Abstract

Cellax, a polymer-docetaxel (DTX) conjugate that self-assembled into 120 nm particles, displayed significant enhancements in safety and efficacy over native DTX across a number of primary and metastatic tumor models. Despite these exciting preclinical data, the underlying mechanism of delivery of Cellax remains elusive. Herein, we demonstrated that serum albumin efficiently adsorbed onto the Cellax particles with a 4-fold increased avidity compared to native DTX, and the uptake of Cellax by cells was primarily driven by an albumin and SPARC secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine, an albumin binder) dependent internalization mechanism. In the SPARC-positive cells, a >2-fold increase in cellular internalization of Cellax was observed in the presence of albumin. In the SPARC-negative cells, no difference in Cellax internalization was observed in the presence or absence of albumin. Evaluation of the internalization mechanism using endocytotic inhibitors revealed that Cellax was internalized predominantly via a clathrin-mediated endocytotic mechanism. Upon internalization, it was demonstrated that Cellax was entrapped within the endo-lysosomal and autophagosomal compartments. Analysis of the tumor SPARC level with tumor growth inhibition of Cellax in a panel of tumor models revealed a positive and linear correlation (R2>0.9). Thus, this albumin and SPARC-dependent pathway for Cellax delivery to tumors was confirmed both in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Cellax, docetaxel, nanoparticle uptake, albumin, SPARC

INTRODUCTION

Despite the recent exciting advances in the field of nanomedicine, a fundamental understanding of the mechanism of delivery for nanomaterials within biological tissues remains elusive, largely due to a lack of mechanistic knowledge at the molecular level. Understanding the drug delivery mechanism is critical for identifying a biomarker for predicting the efficacy of nanoparticles, which could lead to improved stratification of patients for an increased success rate of therapy. It has been suggested that the unsatisfactory clinical success rate of nanomedicines is largely attributed to the lack of a strategy to identify patients that will show a response [1]. Therefore, investigating the mechanism of action for nanomedicines is of importance to enhance their therapy.

Cellax is a polymer-based nanoparticle drug delivery system, targeting docetaxel (DTX) to solid tumors. In preclinical evaluations, Cellax has demonstrated superior safety and efficacy compared to the approved taxane therapeutics including native DTX and Nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane) [2–8]. Cellax increases systemic drug exposure by 40-fold, improves the tumor delivery by >5.5-fold and enhances the specificity of biodistribution to the tumor [8]. Previous data have demonstrated that Cellax is efficiently internalized by cells in the tumor even without surface decoration with a targeting ligand [2].

In addition to surface modification with a ligand, it has been demonstrated that serum protein adsorption on the nanoparticle surface significantly affects the cellular internalization mechanism and tissue selectivity [9, 10], which in turn determines bioavailability, drug release site, pharmacokinetics and the efficacy of nanoparticles [11, 12]. Based on preliminary evaluations and the information derived from the literature [9, 13], it was hypothesized that after intravenous administration Cellax efficiently adsorbs serum proteins onto its surface, which in turn recognize tumor cells or mediate trapping of Cellax in the tumor microenvironment, eventually leading to cellular internalization. This study was aimed at testing this hypothesis, identifying key molecules triggering cellular internalization of Cellax, and providing the rationale for selecting a potential predictive biomarker for Cellax efficacy.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Materials

Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) sodium salt 30000-P was purchased from CPKelco (Atlanta, GA). Docetaxel (DTX) was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). Polyethylene glycol methyl ether (mPEG-OH, MW=2000), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide HCl (EDC.HCl), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Oakville, ON). DiI (1,10-dioctadecyl-3,3,3030-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate, D-307) was purchased from Invitrogen (Burlington, ON). Abraxane (Nab-PTX) was purchased from the University Health Network (UHN) pharmacy. Amiloride, Chlorpromazine, and Acetazolamide were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Oakville, ON). Anti LC3 (Rabbit) and anti Rab-7 (Rabbit) primary antibody as well as Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated anti rabbit (Goat) secondary antibody was purchased from Abcam Inc., Cambridge.

Synthesis, Preparation and Characterization of Cellax Nanoparticles

The Cellax polymer was synthesized by a method described previously [2–4, 8]. Briefly, the hydroxyl groups on carboxymethylcellulose (MW 275K) were acetylated (CMC-Ac), followed by EDC coupling of mPEG2000 and DTX to the remaining carboxyl groups of CMC-Ac. The acetylation of CMC rendered the polymer solvent-soluble and suppressed gelling properties, leading to enhanced drug-coupling efficiency and particle stability. The crude product was precipitated in ether to remove free DTX and was washed with water to remove free PEG. Gel permeation chromatography confirmed purity. Nanoparticles were produced by slow addition of an acetonitrile solution of Cellax polymer into an aqueous phase under vigorous vortex, followed by dialysis to remove the solvent and 0.22 µm sterile filtration. Concentration of DTX was measured by 1H NMR with a water pre-saturation protocol using 2-methyl-5-nitrobenzoic acid (1 mg/mL) as an internal standard (IS). A DTX/IS response factor was generated using a DTX (1 mg/mL) solution containing the IS. Cellax particles containing DiI (Cellax-DiI) were prepared and characterized as reported previously [2–4, 8]. Briefly, Cellax polymer (10 mg) was dissolved in MeCN (1 mL) containing 0.1 mg/mL DiI (1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3'3'-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate) and was precipitated into saline with aggressive vortexing to form nanoparticles. The DiI content was determined by dissolving Cellax-DiI in DMSO and measuring the fluorescence (Excitation: 535 nm; Emission: 590 nm) in the sample against a standard calibration curve of fluorescence versus DiI concentration, subtracting the background signal of the unloaded Cellax particle.

Cell Culture and Animal Models

EMT6, LL/2, PC-3, MDA-MB-231, B16F10, and 4T1 cells were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were grown in T75 flasks in a humid incubator maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. All experimental protocols in this study were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University Health Network (UHN, Toronto, ON, Canada) in accordance with the policies established in the Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals prepared by the Canadian Council of Animal Care. When tumor-bearing mice reached humane endpoints such as weight loss >20 wt%, tumor volume >1000 mm3, symptoms of significant discomfort (severe piloerection and withdrawn behaviour) or other physical issue (paralysis, morbidity, seizures) they were sacrificed and tissues were harvested for histological analysis.

Cellax Binding to Plasma Proteins

As there was no active targeting ligand conjugated to the surface of the Cellax nanoparticles, it was speculated that plasma protein binding to the particles might induce Cellax internalization by cells. Cellax nanoparticles (60 mg polymer/mL in saline) were incubated with 100 µL mouse plasma at 37°C for 1 h. Cellax was then separated from unbound proteins by centrifuging at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed with saline three times and resuspended in SDS buffer to a final concentration of 5 mg polymer/mL. Samples were then heated to 90°C to desorb the bound serum proteins. The proteins were subsequently separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was run at a constant voltage of 200 V for 35 min, and stained with Sypro Ruby protein stains. The protein bands were excised and analyzed by LC-MS/MS on a HPLC coupled to a mass spectrometer equipped with a nanoelectorspray ion source. The mass spectra were analyzed and referenced against a known database using Protein Pilot 2.0.1.

