ABSTRACT

Glycoprotein D (gD) plays an essential role in cell entry of many simplexviruses. B virus (Macacine herpesvirus 1) is closely related to herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and encodes gD, which shares more than 70% amino acid similarity with HSV-1 gD. Previously, we have demonstrated that B virus gD polyclonal antibodies were unable to neutralize B virus infectivity on epithelial cell lines, suggesting gD is not required for B virus entry into these cells. In the present study, we confirmed this finding by producing a B virus mutant, BV-ΔgDZ, in which the gD gene was replaced with a lacZ expression cassette. Recombinant plaques were selected on complementing VD60 cells expressing HSV-1 gD. Virions lacking gD were produced in Vero cells infected with BV-ΔgDZ. In contrast to HSV-1, B virus lacking gD was able to infect and form plaques on noncomplementing cell lines, including Vero, HEp-2, LLC-MK2, primary human and macaque dermal fibroblasts, and U373 human glioblastoma cells. The gD-negative BV-ΔgDZ also failed to enter entry-resistant murine B78H1 cells bearing a single gD receptor, human nectin-1, but gained the ability to enter when phenotypically supplemented with HSV-1 gD. Cell attachment and penetration rates, as well as the replication characteristics of BV-ΔgDZ in Vero cells, were almost identical to those of wild-type (wt) B virus. These observations indicate that B virus can utilize gD-independent cell entry and transmission mechanisms, in addition to generally used gD-dependent mechanisms.

IMPORTANCE B virus is the only known simplexvirus that causes zoonotic infection, resulting in approximately 80% mortality in untreated humans or in lifelong persistence with the constant threat of reactivation in survivors. Here, we report that B virus lacking the gD envelope glycoprotein infects both human and monkey cells as efficiently as wild-type B virus. These data provide evidence for a novel mechanism(s) utilized by B virus to gain access to target cells. This mechanism is different from those used by its close relatives, HSV-1 and -2, where gD is a pivotal protein in the virus entry process. The possibility remains that unidentified receptors, specific for B virus, permit virus entry into target cells through gD-independent pathways. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of B virus entry may help in developing rational therapeutic strategies for the prevention and treatment of B virus infection in both macaques and humans.

INTRODUCTION

Alphaherpesviruses share a strategy to enter host cells (1–3). Initial cell attachment of free virions is mediated by glycoprotein C (gC) and/or gB binding to cell surface heparan sulfate (4). This interaction facilitates specific binding of gD to one of several cellular receptors. To date, five gD receptors have been identified, including herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM, or HveA), nectin-1 (HveC), nectin-2 (HveB), poliovirus receptor (PVR, or HveD), and 3-O-sulfated heparin sulfate (5–8). Receptor binding induces a conformational change in gD and subsequent transition into an active state. Activated gD then induces gB and gH-gL conformational changes, which trigger fusion between viral and cellular membranes (9). A key role of gD homologs in cell entry was established for all known alphaherpesviruses expressing the protein, including herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), pseudorabies virus (PRV), bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1), and equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1). Investigations of deletion mutants of these viruses showed that gD is essential for virus penetration into target cells (10–14). Numerous studies showing complete inhibition of virus cell entry by monoclonal gD antibodies, soluble recombinant gD protein, or soluble gD receptors further confirmed the crucial role of gD in in vitro infectivity of alphaherpesviruses (15–18). Experiments demonstrating that vaginal infection of experimental animals with HSV-1 and HSV-2 could be prevented by pretreatment of a virus inoculum with gD-specific antibody have proved the importance of gD for in vivo infectivity, as well (19–21).

B virus (Macacine herpesvirus 1), a simplexvirus native to macaques, is closely genetically related to HSV-1 and HSV-2 (22). Like other members of the genus Simplexvirus, B virus infects mucosal epithelia, the epithelial and dermal layers of the skin, and/or, ultimately, sensory neuron endings, which results in the establishment of latency in sensory ganglia (23–27). At times of active virus shedding, B virus can be transmitted to humans through bites, scratches, and other injuries inflicted by macaques (28, 29). In infected humans, B virus replicates in cells at and near the site of entry and then spreads into the central nervous system (CNS) via sensory ganglia, often causing an acute ascending encephalomyelitis with a mortality rate of ∼80% in untreated cases (27–33).

The mechanisms of B virus entry into target cells of a natural host and a human host have not been investigated in detail. Complete genome sequencing established that the envelope glycoproteins involved in alphaherpesvirus attachment and penetration, i.e., gC, gD, gB, gH, and gL, were present in the B virus genome and highly conserved, suggesting conservation of their functions in the viral replication cycle (22). Similar to HSV and animal alphaherpesviruses, B virus appears to utilize a gD-dependent entry strategy, as the alphaherpesvirus gD receptor nectin-1 can mediate B virus entry into target cells (34). Conversely, the inability of B virus gD-specific antibody to block B virus entry into host cells suggests that gD is nonessential for B virus cell entry (35). The aim of the present study was to further elucidate the role of gD in B virus infectivity.

In this report, we describe the construction of a B virus mutant in which the gD gene was replaced with a lacZ expression cassette. Viral particles lacking gD in the envelope were produced in noncomplementing Vero cells. The infectivity of gD-negative B virus was evaluated by plaque assays using noncomplementing cell lines that originated from cell types targeted by simplexviruses in particular. The adsorption, penetration, and replication kinetics of gD-negative B virus in Vero cells were compared to those of a parental wild-type (wt) B virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses, cells, and media.

Vero (ATCC [Manassas, VA] CCL-81), HEp-2 (human epidermoid carcinoma contaminant of HeLa cells; ATCC CCL-23), LLC-MK2 (rhesus macaque kidney cells; ATCC CCL-7.1), VD60 (Vero cells stably transformed with the HSV-1 gD gene; kindly provided by Patricia G. Spear, Northwestern University, with permission from David C. Johnson), and U373 (human glioblastoma cells; kindly provided by Ian Mohr, NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY) cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) (ATCC CRL-2097, passages 7 to 9) were cultured in Eagle's minimum essential medium (EMEM) with 1% nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 10% FBS. Rhesus macaque fibroblasts (RMF) isolated from rhesus macaque dermal explants were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS. Skin was provided through the tissue-sharing program of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (Atlanta, GA) from necropsied rhesus macaques. The B78H1-C10 mouse melanoma cell line expressing human nectin-1 (kindly provided by Gary H. Cohen and Roselyn J. Eisenberg, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) was grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 500 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The B virus laboratory strain E2490 (a kind gift from the late R. N. Hull, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) was propagated in Vero cells using DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS. Cell lysate stocks of B virus were prepared by infection of Vero or VD60 monolayers as previously described (36), and infectious virus was quantified by plaque assay. HSV-1 strain KOS (ATCC VR-1493) was grown and titrated on Vero cells maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 2% FBS. During these investigations, B virus was categorized as a select agent by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS); thus, all experiments were done in accordance with relevant Health and Human Services (HHS) (64, 65) and DHS regulations in the Viral Immunology Center biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratory of Georgia State University prior to 2007 and BSL-4 laboratory following that date.

Construction and isolation of the recombinant virus.

