TCR activation enhances the binding activity of CD62L (6). Upon antigen (Ag) stimulation of T cells, the ectodomain of CD62L is cleaved by activated matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) and released in a soluble form (sCD62L), thus allowing reentry into circulation of T cells with helper and effector functions (7). Shedding of CD62L has important physiological consequences and is required for effective viral clearance in a mouse model (8), for chemokine-induced leukocyte migration in in vitro assays (9), and for the acquisition of lytic activity by tumor-reactive T cells (10).

Notwithstanding the important role of CD62L in lymphocyte circulation and function, only a limited number of studies have investigated CD62L in the context of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Wang et al. showed that exposure to HIV-1 alone is sufficient to enhance expression of CD62L on resting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and their CD62L-dependent homing to PLNs upon adoptive transfer in mice, suggesting a link between this phenomenon and development of lymphadenopathy in HIV-1-infected subjects (11). In contrast, various studies have described reduced CD62L expression on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in HIV-1-infected patients (12–14). In addition, HIV-1-infected patients display elevated plasma sCD62L levels (14–16), occasionally above levels that impair leukocyte adhesion to HEVs (17). Whether loss of CD62L+ cells and high sCD62L levels reflect the dysfunction and enhanced activation of the immune system in the infected host or are a direct effect of HIV-1 on CD62L+ cells is not yet clear. Finkel and colleagues reported that ligation of HIV-1 to CD4 and CXCR4 receptors is sufficient to induce MMP-mediated shedding of CD62L on CD4+ T cells (18, 19). Moreover, Marodon et al. showed that CD62L was downmodulated on CD4+ T cells infected in vitro with HIV-1, although the underlying mechanism was not analyzed (20).

In the present study, we investigated the capacity of HIV-1 to modulate cell surface CD62L expression on infected primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. We demonstrate that HIV-1 downmodulates CD62L via the activity of the viral Nef and Vpu proteins, affecting the transport of CD62L molecules to the cell membrane. Furthermore, we show that the CD62L adhesion and signaling functions are impaired in HIV-1-infected primary T cells. Our data suggest that this newly described activity of HIV-1 could be important for viral pathogenesis and AIDS progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Jurkat E6-1 and primary CD4+ T lymphocytes were maintained in complete RPMI 1640 medium, and 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin, all from Euroclone). PBMCs were obtained by Ficoll separation of buffy coats from a donor bank. CD4+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs by negative selection with EasySep Human CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Kit (Stemcell). Prior to adhesion, HIV-infected T cell cultures were depleted of uninfected CD4+ cells using immunomagnetic beads (Dynal; Invitrogen).

Antibodies, reagents, viruses, and expression vectors.

For flow cytometric analysis, the following mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) were used: anti-CD62L-allophycocyanin (APC) (LT-TD180; Thermo Scientific), anti-p24-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (KC57; Beckman Coulter), anti-CD4-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP) (L200; BD Pharmingen), and isotype control IgG1 and IgG2a from EuroBioSciences. As a secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG (GAM) conjugated to Alexa-647 (Invitrogen) was used. For both internalization assays and Western blotting, anti-CD62L Lam1-116 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) MAb was employed.

Additional antibodies employed in Western blotting were as follows: MAbs against green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Clontech), phosphotyrosine (p-Tyr) (PY99; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (MAB374; Millipore) and anti-Nef sheep serum (ARP 444; a kind gift from M. Harris, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom). As secondary reagents, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated GAM (Cell Signaling) and protein G (Bio-Rad) were used.

The DEG56 anti-CD62L and OKT3 anti-CD3 MAbs (eBioscience) and GAM fractionated antiserum (Sigma-Aldrich) were employed in T cell stimulation assays. The anti-human integrin β1 adhesion-blocking MAb (MAB2253; Millipore) was used in adhesion assays.

Where indicated, cells were treated with 25 μM matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor III (MMPI-III) (Calbiochem), 5 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 10 μg ml−1 brefeldin A (BFA), or 100 μg ml−1 cycloheximide (CHX) or with equivalent amounts of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) when used as a solvent (for MMPI), all from Sigma-Aldrich. Other reagents used were phytohemagglutinin (PHA), human plasma fibronectin, Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins B (SEB) and A (SEA) (all from Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 μM atazanavir protease inhibitor (PI) (Reyataz; Bristol-Myers Squibb).

The fusion protein vectors pECFP, pEYFP, pECFP-EYFP, pMEM-EYFP, pNA7Nef-YFP, pVpu-EYFP, pVpuUM2/6-EYFP, and pVpuURD-EYFP have been described previously (21). A plasmid expressing CD62L with a C-terminal cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) tag was constructed by PCR amplification of CD62L from a CemM7 cDNA library using primers 5′-NheI-CCGCTAGCATGATATTTCCATGGAAATG and 3′-AgeI-TCGACCGGTGCACCTGCTCCATATGGGTCATTCATACTTC. Plasmids expressing NL4-3 Nef, SF2 Nef, and NA7 Nef mutants with a C-terminal yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) tag were generated by PCR amplification or splice overlap extension PCR using primers 5′-NheI-CCGGCTAGCATGGGTGGCAAGTGGTC and 3′-AgeI-TCGACCGGTGCACCTGCTCCGCAGTCTTTGTAGTACTC. The ligation procedure has been described previously (21). All PCR-derived inserts were confirmed by sequencing.

Stocks of the X4-tropic HIV-1 NL4-3, either wild-type (wt) virus or virus unable to express Nef (Nef−), Vpu (Vpu−), or both Nef and Vpu (Vpu− Nef−), were prepared by transfecting 20 μg of proviral plasmid and 3.5 μg of pCMV-VSV-G into 293T cells using the calcium phosphate method. For specific experiments (see Fig. 3E), we prepared stocks of wt and mutated NL4-3 viruses in which an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) and the gene encoding enhanced GFP (eGFP) were introduced downstream of the nef coding sequence (NL4-3 nef-IRES-eGFP viruses). The proviral constructs (pBR-NL4-3 and its derivatives) were described previously (22). Stocks of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G (VSV-G)-pseudotyped viruses of the T-tropic SF2 strain (kindly provided by N. Casartelli and O. Schwartz, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) were also prepared. In addition, we used a panel of previously characterized NL4-3-derived viruses carrying mutations in nef that have been described previously (23). NL4-3 wt virus was also prepared in the absence of VSV-G expression, with and without the addition of 1 μM PI to the medium of transfected 293T cells. At 48 h posttransfection, cell culture supernatants were collected, clarified, and stored at −80°C. Viral stocks were titrated by anti-p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Innogenetics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For some experiments, nonpseudotyped NL4-3 virus was inactivated for 1 h at 60°C before use.

