Abstract

Behcet disease (BD) is a chronic, multisystem, inflammatory disease characterized by variable clinical manifestations involving systemic vasculitis of both the small and large blood vessels. The majority of BD patients present with recurrent oral ulcers in combination with other manifestations of the disease, including genital ulcers, skin lesions, arthritis, uveitis, thrombophlebitis, gastrointestinal or central nervous system involvement. Gastrointestinal BD occurs in 3 to 25% of the BD patients and shares many clinical characteristics with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Consequently, the differentiation between IBD and gastrointestinal manifestation of BD is very difficult. Intestinal BD should be considered in patients who present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and rectal bleeding who are susceptible or at a risk for intestinal BD.

Keywords: Behcet disease, colitis, inflammatory bowel diseases

Behcet disease (BD) is a chronic, multisystem, inflammatory disease characterized by variable clinical manifestations involving systemic vasculitis of both the small and large blood vessels.1 The syndrome was first described by Turkish dermatologist Hulusi Behcet in 1937 as a syndrome of oral and genital ulcerations and ocular inflammation.2 The majority of BD patients present with recurrent oral ulcers in combination with other manifestations of the disease, including genital ulcers, skin lesions, arthritis, uveitis, thrombophlebitis, gastrointestinal or central nervous system involvement. Gastrointestinal BD occurs in 3 to 25% of the BD patients and shares many clinical characteristics with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).3 Consequently, the differentiation between IBD and gastrointestinal manifestation of BD is very difficult. Intestinal BD should be considered in patients who present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and rectal bleeding who are susceptible or at a risk for intestinal BD.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of BD varies by region.4 BD is more commonly seen in countries along the historic Silk Road from the Mediterranean to East Asia.5 It is greatest in Turkey with a reported 80 to 370 cases per 100,000 individuals. In contrast, the prevalence is only 1 to 2 cases per one million individuals in the United States.2 The clinical manifestations of the disease also vary by region. For example, gastrointestinal involvement is more frequent in those patients from the Far East, especially Japan.6 In the United States, approximately one-third of the BD patients have intestinal BD. Onset of the syndrome typically occurs in the third decade of life. Both genders are equally affected, but the syndrome tends to be more severe in males.7

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Genetic and environmental factors are believed to play a role in the development of BD. However, the underlying etiology is still unknown. The pathophysiology of Behcet syndrome includes excessive neutrophil response, vascular injury, and autoimmune responses.3 Numerous genetic variants have been associated with BD, the most common being HLA-B51.8

Clinical Presentation/Intestinal Manifestations

Symptoms of gastrointestinal involvement are similar to those associated with IBD. These include anorexia, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhea, GI bleeding, and abdominal pain.9 These symptoms are often the consequence of mucosal ulcerations. Mucosal ulceration is most commonly seen in the ileum, followed by the cecum and other parts of the colon.4 Mucosal ulceration in BD is thought to be secondary to a small vessel vasculitis, particularly of veins and venules, and large vessel involvement may sometimes occur and lead to ischemia and infarction.3

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of BD is difficult and based primarily on clinical findings. In 1990, the International Study Group (ISG) for BD established a set of diagnostic criteria (Table 1).10

Table 1. International study group criteria for Behcet disease.

| Recurrent oral ulceration plus two of the following |

|---|

| Recurrent genital ulceration |

| Eye lesions (retinitis or uveitis) |

| Skin lesions (erythema nodosum and/or papulopustular lesions) |

| Positive pathergy reaction |

Unfortunately, there is no pathognomonic test for BD and findings are typically nonspecific.11 Patients may have elevated serum markers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). In patients with active BD, serum immunoglobulin D (IgD), serum immunoglobulin A (IgA), and complement levels may be elevated as well. Antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor autoantibodies are typically absent.6

The pathergy test involves insertion of a sterile 20–22 gauge needle into the skin at three places on each forearm. A hypersensitivity reaction as shown by an erythematous papule, pustule or ulcer greater than 2 mm after 48 hours indicates a positive result. Despite being a component of the ISGBD diagnostic criteria, pathergy test results have limited reproducibility and vary by geography. In North America, only 5% of the population has a positive result. A positive result can also be seen in other diseases, such as IBD and pyoderma gangrenosum.12

Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) positivity can be found in up to 44% of the patients with intestinal BD, but only 3 to 4% of patients with nonintestinal BD and 9% of healthy control subjects. ASCA positivity is associated with increased rate of operative interventions.2 Alpha-enolase antibody has also been detected in patients with BD and may be associated with disease activity and severity.13

Imaging

Several imaging modalities can be used to assist the diagnosis of intestinal BD, including barium swallow, barium enema, or computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging (CT/MRI).14 CT and MRI scans are useful for demonstrating colonic wall thickening (Fig. 1) and evaluating extraluminal complications, such as abscesses or perforations. However, the radiographic findings are nonspecific to BD.2

Fig. 1.