RT-PCR Evaluation of mRNA Expression of SPARC in a Panel of Cancer Cells

The expression of the SPARC [Homo sapiens secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich (osteonectin) (SPARC), NM_003118, Mus musculus secreted acidic cysteine rich glycoprotein (Sparc), NM_009242.4] was confirmed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. LL/2, EMT6, B16F10, PAN02, MDA-MB-231, 4T1, and PC3 cells (1 × 106 cells) were seeded in 6 well plates. After 24 h, the medium was removed and the cells were washed three times with PBS and harvested. Total RNA was prepared with RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen), and complementary DNA (cDNA) was reverse-transcribed with a QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). PCR primer sequences were as follows: SPARC, 5′-GTGCAGAGGAAACCGAAGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGTGGCAGGAAGAGTCGAA-3′ (reverse); Sparc, 5′-TTCAGACCGCCAGAACTCTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CACGGTTTCCTCCTCCACTA-3′ (reverse). cDNA from cells was amplified with specific primers with a SYBR Green Core Reagent Kit (Qiagen) and a real-time PCR instrument (Eppendorf). The expressions of mRNA of the target genes were evaluated by the efficiency-corrected ΔCT method [quantity = (efficiency + 1) − CT] as described previously [14].

Evaluation of the Role of Albumin and SPARC on the Cellax Internalization Mechanism

Cellax-DiI uptake was evaluated in 4T1 (SPARC+) and MDA-MB-231 (SPARC−) cells in the absence and presence of albumin [(40 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA)] containing media. Cells were adjusted to 1×105 cell/mL, and 1 mL of cell suspension was added to a 24-well plate containing sterile glass cover slips. After 12 h of incubation, media in each well was aspirated, and replaced with media containing Cellax-DiI (0.5 µg DiI/mL). The cell cultures were incubated at 37°C for 0.5 h, after which the media was aspirated, and cells were fixed with 500 µL of methanol for 1 min. The methanol was aspirated, the wells were washed twice with PBS, and 500 µL of 0.5 µg/mL DAPI solution was added. After 5 min, the DAPI solution was aspirated, and the slips were rinsed twice with PBS. The cover slips were mounted on glass slides with glycerol/PBS (95:5), and imaged on an Olympus Fluoview confocal microscope at 40× objective + 5× zoom. The intensity of the DiI and DAPI signal was measured using ImageScope software with positive pixel count algorithm (AOMF, Toronto, ON).

Flow Cytometry

EMT6 (SPARC+) and MDA-MB 231 (SPARC−) cells were used to confirm SPARC-and albumin-mediated cellular uptake. EMT6 and MDA-MB-231 cells (5 × 105) were seeded in a 6-well plate for 24 h at 37°C in the presence or absence of 40 mg/mL BSA (Sigma Aldrich, Oakville, ON). Cellax-DiI (25 mL, 300 µg DiI/mL content) was introduced to each well and incubated for 2 h. The cells were washed 3 times with PBS and were trypsinized. Cells were analyzed on a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Evaluation of the Pathway of Cellular Internalization for Cellax Nanoparticles

The internalization pathway of Cellax-DiI was evaluated using several endocytotic inhibitors including chlorpromazine (inhibits clathrin mediated endocytosis), amiloride (inhibits micropinocytosis) and filipin III (inhibits caveolae formation) using a method described in detail elsewhere with minor modifications [8]. Briefly, EMT6 cells were cultured onto a 24-well plate as described above. The cells were subsequently treated for 1 h at 37°C with chlorpromazine (10 µg/mL), amiloride (50 µM), filipin III (1 µg/mL), and concurrent treatments with chlorpromazine and amiloride to assess combination effects. The media was aspirated and replaced with media containing Cellax-DiI and allowed to incubate for an additional hour. The cells were stained with DAPI, fixed and imaged as described above. The intensity of the DiI signal within the cells was measured using ImageScope software and expressed as a ratio relative to control (cells treated with only Cellax-DiI) (AOMF, Toronto, ON).

Intracellular Fate

Building upon the previous study, it was believed that lysosomes play an integral role in the uptake of Cellax nanoparticles. Using LysoTracker Green, colocalization of Cellax-DiI within lysosomes was evaluated. Briefly, EMT6 cells were treated with Cellax-DiI for 4 h at 37°C. The media was aspirated and treated with LysoTracker Green (0.02 µg/mL) for 1.5 h at 37°C following the supplier's protocol. The cells were rapidly washed with ice cold PBS to prevent the removal of the attached LysoTracker Green, fixed and imaged using the method described above.

To understand the role of autophagy in the uptake process, we treated the EMT6 cells, plated on sterile glass cover slips, with Cellax-DiI for 24 h. The cells were then repeatedly washed with ice cold PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Then the cells were labelled with anti-LC3 antibody for 2 h at room temperature. It was stained with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody and imaged using the method described above.

To elucidate whether the internalized Cellax nanoparticles were localized in the endosome, we labelled the Cellax-DiI treated (treatment for 24 h) EMT6 cells with anti Rab-7 antibody after fixing and permeabilization. They were stained with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody and imaged using the method described above.

