ABSTRACT

Herpes simplex viruses (HSV) package and bring into cells an RNase designated virion host shutoff (VHS) RNase. In infected cells, the VHS RNase targets primarily stress response mRNAs characterized by the presence of AU-rich elements in their 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). In uninfected cells, these RNAs are sequestered in exosomes or P bodies by host proteins that bind to the AU-rich elements. In infected cells, the AU-rich RNAs are deadenylated and cleaved close to the AU-rich elements, leading to long-term persistence of nontranslatable RNAs consisting of the 5′ portions of the cleavage products. The host proteins that bind to the AU-rich elements are either resident in cells (e.g., TIA-1) or induced (e.g., tristetraprolin). Earlier, this laboratory reported that tristetraprolin binds VHS RNase. To test the hypothesis that tristetraprolin directs VHS RNase to the AU-rich elements, we mapped the domains of VHS and tristetraprolin required for their interactions. We report that VHS binds to the domain of tristetraprolin that enables its interaction with RNA. A single amino acid substitution in that domain abolished the interaction with RNA but did not block the binding to VHS RNase. In transfected cells, the mutant but not the wild-type tristetraprolin precluded the degradation of the AU-rich RNAs by VHS RNase. We conclude that TTP mediates the cleavage of the 3′ UTRs of stress response mRNAs by recruiting the VHS RNase to the AU-rich elements.

IMPORTANCE The primary host response to HSV infection is the synthesis of stress response mRNAs characterized by the presence of AU-rich elements in their 3′ UTRs. These mRNAs are the targets of the virion host shutoff (VHS) RNase. The VHS RNase binds both to mRNA cap structure and to tristetraprolin, an inducible host protein that sequesters AU-rich mRNAs in exosomes or P bodies. Here we show that tristetraprolin recruits VHS RNase to the AU-rich elements and enables the degradation of the stress response mRNAs.

INTRODUCTION

A key function of herpes simplex virus (HSV) gene products is to block host responses to infection. This effort takes place at several levels, by blocking the signaling that leads ultimately to interferon synthesis as well as by degradation of host macromolecules that are inimical to viral replication (1). The focus of this report is on the degradation of host mRNAs by the virion host shutoff RNase (VHS RNase). Historically, hints that HSV degrades mRNAs emerged from observations that host polyribosomes are rapidly dispersed after infection (2, 3). Direct evidence that HSV degrades mRNAs by the action of a VHS protein emerged from studies by N. Frenkel and associates (4–7). Because many of the subsequent studies in many laboratories were done in cell-free systems, the prevailing view was that VHS does not discriminate between host and viral mRNAs. In essence, the prevailing view was that the synthesis of viral mRNA outpaced its degradation until finally, at midpoint in infection, VHS was neutralized by VP16.

(i) The studies carried out in this laboratory initially demonstrated that VHS is an RNase with the specificity of RNase A (8). More relevant, the studies done on infected cells rather than in cell-free systems demonstrated the following.

(ii) In infected cells, stable mRNAs exemplified by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were rapidly and effectively degraded by the VHS RNase (9). The published data indicate that the VHS binds to and cleaves off the cap structure (10, 11). The mRNA is the rapidly degraded 5′ to 3′ (12, 13).

(iii) A totally different picture emerged in from analyses of short-lived stress response mRNAs characterized by the presence of AU-rich elements in their 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). These elements typically are present in single (class 1) or multiple (class 2) copies of pentameric (AUUUA) motifs. Their turnover is modulated by proteins that bind the AU elements (14). Included in the list of proteins that bind the AU-rich elements are tristetraprolin (TTP, ARE/poly(U)-binding/degradation factor 1 (AUF-1), KH-type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP), T-cell internal antigen 1 (TIA-1), and TIA-1-related protein (TIAR). In essence, these proteins bind the AU-rich sequences and sequester the mRNAs in exosomes or P bodies, where they are ultimately degraded (15–17). In infected cells, the AU-rich mRNAs undergo deadenylation and cleavage at the AU sequences. While the 3′ cleavage products are rapidly degraded, the 5′ portions linger in the cytoplasm for many hours. One explanation for the lingering of the 5′ domains is that the cleavage of truncated mRNA is blocked 5′ to 3′ and that the infected cells lack nucleases capable of degrading mRNA 3′ to 5′ (18–21).

(iv) Lastly, a series of studies shed light on the interaction of VHS-RNase with viral mRNA. In contrast to the results of cell-free studies, it was shown that VHS RNase is effective in degrading mRNAs made before infection but not the viral mRNAs made after infection (22). A key determinant of the fate of RNAs made after infection is a tegument protein encoded by the UL47 open reading frame (ORF) (23). The UL47 protein binds VHS and colocalizes with the VHS at the cap structure. Extensive degradation of viral mRNAs in cells infected with a mutant lacking the UL47 open reading frame supports the hypothesis that UL47 protein selectively blocks the degradation of viral and presumably host mRNAs made after infection but that it does not spare AU-rich mRNAs from degradation (22, 23).

