Abstract

Background

An improved understanding of racial differences in the natural history, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of heart failure will have important clinical and public health implications. We assessed how clinical characteristics and outcomes vary across racial groups (whites, blacks, and Asians) in adults with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Methods

We identified all adults with HFpEF between 2005 and 2008 from four health systems in the Cardiovascular Research Network using hospital principal discharge and ambulatory visit diagnoses.

Results

Among 13,437 adults with confirmed HFpEF, 85.9% were white, 7.6% were black, and 6.5% were Asian. After adjustment for potential confounders and use of cardiovascular therapies, compared with whites, blacks (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.72, 95% CI: 0.62-0.85) and Asians (HR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.64-0.87) had lower risk of death from any cause. Compared with whites, blacks had a higher risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HR 1.48, 95% CI: 1.29-1.68); no difference was observed for Asians compared with whites (HR 1.01, 95% CI: 0.86-1.18). Compared with whites, no significant differences were detected in risk of hospitalization for any cause for blacks (HR 1.03, 95% CI: 0.95-1.12) and for Asians (HR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.85-1.02).

Conclusion

In a diverse population with HFpEF, we observed complex relationships between race and important clinical outcomes. More detailed studies of large populations are needed to fully characterize the epidemiologic picture and to elucidate potential pathophysiologic and treatment-response differences that may relate to race.

Keywords: Race, heart failure, preserved ejection fraction, mortality, hospitalization

INTRODUCTION

The burden of heart failure varies across different racial groups in the United States.1 and there are growing concerns about racial and ethnic disparities in the care of patients with heart failure.2 There is also an increased appreciation of the need to better understand racial differences in the natural history, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of heart failure.3

Heart failure represents a heterogeneous syndrome, with different classification schemes based on presumed etiology and contributing factors,4 but current treatment-based approaches to the care of heart failure patients have relied on stratifying by reduced versus preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Compared with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) has been particularly challenging and has largely focused on symptom management, as randomized trials of various therapeutic strategies have not demonstrated consistent benefits for survival or preventing hospitalization.Error! Bookmark not defined. Furthermore, very few population-based studies have been undertaken that have specifically focused on patients with HFpEF, and even less is known about the relation of race to outcomes in patients with this condition. White patients present with HFrEF and HFpEF in relatively equal proportions.5 However, recently published data from the Jackson Heart Study suggest that HFpEF may be the most common form of this clinical syndrome in blacks.6

In an effort to fill gaps in knowledge regarding clinical characteristics and outcomes for patients with HFpEF across different racial groups, we conducted a large population-based study within the Cardiovascular Research Network (CVRN).7,8

METHODS

Source population

The source population included members from four participating health plans within the CVRN, which was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.7 Sites included Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, and Fallon Community Health Plan in central Massachusetts. Participating sites provide care to an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse population across varying clinical practice settings and geographically diverse areas. Each site also has a Virtual Data Warehouse (VDW) which served as the primary data source for subject identification and characterization in the present study.8 The VDW is a distributed standardized data resource comprised of electronic datasets at each CVRN site, populated with linked demographic, administrative, ambulatory pharmacy, outpatient laboratory test results, and health care utilization (ambulatory visits and network and non-network hospitalizations with diagnoses and procedures) data for members receiving care at participating sites.

Institutional review boards at participating sites approved the study and waiver of consent was obtained due to the nature of the study.

Study sample and characterization of left ventricular systolic function

We first identified all persons aged ≥21 years with diagnosed heart failure based on either having been hospitalized with a principal discharge diagnosis of heart failure and/or having ≥3 ambulatory visits coded for heart failure with at least one visit being with a cardiologist between January 1, 2005 through December 31, 2008. We used the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition (ICD-9) codes to identify patients with heart failure: 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, 428.0, 428.1, 428.20, 428.21, 428.22, 428.23, 428.30, 428.31, 428.32, 428.33, 428.40, 428.41, 428.42, 428.43, and 428.9. Previous studies have shown a positive predictive value of >95% for admissions with a primary discharge diagnosis of heart failure based on these codes when compared against chart review and Framingham clinical criteria.9,10,11 For the outpatient definition, we required ≥3 ambulatory visits with associated heart failure diagnoses, with ≥1 of the visits to a cardiologist to enhance the specificity of this diagnosis.

We ascertained information on quantitative and/or qualitative assessments of left ventricular systolic function from the results of echocardiograms, radionuclide scintigraphy, other nuclear imaging modalities and left ventriculography test results available from site-specific databases complemented by manual chart review. We excluded all patients who had mild to severely reduced systolic function and focused only on the group with preserved systolic function. We defined preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) as either a reported left ventricular ejection fraction ≥50% and/or based on a physician’s qualitative assessment of preserved or normal systolic function.