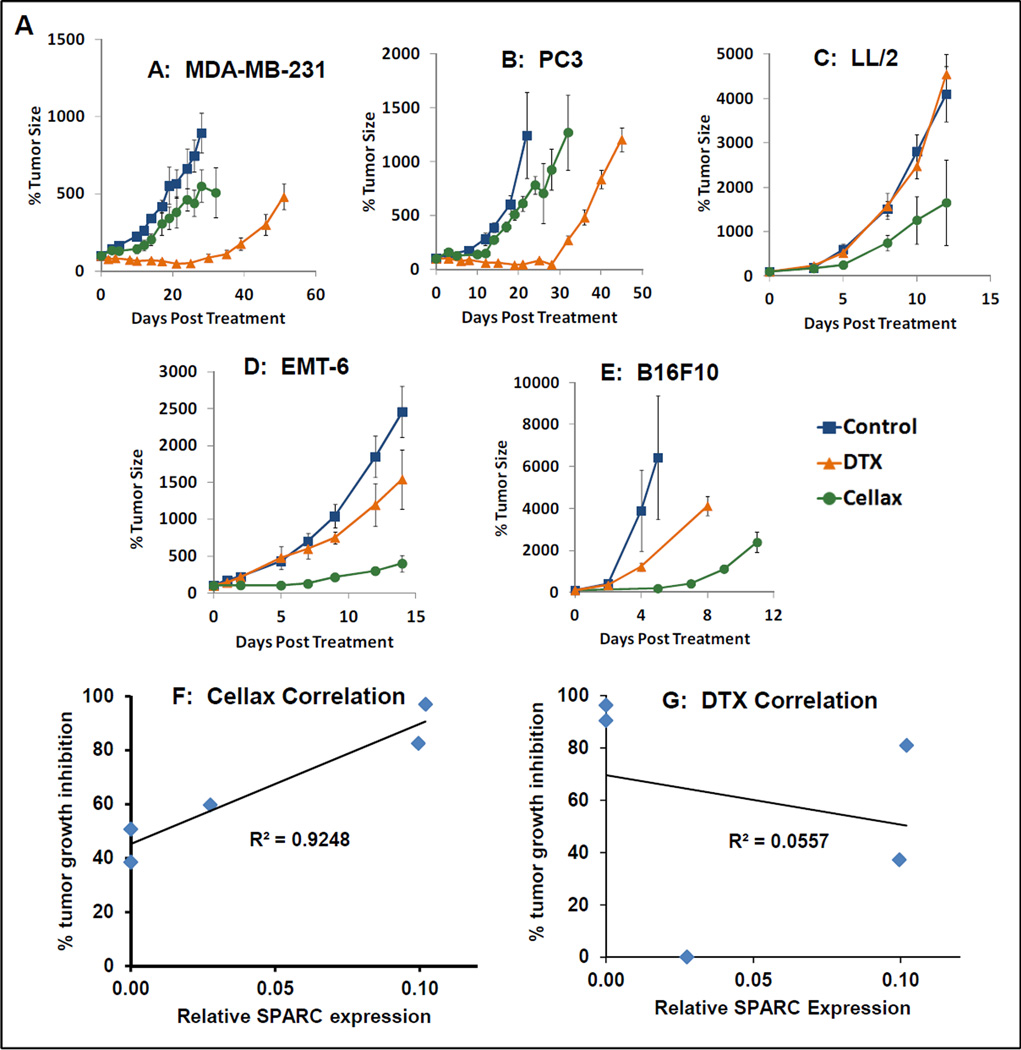

Evaluation of Tumor Growth Inhibition of Cellax and Native DTX in Tumor Models with Varying SPARC Expression

Mice were inoculated with subcutaneous tumors as previously published [1, 3–6]. When tumors were palpable, groups of mice were treated with a single i.v. dose of either Cellax (40 mg DTX/kg), native DTX (40 mg DTX/kg), or saline control. Tumor growth inhibition and body weight were monitored over time. The correlation between tumor growth inhibition was evaluated against the expression of SPARC.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Statistical analysis was conducted with the two-tailed unpaired t test for two-group comparison or one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey multiple comparison test for three or more groups (GraphPad Prism). Values of p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Physicochemical Characterization of Cellax

Characterization of the Cellax polymer and nanoparticles conformed to previous reports. Briefly, 1H-NMR indicates that the Cellax polymer contained 37.3 ± 1.5 wt% DTX and 4.7 ± 0.8 wt% PEG. In aqueous environments, Cellax polymer condenses to form nanoparticles of approximately 120 nm in diameter with a zeta potential of −8.1 ± 0.9 mV. Nanoparticles exhibited good thermodynamic and kinetic stability characterized by a slow, controlled drug release rate in serum (~5%/day).

We hypothesized that Cellax particles are internalized by cells via selective cellular recognition of serum/plasma proteins adsorbed onto the particles. To test this hypothesis, we first identified serum/plasma proteins that bound to the Cellax nanoparticles.

Plasma Protein Binding to Cellax Nanoparticles

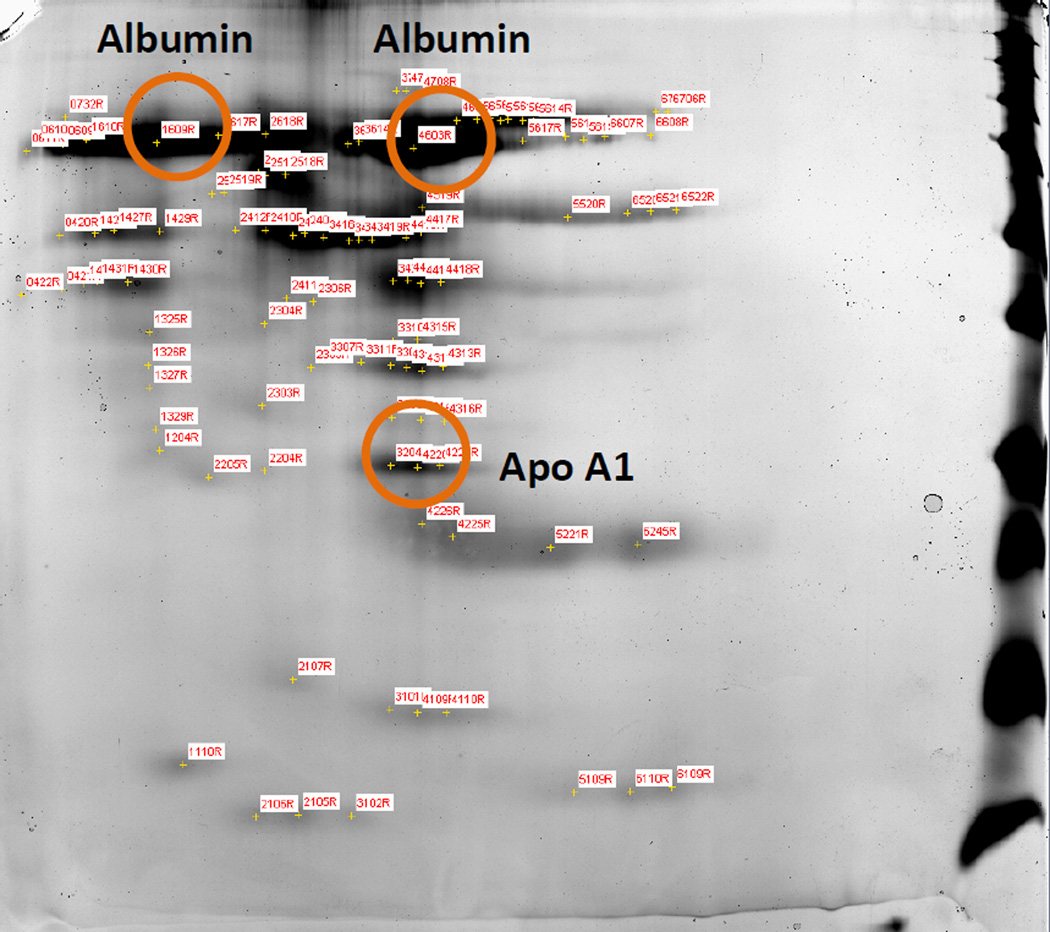

After intravenous administration, nanoparticles come in contact with a complex mixture of plasma proteins. As nanoparticles have a large surface area, they exhibit significant surface interaction with plasma proteins via hydrophobic or electrostatic interaction. These adsorbed proteins can govern the in vivo fate of the particles. Depending on the surface characteristics of the nanoparticles, different proteins will adsorb onto the surface. To identify the major adsorbed proteins on the Cellax nanoparticles, we incubated Cellax with plasma at 37°C for 1 h. The particles were then isolated, and the adsorbed proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis followed by analysis with mass spectrometry. Two proteins were identified exhibiting measurable binding with the Cellax particles, albumin (major) and apolipoprotein-A1 (Apo-A1, minor) (Figure 1). The other protein spots were all below the detection limit, suggesting minimal binding.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of plasma protein binding to Cellax. Two proteins were successfully identified: albumin (major) and Apo-A1 (minor).