The B virus wt strain E2490 was used for the construction of a gD deletion mutant as detailed in Fig. 1. Cloning of the KpnI DNA genomic fragments of B virus was described previously (22). Two plasmids, pK41 and pK8, that contained the gD gene and flanking sequences were used for the preparation of the transfer plasmid pKDdelZ, in which the region containing a major portion of the gD gene and adjacent promoter (nucleotides 141134 to 142027 in the B virus genomic sequence; GenBank accession no. AF533768) was replaced by a cytomegalovirus promoter-driven β-galactosidase (β-Gal) gene (a lacZ expression cassette) from plasmid pcDNA3.1/V5-His/lacZ (Invitrogen, CA). To make pKDdelZ, the three restriction fragments, i.e., the 2,126-bp Kpn-DraI fragment from pK41, the 1,648-bp SphI-XhoI fragment from pK8, and the 4,136-bp NruI-SphI fragment from pcDNA3.1/V5-His/lacZ, were inserted into a KpnI- and SalI-digested vector, pUC19. The presence of different restriction sites at the ends of each fragment allowed ligation in the defined order into the vector. All junctions between the ligated fragments in pKDdelZ were verified by DNA sequence analysis. B virus genomic DNA and linearized pKDdelZ plasmid DNA (1.5 μg each) were cotransfected into the gD-complementing cell line VD60 by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. At 96 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed by two freeze-thaw cycles, and the resultant virus stock was titrated on VD60 cells. After staining under X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) containing agarose overlays, blue recombinant virus plaques were picked and plaque purified five times on VD60 cells. The following primers were used for insertion verification by PCR of viral DNA isolated from the plaque-purified recombinant virus: LacZ-3835F (5′-CGAAGGTAAGCCTATCCCTAAC-3′), the B virus gD primers gD-F (5′-GAGTACGTGCCGGTGGAGC-3′) and gD-R (5′-GCCCTGGATGGTGACGTCG-3′), the HSV-1 gD primers gD1-F (5′-AAATATGCCTTGGCGGATGC-3′) and gD1-R (5′-CATGTTGTTCGGGGTGGC-3′), and the B virus gK primers gK-F (5′-GCGAACCCCGCCCACCG-3′) and gK-R (5′-GGAGCAGCAGCGACCGCAGAT-3′). All PCR amplifications with the primers listed above were performed using HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at 60°C annealing temperature with a 1-min extension time. Two viral stocks were produced, BV-ΔgDZ on Vero cells and BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+ on VD60 cells.

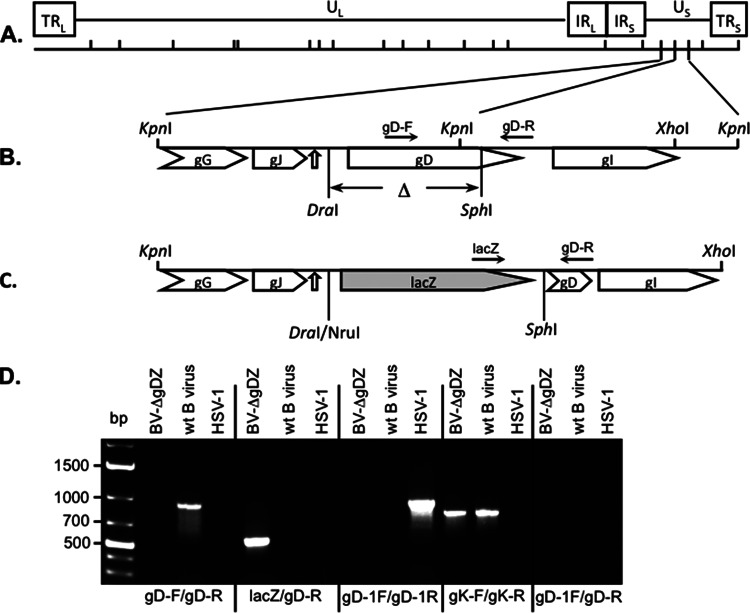

FIG 1.

Generation of the gD deletion mutant BV-ΔgDZ. (A) Schematic map of the wt B virus genome showing the unique long (UL) and unique short (US) regions, the terminal long (TRL) and short (TRS) repeats, the inverted long (IRL) and short (IRS) repeats, and the locations of the KpnI restriction sites. (B) Structure of the adjacent KpnI fragments, K41 and K8, containing the gD ORF. The pointed rectangles indicate the ORF locations. The gD segment between the DraI and SphI sites that was deleted in the recombinant virus (Δ) is shown. The open arrow points to the location of the shared polyadenylation signal for gG and gJ, which was not disrupted in the recombinant virus by the lacZ insertion. (C) Structure of the region, indicated in panel B, in the recombinant plasmid and recombinant virus in which the gD-containing DraI-SphI fragment was replaced with the NruI-SphI fragment containing the Escherichia coli lacZ gene under the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) promoter. The solid arrows indicate the locations of the diagnostic primers. (D) PCR analysis of the gD deletion mutant. Total DNA was isolated from wt B virus-, BV-ΔgDZ-, or HSV-1-infected Vero cells and amplified by PCR using the indicated primers. The positions of DNA molecular size markers are shown on the left side.

Antibodies and antisera.

B virus gB-, gD-, gG-, and gI-specific polyclonal antibodies were prepared by immunization of New Zealand White rabbits with the B virus recombinant proteins (37). A pool of rhesus B virus antibody-positive sera was kindly provided by the National B Virus Resource Laboratory (Atlanta, GA). HSV-1 gD-specific mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) (catalog no. 13-119-100) was purchased from Advanced Biotechnologies Inc. (Columbia, MD). All procedures with animals were done in strict accordance with an IACUC-approved protocol ensuring the health and humane well-being of each rabbit employed.

Western blot analysis.

B virus-infected and uninfected cell lysates were prepared according to the method of Katz et al. (38). Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (39). Briefly, proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, San Francisco, CA) for immunodetection. Rabbit sera were used at a dilution of 1:2,000, and HSV-1 gD MAb was used at a dilution of 1:20,000. Peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (1:40,000 dilution; Pierce Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used as a secondary antibody. Bands were visualized on Kodak X-omat film after detection with ECL Western blot detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences, San Francisco, CA).

Virus adsorption and penetration assays.

Vero cell monolayers in 6-well plates were infected at least in duplicate with approximately 200 PFU per well. For adsorption assays, virus was allowed to attach to cells for 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, or 120 min at 37°C, and then, the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), overlaid with DMEM containing 1% methylcellulose and 2% FBS, and incubated for 2 days. The rate of adsorption was calculated as the ratio of the average number of plaques at the indicated times relative to the average number of plaques at 120 min and was expressed as a percentage. A penetration assay was performed according to the procedure described for HSV-1 (40). A virus stock diluted in ice-cold medium was added to plates that were prechilled at 4°C for 30 min and allowed to adsorb to cells for 90 min at 4°C. The cells were then rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS, overlaid with warm medium, and shifted to 37°C to allow virus penetration to proceed. At selected times after the temperature shift (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 40, or 60 min), each of two duplicate wells was treated with either low-pH citrate buffer (10 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, 40 mM citric acid, pH 3.0) to determine the number of penetrated virions (resistant to low- pH inactivation) or PBS to determine the total number of cell surface-bound virions. After 2 min incubation with citrate buffer or PBS, the wells were washed twice with PBS, overlaid with DMEM containing 1% methylcellulose and 2% FBS, and incubated for 2 days. The rate of penetration was calculated as the ratio of the average number of plaques on citrate-treated monolayers relative to the average number of plaques on PBS-treated monolayers at each time point and was expressed as a percentage.

Plaque immunostaining and X-Gal staining.

Cell monolayers were infected with wt B virus or BV-ΔgDZ, incubated for 48 h, and then either fixed with cold methanol and immunostained with rabbit B virus gD- or gB-specific antiserum (1:200 dilution), as previously described (35), or fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde-0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS and stained with X-Gal by using a β-Gal staining set (Roche) as indicated in the manufacturer's protocol.

