Abstract

Background: Many patients with advanced cancer at our hospital request full resuscitative efforts at the end of life. We assessed the knowledge and attitudes of these patients towards end-of-life (EOL) care, and their preferences about “Do Not Resuscitate” (DNR), “Allow Natural Death” (AND), and “full code” orders.

Methods: The first 100 consenting adult patients with advanced cancer were surveyed regarding their diagnosis, prognosis, and attitudes about critical care and resuscitation. They were then presented with hypothetical scenarios in which a decision on their code status had to be made if they had one year, six months, or one month left to live. Half were given a choice between being “full code“ and “DNR,” and half could choose between ”full code” and “AND.”

Results: All 93 of the participants who completed the survey were considered by their attending physician to have a terminal illness, but only 42% of these interviewees believed they were terminally ill. In addition, only 25% of participants thought that their primary oncologist knew their EOL wishes. Participants were equally likely to choose either of the “no code” options in all hypothetical scenarios (p>0.54), regardless of age, sex, race, type of cancer, education, or income level. A similar proportion of patients who had a living will chose “AND” and “DNR” orders instead of “full code” in all the scenarios (47%–74% and 63%–71%). In contrast, among patients who did not have a living will, 52% chose “DNR,” while 19% opted for “AND.”

Conclusions: We hypothesized that “AND” orders may be more acceptable to patients with advanced cancer, but there was no statistically significant difference in acceptability between “AND” and “DNR” orders.

Introduction

On admission to acute care hospitals, patients or their surrogate decision makers must be asked if the patient has advance directives (ADs). In addition, the admitting provider may inquire which life-prolonging measures, if any, should be performed in case of active or impending cardiorespiratory arrest. In medical jargon, allowing all such measures is considered “full code,” while an order not to perform any such procedures is called a “Do Not Resuscitate” (DNR) order. These discussions are often conducted between a patient with a serious illness and a clinician who has never met them before. The dialogue may be open and frank, yet lack a broader perspective on the patient's life, their illness, and their goals. If a patient's medical condition worsens, a more pressing decision about actual end-of-life (EOL) care may follow.

It has been proposed that using the “softer, more comforting, warmer” term “Allow Natural Death” (AND) instead of DNR may be more acceptable to patients and families considering EOL issues.1 The phrase “AND” was first introduced at the St. David's Medical Center in Austin, Texas, with the hope that it would “increase the number of terminally ill patients who were allowed a death with dignity.”2 In subsequent studies with neutral participants and surrogate decision makers—but not patients themselves—examinees were more likely to choose an AND than a DNR order.3,4 Unfortunately, there is paucity of information about terminally ill cancer patients' acceptance of “AND” and “DNR” orders, about their knowledge of EOL treatment options, and about which factors contribute to the decisions they make regarding EOL care. This is a study of how patients with advanced cancer perceive their own prognosis and EOL care in general. In addition, their preferences towards being full code versus either “DNR” or “AND” were explored and analyzed in relation to patients' characteristics, attitudes, and perceived prognosis.

Methods

Patients were invited to participate in the survey if their attending oncologist indicated they had advanced cancer and a projected life expectancy of less than one year, and they met the following criteria: (1) had capacity to make their own health care decisions, (2) spoke English as their first language, (3) were older than 18 years of age, (4) agreed to participate, and (5) their physician agreed that they could be approached for consent. After verbal agreement from the attending physician for the patient to participate, interviewers approached the patient and obtained informed consent. The information gathered was not shared with the patients' health care providers, though patients were encouraged to discuss these issues with them. A total of 112 patients were asked to participate and 100 agreed (89%). Seven of the 100 patients did not complete the interview. Two reported feeling uncomfortable with the topics that were being discussed, and five needed to be taken for additional testing, treatment, or for an unanticipated admission.

Upon approval of the institutional review board (IRB), a research associate or a resident physician in internal medicine not directly involved in patient care conducted semistructured interviews with 100 patients with advanced cancer who were seen at the outpatient cancer center or were admitted to the hematology-oncology inpatient service in a community hospital. Responses were recorded by the interviewer and entered into an IRB-approved database.

After obtaining demographic data and inquiring about the patients' past medical history and current cancer stage, including whether they believed they had a terminal illness, they were asked about their general knowledge and attitude regarding life support and resuscitation orders (see Table 1). At the end of the interview participants were given three hypothetical scenarios in which their projected life expectancies were one year, six months, and one month. Patients were randomly assigned to either be presented with the option of being “full code” or “DNR,” or “full code” and “AND.” A sample size of 100 was planned to allow for the ability to determine a 20% difference in response rate to this portion of the study. Standard descriptive statistics were used as appropriate. Paired t-test and chi square test were used for testing statistical significance of parametric and nonparametric variables respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| “AND” group (n=46) | “DNR” group (n=47) | Total (n=93) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 64 (29–88) | 62 (31–88) | 62 (29–88) |