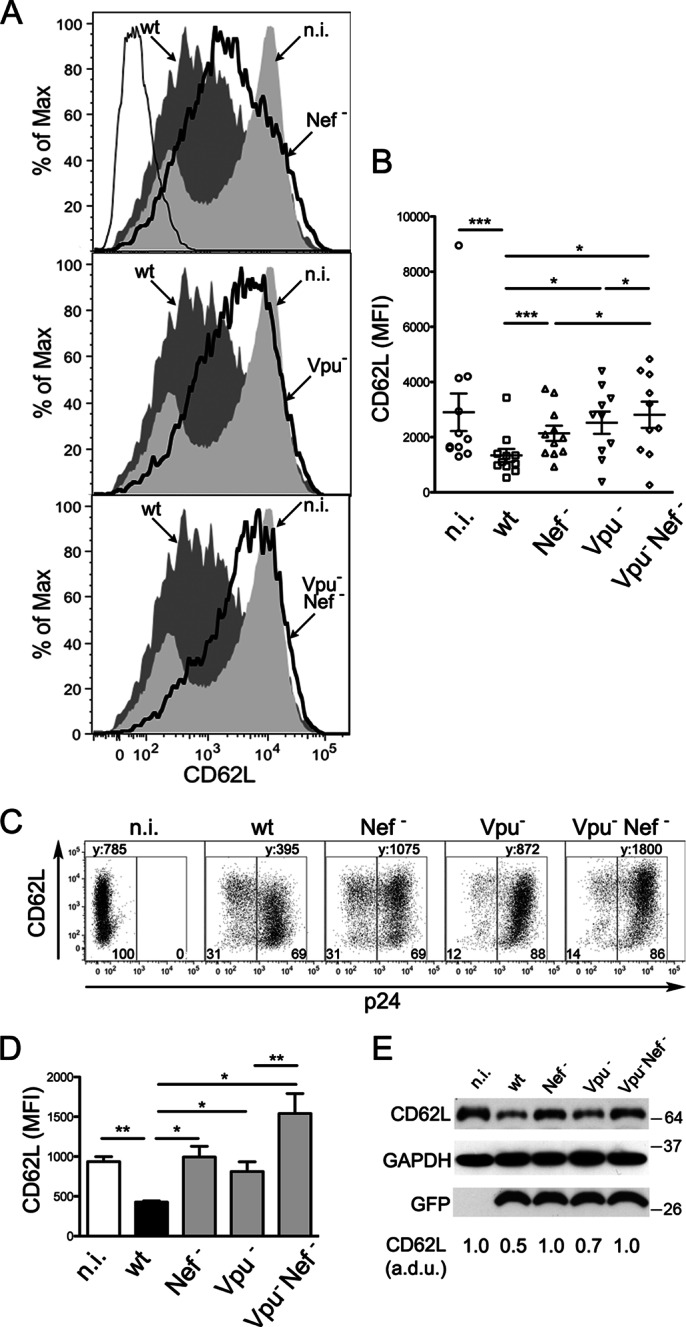

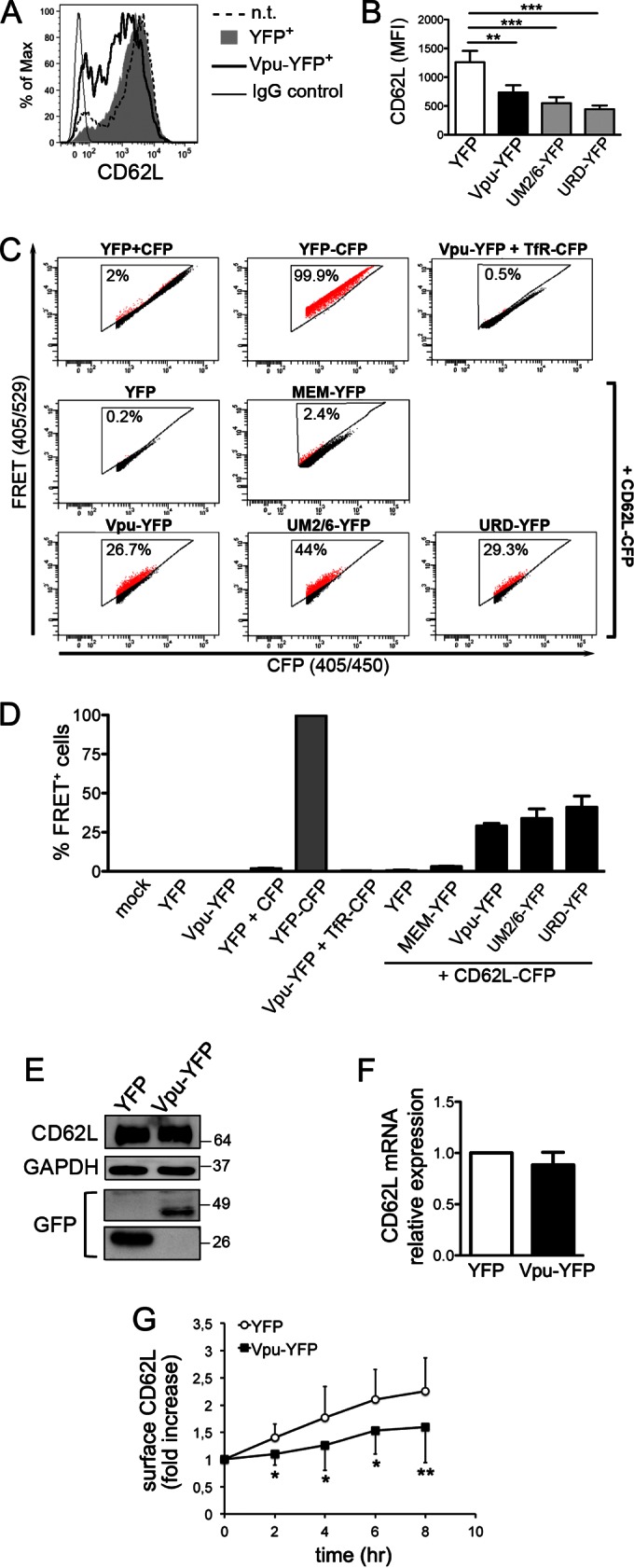

FIG 3.

The HIV-1 Nef and Vpu proteins mediate CD62L downregulation in infected T cells. (A and B) CD4+ T lymphocytes were infected with HIV-1 (wt, Nef−, Vpu−, or Vpu− Nef−) or not infected, activated, and analyzed by flow cytometry as for Fig. 1A. (A) Histograms showing CD62L expression on n.i. cells and on p24pos cells infected with wt or mutated (solid lines) virus; isotype control IgG is also shown (thin line). (B) Scatter dot plot showing mean (±SEM) values for CD62L MFI on T cells from 10 donors; *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (C and D) Jurkat cells were infected with wt or mutated HIV-1 or not infected and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Dot plots showing CD62L expression on n.i. cells (left gate) and on p24pos cells (right gate); CD62L MFI (y) and percentages of gated cells are shown. (D) Means and SEM for CD62L MFI in 5 experiments; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 by t test. (E) Western blotting for CD62L, GFP, and GAPDH on total lysates of Jurkat cells infected with GFP-expressing wt or mutated HIV-1 in one representative experiment out of six; normalized arbitrary densitometric units (a.d.u.) for CD62L and molecular mass standards (kilodaltons) are shown.

HIV-1 infection.

Primary CD4+ T lymphocytes were resuspended at 10 × 107 to 20 × 107 cells ml−1 in medium with 8 μg Polybrene ml−1 either alone or together with 50 ng of p24/106 cells, centrifuged at 2,800 rpm for 30 min at 30°C, and then incubated for 2 h at 37°C with gentle mixing every 30 min. The cells were cultivated at 5 × 106 ml−1 in medium supplemented with 100 IU ml−1 of human recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Sigma-Aldrich). After 5 days, cells were collected and resuspended with fresh medium with irradiated allogeneic PBMCs at a 1:1 cell ratio, with or without 100 ng ml−1 SEB (activated or nonactivated [n.a.] cells), and further cultivated for 3 days before analysis. Alternatively, CD4+ T cells were resuspended in medium containing 100 ng ml−1 SEB and 100 IU ml−1 IL-2 immediately after infection, cultivated for 5 days, and then either analyzed (Fig. 1C) or, for secondary-stimulation experiments, further cultivated in medium, half of which was replaced with fresh medium supplemented with 20 IU ml−1 of IL-2, until they stopped proliferating (day 8). Where indicated (Fig. 1D), 5 × 106 CD4+ T cells were first activated with 1 μg ml−1 PHA and 100 IU ml−1 IL-2 for 3 days and subsequently washed and infected with 500 ng of p24 in a total volume of 2 ml medium. Twelve hours later, the cells were washed to remove the inoculum, and medium containing 5 ml IL-2 (100 IU ml−1) was added. Cells were harvested for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis 7 days later. To infect Jurkat cells, a previously described spin infection method was used (23).

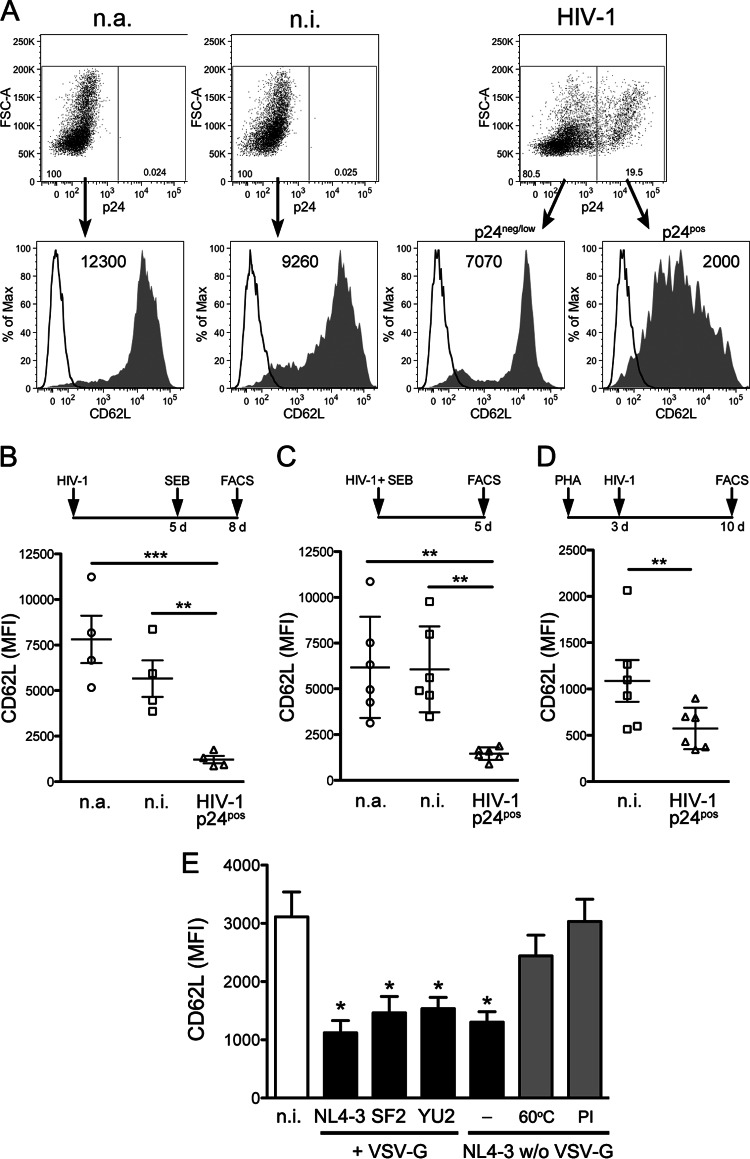

FIG 1.

HIV-1 infection downregulates cell surface CD62L on CD4+ T lymphocytes. (A and B) Primary CD4+ T lymphocytes were infected with HIV-1 (VSV-G-pseudotyped strain NL4-3) or not infected (n.i.), cultivated for 5 days (d), activated with SEB or not activated (n.a.), and analyzed 3 days later by flow cytometry for cell surface CD62L and intracellular HIV-1 p24 expression. (A) The filled histograms show CD62L fluorescence on cells negative for p24 expression or expressing low p24 levels (p24neg/low) and p24pos cells; control IgG (open histograms) and CD62L MFI are also shown. FSC, forward scatter. (B to D) Scatter dot plots depicting mean (±SEM) CD62L MFI from 4 experiments like the one shown in panel A (B), from 6 experiments in which SEB activation was performed immediately after infection and FACS analysis was performed 5 days later (C), and from 6 experiments in which cells were infected 3 days after activation with PHA and analyzed after an additional 7 days (D). (E) CD4+ T cells were infected and analyzed as for panel A with HIV-1 strain NL4-3 or SF2 or HIV-1 NL4-3 that was not pseudotyped, either untreated, heat inactivated (60°C), or treated with PI during virus production. The bars indicate the CD62L MFI (mean and SEM) of noninfected (white and gray) and p24pos (black) cells in 6 experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA.

Transduction with lentiviral vectors and plasmids.

A previously described three-plasmid expression system was used to generate TripNef and TripGFP lentiviruses (kindly provided by P. Charneau) (24). The supernatants containing lentiviruses were harvested 72 h posttransfection and titrated by anti-p24 ELISA. Jurkat cells were transduced with lentiviruses (500 ng p24/106 cells) using the same procedure employed for HIV-1 infection and analyzed after 3 days. Jurkat cells were nucleoporated with 5 μg of plasmid using an Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V (Lonza) and transferred in complete medium for 18 h before analysis. 293T cells were transfected by the standard calcium phosphate method.

Flow cytometry.

The following procedures were performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% NaN3 (staining buffer [SB]). Cells infected with HIV-1 and transduced with lentiviruses and control mock-infected/transduced cells (2 × 105 Jurkat cells, 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 CD4+ T cells, or PBMCs) were incubated for 20 min at 4°C with specific MAbs. For simultaneous detection of intracellular p24, cells were fixed and permeabilized with BD Biosciences reagents and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with anti-p24-FITC MAb. Finally, the cells were washed, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and acquired on a FACSCanto II (or FACSCalibur [see Fig. 5]; BD Biosciences), collecting 104 to 106 cells in the life gate population. Data analyses were performed using FlowJo software. When indicated, transduced Jurkat cells were purified using a FACSAria II cell sorter (more than 95% purity) based on the expression of the YFP marker.