Computerized tomographic scanning shows a complex inflammatory mass without abscess or perforation in the cecum of a patient with gastrointestinal Behcet disease.

Endoscopy

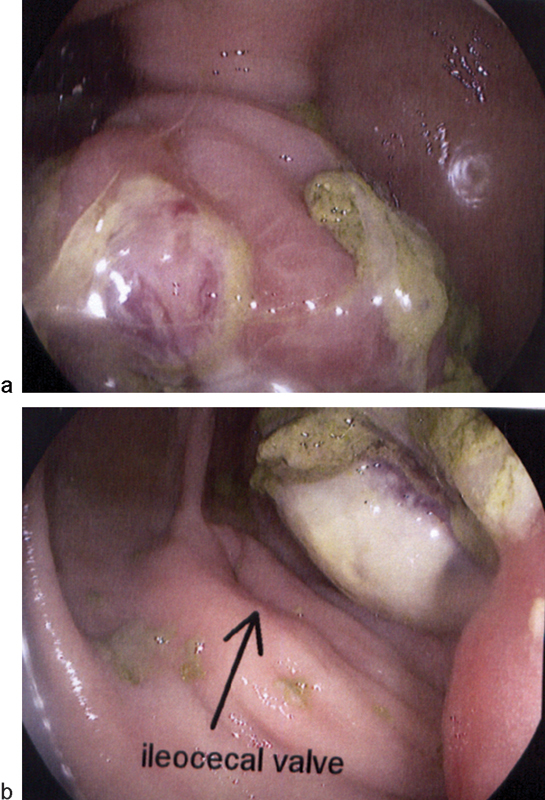

In BD, ulcers on colonoscopy are typically irregular, round or oval, punched-out, large (> 1 cm), single to a few in number, deep, and with discrete margins in a focal distribution (Fig. 2).15 The majority of patients with intestinal BD have lesions in the ileocecal region. Diffuse colonic involvement is rare and rectal and anal involvement is extremely rare. Colonic ulcers have also been described as volcano-type lesions because they are deeply penetrating and have nodular margins caused by fibrosis. These ulcers are less responsive to medical therapy and frequently require surgical resection (Fig. 3).2 Complications, such as fistula formation, hemorrhage, or perforation, occur in approximately 50% of the cases involving the intestine.16

Fig. 2.

Colonoscopy in a patient with gastrointestinal Behcet disease shows a mass with ischemic ulceration: (a) the ascending colon with (b) close proximity to the ileocecal valve.

Fig. 3.

Right colon and terminal ileum surgical specimen from a patient with gastrointestinal Behcet disease shows focal ulceration in the proximal ascending colon consistent with ischemic ulcer.

Differences in Clinical Manifestations between Intestinal Behcet Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Intestinal BD and Crohn disease (CD) have common presenting symptoms including diarrhea, abdominal pain, and gastrointestinal bleeding. However, there are subtle clues that favor the diagnosis of BD over CD (Table 2). As mentioned previously, endoscopic findings of ulcers in BD typically show irregular, round or oval, punched-out, large (> 1 cm), deep ulcers with discrete margins in a focal distribution. In contrast, CD typically has segmental, diffuse, longitudinal lesions, with cobblestone appearance.

Table 2. Comparison of Behcet disease and Crohn disease.

| Behcet disease | Crohn disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic findings | Focal distribution of disease Large ulcers (> 1 cm) Round or oval, punched out lesions Deep ulcers Ulcers with discrete margins < 6 ulcers |

Segmental disease Discontinuous involvement of various portions of the gastrointestinal tract Diffuse, longitudinal lesions Cobblestone appearance |

| Biopsy | Vasculitis | Granulomas |

| Location | Perianal disease rare | Perianal disease frequent |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | Genital lesions Papulopustular lesions Neurologic involvement |

Musculoskeletal, dermatologic, hepatopancreatobiliary, ocular, renal, and pulmonary systems |

Transmural enteritis or colitis can occur both in BD or CD. However, the finding of vasculitis on biopsy suggests intestinal BD.17 Fistula formation, intestinal perforation, and gastrointestinal bleeding can occur both in BD and CD.

Extraintestinal manifestations can be similar in BD and IBD. These include uveitis, arthritis, oral ulcers, pyoderma gangrenosum, and thrombophlebitis. However, there is an increased association of genital lesions, papulopustular lesions, and neurologic involvement in BD.2

Despite subtle differences, distinguishing between both, diagnosis may not be possible.

Management

Treatment of intestinal BD is similar to that for IBD, but with overall prognosis worse in intestinal BD. Treatment is dependent on clinical manifestation with priority given to ocular, intestinal, and central nervous system symptoms as well as large vessel vasculitis.