Analysis of viral replication kinetics.

Multistep growth curves were performed as follows. Subconfluent (85 to 90%) Vero cell monolayers grown in 12-well plates were infected with either wt B virus or BV-ΔgDZ at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 PFU/cell. The viruses were plated in duplicate on separate culture plates for each time point. After adsorption at 37°C for 1 h, the cell monolayers were rinsed with PBS, overlaid with 1 ml of medium (set as 0 h on the time scale), and returned to a 37°C humidified incubator (5% CO2). At selected time points (0, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection [p.i.]), infected cells were harvested by placing the plates on dry ice, followed by a short freeze-thaw procedure and scraping the cells into medium. Virus in the collected lysates was quantified by titration on Vero cells in duplicate. Each value on the resulting growth curves represents the average titer calculated from two independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

RESULTS

Construction of the gD deletion virus.

To investigate the role of gD in B virus infectivity, a gD deletion mutant virus was generated by replacing the gD gene in the wt B virus strain (E2490) with the bacterial β-galactosidase gene (lacZ) via homologous recombination in transfected cells. We constructed a recombinant plasmid, pKDdelZ, containing the B virus genomic region between the KpnI site at position 141134 and the XhoI site at 143675, in which the 894-bp DraI-SphI fragment was exchanged for a lacZ cassette-containing 4,136-bp NruI-SphI fragment from pcDNA3.1/V5-His/lacZ, as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1). This mutation resulted in the deletion of more than 60% of the 5′ end of the gD open reading frame (ORF) and the 162-bp upstream region predicted to contain the gD promoter, leaving the remaining portion of the gD gene nonfunctional.

On the assumption that gD might be required for B virus infectivity, we used a complementing cell line, VD60, for the isolation of the B virus gD deletion mutant. The VD60 cell line was derived from Vero cells stably transfected with the HSV-1 gD gene under its own promoter, and as a result, gD expression occurs only upon infection with either HSV-1 or HSV-2 (10). To test whether B virus is also capable of inducing HSV-1 gD expression, we either infected VD60 cell monolayers with wild-type B virus or mock infected them, and then performed Western blot analysis of HSV-1 gD protein expression using a gD1-specific MAb. As expected, HSV-1 gD was detected only in cells infected with B virus, indicating that the HSV-1 gD promoter was responsive to B virus transcription factors (data not shown). The results of these experiments verified that VD60 cells were useful as a complementing cell line for the preparation of B virus lacking gD.

To generate a mutant virus lacking gD, pKDdelZ plasmid DNA and B virus genomic DNA were cotransfected into VD60 cells, and recombinant blue plaques were selected after staining with X-Gal and five rounds of plaque purification on VD60 cells. To verify the absence of the gD segment and insertion of the lacZ gene in the genomes of selected mutants, viral DNA was isolated from multiple purified plaques and amplified by PCR using lacZ- and gD-specific primers (the locations of the primers, lacZgD-F/gD-R and gD-F/gD-R, respectively, are shown in Fig. 1B and C). The results of PCR amplification are shown for the virus isolate BV-ΔgDZ, which was selected and plaque purified on VD60 cells and repassaged three times on Vero cells (Fig. 1D). This viral stock was used throughout the study. Because B virus gD-F is located in the deleted portion of the gD gene, amplification of BV-ΔgDZ DNA with the primer pair gD-F/gD-R did not produce a PCR product, while amplification of wt B virus DNA with the same primers generated a PCR fragment with the expected size of 921 bp. Conversely, amplification of BV-ΔgDZ DNA with the lacZ-F/gD-R primer combination generated a predicted PCR product of 563 bp, whereas no amplification was detected with wt B virus DNA. To demonstrate that no recombination of the HSV-1 gD gene into the BV-ΔgDZ genome occurred after propagation of this recombinant B virus on VD60 cells, BV-ΔgDZ DNA was amplified by PCR with the HSV-1-specific gD primers (gD-1F/gD-1R) or the combination of HSV-1 gD forward (gD1-F) and B virus gD reverse (gD-R) primers. No amplification was observed for BV-ΔgDZ or wt B virus, while a PCR fragment of the expected size of 945 bp was detected after amplification of HSV-1 DNA with gD-1F/gD-1R. Additionally, no bands were detected for wt B virus, BV-ΔgDZ, or HSV-1 DNA templates after amplification with gD-1F/gD-R primers. The specific PCR product of 810 bp was observed after amplification of BV-ΔgDZ or wt B virus DNA with B-virus-specific gK primers, demonstrating that there were no PCR inhibitors in the B virus DNA preparations. These data confirmed the correct insertion of the lacZ gene, the deletion of the 5′ part of the gD gene, and the lack of recombination of the HSV-1 gD gene into the genome of the BV-ΔgDZ mutant.

Characterization of recombinant B virus stocks produced on VD60 and Vero cells.

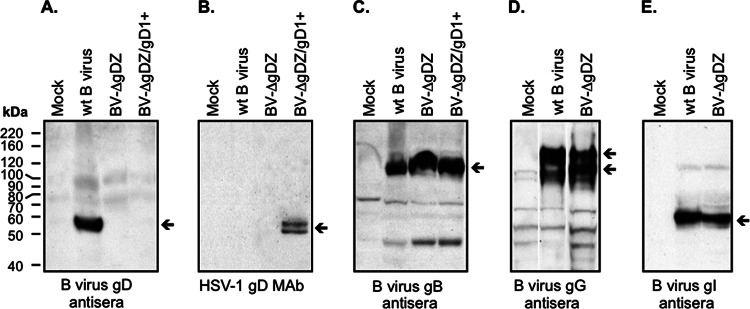

We produced two stocks of the gD deletion mutant for the subsequent experiments. One virus stock, phenotypically gD1-complemented BV-ΔgDZ (designated BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+), was prepared using VD60 cells and therefore contained HSV-1 gD protein in the B virus envelope while lacking a functional gD gene in the genome. The second virus stock, gD-negative BV-ΔgDZ, was prepared using Vero cells and therefore lacked both a gD protein in the virion and the intact gD gene. An aliquot from each of the wt B virus, BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+, and BV-ΔgDZ cell lysate stocks was examined for the presence of either B virus gD, HSV-1 gD, or B virus gB (positive control) by Western blotting using the corresponding antibodies (Fig. 2A to C). B virus gD protein was absent in both the prepared recombinant B virus stocks but was easily detectable in cell lysates infected with wt B virus as a 56-kDa immunoreactive band. These data confirmed that the produced stocks indeed lacked B virus gD protein and were not contaminated with wt virus. As expected, HSV-1 gD MAb revealed an ∼56-kDa double band of HSV-1 gD only in the BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+ stock prepared in VD60 cells. A 120-kDa B virus gB band of comparable intensity was observed in each of the B virus stocks. No viral proteins were detected in mock-infected cells.

FIG 2.

Expression of B virus glycoproteins in cells infected with the recombinant virus. Mock-infected Vero cell lysates, cell lysates of the stocks of wt B virus and BV-ΔgDZ prepared in Vero cells, and BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+ prepared in VD60 cells, each containing 10 μg total protein, were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto membranes, and then probed with the rabbit B virus gD antiserum (A), HSV-1 gD MAb (B), rabbit B virus gB antiserum (C), B virus gG antiserum (D), or B virus gI antiserum (E). The arrows on the right side of each panel point to the specific immunoreactive proteins. The positions of protein molecular mass standards are indicated on the left.

Expression of genes adjacent to gD in BV-ΔgDZ-infected cells.