The key issue addressed in current studies is the mechanism by which HSV discriminates between AU-rich mRNAs and RNAs devoid of AU-rich sequences. In earlier studies, this laboratory showed that the cleavage of AU-rich mRNAs takes place in the 3′ UTR in immediate proximity of the AU-rich elements (19). These studies also showed that VHS binds to TTP and advanced the hypothesis that VHS cleaves the AU-rich mRNAs by binding to TTP at the AU-rich sequence (24). The objective of the studies reported here was to test this hypothesis. In essence, mapping studies have enabled us to show that a single amino acid substitution in TTP that retained the ability of TTP to bind to VHS but disabled its ability to bind RNA blocked the degradation of AU-rich mRNAs in infected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

HEK-293T cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The limited-passage HSV-1(F) strain is the prototype HSV-1 strain used in this laboratory (25).

Antibodies.

Mouse polyclonal antibodies against Myc (Santa Cruz) or Flag (Sigma) were used at a dilution of 1:1,000. Goat polyclonal antibody against TTP (Sigma) and mouse monoclonal antibody against α-tubulin (Sigma) were used at dilutions of 1:500 and 1:1,000, respectively.

Transient transfection and infection.

HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected as previously reported (26). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were exposed to 5 PFU/cell of HSV-1(F) virus for 3 h before being incubated with medium containing actinomycin D (Act.D) (10 μg/ml; Sigma). Total RNA was extracted at the time of addition of Act.D (time zero) and the time points indicated in Fig. 6.

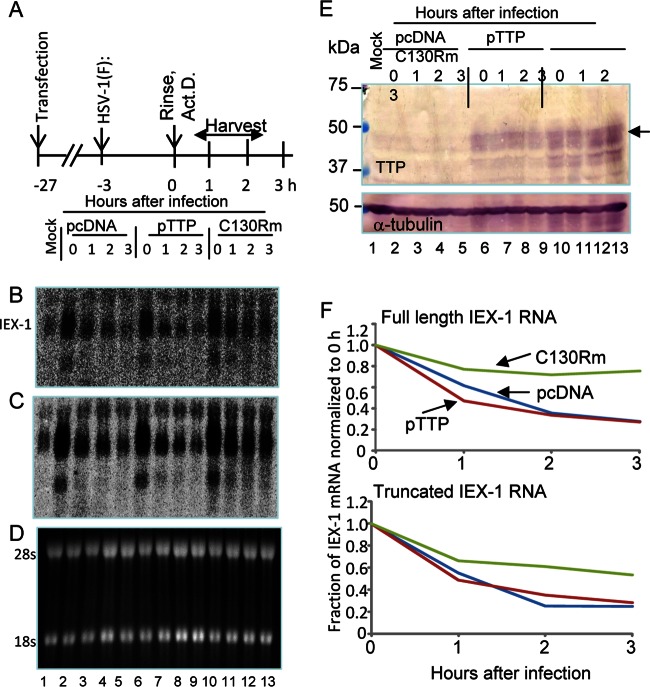

FIG 6.

The TTP C130R mutant selectively interferes with the degradation of IEX-1 mRNA by VHS RNase. (A) Diagram of experimental design. HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h, followed by exposure to 5 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 3 h. The inoculum was then replaced with fresh 199V medium. Transcription was then stopped by addition of 10 μg of Act.D per ml (time zero). Cells were harvested at the indicated time points. (B and C) Northern blot analysis of full-length and truncated IEX-1 mRNAs. Panels B and C represent shorter and longer exposures of the resolved IEX-1 RNAs, respectively. (D) Image of 18S and 28S RNAs resolved in the same blot. (E) The transiently expressed mutant and wild-type TTP proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-TTP antibody. The arrow points to full-length TTP. (F) Scan of the full-length and truncated IEX-1 mRNAs normalized to time zero.

Plasmid construction.

Plasmid construction was reported previously (27). Briefly, the mutant TTP ORF with C130R and mutant UL41 ORF with D398A, D402A, E408A, E411A, H412A, R413A, and K416A were obtained by use of the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The wild-type TTP(1–332) and truncated TTP(1–172), TTP(1–152), TTP(1–134), and TTP(1–114) fragments were obtained by PCR using the following primers: TTP(1–332)-N-Flag-forward, CCCAAGCTTATGGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGGCCAACCGTTACACCATGGATCTG; TTP(1–332)-reverse, CCGGAATTCTCACTCAGAAACAGAGATGCGATTGAAG; TTP(1–172)-reverse, CCGGAATTCTCAGTGGATGAAGTGGCAGCGAGAG; TTP(1–152)-reverse, CCGGAATTCTCAGAGTTCCGTCTTGTATTTGGGGTG; TTP(1–134)-reverse, CCGGAATTCTCAATGGGCAAACTGGCACTTGGCCCCGTAG; and TTP(1–114)-reverse, CCGGAATTCTCATAGCTCAGTCTTGTAGCGCGAG. The wild-type and mutant TTP ORFs tagged with Myc or Flag at the N terminus were subcloned in the multiple cloning site of pcDNA3.1(+).

RNase A treatment.

HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of pN-Flag-TTP plasmid. Cells were collected 48 h after transfection. Soluble cell extracts were incubated with RNase A (10 μg/ml) at room temperature (25°C) for 1 h. Efficiency of RNase A treatment was detected by loading of 20-μl protein samples incubated with or without RNase A on a 1% agarose gel stained by ethidium bromide.

GST pulldown assay.

