Abstract

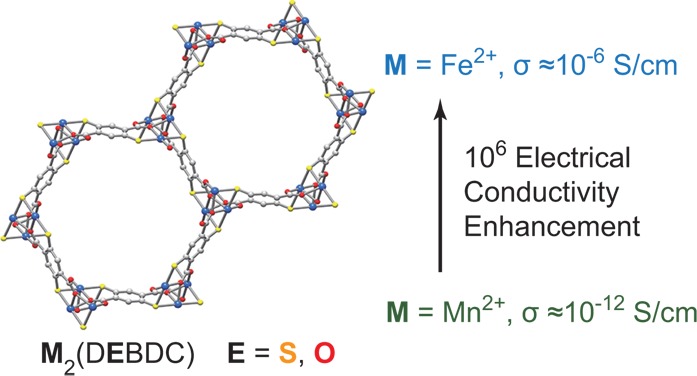

Reaction of FeCl2 and H4DSBDC (2,5-disulfhydrylbenzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid) leads to the formation of Fe2(DSBDC), an analogue of M2(DOBDC) (MOF-74, DOBDC4– = 2,5-dihydroxybenzene-1,4-dicarboxylate). The bulk electrical conductivity values of both Fe2(DSBDC) and Fe2(DOBDC) are ∼6 orders of magnitude higher than those of the Mn2+ analogues, Mn2(DEBDC) (E = O, S). Because the metals are of the same formal oxidation state, the increase in conductivity is attributed to the loosely bound Fe2+ β-spin electron. These results provide important insight for the rational design of conductive metal–organic frameworks, highlighting in particular the advantages of iron for synthesizing such materials.

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) that display intrinsic electrical conductivity are still rare, but conductivity is emerging as an attractive complement to the inherent porosity of these materials. If high surface area is combined with electrical conductivity or high charge mobility, MOFs could find uses in fields outside traditional areas such as gas storage and separation, and make strides into batteries,1 supercapacitors,2 electrocatalysis,3 and sensing,4 among others. Although recent reports of conductive MOFs have crystallized several potential avenues toward improved electrical properties, including in-plane π-conjugation,4,5 through-space charge transport,6 through-bond charge transport,7 and doping,7d,8 these design strategies require significant refinement.

In this context, we recently reported Mn2(DSBDC), a MOF-74 analogue that contains (-Mn-S-)∞ chains, and discussed the positive effect of replacing phenoxide by thiophenoxide groups on charge mobility.7a While this was inspired by the rich literature of organic conductors, where heavier chalcogens generally lead to better electrical properties,9 the equally compelling literature of inorganic semiconductors shows, for instance, that iron chalcogenides10 are better intrinsic conductors than manganese chalcogenides,11 highlighting that the metal ions may be as important as the chalcogens. Taking a cue from inorganic chalcogenides, we wanted to test the relative importance of the metal ion for MOFs with infinite chains as their secondary building units. To do so, we set out to compare the Mn2+ and Fe2+ analogues of the family of materials known as MOF-74, surmising that replacement of Mn2+ by Fe2+ would lead to superior electrical conductivity, as seen for the inorganic chalcogenides. Here, we show that within isostructural materials, replacing Mn2+ with Fe2+ leads to a million-fold enhancement in electrical conductivity, a considerably more pronounced effect than substituting bridging O atoms with less electronegative S atoms.

