Abstract

Little research has examined the support needs of mothers versus fathers of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We identified and compared the important and unmet support needs of mothers and fathers, and evaluated their association with family and child factors, within 73 married couples who had a child or adolescent with ASD. Mothers had a higher number of important support needs and higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than fathers. Multilevel modeling indicated that child age, co-occurring behavior problems, presence of intellectual disability, parent education, and household income were related to support needs. Findings offer insight into the overlapping and unique support needs of mothers and fathers of children and adolescents with ASD.

Keywords: Autism, support, services, parent, father

Parents of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are faced with unique parenting challenges. Now the fastest growing developmental disability (Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network [ADDMN], 2014), ASD involves lifelong impairments in social communication and restricted interests or repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In addition to these core ASD symptoms, approximately one-half of children and adolescents with ASD have intellectual disability (ID) with accompanying deficits in everyday living skills (ADDMN, 2014). More than one-third of children and adolescents with ASD also exhibit clinically significant co-occurring behavior problems such as inattention, hyperactivity, and anxiety (Hartley, Sikora, & McCoy, 2008; Simonoff et al., 2008). In order to manage these symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems, assist their son or daughter with everyday living skills, and cope with family-wide effects (e.g., impacts on parents and siblings), parents often rely on formal and informal supports.

Informal supports include the wide array of advice, assistance with everyday tasks, and emotional support that parents of children and adolescents with ASD receive from family, friends, and one's spouse. In terms of formal supports, parents of children and adolescents with ASD interact with a bevy of professionals including pediatricians, speech-language pathologists, physical and occupational therapists, behavioral therapists, and special education teachers. There is broad consensus within the field of developmental disabilities that these supports should be provided in the context of family-centered care (Dunst, Trivette, & Hamby, 2007). Family-centered care emphasizes the importance of establishing relationships with parents based on mutual respect and open communication, matching the changing needs and priorities of the family, and providing parents with choices and control over treatment decisions (Arrango, 1999; Woodside, Rosenbaum, King & King, 2001). Unfortunately, the actualities of everyday practice often do not align with the tenets of family-centered care and important parent support needs go unmet (Freedman & Boyer, 2000).

Understanding the important and unmet support needs of parents of children and adolescents with ASD has implications for decreasing parenting stress and improving the psychological well-being of parents. Parent satisfaction with support services has been shown to be strongly associated with parental psychological well-being (Bromley, Hare, Davison, & Emerson, 2004). Indeed, parent ratings of satisfaction with support are more strongly related to measures of parental psychological well-being than is the actual number of support services the family receives (White & Hastings, 2004), as parent ratings may better capture the degree to which support services are family-centered. It is now well-documented that parents of children and adolescents with ASD are at risk for poor psychological well-being as compared to parents of children and adolescents without disabilities (Ekas & Whitman, 2010), and parents of children and adolescents with other types of disabilities (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Hartley, Seltzer, Head, & Abbeduto, 2012). Understanding parents’ perspectives on important and unmet support needs is a critical first step in modifying the service system to improve family outcomes.

Moreover, understanding discrepancies in the support needs of mothers and fathers within married couples has relevance for strengthening the marital relationship. Couples of children and adolescents with ASD are at an increased risk of divorce (Hartley et al., 2010). In previous studies, parents of children and adolescents indicated that their spouse was often their most important source of informal support (Brobst, Clopton, & Hendrick, 2008; Gray, 2003). Insight into the differing perspectives of mothers versus fathers in support needs can help guide interventions aimed at teaching couples how to better support one another.

To date, only a handful of studies have examined the support needs of parents of children and adolescents with ASD or other types of developmental disabilities. These studies have either exclusively examined the perspectives of mothers, or included only a small number of fathers. The support needs most commonly reported be both important and unmet across these studies include financial support, for the child/adolescent with ASD to have friends, help dealing with fears about the child/adolescent with ASD's future, access to therapies, continuous services, case management, for siblings’ friends to feel comfortable, and clearer communication by professionals (Liptak et al., 2006; Konstantareas & Homatidis, 1989; Schieve et al., 2007; Schieve et al., 2011; Sikolas & Kern, 2006).

The present study seeks to expand on previous studies by examining the support needs of fathers in addition to mothers of children and adolescents with ASD. Virtually nothing is known about the extent to which the support needs of fathers of children and adolescents with ASD are similar to those of mothers. Yet, research suggests that fathers often have different parenting experiences than mothers. Although findings are mixed, as compared to mothers, fathers of children and adolescents with ASD report lower levels of parenting stress (Dabrowska & Pisula, 2010; Woodman, 2014), more internal and stable child-related cognitive attributions about their son or daughter's behavior problems (Hartley, Schaidle, & Burnson, 2013), and spend less time providing childcare (Dyer et al., 2009; Hartley, Mihaila, Bussanich, & Otalora-Fadner, in press). Research on adults in the general population also suggests that there are gender differences in preferences for support services; for instance, as compared to men, women are more open to mental health counseling (e.g., Piko, 1998). These gender differences may also contribute to mother-father differences in support needs in families of children and adolescents with ASD.

To our knowledge, no published studies have compared the support needs of mothers and fathers of children and adolescents with ASD. However, a handful of studies using small sample sizes have examined differences in the support needs of mothers versus fathers of children and adolescents with chronic health conditions or other types of disabilities (Bailey, Blasco, & Simeronsson, 1992; Perrin, Lewkowicz, & Young, 2000). In these studies, mothers reported a higher number of support needs than fathers, and were more likely to place importance on family-wide supports (counseling for parents or siblings) than fathers.

Although mothers of children and adolescents with ASD may have a higher number of important support needs, fathers may be at risk for having their support needs go unmet. Previous studies of parent support needs in families of children and adolescents with ASD are almost exclusively focused on mothers (e.g., Liptak et al., 2006; Schieve et al., 2011; Siklos & Kern, 2006). As a result, support services are not designed to address the needs of fathers.

In addition to understanding mother-father differences in support needs, it is important to identify child and family factors related to support needs. Previous research on parents (almost exclusively mothers) of children and adolescents with a variety of types of developmental disabilities found that severity of impairments was positively related to number of important support needs (Bromley et al., 2004; Perrin et al, 2000). Among children and adolescents with ASD, a higher severity of ASD symptoms and the presence of ID may therefore be related to having a higher number of support needs. Moreover, previous studies suggest that co-occurring behavior problems are particularly stressful for parents of children and adolescents with ASD (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Lecavalier, Leone, & Wiltz, 2006); thus, a higher level of co-occurring behavior problems may also be related to a higher number of important support needs. Child age may be negatively related to number of important support needs, as younger children often require more direct supports than older children with ASD. However, child age may be positively related to the proportion of important support needs that are unmet, given the limited availability of services for older children or adolescents with ASD (Cheak-Zamora, Yang, Farmer, & Clark, 2013; Howlin, Goode, Hutton, & Rutter, 2005).