Race categorization

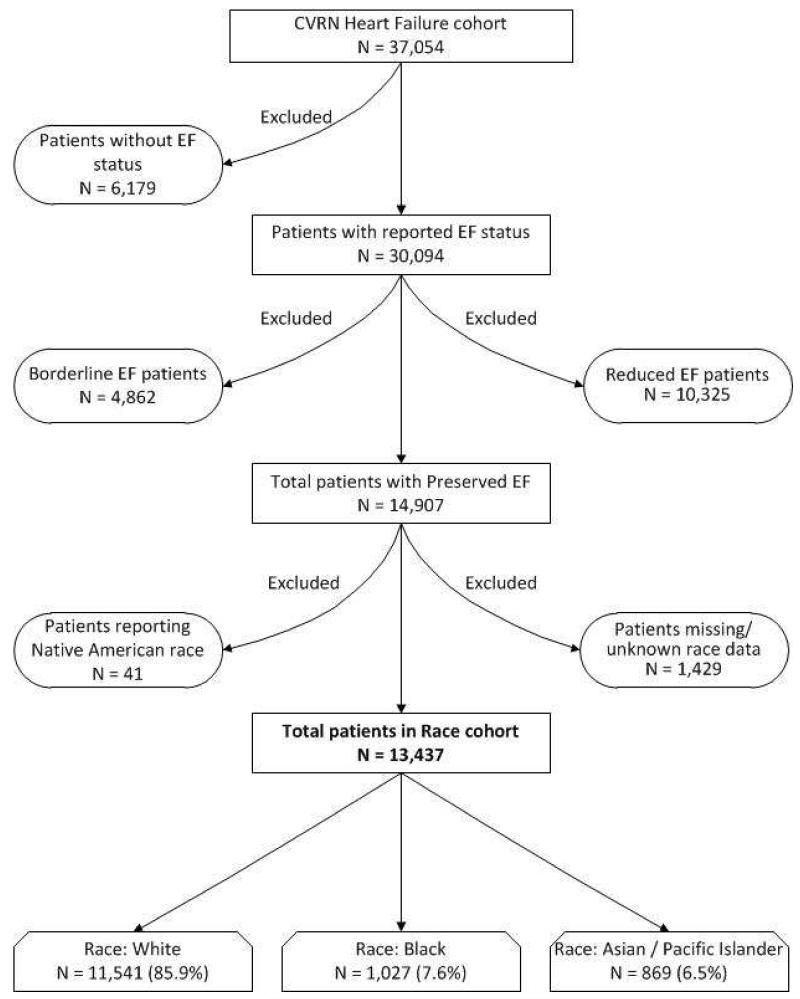

We classified patients based on their self-reported race information found in health system databases. We focused on patients classified as white, black or Asian. Patients with missing information on race were excluded from our study (Figure 1). We also excluded other race categories that made up less than 1% of the cohort population.

Figure 1. Cohort assembly diagram.

Follow-up and outcomes

Follow-up occurred from January 1, 2005 through December 31, 2008. Subjects were censored if they either disenrolled from the health plan or reached the end of study follow-up. Hospitalizations were identified from each site’s VDW, and admissions for heart failure were based on a principal discharge diagnosis for heart failure using the same inclusion criteria ICD-9 codes. Deaths were identified from hospital and billing claims databases, administrative health plan databases, state death certificate registries, and Social Security Administration files as available at each site. These approaches have yielded >97% vital status information in prior studies.9,10

Covariates

As previously described, we ascertained information on coexisting illnesses (based on diagnoses using relevant ICD-9 codes), laboratory results, and filled outpatient prescriptions from health plan hospitalization discharge, ambulatory visit, laboratory, and pharmacy databases, as well as site-specific diabetes mellitus and cancer registries.12 We defined prevalent heart failure as having any hospitalization or ambulatory heart failure diagnosis before the index date. We collected baseline information on the following: acute myocardial infarction; unstable angina; coronary artery revascularization; stroke or transient ischemic attack; atrial fibrillation or flutter; ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia; mitral or aortic valvular heart disease; peripheral arterial disease; rheumatic heart disease; receipt of a pacemaker; receipt of cardiac resynchronization therapy; receipt of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator; dyslipidemia; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; hospitalized bleed; diagnosed dementia; diagnosed depression; chronic lung disease; chronic liver disease; mechanical fall; and systemic cancer based on ICD-9 codes and CPT procedure codes. We also collected baseline and time-updated information on receipt of selected medications (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/aldosterone receptor blockers, aldosterone antagonists, anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, hydralazine, lipid lowering agents, loop diuretics, nitrates, and thiazide diuretics).

We ascertained available ambulatory results for baseline diastolic blood pressure, along with baseline and time-updated systolic blood pressure, serum LDL and HDL cholesterol levels, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and blood hemoglobin level.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (Cary, N.C.). We compared baseline characteristics across racial groups using analysis of variance, or the relevant non-parametric test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Given the large sample size, we focused only on differences in baseline characteristics that may be clinically meaningful.