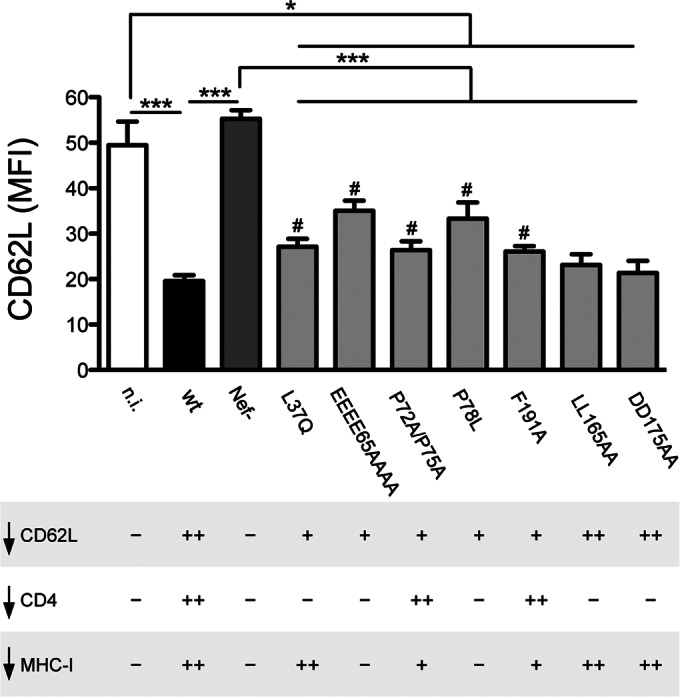

FIG 5.

Phenotype of Nef mutants expressed in the HIV-1 strain NL4-3. Jurkat cells were not infected or were infected with HIV-1 wt, Nef−, or expressing a mutated Nef protein, as indicated, and then analyzed 3 days later for the expression of intracellular p24 and cell surface CD62L, as shown in Fig. 3C. The mutated viruses were described previously (23). The values are means and SEM derived from 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate. The statistically significant differences among samples are indicated (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 by t test), including those between wt-infected cells and cells infected with viruses with Nef mutated (#, P < 0.05 by t test). At the bottom, ++, +, and − indicate full, intermediate, and null downregulation (↓) activity of HIV-1 relative to cell surface CD62L (top), CD4, and MHC-I (described in reference 23).

Inhibition of MMP enzymes.

CD4+ T lymphocytes infected with HIV-1 and activated were harvested 32 h postactivation, resuspended at 4 × 106 cells ml−1 in complete medium supplemented with 25 μM MMPI or equivalent amounts of DMSO solvent, and cultivated for a further 40 h before analysis.

ELISA.

The culture medium of T cells (4 × 106 cells ml−1 cultivated for 40 h) and Jurkat cells (1.5 × 106 cells ml−1 cultivated for 18 h), diluted 1:20 and 1:10, respectively, in sample diluent buffer, was used to quantify sCD62L using the Human L-Selectin ELISA kit (Boster Biological Technology).

Western blotting.

Jurkat cells and CD4+ T lymphocytes were lysed as described previously (25); then, 20 μg of total cell lysates was separated on SDS-10% PAGE and immunoblotted with primary and secondary antibodies. To detect CD62L, nonreducing conditions (without β-mercaptoethanol) were used. The protein-specific signals were detected with Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Scientific) and quantified by densitometry.

RT-PCR.

In Jurkat cells expressing HIV-1 Nef or Vpu-YFP protein (or irrelevant GFP and YFP control proteins), the amounts of CD62L mRNA normalized by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) mRNA were measured by standard semiquantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). Briefly, total RNA was extracted, using TRIzol (Life Technologies), from Jurkat cells at 24 h and 72 h postransduction with YFP/Vpu-YFP plasmids and TripGFP/TripNef lentiviruses, respectively. Aliquots (2 μg) of total RNA extracted by the transduced Jurkat cells were used to generate cDNA using random hexamers and reagents from Bioline, and increasing amounts of cDNA were amplified by PCR using reagents from GE Healthcare. For each target, forward (F) and reverse (R) primers were designed across exons to avoid amplification of genomic DNA, as validated in pilot assays: CD62L(F), 5′-CAGCCCTCTGTTACACAGCTT-3′; CD62L(R), 5′-GCCCATAGTACCCCACATCA-3′; G6PDH(F), 5′-ATCGACCACTACCTGGGCAA-3′; and G6PDH(R), 5′-TTCTGCATCACGTCCCGGA-3′. The number of cycles (30) was set to the exponential phase of the PCR in order to allow semiquantitative comparisons among samples.

Flow cytometry-based internalization and transport assays.

To measure the rate of CD62L internalization, 48 h after transduction with TripNef and TripGFP lentiviruses, Jurkat cells were washed with cold PBS, reacted with anti-CD62L Lam1-116 MAb (2 μg ml PBS−1) for 30 min on ice, washed twice, and placed at 37°C and 5% CO2 for the indicated time in RPMI containing 25 μM MMPI. Although dispensable (data not shown), MMPI was added to avoid any potential shedding of antibody-bound CD62L molecules during the incubation period. The endocytosis reaction was stopped by transferring cells on ice and adding NaN3 at a final 0.4% concentration. Next, the cells were washed, stained with Alexa 647-GAM, washed again using SB, and resuspended in 1% PFA prior to flow cytometric analysis. For the CD62L transport assay, Jurkat cells transduced with TripNef/TripGFP lentivirus and nucleoporated with pEYFP/pVpu-YFP vector were harvested 48 h and 24 h postransduction, respectively. To remove cell surface CD62L, the cells were incubated with 5 ng ml−1 PMA in RPMI for 30 min at 37°C and 5% CO2 and then washed and resuspended in complete RPMI supplemented with 25 μM MMPI and placed for the indicated time at 37°C and 5% CO2, with the exception of an aliquot of cells that was removed and placed on ice. Then, the cells were stained with anti-CD62L-APC antibody, fixed with 1% PFA, and analyzed by flow cytometry. In addition, to calculate the amount of CD62L transported at the plasma membrane as a percentage of total CD62L protein, cells were stained first and then permeabilized (cell surface CD62L staining), as well as first permeabilized and then stained (intracellular CD62L staining), and the following formula was used: [cell surface MFI/(cell surface MFI + intracellular MFI)] × 100, where MFI is the geometric mean fluorescence intensity. The values obtained at each time point were subtracted from that obtained at time zero. In pilot tests, the CD62L MFI values obtained by the sum of independent cell surface and intracellular staining coincided with the values obtained by performing the two procedures sequentially.

FACS-FRET.

Flow cytometric measurement of Förster resonance energy transfer (FACS-FRET) was performed as described previously (21). Importantly, the method allows the measurement of protein interactions in living cells, and independently and multiple times, we confirmed FRET-measured interactions by biochemical assays and in virus-infected cells, demonstrating that FACS-FRET is a robust assay to assess protein interactions (21, 26, 27). Briefly, 150,000 293T cells were seeded in a 12-well plate and transfected 12 h later. Cells were harvested 24 h posttransfection and assayed for FACS-FRET analysis with a FACSCanto II (BD Bioscience). As an additional negative control, we introduced measurement of MEM-YFP, which is highly palmitoylated, versus CD62L-CFP. Since MEM-YFP is strongly expressed, we titrated the construct for transfection versus Na7 Nef-YFP to achieve similar YFP expression levels. CFP and FRET were measured by exciting cells with a 405-nm laser, and CFP emission was collected with a standard 450/40 filter, while FRET was measured with a 529/24 filter (Semrock). YFP was excited with a 488-nm laser, and emission was collected with a 529/24 filter (Semrock). At least 10,000 CFP/YFP-positive cells were analyzed for FRET. The exact hierarchical-gating strategy we used for FACS-FRET has been described previously (21).

T cell stimulation and proliferation assays.

Primary CD4+ T lymphocytes infected and activated with SEB and SEA 8 days earlier were collected, washed once with PBS, resuspended at 18 × 106 cells ml−1 either with cold PBS alone and maintained on ice (time zero) or with cold PBS supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 of anti-CD62L DREG56 antibody and incubated at 37°C for various times (1, 5, and 10 min). The incubations were stopped by rapid washing with cold PBS, and then, the T cells were lysed for Western blotting. To measure T cell proliferation in response to secondary stimulation, CD4+ T cells at day 8 postinfection/activation were counted, centrifuged, and adjusted to a final concentration of 4 × 106 cells ml−1 using conditioned culture medium diluted 1:1 with fresh complete medium without IL-2. Next, CD4+ T cell cultures were supplemented with GAM (1:90 dilution of fractionated antiserum), restimulated by adding anti-CD3 antibody (5 μg ml−1) or both anti-CD3 and anti-CD62L (10 μg ml−1) antibodies or not stimulated, and cultivated for 3 days. The EdU thymidine analogue (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine; Invitrogen) was added (10 μM) to cultures 24 h before cell harvesting. To detect EdU incorporated into infected and noninfected (n.i.) cells, the manufacturer's recommendations for the Click-iT EdU Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Invitrogen) were followed. After the Click-iT reaction, the cells were washed, reacted with anti-p24-FITC MAb, and then washed again using the kit component E buffer for all steps. Finally, the cells were resuspended in 1% PFA and analyzed by flow cytometry.

T cell adhesion assay.

At day 7 postinfection/activation, purified (CD4−) HIV-1-infected T lymphocytes and control CD4+ noninfected T cells were tested for their capacity to adhere to plastic-immobilized fibronectin following a previously described method with some modifications (28). Flat-bottom 96-well enzyme immunoassay (EIA)/ radioimmunoassay (RIA) plates (Costar) were treated or not overnight at 4°C with 100 μl/well of a 20-μg ml−1 solution of human fibronectin in PBS. Next, both coated and uncoated wells were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 100 μl/well of PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2 (the same buffer was used in all subsequent steps). The T cells were resuspended at 1.33 × 106 cells ml−1, supplemented with anti-CD62L antibody (DREG56; 10 μg/ml) or equal amounts of mouse IgG1 and GAM (1:90), and then added in triplicate to fibronectin-coated and uncoated wells (75 μl/well; 105 cells/well), and the plate was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. For blocking experiments, anti-β1 MAB2253 MAb was added (20 μg ml−1) during the 37°C incubation. Unbound cells were removed and pooled with two subsequent 100-μl washes, centrifuged, resuspended in 1% PFA, and counted. Bound cells were detached by incubating with 75 μl of 5 mM EDTA in PBS for 5 min at 37°C and pipetting several times and then counted after the addition of 25 μl 4% PFA. Dead cells were excluded by standard Trypan blue staining. For each well, the percentage of adherent cells was calculated using the following formula: 100 × (number of cells that remained bound after washing/total number of bound and unbound cells). The data are expressed as the percentage of cells adherent to plastic-immobilized fibronectin minus the percentage of cells adherent to uncoated plastic.

