Abstract

Introduction

Reading skills are critical for the success of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Literacy has received little attention in fragile X syndrome (FXS), the most common inherited cause of intellectual impairment. This study examined the literacy profile of FXS and tested phonological awareness and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) symptoms as predictors of literacy.

Methods

Boys with FXS (n = 51; mean age 10.2 years) and mental-age-matched boys with typical development (n = 35) participated in standardized assessments of reading and phonological skills.

Results

Phonological skills were impaired in FXS, while reading was on-par with that of controls. Phonological awareness predicted reading ability and ASD severity predicted poorer phonological abilities in FXS.

Conclusion

Boys with FXS are capable of attaining reading skills that are commensurate with developmental level and phonological awareness skills may play a critical role in reading achievement in FXS.

Keywords: fragile X syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, ASD, literacy, reading, phonological skills, phonological awareness

Recent research in literacy and developmental disabilities has challenged the assumption that children with intellectual disabilities cannot attain functional levels of reading (Boudreau, 2002; Conners, Rosenquist, Sligh, Atwell, & Kiser, 2005; Cossu, Rossini, & Marshall, 1993; Laing, 2002; Levy, Smith, & Tager-Flusberg, 2003). However, it is clear that significant variability exists in the level of reading achievement of children with intellectual disabilities (Boudreau, 2002; Conners, 2003; Katims, 1994, 1996, 2000). Functional reading skills are critical for the success of individuals with intellectual disabilities, as reading achievement is associated with increased vocational opportunities, increased peer acceptance, and greater independence in daily living activities (Erickson, 2000; Miller, Leddy, & Leaveitt, 1999). Despite the importance of reading skills for supporting autonomy in individuals with intellectual disabilities, literacy has received little attention in fragile X syndrome, the most common inherited cause of intellectual impairment.

Fragile X Syndrome

FXS is a single gene, X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 4,000 males and 1 in 8,000 females (Sherman, Pletcher, & Driscoll, 2005; Turner, Webb, Wake, & Robinson, 1996). FXS is caused by an expansion of the cytosine-guanine-guanine trinucleotide repeat on the Fragile X Mental Retardation-1 (FMR1) gene located on the long arm of the X chromosome. In full mutation FXS, the FMR1 gene methylates, or “shuts down”, and impedes the normal production of FMRP, an important protein for brain development. Because the syndrome is X-linked, males are typically more impaired than females who have a second, functional X chromosome. Most males with FXS have moderate intellectual impairment, although cognitive ability is unevenly affected and some males demonstrate skills in the low-average range (Abbeduto & Hagerman, 1997; Hagerman, 2002; Hagerman et al., 1994). The cognitive domains of working memory (Baker et al., 2011; Lanfranchi, Cornoldi, Drigo, & Vianello, 2008; Ornstein et al., 2008), sequential processing (Burack et al., 1999; Dykens, Hodapp, & Leckman, 1987), and attention (Cornish, Scerif, & Karmiloff-Smith, 2007; Mazzocco, Pennington, & Hagerman, 1993; Ornstein et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2006) are particularly affected, with deficits in these areas greater than mental age-based expectations.

Almost all individuals with FXS exhibit some characteristic features of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), such as poor eye contact, hand flapping, hand biting, perseveration, and social and communication deficits (Hagerman et al., 1986; Merenstein et al., 1996; Reiss & Freund, 1992). Sixty to seventy-four percent of boys with FXS exhibit sufficient behaviors to meet diagnostic criteria for ASD (Klusek et al., 2014; Garcia-Nonell, 2008). ASD comorbidity in FXS has a detrimental impact on developmental outcomes, including language outcomes such as receptive (Lewis et al., 2006; Rogers, Wehner, & Hagerman, 2001), expressive (Philofsky, Hepburn, Hayes, Hagerman, & Rogers, 2004), and pragmatic language abilities (Klusek, Martin, & Losh, 2014; Losh, Martin, Klusek, Hogan-Brown, & Sideris, 2012; Roberts, Martin, et al., 2007). Although the impact of ASD on the literacy skills of individuals with FXS is unknown, poor language skills are a risk factor for reading difficulties (Bishop & Snowling, 2004; Catts & Kamhi, 2005; Nation, Clarke, Marshall, & Durand, 2004), and thus it would be expected that ASD increases the risk for literacy failure in children with FXS.

Literacy Skills of Individuals with Fragile X Syndrome

Few studies have investigated reading abilities of individuals with FXS, and little is known about processes that may support literacy in this population, such as phonological skills. However, it is clear that literacy skills are significantly impaired in FXS. In a national survey of 1,105 families of children with FXS, Bailey et al. (2009) found that only 19% of adult males with FXS were reported to read books containing new words or concepts. Significant impairments were also detected in basic literacy skills, as only 44% of adult males with FXS were reported to read basic picture books and 59% were reported to know letter sounds. Furthermore, although boys with FXS gained literacy skills from birth through age five, Bailey et al. (2009) detected a developmental plateau in the acquisition of literacy skills at around six to ten years. Similar developmental plateaus, occurring at approximately ten years of age, have been reported for the acquisition of letter/word recognition skills (Roberts et al., 2005) and phonological awareness skills (Adlof et al., 2014) in boys with FXS, suggesting literacy acquisition in FXS slows in late childhood. While reading in FXS may be delayed relative to age-based expectations, a preliminary study by Johnson-Glenberg (2008) found that word identification skills of males with FXS (n = 13) were better than those of younger, typically developing boys who were matched on nonverbal mental age. Thus, basic reading skills may be a strength for males with FXS relative to general cognitive ability.

In contrast, phonological skills (i.e., skills in “the domain of language that pertains to the elements of speech and the systems that govern structural relationship among these elements within and across words;” Scarborough & Brady, 2002, p. 303) appear to lag behind cognitive expectations. Phonological ability encompasses a broad range of skills such as the encoding of phonological information in short-term memory, the use of phonological codes in working memory, the retrieval of phonological labels from long-term memory, and the manipulation of the phonological structure of words (Adams, 1990; Catts & Kamhi, 1999; Wagner & Torgesen, 1987; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 2002). In particular, phonological awareness, or “attending to, thinking about, and intentionally manipulating the phonological aspects of spoken language” (Scarborough & Brady, 2002, p. 312), is a skill set highly predictive of reading ability in typical development (Bird, Bishop, & Freeman, 1995; Ehri & Wilce, 1985; Liberman, Shankweiler, Fischer, & Carter, 1974; Perfetti, Beck, Bell, & Hughes, 1987; Share & Stanovich, 1995). In a longitudinal investigation of phonological awareness in 54 school-aged boys with FXS, Adlof and colleagues (2014) found that boys with FXS exhibit lower level phonological awareness skills than younger, mental-age matched typically developing boys. However, no group differences were detected in the rate of change over time, indicating that phonological awareness growth in FXS is commensurate with cognitive development.