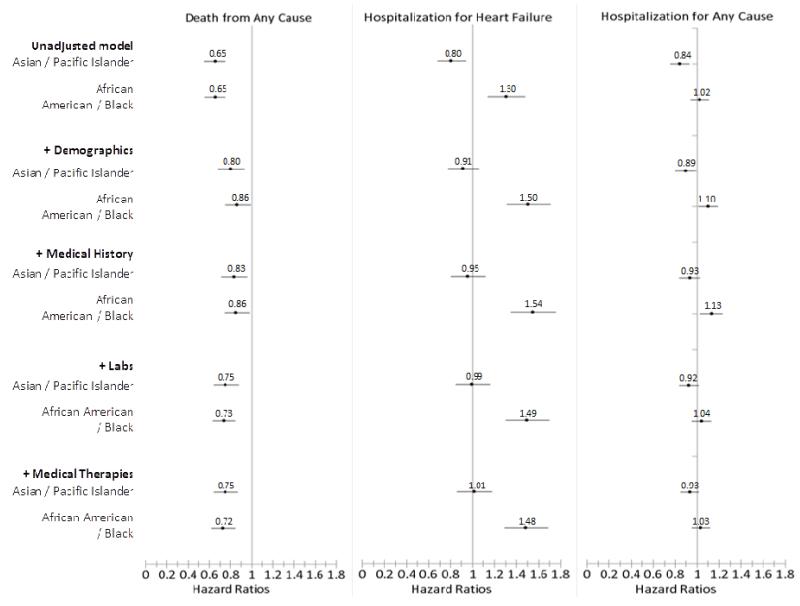

We calculated rates (per 100 person-years) for each outcome across the three racial groups (white, black, Asian). Next, we conducted exploratory analyses using multivariable extended Cox regression models with time-varying covariates to examine the independent association between the racial groups and the outcomes of interest (death, hospitalization for heart failure, and hospitalization for any cause). We explored 5 models for each outcome, starting with the unadjusted model, and adding on to each model in the following order: demographic data, medical history, laboratory test results, and medication use (Table 3 and Figure 2). Models were adjusted for age, gender, and any other variables at entry (Table 1) that differed across groups with a p value ≤0.10. In addition, we applied a robust sandwich estimator to account for clustering of multiple observations within the same subject and explored whether additional adjustment for clustering at the site level was necessary.

Table 3. Model results for outcomes of death from any cause, hospitalization for heart failure, and hospitalization for any cause.

| Race Categories | Death from Any Cause |

Hospitalization for Heart Failure |

Hospitalization for Any Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

|

| |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

| |||

| Black | 0.65 (0.56-0.75) | 1.30 (1.14-1.48) | 1.02 (0.94-1.11) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

0.65 (0.55-0.75) | 0.80 (0.68-0.94) | 0.84 (0.76-0.93) |

|

| |||

|

Adjusted for gender and age

Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|

| |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

| |||

| Black | 0.86 (0.75-0.99) | 1.50 (1.31-1.71) | 1.10 (1.01-1.19) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

0.80 (0.68-0.93) | 0.91 (0.78-1.06) | 0.89 (0.80-0.98) |

|

| |||

|

Adjusted for gender, age, and medical history

Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|

| |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

| |||

| Asian | 0.83 (0.71-0.97) | 0.95 (0.81-1.12) | 0.93 (0.84-1.03) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

0.86 (0.74-0.99) | 1.54 (1.35-1.76) | 1.13 (1.03-1.23) |

|

| |||

|

Adjusted for gender, age, medical history, and labs

Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|

| |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

| |||

| Black | 0.73 (0.63-0.85) | 1.49 (1.30-1.70) | 1.04 (0.95-1.13) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

0.75 (0.64-0.88) | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) | 0.92 (0.84-1.02) |

|

| |||

|

Adjusted for gender, age, medical history, labs, and medication

use Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|

| |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

| |||

| Black | 0.72 (0.62-0.85) | 1.48 (1.29-1.68) | 1.03 (0.95-1.12) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

0.75 (0.64-0.87) | 1.01 (0.86-1.18) | 0.93 (0.85-1.02) |

Figure 2. Hazard Ratios for outcomes of death from any cause, hospitalization for heart failure, and hospitalization for any cause, by race (reference group is white).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics among 13,437 patients with diagnosed heart failure and preserved left ventricular systolic function, stratified by race.

| Race |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall N = 13,437 |

White (Ref) N = 11,541 |

African American/ Black N = 1,027 |

Asian/ Pacific Islander N = 869 |

| Mean (SD) age, year | 75.9 (11.4) | 76.7 (10.9) | 69.9 (13.0)‡ | 72.4 (12.1)‡ |

| Age by categories, year | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Age <45 | 168 (1.3) | 101 (0.9) | 41 (4.0) | 26 (3.0) |