In terms of family factors, parent education and household income may influence support needs. In a recent study, the number of services that families of children and adolescents with ASD received was positively associated with parent education (Siller, Ryes, Hotez, Hutman, & Sigman, 2013). In terms of household income, the cost of interventions and treatments for children and adolescents with ASD and their family members are often not covered by insurance, and thus parents often pay out of pocket (Liptak, Stuart, & Auinger, 2006). Parents with a lower household income can afford fewer support services, and subsequently, may have a higher level of unmet important support needs than parents with a higher household income.

The aims of the present study were to: 1) identify and compare the number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet of mothers versus fathers of children and adolescents with ASD, and 2) determine the family and child factors associated with number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet. Mothers and fathers from 73 married couples who had a child or adolescent with ASD independently reported on their support needs. Parent report along with medical and educational records were used to collect information on child and family characteristics. We hypothesized that within-couples, mothers would report a higher number of important support needs than fathers, as this was found in studies on parents of children and adolescents with chronic health conditions and other types of developmental disabilities (Bailey et al., 1992; Perrin et al., 2000). In contrast, fathers were predicted to report a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than mothers, given that the design of support services is based on research on mothers. Number of ASD symptoms, presence of ID, and level of co-occurring behavior problems were predicted to be positively related to number of important support needs. Child age was predicted to be negatively related to number of important support needs but positively related to proportion of important support needs that are unmet, as support services are more limited for older children or adolescents with ASD (Cheak-Zamora et al., 2013; Howlin et al., 2005). Finally, parent education and household income were hypothesized to be negatively related to proportion of important support needs that are unmet.

Method

Participants

Seventy-three married couples of children or adolescents with ASD (aged 5 to 18 yrs) residing in a Midwestern state in the U.S. participated in the study. Participants were recruited through fliers mailed to families of children or adolescents who had received an educational label of ASD in schools and fliers posted on ASD listservs, ASD clinics, and community settings (e.g., libraries). The majority of the parents (n = 141) were the biological parent of the child/adolescent with ASD. However, 3 parents were stepparents and 2 parents were adoptive parents, all of whom had played an integral parenting role for the child or adolescent with ASD for at least 3 years. Documentation of ASD diagnosis by a medical or educational specialist was provided for all children/adolescents. This evaluation had to include administration of the Autism Diagnostic and Observational Schedule (Lord et al., 2000), on which all children and adolescents scored above the ‘autism spectrum’ cutoff. Moreover, all children/ adolescents meet or exceeded the ASD cutoff based on parent report on the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Rutter, Bailely, & Lord, 2003). Seven (9.6%) of the couples had more than one child with an ASD; one child was randomly selected as the target child. Table 1 presents family socio-demographic information.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Parents and Children/Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

| Parent | |

|---|---|

| Age in yrs (M[SD]) | 42.56 (6.35) |

| Range | 28-62 |

| Household income (Median [SD]) | $70-90K ($20K) |

| Range | <20K - >$180K |

| Education (n[%]) | |

| Less than high school degree | 2 (3.17%) |

| High school degree/GED | 15 (23.80%) |

| College degree | 31 (49.21%) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 15 (23.80%) |

| Race/ethnicity (n[%]) | |

| Caucasian, Non-Hispanic | 56 (88.89%) |

| Hispanic | 3 (4.76%) |

| African-American | 1 (1.59%) |

| Native American | 1 (1.59%) |

| Asian | 2 (3.17%) |

| Total Number of Children (M[SD]) | 1.58 (0.99) |

| Range | 1-4 |

| Child/Adolescent with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | |

|---|---|

| Age in yrs (M[SD]) | 11.89 (4.91) |

| Range | 3.24- 18.93 |

| Gender (n[%]) | 37 (63.7%) |

| Intellectual disability (n[%]) | 38 (46.03%) |

| Yes | 4 (6.35%) |

| ASD symptoms (M[SD]) | 17.51 (5.71) |

| Range | 6-37 |

| Co-occurring Behavior Problems(M[SD]) | 4.13 (3.12) |

| Range | 0-13.06 |

| Age of diagnosis in yrs (M[SD]) | 5.21 (3.65) |

Note. GED = General Education Development.

Procedure

Parents were interviewed and independently completed self-report measures during a 2.5 hour lab or home visit. Following this session, mothers and fathers independently completed a 10-day online daily diary in which they rated their child or adolescent with ASD's daily co-occurring behavior problems. Parents who did not have access to the internet completed the diary via an Ipod Touch.

Measures

Support Needs

A modified version of the Family Needs Questionnaire (FNQ; Kreutzer, Complair, & Waaland, 1998) was used to assess support needs. The measure, originally created to assess the needs of family members of individuals with traumatic brain injury, has been previously modified to assess the needs of children and adolescents with ASD and other developmental disabilities (Siklos & Kerns, 2006). The modified FNQ was found to have acceptable reliability and internal consistency in a sample of 56 parents of children and adolescents with ASD and 32 parents of children and adolescent with Down syndrome (Siklos & Kerns, 2006). In the 54-item questionnaire, parents rate the extent to which each need was perceived as important (not important/ slightly important/ important/ very important) and whether this need had been met (yes/ no/ partly). In the present analyses, we merged responses to reflect whether or not items were important (important/very important) or not important (not important/slightly important) and met (yes) or not met (no/partly). Items were then summed to create the number of important support needs score. The proportion of important support needs that are unmet score was the percentage of important needs reported to be unmet.

Child/Adolescents Socio-demographics

Parents reported on the child/adolescent with ASD's gender and date of birth. Gender was coded as male (0) and female (1). The child/adolescent's age was coded in years. ID status was assessed through review of medical or educational records; ID was considered if the child/adolescent had a medical diagnosis of ID and/or met criteria for ID based on IQ and adaptive behavior testing. ID status was coded as not present (0) or present (1). Specific hypotheses were not made about child/adolescent gender, but this variable was included in order to explore potential associations.

Family Socio-demographics

Parents reported on their gender (0 = male, 1 = female). They also reported on their education and household income. Parent education was coded as 0 (high school degree or GED), 1 (some college), 2 (college degree) and 3 (graduate or professional degree). Household income was coded 0 to 14, starting at less than $20,000 (0) and increasing by $10,000 intervals until $90,000-99,9999 (10) and then increasing by $20,000 intervals to $160,000+ (14). Parent also reported on their total number of children. Total number of children was included in analyses to control for differences in number of support needs based on the presence of siblings. Parent race/ethnicity was collected and is presented in Table 1. However, this variable was not examined in analyses due to limited diversity.