Confocal microscopy.

To analyze CD62L distribution, 293T cells were fixed 24 h posttransfection for 20 min at 4°C with 2% PFA. Coverslips were mounted onto slides using Mowiol and imaged by spinning-disc confocal microscopy using an inverted Nikon TiE microscope equipped with the UltraVIewVoX System (PerkinElmer). Images were generated at ×100 magnification. YFP was excited with a 514-nm laser and CFP with a 440-nm laser.

Statistical analysis.

The Graph Pad Prism Version 5.0 software package was used to evaluate statistical significance by applying one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student's t test.

RESULTS

HIV-1 infection induces CD62L downregulation in CD4+ T lymphocytes.

To investigate the effect of HIV-1 infection on CD62L, human primary CD4+ T lymphocytes were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 (strain NL4-3) or not infected, cultivated for 5 days prior to antigenic stimulation, and analyzed 3 days later by flow cytometry to measure the expression of cell surface CD62L and intracellular p24 Gag capsid antigen. Due to T cell activation, CD62L levels were somewhat lower on n.i. cells than on n.a. cells (Fig. 1A). Importantly, CD62L was downmodulated by ∼80% on infected p24-positive (p24pos) T cells than on n.i. cells (P = 0.0008) (Fig. 1A and B). Similar CD62L downmodulation on infected p24pos T cells was also observed if antigenic stimulation was performed immediately after HIV-1 infection (Fig. 1C) or if the cells were activated with PHA 3 days before infection (Fig. 1D).

The downregulation of CD62L was not a unique property of NL4-3, since reduced CD62L levels were also found on CD4+ T cells infected with SF2, an HIV-1 strain closely resembling primary isolates (Fig. 1E).

A prior study suggested that contact with HIV-1 by itself, even in the absence of viral entry and replication, lowers cell surface CD62L levels (18). To test this hypothesis, CD4+ T cells were exposed to NL4-3 stocks devoid of VSV-G and inactivated either by heat (60°C) or by the presence of PI (i. e., atazanavir) during virus assembly. The control untreated NL4-3 virus was as capable as its VSV-G-pseudotyped counterpart of downmodulating CD62L (Fig. 1E). On the other hand, CD4+ T cells exposed to inactivated virus were not infected and maintained normal CD62L levels (Fig. 1E), indicating that productive infection, not simply virus exposure, induced CD62L downmodulation. Altogether, HIV-1 infection of primary CD4+ T cells causes the robust downmodulation of CD62L from the cell surface.

Downmodulation of CD62L by HIV-1 is not due to enhanced proteolytic shedding.

CD62L downmodulation on HIV-1-infected T cells could be due to increased protein shedding by MMPs, a family of enzymes activated during HIV-1 infection through poorly understood mechanisms (29). To address this point, we measured by ELISA the amounts of sCD62L accumulating in the medium of primary CD4+ T lymphocytes infected or not with HIV-1 and cultivated with a broad-spectrum MMPI (25 μM) or equivalent amounts of DMSO solvent, a procedure that we previously set up (30). In control cultures (DMSO), noninfected and HIV-infected cells released amounts of sCD62L that were comparable and ∼2-fold higher than that of nonactivated cells, indicating that CD62L shedding induced by T cell activation occurs independently of HIV-1 (Fig. 2, top). In addition, MMPI completely inhibited activation-driven CD62L release in both uninfected and infected cell cultures, bringing sCD62L down to levels similar to those of nonactivated cells. Moreover, MMPI significantly reduced CD62L downregulation on HIV-1-infected cells but failed to completely restore CD62L expression to levels found on MMPI-treated uninfected cells, as measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 2, bottom). Taken together these data indicate that HIV-1 reduces CD62L on infected T cells via a mechanism distinct from proteolytic shedding.

FIG 2.

CD62L is shed by activated CD4+ T lymphocytes with and without HIV-1 infection. CD4+ T cells infected or not with HIV-1, as described in the legend to Fig. 1A, were treated with MMPI-III (25 μM) or with solvent (DMSO), and the levels of CD62L in the cell medium (top) and on the cell surface (bottom) were analyzed by ELISA and flow cytometry, respectively. Means and SEM from 6 experiments are shown. *, P < 0.05 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

The HIV-1 Nef and Vpu proteins mediate CD62L downregulation in infected T cells.

HIV-1 encodes two accessory factors, Nef and Vpu, both with the capacity to interfere with the cell surface expression of membrane proteins, with important consequences for viral pathogenesis and spread in vivo (31). To investigate whether Nef and Vpu play a role in the reduction of CD62L, primary CD4+ T lymphocytes were infected with HIV-1, either wt or defective for the expression of Nef, Vpu, or both proteins (Nef−, Vpu−, and Vpu− Nef−, respectively), and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The expression of CD62L on CD4+ T cells infected with wt HIV-1 (MFI ± standard error of the mean [SEM], 1,340 ± 235) was lower than for n.i. cells (2,900 ± 680) but did not change significantly when n.i. cells were compared to cells infected with Nef−, Vpu−, and Vpu− Nef− viruses (2,140 ± 275, 2,525 ± 405, and 2,810 ± 475, respectively) (Fig. 3A and B). In addition, infection with Vpu− Nef− virus resulted in higher CD62L levels than infection with Nef− or Vpu− virus. These data indicate that the downregulation of CD62L in HIV-1-infected T cells is mediated by both Nef and Vpu. The two viral proteins can independently affect CD62L, but they likely synergize, given that the mean downregulation activity of wt virus (∼55% in a set of 10 experiments) exceeded the sum of the activities of Nef− and Vpu− viruses (∼26% and 13%, respectively).

The phenotype of wt and mutated viruses in relation to CD62L downregulation was maintained in the Jurkat E6.1 cell line (Fig. 3C and D), a CD4+ CD62L+ T lymphoblastoma line that can be infected by HIV-1 up to 90%. Jurkat cells were also infected with a set of viruses expressing GFP and analyzed by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 3E, the CD62L protein levels were reduced in cells infected with wt HIV-1 compared to noninfected cells (up to 50% reduction; P = 0.002 by t test). Lower levels of total CD62L protein were also observed in cells infected with Vpu− virus, but not in cells infected with Nef− or Vpu− Nef− virus, suggesting that Nef, but not Vpu, is capable of reducing CD62L steady-state expression levels.

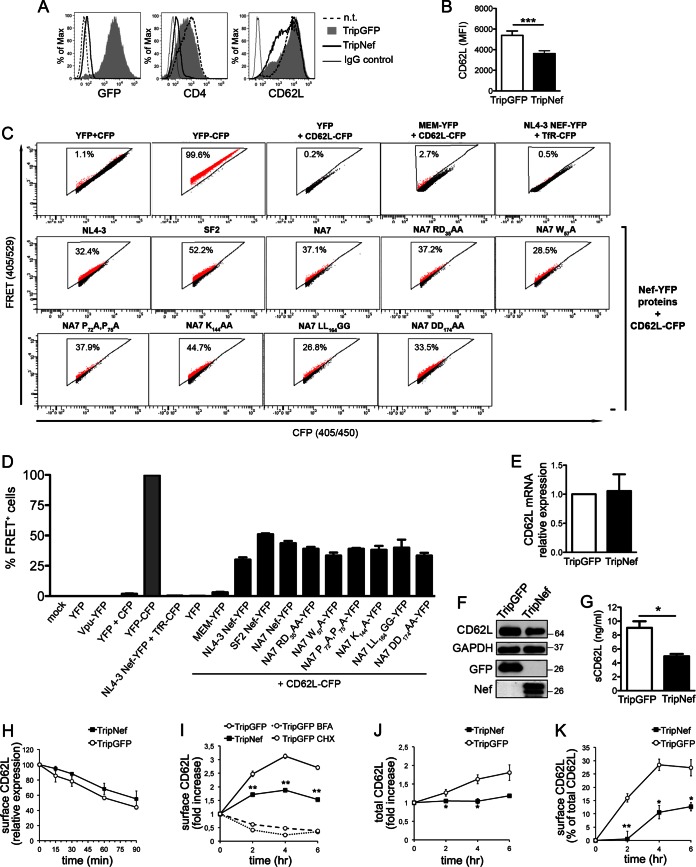

HIV-1 Nef downmodulates CD62L by reducing the protein steady-state level and transport to the cell membrane.