In the recombinant plasmid prepared, the B virus flanking fragments contained the gG and gJ genes on one side and the gI gene on the other side (Fig. 1A to C). To ensure that the expression of these genes in the recombinant virus was not affected as a result of recombination events, aliquots from the BV-ΔgDZ stock, the wt B virus stock, and the total lysate of mock-infected Vero cells were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%), transferred onto nitrocellulose, and probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for B virus gG or gI. The expression of a B virus gJ protein was not evaluated due to the lack of gJ-specific antibodies. Immunoreactive 115- and 140-kDa gG bands and a 53-kDa gI protein band of comparable intensity were observed in BV-ΔgDZ-infected and wt B virus-infected cells (Fig. 2D and E), indicating that the deletion-insertion in the gD locus did not affect the expression of either the gG or gI gene. Absence of specific reactivity with proteins in mock-infected cell lysates confirmed the specificity of the antibodies.

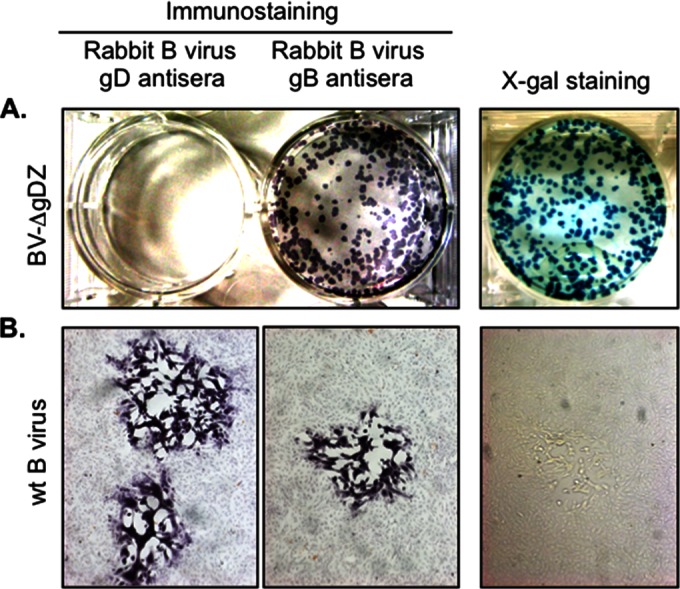

Glycoprotein D is not required for B virus entry into Vero cells.

To test whether B virus lacking gD is capable of infecting noncomplementing cells, subconfluent Vero cell monolayers were infected with either BV-ΔgDZ or wt B virus, as a positive control, and the resultant plaques were either immunostained with antibodies specific for B virus gD or gB or, alternatively, reacted with X-Gal. B virus gD mutant virus formed plaques on Vero monolayers, validating that gD is not essential for virus entry into these cells. Moreover, the plaque sizes of BV-ΔgDZ were similar to that of the parental virus, suggesting gD is not required for B virus lateral spread in Vero cells. No plaques immunoreactive with the gD antiserum were observed in the BV-ΔgDZ-infected monolayers, whereas all the plaques were stained with the gB antiserum or X-Gal, confirming the lack of gD protein and presence of β-galactosidase in recombinant B virus plaques (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, all wt B virus plaques were positively stained with both gD and gB antisera, but not with X-Gal, thus demonstrating sufficient sensitivity of immunostaining and the specificity of the X-Gal staining procedure (Fig. 3B). From these experiments, we concluded that gD is a nonessential protein for B virus; it is not critical for Vero cell entry or direct cell-to-cell spread.

FIG 3.

Characterization of BV-ΔgDZ plaques on noncomplementing Vero cells. Vero cell monolayers were infected with BV-ΔgDZ (A) or wt B virus (B). The cells were fixed at 48 h p.i. and then either X-Gal stained or immunostained with rabbit B virus gD- or gB-specific antibody (positive control), as described in Materials and Methods. The images in panel B were acquired with an ×5-magnification objective.

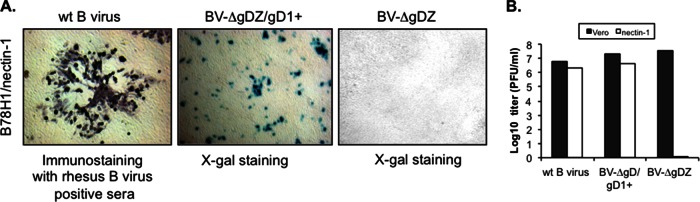

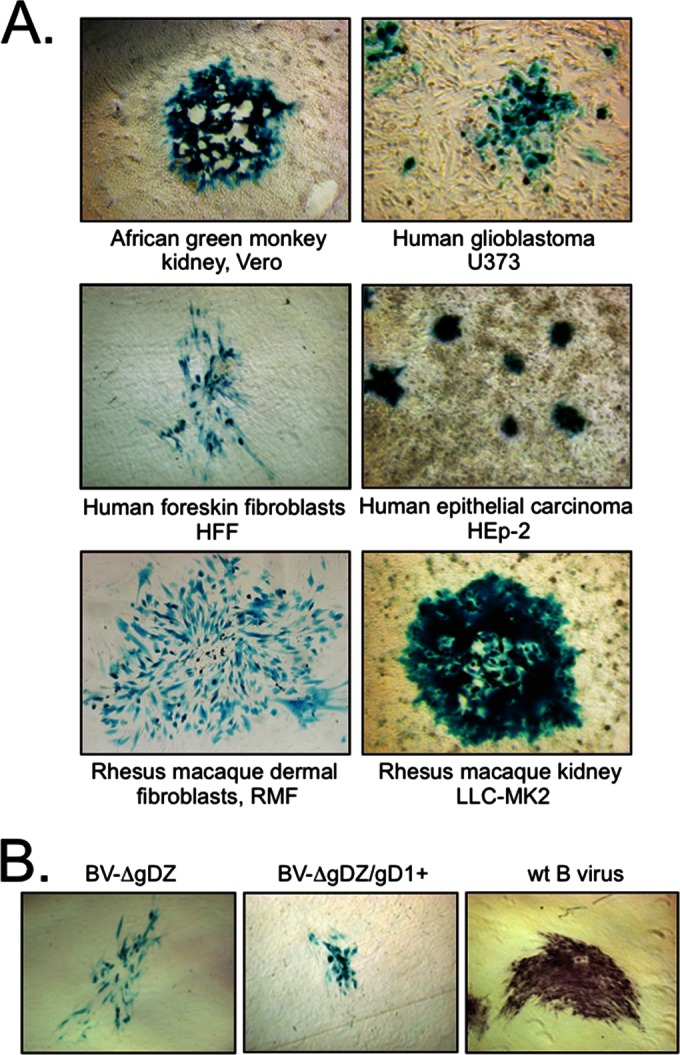

HSV-1 gD can complement gD-negative B virus for cell entry.