| Age 45-54 | 544 (4.0) | 379 (3.3) | 109 (10.6) | 56 (6.4) |

| Age 55-64 | 1531 (11.4) | 1215 (10.5) | 194 (18.9) | 122 (14.0) |

| Age 65-74 | 3181 (23.7) | 2627 (22.8) | 293 (28.5) | 261 (30.0) |

| Age 75-84 | 5129 (38.2) | 4549 (39.4) | 273 (26.6) | 307 (35.3) |

| Age 85+ | 2884 (21.5) | 2670 (23.1) | 117 (11.4) | 97 (11.2) |

| Female gender, n (%) | 7773 (57.8) | 6662 (57.7) | 654 (63.7) | 457 (52.6) |

| Medical History, n (%) | ||||

| Prevalent heart failure | 7823 (58.2) | 6782 (58.8) | 599 (58.3) | 442 (50.9)‡ |

| Acute myocardial Infraction | 1441 (10.7) | 1226 (10.6) | 100 (9.7) | 115 (13.2)* |

| Unstable angina | 924 (6.9) | 788 (6.8) | 70 (6.8) | 66 (7.6) |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | 820 (6.1) | 701 (6.1) | 40 (3.9)† | 79 (9.1)‡ |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 1153 (8.6) | 1009 (8.7) | 62 (6.0)† | 82 (9.4) |

| Ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack |

1170 (8.7) | 1005 (8.7) | 101 (9.8) | 64 (7.4) |

| Other thromboembolic event | 112 (0.8) | 93 (0.8) | 10 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 5830 (43.4) | 5264 (45.6) | 230 (22.4)‡ | 336 (38.7)‡ |

| Ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia | 225 (1.7) | 186 (1.6) | 26 (2.5)* | 13 (1.5) |

| Mitral and/or aortic valvular disease | 3672 (27.3) | 3322 (28.8) | 149 (14.5)‡ | 201 (23.1)‡ |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1224 (9.1) | 1080 (9.4) | 78 (7.6) | 66 (7.6) |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 362 (2.7) | 306 (2.7) | 18 (1.8) | 38 (4.4)† |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy | 14 (0.1) | 12 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 150 (1.1) | 135 (1.2) | 7 (0.7) | 8 (0.9) |

| Pacemaker | 892 (6.6) | 798 (6.9) | 38 (3.7)‡ | 56 (6.4) |

| Dyslipidemia | 8993 (66.9) | 7537 (65.3) | 772 (75.2)‡ | 684 (78.7)‡ |

| Hypertension | 11355 (84.5) | 9666 (83.8) | 927 (90.3)‡ | 762 (87.7)† |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3168 (23.6) | 2703 (23.4) | 256 (24.9) | 209 (24.1) |

| Hospitalized bleeds | 1031 (7.7) | 889 (7.7) | 84 (8.2) | 58 (6.7) |

| Diagnosed dementia | 1097 (8.2) | 965 (8.4) | 69 (6.7) | 63 (7.2) |

| Diagnosed depression | 2717 (20.2) | 2450 (21.2) | 162 (15.8)‡ | 105 (12.1)‡ |

| Chronic lung disease | 6005 (44.7) | 5306 (46.0) | 423 (41.2)† | 276 (31.8)‡ |

| Chronic liver disease | 553 (4.1) | 459 (4.0) | 52 (5.1) | 42 (4.8) |

| Mechanical fall | 557 (4.1) | 513 (4.4) | 15 (1.5)‡ | 29 (3.3) |

| Systemic cancer | 1152 (8.6) | 1022 (8.9) | 75 (7.3) | 55 (6.3)* |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73m2 |

‡ | ‡ | ||

| >130 | 16 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) | 8 (0.8) | 2 (0.2) |

| 90-130 | 1174 (8.7) | 933 (8.1) | 157 (15.3) | 84 (9.7) |

| 60-89 | 4531 (33.7) | 3952 (34.2) | 313 (30.5) | 266 (30.6) |

| 45-59 | 3172 (23.6) | 2784 (24.1) | 203 (19.8) | 185 (21.3) |

| 30-44 | 2572 (19.1) | 2298 (19.9) | 137 (13.3) | 137 (15.8) |

| 15-29 | 1158 (8.6) | 978 (8.5) | 93 (9.1) | 87 (10.0) |

| < 15 | 157 (1.2) | 110 (1.0) | 19 (1.9) | 28 (3.2) |

| Dialysis | 393 (2.9) | 242 (2.1) | 79 (7.7) | 72 (8.3) |

| Missing | 264 (2.0) | 238 (2.1) | 18 (1.8) | 8 (0.9) |

| Estimated hemoglobin, g/dL | ‡ | |||

| ≥16.0 | 519 (3.9) | 458 (4.0) | 24 (2.3) | 37 (4.3) |

| 15.0-15.9 | 962 (7.2) | 858 (7.4) | 46 (4.5) | 58 (6.7) |

| 14.0-14.9 | 1947 (14.5) | 1704 (14.8) | 120 (11.7) | 123 (14.2) |

| 13.0 - 13.9 | 2765 (20.6) | 2430 (21.1) | 157 (15.3) | 178 (20.5) |

| 12.0 - 12.9 | 2683 (20.0) | 2294 (19.9) | 214 (20.8) | 175 (20.1) |

| 11.0 - 11.9 | 2019 (15.0) | 1678 (14.5) | 195 (19.0) | 146 (16.8) |

| 10.0 - 10.9 | 1227 (9.1) | 1015 (8.8) | 129 (12.6) | 83 (9.6) |

| 9.0 - 9.9 | 549 (4.1) | 445 (3.9) | 76 (7.4) | 28 (3.2) |

| <9.0 | 225 (1.7) | 184 (1.6) | 31 (3.0) | 10 (1.2) |

| Missing | 541 (4.0) | 475 (4.1) | 35 (3.4) | 31 (3.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| ≥180 | 369 (2.7) | 285 (2.5) | 62 (6.0) | 22 (2.5) |