Relative contribution of albumin and Apo-A1 in the cellular internalization of Cellax

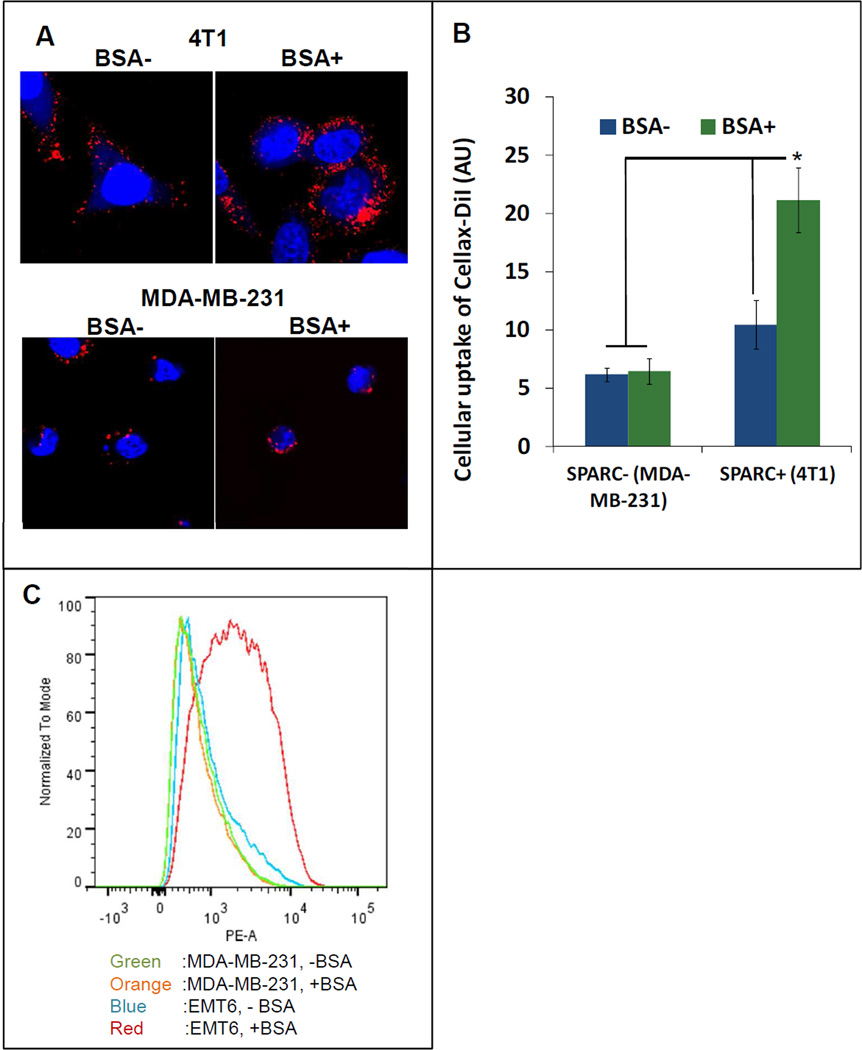

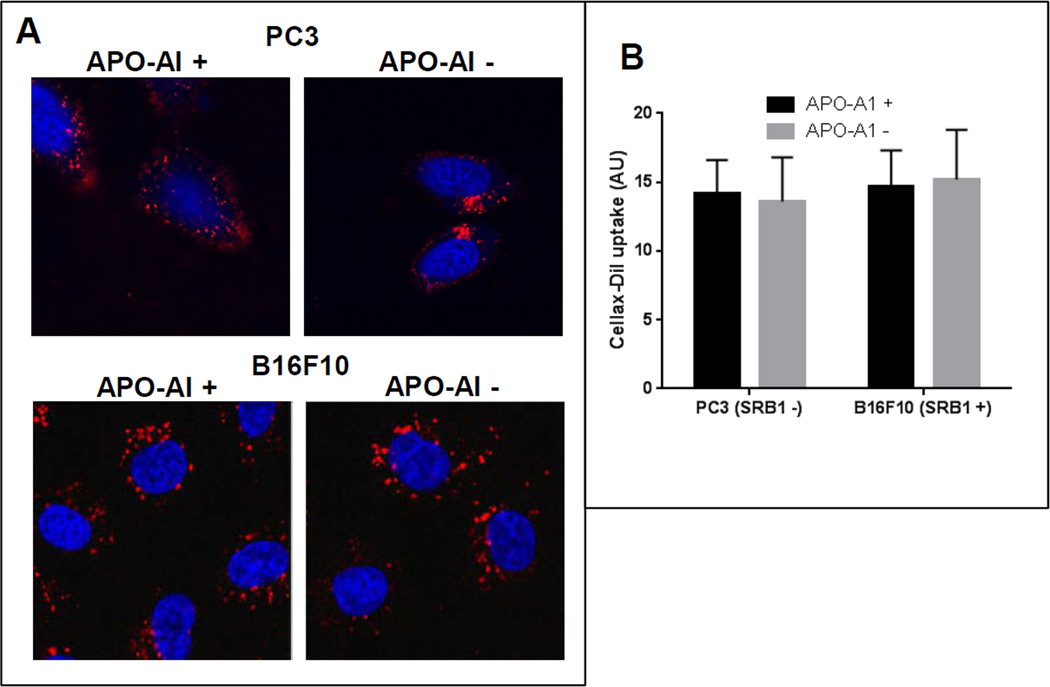

Both albumin and Apo-A1 have been shown to participate in the cellular internalization process of different nanoparticles [15, 16]. After adsorption onto the surface of the nanoparticles, they facilitate the nanoparticle uptake by binding with their respective cellular receptors. The major transmembrane receptor for albumin and Apo-A1 is secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) and scavenger receptor B1 (SRB1), respectively [17, 18]. These receptors are over-expressed in various tumor cells and their overexpression may enhance cellular uptake of these protein bound nanoparticles. To elucidate the role of albumin and Apo-A1 in the intracellular uptake of Cellax, we selected a pair of cell lines, SPARC-positive (4T1, EMT6) and SPARC-negative (MDA-MB-231) (Figure 2A–C, Supplementary Figure 1A) as well as SRB1-positive (B16F10) and SRB1-negative (PC3) (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 1B). In order to assess the significance of albumin and SPARC in cellular internalization of Cellax, SPARC-positive 4T1 and SPARC-negative MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with Cellax-DiI in the absence and presence of albumin (40 mg/mL BSA, the albumin concentration in serum). After 0.5 h, these cells were washed and cellular internalization of the Cellax particles were measured by confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 2, the presence of albumin significantly enhanced uptake of the Cellax particles in the SPARC-positive 4T1 cells by >2-fold. However, in the SPARC-negative MDA-MB-231 cells no difference was detected in the cellular internalization of Cellax in the presence or absence of albumin. In the presence of albumin, Cellax internalization was 4-fold higher in the SPARC-positive 4T1 cells in comparison to SPARC-negative MDA-MB-231 cells. However, the presence or absence of Apo-A1 and its receptor, SRB1 did not significantly influence the intracellular uptake of Cellax. As shown in Figure 3, irrespective of Apo-A1 treatment or expression of SRB1, the internalization of Cellax particles were similar, indicating no significant involvement of the Apo-A1/SRB1 pathway in cellular internalization of Cellax. These results suggest that the surface adsorbed albumin on the Cellax particles facilitated the cellular internalization into SPARC positive cells. As many tumor cells overexpress SPARC [19], and albumin is the major protein in serum, this pathway might be of importance in determining the in vivo efficacy of Cellax against tumor.