Phonological skills in FXS may also be weaker than would be expected based on basic reading abilities. Johnson-Glenberg (2008) found that boys with FXS (n = 13) who were matched with typically developing children on word identification skills showed phonological decoding skills (measured by performance on a word attack task) that lagged behind those of the controls by about two years. Clinical reports by Braden (2002) and Spiridigliozzi, et al. (1994) have also supported weaknesses in word decoding skills and relative strengths in familiar word decoding in FXS. Given these reports, it has been suggested that children with FXS rely on different sub-processes to identify words than do typically developing children, with greater dependence on a gestalt or “whole-word” approach to word decoding. Yet, emerging evidence suggests that, despite relative weaknesses in this domain, phonological ability may be an important predictor of reading achievement in FXS. In one study of 54 boys with FXS, phonological awareness accounted for significant variability in both concurrent and later letter/word identification skills (Adlof et al., 2014).

Potential impact of ASD on literacy in FXS

As previously discussed, individuals with FXS are at elevated risk for ASD and relatively little is known about the impact of ASD symptoms on literacy skills in FXS, despite a documented impact of ASD symptoms on language outcomes in this population. Research in this area is limited to a single report by Adlof and colleagues (2014), which did not find evidence that ASD symptoms influenced the level or rate of phonological awareness growth in a sample of 54 school-aged boys with FXS. ASD symptoms have not yet been examined as potential contributors to reading or other phonological deficits in FXS. In idiopathic ASD, there is a significant variability in literacy level that is consistent with the substantial clinical heterogeneity seen in the disorder (Nation et. al., 2006). Among high-functioning individuals, basic reading skills generally fall within the average range, whereas reading comprehension is often impaired (Huerner & Mann, 2010; Nation et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2009). However, not all individuals have basic reading skills that are within normal limits; Nation et al. (2006) examined children with ASD of all functioning levels and found that about 20% were completely unable to read. Thus, literacy is impaired in idiopathic ASD and it is possible that ASD symptoms may negatively impact literacy achievement in FXS.

The Present Study

While existing publications shed some light on the literacy profile of individuals with FXS, research is needed to more fully investigate patterns of strengths and weaknesses, areas of atypical development, and predictors of literacy achievement in this population. This study addressed the following questions:

What is the level of reading and phonological ability in school-aged boys with FXS?

Do reading and phonological skills of boys with FXS differ from those of typically developing boys matched on nonverbal cognitive ability?

What are strengths and weaknesses of the reading and phonological profiles among boys with FXS?

Do phonological awareness skills (i.e., explicit knowledge of individual phonemes within words) predict reading ability in boys with FXS?

What is the impact of ASD symptoms on the reading and phonological skills of boys with FXS?

Methods

Participants

Fifty-one boys with full mutation fragile X syndrome (FXS) and a control group of 35 mental age-matched boys with typical development (TD) were drawn from a larger longitudinal study of development and achievement in children with FXS. Participants with FXS were recruited through genetics clinics, developmental evaluation centers, and early intervention programs in the Southeastern United States. The diagnosis of full mutation FXS was confirmed by DNA report. Participants with TD were recruited from childcare centers, preschools, and local elementary schools.

The larger study employed a group matching procedure, where participants meeting study criteria were enrolled until pre-determined recruitment goals were achieved. The mean nonverbal mental ages of the groups were examined periodically during ongoing recruitment and targets were honed as necessary to prioritize enrollment of participants who best facilitated group-level matching, based on caregiver report during initial phone screening. This strategy was successful and resulted in groups well matched on nonverbal mental age, according to the criteria outlined by Mervis & Robinson (2003) with a p-value >.50. All FXS and TD participants with available literacy data were included in the present study and these groups did not differ on nonverbal mental age (p = .628) as measured with the Brief IQ Scale of the Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (Leiter-R; Roid & Miller, 1997). The mean age of the boys with FXS was 10.2 years (range 7.9-13.2) and 5.1 years (range 3.3-7.4) for the boys with TD; the groups differed significantly in chronological age (p = .001). The maternal education level of the groups also differed; this variable was controlled for in analyses. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Phonological awareness data from a subset of the participants in this study have been previously reported in a longitudinal study of phonological awareness in Adlof et al. (2014).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Group | Test of Group Differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FXS n = 51 | TD n = 35 | p-value | |

| Chronological Age (years) | .001 | ||

| M (SD) | 10.2 (1.7) | 5.1 (0.8) | |

| Range | 7.9–13.2 | 3.3–7.4 | |

| Nonverbal Mental Age1 (years) | .628 | ||

| M (SD) | 5.4 (0.6) | 5.2 (0.8) | |

| Range | 4.1–6.7 | 3.7–7.5 | |

| IQ2 | .001 | ||

| M (SD) | 56.0 (10.47) | 107.7 (8.77) | |

| Range | 36.0-74.0 | 85.0-123.0 | |

| CARS | n/a | ||

| M (SD) | 27.5 (4.5) | -- | |

| Range | 17.5–37.5 | ||

| Ethnicity [% (n)] | .723 | ||

| European American | 82.3 (42) | 88.5 (31) | |

| African American | 13.7 (7) | 8.6 (3) | |

| Hispanic | 2.0 (1) | 2.9 (1) | |

| Asian American | 2.0 (1) | -- | |

| Maternal Education [% (n)] | .003 | ||

| High school or less | 20.0 (39.2) | 4.0 (11.4) | |

| Some college | 18.0 (35.3) | 11.0 (31.4) | |

| College degree or higher | 11.0 (21.6) | 20.0 (57.2) | |

| Not reported | 2.0 (3.9) | -- | |

Note.

Brief IQ Age equivalent on the Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised

Brief IQ Standard Score on the Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised

CARS = Childhood Autism Rating Scale

Procedures

Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Assessments were administered as part of a broader protocol by trained research associates (most of whom were either doctoral or master's level clinicians). To increase compliance, assessments took place at the child's school during regular school hours.

Measures

Nonverbal cognition

The Brief IQ composite of the Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (Leiter-R; Roid & Miller, 1997) was used to measure nonverbal cognitive ability. The present study sought to elucidate how children with FXS differed from children of a similar developmental level on measures of reading and phonology. The Leiter-R, a nonverbal cognitive measure, was chosen as the most optimal index of intellectual functioning for the present analyses, given the potential for language-based assessment to create bias or reduce accuracy in the cognitive appraisal of populations with known language impairments, such as FXS (i.e., Hooper et al., 2000). The Leiter-R Brief IQ is comprised of four subscales: Figure Ground, Form Completion, Sequential Order, and Repeated Patterns. The psychometric properties of the Leiter-R Brief IQ are excellent, with Cronbach's alphas ranging from 0.75-0.88 across subtests and support for concurrent validity (Tsatsanis et al., 2003; Hooper & Bell, 2006). The Leiter-R has been used extensively to characterize cognitive ability in populations with intellectual disabilities, including FXS (e.g., Glenn & Cunningham, 2005; Hooper et al., 2000; Skinner et al., 2005). Age equivalent scores were used in analysis.