The procedures were performed as previously described (27). Briefly, HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with the desired plasmids for 48 h. Cells were lysed in glutathione S-transferase (GST) lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 200 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and protease inhibitor mixture [complete protease mixture; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN]) on ice for 1 h. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation at maximum speed in a 5415C centrifuge (Eppendorf, Boulder, CO) for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant fluids precleared with 50 μl of a 50% slurry of glutathione beads for 3 h at 4°C were incubated overnight at 4°C with equal amounts of a 50% slurry of glutathione beads bound to GST alone or GST fused to VHS-WT(1–489), VHS(300–360), VHS(360–420), VHS(420–489), VHS(361–380), VHS(381–400), VHS(401–420), or mut-VHS(360–420). The beads were pelleted by centrifugation and rinsed five times with GST buffer (40 ml/time). The proteins bound to the beads were solubilized in 50 μl of SDS gel loading buffer (2% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 2.75% sucrose), heated to 95°C for 5 min, resolved by PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted with the mouse anti-Myc or anti-Flag antibodies.

Isolation of total RNA and Northern blot analyses.

Total RNA was extracted with the aid of TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNase (Life Technologies) treatment, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol (Fisher Scientific) precipitation were carried out to remove possible DNA contamination. The Northern blot analyses was done as described earlier (23), with minor modifications. Briefly, 15 μg of RNA was loaded onto a denaturing formaldehyde gel and probed with a random hexanucleotide-primed 32P-labeled fragment of IEX-1 upon transfer onto a nylon membrane. Prehybridization and hybridization were performed with ULTRAhyb buffer (Ambion, Austin, TX) supplemented with 200 μg of denatured salmon sperm DNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) per milliliter. The membrane was prehybridized for 2 h at 42°C and then overnight after the addition of the 32P-labeled probe. The membrane was rinsed as suggested by the manufacturer of the ULTRAhyb buffer and exposed to film for signal detection immunoblot analyses. HEK-293T cells were collected at the desired time points after infection. The procedures for harvesting, solubilization, protein quantification, SDS-PAGE, and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes were performed as previously reported (28). The membrane was probed for TTP and α-tubulin with the antibodies listed above.

RESULTS

Mapping of the minimal domain of VHS that interacts with TTP.

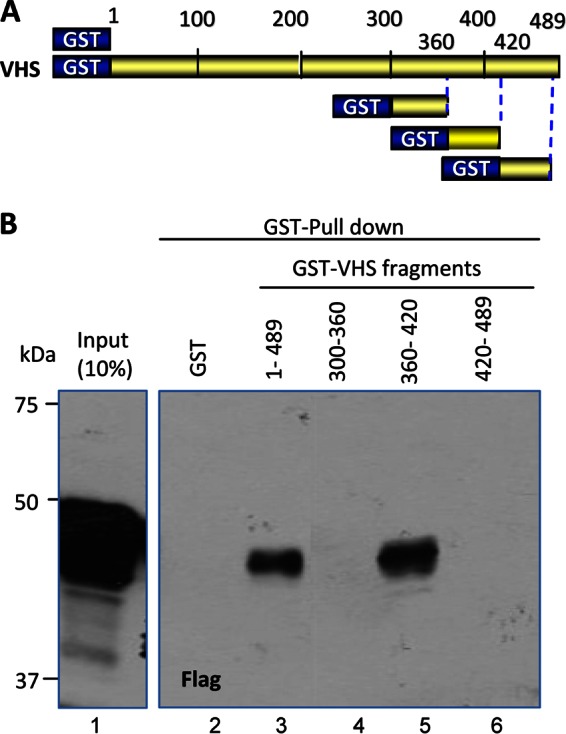

The basis of these studies is an earlier report showing that antibody to VHS pulled down TTP from lysates of wild-type virus-infected cells. Preliminary experiments established that TTP interacts with the C-terminal half of VHS. To map the binding site, we constructed a series of chimeric proteins consisting of GST fused to portions of the C-terminal domain of VHS (Fig. 1A). In the studies reported here, the chimeric proteins were reacted with a Flag-tagged TTP. As expected on the basis of earlier data, GST fused to intact VHS pulled down TTP (Fig. 1B, lane 3). Of the chimeric GST–C-terminal fragments, only GST fused to residues 360 to 420 pulled down TTP (Fig. 1B, lane 5). GST alone was ineffective (Fig. 1B, lane 2).