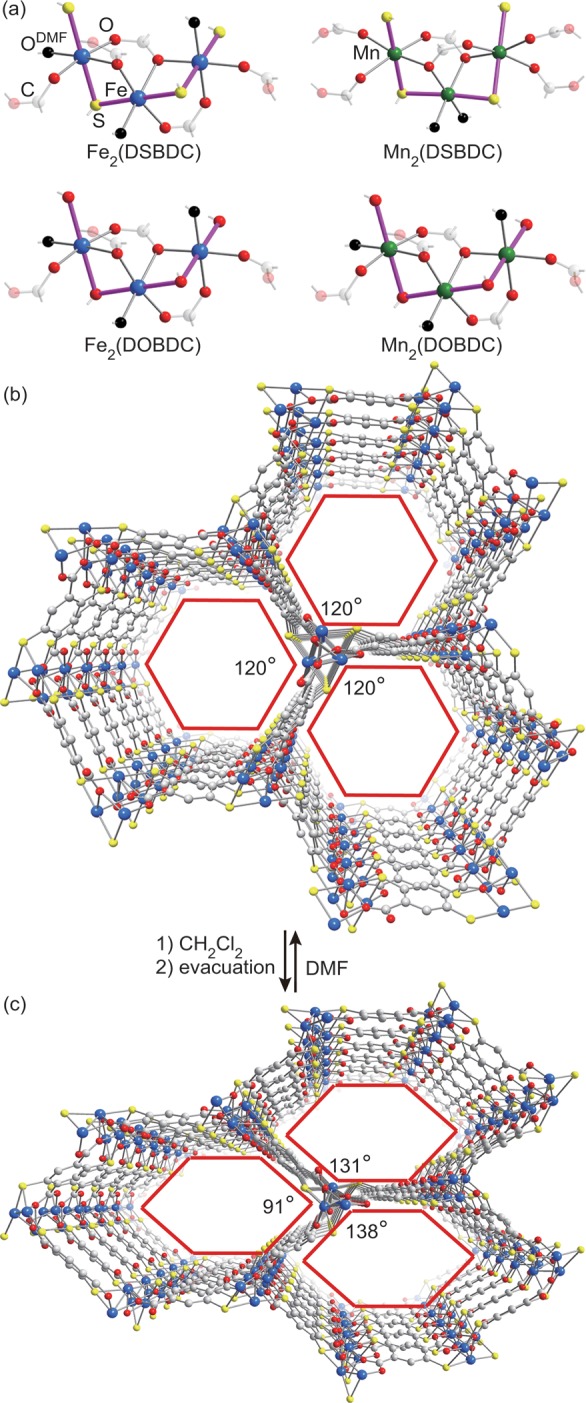

[Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2]·x(DMF) was isolated as dark red-purple crystals after heating a degassed and dry solution of H4DSBDC and anhydrous FeCl2 in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) at 140 °C under an N2 atmosphere for 24 h, and washing with additional DMF. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)·x(DMF) revealed an asymmetric unit containing one Fe atom coordinated by three carboxylate groups, two thiophenoxide groups, and one DMF molecule. The sulfur atoms are coordinated in trans fashion to the Fe2+ atom, with Fe–S bond lengths of 2.444(2) and 2.446(2) Å. This indicates that both S atoms interact with the same d orbital of Fe2+, an important orbital symmetry requirement for efficient charge transport.12 Although Fe2(DSBDC) is isostructural with Fe2(DOBDC)13 and Mn2(DOBDC),14 its structure is only topologically related to that of Mn2(DSBDC). As shown in Figure 1a, whereas Fe2(DSBDC) has a single metal atom in the asymmetric unit, Mn2(DSBDC) has two: one that is octahedrally coordinated by donors on DSBDC4– ligands, and another that is bound by two DMF molecules. Relevantly, the two distinct metal ions in Mn2(DSBDC) reduce the symmetry of the (-Mn-S-)∞ chains, which may negatively affect its charge transport properties. As in other MOF-74 analogues, the (-Fe-S-)∞ chains in Fe2(DSBDC) are bridged by thiophenoxide and carboxylate groups to form a three-dimensional framework with one-dimensional hexagonal pores with a van der Waals diameter of ∼16 Å (Figures 1b and S1).

Figure 1.

(a) Parts of the infinite secondary building units in M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) (M = Fe, Mn; E = S, O). The (-M-E-)∞ chains are represented in purple. (b,c) Partial structures of Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) and Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2 as determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction and DFT structure optimization, respectively. H atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity.

When M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) are soaked in dichloromethane and then evacuated under vacuum (100 °C, 2 h), they yield M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2, a series of materials that are guest-free and where DMF completes the coordination sphere of all metal sites. Infrared spectroscopy and microelemental analysis confirmed that all guest solvent molecules were removed under these conditions (Figure S4). Surprisingly, powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) revealed that Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2 is distorted in comparison to Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF), a distortion that was not observed in the other three analogues (Figures S3 and S5). Mathematical simulation and DFT optimization of completely solvent-free Fe2(DSBDC)15 gave a structure whose simulated pattern agreed well with the observed PXRD pattern of Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2 (see Figure 1c and the Supporting Information). This distortion is reversible: soaking Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2 in fresh DMF produced a crystalline phase with a PXRD pattern identical to that of Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) (Figure S6). To our knowledge, although breathing behavior has been observed for several classes of MOFs,16 it has never been associated with MOF-74 analogues.