| Men (%) | 15 (32.6) | 15 (31.9) | 30 (32.3) |

| Caucasian (%) | 29 (63.0) | 26 (55.3) | 55 (59.1) |

| College degree or higher (%) | 13 (28.3) | 13 (27.7) | 26 (28.0) |

| Income | |||

| <20,000 USD/year | 11 (23.9) | 8 (17.0) | 19 (20.4) |

| 21,000–50,000 USD/year | 13 (28.3) | 11 (23.4) | 24 (25.8) |

| >50,000 USD/year | 11 (23.9) | 13 (27.7) | 24 (25.8) |

| Cancer type | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 11 (23.9) | 15 (31.9) | 26 (30.0) |

| Genitourinary | 13 (28.3) | 9 (19.1) | 22 (23.7) |

| Hematological | 8 (17.4) | 5 (10.6) | 13 (14.0) |

| Breast | 6 (13.0) | 6 (12.8) | 12 (12.9) |

| Lung | 5 (10.9) | 7 (14.9) | 12 (12.9) |

| Sarcoma | 4 (8.7) | 2 (4.3) | 6 (6.4) |

| Glioblastoma | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (3.2) |

| Other | 2 (4.3) | 2 (4.3) | 4 (4.3) |

| One or more comorbidities (%) | 23 (50.0) | 16 (34.0) | 39 (41.9) |

Results

Of the 93 patients who completed the entire interview, 47 received the “DNR” and 46 the “AND” word choice in the hypothetical scenarios. The groups were similar in gender, ethnicity, education and income levels, cancer type, number of comorbidities, religion, and spirituality (see Table 1). Despite the two groups being similar demographically and in their reported knowledge of life-sustaining interventions, their attitudes towards those interventions were not the same (see Table 2). More patients in the “AND” than in the “DNR” group wanted to be maintained on a ventilator, have a tracheostomy and feeding tube placed, and receive CPR if they were to be in a permanent vegetative state (p values 0.009–0.038). Patients in both groups were more agreeable to CPR than any other life-prolonging measure.

Table 2.

Participants' Knowledge and Beliefs about EOL Care and Life-Prolonging Measures

| “AND” group % (n=46) | “DNR” group % (n=47) | Total % (n=93) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Believes they have a terminal illness | 15 (32.6) | 24 (51.1) | 39 (41.9) |

| Has a living will | 21 (45.6) | 25 (53.2) | 46 (49.5) |

| Has DPOA | 18 (39.1) | 18 (38.3) | 36 (38.7) |

| Knows about: | |||

| ventilators | 37 (80.4) | 37 (78.7) | 74 (79.6) |

| intubation | 39 (84.8) | 40 (85.1) | 79 (84.9) |

| tracheostomy | 41 (89.1) | 43 (91.5) | 84 (90.3) |

| feeding tubes | 46 (100) | 45 (95.7) | 91 (97.8) |

| CPR | 46 (100) | 47 (100) | 93 (100) |

| If permanently unconscious, would want: | |||

| to be on a ventilator | 18 (39.1) | 7 (14.9) | 25 (26.9) |

| to have a tracheostomy placed | 20 (43.4) | 10 (21.3) | 30 (32.3) |

| to have a feeding tube placed | 22 (47.8) | 10 (21.3) | 32 (34.4) |

| to have CPR performed on me | 27 (58.7) | 17 (36.2) | 43 (46.2) |

| Doctor knows these wishes | 13 (28.3) | 10 (21.3) | 23 (24.7) |

| DPOA/someone close knows these wishes | 36 (78.3) | 33 (70.2) | 69 (74.2) |

DPOA, durable power of attorney for healthcare.

The patients' knowledge and beliefs about life-prolonging measures are shown in Table 2. Of note, all of the participants were considered by their attending physicians to have a terminal illness, but only 42% of interviewees believed they had one. In addition, just 25% of participants thought that their primary oncologist knew their EOL wishes. Of the 64 interviewees who had not made their wishes known to their primary oncologist, 36 (56%) did not want to discuss life support wishes with them in the future.

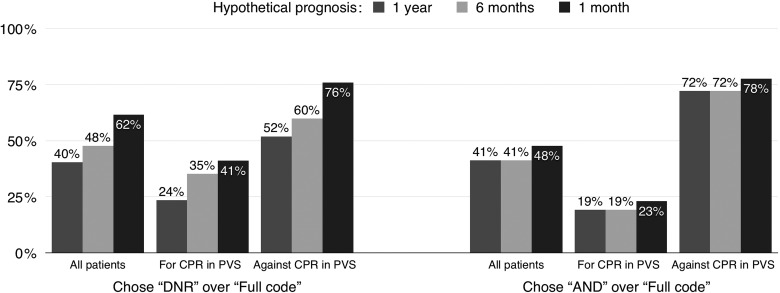

Participants were equally likely to choose either of the “no code” options in all hypothetical scenarios (p values>0.54; see Fig. 1). Choosing “DNR” and “AND” was not correlated with any of the demographic characteristics presented in Table 1 (p values>0.05). The proportion of patients who chose “DNR” or “AND” increased as their hypothetical survival time shortened.

FIG. 1.