To study the role of Nef in the regulation of CD62L, the NL4-3 Nef protein or GFP as a control was expressed in Jurkat cells by means of the Trip lentivirus transduction system (24). After 72 h, cells transduced with TripNef lentivirus lost cell surface CD4 expression (an indicator for the presence of Nef) and displayed reduced CD62L levels compared to control GFP+ cells (3,615 ± 275 versus 5,389 ± 431 [MFI ± SEM]), while the levels of another surface molecule, CD3, were maintained (Fig. 4A and B and data not shown). Thus, the Nef protein has the capacity to downmodulate CD62L when expressed out of the context of HIV-1 infection. We then used a flow cytometry-based FRET assay previously established in our laboratory (21) to analyze Nef-CD62L interaction. By measuring cells coexpressing CFP and YFP versus expression of a CFP-YFP fusion protein, real FRET signals can be discriminated from the background with high confidence (e.g., the primary FACS plots in Fig. 4C). Therefore, FRET+ cells shift into the triangular FRET gate (Fig. 4C, population colored red; the percentages of cells shifting into the FRET gate are shown). As shown in the representative FACS plots in Fig. 4C and the quantitative analysis in Fig. 4D, the coexpression in 293T cells of the C-terminally tagged fusion proteins NL4-3 Nef-YFP and CD62L-CFP resulted in the appearance of 32.0% ± 0.8% (mean ± standard deviation [SD]; n = 3) FRET+ cells, while irrelevant background signals were obtained with all negative controls (individual or combined expression of YFP and CFP or coexpression of CD62L-CFP with an unrelated YFP-tagged protein, MEM-YFP, or of Nef-YFP with the transmembrane transferrin protein tagged with CFP, TfR-CFP), strongly indicating that Nef interacts with CD62L in living cells. In addition, binding to CD62L was detected using YFP-tagged Nef proteins of the SF2 and NA7 HIV-1 strains (51.0% ± 1.3% and 43.6% ± 4.1%, respectively). Different Nef variants mutated at conserved motifs that are important for binding to CD4 (i.e., RD35, W57, LL164, and DD174) or SH3 domains (P72P75) maintained the capacity to bind CD62L in the FRET-based assay (Fig. 4C and D); thus, distinct yet-undiscovered residues in Nef mediate interaction with CD62L. Next, we used Jurkat cells transduced with Trip lentiviruses to investigate the mechanisms by which Nef mediates CD62L downmodulation. First, similar CD62L mRNA levels were found in Nef- and GFP-expressing cells (Fig. 4E). On the other hand, Nef-expressing cells displayed reduced overall CD62L protein content and released smaller sCD62L amounts than GFP+ control cells, as measured by immunoblotting and ELISA, respectively (Fig. 4F and G), implying that Nef enhances degradation and/or impairs new synthesis of CD62L. Then, based on the well-known capacity of Nef to disrupt the intracellular trafficking of molecules such as CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) (32), we investigated the kinetics of CD62L internalization and transport to the cell membrane with and without Nef. By means of a FACS-based endocytosis assay, we found similar rates of CD62L internalization in Jurkat cells transduced with TripNef and TripGFP lentiviruses (Fig. 4H). To measure the anterograde transport of CD62L, we exploited the effect of PMA phorbol ester to induce rapid CD62L shedding from the cell membrane and a rise in CD62L mRNA levels (33). Jurkat cells were treated for 30 min with 5 ng/ml PMA, resulting in 80 to 90% reduction of cell surface CD62L, and then, the cells were washed, cultivated in the presence of MMPI-III to impede any further shedding, and tested over time for the reappearance of CD62L on the cell membrane. This assay closely measures the transport of newly synthesized CD62L molecules, since both inhibition of protein synthesis with CHX and impairment of protein sorting from the Golgi apparatus with BFA can block cell surface CD62L reemergence (Fig. 4I). As depicted in Fig. 4I, CD62L appearance on the cell membrane was reduced up to 50% in Nef-expressing cells compared with control GFP+ cells. During the CD62L transport assay, the total amounts of synthesized CD62L protein (calculated by cell surface plus intracellular staining) did not increase significantly in Nef-expressing cells as opposed to control cells (Fig. 4J), consistent with Nef's capacity to induce degradation and/or to impair new synthesis of CD62L. However, by calculating the amount of CD62L emerging at the cell surface as a percentage of total CD62L, this was strongly reduced if Nef was expressed (Fig. 4K); therefore, impairment of CD62L transport to the plasma membrane was due to a specific Nef activity, not to the overall decrease of CD62L protein in Nef-expressing cells. Taken together, these results suggest that Nef downregulates CD62L by reducing steady-state protein levels and by interfering with CD62L anterograde transport. At present, the amino acid residues in Nef that are required for the CD62L downregulation activity have not been identified, despite the fact that several Nef proteins mutated at conserved residues were tested in the context of cells infected with HIV-1 (Fig. 5) or expressing individual Nef variants (data not shown). Of note, Nef mutations that inhibit the protein's capacity to downregulate CD4 (L37Q, LL165AA, and DD175AA), MHC-I (EEEE65AAAA, P72A/P75A, and F191A), or both target molecules (P78L) either retained full CD62L downregulation activity (LL165AA and DD175AA) or were only partially impaired compared to wt Nef (Fig. 5). Therefore, to interfere with CD62L expression, Nef likely uses residues that differ from those required for CD4 and MHC-I downregulation.

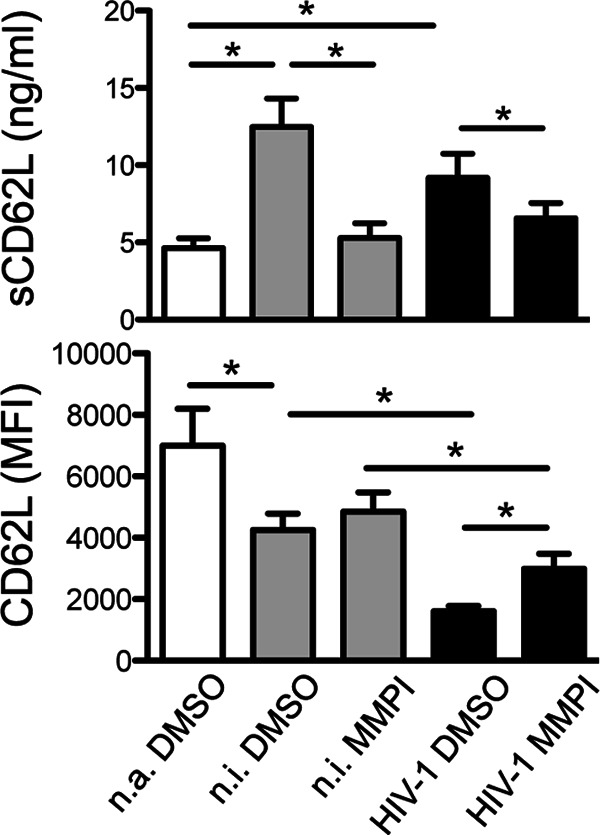

FIG 4.

Nef downmodulates CD62L by reducing protein steady-state levels and transport to the cell membrane. (A, B, and E to K) Jurkat T cells were transduced with TripGFP or TripNef lentivirus or not transduced (n.t.) and analyzed 72 h later. (A) Histograms showing the fluorescence distributions of GFP, CD4, and CD62L on n.t. and TripGFP- and TripNef-transduced cells; relative control IgG is also shown. (B) Means and SEM of CD62L MFI in 15 experiments. (C and D) FACS-FRET analysis of Nef-CD62L interaction in 293T cells expressing the indicated CFP and YFP fusion proteins. A representative experiment (C) and mean percentages and SD of FRET+ cells (red) from 3 experiments (D) are shown. Mock, mock transfected. (E) In TripGFP- and TripNef-transduced Jurkat cells, the amounts of CD62L mRNA normalized by G6PDH mRNA were measured. The mean (and SEM) relative amounts of CD62L mRNA in Nef-expressing cells compared with control cells from 3 experiments are shown. (F) Western blotting for CD62L, GAPDH, GFP, and Nef on total lysates of Jurkat cells transduced as for panel A in one out of three experiments. Molecular mass standards are indicated (kilodaltons). (G) Mean (and SEM) levels of sCD62L in the medium of TripGFP- and TripNef-transduced Jurkat cells measured by ELISA in 3 experiments. (H) CD62L internalization in TripGFP- and TripNef-transduced Jurkat cells; mean (and SEM) values of CD62L expression calculated over time with respect to initial expression (set to 100%) in 3 experiments. (I to K) Transport of newly synthesized CD62L to the cell membrane in TripGFP- and TripNef-transduced Jurkat cells measured over time and expressed as fold increase over time zero (set to 1) (I) or as a percentage of total CD62L protein (cell surface plus intracellular) over time zero (set to 0) (K). Total CD62L protein amounts expressed as fold increase over time zero (set to 1) (J) and results obtained with TripGFP-transduced cells in the presence of BFA or CHX (I) are also shown. The data are expressed as means (±SEM) from 3 experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 by t test.

The anterograde transport of newly synthesized CD62L molecules is reduced by Vpu.

In order to investigate the effect of Vpu on CD62L expression, Jurkat cells were transfected with a plasmid coding for the NL4-3 Vpu protein tagged at the C terminus with the yellow fluorescent protein (Vpu-YFP) or encoding YFP alone and analyzed 18 h later by flow cytometry to measure CD62L on YFP+ cells. The expression of Vpu-YFP resulted in an ∼42% decrease of cell surface CD62L compared to cells transfected with YFP or not transfected (Fig. 6A). Two well-characterized YFP-tagged mutated variants of Vpu were also tested: UM2/6-YFP, in which alanine substitution for S52 and S56 residues abrogated the capacity of Vpu to degrade both CD4 and tetherin, and URD-YFP, which cannot target tetherin due to the presence of a randomized transmembrane (TM) domain (21). Figure 6B shows that both mutants maintained the CD62L downregulation activity of the wild-type protein, indicating that Vpu uses residues distinct from S52 and S56 and the TM domain to target CD62L. FACS-FRET analysis of 293T cells expressing CD62L-CFP together with Vpu-YFP, UM2/6-YFP, or URD-YFP revealed 29.1% ± 4.9%, 33.9% ± 10.4%, and 41.1% ± 15.9% FRET+ cells (mean ± SD; n ≥ 3), respectively (Fig. 6C and D). These data indicate that Vpu binds to CD62L and that this association is not mediated by the S52 and S56 residues or the TM region of Vpu. Moreover, Vpu-YFP+ and YFP+ Jurkat cells were purified by FACS-based cell sorting and used to prepare total protein extract and RNA for immunoblotting or RT-PCR analysis of CD62L expression, respectively. The steady-state CD62L protein content was not significantly affected by the presence of Vpu (Fig. 6E), indicating that, as opposed to CD4 and tetherin, CD62L was not redirected to degradation by Vpu. Besides, since CD62L mRNA levels were not affected upon Vpu expression (Fig. 6F), CD62L downregulation by Vpu could not be ascribed to impaired transcription, unlike another Vpu target, interferon regulatory factor 3 (34). A well-established property of Vpu relies on its capacity to interfere with the anterograde transport of cellular targets, such as CD4 and tetherin (35); therefore, Vpu-YFP- and YFP-expressing Jurkat cells were used to perform a CD62L transport assay. The results show that, similarly to Nef, Vpu inhibits the transport of newly synthesized CD62L molecules toward the cell surface (Fig. 6G).

FIG 6.