N2 sorption analysis revealed Brunauer–Emmet–Teller (BET) surface areas of 232, 241, and 287 m2/g for Mn2(DSBDC)(DMF)2, Fe2(DOBDC)(DMF)2, and Mn2(DOBDC)(DMF)2, respectively, confirming their guest-free nature and permanent porosity (Figure S8). These values are lower than those expected for completely activated MOF-74 analogues because coordinated DMF molecules occupy a significant portion of the pore volume in M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2. Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2 exhibited a lower BET surface area of 54 m2/g, likely because the distorted pores in this case are almost entirely occupied by coordinated DMF molecules (Figure S9).

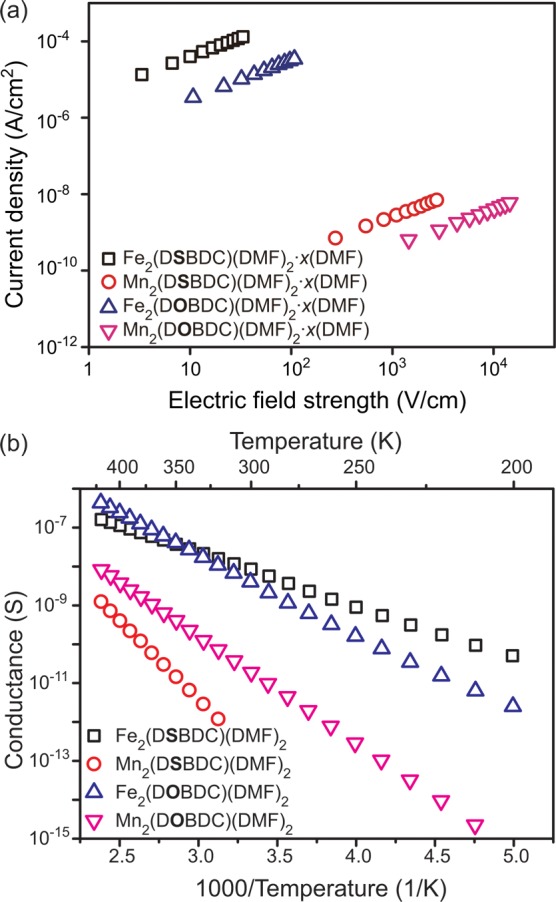

Owing to the small crystallite size of all of these materials, single-crystal measurements of their electrical properties proved unfeasible. Accordingly, we prepared pellets of both M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) and M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2 materials, for a total of eight samples, all of which were analyzed by two-probe current–voltage techniques. Plots of measured current density versus electric field strength, shown for the as-synthesized samples in Figure 2a and for the guest-free samples in Figure S10, revealed striking differences in electrical conductivity between the Fe and Mn analogues, regardless of their solvation level. Indeed, both Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) (σ = 3.9 × 10–6 S/cm) and Fe2(DOBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) (σ = 3.2 × 10–7 S/cm) were ∼6 orders of magnitude more conductive than Mn2(DSBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) and Mn2(DOBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF), which exhibited conductivities of 2.5 × 10–12 and 3.9 × 10–13 S/cm, respectively (Table 1).17 Although the guest-free materials showed slightly lower conductivities overall, possibly due to additional defects and grain boundaries caused by the solvent exchange and guest removal process, they reflected the same remarkable 6 orders of magnitude difference in conductivity between the Fe and Mn analogues (Table 1). Although at the lower end of intrinsically conductive and porous MOFs, whose conductivity ranges between 10–6 and 102 S/cm,4−7 the conductivity of the Fe frameworks described here is the highest in the MOF-74 family and is comparable to that of typical organic conductors (>10–6 S/cm).18

Figure 2.

Electrical properties of M2(DEBDC) (M = Fe, Mn; E = S, O) pressed pellets. (a) Plots of current density versus electric field strength (J–E curves) for M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) at 297 K. (b) Conductance–temperature relationship for M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2.

Table 1. Electrical Properties of M2(DEBDC) (M = Fe, Mn; E = S, O).

| Fe2(DSBDC) | Mn2(DSBDC) | Fe2(DOBDC) | Mn2(DOBDC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σas-synthesized (S/cm)a | 3.9 × 10–6 | 2.5 × 10–12 | 3.2 × 10–7 | 3.9 × 10–13 |

| σguest-free (S/cm)b | 5.8 × 10–7 | 1.2 × 10–12 | 4.8 × 10–8 | 3.0 × 10–13 |

| Ea (eV)c | 0.27 | 0.81 | 0.41 | 0.55 |

| Eg (eV)d | 1.92 | 2.60 | 1.47 | 2.48 |

| Φ (eV)e | 3.71 | 3.81 | 2.81 | 3.72 |

Electrical conductivity of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF) at 297 K.