Number of ASD Symptoms

The SCQ is a parent questionnaire that includes 40 yes-no questions about the presence of deficits in social functioning and communication in the child or adolescent. The SCQ was found to have good reliability and validity (Rutter et al., 2006). The SCQ had adequate internal consistency in the present sample (Cronbach's alpha =.86).

Co-occurring Behavior Problems

Co-occurring behavior problems of children and adolescents with ASD was assessed through a 10-day daily diary in which mothers and fathers separately rated the frequency (present vs. absence) and severity (5 point scale) of their son or daughter's behavior problems using a modified version of the Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised (SIB-R; Bruininks, Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1996). The SIB-R was developed for individuals with developmental disabilities and assesses 8 types of behavior problems (Bruininks et al., 1996). In the present study, the SIB-R was completed daily. We multiplied the frequency score (i.e., number of behavior problems rated as present) by the severity score (i.e., summed severity for all behavior problems rated as present) on each day and then calculated the average of this across the 10 days. This modified SIB-R was shown to have good within- and between-person variability in mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD (Seltzer et al., 2010).

Data Analysis Plan

Interspouse correlations were conducted to examine the degree of correspondence in number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet in mothers and fathers. Paired sample t-tests were used to compare the number of important support needs, and proportion of important support needs that are unmet for mothers and fathers within married couples. Paired sample t-tests were also conducted to determine which items on the FNQ significantly differed between mothers and fathers within married couples in terms of whether or not the item was rated as important and rated as both important and unmet. An alpha of .01 was used to judge statistical significance when examining within-couple mother-father differences in the FNQ items given the large number of comparisons. An alpha of .05 was used to judge statistical significance in all other analyses.

Correlations were conducted to identify the child (child age, child gender, ID status, co-occurring behavior problems, number of ASD symptoms) and family factors (parent education, household income, total number of children) related to the number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet. Correlations were separately conducted for mothers and fathers. Due to the non-independence of data from married couples, a multilevel modeling approach was employed (Snijders & Bosker, 1999) using hierarchal linear modeling software (Bryk, Raudenbush, & Congdon, 1994), to examine the child and family factors related to number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet. This multilevel modeling approach allowed us to treat parents as being nested within couples and, thus, account for between- and within-couple variance in support needs. All family/child variables were included regardless of their correlation with outcomes in order to fully assess their impact on outcomes when controlling for all other variables. Level 1 variables included parent gender, parent education, and co-occurring behavior problems. Level 2 variables included child age, child gender, child ID status, total number of children, number of ASD symptoms, and household income. Effect coding was used for parent gender (mothers = −1, fathers = 1), but not other categorical variables. Child ID status and child gender were un-centered whereas all other variables were grand-mean centered. Level 1 slopes were constrained, and Level 1 intercepts and Level 2 slopes varied at random.

Results

The interspouse correlations for number of important support needs (r = .51, p <.01) and proportion of important support needs that are unmet (r = .42, p <.01) indicated moderate consistency across spouses. Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for the number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet. Paired samples t-test indicated that, within couples, mothers reported a significantly higher number of important support needs and a significantly higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than fathers.

Table 2.

Number of Important Support Needs and Proportion of Important Support Needs that are Unmet in Mothers and Fathers

| Mothers | Fathers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | Paired Sample t-test, P-value | |

| Number of Important Support Needs | 36.92 (8.05) | 32.92 (10.66) | 3.16, < .01 |

| Proportion of Important Support Needs that are Unmet | 18.50 (15.73) | 12.93 (14.23) | 2.82, .01 |

Number of Important Support Needs

Table 3 presents the percentage of mothers and fathers who endorsed each item on the FNQ as important and the percentage who endorsed each item as both important and unmet. Bolded percentages indicate the top 11 support needs most frequently endorsed by mothers as important and the top 11 support needs most frequently endorsed by fathers as important. Nine of the top 11 important support needs for mothers were also among the top 11 important support needs for fathers. These overlapping important support needs reflect: 1) family-wide impacts (spend time alone with spouse, spouse agrees on decisions; sibling's friends feel comfortable); 2) having true partnerships with professionals (questions answered honestly, information about treatments, actively involved in treatment), 3) education about ASD (be well-educated about my child's disorder in order to be an effective decision-maker), 4) individualized education plans (child's school to set up a specialized education plan); and 5) parent self-care (more sleep). Mothers’ other top 11 important support needs focused on qualities of professionals (doctors/dentists having experience with condition; shown respect by professionals), whereas fathers’ other top 11 important support needs related to the social development of the child or adolescent with ASD (social activities other than with family; child to have own friends).

Table 3.

| Item endorsed | Important (%) | Unmet, Important (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I need to..... | Fathers | Mothers | t-test, p value | Mothers | Fathers | t-test, p value |

| Have my questions answered honestly | 100% | 95.9% | 1.43, .26 | 10.14% | 4.1% | 1.76, .08 |

| Be well-educated about my child's disorder in order to be an effective decision-maker regarding the needs of my child | 98.6% | 90.4% | 2.55, .02 | 9.6% | 0.00% | 2.55, .01* |

| Be shown respect by the professionals working with my child | 97.3% | 82.2% | 3.78,<.01* | 4.1% | 1.4% | 0.58, .57 |

| For my children's friends to feel comfortable around my child | 95.9% | 83.6% | 2.39, .02 | 5.5% | 15.1% | 1.94, .06 |

| Have my spouse and me agree on decisions regarding our child | 94.5% | 94.5% | 0.45, .66 | 5.5% | 5.5% | 0.45, .66 |

| Have time to spend alone with my partner | 94.5% | 97.3% | 1.43, .16 | 27.4% | 27.4% | 0.00, 1.00 |

| Get enough rest or sleep | 94.5% | 83.6% | 1.43, .16 | 17.8% | 17.8% | 0.00, 1.00 |

| My child's school to set up a specialized education plan for my child | 94.5% | 90.4% | 1.65, .10 | 5.5% | 2.7% | 1.00, .32 |

| Be actively involved in my child's treatments and therapies | 93.2% | 83.6% | 1.76, .08 | 8.2% | 5.5% | 0.71, .48 |

| Have information regarding my child's therapeutic or educational process | 93.2% | 91.8% | 0.33, .74 | 4.1% | 5.5% | 0.38, .71 |

| My child's doctor and dentist to have experience working with children with the same disorder as my child | 93.2% | 82.2% | 2.85, .01* | 5.8% | 5.5% | 0.45, .66 |