| 160-179 | 994 (7.4) | 787 (6.8) | 131 (12.8) | 76 (8.7) |

| 140-159 | 2597 (19.3) | 2195 (19.0) | 240 (23.4) | 162 (18.6) |

| 130-139 | 2680 (19.9) | 2280 (19.8) | 233 (22.7) | 167 (19.2) |

| 121-129 | 2051 (15.3) | 1758 (15.2) | 136 (13.2) | 157 (18.1) |

| 110-120 | 3265 (24.3) | 2841 (24.6) | 187 (18.2) | 237 (27.3) |

| 100-109 | 606 (4.5) | 558 (4.8) | 19 (1.9) | 29 (3.3) |

| <100 | 302 (2.2) | 276 (2.4) | 10 (1.0) | 16 (1.8) |

| Missing | 573 (4.3) | 561 (4.9) | 9 (0.9) | 3 (0.3) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| ≥110 | 63 (0.5) | 41 (0.4) | 19 (1.9) | 3 (0.3) |

| 100-109 | 192 (1.4) | 147 (1.3) | 31 (3.0) | 14 (1.6) |

| 90-99 | 602 (4.5) | 473 (4.1) | 88 (8.6) | 41 (4.7) |

| 85-89 | 568 (4.2) | 457 (4.0) | 71 (6.9) | 40 (4.6) |

| 81-84 | 842 (6.3) | 683 (5.9) | 105 (10.2) | 54 (6.2) |

| ≤80 | 10597 (78.9) | 9179 (79.5) | 704 (68.5) | 714 (82.2) |

| Missing | 573 (4.3) | 561 (4.9) | 9 (0.9) | 3 (0.3) |

| High density lipoprotein, mg/dL | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| ≥60 | 2417 (18.0) | 2025 (17.5) | 218 (21.2) | 174 (20.0) |

| 50-50.9 | 2420 (18.0) | 2033 (17.6) | 221 (21.5) | 166 (19.1) |

| 40-49.9 | 3653 (27.2) | 3088 (26.8) | 285 (27.8) | 280 (32.2) |

| 35-39.9 | 1805 (13.4) | 1596 (13.8) | 104 (10.1) | 105 (12.1) |

| <35 | 1889 (14.1) | 1684 (14.6) | 113 (11.0) | 92 (10.6) |

| Missing | 1253 (9.3) | 1115 (9.7) | 86 (8.4) | 52 (6.0) |

| Low density lipoprotein, mg/dL | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| ≥200 | 91 (0.7) | 63 (0.5) | 18 (1.8) | 10 (1.2) |

| 160-199.9 | 434 (3.2) | 361 (3.1) | 55 (5.4) | 18 (2.1) |

| 130-159.9 | 1234 (9.2) | 1052 (9.1) | 95 (9.3) | 87 (10.0) |

| 100-129.9 | 3020 (22.5) | 2597 (22.5) | 254 (24.7) | 169 (19.4) |

| 70-99.9 | 4851 (36.1) | 4171 (36.1) | 367 (35.7) | 313 (36.0) |

| <70 | 2457 (18.3) | 2100 (18.2) | 148 (14.4) | 209 (24.1) |

| Missing | 1350 (10.0) | 1197 (10.4) | 90 (8.8) | 63 (7.2) |

P-value of comparisons between white vs. one of the other races.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Among 13,437 adults identified with HFpEF, 85.9% were white, 7.6% were black and 6.5% were Asian (Table 1). The mean age of cohort members was 75.9 years, with 59.6% of the cohort aged ≥75 years, and 21.5% aged ≥85 years; 57.8% were women (Table 1). Blacks were more likely to be younger and less likely to have a history of atrial fibrillation and valvular disease than whites, while Asians were more likely to be older than blacks but younger than whites. Asians were less likely to have a history of atrial fibrillation and valvular disease compared with whites. However, both Asians and blacks were more likely to have a history of hypertension and dyslipidemia compared with whites.