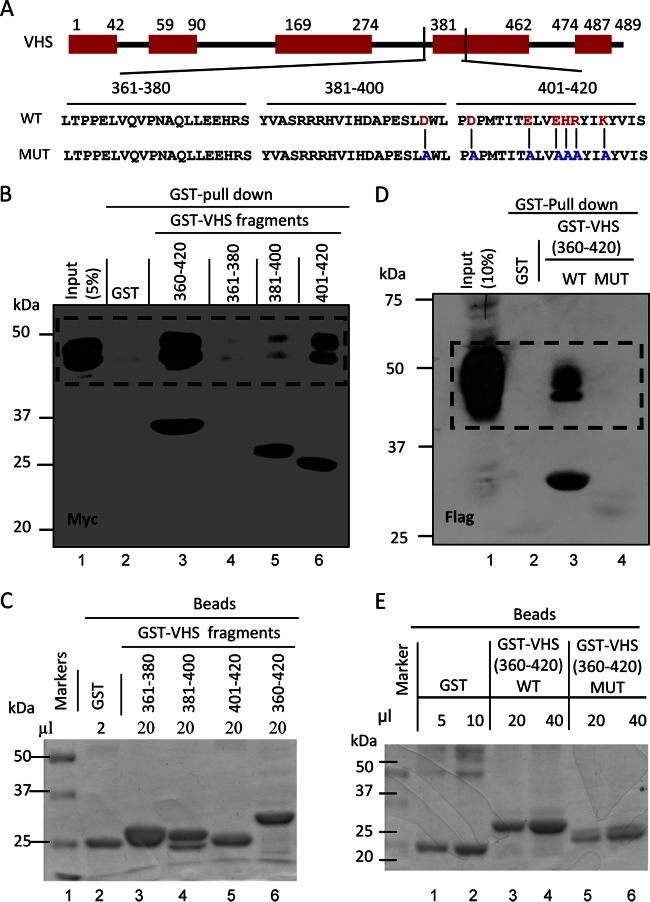

FIG 1.

Mapping of the VHS domain that binds to TTP. (A) Schematic diagram of full-length VHS and VHS fragments used in GST pulldown experiment in panel B. (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with pN-Flag-TTP plasmid encoding full-length TTP tagged with Flag at the N terminus. Soluble cell extracts prepared 48 h after transfection were reacted with glutathione-agarose beads bound to GST (lane 2) or GST fusions with full-length VHS (residues 1 to 489) (lane 3) or VHS residues 300 to 360 (lane 4), 60 to 420 (lane 5), or 420 to 489 (lane 6). The proteins bound to the beads were solubilized, subjected to electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and reacted with antibody against Flag. Immunoreactivity of full-length TTP from a 1/10th volume of whole-cell lysate is also shown (lane 1).

To narrow down the binding site, we constructed a new series of chimeric fragments consisting of GST fused to residues 361 to 380, 381 to 400, or 401 to 420. In pulldown experiments, TTP was pulled down by both chimeric proteins containing VHS residues 381 to 400 and 401 to 420, respectively (Fig. 2B). The input controls are shown in Fig. 2C and E. To fine map the interacting site, we focused on the VHS domains that are conserved among alphaherpesviruses, shown as red blocks in Fig. 2A. Within the conserved domain we replaced 7 codons (for residues D398, D402, E408, EHR411 to -413, and K416, shown in red) with codons specifying alanines. In contrast to the chimeric fragment containing the wild-type residues 361 to 420 (Fig. 2D, lane 3), the chimeric fragment containing alanines in place of the 7 mostly charged amino acids did not pull down TTP (Fig. 2D, lane 4). The input controls are shown in Fig. 2E.

FIG 2.

Mapping of the minimal domain of VHS that interacts with TTP. (A) Schematic diagram of full-length VHS and VHS fragments used in GST pulldown experiments shown in panels B and D. The VHS amino acids whose substitutions abolished binding to TTP are also shown in red. The red blocks indicate the VHS domains conserved among members of the alphaherpesviruses. (B) Pulldown of TTP by GST-VHS fragments. HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with full-length TTP tagged with Myc at the N terminus (pN-Myc-TTP). Soluble cell extracts were prepared 48 h after transfection and reacted with 4 μl of glutathione-agarose beads bound to GST (lanes 2) or 20 μl of GST-VHS(360–420) (lane 3), 10 μl of GST-VHS(361–380) (lane 4), 20 μl of GST-VHS(381–400) (lane 5), and 20 μl of GST-VHS(401–420) (lane 6). The pN-myc-TTP proteins bound to the beads were solubilized, subjected to electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and reacted with antibody against Myc. Immunoreactivity of full-length TTP (lane 1) from a 1/20th volume of whole-cell lysates is also shown. Note that the amounts of beads in the reaction mixtures were determined on the basis of GST-VHS proteins bound to the beads and shown in panel C. This panel shows the amounts of GST-VHS proteins solubilized from the beads subjected to electrophoresis in a denaturing gel and stained with Coomassie blue. (D) HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with pN-Flag-TTP plasmid encoding full-length TTP tagged with Flag at the N terminus. Soluble cell extracts were prepared 48 h after transfection and reacted with 10 μl of glutathione-agarose beads bound to GST (lanes 2) or 20 μl of GST–WT-VHS (360–420) (lane 3), or 40 μl of GST-VHS(360–420) (lane 4). In the GST-VHS(360–420) fragment, the 7 mostly charged residues shown in panel A were replaced with alanines. The proteins bound to the beads were subjected to electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and reacted with antibody against Flag. Immunoreactivity of full-length TTP (lane 1) from a 1/10th volume of whole-cell lysates is also shown. The amount of beads reacted with the GST-VHS(360–420) was determined from the amounts of protein bound to the beads. Specifically, the proteins bound to the beads were solubilized and subjected to electrophoresis in a denaturing gel and stained with Coomassie blue (E).

The RNA binding domain of TTP is required for the interaction of TTP with VHS.

To map the site of binding of TTP to VHS, we generated TTP plasmids containing either Flag-tagged full-length TTP (residues 1 to 332), the N-terminal domain (residues 1 to 172), or the N-terminal domain lacking the RNA binding sites (residues 1 to 114) (Fig. 3A). GST-tagged VHS residues 360 to 420 interacted strongly with the full-length TTP (Fig. 3B, lane 8) as well as with the N-terminal domain (Fig. 3B, lane 10). In contrast, we did not detect an interaction with the fragment lacking the RNA binding sites (Fig. 3B, lane 12).