| For my child to have social activities other than with his/her own parents and siblings | 91.8% | 86.3% | 1.76, .08 | 26.0% | 20.5% | 0.94, .35 |

| For the professionals working with my child to understand the needs of my child and my family | 91.8% | 87.7% | 1.27, .21 | 12.3% | 5.5% | 1.27, .21 |

| My child to have friends of his/her own | 89.0% | 89.0% | 00, 1.00 | 37.0% | 32.7% | 0.77, .44 |

| Be shown that my opinions are used in planning my child's treatment, therapies, or education | 89.0% | 79.5% | 1.43, .16 | 2.7% | 1.4% | −0.58, .57 |

| Have a professional to turn to for advice or services when my child needs help | 86.3% | 78.2% | 1.51, .14 | 13.7% | 4.1% | 1.94, .06 |

| My child to have a teachers’ aide with him/her at school who has knowledge about, or experience with, working with children who have same disorder as my child | 86.3% | 86.3% | 0.30, .77 | 8.2% | 4.1% | 1.14, .26 |

| Work with professionals that have expertise working with children who have same developmental disorder as my child | 86.3% | 76.7% | 1.92, .06 | 16.4% | 5.5% | 1.84, .07 |

| Individuals in my child's classroom or job to understand that my child cannot help his/her unusual behaviors and difficulties | 84.9% | 82.2% | 10.53, .60 | 11.0% | 13.7% | 0.28, .78 |

| Have time to spend alone with my other children | 83.6% | 74.0% | 2.25, .03 | 9.6% | 6.8% | 0.63, .53 |

| Information about special programs and services available to my child and family | 80.8% | 67.1% | 2.00, .05 | 23.3% | 4.1% | 3.64, <.01* |

| Spent time with my friends | 79.5% | 46.6% | 4.06,<.01* | 12.3% | 9.6% | 0.53, .60 |

| Have other family members understand my child's problem | 78.1% | 67.1% | 1.54, .13 | 5.5% | 6.8% | 0.33, .74 |

| Get a break from my responsibilities | 78.1% | 58.9% | 2.89, .01* | 17.8% | 15.1% | 0.47, .64 |

| Have my child's therapies continue outside of school | 76.7% | 68.5% | 1.35, .18 | 27.4% | 6.8% | 3.36, <.01* |

| Have the professionals working with my child to speak to me in terms that I can understand | 74.0% | 69.9% | 0.39, .70 | 9.6% | 4.1% | 1.27, .21 |

| Services continuously rather than only in times of crisis | 74.0% | 65.8% | 1.63, .11 | 11.0% | 5.5% | 1.27, .21 |

| Help from other family members in taking care of my child | 74.0% | 60.3% | 2.44, .02 | 13.7 | 4.1% | 1.94,.06 |

| Financial support (e.g., from government) in order to provide my child his/her therapies, treatment, and care | 65.8% | 67.1% | 0.50, .62 | 20.5% | 13.7% | 1.22, .23 |

| Have consistent behavioral therapy for my child | 65.8% | 63.0% | 0.69, .50 | 19.2% | 6.8% | 2.64, .01* |

| Weekend and evening activities for my child | 61.2% | 61.6% | 0.21, .84 | 19.2% | 12.3% | 1.52,.13 |

| Help in remaining hopeful about my child's future | 61.2% | 54.8% | 0.85, .40 | 20.5% | 15.1% | 0.85, .40 |

| Different professionals agree on the best way to help my child | 60.3% | 52.1% | 1.06, .29 | 4.1% | 4.1% | 0.00, 1.00 |

| Have consistent speech therapy for my child | 58.9% | 47.9% | 1.56, .13 | 13.7% | 8.2% | 1.27, .21 |

| Have consistent occupational therapy for my child | 57.5% | 50.7% | 1.35, .18 | 16.4% | 6.8% | 1.76, .08 |

| Respite care for my child | 57.5% | 54.8% | 0.00, 1.00 | 15.1% | 13.7% | 0.38, .71 |

| Have help with housework | 54.8% | 45.2% | 1.54, .13 | 19.2% | 5.5% | 2.60, .01* |

| Be shown what to do when my child is acting unusually or is displaying difficult behaviors | 53.4% | 57.5% | 0.16, .87 | 5.5% | 9.6% | −0.63, .53 |

| Discuss my feelings about my child with a parent who has a child with the same disorder | 53.4% | 28.8% | 3.10,<.01* | 17.8% | 4.1% | 2.60, .01* |

| Help dealing with my fears about my child's future | 53.4% | 45.2% | 1.31, .20 | 16.4% | 6.8% | 2.18, .03 |

| To be told why my child acts in ways that are different, difficult, or unusual | 52.1% | 46.6% | 1.03, .31 | 8.2% | 1.4% | 1.93, .06 |

| Have my child's friends understand his/her problems | 50.7% | 60.3% | 1.23, .20 | 1.4% | 9.6% | 1.14, .26 |

| Professionals to be discreet when talking about my child when he/she is in the room | 49.3% | 43.8% | 0.60, .55 | 4.1% | 2.7% | 0.45, .66 |

| Be told if I am making good decisions about my child | 47.9% | 43.8% | 1.00, .32 | 4.1% | 6.8% | 0.82, .42 |

| Have counseling for myself and my spouse/partner | 47.9% | 24.7% | 3.54,<.01* | 27.4% | 19.2% | 1.27, .18 |

| Be encouraged to ask for help | 39.7% | 38.4% | 0.54, .59 | 20.5% | 15.1% | 1.00, .32 |

| Have consistent physical therapy for my child | 39.7% | 37.0% | 0.62, .54 | 15.1% | 5.5% | 1.62. .11 |

| Be reassured that it is not uncommon to have negative feelings about my child's unusual behaviors | 37.0% | 38.4% | 0.00, 1.00 | 16.4% | 4.1% | 2.39, .02 |

| Have counseling for my other children | 35.6% | 26.0% | 1.47, .15 | 17.8% | 12.3% | 1.00, .32 |

| Take vacations by myself each year | 35.6% | 31.5% | 0.78, .44 | 19.2% | 16.4% | 0.47, .64 |

| Have help in deciding how much to let my child do by himself/herself | 35.6% | 45.2% | 1.23, .22 | 8.2% | 11.0% | 0.30, .77 |

| Go out for dinner with my family each week | 34.2% | 37.0% | 0.62, .54 | 16.4% | 16.4% | 0.00, 1.00 |

| Take family vacations each year | 28.8% | 38.4% | 2.89, .06 | 20.5% | 20.5% | 0.00, 1.00 |

Note.