Death from any cause by race

The median follow up time was 1.8 years (interquartile range 0.7 to 3.0 years). Overall, the rate of death from any cause was 14.5 per 100 person-years (95% confidence Interval [CI] 14.0-15.0). Crude rates per 100 person-years of death were lower among blacks (10.3 [95% CI: 8.9-11.7]) and Asians (10.6 [95% CI: 9.0-12.2]), compared with whites (15.2 [95% CI: 14.7-15.7]) (Table 2). After adjustment for age and gender, blacks (adjusted hazard ratio 0.86, 95% CI: 0.75-0.99) and Asians (adjusted hazard ratio 0.80, 95% CI: 0.68-0.93) had lower risk of death compared with whites (Table 3 and Figure 2). These associations persisted after additional adjustment for a wide range of comorbid conditions, laboratory results and longitudinal medication use, with protective associations for blacks (adjusted hazard ratio 0.72, 95% CI: 0.62-0.85) and Asians (adjusted hazard ratio 0.75, 95% CI: 0.64-0.87) in fully adjusted models (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Table 2. Crude rates for outcomes of death from any cause, hospitalization for heart failure, and hospitalization for any cause, stratified by race.

|

Death from Any Cause

| |

| Race category | Rate per 100 PY (95% CI) |

|

| |

| Overall | 14.5 (14.0, 15.0) |

| White | 15.2 (14.7, 15.7) |

| Black | 10.3 (8.9, 11.7) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 10.6 (9.0, 12.2) |

|

| |

|

Hospitalization for Heart Failure (HF)

| |

| Race category | Rate per 100 PY (95% CI) |

|

| |

| Overall | 22.0 (21.4, 22.6) |

| White | 21.3 (20.6, 21.9) |

| Black | 30.2 (27.8, 32.6) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 21.4 (19.2, 23.7) |

|

| |

|

Hospitalization for Any Cause

| |

| Race category | Rate per 100 PY (95% CI) |

|

| |

| Overall | 117.2 (115.9, 118.6) |

| White | 117.2 (115.7, 118.6) |

| Black | 123.8 (118.9, 128.6) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 109.5 (104.4, 114.7) |

Hospitalization for heart failure by race

Overall, the crude rate per 100 person-years of hospitalization for heart failure was 22.0 (95% CI: 21.4-22.6). Blacks had the highest crude rate (per 100 person-years) of hospitalization for heart failure (30.2 [95% CI: 27.8-32.6]), while crude rates for Asians (21.4 [95% CI: 19.2-23.7]) were similar to whites (21.3 [95% CI: 20.6-21.9]) (Table 2). Compared with whites, blacks were at higher risk of hospitalization for heart failure (hazard ratio = 1.30 [95%CI: 1.14-1.48]). Asians had a lower risk of hospitalization for heart failure, with a hazard ratio of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.68-0.94), compared with whites (Table 3 and Figure 2). After adjusting for age and gender, compared with whites, blacks’ risk of hospitalization for heart failure increased to a hazard ratio of 1.50 (95% CI: 1.31-1.71). However, Asians no longer evidenced a significant protective effect for hospitalization for heart failure (hazard ratio = 0.91 [95% CI: 0.78-1.06]), compared with whites (Table 3 and Figure 2). As adjustments were made for medical history, laboratory test results, and medication use, the risk of hospitalization for heart failure did not change substantially. After adjusting for all possible confounders, compared with whites, blacks had a higher risk of hospitalization for heart failure with a hazard ratio of 1.48 (95% CI: 1.29-1.68), whereas Asians were at similar risk of hospitalization for heart failure compared with whites, with a hazard ratio of 1.01 (95% CI: 0.86-1.18).

Hospitalization for any cause by race

Overall, the crude rate per 100 person-years of hospitalization for any cause was 117.2 (95% CI: 115.9-118.6). Blacks had the highest crude rate (per 100 person-years) of hospitalization for any cause (123.8 [95% CI: 118.9-128.6]), while the crude rate for Asians was lowest (109.5 [95% CI: 104.4-114.7]). The crude rate of hospitalization for any cause among whites was similar to the overall rate (117.2 [95% CI: 115.7-118.6]) (Table 2). In unadjusted analyses, there was no significant difference in risk between blacks and whites, with a hazard ratio of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.94-1.11). However, Asians had a lower risk of hospitalization for any cause compared with whites, with a hazard ratio of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.76-0.93) (Table 3 and Figure 2). After adjusting for age and gender, compared with whites, blacks had a slightly higher risk of hospitalization for any cause, with a hazard ratio of 1.10 (95% CI: 1.01-1.19). Asians had a slightly lower risk of hospitalization compared with whites with a hazard ratio of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.80-0.98). After further adjustment for medical history, blacks still had an increased risk of hospitalization compared with whites, with a hazard ratio of 1.13 (95% CI: 1.03-1.23). However, Asians no longer had a significantly lower risk of hospitalization compared with whites, with a hazard ratio of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.84-1.03) (Table 3 and Figure 2). With further adjustment for lab-based measures, both blacks and Asians were observed to have similar risk of hospitalization compared with whites, with a hazard ratio of 1.04 (95% CI: 0.95-1.13) and a hazard ratio 0.92 (95% CI: 0.84-1.02), respectively (Table 3 and Figure 2). After adjustment for all possible confounders, compared with whites, there were no significant differences in risk of hospitalization for any cause for blacks or Asians, with a hazard ratio of 1.03 (95% CI: 0.95-1.12) and a hazard ratio of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.85-1.02) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

In this large, multicenter cohort comprised of patients with HFpEF, important racial differences in outcomes were observed. After adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics, compared with whites, blacks and Asians had a lower risk for death. However, blacks had a higher risk of hospitalization for heart failure compared with both whites and Asians.