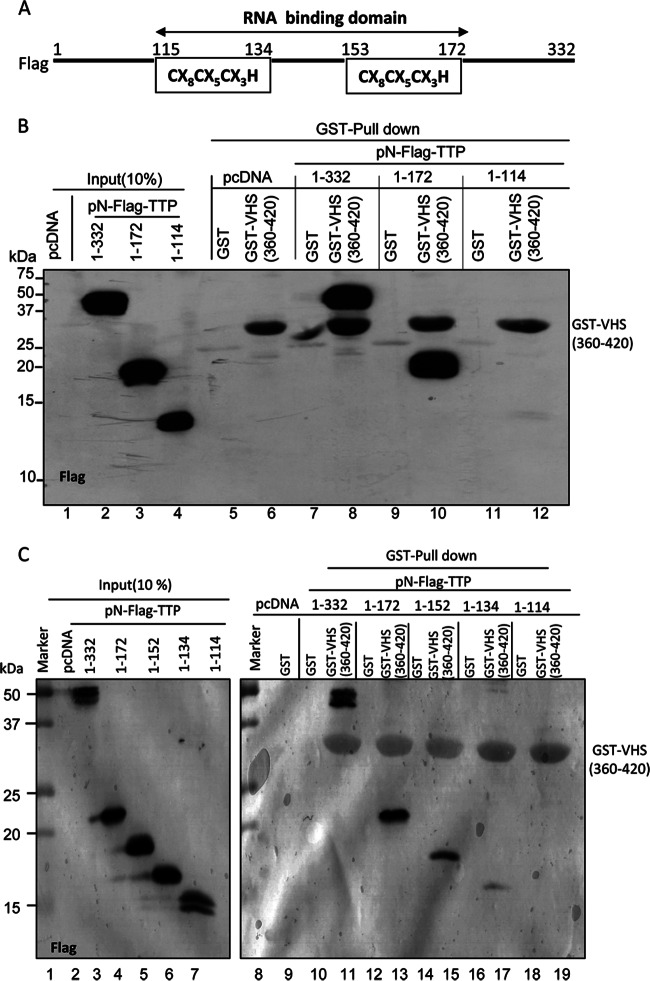

FIG 3.

Mapping of the minimal domain of TTP that interacts with VHS. (A) Schematic representation of TTP. The RNA binding domain (residues 115 to 172) of TTP contains two motifs of CX8CX5CX3H. (B and C) The RNA binding domain is required for the interaction of TTP and VHS. In panel B, HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids encoding pN-Flag-tagged full-length TTP (residues 1 to 332) or residues 1 to 172 or 1 to 114. In panel C, the HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding pN-Flag-tagged full-length TPP or residues 1 to 172, 1 to 152, 1 to 134, or 1 to 114. Soluble cell extracts were prepared 48 h after transfection and reacted with glutathione-agarose beads bound to GST (lanes 5, 7, 9, and 11 in panel B and lanes 9, 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18 in panel C) or GST-VHS(360–420) (lanes 6, 8, 10, and 12 in panel B and lanes 11, 13, 15, 17, and 19 in panel C). The proteins bound to the beads were solubilized and subjected to electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and reacted with antibody against Flag. Immunoreactivities of intact TTP and of the truncated portions of TTP are shown in lanes 2, 3, and 4 in panel B and lanes 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 of panel C. The amounts loaded in each lane represent 10% (vol/vol) of the whole-cell lysates. pcDNA, pcDNA 3.1(+).

To fine map the interacting domain, we constructed additional tagged plasmids. Specifically, the TTP contains two zinc finger (CCCH) motifs between residues 114 and 172. Figure 3C shows that the interaction of VHS and TTP decreased partially with the elimination of the second CCCH motif (residues 1 to 152 or 1 to 134 [lane 15 or 17]) and completely with the deletion of both CCCH motifs (residues 1 to 114 [lane 19]).

We conclude from these studies that domains of TTP interacting with VHS and those binding to RNA overlap.

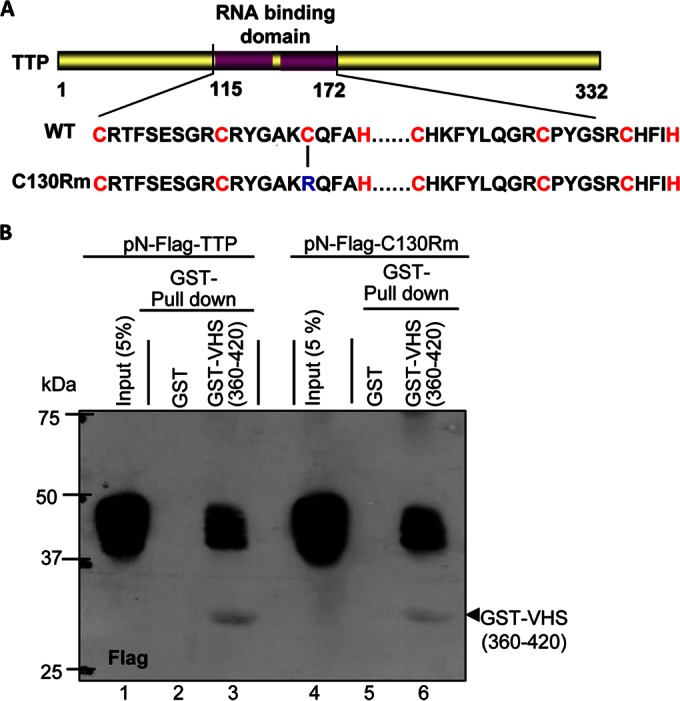

Interaction of TTP and VHS is independent of bound RNA or of integrity of the AU-rich RNA binding site in TTP.