P ≤.01.

Bolded percentages represent the Top 11 most frequently endorsed Important Support Needs and the Top 10 most frequently endorsed Unmet Important Support Needs.

Paired sample t-tests were conducted to identify within-couple mother-father differences in important support needs (Table 3). Mothers were significantly more likely than fathers to rate 6 of the 54 support needs as important. As compared to fathers, mothers were more likely to place importance on: 1) qualities of the professionals (professionals show respect, doctor and dentist to have experience working with children with same disorder); 2) respite from responsibilities (break from responsibilities; spent time with friends); 3) talking with other parents of children and adolescents with ASD (discuss feelings about child with a parent who has child with same disorder); and 4) counseling for self and partner (have counseling for myself and my partner).

Important Support Needs that are Unmet

Table 3 also presents the percentage of mothers and fathers who reported each support need as both important and unmet. The top 10 most frequent important support needs that are unmet for mothers and fathers are bolded in Table 3. Seven of top 10 important support needs that are unmet for mothers were also in the Top 10 for fathers. These overlapping important support needs that are unmet related to: 1) child's social functioning (child to have friends, child to have social activities with people out of family); 2) family-wide impacts (time to spend alone with partner, counseling for self or partner, family vacations); 3) Relationship with professionals (encouragement to ask for help); and 4) future planning (fears about child's future). In terms of the non-overlapping top 10 important support needs that are unmet, for mothers these items were child-focused (financial support for treatments, information about special programs and services, consistent child therapies). In contrast, the remaining top 10 important support needs that are unmet for fathers were parent-focused (getting sleep, going out to dinner with family, vacations by oneself).

Paired sample t-tests were conducted to identify within-couple mother-father differences in important support needs that are unmet (Table 3). Mothers were significantly more likely than fathers to report important support needs that are unmet related to: 1) being educated about ASD (be well-educated about my child's disorder in order to be effective decision-maker); 2) assistance with household (have help with housework); 3) talking to parents of children/adolescents with ASD (discussing my feelings about child with a parent who has child with same disorder); 4) access to child treatments (consistent behavioral therapy, have my child's therapies continue outside of school, and information about programs and services).

Child and Family Factors and Number of Important Support Needs

Table 4 presents the correlations between child and family factors and number of important support needs. For mothers and fathers there was a significant positive correlation between co-occurring behavior problems and number of important support needs. For mothers, there was a significant negative correlation between child age and number of important support needs. For fathers, there was a significant negative correlation between household income and number of important support needs. Parent education, child gender, child ASD symptoms, and child ID status were not significantly correlated with number of important support needs.

Table 4.

Correlations among parent, child/adolescent, and support need variables for mothers (above diagonal) and fathers (below diagonal)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Variables | ||||||||||

| 1. Education | --- | .18 | −.03 | −.07 | .27* | .01 | .07 | .04 | −.13 | −.30** |

| 2. Household Income | .27* | --- | −.03 | .07 | .18 | .06 | −.05 | .09 | −.01 | .01 |

| 3. Total number of children | −.22 | −.03 | --- | .04 | −.23* | −.04 | .10 | .01 | .03 | .19 |

| Child Variables | ||||||||||

| 4. Age | .12 | .07 | .04 | --- | .01 | −.06 | −.08 | −.30** | −.28* | −.06 |

| 5. Gender | .06 | .18 | −.23* | .01 | --- | −.11 | .02 | −.05 | −.09 | −.04 |

| 6. Intellectual Disability Status | −.09 | .06 | −.04 | −.06 | −.11 | --- | −.09 | .09 | −.14 | .11 |

| 7. ASD Symptoms | .10 | −.05 | .10 | −.08 | .02 | −.09 | --- | −.38** | .21 | −.03 |

| 8. Co-occurring Behavior Problems | .06 | .16 | −.05 | −.19 | −.10 | −.18 | .22* | --- | .40** | .16 |

| Support Needs | ||||||||||

| 9. Number of Important Needs | .10 | .25* | −.01 | −.21 | .16 | −.13 | .03 | .32** | --- | .42** |

| 10. Proportion of Important Support Needs that are Unmet | −.26* | .25* | .19 | −.04 | −.06 | .14 | .04 | .19 | .44** | --- |

Note.

P < .05

P ≤ .01.

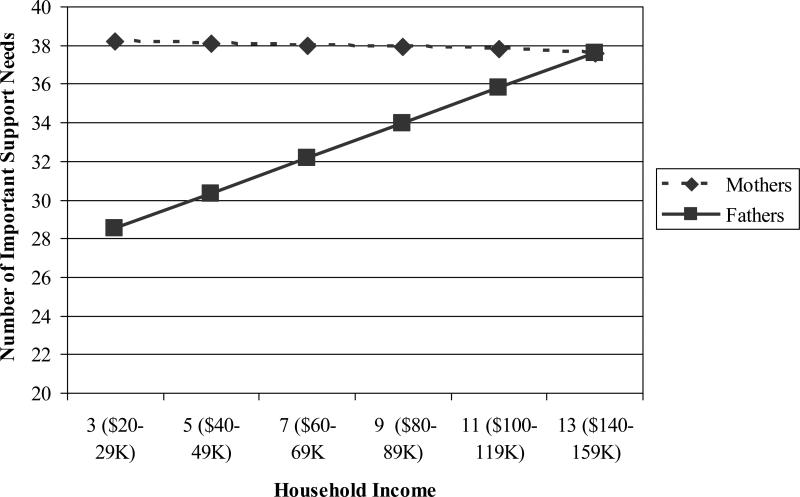

A multilevel model was conducted to understand the family and child factors related to number of important support needs. Parent gender was included to test for differences in effects between mothers and fathers. Table 5 presents findings from this model. There was not a significant effect of parent education, household income, child gender, child ID status, and child ASD symptoms. There was a significant effect of parent gender, child age, and child co-occurring behavior problems on number of important support needs. Consistent with our hypothesis, across couples, mothers reported a higher number of support needs than fathers. In support of our hypothesis, across couples, when other predictors were at their mean value, parents of younger children with ASD reported a higher number of important support needs than parents of older children with ASD. Also in support of our hypothesis, parents of children and adolescents with ASD with a higher co-occurring behavior problems reported a higher number of important support needs than parents of children and adolescents with ASD with lower co-occurring behavior problems. The potential moderating effect of parent gender on the child and family factors was then examined. There was a significant parent gender × household income effect. As shown in Figure 1, household income was not related to number of important support needs for mothers. In contrast, fathers with a lower household income reported a lower number of important support needs than fathers with a higher household income. There were no other significant parent gender moderating effects.

Table 5.