Figure 2.

Uptake of Cellax-DiI in SPARC+ and SPARC− cells in the absence and presence of BSA. (A) Confocal fluorescence microscopy images. Blue: nucleus; red: Cellax-DiI. (B) Image analysis of cell uptake in panel A was quantified using ImagePro. * indicates p<0.05. (C) Flow cytometry analysis.

Figure 3.

Uptake of Cellax-DiI in SRB1+ and SRB1− cells in the absence and presence of Apo-A1. (A) Confocal fluorescence microscopy images. Blue: nucleus; red: Cellax-DiI. (B) Image analysis of cell uptake in panel A was quantified using ImagePro.

Evaluation of Cellax-Albumin Binding Affinity

To understand the thermodynamics of Cellax-albumin binding, we employed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to characterize the binding. Serum albumin was titrated against Cellax nanoparticles or DTX to elucidate the thermodynamic characterization of the macromolecule ligand interaction including enthalpy, stoichiometry and affinity. The enthalpy (ΔH) of the association process, binding stoichiometry (n), binding constant (K), and binding entropy change (ΔS) were derived by fitting the plot of the heat change [kcal/mol injectant (serum albumin)] versus molar ratio of albumin per Cellax particle (Supplementary Figure 1) to a simple 1:1 isotherm binding model. Supplementary Figure 2 illustrates a typical titration curve generated from the raw data of the titration of albumin to Cellax and the resulting integrals. From this figure, the negative peaks indicate exothermic reactions corresponding to a negative enthalpy change. The data was fit with the assumption of a single binding site model; implications that the phenomenon of co-operativity, polisterism, and poliphasic processes are insignificant. From Table 1, it can be seen that the affinity was 2-fold higher for the native taxane (DTX) in comparison to Cellax. However, the binding affinity remained relatively strong for both DTX and Cellax as indicated by the micromolar scale. In addition, the number of binding sites for DTX was significantly less than Cellax (0.89 ± 0.03 compared to 8.21 ± 2.03). Therefore, the overall avidity of Cellax with albumin was 4-fold higher than that of DTX. The enthalpy change (ΔH) relates to the energy content of the bonds as they are broken or created during the binding event. The dominant contributor is through hydrogen bonding. The negative values for DTX and Cellax indicates an enthalpy change favoring the binding event through hydrogen bonding. Negative entropy change (ΔS) is an indication of changes in hydrophobic interactions and conformational changes during the binding event. Taken together, these parameters indicate a favorable binding event to both DTX and Cellax via hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, and the overall binding avidity between Cellax and albumin was 4-fold greater than that for the native taxane.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for the binding of Cellax and DTX to human serum albumin

| n | K (10−4 M−1) | ΔH (kcal mol−1) | ΔS (cal mol−1 K−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docetaxel | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 9.12 ± 1.43 | −9.51 | −11.95 |

| Cellax | 8.21 ± 2.03 | 4.72 ± 0.65 | −6.53 | −4.59 |

n = stoichiometry, K = binding constant, ΔH = binding enthalpy, ΔS = entropy change

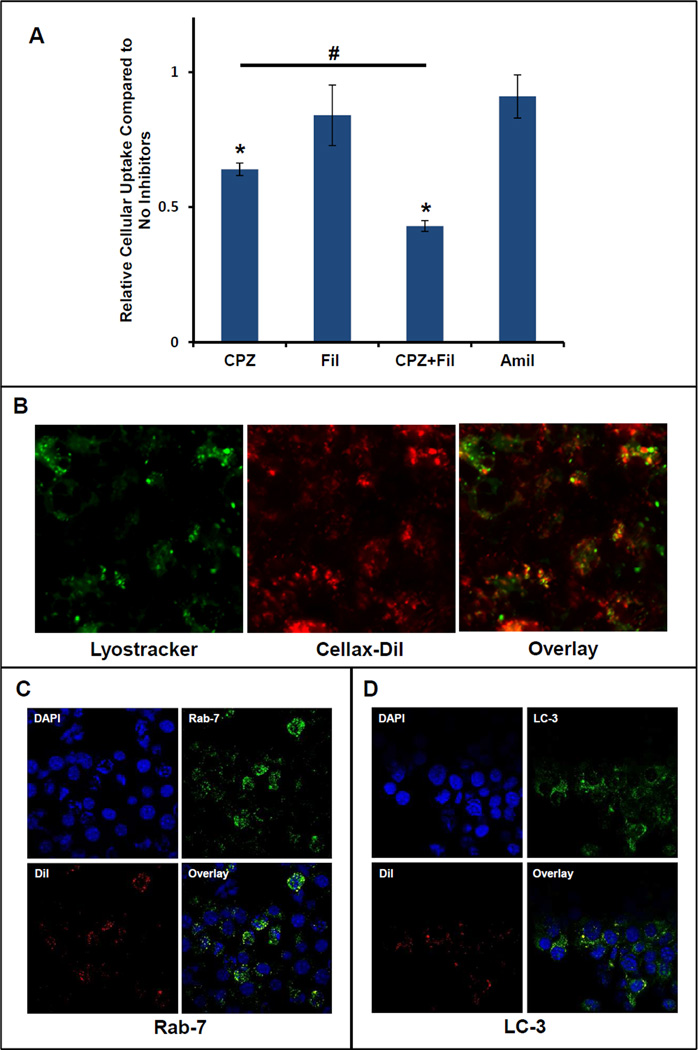

Internalization Pathway of Cellax Nanoparticles

After demonstrating that serum albumin efficiently adsorbed onto Cellax and the surface bound albumin facilitated cellular uptake via a SPARC dependent mechanism, we further studied the internalization pathway. We first determined whether Cellax internalization was an energy-dependent mechanism, and compared the cellular uptake of Cellax-DiI at 37°C and 4°C in EMT6 and U937 cells. As illustrated in Supplementary Figure 3, the cellular uptake of Cellax-DiI was abolished at 4°C, while that at 37°C was significant, suggesting the uptake of Cellax was mediated primarily by an energy-dependent internalization mechanism. Then we studied different internalization pathways using various endocytotic inhibitors including chlorpromazine (CPZ, inhibiting clathrin-mediated endocytosis), filipin III (Fil, inhibiting caveolae-mediated endocytosis) and amiloride (Amil, inhibiting micropinocytosis) that specifically interfere with one or multiple cellular endocytotic pathways. As shown in Figure 4A, chlorpromazine exhibited the highest inhibitory effect. Administration of chlorpromazine decreased the cellular internalization of Cellax to 67 ± 6% relative to control (cells that were not treated with inhibitors). Administration of amiloride or filipin III resulted in a slight decrease in Cellax uptake but not statistically significant. Interestingly, EMT6 cells treated with both chlorpromazine and amiloride concurrently followed by Cellax-DiI had an additive effect, resulting in a significant decrease in Cellax uptake relative to chlorpromazine alone (43 ± 2% and 67 ± 6%, respectively). Taken together, the inhibition studies demonstrated that uptake of Cellax nanoparticles was predominantly via a clathrin-mediated mechanism, with a minor involvement of the pinocytosis pathway.