Electrical conductivity of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2 at 297 K.

Activation energy of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2.

Calculated bandgap of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2.

Calculated work function of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2.

To probe the cause of the large difference between the Fe and Mn analogues, we determined the activation energy in M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2 by measuring their pellet conductance under variable temperature between 200 and 420 K. Working with guest-free rather than as-synthesized materials was necessary because our variable-temperature, air-free electrical microprobe setup requires that samples be passed through an evacuation chamber. However, it is reasonable to assume that because neutral guest solvent molecules are unlikely to contribute to charge transport, the activation energies of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2 are not vastly different and follow the same trends as those of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2·x(DMF). All samples showed an increase in conductance with increasing temperature, indicative of semiconducting behavior (see Figure 2b). Fitting the respective conductance values, G, to the Arrhenius law (eq 1) revealed notable differences in activation energies, Ea, shown in Table 1. Thus, both Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2 (Ea = 0.27 eV) and Fe2(DOBDC)(DMF)2 (Ea = 0.41 eV) had considerably lower activation energies than Mn2(DSBDC)(DMF)2 (Ea = 0.81 eV) and Mn2(DOBDC)(DMF)2 (Ea = 0.55 eV), suggesting that the Fe-based MOFs have smaller band gaps and hence higher charge density than the Mn-based MOFs.

| 1 |

Notably, the addition of a single electron per metal ion (i.e., substitution of d5 Mn2+ for d6 Fe2+) has a much more pronounced positive effect on conductivity than changing the bridging atom from O to S, indicating that the electronic structure of the metal ions plays the most important role in charge conduction in this class of materials. To confirm the oxidation state and high-spin configuration of the Fe atoms, we measured 57Fe Mössbauer spectra of both Fe-based MOFs. As shown in Figures S11 and S12, these spectra revealed well-resolved doublets characterized by isomer shifts of 1.172 and 1.308 mm/s, and quadrupole splittings of 3.218 and 2.739 mm/s, for Fe2(DSBDC) and Fe2(DOBDC), respectively. Because the isomer shifts of both MOFs fall in the expected range of high-spin Fe2+, these experiments demonstrated that oxidation to Fe3+ did not occur during our experiments.