Multilevel Model Results for Number of Important Support Needs and Proportion of Important Support Needs that are Unmet

| Number of Important Support Needs | Proportion of Important Support Needs that are Unmet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Variables | Coefficient | SE | t-ratio | P value | Coefficient | SE | t-ratio | P value |

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| Intercept | 37.33 | 1.64 | 22.78 | <.001 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 20.90 | <.001 |

| Parent Gender (PG) | 1.58 | 0.53 | 2.96 | <.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.15 | .03 |

| Parent Education | −0.73 | 0.91 | −0.82 | .42 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.60 | .01 |

| Co-occurring Behavior Problems | 0.75 | 0.33 | 2.27 | <.01 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 2.15 | .03 |

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Household Income | 0.41 | 0.27 | 1.52 | .13 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.90 | 37 |

| Child Age | −0.39 | 0.18 | −2.07 | .04 | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.02 | .99 |

| Child Gender | 1.08 | 1.86 | 0.58 | .56 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.43 | .67 |

| Child Intellectual Disability Status | −2.92 | 1.83 | −1.59 | .12 | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.03 | .98 |

| Child ASD symptoms | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.14 | .89 | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.27 | .79 |

| Total Number of Children | 0.08 | 0.90 | 0.08 | .93 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.86 | .07 |

| PG × Household Income | −0.39 | 0.16 | −2.50 | .02 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| PG × Intellectual Disability Status | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.05 | 0.02 | −2.36 | .02 |

| Variance Components (SD) | ||||||||

| Intercept | 38.26 (6.19) χ2 = 175.06, P <.001 | 0.007 (0.09) χ2 = 134.86, P <.001 | ||||||

| Level 1 effect | 42.59 (6.53) | 0.01 (0.11) | ||||||

Note. * = P < .05; ** = P ≤ .01.

Figure 1.

Association between Household Income and Number of Important Support Needs for Mothers versus Fathers. Household income was coded 0 to 14, starting at less than $20,000 (0) and increasing by $10,000 intervals until $90,000-99,9999 (10) and then increasing by $20,000 intervals to $160,000+ (14).

Child and family Factors and Proportion of Important Support Needs that are Unmet

Table 4 also presents the correlations between child and family factors and proportion of important support needs that are unmet. For mothers and fathers there was a significant negative correlation between parent education and proportion of important support needs that are unmet. Household income, child age, child gender, child ASD symptoms, child co-occurring behavior problems, and child ID status were not significantly correlated with number of important support needs for mothers or fathers.

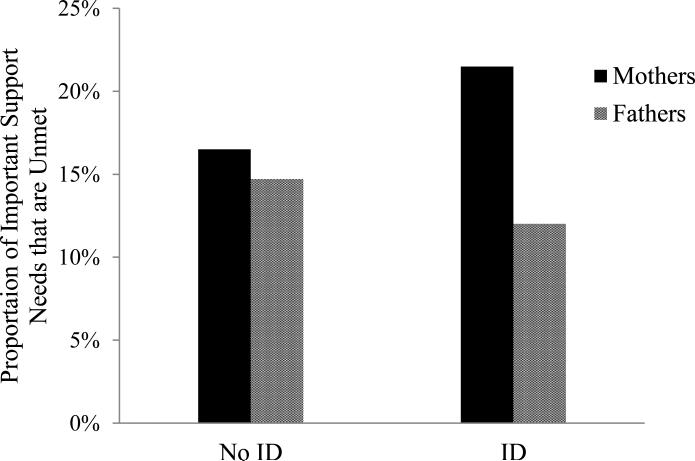

A multilevel model was conducted to identify the family and child factors related to proportion of important support need that are unmet. In the model, child age, household income, child gender, child ID status, and child ASD symptoms were not significantly related to proportion of important support needs that are unmet. There was a significant effect of parent gender, parent education, and child co-occurring behavior problems on proportion of important support needs that are unmet. In contrast to our hypothesis, across couples, mothers reported a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than fathers. In line with our hypothesis, across all couples, when the other predictors were at their mean value, parents with lower levels of education reported a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than parents with higher levels of education. Across couples, the child or adolescent with ASD's co-occurring behavior problems were positively associated with parents’ proportion of important support needs that are unmet. The potential moderating effect of parent gender × parent and child factors on proportion of important support needs that are unmet was then examined. There was a significant parent gender × child ID status cross-over effect. As shown in Figure 2, the presence of ID was associated with a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet (5% higher than no ID group) for mothers. In contrast, the presence of ID was associated with a slightly lower proportion of important support needs that are unmet (2.5% lower than no ID group) for fathers. There were no other significant parent gender moderating effects.

Figure 2.

Intellectual Disability (ID) Status coded as present (ID) versus not present (No ID) and Proportion of Important Support Needs that are Unmet for Mothers and Fathers.

Discussion

Children and adolescents with ASD exhibit a challenging profile of ASD symptoms, cognitive impairments, and co-occurring behavior problems. Parents of children and adolescents with ASD are at risk for poor psychological well-being as compared to parents of children without disabilities (Ekas & Whitman, 2010), as well as parents of children and adolescents with other types of disabilities (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Hartley et al., 2012). Understanding the important and unmet support needs of parents of children and adolescents with ASD is a critical first step towards better assisting parents, and subsequently, improving parent psychological well-being and family outcomes.

Within our sample, there was a moderate degree of concordance between mothers and fathers within married couples in the number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet. Thus, if one partner within a couple had a relatively high level of important and unmet support needs, so did their spouse. However, across couples, a pattern of mother-father differences emerged. Consistent with our hypothesis, mothers of children and adolescents with ASD endorsed a higher number of important support needs than fathers. Previous studies have similarly found that mothers of children and adolescents with chronic health conditions or other types of developmental disabilities report a higher number of support needs than do fathers (Bromely et al., 2004; Perrin et al, 2000). In part, mothers’ higher number of important support needs may reflect a greater role in childcare. Role specialization often occurs in families of children and adolescents with ASD, with mothers taking on the majority childcare (Dyer et al., 2009; Hartley et al., in press). As a result of their high level of childcare, mothers may be more aware of the support needs of the child or adolescent with ASD and may have more support needs of their own.

In contrast to our hypothesis, within couples, mothers reported a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than did fathers. Thus, despite the fact that current support services are not geared toward fathers, fathers were more likely to perceive that their support needs were met than were mothers within families of children and adolescents with ASD. This finding has implications for understanding mother-father discrepancies in psychological well-being. In previous studies of families of children and adolescents with ASD, mothers reported higher levels of parenting stress and more depressive symptoms than did fathers (e.g., Dabrowska & Pisula, 2010; Woodman et al., 2014). In part, the poorer outcomes of mothers may be due to their higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet. Father's lower level of unmet important support needs may also translate into less involvement in intervention services and therapies for their child or adolescent with ASD as compared to mothers, as is seen in the general population (e.g., Fabiano, 2007; Phares, Lopez, Frields, Kamboukos, & Duhig, 2005). Fathers may not be as motivated to participate in these interventions and services as compared to mothers as their needs are more likely to be met.