A lower risk of in-hospital death among black patients with heart failure compared with white heart failure patients has been noted in several prior studies,13,14,15,16 and a reduced risk of dying within a 12-month follow-up period for black patients discharged from the hospital with a heart failure diagnosis compared with white patients has also been reported (albeit based on data from the early 1990s).17 In addition, analyses of Medicare claims data from 1985 and through 2000 have indicated that black patients with a heart failure diagnosis had lower in-hospital mortality rates and better long-term survival than white patients.18,19 Data from the National Heart Failure Project, a nationwide sample of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with heart failure in 1998 and 1999, suggested that although black patients had a 9% higher risk of rehospitalization than white patients, they had a 22% lower adjusted risk of 30-day mortality.20 In contrast, analyses comparing subgroups of participants in several clinical trials of heart failure have reported no racial differences in outcome and treatment effects between black and white study participants after adjustment for baseline differences.21,22 However, none of these studies analyzed patients according to type of heart failure (e.g., HFrEF or HFpEF).

A recently published study employing data from the Get With The Guidelines-HF registry reported on racial differences in outcomes among patients aged 65 and older who had been discharged from the hospital with a diagnosis of heart failure between 2005 and 2011.23 After risk adjustment, blacks had a lower risk of death, but slightly higher risk of readmission compared with white patients. These analyses did not adjust for ejection fraction, and no analysis specific to HFpEF patients was conducted.

Few prior studies have examined outcomes by race according to left ventricular ejection fraction, and information relevant to racial differences in patients with HFpEF is very limited. Among patients with symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, data from a single site study of patients who had undergone diagnostic cardiac catheterization suggested no differences between blacks and whites in long-term survival overall, but a survival disadvantage for blacks who had a non-ischemic heart failure etiology relative to whites.24 In contrast, findings from Studies of Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction (SOLVD) prevention and treatment trials indicated that blacks had a higher risk of death from all causes.25

Data regarding Asian heart failure patients in comparison with white patients is even more limited than it is for black patients.26,27 While the care and outcomes of Asian-American patients with other cardiovascular conditions, such as acute myocardial infarction have been compared to whites,28 there is little information relating to heart failure. One study of residents of Alberta, Canada who were hospitalized with heart failure from 1999 through 2005, reported that Chinese patients had a significantly higher one-year mortality compared with white patients.29 Recently published data from the Get With The Guidelines-HF registry have suggested that Asian patients have similar risk of death and readmission compared with white patients.Error! Bookmark not defined.

Some authors have commented that a survival advantage for blacks compared with whites lacks a ready explanation.30 Others have suggested that an increased prevalence of comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension among black patients might lead to more frequent contact with health care providers who might then be able to address the earliest signs of cardiac decompensation.Error! Bookmark not defined. Furthermore, although hospitalization is routinely considered an adverse clinical outcome, and is even sometimes combined with mortality as a composite outcome,Error! Bookmark not defined. an alternative view might be to consider the hospital as a location where the best available care for a patient with symptomatic heart failure might have been provided, especially in the 1990’s and early 2000’s when most referenced studies were performed. It is important to emphasize that it is only over recent years that intensive efforts and systems of care to address the ongoing medical needs of patients with heart failure in the outpatient setting have been widely adopted.31,32,33

In conclusion, the issue of race and its relationship to the incidence, prevention, treatment, and outcomes of cardiovascular disease is neither simple nor straightforward. Many unanswered questions must be addressed to fully understand potential pathophysiologic and treatment-response differences between races.34 As Richard Gillum wrote nearly two decades ago in reference to cardiovascular disease in blacks,35 “more detailed studies of large populations, designed to permit analyses of subgroups based on age, sex, ethnic group, region of residence, degree of urbanization, and socioeconomic status, are needed in order to complete the epidemiologic picture, and permit more effective intervention to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.”

Clinical Significance.

After adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics, compared with whites, blacks and Asians with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) have a lower risk of death.

However, blacks have a higher risk of hospitalization for heart failure compared with both whites and Asians.