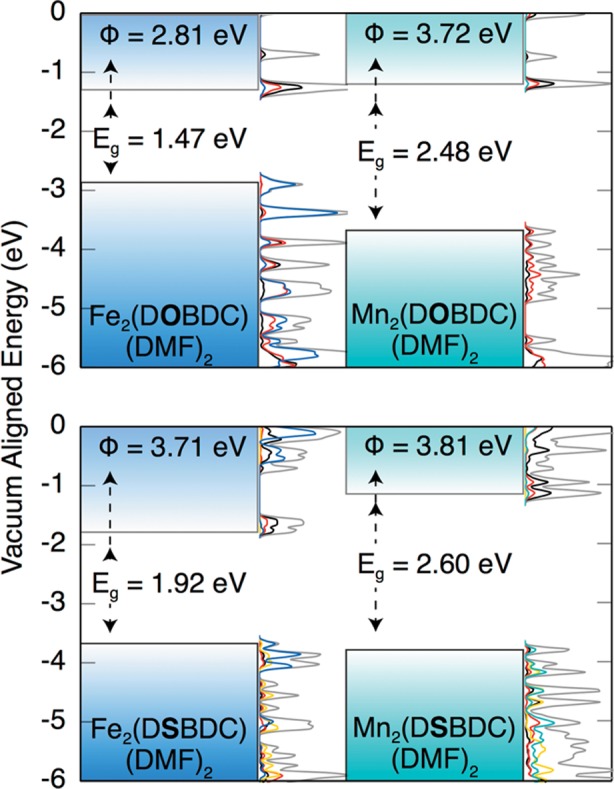

Density functional calculations were used to further probe the differences in electronic structure of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2, and the significance of the additional d electron associated with the Fe2+ ions. The electronic density of states and ionization potentials of the guest-free system are presented in Figure 3, and detailed in the Supporting Information. Because Fe2(DOBDC) and Mn2(DOBDC) are structurally analogous, while Fe2(DSBDC) and Mn2(DSBDC) differ in the number of metal ions in their asymmetric units, the comparison between Fe2(DOBDC) and Mn2(DOBDC) illustrates best the difference between Mn2+ and Fe2+. Most importantly, the valence band maximum of Mn2(DOBDC) is composed of C-p, O-p, and Mn-d states, while in Fe2(DOBDC) the Fe-d states dominate the valence band, with negligible contribution from ligand orbitals. This difference is attributed to the low binding energy of the filled β-spin d band of Fe2+, which is empty for the d5 high-spin Mn2+ ions.20 Furthermore, because the lower conduction band in both MOFs is dominated by ligand-based orbitals, the band gaps are narrowed owing to a decreased work function. As a result, the calculated work functions and band gaps of Fe2(DOBDC) are 0.91 and 1.01 eV smaller than those of Mn2(DOBDC), respectively.

Figure 3.

Calculated energy bands and projected density of states (DOS) of M2(DEBDC)(DMF)2 (M = Fe, Mn; E = S, O). The work function, Φ, and the absolute energy scale are aligned to vacuum according to ref (19). Gray curves represent total DOS. Blue, teal, yellow, red, and black curves represent projected DOS of Fe, Mn, S, O, and C, respectively.

To assess the relative importance of the chalcogen atom on the charge transport, we also compared the structurally analogous Fe2(DSBDC) and Fe2(DOBDC) materials. First, the valence and conduction bands of these frameworks are flat in reciprocal space (dispersion of <100 meV in all cases). This behavior is indicative of localized orbitals rather than delocalized bands, and is typical of many MOFs.21 Thus, we anticipate that the primary mode of conduction is through charge hopping. Moreover, because the Fe2+ d orbitals dominate the valence band (83% of the orbital contribution), intervalence transitions between Fe atoms will proceed with little contribution from O. In contrast, due to the enhanced orbital overlap in Fe2(DSBDC), where Fe and S orbitals contribute 53% and 14% to the valence band, transport will occur through both Fe and S in the (-Fe-S-)∞ chains. This mechanism lowers the charge hopping barrier and is also associated with the larger work function of Fe2(DSBDC) compared with that of Fe2(DOBDC). Finally, the increased contribution of C-p states to the valence band in Fe2(DSBDC) compared to Fe2(DOBDC) may also indicate a more efficient interchain transport, which further increases the conductivity of the former.

In summary, the synthesis of a new MOF-74 analogue based on (-Fe-S-)∞ chains led to a material with the highest conductivity in the MOF-74 structural family. The combination of loosely bound Fe2+ β-spin electrons and the low electronegativity of S atoms contributes to the higher relative conductivity of Fe2(DSBDC). Applying similar design principles to other MOFs made from one-dimensional secondary building units should lead to further improvements in electrical properties for materials in this class.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under award no. DE-SC0006937. Part of the characterization was performed at the Shared Experimental Facilities, supported by the NSF under the MRSEC Program (DMR-08-19762). M.D. thanks the Sloan Foundation, the Research Corporation for Science Advancement, and 3M for non-tenured faculty awards. Work in the UK benefited from access to ARCHER through membership in the UK’s HPC Materials Chemistry Consortium, which is funded by EPSRC (Grant No. EP/L00202). Additional support was received from the European Research Council (Grant No. 277757). We thank Prof. S. J. Lippard for use of the Mössbauer spectrometer and Prof. J. R. Long for valuable discussions.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental details, table of X-ray refinement details, PXRD patterns, IR spectra, I–V curves, Mössbauer spectra, isotherms, computational details, and crystallographic data (CIF). The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b02897.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Férey G.; Millange F.; Morcrette M.; Serre C.; Doublet M.; Grenèche J.; Tarascon J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Demir-Cakan R.; Morcrette M.; Nouar F.; Davoisne C.; Devic T.; Gonbeau D.; Dominko R.; Serre C.; Férey G.; Tarascon J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 16154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wiers B. M.; Foo M.; Balsara N. P.; Long J. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhang Z.; Yoshikawa H.; Awaga K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. M.; Jeong H. M.; Park J. H.; Zhang Y.; Kang J. K.; Yaghi O. M. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 7451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nohra B.; Moll H. E.; Albelo M. R.; Mialane P.; Marrot J.; Mellot-Draznieks C.; O’Keeffe M.; Biboum R. N.; Lemaire J.; Keita B.; Nadjo L.; Dolbecq A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ahrenholtz S. R.; Epley C. C.; Morris A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. G.; Sheberla D.; Liu S.; Swager T. M.; Dincă M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hmadeh M.; Lu Z.; Liu Z.; Gándara F.; Furukawa H.; Wan S.; Augustyn V.; Chang R.; Liao L.; Zhou F.; Perre E.; Ozolins V.; Suenaga K.; Duan X.; Dunn B.; Yamamto Y.; Terasaki O.; Yaghi O. M. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 3511. [Google Scholar]; b Kambe T.; Sakamoto R.; Hoshiko K.; Takada K.; Miyachi M.; Ryu J.; Sasaki S.; Kim J.; Nakazato K.; Takata M.; Nishihara H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cui J.; Xu Z. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sheberla D.; Sun L.; Blood-Forsythe M. A.; Er S.; Wade C. R.; Brozek C. K.; Aspuru-Guzik A.; Dincă M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Narayan T. C.; Miyakai T.; Seki S.; Dincă M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Park S. S.; Hontz E. R.; Sun L.; Hendon C. H.; Walsh A.; Van Voorhis T.; Dincă M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Avendano C.; Zhang Z.; Ota A.; Zhao H.; Dunbar K. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhang Z.; Zhao H.; Kojima H.; Mori T.; Dunbar K. R. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sun L.; Miyakai T.; Seki S.; Dincă M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gándara F.; Uribe-Romo F. J.; Britt D. K.; Furukawa H.; Lei L.; Cheng R.; Duan X.; O’Keeffe M.; Yaghi O. M. Chem.—Eur. J. 2012, 18, 10595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Takaishi S.; Hosoda M.; Kajiwara T.; Miyasaka H.; Yamashita M.; Nakanishi Y.; Kitagawa Y.; Yamaguchi K.; Kobayashi A.; Kitagawa H. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 9048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kobayashi Y.; Jacobs B.; Allendorf M. D.; Long J. R. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 4120. [Google Scholar]