There was also a high level of concordance between mothers and fathers in terms of which support needs were perceived to be important. Nine of the top 11 important support needs in mothers were also in the top 11 important support needs in fathers. These overlapping support needs related to: family-wide impacts (support for marriage and siblings), developing partnerships with professionals, becoming educated on ASD, obtaining individualized education plans, and parent self-care. However, there were also mother-father differences in important support needs. Mothers’ other top 11 important support needs focused on qualities of professionals, whereas fathers’ other top 11 important support needs related to the social development of the child or adolescent with ASD. Within-couple comparisons similarly suggested that mothers were more likely than fathers to place importance on the qualities of professionals. Mothers’ greater emphasis on the qualities of professionals may be due to their greater involvement in child treatments and therapies, and thus more frequent interaction with professionals, as compared to fathers (Fabiano, 2007; Phares et al., 2005). In addition, mothers were more likely than fathers to place importance on respite from responsibilities, spending time with friends, and talking with parents of children/adolescents with ASD. Thus, mothers may be particularly likely to value to respite care and ASD parent support groups. In addition, mothers were more likely than fathers to view counseling for self and partner as important, which may reflect broader gender differences in openness to mental health services (Piko, 1998). Alternatively, mothers of children and adolescents with ASD may have a greater need for counseling given their higher levels of parenting stress as compared to fathers (Dabroswka & Pinula, 2010; Olsson & Hwant, 2001). In contrast, fathers emphasis on the child or adolescent with ASD's social development, suggests that supports for building social skills and opportunities for social activities should be at the forefront of treatment plans as well.

There was also a high level of agreement between mothers and fathers in important support needs that are unmet. Seven of top 10 important support needs that are unmet for mothers were also in the top 10 for fathers. These support needs related the child's social development, family-wide impacts, emotional support, and future planning. Many of these items were also endorsed as being important support needs that are unmet in a study using the FNQ in a British sample of parents of children and adolescents with ASD (Siklos & Kern, 2006).

In terms of mother-father differences in ratings of unmet important support needs, the remaining top 10 important support needs that are unmet were focused on child therapies and treatments for mothers and focused on parent self-care and relaxation for fathers. Within couple comparisons indicated mothers were also more likely than fathers to have important support needs that are unmet related to more access to child treatments and therapies, more ASD education, opportunities to talk with parents of children/adolescents with ASD, and help with housework. Overall, these findings suggest that fathers may benefit from increased opportunities for self-care and relaxation, whereas mothers may benefit from assistance with accessing child treatments and therapies, education about ASD, help with housework, and involvement in family support groups, as these needs are currently not being met. In addition to meeting these support needs through formal support services (e.g., involving professionals), increasing informal support through encouraging spouses to discuss differing support needs and finding ways to better support one another, may be a powerful intervention strategy. Increasing spousal communication about discrepancies in perspectives of support needs also has relevance for strengthening the marital relationship within families of children and adolescents with ASD.

Another aim of the study was to identify child and family factors related to number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet. In support of our hypothesis, child age was negatively related to number of important support needs, which may reflect that younger children often require more direct support needs than older children with ASD. We also found that parents of children and adolescents with ASD with a higher level of co-occurring behavior problems reported a higher number of important support needs and a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than parents of children and adolescents with ASD with a lower level of co-occurring behavior problems. Previous studies suggest that the child or adolescent with ASD's co-occurring behavior problems are more predictive of parent psychological well-being than the child/adolescent's level of cognitive impairment or severity of ASD symptoms (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Lecavalier et al., 2006). Given adverse impact of co-occurring behavior problems, it is not surprising that parents of children and adolescents with a higher level of co-occurring behavior problems have heightened support needs. Unfortunately, these needs are often not being met with the current service system. Our finding highlights the importance of considering co-occurring behavior problems, in addition to ASD symptoms and cognitive functioning, in support planning.

There was a parent gender cross-over effect of child ID status. The presence of ID was associated with a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet (5% higher than no ID group) for mothers, whereas it was associated with a slightly lower proportion of important support needs that are unmet (2.5% lower than no ID group) for fathers. The additional childcare responsibilities related to ID may largely fall on mothers; thus, mothers but not fathers may experience more support needs when the child or adolescent with ASD has ID.

Interestingly, fathers with a lower household income reported a lower number of important support needs than fathers with a higher household income. It may be that fathers with fewer financial resources are focused on basic and immediate support needs for the child or adolescent with ASD, and are less concerned with auxiliary support needs (i.e., nonessential treatments or qualities of professionals such as being shown respect). In support of our hypothesis, across couples, parents with lower levels of education reported a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than parents with higher levels of education. Parent education may influence the extent to which parents value formal support services. Moreover, the complexities of the educational and health service system, and unwelcoming professional practices, may discourage parents with less education from accessing supports.

There are strengths to the present study. Mother-father differences in support needs were examined at a within-couple level and using dyadic multilevel modeling to control for shared variance in family experiences. Parents separately rated the frequency and severity of child co-occurring behaviors on 10 consecutive days to avoid errors of retrospective reports and global ratings taken at one time point. There are also limitations to the present study. The sample size prevented detection of subtle mother-father differences in support needs. In addition, the sample was predominately White and of middle socio-economic status. This sample reflects population trends in ASD diagnosis; White children and children from high SES groups are significantly more likely to receive an ASD diagnosis than are black and Hispanic children (ADDMN, 2014), and children from low SES groups (Durkin et al., 2010). However, investigation of support needs in a racially/ethnically and economically diverse sample is needed in future studies. Finally, the present study did not investigate the potentially heightened or unique support needs of families of multiple children with ASD given the limited number of such families in the current sample and because the FNQ focused largely on the specific needs of the target child. However, this is an important question for future studies.

In summary, within a couple who has a child or adolescent with ASD, there is moderate agreement between spouses in terms of the family's important and unmet needs. However, on average, mothers reported a higher number of important support needs and had a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet than did fathers. Both mothers and fathers value support for family-wide impacts, developing partnerships with professionals, becoming educated on ASD, obtaining individualized education plans, and parent self-care. Unmet important needs were most commonly related to the child/adolescent with ASD's social development, family-wide impacts, emotional support, and future planning.