Reading

Three subtests of the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Academic Achievement-Revised (WJ-R; Woodcock & Johnson, 1990) were used to measure reading skills: Letter-Word Identification, Passage Comprehension, and Word Attack. Scores from Letter-Word Identification and Passage Comprehension subtests were combined to form a Broad Reading composite score, the primary dependent variable examined. The Letter-Word Identification subtest measures symbol recognition, letter naming, and word naming. The Passage Comprehension subtest measures reading comprehension and vocabulary skills. Initial items require children to point to one picture from a choice of four represented by a phrase, while more difficult items measure their ability to provide a missing word in a passage. The Word Attack subtest measures decoding skills by requiring children to use knowledge of grapheme-phoneme correspondence to correctly decode unfamiliar (nonsense) words such as “jop” or “shamble”. Although word attack tasks involve phonological decoding skills, this subtest was considered a “reading” task in this paper as it measures the ability to decode novel words (based on the assumption that decoding nonsense words requires the same cognitive processes as decoding a real novel word). Standard scores were used in analyses describing the performance of the FXS group compared to age-based expectations; W scores were used in group comparisons and predictive analyses (see Data Analysis). W scores are computed through a mathematical transformation of raw scores into Rasch-model scores, providing a mechanism to represent both the child's degree of mastery as well as item difficulty. The scores are centered at 500 for a ten year-old child. Because each possible raw score of the test is associated with a unique W score, the use of W scores may help resist floor effects by allowing for greater variability at the lower tail of performance to be captured than would standard scores. W scores also possess favorable psychometric properties in that they are norm-referenced (unlike raw scores) and on an equal-interval scale (unlike age equivalent scores); see Jaffe (2009).

Phonological skills

Four subtests from the Woodcock Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities-Third Edition (WJ-III; Woodcock et al., 2001) were used to index phonological ability: Sound Blending, Incomplete Words, Memory for Words, and Rapid Picture Naming. The combined scores from the Sound Blending and Incomplete Word subtests were used to calculate the Phonemic Awareness composite score, which was used as an index of overall phonological awareness skill. The Sound Blending subtest assesses skills in synthesizing sounds. For example, the participant is given the sounds “/k/ /a/ /t/?” and asked what word they make when put together. The Incomplete Words subtest involves naming a complete word when given the word with missing phonemes, such as “What word am I trying to say? Alli_a_or?”. The Memory for Words subtest measures short-term phonological memory by requiring the participant to repeat an increasingly longer series of syntactically and semantically unrelated words. The Rapid Picture Naming subtest assesses phonological processing skills through the naming of pictures of objects as quickly and accurately as possible. Standard scores and W scores were used in analyses (see Data Analysis).

ASD symptoms

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler et al., 1988) assessed behavioral symptoms consistent with ASD. The CARS consists of 15 items that tap specific behaviors characteristic of ASD (e.g., relating to people, adaptation to change, verbal and nonverbal communication). Each item is rated on a scale from 1-4 and total scores above 30 are consistent with a diagnosis of ASD. Ten of the 51 boys with FXS (20%) scored above the cut-off for ASD. Prior research supports the utility of the CARS for capturing a continuum of autistic behaviors within individuals with a variety of developmental disorders, including FXS (e.g., Rellini, Tortolani, Trillo, Carbone, & Montecchi, 2004; Hatton et al., 2006; Sloneem, Oliver, Udwin, & Woodcock, 2011). Consistent with this work, this study used the CARS total score as a continuous index of autism symptom severity. Ratings were completed by consensus of two examiners immediately following the assessment. CARS data were not collected for the boys with TD, owing to the expected lack of ASD symptoms.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the performance of the boys with FXS on the standardized assessments in comparison to published norms, using standardized scores. Then, Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) was used to test group differences on the mean W scores for the reading and phonological subtests, controlling for mental age and maternal education level (indexed as a continuous variable representing the number of years of formal education). Potential false discovery rate was controlled for at the model level with the Benjamini-Hochberg method (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Effect sizes (Cohen's d) were computed; generally, an effect size of “0.2” is considered small, “0.5” medium, and effects of “0.8” or greater are considered to be large (Cohen, 1988). Next, patterns of strengths and weaknesses in reading and phonological skills in the FXS group were tested with a series of dependent-samples t-tests, using W scores. Multiple comparisons were controlled using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Then, a series of multiple regression models were used to examine phonological awareness (indexed by the Phonemic Awareness composite of the WJ-III) as a predictor of readings skills (i.e., Letter-Word Identification, Passage Comprehension, Word Attack, and the Broad Reading composite of the WJ-R) in FXS, after controlling for mental age and maternal education level. Finally, ASD symptoms were examined as a predictor of literacy skills in the group with FXS, controlling for mental age and maternal education level. For each regression model, multicollinearity among predictors was evaluated via tolerance statistics, with no indication of problems related to multicollinearity.

Results

Literacy Skills in FXS Relative to Chronological Age-Based Norms

Reading skills

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for the reading measures are presented in Table 2. Reading skills were substantially delayed for the majority of the boys with FXS; 92% of the boys obtained a Broad Reading standard score that was two standard deviations or more below the mean, with an average Broad Reading score of 41.1 (SD = 19.0). On the Letter-Word Identification subtest, the average standard score was 45.9 (SD = 18.6). Letter-Word Identification scores ranged from 3-84, with 94% scoring two standard deviations or more below the mean. On the Passage Comprehension subtest, the average standard score was 44.0 (SD = 19.1). Ninety-two percent of the boys scored two or more standard deviations below the mean on this subtest. Finally, 98% (49 of 51) of the boys had Word Attack scores that were two or more standard deviations below the mean, with the group average at 57.6 (SD = 13.0). The percentage of boys with FXS scoring within normal limits (i.e., greater than or equal to 85, within one standard deviation of the mean) on the reading subtests were as follows: 2% for Broad Reading, 0% for Letter-Word Identification, 2% for Passage Comprehension, and 2% for Word Attack.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of group performance on the reading measures

| WJ-R Subtest |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Letter-Word Identification |

Passage Comprehension |

Word Attack |

Broad Reading Composite |

||||

| W scores | Standard scores | W scores | Standard scores | W scores | Standard scores | W scores | Standard scores | |

| FXS | n = 51 | n = 51 | n = 49 | n = 51 | ||||

| M (SD) | 398.8 (31.2) | 45.9 (18.6) | 409.5 (39.2) | 44.0 (19.1) | 440.8 (11.0) | 57.6 (13.0) | 404.1 (27.8) | 41.1 (19.0) |

| Range | 335-450 | 3-84 | 380-477 | 9-95 | 436-479 | 40-91 | 362-464 | 2-86 |

| TD | n = 35 | n = 32 | n = 32 | n = 35 | ||||

| M (SD) | 391.0 (20.6) | 104.9 (12.4) | 394.7 (21.2) | 113.7 (25.9) | 440.4 (10.5) | 104.2 (30.3) | 392.9 (17.9) | 113.2 (22.0) |

| Range | 356-450 | 82-133 | 350-470 | 88-200 | 436-477 | 81-200 | 368-460 | 89-183 |