Race and its relationship to clinical outcomes in the care of patients with HFpEF is neither simple nor straightforward.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study was supported by 1RC1HL099395 and U19 HL91179 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. McManus was supported by KL2RR031981 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). The sponsors had no role in: the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

Authorship: All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Franciosa JA, Ferdinand KC, Yancy CW. Treatment of heart failure in African Americans: a consensus statement. Congest Heart Fail. 2010 Jan-Feb;16(1):27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2009.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterson E, Yancy CW. Eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in cardiac care. N Engl J Med. 2009;30:1172–1174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0810121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, Arynchyn A, Lewis CE, Williams OD, Hulley SB. Racial differences in heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1179–1190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurwitz JH, Magid DJ, Smith DH, et al. Contemporary prevalence and correlates of incident heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Med. 2013;126:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta DK, Shah AM, Castagno D, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in African-Americans- the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go AS, Magid DJ, Wells B, et al. The Cardiovascular Research Network: a new paradigm for cardiovascular quality and outcomes research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:138–147. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.801654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magid DJ, Gurwitz JH, Rumsfeld JS, Go AS. Creating a research data network for cardiovascular disease: the CVRN. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6:1043–1045. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.8.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Go AS, Lee WY, Yang J, Lo JC, Gurwitz JH. Statin therapy and risks for death and hospitalization in chronic heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296:2105–2111. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go AS, Yang J, Ackerson LM, et al. Hemoglobin level, chronic kidney disease, and the risks of death and hospitalization in adults with chronic heart failure: the Anemia in Chronic Heart Failure: Outcomes and Resource Utilization (ANCHOR) Study. Circulation. 2006;113:2713–2723. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1441–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen LA, Magid DJ, Gurwitz JH, Smith DH, Goldberg RJ, Saczynski J, Thorp ML, Hsu G, Sung SH, Go AS. Risk factors for adverse outcomes by left ventricular ejection fraction in a contemporary heart failure population. Circulation. Heart failure. 2013;6(4):635–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philbin EF, DiSalvo TG. Influence of race and gender on care process, resource use, and hospital-based outcomes in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:76–81. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas KL, Hernandez AF, Dai D, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with clinical risk factors, quality of care, and acute outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2011;161:746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yancy CW, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Quality of care of and outcomes for African Americans hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the OPTIMIZE-HF (Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1675–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamath SA, Drazner MH, Wynne J, Fonarow GC, Yancy CW. Characteristics and outcomes in African American patients with decompensated heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1152–1158. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander M, Grumbach K, Remy L, Rowell R, Massie BM. Congestive heart failure hospitalizations and survival in California: patterns according to race/ethnicity. Am Heart J. 1999;137:919–927. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croft JB, Giles WH, Pollard RA, et al. Heart failure survival among older adults in the United States: a poor prognosis for an emerging epidemic in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:505–510. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown DW, Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Racial and ethnic differences in hospitalization for heart failure among elderly adults: Medicare, 1990 to 2000. Am Heart J. 2005;150:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rathore SS, Foody JM, Wang Y, et al. Race, quality of care, and outcomes of elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2003;289:2517–2524. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Echols MR, Felker GM, Thomas KL, et al. Racial differences in the characteristics of patients admitted for acute decompensated heart failure and their relation to outcomes: results from the OPTIME-CHF trial. J Card Fail. 2006;12:684–688. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathew J, Wittes J, McSherry F, et al. Racial differences in outcome and treatment effect in congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150:968–976. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vivo RP, Krim SR, Liang L, et al. Short- and long-term rehospitalizatoin and mortality for heart failure in 4 racial/ethnic populations. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001134. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001134. doi: 10.1161/JHA. 114.001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas KL, East MA, Velazquez EJ, et al. Outcomes by race and etiology of patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:956–963. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dries DL, Exner DV, Gersh BJ, Cooper HA, Carson PE, Domansi MJ. Racial differences in the outcome of left ventricular dysfunction. New Engl J Med. 1999;340:609–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palaniappan LP, Araneta MR, Assimes TL, et al. Call to action: cardiovascular disease in Asian Americans: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:1242–1252. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f22af4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh C. A national health agenda for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. JAMA. 2010;304:1381–1382. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian F, Ling FS, Deedwaania P, et al. Care and outcomes of Asian-American acute myocardial infarction patients: findings from the American Heart Association Get with the Guidelines-Coronary Artery Disease program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:126–133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaul P, McAlister FA, Ezekowitz JA, Grover VK, Quan H. Ethnic differences in 1-year mortality among patients hospitalized with heart failure. Heart. 2011;97:1048–1053. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.217869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jha AK, Shlipak MG, Hosmer W, Frances CD, Browner WS. Racial differences in mortality among men hospitalized in the Veterans Affairs health care system. JAMA. 2001;285:297–303. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303:1716–1722. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feltner C, Jones CD, Cene CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:774–84. doi: 10.7326/M14-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw RJ, McDuffie JR, Hendrix CC, et al. Effects of nurse-managed protocols in the outpatient management of adults with chronic conditions. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:113–121. doi: 10.7326/M13-2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor AL, Wright JT. Should ethnicity serve as the basis for clinical trial design? Importance of race/ethnicity in clinical trials: lessons from the African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT), the African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK), and Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Circulation. 2005;112:3654–3666. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillum RF. The epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in black Americans. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1597–1599. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611213352110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]