Cell surface CD62L expression and transport of newly synthesized CD62L molecules are reduced by Vpu. Jurkat cells were transfected with plasmid expressing YFP or Vpu-YFP or not transduced. (A) Histograms showing cell surface CD62L expression of n.t. cells and of gated YFP+ cells transduced with YFP (filled gray histogram) or Vpu-YFP (solid line); n.t. cells stained with control IgG are also shown. (B) Means and SEM of CD62L MFI on transfected Jurkat cells expressing YFP or YFP-tagged Vpu proteins, either wt (Vpu-YFP) or mutated (UM2/6-YFP and URD-YFP), in 5 experiments. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA. (C and D) Analysis of Vpu-CD62L interaction by FACS-FRET in 293T cells expressing the indicated CFP and YFP fusion proteins. A representative experiment (C) and mean percentages (and SD) of FRET+ cells from at least 3 experiments (D) are shown. (E) Western blotting for CD62L, GAPDH, and YFP of total lysates of Jurkat cells transduced with YFP or Vpu-YFP and sorted by FACS in one out of three experiments. Molecular mass standards are indicated (kilodaltons). (F) Relative CD62L mRNA expression in Vpu-YFP-transduced Jurkat cells compared with control YFP-transduced cells, shown as means and SEM from 3 experiments. (G) The transport of newly synthesized CD62L to the cell membrane was analyzed as for Fig. 4I, and data are expressed as means (±SEM) from 3 experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 by t test.

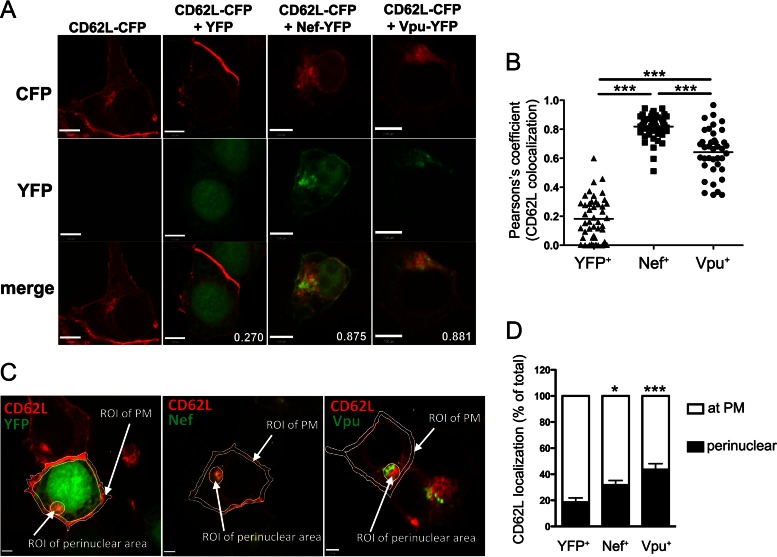

Nef and Vpu induce CD62L relocalization in perinuclear compartments.

To investigate the intracellular distribution of CD62L upon Nef and Vpu expression, we analyzed transfected 293T cells expressing CD62L-CFP, together with Nef-YFP or Vpu-YFP, by confocal microscopy. In control cells transfected with CD62L-CFP alone or together with YFP, the CD62L-CFP protein was detected mainly at the plasma membrane (PM) and, to a lesser extent, at internal membranes (Fig. 7A). The YFP-tagged viral proteins displayed their normal distribution, with Nef localized primarily at the PM but also in perinuclear compartments, such as the trans-Golgi network (TGN), while Vpu was distributed mainly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), TGN, and other perinuclear membranes and, to a lesser extent, at the PM (Fig. 7A). In cotransfected cells, we observed strong colocalization of CD62L-CFP with both Nef-YFP and Vpu-YFP (Fig. 7A and B), further supporting the capacity of the viral proteins to associate with CD62L observed in the FACS-FRET measurements. Most importantly, we found that, upon coexpression of either Nef-YFP or Vpu-YFP, the localization of CD62L-CFP at the PM was reduced and a larger fraction of CD62L-CFP resided in perinuclear compartments (Fig. 7C and D). Altogether, these results suggest that both Nef and Vpu associate with and sequester CD62L in perinuclear compartments.

FIG 7.

Nef and Vpu sequester CD62L in perinuclear compartments. 293T cells transiently expressing CD62L-CFP alone or together with YFP, Nef-YFP, or Vpu-YFP were analyzed by spinning-disc confocal microscopy. (A) Representative micrographs of individual channels corresponding to CFP (red), YFP (green), and merged CFP/YFP images, with values corresponding to Pearson's coefficients of CD62L colocalization with YFP and YFP-tagged proteins. Bars, 7 μm. (B) Pearson's coefficients of CD62L overlapping with YFP or YFP-tagged proteins in cells transfected as indicated (n = 40 cells per condition); means are also shown. ***, P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA. (C and D) The CD62L fluorescence signal was measured in the regions of interest (ROI): the PM and perinuclear area. (D) Mean percentages of CD62L at the PM and in the perinuclear area calculated by setting at 100% the sum of PM and perinuclear signals (n = 10 cells per condition); the error bars represent SEM. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 by unpaired t test.

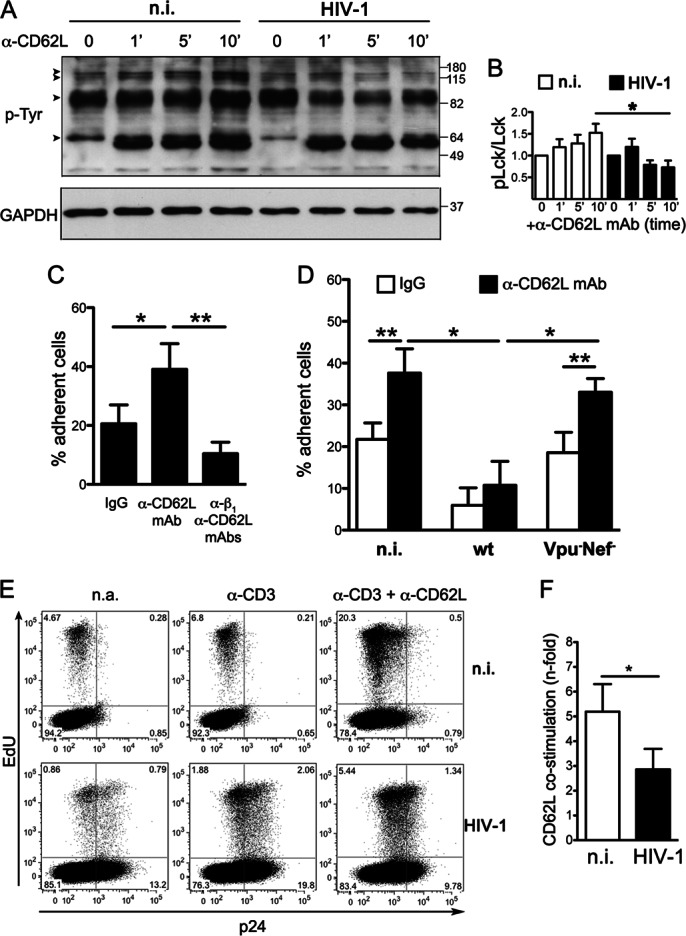

T cell activation and adhesion via CD62L are impaired by HIV-1.

Finally, we investigated the functional consequences of reduced CD62L expression on the surfaces of HIV-1-infected T cells. First, we analyzed the capacity of HIV-1-infected T cells to respond to CD62L triggering in terms of protein phosphorylation. Specifically, primary CD4+ T lymphocytes were infected or not with HIV-1, activated, and cultured for 8 days until they reacquired a resting phenotype (data not shown). Then, the cells were stimulated with anti-CD62L DREG56 MAb for various times before immunoblotting analysis with an anti-p-Tyr antibody. In accordance with a previous study (36), CD62L stimulation induced progressive accumulation of various phosphoproteins. However, some of these phosphoproteins clearly increased to a lesser extent in HIV-1-infected T cells than in n.i. cells (Fig. 8A). In particular, at 10 min after CD62L triggering, the phosphorylation efficiency of the Lck src-tyrosine kinase was significantly lower in cells infected with HIV-1 (Fig. 8B).

FIG 8.

T cell activation and adhesion to fibronectin via CD62L are impaired by HIV-1. (A and B) Resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes infected or not with HIV-1 were restimulated with anti-CD62L MAb (DREG56) for the indicated times (minutes) and analyzed by Western blotting total cell lysates for p-Tyr and GAPDH. One representative experiment out of three is shown. (A) The arrowheads indicate phosphoproteins accumulating to a lesser extent in HIV-1-infected cells; molecular mass standards are indicated (kilodaltons). (B) Quantitative comparison of Lck phosphorylation was performed as described in Materials and Methods; the data are expressed as means and SEM. (C and D) Binding to immobilized fibronectin of T cells infected with wt or Vpu− Nef− HIV-1 (both depleted of CD4+ cells) or not infected in the presence of either anti-CD62L MAb or mouse IgG1. (C) Only n.i. cells were employed, and anti-β1 blocking antibody was also added, together with DREG56. Means and SEM from two (C) or three (D) experiments in triplicate are shown. (E and F) Cellular proliferation measured as percentages of EdU+ cells in HIV-infected or noninfected resting CD4+ T cells restimulated or not with cross-linked anti-CD3 antibody alone or in combination with anti-CD62L MAb; the numbers depict percentages of gated cells. Shown are one representative experiment (E) and data from 4 experiments expressed as the mean (and SEM) percent EdU+ CD3/CD62L-stimulated cells divided by percent EdU+ CD3-stimulated cells (F). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 by t test.

Next, we employed a previously established adhesion assay in which ligation of CD62L with antibodies stimulates the capacity of T cells to bind immobilized fibronectin (28). In pilot experiments, we observed that anti-CD62L DREG56 MAb increased adhesion of CD4+ T lymphocytes by ∼2-fold and that this response was mediated by β1 integrin, because it was inhibited by anti-β1 blocking antibody (Fig. 8C). Since loss of cell surface CD4 is a hallmark of HIV-1 infection, primary resting T cells infected with wt or Vpu− Nef− HIV-1 were purified by immunodepleting CD4+ T cells and then tested in the adhesion assay, together with parallel cultures of n.i. cells with and without anti-CD62L MAb. Of note, adherence of HIV-1-infected T cells was not stimulated by CD62L ligation, with the percentage of cells bound to fibronectin significantly lower than that of CD62L-stimulated n.i. cells (11% ± 6% versus 38% ± 6%; P = 0.047) (Fig. 8D). The impaired response is in line with the reduced expression and function of CD62L, not with the levels of β1 integrin that were expressed to normal levels in HIV-1-infected T cells (data not shown). In addition, CD62L ligation of T cells infected with Vpu− Nef− virus that maintained normal cell surface CD62L levels induced an increase in binding similar to that observed in n.i. cells and higher than that of T cells infected with wt HIV-1 (33% ± 3% versus 11% ± 6% adherent cells with Vpu− Nef− and wt virus, respectively; P = 0.039) (Fig. 8D). Therefore, HIV-1 inhibits T cell adhesion in response to CD62L engagement via Nef and Vpu.