To examine whether HSV-1 gD is capable of mediating B virus entry when incorporated into B virus envelope, we examined the ability of phenotypically gD1-complemented BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+ virus to infect B78H1 cells bearing a single specific gD receptor, human nectin-1 (HveC). We reasoned that the cell line was an appropriate system to analyze gD1 functionality in the B virus background, because expression of human nectin-1 allows gD-specific entry of wt B virus into B78H1 cells that are otherwise resistant to infection, most likely due to the inability of murine homologs of entry receptors to mediate B virus entry (our unpublished data). Cell monolayers were infected with BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+, BV-ΔgDZ, or wt B virus (as a positive control), and then, after 2 days incubation under a semisolid overlay, either stained with X-Gal or, in the case of wt infection, immunostained with pooled rhesus B virus antibody-positive sera. Consistent with the previously published results (34), as well as our own unpublished observations, wt B virus was able to enter cells engineered to express human nectin-1 as the only entry mediator and to form large semisyncytial plaques (Fig. 4A). In contrast, BV-ΔgD failed to infect these cells further, confirming that BV-ΔgDZ virions produced in Vero cells indeed lacked any functional gD protein. On the other hand, only single X-Gal-stained cells, not plaques, were observed in the monolayers infected with gD1-complemented BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+. The titers of gD1-complemented B virus on Vero and B78H1/nectin1 cells were comparable to those of wt virus (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that HSV-1 gD restores the entry defect of the B virus gD deletion mutant and does not affect B virus replication, but sustained expression of gD is required for efficient B virus cell-to-cell transmission via human nectin-1 expressed in mouse cells.

FIG 4.

Infectivity of mutant B virus on B78H1/nectin-1 and Vero cells. (A) Monolayers of B78H1 cells expressing human nectin-1 were infected with wt B virus or BV-ΔgDZ or BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+ virus. After 2 days, the monolayers were fixed and immunostained with rhesus B virus antibody-positive serum or stained with X-Gal. The images were acquired with an ×5-magnification objective. (B) BV-ΔgDZ, BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+, and wt B virus were titrated on Vero and B78H1/nectin-1 cells by a plaque assay.

Adsorption, penetration, and replication kinetics of BV-ΔgDZ in Vero cells.

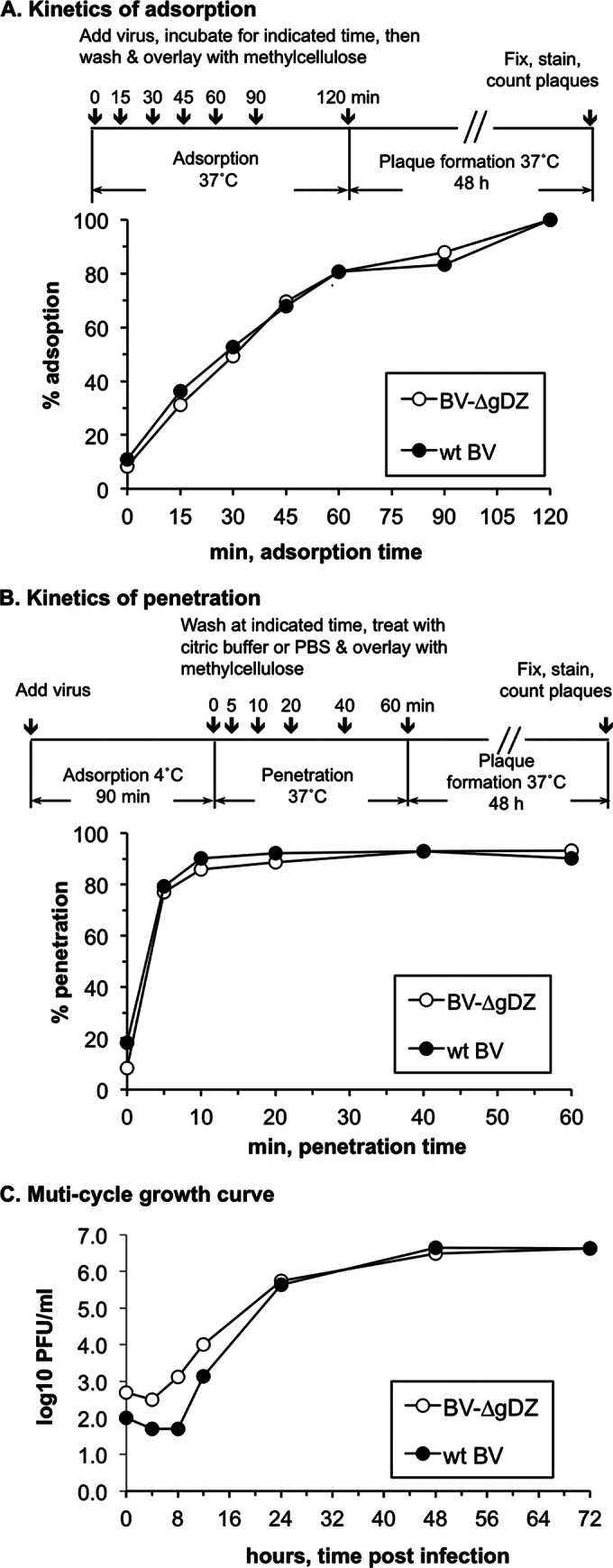

To investigate the effects of the gD deletion on the initial steps of B virus infection in cultured cells, we compared the adsorption and penetration kinetics of the parental virus and BV-ΔgDZ in Vero cells (Fig. 5A and B). For both viruses, the number of cell-bound virions increased exponentially during the first 60 min and then slowly approached a plateau during the next hour. After adsorption, each virus entered cells very rapidly, reaching almost 80% penetration in the first 5 min after the temperature shift. These data clearly indicate that neither adsorption nor penetration rates differ between mutant and wt viruses.

FIG 5.

Growth characteristics of BV-ΔgDZ. Growth properties of BV-ΔgDZ and wt B virus (wt BV) were compared by assessing kinetics of virus adsorption (A), penetration (B), and replication (C) in Vero cells. In adsorption and penetration assays, each cell monolayer was infected with ∼200 PFU of either parental or mutant virus. The kinetics of adsorption was assayed by a temperature shift from 4°C to 37°C. The kinetics of penetration was assayed by determining the proportion of cells resistant to low-pH inactivation compared to a PBS-treated control at different times after the temperature shift (% penetration). For the multistep growth curve, Vero cells were infected with either parental or mutant virus at an MOI of 0.01 PFU/ml. Viruses were harvested at the indicated time points and titrated on Vero cells.

To examine whether the gD deletion affected postentry steps of the B virus replicative cycle, we compared the replication kinetics of BV-ΔgDZ and wt B viruses in Vero cells. Multistep growth curves of each virus showed nearly identical replication kinetics and endpoint titers of progeny virus (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate for the first time that B virus gD is dispensable for virion attachment and penetration, as well as for efficient replication of B virus in Vero cells.

Infectivity of BV-ΔgDZ on various target cells.

We evaluated the ability of gD-negative B virus to infect and form plaques on additional noncomplementing cultures, including human epithelial carcinoma HEp-2 cells, LLC-MK2 rhesus kidney cells, U373 human glioblastoma cells, and the primary cells RMF and HFFs. Vero cells were used for positive controls. Cell monolayers were infected with 10-fold serial dilutions of either gD-negative, gD1-supplemented, or wt B virus stocks, overlaid with semisolid agarose, and subsequently stained with X-Gal or immunostained 48 h later. Both gD-negative and gD1-supplemented BV-ΔgDZ mutants were able to infect all tested cell lines and form plaques (Fig. 6A; results are shown for gD-negative virus only). The plaque sizes of both wt and mutant viruses on matching cell monolayers were similar, with one exception: on HFFs, wt plaques were ∼2 to 3 times larger than those of gD-negative and gD1-supplemented BV-ΔgDZ (Fig. 6B). The titers of all viruses on matching cell lines were comparable (Table 1), indicating that B virus replication was not affected by either the gD deletion or replacement with HSV-1 gD in the examined cell lines. These data indicate that, at least in cell culture, B virus can use a gD-independent mechanism to enter and replicate in epithelial cells, dermal fibroblasts, and neuronal cells. The data also suggest that B virus cell spread in these cell lines does not require gD but that gD can facilitate spread when present, e.g., in HFFs.