Figure 4.

Cellular internalization of Cellax-DiI nanoparticles. (A) Internalization of Cellax-DiI after administration of different endocytotic inhibitors. EMT6 cells were treated with chlorpromazine to inhibit clathrin-mediated endocytosis, amiloride to inhibit micropinocytosis, or filipin III to inhibit caveolae formation. The fluorescent intensity is expressed as a ratio relative to cells treated with only Cellax-DiI. * indicates p<0.05 compared to the control. # indicates p<0.05 between the groups. (B) Co-localization of Cellax-DiI particles (red) with LysoTracker (green) in EMT6 cells (mag. = 200×). (C) Co-localization of Cellax-DiI particles (red) with late endosome marker Rab-7 (green) in EMT6 cells. (D) Co-localization of Cellax-DiI particles (red) with autophagosome marker LC3 (green) in EMT6 cells.

Intracellular Fate of Cellax Nanoparticles

As demonstrated in Figure 4B, Cellax-DiI (red) was co-localized with lysosomes (green) indicating that after internalization, Cellax nanoparticles were trafficked to lysosomes. Polymeric nanoparticles are normally internalized into the cells through endocytosis, which were then transported into lysosome [20]. To elucidate whether the internalization mechanism of Cellax was through endocytic pathway, we labelled the Cellax-DiI treated EMT6 cells with Rab-7, a late endosome marker. As depicted in Figure 4C, significant co-localization of Cellex-DiI and Rab-7 was found, indicating the involvement of endocytosis in the cellular internalization of Cellax.

Recently it has been demonstrated that polymeric nanoparticles containing taxanes induced autophagy after internalization into the tumor cells and a significant fraction of the particles were associated with autophagosomes [21, 22]. To further analyze whether the autophagosomal pathway also played a role in the intracellular fate of Cellax nanoparticles, co- localization study of Cellax-DiI and autophagosome was performed. We found a considerable level of co-localization of Cellax-DiI and LC3, an autophagosome marker [23] (Figure 4D), signifying autophagy induction and uptake of Cellax nanoparticles by autophagosome.

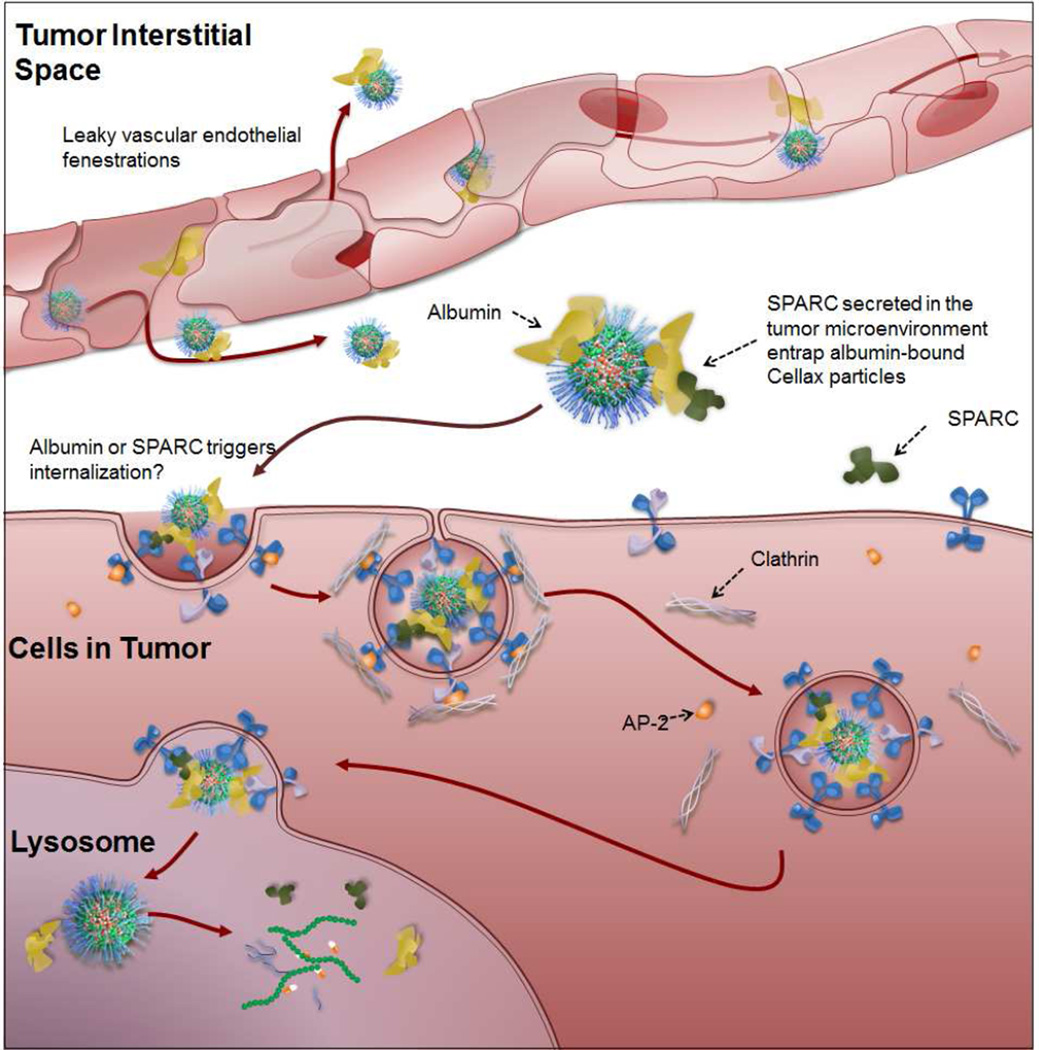

Thus far, our data suggest that Cellax bound with serum albumin efficiently, and its cellular internalization was facilitated in the presence of SPARC, an albumin receptor, predominantly via a clathrin-mediated mechanism, involving the endo-lysosomal and autophagosomal pathways. We further analyzed whether the level of SPARC in tumors was correlated to the efficacy of Cellax in animal models.

Antitumor efficacy of Cellax is correlated with SPARC expression of the tumor

We first selected a panel of tumor cell lines expressing different levels of SPARC. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1A, while B16F10, EMT6 and LL/2 expressed a moderate to high level of SPARC, the SPRAC expression in MDA-MB-231 and PC3 was negligible. We then compared the antitumor efficacy of native DTX and Cellax against tumors established with these cell lines (Figure 5A–E), and the correlation between SPARC expression and tumor growth inhibition after treatment with Cellax or DTX was evaluated (Figure 5F,G). As shown in Figure 5F, there was a positive linear correlation between the tumor SPARC level and the Cellax efficacy (R2=0.9). However, no correlation was found for the tumor SPARC level and the activity of native DTX (Figure 5G). The difference in Cellax efficacy against these different tumors could not be explained by the intrinsic difference in cytotoxic potency of Cellax, as the in vitro IC50s of Cellax against this panel of tumor lines were similar and between 3 and 10 nM. Instead, the data suggest that the difference in Cellax efficacy was attributed to the different bioavailability of Cellax to these tumors; Cellax displayed enhanced activity to tumors with an increased level of SPARC. This in vivo result supports the data obtained with the in vitro mechanistic study: SPARC was required for Cellax delivery.