- a Zeng M.; Wang Q.; Tan Y.; Hu S.; Zhao H.; Long L.; Kurmoo M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Talin A. A.; Centrone A.; Ford A. C.; Foster M. E.; Stavila V.; Haney P.; Kinney R. A.; Szalai V.; Gabaly F. E.; Yoon H. P.; Léonard F.; Allendorf M. D. Science 2014, 343, 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday B. J.; Swager T. M. Chem. Commun. 2005, 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fu G.; Polity A.; Volbers N.; Meyer B. K.; Mogwitz B.; Janek J. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 262113. [Google Scholar]; b Park J.; Kim D.; Lee C.; Kim D. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 1999, 20, 1005. [Google Scholar]

- a Makovetskiǐ G. I.; Galyas A. I.; Demidenko O. F.; Yanushkevich K. I.; Ryabinkina L. I.; Romanova O. B. Phys. Solid State 2008, 50, 1826. [Google Scholar]; b Bhide V. G.; Dani R. H. Physica 1961, 27, 821. [Google Scholar]

- a Anderson P. W. Phys. Rev. 1950, 79, 350. [Google Scholar]; b Kanamori J. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1959, 10, 87. [Google Scholar]; c Tiana D.; Hendon C. H.; Walsh A. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 13990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bhattacharjee S.; Choi J.; Yang S.; Choi S. B.; Kim J.; Ahn W. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bloch E. D.; Murray L. J.; Queen W. L.; Chavan S.; Maximoff S. N.; Bigi J. P.; Krishna R.; Peterson V. K.; Grandjean F.; Long G. J.; Smit B.; Bordiga S.; Brown C. M.; Long J. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wu H.; Zhou W.; Yildirim T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cozzolino A. F.; Brozek C. K.; Palmer R. D.; Yano J.; Li M.; Dincă M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Optimizing Fe2(DSBDC)(DMF)2 itself was computationally unfeasible because the solvent molecules add 72 atoms to the unit cell.

- a Barthelet K.; Marrot J.; Riou D.; Férey G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Murdock C. R.; Hughes B. C.; Lu Z.; Jenkins D. M. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 258–259, 119. [Google Scholar]

- J–E curves and log scale are used in Figure 2a to show the difference among conductivities of various MOFs clearly. See Supporting Information.

- Saito G.; Yoshida Y. Top. Curr. Chem. 2012, 321, 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler K. T.; Hendon C. H.; Walsh A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Li B.; Chen L. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 9356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler K. T.; Hendon C. H.; Walsh A. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 22044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.