FIG 6.

Infectivity of BV-ΔgDZ on noncomplementing cell cultures. (A) The indicated cell monolayers were exposed to BV-ΔgDZ virus, maintained under semisolid overlay for 48 h, and then fixed and stained with X-Gal. The images were acquired with an ×10-magnification objective for U373 cells and an ×5-magnification objective for other cell types. (B) Plaque morphology of BV-ΔgDZ, BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+, and wt B virus on HFFs. At 48 h p.i., the plaques produced by recombinant viruses were stained with X-Gal; wt B virus-formed plagues were immunostained with pooled macaque B virus immune sera. The images were acquired with an ×5-magnification objective.

TABLE 1.

Titers of wild-type B virus and gD-negative BV-ΔgDZ and gD1-supplemented BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+ on different target cells

| Virusa | Titer (log10 PFU/ml)b on: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vero | LLC-MK2 | HEp-2 | U373 | RMF | HFF | |

| Wt BV (E2490) | 7.2 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 7.1 | 6.3 |

| BV-ΔgDZ | 7.4 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 7.3 | 6.0 |

| BV-ΔgDZ/gD1+ | 7.3 | 6.6 | 6.6 | ND | ND | 6.4 |

The input virus was not adjusted for different efficiencies of plating of B virus in each cell line.

Viruses were titrated on the indicated cell monolayers in duplicate. The mean values are shown. ND, not done.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the construction of the B virus gD deletion mutant BV-ΔgDZ and demonstrate for the first time that gD is not required for B virus infectivity in cultured cells representative of those the virus encounters at the site of entry in macaques and humans. Originally, the hypothesis that B virus enters host cells via a gD-independent pathway was based on indirect evidence obtained from B virus neutralization experiments. We reported that B virus gD-specific polyclonal antibodies lacked the capacity to block B virus entry into Vero cells (35). The data from the present study provide direct support for the hypothesis. Here, we established that the gD-null mutant entered target cells as efficiently as wt virus, as evidenced by comparable titers of wt and gD-null mutants on monolayers of noncomplementing cell lines derived from cell types targeted by simplexviruses, i.e., epithelial cells (Vero, LLC-MK2, and Hep-2) and dermal fibroblasts (HFFs and RMF), as well as in neuronal cell (U373) cultures. Additionally, the ability of phenotypically gD-negative BV-ΔgDZ virions to form wt-like plaques on Vero, LLC-MK2, and Hep-2 cells and RMF suggests that gD is not required for the spread of cells targeted by the virus. We observed, however, that BV-ΔgDZ produced plaques smaller than those produced by wt B virus in HFFs, suggesting that requirements for entry or lateral B virus spread in some target cells likely differ. We have also shown that BV-ΔgDZ was indistinguishable from the parental virus with regard to attachment, penetration, replication rates, and virus yields in Vero cells. Thus, our data show for the first time that B virus gD is dispensable for B virus infectivity.

In marked contrast, gD is absolutely essential for entry of other neurotropic alphaherpesviruses that encode functional gD, i.e., HSV-1, PRV-1, BHV-1, and EHV-1, although in PRV, it is nonessential for cell-to-cell spread and neuroinvasion (13, 14, 41). Using gD deletion mutants of these viruses, investigators previously established that viral particles lacking envelope gD fail to penetrate target cells while maintaining the ability to attach to the cell surface (10–14). Not all viruses in the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, however, have or express the gD gene. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) lacks the gD gene homolog in the genome (42), while Marek's disease virus (MDV) lacks detectable gD expression due to a transcriptional defect of the gene (43, 44). Obviously, given the absence of gD homologs, there are no gD-dependent pathways for the cell entry and spread of these viruses (45–47).

B virus, unlike VZV and MDV, produces substantial amounts of gD in infected cell cultures (35). Moreover, B virus-infected macaques typically generate high-titer gD-specific antibody (37), suggesting robust gD production during natural infection, as well. Several lines of evidence, such as the ability of wt B virus to enter cells bearing a single gD receptor, the ability of gD-specific antibodies to inhibit B virus infectivity on these cells, and failure of a gD-negative mutant to infect nectin-1-expressing cells, strongly suggest that gD protein of B virus is indeed functionally active. In addition, HSV-1 gD can functionally replace the B virus gD when incorporated into BV-ΔgDZ virions. This observation provides further support for the notion that the gD function as a cell entry mediator is conserved in B virus, although it is nonessential. Thus, among herpesviruses expressing gD protein, B virus is unique, because gD is fully functional, but not essential for entry into the major cell targets, including epithelial cells and fibroblasts. There are at least two possible reasons why gD is maintained in B virus despite the fact that it is dispensable for infectivity. First, gD might be required for B virus entry into some specific cell targets not tested in this study (e.g., CNS neurons) or for spread (e.g., retrograde or anterograde transneuronal spread). Second, gD might perform essential in vivo functions, such as suppression of NK cell-mediated lysis of infected cells (48) or modulation of innate antiviral responses (49).

We propose that B virus evolutionarily selected for a unique gD-independent entry mechanism while still maintaining the ability to use gD-mediated pathways, in view of our data presented here. One scenario is that, in addition to gD, another envelope glycoprotein(s) of B virus was selected for entry during evolution and divergence, possibly broadening B virus tissue tropism, or even the host range. Demonstration of gD-independent infectivity, as in experimentally induced gD-negative PRV and BHV-1 infections by repeated copassaging of infected and noninfected cells, illustrates that under selective pressure, certain viral proteins essential to the infectivity of closely related simplexviruses may play a different, nonessential role during virus and host divergence (50–54). Interestingly, the acquired gD-independent infectivity of PRV and BHV-1 has been linked to compensatory mutations in gB and gH, suggesting that some forms of these glycoproteins substitute for gD function as cell receptor binding proteins. Additionally, Uchida and colleagues demonstrated that ineffective gD function of an HSV-1 gD mutant defective for nectin-1 binding can be efficiently compensated for by the D285N/A549T double mutation in gB (55). The D285 and A549 residues are conserved in B virus gB, and therefore, gD-independent infectivity of B virus is not linked to the mutations in these positions. This conservation is maintained regardless of the species of macaque from which the virus is isolated (data not shown). Detailed analysis of the residues in gH/gL, gB, or other glycoproteins may help to identify unconventional entry receptors that permit gD-independent entry of B virus.

Several HSV-1 gB receptors capable of mediating HSV-1 cell entry have been recently described. At least one putative receptor for HSV-1 gB is paired Ig-like type 2 receptor alpha (PILRα) (56, 57). However, it is highly unlikely that PILRα serves as a receptor for B virus entry, because CHO cells expressing human PILRα failed to become infected with B virus (34). In addition, myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) and nonmuscle myosin IIA and IIB (NMHC-IIA and NMHC-IIB, respectively) isoforms have been reported to bind HSV-1 gB and to serve as entry receptors for HSV-1 (56–60). HSV-1 gH has also been shown to interact with cellular receptors (αVβ3, αVβ6, and αVβ8 integrins) and to facilitate viral entry (61–63). Future investigations of gB and gH functions in B virus infectivity are essential to determine whether these proteins can, in fact, mediate gD-independent B virus entry, particularly because blocking entry of B virus may be an effective way to diminish or prevent the devastating effects of zoonotic B virus infection.