Medical Management

Medical treatment for gastrointestinal manifestations of BD is often identical to the therapies used for IBD.2 Sulfasalazine or mesalamine (5-ASA) and corticosteroids are the primary therapies used to treat intestinal BD. Corticosteroids are the first-line therapy during acute episodes of BD or in patients with severe systemic symptoms, recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding, or moderate/severe disease activity. Dosing is dependent on the severity of the lesions. However, many patients become corticosteroid resistant or dependent, and other medications, such as azathioprine and thalidomide, have been used to successfully reduce or stop corticosteroid use.

Infliximab (Remicade, Janssen Biotech Inc., Horsham, PA), a chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, has been found to be beneficial in patients unresponsive to conventional therapies and is often first-line therapy for sight-threatening uveitis. Infliximab is typically dosed according to the CD protocol as a standard treatment regimen has not been established in BD.

Intestinal BD has also been successfully treated with adalimumab (Humira, Abbott, AbbVie, Inc., North Chicago, IL), a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF-α.

Surgical Management

Indications for surgical intervention include severe gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, fistulae, obstructions, abdominal masses, and failure to respond to medical therapy.18 There is a high rate of intestinal leakage, perforation, and fistula formation at the anastomotic site.14 Consequently, creation of a stoma is preferred over primary anastomosis. Disease recurrence is seen in 40 to 80% of the patients and often occurs at or near the anastomotic site.19 Up to 80% of the patients require a repeat operation due to failure of medical therapy, perforation, or fistula formation.20 There remains controversy over the preferred surgical procedure and length of bowel resection.

Prognosis

Remission rates with medical therapy are similar to those achieved in CD.2 However, recurrence rates are higher in BD and patients more often require surgical intervention. Poor prognostic factors include volcano-shaped ulcers, higher CRP levels, history of postoperative corticosteroid therapy, presence of perforation on pathology, extensive ileal disease, presence of ocular disease, and positive ASCA status.18

Conclusion

It is often difficult to distinguish BD as they are two diseases which are often based on clinical judgment. The diagnosis of intestinal BD should be considered in patients who have a family history of BD or who present with symptoms associated with BD, such as oral ulcers, genital ulcers, and skin lesions.

References

- 1.Moutsopoulos H M Behcet's Syndrome New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grigg E L, Kane S, Katz S. Mimicry and deception in inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal Behçet disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2012;8(2):103–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sands B E. From symptom to diagnosis: clinical distinctions among various forms of intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(6):1518–1532. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yurdakul S, Tüzüner N, Yurdakul I, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H. Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's syndrome: a controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(3):208–210. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.3.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koutroubakis I E. Spectrum of non-inflammatory bowel disease and non-infectious colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(48):7277–7279. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yurdakul S, Yazici H. Behçet's syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(5):793–809. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yazici H, Tüzün Y, Pazarli H. et al. Influence of age of onset and patient's sex on the prevalence and severity of manifestations of Behçet's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984;43(6):783–789. doi: 10.1136/ard.43.6.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizuki N, Inoko H, Ohno S. Pathogenic gene responsible for the predisposition of Behçet's disease. Int Rev Immunol. 1997;14(1):33–48. doi: 10.3109/08830189709116843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oshima Y, Shimizu T, Yokohari R. et al. Clinical studies on Behçet's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1963;22(1):36–45. doi: 10.1136/ard.22.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Study Group for Behçet's Disease . Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet's disease. Lancet. 1990;335(8697):1078–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yazici H, Yazici Y. Criteria for Behçet's disease with reflections on all disease criteria. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatemi I Hatemi G Celik A F et al. Frequency of pathergy phenomenon and other features of Behçet's syndrome among patients with inflammatory bowel disease Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008; 26(4, Suppl 50):S91–S95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin S J, Kim B C, Kim T I, Lee S K, Lee K H, Kim W H. Anti-alpha-enolase antibody as a serologic marker and its correlation with disease severity in intestinal Behçet's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(3):812–818. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1326-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayraktar Y, Ozaslan E, Van Thiel D H. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behcet's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30(2):144–154. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J S, Lim S H, Choi I J. et al. Prediction of the clinical course of Behçet's colitis according to macroscopic classification by colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2000;32(8):635–640. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim E S, Chung W C, Lee K M. et al. A case of intestinal Behcet's disease similar to Crohn's colitis. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22(5):918–922. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.5.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sayek I, Aran O, Uzunalimoglu B, Hersek E. Intestinal Behçet's disease: surgical experience in seven cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38(1):81–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung Y S, Yoon J Y, Lee J H. et al. Prognostic factors and long-term clinical outcomes for surgical patients with intestinal Behcet's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(7):1594–1602. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon C M, Cheon J H, Shin J K. et al. Prediction of free bowel perforation in patients with intestinal Behçet's disease using clinical and colonoscopic findings. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(10):2904–2911. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(17):1284–1291. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]