Figure 5.

Antitumor efficacy of native DTX and Cellax in a panel of tumor models (A–E) and the correlation between efficacy and tumor SPARC levels (F: Cellax and SPARC; G: DTX and SPARC).

Cellax is a promising new drug for cancer therapy, demonstrating significant improvements in safety and efficacy in multiple tumor models compared to the native drug, DTX [2–8]. In previous in vivo evaluations of Cellax, significant cellular internalization was observed in multiple tumor models [2, 4, 5], prompting further investigation into the molecular mechanism of how these PEGylated and non-charged nanoparticles interact with tumor cells. An improved understanding of the mechanism might also help identify a biomarker to better stratify tumors which respond to Cellax therapy, and this could lead to improved success rates in future clinical trials for Cellax.

Since Cellax is a PEGylated formulation with a near neutral zeta potential and the CMC backbone is known to be inert, it was hypothesized that Cellax itself is not recognized by any cell surface receptors. However, in cell culture tests, efficient cellular internalization of Cellax nanoparticles was repeatedly observed in serum containing media. One possibility is that Cellax binds with serum proteins, which are then recognized by cells for endocytosis. There are two aspects of Cellax nanoparticles supporting this hypothesis: (a) Cellax is not heavily PEGylated (5 wt%), leaving sufficient room for serum protein binding; and (b) The Cellax backbone (CMC-ac) is hydrophobic, increasing the possibility of binding to proteins such as albumin. DiI is passively encapsulated within Cellax and does not alter the surface properties of Cellax, so it is not expected to change the interaction with serum proteins or cells. Analysis of the 1-D gel electrophoresis by mass spectrometry revealed that Cellax bound predominantly to albumin and to a lesser extent Apo-A1. This is not unexpected as albumin is the most abundant protein in serum (~50 mg/mL). We established through uptake studies that albumin and its receptor SPARC played a critical role in the cellular internalization of Cellax. SPARC has been identified as a molecular binder for albumin to facilitate drug targeting [17, 24, 25]. SPARC or osteonectin is a glycosylated 43 kDa protein with high affinity to albumin. It is highly up-regulated in a variety of cancers including breast, lung, liver, kidney, prostate, head and neck, melanoma, brain, and thyroid [19, 26–28]. Although both cancer epithelial and reactive stromal cells can produce SPARC, owing to the acidity and hypoxic nature of the tumor microenvironment, it is often highly overexpressed within the tumor-stromal interface [28, 29]. Overexpression of SPARC is often associated with poor disease prognosis due to tumor progression and metastasis [25, 30, 31]. For example, SPARC overexpression has been shown to be a prognostic indicator of poor overall survival in head and neck cancer patients [25, 32, 33].

There are four major internalization pathways [34–36]: (a) clathrin-mediated endocytosis is mediated by small (~100 nm) vesicles that are characterized by a crystalline coat made up mainly of the cytosolic protein clathrin. Many proteins and growth factors enter cells via this mechanism, including low density lipoprotein, transferrin, integrin and epidermal growth factor. The vesicles later fuse with endosomes/lysosomes. (b): the caveolae pathway, which internalizes substances via small (~50 nm) flask-shape pits enriched with caveolin, cholesterol and glycolipids. This pathway does not involve endosomes/lysosomes. (c): macropinocytosis is the invagination of the cell membrane to form a pocket that pinches off into the cell to form a vesicle (0.5–5 µm in diameter) filled with extracellular fluid. This occurs in a non-specific manner and the vesicle travels into cytosol and fuses with an endosome/lysosome. (d): phagocytosis is the mechanism for cells to internalize particulate matters larger than 0.75 µm in diameter, which only occurs in specialized cells, such as macrophages. The vesicle also fuses with endosomes/lysosomes. Our data suggest Cellax uptake was primarily via clathrin-mediated endocytosis with a minor level via non-specific micropinocytosis.

Upon internalization, the Cellax nanoparticles were efficiently entrapped within the endo-lysosomal compartment wherein the acidic environment of the lysosomes would break down the nanoparticles and release the drug (Figure 6). Confocal fluorescence microscopy reveals strong co-localization between internalized Cellax nanoparticles and endosomes/lysosomes. Moreover, further analysis of the intracellular fate of Cellax nanoparticles suggests that Cellax induced autophagy, leading to production of autophagosome in the cells that in turn took up a significant fraction of the internalized Cellax nanoparticles. Similar results with other taxane containing polymeric micelles have been reported [21, 22].

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanism of delivery for Cellax nanoparticles. Cellax adsorbs albumin in circulation and is deposited within the tumor interstitium via exploitation of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. SPARC produced in the tumor microenvironment binds to the surface albumin on the Cellax nanoparticles and thus traps the particles in the tumor. Cellax is internalized via a clathrin-mediated mechanism and finally ends up in the endolysosomal compartment, where the polymer is broken down and the drug is released.

Analysis of the mRNA expression of SPARC and tumor growth inhibition via Cellax therapy revealed a positive, linear correlation. Such correlation was not observed with native DTX. This albumin and SPARC dependent pathway for Cellax delivery should be further validated in a clinical setting to identify a biomarker and develop a reproducible stratifying method to efficiently select patients that will respond to Cellax therapy. Contrary to the prior reports, we did not measure any significant correlation between the tumor SPARC level and the efficacy of Nab-paclitaxel in our animal models (Supplementary Figure 4) [25]. It is postulated that after i.v. administration, paclitaxel rapidly dissociated from the albumin nanoparticles, and therefore could not leverage the SPARC-targeted delivery. This hypothesis is supported by two pieces of evidence: (a) the avidity between taxane and albumin was 4-fold lower than that of Cellax and albumin; (b) the pharmacokinetic profiles of native paclitaxel and Nab-paclitaxel were comparable, showing rapid blood clearance (t1/2 = 6.2 ± 1.2 h) [4], while albumin is a long circulating molecule (t1/2 = 15–19 d) [37].

Recently, our team discovered that Cellax targeted cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in the tumor microenvironment [5]. More than 85% of the Cellax nanoparticles in the tumor were associated with CAFs, resulting in significant tumor stromal depletion, tumor microenvironment modulation and reduction of metastasis. We (Murakami et al. unpublished data) and others [30, 38, 39] have shown that CAFs expressed a high level of SPARC, and the demonstration that Cellax was internalized by cells via a SPARC dependent mechanism might explain Cellax’s CAFs-targeting activity.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated that Cellax adsorbed albumin efficiently with a 4-fold increased avidity compared to native DTX, and was internalized by cells via an albumin and SPARC dependent mechanism. The particles were taken up primarily through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and ended up in autophagosomes-lysosomes of cells in the tumor microenvironment expressing SPARC. This drug delivery mechanism of Cellax is further supported by the in vivo efficacy data showing a positive correlation between the tumor SPARC level and the antitumor efficacy of Cellax.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. mRNA level of SPARC (A) SRB1 (B) in different tumor cell lines

Supplementary Figure 2. ITC chromatograph of albumin binding kinetics to Cellax.