Next, we tested whether CD62L downmodulation was also associated with a reduced capacity of infected T cells to proliferate in response to simultaneous CD3 and CD62L stimulation. Specifically, resting HIV-1-infected and n.i. T cells were cultivated with or without cross-linked antibodies (anti-CD3 alone or together with anti-CD62L MAb) for 3 days. Then, cellular proliferation was evaluated by measuring by flow cytometry the incorporation of the EdU thymidine analogue. Figure 8E shows that CD62L costimulation resulted in an increase in the percentage of Edu+ cells compared to CD3 stimulation alone in both n.i. and HIV-1-infected cells. However, the costimulatory effect of CD62L on infected cells was inferior to that observed with n.i. cells (2.9- ± 0.8- versus 5.2- ± 1.1-fold Edu+ cell increase over CD3 stimulation alone) (Fig. 8E and F). Overall, these data indicate that the CD62L downmodulation induced by HIV-1 results in impaired cellular activation, adhesion, and proliferation of infected T cells in response to CD62L ligation.

DISCUSSION

The present study reveals that expression of the CD62L homing receptor is strongly downregulated by the viral Nef and Vpu proteins in HIV-1-infected T cells, a phenomenon that profoundly affects the migratory potential of virus-carrying cells.

In HIV-1-infected T cells, Nef reduces the cell surface expression of several proteins, including virus receptors (e.g., CD4 and CXCR4), antigen-presenting molecules (e.g., MHC-I), costimulatory molecules (e.g., CD28), and ligands for immune-activating receptors (e.g., PVR, MIC, and ULBP proteins) (23, 31, 37), thus favoring at various levels the production of infectious progeny virions and evasion of host immune responses. Based on the work of several laboratories, Nef is regarded as a versatile molecular adaptor that misdirects cellular proteins away from the plasma membrane by recruiting endosomal coat proteins, such as the adaptor protein complex (AP-1 and AP-2). As a consequence of the formation of a ternary complex with Nef and coat proteins, target molecules are rapidly internalized from the plasma membrane (e.g., CD4) or retained within intracellular compartments (e.g., MHC-I) and partially rerouted to late endosomes and lysosomes for degradation (32). In the present study, we found that Nef does not affect the rate of CD62L internalization but rather impedes the transport of newly synthesized CD62L molecules to the plasma membrane via CD62L sequestration in TGN/ER compartments. In addition, total CD62L levels were reduced in Nef-expressing cells, in accordance with Nef redirecting CD62L to protein degradation pathways. Since inhibitors of lysosomes or proteasomes affected constitutive CD62L expression (data not shown), we could not use them to test the contributions of these compartments to CD62L reduction by Nef. Furthermore, the fact that none of several Nef mutants with impaired downmodulation of CD4 and/or MHC-I lost the capacity to bind CD62L and impede its cell surface expression (Fig. 4C and D and 5), suggests that Nef uses a distinct, not yet identified mechanism to target CD62L.

Synergistically with Nef, the Vpu protein downmodulated CD62L. HIV-1 Vpu was reported to downmodulate CD4, tetherin (also called BST-2 or CD317), the NK-T and B cell antigen (NTB-A), and PVR (23, 38). In general terms, Vpu does not interfere with protein endocytosis but is provided with the capacity to bind and sequester target proteins in intracellular compartments during their anterograde trafficking to the cell membrane. In line with this, we showed that Vpu impairs the transport of newly synthesized CD62L molecules to the plasma membrane and induces accumulation of CD62L in perinuclear compartments. We also found that, unlike CD4 and tetherin but similarly to NTB-A and PVR, CD62L is targeted by Vpu without being degraded and independently of intact S52 and S56 Vpu residues. Interestingly, a unique feature of CD62L downmodulation is that the Vpu TM domain is not required, as opposed to other downmodulation activities of Vpu. Therefore, our results on CD62L downregulation increase the functional complexity of Vpu, which is capable of modifying the trafficking of several cellular proteins through mechanisms that share common elements yet are distinct.

It is becoming increasingly clear that, by using Nef and Vpu jointly, HIV-1 has evolved a complex, multifaceted strategy to ensure the removal of CD4 and other membrane proteins. Indeed, very recent work from our laboratory and another indicates that HIV-1 Nef and Vpu share the capacity to downmodulate various cell surface molecules besides those previously reported and CD62L (reference 39 and our unpublished data). The efficiency of such a strategy may reside in the fact that the Nef and Vpu proteins are expressed with different timing during HIV-1 infection (early versus late, respectively), display some differences in intracellular distribution (mainly at the PM versus the ER, respectively), and interact with distinct components of the protein-trafficking and degradation machineries (as discussed above). In general, the functional convergence of two viral proteins using distinct mechanisms to target the same molecule implies that elimination of such a target must play an important role in the virus life cycle. It is thus logical to infer that HIV-1 must have evolved the capacity to downmodulate CD62L via Nef and Vpu to promote its propagation.

To assess the biological relevance of reduced CD62L expression, we tested CD62L-mediated signaling and adhesion interactions of HIV-1-infected primary T cells. First, we found that HIV-1 limited the accumulation of various phosphoproteins, including the src-tyrosine kinase Lck, in response to CD62L ligation with a specific antibody. Normally, capping of CD62L with ligand or antibody elicits a number of signaling cascades, mostly dependent on Lck, such as activation of Ras and the mitogen-activating protein kinase (MAPK), synthesis of reactive oxygen compounds, and Rac-mediated rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton (4, 40). One key event triggered by CD62L ligation is activation of β1 and β2 integrins that, by interacting with their Ig superfamily ligands, mediate the transition from fast to slow rolling of leukocytes along HEVs (28, 41). Accordingly, we demonstrated that CD4+ T cells infected with wt virus, but not Vpu− Nef− virus, were strongly impaired in binding the β1 ligand fibronectin upon CD62L ligation compared to noninfected cells. Furthermore, in line with reduced CD62L signaling, we found that the costimulatory effect of CD62L on TCR-activated HIV-1-infected cells was significantly inferior to that observed with noninfected cells in terms of cellular proliferation.

The consequences of the HIV-1 ability to inhibit CD62L expression and function could be highly relevant in vivo. First, the loss of CD62L on CD4+ T lymphocytes infected within lymphoid tissues, which are the major site of ongoing viral replication, will predictably allow the egress of virus-producing T cells from lymphoid tissues into efferent lymph vessels, thus favoring their circulation and systemic HIV-1 infection. Indeed, by means of intravital microscopy in humanized mice, Murooka and colleagues demonstrated that blocking the egress of HIV-1-infected human T cells from PLNs with a drug inhibited virus dissemination and strongly reduced plasma viremia (42). Therefore, the CD62L downregulation activity evolved by HIV-1 arms the virus with a strong spreading potential. On the other hand, circulating CD4+ T cells that become infected outside lymphoid tissues are impaired in their capacity to migrate to the PLNs as a consequence of CD62L downregulation. Since PLNs are the major site of immune response induction, reduced entry into PLNs of HIV-1-infected T cells most likely decreases the initiation of anti-HIV immune responses. Interestingly, Stolp et al. showed that the individual expression of the HIV-1 Nef protein interferes with trafficking of murine CD4+ T lymphocytes in vivo, specifically impairing their homing to lymph nodes at the transmigration step from the HEV into the lymph node parenchyma (43). The authors suggested that Nef-mediated constraint of murine T cell homing to lymph nodes relies, in large part, on the inhibition of actin remodeling via the F195 Nef residue, but also on additional mechanisms potentially involving reduced expression of CD62L and the CCR7 chemokine receptor. Other studies performed with Nef-expressing Jurkat cells showed that Nef inhibits cell adhesion to fibronectin or endothelial cells and slows down cell migration toward chemokines, but CD62L expression was not investigated (44, 45). In addition, very recently, it was shown that Vpu downmodulates CCR7 on the surfaces of CD4+ T cells (46) and that HIV-1 infection of resting IL-7-treated CD4+ T cells results in reduced expression of CD62L and, to a lesser extent, CCR7 (47). The present study adds novel information by underscoring the capacity of Nef and Vpu to downmodulate the CD62L homing receptor, a phenomenon that should profoundly affect trafficking of HIV-1-infected T cells in vivo. Finally, as we showed that HIV-1-infected T cells respond poorly to CD62L ligation in terms of signaling-cascade activation and cellular proliferation, it is conceivable that CD62L downregulation may help productively infected cells to avoid activation-induced cell death or even to revert to a resting state and become latently infected, hence favoring viral persistence.

The capacity of HIV-1 to downmodulate CD62L implies that CD62L+ CD4+ T lymphocytes could be progressively depleted in chronically HIV-1-infected patients, as, indeed, we observed in a pilot study (our unpublished data) and as reported by Hengel and colleagues (48, 49). However, reduction of circulating CD4+ CD62L+ T cells may be caused in the infected host by dysfunctional T cell proliferation, differentiation, and homing or by chronic immune activation. Moreover, studies on resting CD4+ T cells exposed in vitro to HIV-1 reported transient downmodulation (18, 19) or, conversely, upmodulation of CD62L (11). Therefore, the influence of HIV-1 on CD62L expression on bystander T cells clearly awaits elucidation. The continuous progress of in vivo cell-tracking techniques and humanized-mouse models will likely offer future opportunities to study CD62L-regulated T cell dynamics in HIV-1 infection and how they may influence anti-HIV-1 immune responses and viral propagation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata to M.D. and L.V. and Ricerca Corrente, cofunded by the Italian 5 × 1,000, to M.D.) and by grants from the German Research Council (DFG) (SCHI1073/2-1 and SCHI1073/4-1) and the Else Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung (2012_A264) to M.S.