Phonological skills

A wide range of phonological skills (see Table 3) was evident, with standard scores on the Phonemic Awareness composite ranging from 5-117. Forty-four percent of the boys exhibited significant delays in phonological awareness as evidenced by a standard score greater than or equal to two standard deviations below the mean on this composite. Forty-seven percent scored two standard deviations below the mean on the Sound Blending subtest, 30% for Incomplete Words, 98% for Memory for Words, and 55% for Rapid Picture Naming. The percentage of boys with FXS scoring within normal limits on the phonological subtests of the WJ-III are as follows: 22% for Sound Blending, 49% for Incomplete Words, 0% for Memory for Words, 20% for Rapid Picture Naming, and 27% for the Phonemic Awareness composite.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of group performance on the phonological measures

| WJ-III Subtest |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Sound Blending |

Incomplete words |

Memory for Words |

Rapid Picture Naming |

Phonemic Awareness Composite |

|||||

| W scores | Standard scores | W scores | Standard scores | W scores | Standard scores | W scores | Standard scores | W scores | Standard scores | |

| FXS | n = 51 | n = 50 | n = 51 | n = 49 | n = 48 | |||||

| M (SD) | 473.6 (21.2) | 65.2 (25.2) | 486.8 (17.5) | 78.1 (25.7) | 421.7 (20.0) | 43.2 (14.4) | 468.9 (18.4) | 67.0 (20.2) | 482.1 (16.1) | 69.0 (24.4) |

| Range | 430-512 | 11-116 | 438-515 | 1-119 | 378-470 | 12-80 | 431-507 | 30-107 | 448-507 | 5-117 |

| TD | n = 35 | n = 35 | n = 34 | n = 35 | n = 35 | |||||

| M (SD) | 488.7 (10.7) | 115.6 (16.8) | 493.0 (9.3) | 115.5 (13.5) | 467.6 (20.7) | 104.8 (11.5) | 471.9 (12.9) | 102.2 (11.9) | 490.7 (8.1) | 119.7 (12.1) |

| Range | 472-528 | 97-186 | 478-515 | 87-150 | 426-507 | 82-134 | 442-498 | 81-127 | 476-511 | 95-154 |

Literacy Skills in FXS Relative to Mental Age-Matched Typically Developing Children

Reading skills

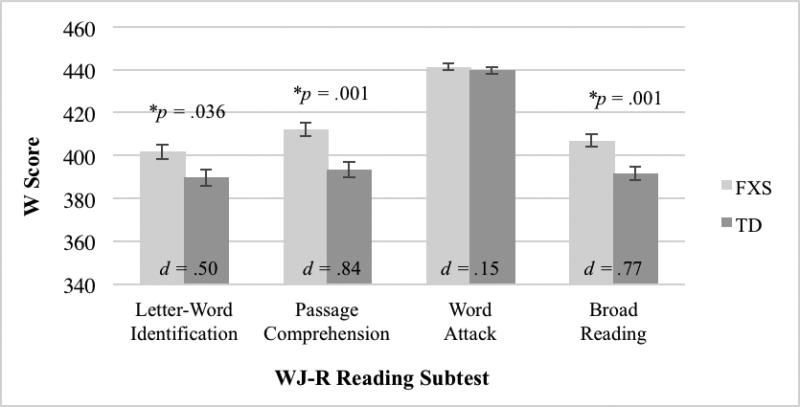

MANCOVA indicated a significant group effect on the WJ-R reading scores after covarying for mental age and maternal education (Pillai's Trace = 0.90, F [3, 76] = 215.05, p < .001). Univariate analysis on individual subtests showed a significant group effect for the Broad Reading composite (F [1, 82] = 10.95, p < .001), with the boys with FXS exhibiting more advanced reading skills than the boys with TD (d = .77). The boys with FXS also showed stronger performance on the Passage Comprehension subtest (F [1, 82] = 12.98, p = .001; d = .84) and the Letter-Word Identification subtest (F [1, 82] = 4.55, p = .036; d = .50). Word Attack performance did not differ across the groups (p = .515, d =.25). Group comparisons and effect sizes are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Group comparisons on readings subtests of the WJ-R. Covariate-adjusted means, controlling for nonverbal mental age and maternal education level, are presented.

Phonological skills

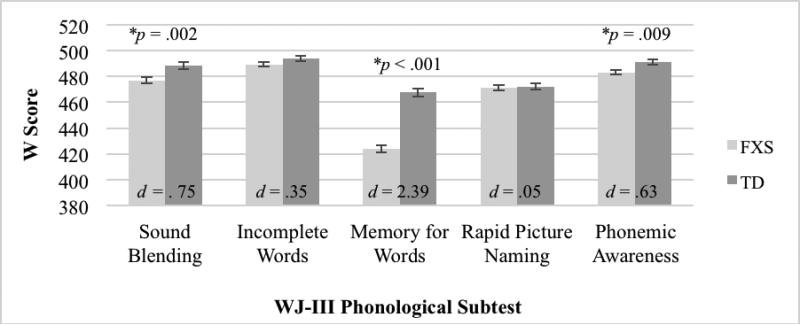

MANCOVA indicated a significant group effect on the WJ-III phonological subtests (Pillai's Trace = 0.63, F [7, 71] = 24.48, p < .001). Univariate analysis of individual subtests showed significant group effects for the Phonemic Awareness composite (F [1, 75] = 7.13, p = .009, d = .63) as well as for Sound Blending (F [1, 75] = 9.98, p = .002, d = .75) and Memory for Words (F [1, 75] = 101.24, p < .001, d =2.39), with lower skills in the group with FXS relative to TD. The groups did not differ on Incomplete Words (p = .140, d =.35) or Rapid Picture Naming (p=.836, d =.05) performance. Figure 2 presents groups comparisons and effect sizes.

Figure 2.

Group comparisons on phonological subtests of the WJ-III. Covariate-adjusted means, controlling for nonverbal mental age and maternal education level, are presented.

Literacy Strengths and Weaknesses in FXS

Reading skills

Performance across the reading subtests differed significantly in the boys with FXS, with the strongest performance on Word Attack, followed by Passage Comprehension, and then Letter-Word Identification (ps < .002).

Phonological skills

Performance on the Incomplete Words subtest was a relative strength, with significantly higher performance on this subtest than each of the other phonological subtests of the WJ-III (ps < .001). In contrast, short-term phonological memory was a relative weakness, with significantly poorer performance on the Memory for Words subtest than the other subtests (ps < .001). Significant differences were detected in performance on each of the phonological subtests, with the highest performance in Incomplete Words, followed by Sound Blending, Rapid Picture Naming, and Memory for Words (ps < .032).