In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time that glycoprotein D is not essential for infectivity of B virus in cultured human and nonhuman primate cells. We have also shown that HSV-1 gD can fully complement gD-negative B virus for cell entry via nectin-1 receptors, thus confirming that gD entry pathways are indeed conserved in B virus. Our data suggest for the first time that B virus evolutionary selection resulted in an additional or alternative entry pathway that does not require gD, and unlike other members of the subfamily, B virus appears to use at least two different entry mechanisms. The significance of each pathway for B virus infectivity in vivo is presently unknown and requires further investigation. Identification of the distinctive B virus-specific entry mechanisms is likely to shed light on causes of the unique pathogenicity of this deadly zoonotic agent in infected humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Patricia G. Spear and David C. Johnson for providing VD60 cells stably transfected with the HSV-1 gD gene, Gary H. Cohen and Roselyn J. Eisenberg for providing B78H1 mouse cells expressing HSV entry receptors, and Ian Mohr for the gift of U373 cells. We thank Peter Krug for providing NaI gradient-purified genomic DNA of B virus. We also acknowledge support and resources from the National B Virus Resource Center in the Viral Immunology Center of Georgia State University and the tissue-sharing resources of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, funded by NIH grant P51OD011132.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants NIH P40 RR05062 and R01 RR03162 from the NIH's National Center for Research Resources and by the generous and continued support of the Georgia Research Alliance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spear PG, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. 2000. Three classes of cell surface receptors for alphaherpesvirus entry. Virology 275:1–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campadelli-Fiume G, Cocchi F, Menotti L, Lopez M. 2000. The novel receptors that mediate the entry of herpes simplex viruses and animal alphaherpesviruses into cells. Rev Med Virol 10:305–319. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spear PG, Longnecker R. 2003. Herpesvirus entry: an update. J Virol 77:10179–10185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10179-10185.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shukla D, Spear PG. 2001. Herpesviruses and heparan sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J Clin Invest 108:503–510. doi: 10.1172/JCI13799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geraghty RJ, Krummenacher C, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Spear PG. 1998. Entry of alphaherpesviruses mediated by poliovirus receptor-related protein 1 and poliovirus receptor. Science 280:1618–1620. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cocchi F, Menotti L, Mirandola P, Lopez M, Campadelli-Fiume G. 1998. The ectodomain of a novel member of the immunoglobulin subfamily related to the poliovirus receptor has the attributes of a bona fide receptor for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human cells. J Virol 72:9992–10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warner MS, Geraghty RJ, Martinez WM, Montgomery RI, Whitbeck JC, Xu R, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Spear PG. 1998. A cell surface protein with herpesvirus entry activity (HveB) confers susceptibility to infection by mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and pseudorabies virus. Virology 246:179–189. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shukla D, Liu J, Blaiklock P, Shworak NW, Bai X, Esko JD, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Rosenberg RD, Spear PG. 1999. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell 99:13–22. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krummenacher C, Supekar VM, Whitbeck JC, Lazear E, Connolly SA, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Wiley DC, Carfi A. 2005. Structure of unliganded HSV gD reveals a mechanism for receptor-mediated activation of virus entry. EMBO J 24:4144–4153. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ligas MW, Johnson DC. 1988. A herpes simplex virus mutant in which glycoprotein D sequences are replaced by beta-galactosidase sequences binds to but is unable to penetrate into cells. J Virol 62:1486–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Csellner H, Walker C, Wellington JE, McLure LE, Love DN, Whalley JM. 2000. EHV-1 glycoprotein D (EHV-1 gD) is required for virus entry and cell-cell fusion, and an EHV-1 gD deletion mutant induces a protective immune response in mice. Arch Virol 145:2371–2385. doi: 10.1007/s007050070027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauh I, Mettenleiter TC. 1991. Pseudorabies virus glycoproteins gII and gp50 are essential for virus penetration. J Virol 65:5348–5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fehler F, Herrmann JM, Saalmèuller A, Mettenleiter TC, Keil GM. 1992. Glycoprotein IV of bovine herpesvirus 1-expressing cell line complements and rescues a conditionally lethal viral mutant. J Virol 66:831–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peeters B, de Wind N, Hooisma M, Wagenaar F, Gielkens A, Moormann R. 1992. Pseudorabies virus envelope glycoproteins gp50 and gII are essential for virus penetration, but only gII is involved in membrane fusion. J Virol 66:894–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuller AO, Spear PG. 1987. Anti-glycoprotein D antibodies that permit adsorption but block infection by herpes simplex virus 1 prevent virion-cell fusion at the cell surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84:5454–5458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Highlander SL, Sutherland SL, Gage PJ, Johnson DC, Levine M, Glorioso JC. 1987. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies specific for herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D inhibit virus penetration. J Virol 61:3356–3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicola AV, Ponce de Leon M, Xu R, Hou W, Whitbeck JC, Krummenacher C, Montgomery RI, Spear PG, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. 1998. Monoclonal antibodies to distinct sites on herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D block HSV binding to HVEM. J Virol 72:3595–3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitbeck JC, Muggeridge MI, Rux AH, Hou W, Krummenacher C, Lou H, van Geelen A, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. 1999. The major neutralizing antigenic site on herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D overlaps a receptor-binding domain. J Virol 73:9879–9890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeitlin L, Whaley KJ, Sanna PP, Moench TR, Bastidas R, De Logu A, Williamson RA, Burton DR, Cone RA. 1996. Topically applied human recombinant monoclonal IgG1 antibody and its Fab and F(ab′)2 fragments protect mice from vaginal transmission of HSV-2. Virology 225:213–215. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linehan MM, Richman S, Krummenacher C, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Iwasaki A. 2004. In vivo role of nectin-1 in entry of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2 through the vaginal mucosa. J Virol 78:2530–2536. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2530-2536.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, Dave SK, Simmons A. 2004. Prevention of genital herpes in a guinea pig model using a glycoprotein D-specific single chain antibody as a microbicide. Virol J 1:11. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perelygina L, Zhu L, Zurkuhlen H, Mills R, Borodovsky M, Hilliard JK. 2003. Complete sequence and comparative analysis of the genome of herpes B virus (cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) from a rhesus monkey. J Virol 77:6167–6177. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6167-6177.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keeble SA, Christofinis GJ, Wood W. 1958. Natural B virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J Pathol Bacteriol 76:189–199. doi: 10.1002/path.1700760121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeble SA. 1960. B virus infection in monkeys. Ann N Y Acad Sci 85:960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boulter EA. 1975. The isolation of monkey B virus (Herpesvirus simiae) from the trigeminal ganglia of a healthy seropositive rhesus monkey. J Biol Stand 3:279–280. doi: 10.1016/0092-1157(75)90031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vizoso AD. 1975. Recovery of herpes simiae (B virus) from both primary and latent infections in rhesus monkeys. Br J Exp Pathol 56:485–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitley RJ, Hilliard JK. 2001. Cercopithecine herpesvirus (B virus), p 2835–2848. In Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson WL, Hummeler K. 1960. B virus infection in man. Ann N Y Acad Sci 85:970–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer AE. 1987. B virus, Herpesvirus simiae: historical perspective. J Med Primatol 16:99–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabin AB, Wright WM. 1934. Acute ascending myelitis following a monkey bite, with isolation of a virus capable of reproducing the disease. J Exp Med 59:115–136. doi: 10.1084/jem.59.