We report two series of experiments. The first series of experiments was designed to determine whether the integrity of the RNA binding domain of TTP was required for the interaction with VHS. Studies done elsewhere indicated that the binding of TTP to the AU-rich elements in mRNAs is dependent on the integrity of both zinc finger motifs (CCCH). Thus, the substitution of a single cysteine with arginine in either zinc finger was reported to severely attenuate the binding of TTP to AU-rich elements (29, 30). To determine whether the interaction of VHS and TTP is dependent on binding of TTP to RNA, we substituted in the wild-type TTP C130 with arginine (Fig. 4A). HEK-293T cells were first transfected with 1 μg of plasmids encoding wild-type TTP or mutant TTP (C130R). As shown in Fig. 4B, the GST-VHS(360–420) chimeric protein pulled down both wild-type and mutant TTP from lysates of HEK-293T cells prepared 48 h after transfection.

FIG 4.

TTP carrying the mutation C130R binds to VHS. (A) Schematic representation of full-length TTP showing the positions of the two CCCH domains and the position of the C130R substitution. (B) HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids encoding pN-Flag-tagged TTP or the C130R mutant protein. Soluble cell extracts were prepared 48 h after transfection and reacted with glutathione-agarose beads bound to GST (lanes 2 and 5) or GST-VHS(360–420) (lanes 3 and 6). The proteins bound to the beads were subjected to electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and reacted with antibody against Flag. Immunoreactivity of wild-type TTP (lane 1) or mutant TTP (C130R) from a 1/20th volume of whole-cell lysates is also shown.

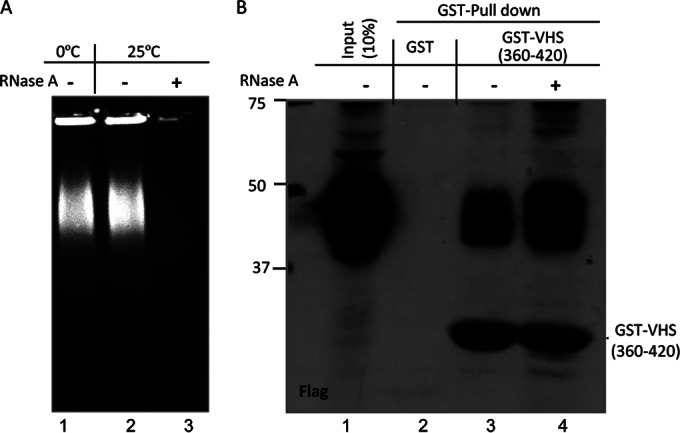

The second series of experiments addressed the question of whether RNA served as an intermediary in the binding of TTP and VHS. In these experiments, lysates of HEK-293T cells collected 48 h after transfection of a plasmid encoding TTP were incubated with RNase A for 1 h at room temperature. The RNase A-treated and mock-treated lysates (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 and 3) were reacted with a chimeric protein consisting of GST fused to the VHS(360–420) fragment. As shown in Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 4, RNA was not required for the interaction of TTP and VHS.

FIG 5.

The interaction of TTP and VHS does not depend on the presence of RNA. (A) HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of pN-Flag-TTP plasmid. Soluble cell extracts prepared 48 h after transfection were treated with RNase A (10 μg/ml) at room temperature (25°C) for 1 h. Twenty-microliter quantities of mock-treated (lane 2) or RNase A-treated (lane 3) protein samples were loading on a 1% agarose gel stained by ethidium bromide. Twenty microliters of protein sample kept on ice (lane 1) without RNase A treatment is also shown. (B) GST pulldown assay shows that RNase A treatment did not affect the interaction of TTP with VHS. Soluble cell extracts with or without RNase A treatment were prepared 48 h after transfection as mentioned above and reacted with glutathione-agarose beads bound to GST (lanes 2) or GST-VHS(360–420) (lane 3 and 4). The proteins bound to the beads were subjected to electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and reacted with antibody against Flag. Immunoreactivity of wild-type TTP (lane 1) from a 1/10th volume of whole-cell lysates is also shown.

In infected cells transiently expressing mutant or wild-type TTP, the TTP C130R mutant selectively interfered with the degradation of IEX-1 mRNA by VHS RNase.

To further investigate the role of TTP in the degradation of AU-rich mRNA by VHS RNase, HEK-293T cells were first transfected with pcDNA or plasmids encoding wide-type TTP or the TTP C130R mutant (C130Rm). After 24 h, the transfected cells were mock infected or exposed to 5 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 3 h. The inocula were then replaced with fresh medium containing Act.D. The cells were harvested at 0, 1, 2, or 3 h after exposure to the Act.D (Fig. 6A) and analyzed for the presence of transiently expressed mutant or wild-type TTP (Fig. 6B, lanes 6 to 13) and also for IEX-1 RNAs. Specifically, total RNAs were extracted, resolved in Northern blots, and hybridized to the IEX-1 RNA probe as previously described (23). The amounts of both full-length and truncated IEX-1 mRNA detected by hybridization are shown as short (Fig. 6B) and long (Fig. 6C) exposures. The fractions of IEX-1 mRNA present in the samples collected during the Act.D chase are shown in Fig. 6F. The results indicate that the TTP C130R mutant selectively interfered with the degradation of IEX-1 mRNA by VHS RNase. We conclude that the degradation of AU-rich mRNAs by VHS RNase is mediated by TTP.