End-of-life choices in three different scenarios of patients presented with “DNR” and “full code” orders, and patients presented with “AND” and “full code” orders, overall and by different CPR preferences. AND, allow natural death; DNR, dot not resuscitate; PVS, permanent vegetative state.

As could be expected, patients who were in favor of CPR, intubation, tracheostomy, or feeding tube placement in case of a permanent vegetative state were significantly less likely to choose “AND” or “DNR” versus “full code” in any of the scenarios (p values<0.001; see Fig. 1). For patients who were against having CPR, the proportion choosing “DNR” (when given the option of “DNR” or “full code”) grew as the hypothetical prognosis worsened. In contrast, for those who were opposed to having CPR and were given the choice between “AND” and “full code,” the proportion choosing “AND” was already high when one year survival was projected, and did not increase significantly as projected life expectancy was shorter (p values 0.003–0.031; see Fig. 1). Of patients who reported not having a living will, 45% chose the “DNR” order but only 8% chose “AND” when these options were offered along with being “full code” (p values<0.001).

Discussion

In this study of patients with advanced cancer, 58% of participants did not believe that their condition was terminal, 50% did not have a living will, and 61% had not appointed a health care power of attorney. Nearly all participants self-reported having knowledge about CPR, intubation, and other life-prolonging measures; but the minority of participants had a living will (LW) (49%) or durable power of attorney for healthcare (DPOA) (39%), similarly to previous reports.5,6 Seventy-five percent of patients reported that the oncologist did not know their EOL wishes, which was consistent with previous studies.7,8 Interestingly, 56% of the patients in this study whose oncologists did not know their EOL wishes did not wish to discuss this topic with the clinician.

Previous studies with health care providers and patients' family members indicated that “AND” phrasing might be more acceptable than “DNR.”3,9 In our sample of 93 patients with advanced cancer, however, there was no statistically significant difference in acceptability between “AND” and “DNR,” even as the clinical scenario predicted shorter survivals, to even one month of life (AND acceptance 47.83% versus DNR acceptance 61.70% at one month of predicted survival; see Fig. 1).

Since the interviewees' emotional response and comfort with the two discussions was not evaluated and compared, we cannot know their effect on what participants chose in each scenario. Another limitation of the study is that, despite randomization being successful in terms of demographic characteristics (see Table 1), significantly more patients in the “AND” group were in favor of CPR beforehand; and fewer had living wills, making the number of patients that chose the “no code” order in each group harder to compare.

Proponents of “AND” phrasing cite emotional comfort as one of its advantages when compared to “DNR.”8,9 We hypothesized that “AND” would be more acceptable than “DNR,” but overall the two orders were equally acceptable. For a subset of patients who were given a projected life expectancy of one year and indicated that they would not want CPR, the “DNR” order was more acceptable than “AND.” Instead of using different phrasing to affect the patients' choices, providers could use other methods to educate patients about EOL care—including video decision support tools11,12 or palliative care consult teams.13,14

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Cohen RW: A tale of two conversations. Hastings Cent Rep 2004;34:49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer C: “Allow Natural Death An Alternative to DNR?” Hospice Patients Alliance Website. 2014. www.hospicepatients.org/and.html (Last accessed December10, 2013)

- 3.Venneman SS, Narnor-Harris P, Perish M, et al. : “Allow natural death” versus “do not resuscitate:” Three words that can change a life. J Med Ethics 2008;34:2–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnato AE, Arnold RM: The effect of emotion and physician communication behaviors on surrogates' life-sustaining treatment decisions: A randomized simulation experiment. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1686–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo Y, Palmer JL, Bianty J, et al. : Advance directives and do-not-resuscitate orders in patients with cancer with metastatic spinal cord compression: Advanced care planning implications. J Palliat Med 2010;13:513–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma RK, Dy SM: Documentation of information and care planning for patients with advanced cancer: Associations with patient characteristics and utilization of hospital care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2011;28:543–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virmani J, Schneiderman LJ, Kaplan RM: Relationship of advance directives to physician-patient communication. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:909–913 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamont EB, Siegler M: Paradoxes in cancer patients' advance care planning. J Palliat Med 2000;3:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones BL, Parker-Raley J, Higgerson R, et al. : Finding the right words: Using the terms allow natural death (AND) and do not resuscitate (DNR) in pediatric palliative care. J Healthc Qual 2008;30:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley CG, Lipson AR, Daly BJ, et al. : Advance directive use and psychosocial characteristics: An analysis of patients enrolled in a psychosocial cancer registry. Cancer Nurs 2009;32:335–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:380–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein AS, Volandes AE, Chen LY, et al. : A randomized controlled trial of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation video in advance care planning for progressive pancreas and hepatobiliary cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2013;16:623–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonsalves WI, Tashi T, Krishnamurthy J, et al. : Effect of palliative care services on the aggressiveness of end-of-life care in the Veteran's Affairs cancer population. J Palliat Med 2011; 14:1231–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacco J, Deravin Carr DR, Viola D: The effects of the Palliative Medicine Consultation on the DNR status of African Americans in a safety-net hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013;30:363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]