Phonological Awareness as a Predictor of Reading Ability in Boys with FXS

In the group with FXS, phonological awareness accounted for 14% of the variance in Broad Reading skills above and beyond the effects of mental age and maternal education (ΔF [1, 42] = 12.05, p = .001). Phonological awareness also accounted for significant variance in the component Broad Reading subtests: Letter Word Identification (ΔF [1, 2] = 9.13, p = .004; ΔR2 = .14) and Passage Comprehension (ΔF [1, 42] = 9.29, p = .004; ΔR2 = .11). Phonological awareness did not account for unique variance in Word Attack skills (ΔF [1, 40] = 0.93, p = .341).

ASD Symptoms as a Predictor of Literacy in Boys with FXS

ASD symptoms did not account for additional variance in reading skills on the Broad Reading (p = .254), Passage Comprehension (p = .761), Letter-Word Identification (p = .106), or Word Attack (p = .485) subtests of the WJ-R beyond the effects of mental age and maternal education. For the phonological subtests of the WJ-III, elevated ASD symptoms predicted poorer performance on Sound Blending (ΔF [1,44] = 4.59, p = .038; ΔR2 = .06), Incomplete Words (ΔF [1,44] = 4.469, p = .040; ΔR2 = .06), and Rapid Picture Naming (ΔF [1,43] = 7.29, p = .010; ΔR2 = .09), after controlling for mental age and maternal education level. A trend was detected for ASD symptoms as a predictor of performance on the Phonemic Awareness composite (ΔF [1,42] = 3.03, p = .089; ΔR2 = .05). ASD symptoms were not a significant predictor of performance on the Memory for Words subtest (p = .116).

Discussion

This study aimed to (a) describe the level of literacy achievement and profiles of strengths and weaknesses among school-aged boys with FXS, (b) determine whether boys with FXS exhibit impaired literacy skills relative to younger, mental-age matched boys with TD, (c) determine whether phonological awareness skills predict reading ability in FXS, and (d) determine the impact of ASD symptoms on the literacy skills of boys with FXS. Although the reading skills of the boys with FXS were substantially delayed relative to chronological-age expectations, comparison with younger, mental age-matched boys with TD suggested that reading ability in FXS is on par with cognitive expectations (and on some subdomains, such as passage comprehension and letter-word identification, performance is more advanced than would be expected). In contrast, the boys with FXS exhibited phonological skills that were weaker than would be expected given cognitive ability. Despite apparent weaknesses in phonological ability, skills within this domain emerged as an important predictor of reading success; phonological awareness accounted for ~15% of variance in reading skills, above and beyond the effects of mental age and maternal education level. Overall, ASD symptoms did not impact the reading abilities of the boys with FXS, whereas a number of phonological skills were influenced by ASD symptoms.

Literacy Level in Boys with FXS

Considerable within-syndrome variation was detected, with standard scores ranging from average to clinically impaired. While a small percentage of boys had reading skills within normal limits (~2%), the vast majority of boys with FXS (i.e., 92-98%) exhibited significant delays. The finding of impaired reading performance on standardized tests corroborates evidence from caregiver-report indicating that the majority of males with FXS could not read books containing novel words or concepts (Bailey et al., 2009). While few boys with FXS performed within normal limits on the reading subtests of the WJ-R, about a fourth of the boys scored within one standard deviation of the mean on the phonological subtests of the WJ-III, with considerable variability across individual subtests. The standard scores of the relatively large sample in this study show that boys with FXS are not only capable of acquiring phonological skills, but a minority have phonological abilities that are on par with age-based expectations (0-49% across phonological subtests).

Profile of Literacy Strengths and Weaknesses

Short-term phonological working memory (measured with the Memory for Words subtest) emerged as a weakness relative to all other phonological skills tested. Performance on this subtest was significantly impaired (i.e., two standard deviations below the mean) for nearly all of the boys with FXS, and none scored within normal limits on this measure. Working memory impairments are well documented in FXS (Baker et al., 2011; Hooper et al., 2008; Ornstein et al., 2008), with some evidence suggesting disproportionately affected phonological working memory relative to other domains, such as visuospatial working memory (Pierpont, Richmond, Abbeduto, Kover, & Brown, 2011). Auditory working memory has been found to contribute to poor language functioning in children with other neurodevelopmental disabilities (Conners, Rosenquist, & Taylor, 2001) and may play a role in literacy attainment as well. In contrast, phonetic processing on the Incomplete Words subtest was a strength relative to other phonological skills, with nearly half of the boys with FXS scoring within one standard deviation of the mean. This subtest indexes the ability to extract linguistic features such as the placement and manner of articulation of consonants. While very few prior studies have reported on the processing of phonetic information in FXS, others have found the production of phonological sounds and patterns to be on par with cognitive expectations in boys with FXS (Barnes et al., 2009; Barnes, Roberts, Mirrett, Sideris, & Misenheimer, 2006).

Given prior reports suggesting weaknesses in phonological decoding relative to whole-word decoding (e.g., Braden 2002; Johnson-Glenberg, 2008; Spiridigliozzi, et al., 1994), it is unexpected that Work Attack was a relative reading strength for the boys with FXS. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution as the Word Attack scores across both groups represented floor-level performance on that subtest. Although it is possible to compare performance across WJ-R subtests because they are centered at approximately the same time point, the range of possible scores differs across the subtests; Word Attack is a later-emerging skill and thus W scores for this subtest do not extend as low as those of the other reading subtests examined. Because the intent of this study was to characterize literacy skills in boys with FXS as a population, we felt that it was important to include all participants, even those who did not obtain a basal on some subtests.

Group Comparisons

Although significant delays were detected relative to age-based norms, comparison with a mental age-matched sample of younger children with TD indicated that the reading levels of boys with FXS were on par with or better than mental age-based expectations. The boys with FXS outperformed the boys with TD on Passage Comprehension and the Broad Reading composite, and did not differ from the boys with TD on Letter-Word Identification. Phonological word decoding (i.e., word attack performance) in FXS was commensurate with cognitive expectations, which contrasts with prior clinical and preliminary reports that have suggested phonological word decoding weaknesses in this population (e.g., Braden 2002; Johnson-Glenberg, 2008; Spiridigliozzi, et al., 1994). These findings show that individuals with FXS are capable of achieving reading skills at or beyond cognitive expectations, diminishing the importance of IQ in any consideration of their underlying phonological processes and overall reading capabilities. The higher scores obtained by the boys with FXS may be related to their older chronological ages and longer exposure to print; indeed, chronological age has been found to account for variance in reading attainment in other developmental disabilities such as Down syndrome (Boudreau, 2002). This finding is nonetheless considerable, given that deficits in related language domains, such as oral (i.e., expressive) language, persist even when older children with FXS are compared to younger mental age-matched controls (Roberts, Chapman, & Warren, 2008; Roberts, Hennon, et al., 2007).