DISCUSSION

The accrued results of numerous studies carried out in the past decade have shown that in cells infected with wild-type HSV-1, VHS selectively targets the AU-rich mRNAs. These mRNAs are made in copious amounts as a result of stress induced by changes in the environment of the cells. In uninfected cells in which the stress is transient, the consequences are activation of resident proteins (e.g., TIA-1) or induction of synthesis of proteins (e.g., TTP) that sequester and ultimately enable the degradation of the AU-rich RNAs. In brief, the activated or induced proteins sequester the AU-rich mRNAs in exosomes or P bodies and degrade them (15–17). The role of the AU-rich mRNAs in inducing a sturdy resistance to infection is clearly evident from studies of virus mutants lacking a functional VHS (18). The focus on TTP as a possible intermediary in the degradation of AU-rich mRNAs started from the observations that (i) AU-rich mRNAs are cleaved at or near the AU elements, (ii) VHS does not degrade TTP mRNA, and (iii) VHS and TTP interact (9, 18, 24). Here we report two key sets of experiments. Foremost, we mapped the sites of interaction of VHS with TTP and that of TTP with VHS. The key observation is that the TTP binding site for VHS RNase coincides with the binding site for RNA. Next, we showed that substitution in TTP of one residue known to abolish binding of TTP to RNA does not affect the binding of TTP to VHS. In the second set of experiments, we showed that transfection of cells with a plasmid encoding the mutant TTP precluded the degradation of AU-rich mRNAs following infection with wild-type virus. The results fully support the hypothesis that TTP acts as a ligand to bring VHS in contact with the 3′ UTRs of the AU-rich mRNAs.

The studies reported here enable us to begin to develop a comprehensive picture of the RNase function of VHS. It is summarized as follows.

VHS is brought into the cell during infection and is immediately transported to the nucleus either independently or bound to the UL47 protein (28, 31, 32).

To degrade non-AU-rich mRNAs, VHS must shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm. VHS contains a nuclear export signal and does not require the UL47 protein to shuttle from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. It requires UL47 to shuttle from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (28).

Two lines of evidence suggest that VHS degrades stable mRNAs in the cytoplasm. Foremost, mRNA degradation was demonstrated in polyribosomes (28, 33). In addition, the VHS mutant lacking the nuclear export signal accumulates in the nucleus. In this compartment the mutant VHS degrades AU-rich mRNAs but not stable mRNAs (23, 28). The data suggest that the mechanisms for degradation of stable and the short-lived AU-rich mRNAs are different.

As mentioned in the introduction, VHS RNase binds to the cap structure of mRNA. In the absence of the UL47 protein, VHS cleaves the mRNA at the cap structure and the CAP-less mRNA is degraded 5′ to 3′. There is no evidence to suggest that VHS or both VHS and the UL47 protein bind to stable mRNAs and not to AU-rich mRNAs. Rather, the data indicate that the AU-rich mRNAs are deadenylated and cleaved at the AU-rich elements in 3′ UTR. These observations are consistent with two cleavage events, one at the poly(A) sequence and one in the proximity of the AU-rich elements. Hence, VHS RNase and perhaps both VHS RNase and the UL47 protein may be present at the cap structure of the AU-rich elements.

Lastly, excessive VHS activity may be detrimental to HSV-1. As noted repeatedly over the years, the RNase activity is neutralized with the onset of synthesis of late proteins by VP16 and VP22 tegument proteins (27).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These studies were aided by National Cancer Institute grant CA115662.