We thank P. Charneau, N. Casartelli, O. Schwartz, and M. Harris for providing reagents and E. Giorda for cell sorting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khan AI, Kubes P. 2003. L-selectin: an emerging player in chemokine function. Microcirculation 10:351–358. doi: 10.1080/mic.10.3-4.351.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbones ML, Ord DC, Ley K, Ratech H, Maynard-Curry C, Otten G, Capon DJ, Tedder TF. 1994. Lymphocyte homing and leukocyte rolling and migration are impaired in L-selectin-deficient mice. Immunity 1:247–260. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu J, Grewal IS, Geba GP, Flavell RA. 1996. Impaired primary T cell responses in L-selectin-deficient mice. J Exp Med 183:589–598. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wedepohl S, Beceren-Braun F, Riese S, Buscher K, Enders S, Bernhard G, Kilian K, Blanchard V, Dernedde J, Tauber R. 2012. L-selectin: a dynamic regulator of leukocyte migration. Eur J Cell Biol 91:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murakawa Y, Minami Y, Strober W, James SP. 1992. Association of human lymph node homing receptor (Leu 8) with the TCR/CD3 complex. J Immunol 148:1771–1776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spertini O, Kansas GS, Munro JM, Griffin JD, Tedder TF. 1991. Regulation of leukocyte migration by activation of the leukocyte adhesion molecule-1 (LAM-1) selectin. Nature 349:691–694. doi: 10.1038/349691a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galkina E, Tanousis K, Preece G, Tolaini M, Kioussis D, Florey O, Haskard DO, Tedder TF, Ager A. 2003. L-selectin shedding does not regulate constitutive T cell trafficking but controls the migration pathways of antigen-activated T lymphocytes. J Exp Med 198:1323–1335. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards H, Longhi MP, Wright K, Gallimore A, Ager A. 2008. CD62L (L-selectin) down-regulation does not affect memory T cell distribution but failure to shed compromises anti-viral immunity. J Immunol 180:198–206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan AI, Landis RC, Malhotra R. 2003. L-selectin ligands in lymphoid tissues and models of inflammation. Inflammation 27:265–280. doi: 10.1023/A:1026056525755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang S, Liu F, Wang QJ, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA. 2011. The shedding of CD62L (L-selectin) regulates the acquisition of lytic activity in human tumor reactive T lymphocytes. PLoS One 6:e22560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Robb CW, Cloyd MW. 1997. HIV induces homing of resting T lymphocytes to lymph nodes. Virology 228:141–152. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SW, Royal W III, Semba RD, Wiegand GW, Griffin DE. 1998. Expression of adhesion molecules and CD28 on T lymphocytes during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 5:583–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes PJ, Miao YM, Gotch FM, Gazzard BG. 1999. Alterations in blood leucocyte adhesion molecule profiles in HIV-1 infection. Clin Exp Immunol 117:331–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meddows-Taylor S, Kuhn L, Meyers TM, Tiemessen CT. 2001. Altered expression of L-selectin (CD62L) on polymorphonuclear neutrophils of children vertically infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Clin Immunol 21:286–292. doi: 10.1023/A:1010935409997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spertini O, Schleiffenbaum B, White-Owen C, Ruiz P Jr, Tedder TF. 1992. ELISA for quantitation of L-selectin shed from leukocytes in vivo. J Immunol Methods 156:115–123. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90017-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kourtis AP, Nesheim SR, Thea D, Ibegbu C, Nahmias AJ, Lee FK. 2000. Correlation of virus load and soluble L-selectin, a marker of immune activation, in pediatric HIV-1 infection. AIDS 14:2429–2436. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200011100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu L, Poe JC, Kadono T, Venturi GM, Bullard DC, Tedder TF, Steeber DA. 2002. A functional role for circulating mouse L-selectin in regulating leukocyte/endothelial cell interactions in vivo. J Immunol 169:2034–2043. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marschner S, Freiberg BA, Kupfer A, Hunig T, Finkel TH. 1999. Ligation of the CD4 receptor induces activation-independent down-regulation of L-selectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:9763–9768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Marschner S, Finkel TH. 2004. CXCR4 engagement is required for HIV-1-induced L-selectin shedding. Blood 103:1218–1221. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marodon G, Landau NR, Posnett DN. 1999. Altered expression of CD4, CD54, CD62L, and CCR5 in primary lymphocytes productively infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 15:161–171. doi: 10.1089/088922299311583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banning C, Votteler J, Hoffmann D, Koppensteiner H, Warmer M, Reimer R, Kirchhoff F, Schubert U, Hauber J, Schindler M. 2010. A flow cytometry-based FRET assay to identify and analyse protein-protein interactions in living cells. PLoS One 5:e9344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schindler M, Münch J, Kirchhoff FF. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibits DNA damage-triggered apoptosis by a Nef-independent mechanism. J Virol 79:5489–5498. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5489-5498.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matusali G, Potesta M, Santoni A, Cerboni C, Doria M. 2012. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef and Vpu proteins downregulate the natural killer cell-activating ligand PVR. J Virol 86:4496–4504. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05788-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mordelet E, Kissa K, Cressant A, Gray F, Ozden S, Vidal C, Charneau P, Granon S. 2004. Histopathological and cognitive defects induced by Nef in the brain. FASEB J 18:1851–1861. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2308com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neri F, Giolo G, Potesta M, Petrini S, Doria M. 2011. The HIV-1 Nef protein has a dual role in T cell receptor signaling in infected CD4+ T lymphocytes. Virology 410:316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagen N, Bayer K, Rösch K, Schindler M. 2014. The intraviral protein interaction network of hepatitis C virus. Mol Cell Proteomics 13:1676–1689. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.036301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, Zhang K, Stadler D, Cheng X, Sprinzl MF, Koppensteiner H, Makowska Z, Volz T, Remouchamps C, Chou WM, Thasler WE, Hüser N, Durantel D, Liang TJ, Münk C, Heim MH, Browning JL, Dejardin E, Dandri M, Schindler M, Heikenwalder M, Protzer U. 2014. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science 343:1221–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1243462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giblin PA, Hwang ST, Katsumoto TR, Rosen SD. 1997. Ligation of L-selectin on T lymphocytes activates beta1 integrins and promotes adhesion to fibronectin. J Immunol 159:3498–3507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mastroianni CM, Liuzzi GM. 2007. Matrix metalloproteinase dysregulation in HIV infection: implications for therapeutic strategies. Trends Mol Med 13:449–459. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matusali G, Tchidjou HK, Pontrelli G, Bernardi S, D'Ettorre G, Vullo V, Buonomini AR, Andreoni M, Santoni A, Cerboni C, Doria M. 2013. Soluble ligands for the NKG2D receptor are released during HIV-1 infection and impair NKG2D expression and cytotoxicity of NK cells. FASEB J 27:2440–2450. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-223057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchhoff F. 2010. Immune evasion and counteraction of restriction factors by HIV-1 and other primate lentiviruses. Cell Host Microbe 8:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roeth JF, Collins KL. 2006. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef: adapting to intracellular trafficking pathways. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70:548–563. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00042-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaldjian EP, Stoolman LM. 1995. Regulation of L-selectin mRNA in Jurkat cells. Opposing influences of calcium- and protein kinase C-dependent signaling pathways. J Immunol 154:4351–4362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotter D, Kirchhoff F, Sauter D. 2013. HIV-1 Vpu does not degrade interferon regulatory factor 3. J Virol 87:7160–7165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00526-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dubé M, Bego MG, Paquay C, Cohen EA. 2010. Modulation of HIV-1-host interaction: role of the Vpu accessory protein. Retrovirology 7:114. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brenner B, Gulbins E, Schlottmann K, Koppenhoefer U, Busch GL, Walzog B, Steinhausen M, Coggeshall KM, Linderkamp O, Lang F. 1996. L-selectin activates the Ras pathway via the tyrosine kinase p56lck. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:15376–15381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cerboni C, Neri F, Casartelli N, Zingoni A, Cosman D, Rossi P, Santoni A, Doria M. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Nef protein downmodulates the ligands of the activating receptor NKG2D and inhibits natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Gen Virol 88:242–250. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokarev A, Guatelli J. 2011. Misdirection of membrane trafficking by HIV-1 Vpu and Nef: keys to viral virulence and persistence. Cell Logist 1:90–102. doi: 10.4161/cl.1.3.16708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haller C, Müller B, Fritz JV, Lamas-Murua M, Stolp B, Pujol F, Keppler OT, Fackler OT. 1 October 2014. HIV-1 Nef and Vpu are functionally redundant broad-spectrum modulators of cell surface receptors including tetraspanins. J Virol doi: 10.1128/JVI.02333-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ivetic A. 2013. Signals regulating L-selectin-dependent leucocyte adhesion and transmigration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hwang ST, Singer MS, Giblin PA, Yednock TA, Bacon KB, Simon SI, Rosen SD. 1996. GlyCAM-1, a physiologic ligand for L-selectin, activates beta 2 integrins on naive peripheral lymphocytes. J Exp Med 184:1343–1348. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murooka TT, Deruaz M, Marangoni F, Vrbanac VD, Seung E, von Andrian UH, Tager AM, Luster AD, Mempel TR. 2012. HIV-infected T cells are migratory vehicles for viral dissemination. Nature 490:283–287. doi: 10.1038/nature11398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stolp B, Imle A, Coelho FM, Hons M, Gorina R, Lyck R, Stein JV, Fackler OT. 2012. HIV-1 Nef interferes with T-lymphocyte circulation through confined environments in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:18541–18546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204322109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nobile C, Rudnicka D, Hasan M, Aulner N, Porrot F, Machu C, Renaud O, Prevost MC, Hivroz C, Schwartz O, Sol-Foulon N. 2010. HIV-1 Nef inhibits ruffles, induces filopodia, and modulates migration of infected lymphocytes. J Virol 84:2282–2293. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02230-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park IW, He JJ. 2009. HIV-1 Nef-mediated inhibition of T cell migration and its molecular determinants. J Leukoc Biol 86:1171–1178. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0409261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramirez PW, Famiglietti M, Sowrirajan B, DePaula-Silva AB, Rodesch C, Barker E, Bosque A, Planelles V. 2014. Downmodulation of CCR7 by HIV-1 Vpu results in impaired migration and chemotactic signaling within CD4(+) T cells. Cell Rep 7:2019–2030. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trinité B, Chan CN, Lee CS, Mahajan S, Luo Y, Muesing MA, Folkvord JM, Pham M, Connick E, Levy DN. 2014. Suppression of Foxo1 activity and down-modulation of CD62L (L-selectin) in HIV-1 infected resting CD4 T cells. PLoS One 9:e110719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hengel RL, Jones BM, Kennedy MS, Hubbard MR, McDougal JS. 1999. Markers of lymphocyte homing distinguish CD4 T cell subsets that turn over in response to HIV-1 infection in humans. J Immunol 163:3539–3548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hengel RL, Jones BM, Kennedy MS, Hubbard MR, McDougal JS. 2001. CD4+ T cells programmed to traffic to lymph nodes account for increases in numbers of CD4+ T cells up to 1 year after the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Infect Dis 184:93–97. doi: 10.1086/320997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]