Phonological difficulties in FXS persisted even when mental age was controlled, suggesting that cognitive factors alone cannot account for poor performance on phonological tasks in FXS. In particular, short-term phonological working memory assessed via the Memory for Words subtest was a weakness relative to other phonological skills tested, and the robust effect size (2.39) detected in group comparisons of this domain supports phonological working memory as an area of difficulty for boys with FXS. Weakness relative to the mental age-matched boys with TD was also detected in synthesizing sounds (Sound Blending subtest). Given that a whole-word over phonological-based approach to literacy instruction is often recommended in the education of individuals with FXS (e.g., Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium on Clinical Practices, 2012), it is possible that the weak phonological skills exhibited by the boys with FXS are related to a lack of formal instruction in this area.

Predictors of Literacy Skills in FXS

Phonological awareness skills predicted performance on three of the four reading tasks, accounting for 11-14% of the variance in reading skills. This is consistent with a number of studies supporting phonological awareness as a key ingredient for reading success in typical development (Ehri, Nunes, Stahl, & Willows, 2001; Ehri, Nunes, Willows, et al., 2001), as well as emerging evidence supporting the efficacy of a phonological-based approach in the literacy instruction of individuals with other intellectual disabilities such as Down syndrome (Browder, Wakeman, Spooner, Ahlgrim-Delzell, & Algozzine, 2006; Cupples & Iacono, 2002; Lemons & Fuchs, 2010). Findings suggest that phonological skills are critical to the reading success of individuals with FXS and highlight the need for intervention studies to evaluate the effectiveness of phonological-based approaches to literacy instruction for individuals with FXS. Findings also indicated that greater ASD symptom severity predicted poorer performance on several of the phonological tasks, although it was not predictive of the reading variables.

Future Directions

This study is the first to examine reading and phonological skills in a relatively large sample of boys with FXS, providing a starting point for understanding profiles and predictors of literacy ability in this population. Several methodological considerations should be taken into account when interpreting the results of the present study. First, ASD characterization in future work might be strengthened through the use of standardized autism severity metrics, such as that provided by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale (Lord, Rutter, DeLavore, & Risi, 2001). Although the CARS total score has been widely used as a continuous measure of ASD symptoms (e.g., Bailey et al. 2001, Hatton et al., 2009, Hatton et al., 2006; Sullivan et al., 2007), raw totals may be more influenced by participant demographics, such as IQ, than are calibrated severity metrics (Gotham, Pickles, & Lord, 2009). Secondly, potential floor effects may have influenced findings, particularly considering the difficulty in identifying literacy measures that are sensitive to variation among individuals with significant intellectual disabilities. However, the use of W scores strengthened our ability to detect variability, as W scores are on an equal interval scale (unlike age equivalent scores) and are norm-referenced (unlike raw scores), allowing for more robust statistical modeling.

It is also notable that participants with FXS were older than their mental age-matched peers, and therefore presumably had greater exposure to print and more years of formal literacy instruction; the observed literacy strengths in the group with FXS may be attributable, in part, to their older age. The choice of comparison group is a challenge inherent to intellectual disabilities research. The inclusion of younger, mental age-matched typically developing controls permit matching on relevant cognitive domains, although this approach inevitably leads to a mismatch in the chronological age of the groups (e.g., Hodapp & Dykens, 2001). The inclusion of comparison groups comprised of children with other developmental disabilities is a method that may be utilized in future work to circumvent potential age confounds, as this strategy allows for both mental-age and chronological-age matching within the same sample.

Important next steps of this work include investigation into the types of literacy instruction received by individuals with FXS in schools; anecdotally, our clinical experience suggests that there is great variability in the types of literacy instruction received by individuals with FXS, as well as variability in related factors such as classroom type, teacher training, and the home literacy environment. There is also a critical need for intervention research to determine the relative effectiveness of phonics versus whole-word literacy instruction for children with FXS. Phonetics-based approaches have proven successful for other developmental disability groups, including populations such as Down syndrome who have known relative weaknesses in phonological skills (e.g., Conners et al., 2005; Cupples & Iacono, 2002). For instance, in an intriguing intervention study, Cupples and Iacono (2002) found that although the reading skills of children with Down syndrome improved with both phonetics- and whole-word-based instructional approaches, only those children who were taught with the phonetics-based approach were able to generalize skills to reading novel words. Notably, the children with Down syndrome benefited from phonetics-based instruction, despite documented weaknesses in phonological skills (indexed by poor auditory working memory ability). Thus, phonological weaknesses do not necessarily preclude children from benefiting from phonetics-based instruction, and the findings of the present study suggest that a phonetics-based approach may be indicated for children with FXS as well. In summary, the present study demonstrates that individuals with FXS are capable of achieving reading and phonological skills, underscoring the importance of targeted, evidence-based literacy instruction for individuals with FXS.

Acknowledgements

This research supported by the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services of the U.S. Department of Education Grant (H324C010007), the National Institutes of Health (F32DC013934; R01MH090194; R01HD40602; R01HD024356). Components of this paper were completed as part of the dissertation of Anna L. Hunt (Williams) at the School of Education, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We would like to acknowledge John Sideris for his assistance with the statistical models for earlier drafts of this manuscript. We also thank the children and families who participated in this research.

Footnotes

Integrity of Research and Reporting

Study procedures were approved but the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Informed consent was obtained prior to inclusion of the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Jessica Klusek, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Anna W. Hunt, Clarity: The Speech, Hearing, and Learning Center, Greenville, SC, USA

Penny L. Mirrett, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Deborah D. Hatton, Kennedy Center, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

Stephen R. Hooper, Department of Psychiatry and Department of Allied Health Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Jane E. Roberts, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA

Donald B. Bailey, Jr., RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA

References

- Abbeduto L, Hagerman RJ. Language and communication in fragile X syndrome. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 1997;3(4):313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Adams MJ. Learning to read: Thinking and learning about print. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Adlof S, Klusek J, Shinkareva SV, Mounts M, Hatton D, Roberts JE. Phonological awareness and reading in boys with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12267. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Raspa M, Holiday D, Bishop E, Olmsted M. Functional skills of individuals with fragile x syndrome: a lifespan cross-sectional analysis. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;114(4):289–303. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-114.4.289-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SW, Hooper SR, Skinner ML, Hatton DD, Schaaf J, Ornstein P, Bailey D. Working memory subsystems and task complexity in young males with Fragile X Syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2011;55:19–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes E, Roberts JE, Long SH, Martin GE, Berni MC, Mandulak KC. Phonological accuracy and intelligibility in connected speech of boys with fragile X syndrome or Down syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52(4):1048–1061. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes EF, Roberts JE, Mirrett P, Sideris J, Misenheimer J. A comparison of oral structure and oral-motor function in young males with fragile X syndrome and Down syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing research. 2006;49(4):903–917. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/065). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Jr, Hatton DD, Skinner M, Mesibov G. Autistic behavior, FMR1 protein, and developmental trajectories in young males with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001;31:165–174. doi: 10.1023/a:1010747131386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bird J, Bishop DVM, Freeman NH. Phonological awareness and literacy development in children with expressive phonological impairments. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1995;38:446–462. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3802.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DV, Snowling MJ. Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: Same or different? Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(6):858. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau D. Literacy skills in children ad adolescents with Down syndrome. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2002;15:497–525. [Google Scholar]