We thank Lindsay Smith for his technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roizman B, Knipe DM, Whitley RJ. 2013. Herpes simplex viruses, p 1823–1897. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Lippincott-Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sydiskis RJ, Roizman B. 1966. Polysomes and protein synthesis in cells infected with a DNA virus. Science 153:76–78. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3731.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sydiskis RJ, Roizman B. 1967. The disaggregation of host polyribosomes in productive and abortive infection with herpes simplex virus. Virology 32:678–686. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Read GS, Frenkel N. 1983. Herpes simplex virus mutants defective in the virion-associated shutoff of host polypeptide synthesis and exhibiting abnormal synthesis of alpha (immediate early) viral polypeptides. J Virol 46:498–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwong AD, Frenkel N. 1987. Herpes simplex virus-infected cells contain a function (s) that destabilizes both host and viral mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84:1926–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strom T, Frenkel N. 1987. Effects of herpes simplex virus on mRNA stability. J Virol 61:2198–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwong AD, Frenkel N. 1989. The herpes simplex virus virion host shutoff function. J Virol 63:4834–4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taddeo B, Roizman B. 2006. The virion host shutoff protein (UL41) of herpes simplex virus 1 is an endoribonuclease with a substrate specificity similar to that of RNase A. J Virol 80:9341–9345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01008-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esclatine A, Taddeo B, Roizman B. 2004. The UL41 protein of herpes simplex virus mediates selective stabilization or degradation of cellular mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:18165–18170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408272102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page HG, Read GS. 2010. The virion host shutoff endonuclease (UL41) of herpes simplex virus interacts with the cellular cap-binding complex eIF4F. J Virol 84:6886–6890. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00166-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng P, Everly DN Jr., Read GS. 2005. mRNA decay during herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections: protein-protein interactions involving the HSV virion host shutoff protein and translation factors eIF4H and eIF4A. J Virol 79:9651–9664. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9651-9664.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elgadi MM, Hayes CE, Smiley JR. 1999. The herpes simplex virus vhs protein induces endoribonucleolytic cleavage of target RNAs in cell extracts. J Virol 73:7153–7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez-Parada J, Saffran HA, Smiley JR. 2004. RNA degradation induced by the herpes simplex virus vhs protein proceeds 5′ to 3′ in vitro. J Virol 78:13391–13394. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13391-13394.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bevilacqua A, Ceriani MC, Capaccioli S, Nicolin A. 2003. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression by degradation of messenger RNAs. J Cell Physiol 195:356–372. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CY, Gherzi R, Ong SE, Chan EL, Raijmakers R, Pruijn GJ, Stoecklin G, Moroni C, Mann M, Karin M. 2001. AU binding proteins recruit the exosome to degrade ARE-containing mRNAs. Cell 107:451–464. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoecklin G, Mayo T, Anderson P. 2006. ARE-mRNA degradation requires the 5′-3′ decay pathway. EMBO Rep 7:72–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin WJ, Duffy A, Chen CY. 2007. Localization of AU-rich element-containing mRNA in cytoplasmic granules containing exosome subunits. J Biol Chem 282:19958–19968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esclatine A, Taddeo B, Evans L, Roizman B. 2004. The herpes simplex virus 1 UL41 gene-dependent destabilization of cellular RNAs is selective and may be sequence-specific. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:3603–3608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400354101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taddeo B, Esclatine A, Zhang W, Roizman B. 2003. The stress-inducible immediate-early responsive gene IEX-1 is activated in cells infected with herpes simplex virus 1, but several viral mechanisms, including 3′ degradation of its RNA, preclude expression of the gene. J Virol 77:6178–6187. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6178-6187.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu WL, Saffran HA, Smiley JR. 2005. Herpes simplex virus infection stabilizes cellular IEX-1 mRNA. J Virol 79:4090–4098. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4090-4098.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corcoran JA, Hsu WL, Smiley JR. 2006. Herpes simplex virus ICP27 is required for virus-induced stabilization of the ARE-containing IEX-1 mRNA encoded by the human IER3 gene. J Virol 80:9720–9729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01216-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taddeo B, Zhang W, Roizman B. 2013. The herpes simplex virus host shutoff RNase degrades cellular and viral mRNAs made before infection but not viral mRNA made after infection. J Virol 87:4516–4522. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00005-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shu M, Taddeo B, Zhang W, Roizman B. 2013. Selective degradation of mRNAs by the HSV host shutoff RNase is regulated by the UL47 tegument protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E1669–E1675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305475110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esclatine A, Taddeo B, Roizman B. 2004. Herpes simplex virus 1 induces cytoplasmic accumulation of TIA-1/TIAR and both synthesis and cytoplasmic accumulation of tristetraprolin, two cellular proteins that bind and destabilize AU-rich RNAs. J Virol 78:8582–8592. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8582-8592.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ejercito PM, Kieff ED, Roizman B. 1968. Characterization of herpes simplex virus strains differing in their effects on social behaviour of infected cells. J Gen Virol 2:357–364. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-2-3-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taddeo B, Zhang W, Roizman B. 2010. Role of herpes simplex virus ICP27 in the degradation of mRNA by virion host shutoff RNase. J Virol 84:10182–10190. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00975-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taddeo B, Sciortino MT, Zhang W, Roizman B. 2007. Interaction of herpes simplex virus RNase with VP16 and VP22 is required for the accumulation of the protein but not for accumulation of mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:12163–12168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705245104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shu M, Taddeo B, Roizman B. 2013. The nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of virion host shutoff RNase is enabled by pUL47 and an embedded nuclear export signal and defines the sites of degradation of AU-rich and stable cellular mRNAs. J Virol 87:13569–13578. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02603-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai WS, Carballo E, Strum JR, Kennington EA, Phillips RS, Blackshear PJ. 1999. Evidence that tristetraprolin binds to AU-rich elements and promotes the deadenylation and destabilization of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA. Mol Cell Biol 19:4311–4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai WS, Carballo E, Thorn JM, Kennington EA, Blackshear PJ. 2000. Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA. Binding of tristetraprolin-related zinc finger proteins to AU-rich elements and destabilization of mRNA. J Biol Chem 275:17827–17837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yedowitz JC, Kotsakis A, Schlegel EF, Blaho JA. 2005. Nuclear localizations of the herpes simplex virus type 1 tegument proteins VP13/14, vhs, and VP16 precede VP22-dependent microtubule reorganization and VP22 nuclear import. J Virol 79:4730–4743. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4730-4743.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taddeo B, Zhang W, Roizman B. 2006. The U(L)41 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 degrades RNA by endonucleolytic cleavage in absence of other cellular or viral proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:2827–2832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510712103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taddeo B, Zhang W, Roizman B. 2009. The virion-packaged endoribonuclease of herpes simplex virus 1 cleaves mRNA in polyribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:12139–12144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905828106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]