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gay FP, Holden M. 1933. Isolation of herpes virus from several cases of epidemic encephalitis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 30:1051–1053. doi: 10.3181/00379727-30-6788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hull RN. 1973. The simian herpesviruses, p 389–425. In Kaplan AS. (ed), The herpesviruses. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmes GP, Hilliard JK, Klontz KC, Rupert AH, Schindler CM, Parrish E, Griffin DG, Ward GS, Bernstein ND, Bean TW, Ball MR Sr, Brady JA, Wilder MH, Kaplan JE. 1990. B virus (Herpesvirus simiae) infection in humans: epidemiologic investigation of a cluster. Ann Intern Med 112:833–839. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-11-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan Q, Amen M, Harden M, Severini A, Griffiths A, Longnecker R. 2012. Herpes B virus utilizes human nectin-1 but not HVEM or PILRalpha for cell-cell fusion and virus entry. J Virol 86:4468–4476. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00041-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perelygina L, Patrusheva I, Zurkuhlen H, Hilliard JK. 2002. Characterization of B virus glycoprotein antibodies induced by DNA immunization. Arch Virol 147:2057–2073. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0889-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hilliard JK, Eberle R, Lipper SL, Munoz RM, Weiss SA. 1987. Herpesvirus simiae (B virus): replication of the virus and identification of viral polypeptides in infected cells. Arch Virol 93:185–198. doi: 10.1007/BF01310973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perelygina L, Patrusheva I, Hombaiah S, Zurkuhlen H, Wildes MJ, Patrushev N, Hilliard J. 2005. Production of herpes B virus recombinant glycoproteins and evaluation of their diagnostic potential. J Clin Microbiol 43:620–628. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.620-628.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz D, Hilliard JK, Eberle R, Lipper SL. 1986. ELISA for detection of group-common and virus-specific antibodies in human and simian sera induced by herpes simplex and related simian viruses. J Virol Methods 14:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(86)90040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perelygina L, Zurkuhlen H, Patrusheva I, Hilliard JK. 2002. Identification of a herpes B virus-specific glycoprotein D immunodominant epitope recognized by natural and foreign hosts. J Infect Dis 186:453–461. doi: 10.1086/341834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McClain DS, Fuller AO. 1994. Cell-specific kinetics and efficiency of herpes simplex virus type 1 entry are determined by two distinct phases of attachment. Virology 198:690–702. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulder W, Pol J, Kimman T, Kok G, Priem J, Peeters B. 1996. Glycoprotein D-negative pseudorabies virus can spread transneuronally via direct neuron-to-neuron transmission in its natural host, the pig, but not after additional inactivation of gE or gI. J Virol 70:2191–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davison AJ, Scott JE. 1986. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J Gen Virol 67:1759–1816. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-9-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zelnik V, Majerciak V, Szabova D, Geerligs H, Kopacek J, Ross LJ, Pastorek J. 1999. Glycoprotein gD of MDV lacks functions typical for alpha-herpesvirus gD homologues. Acta Virol 43:164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan X, Brunovskis P, Velicer LF. 2001. Transcriptional analysis of Marek's disease virus glycoprotein D, I, and E genes: gD expression is undetectable in cell culture. J Virol 75:2067–2075. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2067-2075.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parcells MS, Anderson AS, Morgan RW. 1994. Characterization of a Marek's disease virus mutant containing a lacZ insertion in the US6 (gD) homologue gene. Virus Genes 9:5–13. doi: 10.1007/BF01703430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson AS, Parcells MS, Morgan RW. 1998. The glycoprotein D (US6) homolog is not essential for oncogenicity or horizontal transmission of Marek's disease virus. J Virol 72:2548–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cole NL, Grose C. 2003. Membrane fusion mediated by herpesvirus glycoproteins: the paradigm of varicella-zoster virus. Rev Med Virol 13:207–222. doi: 10.1002/rmv.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grauwet K, Cantoni C, Parodi M, De Maria A, Devriendt B, Pende D, Moretta L, Vitale M, Favoreel HW. 2014. Modulation of CD112 by the alphaherpesvirus gD protein suppresses DNAM-1-dependent NK cell-mediated lysis of infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:16118–16123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409485111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoon M, Kopp SJ, Taylor JM, Storti CS, Spear PG, Muller WJ. 2011. Functional interaction between herpes simplex virus type 2 gD and HVEM transiently dampens local chemokine production after murine mucosal infection. PLoS One 6:e16122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schroder C, Linde G, Fehler F, Keil GM. 1997. From essential to beneficial: glycoprotein D loses importance for replication of bovine herpesvirus 1 in cell culture. J Virol 71:25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schroder C, Keil GM. 1999. Bovine herpesvirus 1 requires glycoprotein H for infectivity and direct spreading and glycoproteins gH(W450) and gB for glycoprotein D-independent cell-to-cell spread. J Gen Virol 80:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmidt J, Klupp BG, Karger A, Mettenleiter TC. 1997. Adaptability in herpesviruses: glycoprotein D-independent infectivity of pseudorabies virus. J Virol 71:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karger A, Schmidt J, Mettenleiter TC. 1998. Infectivity of a pseudorabies virus mutant lacking attachment glycoproteins C and D. J Virol 72:7341–7348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmidt J, Gerdts V, Beyer J, Klupp BG, Mettenleiter TC. 2001. Glycoprotein D-independent infectivity of pseudorabies virus results in an alteration of in vivo host range and correlates with mutations in glycoproteins B and H. J Virol 75:10054–10064. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10054-10064.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uchida H, Chan J, Goins WF, Grandi P, Kumagi I, Cohen JB, Glorioso JC. 2010. A double mutation in glycoprotein gB compensates for ineffective gD-dependent initiation of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J Virol 84:12200–12209. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01633-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Satoh T, Arii J, Suenaga T, Wang J, Kogure A, Uehori J, Arase N, Shiratori I, Tanaka S, Kawaguchi Y, Spear PG, Lanier LL, Arase H. 2008. PILRalpha is a herpes simplex virus-1 entry coreceptor that associates with glycoprotein B. Cell 132:935–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arii J, Uema M, Morimoto T, Sagara H, Akashi H, Ono E, Arase H, Kawaguchi Y. 2009. Entry of herpes simplex virus 1 and other alphaherpesviruses via the paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha. J Virol 83:4520–4527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02601-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suenaga T, Satoh T, Somboonthum P, Kawaguchi Y, Mori Y, Arase H. 2010. Myelin-associated glycoprotein mediates membrane fusion and entry of neurotropic herpesviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:866–871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913351107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arii J, Goto H, Suenaga T, Oyama M, Kozuka-Hata H, Imai T, Minowa A, Akashi H, Arase H, Kawaoka Y, Kawaguchi Y. 2010. Non-muscle myosin IIA is a functional entry receptor for herpes simplex virus-1. Nature 467:859–862. doi: 10.1038/nature09420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arii J, Hirohata Y, Kato A, Kawaguchi Y. 2015. Non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIB mediates herpes simplex virus 1 entry. J Virol 89:1879–1888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03079-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gianni T, Salvioli S, Chesnokova LS, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Campadelli-Fiume G. 2013. αvβ6- and αvβ8-integrins serve as interchangeable receptors for HSV gH/gL to promote endocytosis and activation of membrane fusion. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003806. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheshenko N, Trepanier JB, Gonzalez PA, Eugenin EA, Jacobs WR Jr, Herold BC. 2014. Herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein H interacts with integrin alphavbeta3 to facilitate viral entry and calcium signaling in human genital tract epithelial cells. J Virol 88:10026–10038. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00725-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parry C, Bell S, Minson T, Browne H. 2005. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H binds to alphavbeta3 integrins. J Gen Virol 86:7–10. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1999. Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories, 4th ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 65.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2009. Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories, 5th ed. HHS publication no. (CDC) 21-1112 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC: http://www.cdc.gov/biosafety/publications/bmbl5/index.htm. [Google Scholar]