- Braden ML. Academic interventions. Fragile X syndrome: Diagnosis, treatment, and research. 2002:428–464. [Google Scholar]

- Braden ML. Academic interventions. In: Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, editors. In Fragile X syndrome: Diagnosis, treatment, and research. JHU Press; Baltimore, MD: 2002. pp. 428–464. [Google Scholar]

- Browder DM, Wakeman SY, Spooner F, Ahlgrim-Delzell L, Algozzine B. Research on reading instruction for individuals with significant cognitive disabilities. Exceptional children. 2006;72(4):392–408. [Google Scholar]

- Burack JA, Shulman C, Katzir E, Schaap T, Iarocci G, Amiri PN. Cognitive and behavioural development of Israeli males with fragile X and Down syndrome. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1999;23:519–531. [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW, Kamhi AG. Language and reading disabilities: A developmental perspective. Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW, Kamhi AG. The connections between language and reading disabilities. Psychology Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition. Psychology Press; Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Conners FA. Reading skills and cognitive abilities of individuals with mental retardation. In: Abbeduto L, editor. International review of research in mental retardation. Vol. 27. Academic Press; San Diego: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Conners FA, Rosenquist CJ, Sligh AC, Atwell JA, Kiser T. Phonological reading skills acquisition by children with mental retardation. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;27:121–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners FA, Rosenquist CJ, Taylor Memory training for children with Down syndrome. Downs Syndrome Research and Practice. 2001;7:25–33. doi: 10.3104/reports.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish K, Scerif G, Karmiloff-Smith A. Tracing syndrome-specific trajectories of attention across the lifespan. Cortex. 2007;43(6):672–685. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossu G, Rossini F, Marshall JC. When reading is acquired but phoneme awareness is not: A study of literacy on Down's syndrome. Cognition. 1993;46:129–138. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(93)90016-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupples L, Iacono TA. The efficacy of “whole word” versus “analytic” reading instruction for children with Down syndrome. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2002;15:549–574. [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Hodapp RM, Leckman JF. Strengths and weaknesses in the intellectual functioning of males with fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1987;92(2):234–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehri LC, Nunes SR, Stahl SA, Willows DM. Systematic phonics instruction helps students learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel's meta-analysis. Review of educational research. 2001;71(3):393–447. [Google Scholar]

- Ehri LC, Nunes SR, Willows DM, Schuster BV, Yaghoub-Zadeh Z, Shanahan T. Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel's meta- analysis. Reading research quarterly. 2001;36(3):250–287. [Google Scholar]

- Ehri LC, Wilce LS. Movement into reading: Is the first stage of printed word learning visual or phonetic. Reading Research Quarterly. 1985;20:163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KA. All children are ready to learn: An emergent versus readiness perspective in early literacy assessment. Seminars in Speech and Language. 2000;21:193–202. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-13193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium on Clinical Practices [April 2, 2014];Educational guidelines for fragile X syndrome: Preschool through elementary students. 2012 2012, from http://www.fragilex.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Educational-Guidelines-for-Fragile-X-Syndrome-Preschool-Elem2012-Oct.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- García-Nonell C, Ratera ER, Harris S, Hessl D, Ono MY, et al. Secondary medical diagnosis in fragile X syndrome with and without autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2008;146(15):1911–1916. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn S, Cunningham C. Performance of young people with Down syndrome on the Leiter- R and British picture vocabulary scales. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49(4):239–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Pickles A, Lord C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a meaure of severity in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:693–705. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman R. The physical and behavioral phenotype. In: Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, editors. Fragile X Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research Third Edition. Third ed. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2002. pp. 3–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman R, Hull CE, Safanda JF, arpenter I, Staley LW, O'Connor RA, Thibodeau SN. High functioning fragile X males: demonstration of an unmethylated fully expanded FMR-1 mutation associated with protein expression. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1994;51(4):298–308. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320510404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Jackson AW, Levitas A, Rimland B, Braden M, Opitz JM, Reynolds JF. An analysis of autism in fifty males with the fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1986;23(1-2):359–374. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320230128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton DD, Sideris J, Skinner M, Mankowski J, Bailey DB, Roberts J, Mirrett P. Autistic behavior in children with fragile X syndorme: Prevelence, stability, and impact of FMRP. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2006;140:1804–1813. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton DD, Wheeler A, Sideris J, Sullivan K, Reichardt A, Roberts J, Bailey DB., Jr Developmental trajectories of young girls with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;114:161–171. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-114.3.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodapp RM, Dykens EM. Strengthening behavioral research on genetic mental retardation syndomes. Journal of Mental Retardation. 2001;106:4–15. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2001)106<0004:SBROGM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SR, Hatton DD, Baranek GT, Roberts JP, Bailey DB. Nonverbal assessment of IQ, attention, and memory abilities in children with fragile-X syndrome using the Leiter-R. Psychoeducational Assessment. 2000;18:255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SR, Hatton D, Sideris J, Sullivan K, Hammer J, Shaaf J. Executive functions in young males with fragile X syndrome in comparison to mental age-matched controls: Baseline findings from a longitudinal study. Neuropsychology. 2008;22(36-47) doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper VS, Bell SM. Concurrent validity of the Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test and the Leiter International Performance Scale–Revised. Psychology in the Schools. 2006;43(2):143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Huerner SV, Mann V. A comprehensive profile of decoding and comprehension in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:485–493. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0892-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe LE. Development, interpretation, and application of the W score and the relative proficiency index (Woodcock-Johnson III Assessment Service Bulletin No. 11) Riverside Publishing; Rolling Meadows, IL: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Glenberg MC. Fragile X syndrome: Neural network models of sequencing and memory. Cognitive Systems Research. 2008;9(4):274–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cogsys.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CR, Happe F, Golden H, Marsden AJ, Tregay J, Simonoff E, et al. Reading and arithmetic in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Peaks and dips in attainment. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:718–728. doi: 10.1037/a0016360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katims D. Emergance of literacy in preschool children with disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly. 1994;17:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Katims D. The emergance of literacy in elementary students with mild ID. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 1996;96:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Katims D. Literacy instructions for people with ID: Historical highlights and contemporary analysis. Education and Training in Intellectual Disabilities and Developmental Disabilities. 2000;35:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Klusek J, Martin GE, Losh M. Consistency between research and clinical diagnoses of autism among boys and girls with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Reasearch. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jir.12121. doi: 10.1111/jir.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klusek J, Martin GE, Losh M. A comparison of pragmatic language in boys with autism and fragile X syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2014 doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-13-0064. doi:10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-13-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing E. Investigation reading development in atypical populations: The case of Williams syndrome. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2002;15:575–587. [Google Scholar]