Mothers placed more importance on the qualities of professionals, respite from responsibilities, parent support groups, and counseling than did fathers within families of children and adolescents with ASD. In contrast, assistance with the child or adolescent with ASD's social development was particularly important for fathers. Fathers reported unmet important support needs related to self-care and time for relaxation, whereas mothers reported unmet important support needs related to accessing child treatments and therapies, education about ASD, help with housework, and involvement in family support groups. Child age and co-occurring behavior problems were associated with number of important support needs and proportion of important support needs that are unmet in both parents. The presence of ID was related to having a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet in mothers. Having a lower household income was related to a lower number of important support needs in fathers, whereas parents with more education reported a higher proportion of important support needs that are unmet. Overall, findings offer professionals insight into the overlapping and unique support needs of mothers and fathers of children and adolescents with ASD and the child and family characteristics related to important and unmet support needs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the University of Wisconsin Graduate School (to S. Hartley), National Institute on Mental Health (R01MH099190 to S. Hartley), and the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (P30 HD03352 to M. Seltzer).We would like to thank the families who participated in this study for their ongoing support.

Contributor Information

Sigan L. Hartley, Waisman Center and Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Wisconsin Madison

Haley M. Schultz, Waisman Center and Department of Rehabilitation Psychology, University of Wisconsin Madison

References

- Abbeduto L, Seltzer MM, Shattuck P, Wyngaarden Krauss M, Orsmond G, Murphy MM. Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, down syndrome, or fragile x syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2004;109(3):237–254. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<237:PWACIM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arango P. A parent's perspective on family-centered care. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1999;20(2):123–124. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199904000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 years – Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Blasco PM, Simeronsson RJ. Needs expressed by mothers and fathers of young children with disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1992;97:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brobst J, Clopton J, Hendrick S. Parenting children with autism spectrum disorders the couple's relationship. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2008;24:38–49. doi: 10.1177/1088357608323699. [Google Scholar]

- Bromely J, Hare DJ, Davidso K, Emerson E. Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders: Social support, mental health status, and satisfaction with services. Autism. 2004;8:409–423. doi: 10.1177/1362361304047224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruininks R, Woodcock R, Weatherman R, Hill B. Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised. Riverside; Chicago: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW, Congdon RT. HIM 2/3. Hierarchical Linear Modeling with the HLM/2L and HLM/3L Programs. Scientific Software International; Chicago: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cheak-Zamora NC, Yang X, Farmer JE, Clark M. Disparities in transition planning for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2013;131:447–454. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1572. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska A, Pisula E. Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2010;54:266–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01258x. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, Hamby DW. Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2007;13:370–378. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin MS, Maenner MJ, Meaney FJ, Levy SE, DiGuiseppi C, Nicholas JS. Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from a U.S. cross-sectional study. PLOS One. 2010;5:e11551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer WJ, McBride BA, Santos RM, Jeans LM. A longitudinal examination of father involvement with children with developmental delays. Does timing of diagnosis matter? Journal of Early Intervention. 2009;31:265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ekas NV, Whitman TL. Autism symptom topography and maternal socioemotional functioning. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2010;115:234–249. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-115.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA. Father participation in behavioral parent training for ADHD: Review and recommendations for increasing inclusion and engagement. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:683–693. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman RI, Boyer NC. The power to choose: Supports for families caring for individuals with developmental disabilities. Health and Social Work. 2000;5(1):59–68. doi: 10.1093/hsw/25.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DE. Gender and coping: The parents of children with high functioning autism. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00059-x. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00059-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, Floyd FJ, Orsmond GI, Greenberg JS, et al. Divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:449–457. doi: 10.1037/a0019847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Mihaila I, Bussanich PM, Otalora-Fadner H. Division of labor in families of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Family Relations. doi: 10.1111/fare.12093. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Schaidle EM, Burnson CF. Parental attributions for the behavior problems of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2013;34(9):651–660. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000437725.39459.a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Seltzer MM, Head L, Abbeduto L. Psychological well-being in fathers of adolescents and adults with Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, and Autism. Family Relations. 2012;61:327–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00693.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Sikora DS, McCoy R. Prevalence and risk factors of maladaptive behaviors in children with Autistic Disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2008;52:819–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton L, Rutter M. Adult outcomes for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantareas MM, Homatidis S. Assessing child symptom severity and stress in parents of autistic children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1989;30:459–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00259.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00259x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruetzer JS, Complair P, Waaland P. The family needs questionnaire. Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Medical College of Virginia; Richmond, VA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J. The impact of behavior problems on caregiving stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:172–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Orlando M, Yingling JT, Theurer-Kaufman KL, Mala DP, Tompkins LA. Satisfaction with primary health care received by families of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2006;20:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Stuart T, Auinger T. Health care utilization and expenditures for children with autism: Data from U.S. national samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:871–879. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0119-9. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Rutter M. The autism diagnostic observation schedule – generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin EC, Lewkowicz C, Young MH. Shared vision: Concordance among fathers, mothers, and pediatricians about unmet needs of children with chronic health conditions. Pediatrics. 2000;105:277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Lopez E, Frields S, Kamboukos D, Duhig AM. Are fathers involved in pediatric psychology research and treatment? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:631–643. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piko B. Social support and health in adolescence: A factor analytical study. British Journal of Health Psychology. 1998;3:333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. Social communication questionnaire. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Blumberg SJ, Rice C, Visser SN, Boyle C. The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatrics. 2007;119:114–121. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Gonzales V, Boulet SL, Visser SN, Rice CE, Van Naarden-Braun, Boyle CA. Concurrent medical conditions and health care use and needs among children with learning and behavioral developmental disabilities, National Health Interview Sruvey, 2006-2010. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;33:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Hong J, Smith LS, Almeida DM, Coe C, et al. Maternal cortisol levels and behavior problems in adolescents and adults with ASDs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:456–469. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0887-0. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0887-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siklos S, Kerns K. Assessing need for social support in parents of children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders. 2006;7(36):921–933. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff S, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;47:921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318179964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller M, Reyes N, Hotez E, Hutman T, Sigman M. Longitudinal change in the use of services in autism spectrum disorder: Understanding the role of child characteristics, family demographics, and parent cognitions. Autism. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1362361313476766. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Sage Publication; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- White N, Hastings R. Social and professional support for parents of adolescents with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2004;17:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman AC. Trajectories of stress among parents of children with disabilities: A dyadic analysis. Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2014;63(1):39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Woodside JM, Rosenbaum PL, King SM, King GA. Family-centered services: Developing and validating a self-assessment tool for pediatrics service providers. Children's Health Care. 2001;30(3):237–252. [Google Scholar]