- Lanfranchi S, Cornoldi C, Drigo S, Vianello R. Working memory in individuals with fragile X syndrome. Child Neuropsychology. 2008;15(2):105–119. doi: 10.1080/09297040802112564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemons CJ, Fuchs D. Phonological awareness of children with Down syndrome: its role in learning to read and the effectiveness of related interventions. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2010;31(2):316–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy Y, Smith J, Tager-Flusberg H. Word reading and reading related skills in adolescents with Williams syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:576–587. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P, Abbeduto L, Murphy M, Richmond E, Giles N, Bruno L, Schroeder S. Cognitive, language and social-cognitive skills of individuals with fragile X syndrome with and without autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:532–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman IY, Shankweiler D, Fischer FW, Carter B. Explicit syllable and phoneme segmentation in the young child. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1974;18:201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DeLavore PC, Risi S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Losh M, Martin GE, Klusek J, Hogan-Brown AL, Sideris J. Social communication and theory of mind in boys with autism and fragile X syndrome. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco MM, Pennington BF, Hagerman RJ. The neurocognitive phenotype of female carriers of fragile X: Additional evidence for specificity. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 1993;14(5):328–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merenstein SA, Sobesky WE, Taylor AK, Riddle JE, Tran HX, Hagerman RJ. Molecular-clinical correlations in males with an expanded FMR1 mutation. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1996;64(2):388–394. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960809)64:2<388::AID-AJMG31>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB, Robinson BF. Methodological issues in cross-group comparisons of language and/or cognitive development. In: Levy Y, Schaeffer J, editors. Language Competence across Populations: Toward a Definition of Specific Language Impairment. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JF, Leddy M, Leaveitt L, editors. Improving the communication of people with Down syndrome. Paul H. Brookes; Baltimore: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nation K, Clarke P, Marshall CM, Durand M. Hidden language impairments in children: Parallels between poor reading comprehension and specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Hearing and Language Research. 2004;47:199–211. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation K, Clarke P, Wright B, Williams C. Patterns of reading ability in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36(7):911–919. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein PA, Schaaf JM, Hooper SR, Hatton DD, Mirrett P, Bailey DB. Memory skills of boys with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113(6):439–452. doi: 10.1352/2008.113:453-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA, Beck L, Bell L, Hughes C. Phonemic knowledge and learning to read are reciprocal: A longitudinal study of first grade children. Merill-Palmer Quarterly. 1987;33:283–319. [Google Scholar]

- Philofsky A, Hepburn SL, Hayes A, Hagerman R, Rogers SJ. Linguistic and cognitive functioning and autism symptoms in young children with fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2004;109(3):208–218. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<208:LACFAA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpont EI, Richmond EK, Abbeduto L, Kover ST, Brown WT. Contributions of phonological and verbal working memory to language development in adolescents with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2011;3(4):335–347. doi: 10.1007/s11689-011-9095-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss AL, Freund L. Behavioral phenotype of fragile X syndrome: DSM-III-R autistic behavior in male children. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1992;43:35–46. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320430106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellini E, Tortolani D, Trillo S, Carbone S, Montecchi F. Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) and Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC) correspondence and conflicts with DSM-IV criteria in diagnosis of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34:703–708. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-5290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Schaaf JM, Skinner M, Wheeler A, Hooper S, Hatton DD, Bailey Jr DB. Academic skills of boys with fragile X syndrome: profiles and predictors. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2005;110:107–120. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110<107:ASOBWF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Chapman R, Warren S, editors. Speech and language development and intervention in Down syndrome and fragile X syndrome. Paul H. Brookes Publishing; Baltimore: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Hennon EA, Price J, Dear E, Anderson K, Vandergrift NA. Expressive language during conversational speech in boys with fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2007;112(1):1–17. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[1:ELDCSI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Martin GE, Moskowitz L, Harris AA, Foreman J, Nelson L. Discourse skills of boys with fragile X syndrome in comparison to boys with Down syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:475–492. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/033). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Wehner DE, Hagerman R. The behavioral phenotype in fragile X: Symptoms of autism in very young children with fragile X syndrome, idiopathic autism, and other developmental disorders. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22(6):409–417. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH, Miller LJ. Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised. Stoelting; Wood Dale, IL: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough HS, Brady SA. Toward a common terminology for talking about speech and reading: A glossary of the “phon” words and some related terms. Journal of Literacy Research. 2002;34:299–336. [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E, Reichler J, Renner B. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Share D, Stanovich K. Cognitive processes in early reading development: Accomodating individual differences into a model of acquisition. Issues in Education. 1995;1:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S, Pletcher BA, Driscoll DA. Fragile x syndrome: Diagnostic and carrier testing. Genetics in Medicine. 2005;7:584–587. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000182468.22666.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner M, Hooper S, Hatton DD, Roberts J, Mirrett P, Schaaf J, et al. Mapping nonverbal IQ in young boys with fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2005;132(1):25–32. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloneem J, Oliver C, Udwin O, Woodcock KA. Prevalence, phenomenology, aetiology, and predictors of challenging behaviour in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2011;55:138–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiridigliozzi G, Lachiewicz A, MacMordo C, Vizoso A, O'Donnell C, McConkie-Rosell A, Burgess D. Educating boys with fragile x syndrome: A guide for parents and professionals. Duke University Medical Center; Durham, NC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K, Hatton D, Hammer J, Sideris J, Hooper S, Ornstein P, Bailey D., Jr. ADHD symptoms in children with FXS. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2006;140A:2275–2288. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K, Hatton DD, Hammer J, Sideris J, Hooper S, Ornstein PA, Bailey DB. Sustained attention and response inhibition in boys with fragile X syndrome: measures of continuous performance. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2007;144:517–532. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsatsanis KD, Dartnall N, Cicchetti D, Sparrow SS, Klin A, Volkmar FR. Concurrent validity and classification accuracy of the Leiter and Leiter-R in low-functioning children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33(1):23–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022274219808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner G, Webb T, Wake S, Robinson H. Prevalence of fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1996;64(1):196–197. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960712)64:1<196::AID-AJMG35>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner RK, Torgesen JK. The nature of phonological processing and its causal role in the acquistion of reading skills. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:192–212. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, Lonigan CJ. Emergent literacy: Development from pre-readers to readers. In: Neuman SB, Dickinson DK, editors. Handbook of early literacy research. The Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock R, Johnson M. Woodcock-Johnson Psychoeducational Battery-Revised. DLM Teaching Resources; Allen, TX: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities. Riverside Publishing; Itasca, IL: 2001. [Google Scholar]