Supplementary Figure 3. Confocal fluorescence microscopy of Cellax-DiI uptake by EMT6 and U937 cells at 4°C and 37°C.

Supplementary Figure 4. Correlation between the antitumor efficacy of Nab-paclitaxel and the expression of SPARC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by grants from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research Intellectual Property Development and Commercialization Fund, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PPP-122898) and National Institutes of Health (CA17633901). S.D. Li is a recipient of a Coalition to Cure Prostate Cancer Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation and a New Investigator Award from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MSH-130195). Funding for the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research is provided by the Government of Ontario. The authors would like to thank the Winnik Research Group for their assistance with the isothermal titration calorimetry experiments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sengupta S, Kulkarni A. Design principles for clinical efficacy of cancer nanomedicine: a look into the basics. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2878–2882. doi: 10.1021/nn4015399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernsting MJ, Tang WL, MacCallum N, Li SD. Synthetic modification of carboxymethylcellulose and use thereof to prepare a nanoparticle forming conjugate of docetaxel for enhanced cytotoxicity against cancer cells. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:2474–2486. doi: 10.1021/bc200284b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ernsting MJ, Foltz WD, Undzys E, Tagami T, Li SD. Tumor-targeted drug delivery using MR-contrasted docetaxel - carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3931–3941. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernsting MJ, Murakami M, Undzys E, Aman A, Press B, Li SD. A docetaxel-carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticle outperforms the approved taxane nanoformulation, Abraxane, in mouse tumor models with significant control of metastases. J Control Release. 2012;162:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murakami M, Ernsting MJ, Undzys E, Holwell N, Foltz WD, Li SD. Docetaxel conjugate nanoparticles that target alpha-smooth muscle actin-expressing stromal cells suppress breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4862–4871. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy A, Murakami M, Ernsting MJ, Hoang B, Undzys E, Li SD. Carboxymethylcellulose-based and docetaxel-loaded nanoparticles circumvent P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:2592–2599. doi: 10.1021/mp400643p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoang B, Ernsting MJ, Murakami M, Undzys E, Li SD. Docetaxel-carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticles display enhanced anti-tumor activity in murine models of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int J Pharm. 2014;471:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernsting MJ, Tang WL, MacCallum NW, Li SD. Preclinical pharmacokinetic, biodistribution, and anti-cancer efficacy studies of a docetaxel-carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticle in mouse models. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1445–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aggarwal P, Hall JB, McLeland CB, Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Nanoparticle interaction with plasma proteins as it relates to particle biodistribution, biocompatibility and therapeutic efficacy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao H, He Q. The interaction of nanoparticles with plasma proteins and the consequent influence on nanoparticles behavior. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11:409–420. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.877442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iversen T-G, Skotland T, Sandvig K. Endocytosis and intracellular transport of nanoparticles: Present knowledge and need for future studies. Nano Today. 2011;6:176–185. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alhaddad A, Durieu C, Dantelle G, Le Cam E, Malvy C, Treussart F, et al. Influence of the internalization pathway on the efficacy of siRNA delivery by cationic fluorescent nanodiamonds in the Ewing sarcoma cell model. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahmoudi M, Lynch I, Ejtehadi MR, Monopoli MP, Bombelli FB, Laurent S. Protein-nanoparticle interactions: opportunities and challenges. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5610–5637. doi: 10.1021/cr100440g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood MA, Walker WH. USF1/2 transcription factor DNA-binding activity is induced during rat Sertoli cell differentiation. Biology of reproduction. 2009;80:24–33. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.070037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kratzer I, Wernig K, Panzenboeck U, Bernhart E, Reicher H, Wronski R, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I coating of protamine-oligonucleotide nanoparticles increases particle uptake and transcytosis in an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. J Control Release. 2007;117:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low K, Wacker M, Wagner S, Langer K, von Briesen H. Targeted human serum albumin nanoparticles for specific uptake in EGFR-Expressing colon carcinoma cells. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnitzer JE, Oh P. Antibodies to SPARC inhibit albumin binding to SPARC, gp60, and microvascular endothelium. The American journal of physiology. 1992;263:H1872–H1879. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Beer MC, Durbin DM, Cai L, Jonas A, de Beer FC, van der Westhuyzen DR. Apolipoprotein A-I conformation markedly influences HDL interaction with scavenger receptor BI. Journal of lipid research. 2001;42:309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Said N, Theodorescu D. Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (Sparc) in Cancer. Journal of Carcinogenesis & Mutagenesis. 2013;4:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bae YM, Park YI, Nam SH, Kim JH, Lee K, Kim HM, et al. Endocytosis, intracellular transport, and exocytosis of lanthanide-doped upconverting nanoparticles in single living cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33:9080–9086. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Dong Y, Zeng X, Liang X, Li X, Tao W, et al. The effect of autophagy inhibitors on drug delivery using biodegradable polymer nanoparticles in cancer treatment. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1932–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Zeng X, Liang X, Yang Y, Li X, Chen H, et al. The chemotherapeutic potential of PEG-b-PLGA copolymer micelles that combine chloroquine as autophagy inhibitor and docetaxel as an anti-cancer drug. Biomaterials. 2014;35:9144–9454. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and Autophagy. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;445:77–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-157-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miele E, Spinelli GP, Miele E, Tomao F, Tomao S. Albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel (Abraxane ABI-007) in the treatment of breast cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2009;4:99–105. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desai N, Trieu V, Damascelli B, Soon-Shiong P. SPARC Expression Correlates with Tumor Response to Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Translational oncology. 2009;2:59–64. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prenzel KL, Warnecke-Eberz U, Xi H, Brabender J, Baldus SE, Bollschweiler E, et al. Significant overexpression of SPARC/osteonectin mRNA in pancreatic cancer compared to cancer of the papilla of Vater. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:1397–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas R, True LD, Bassuk JA, Lange PH, Vessella RL. Differential expression of osteonectin/SPARC during human prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1140–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neuzillet C, Tijeras-Raballand A, Cros J, Faivre S, Hammel P, Raymond E. Stromal expression of SPARC in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2013;32:585–602. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Brekken RA, Sivridis E, Gatter KC, Harris AL, et al. Enhanced expression of SPARC/osteonectin in the tumor-associated stroma of non-small cell lung cancer is correlated with markers of hypoxia/acidity and with poor prognosis of patients. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5376–5380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podhajcer OL, Benedetti L, Girotti MR, Prada F, Salvatierra E, Llera AS. The role of the matricellular protein SPARC in the dynamic interaction between the tumor and the host. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2008;27:523–537. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Framson PE, Sage EH. SPARC and tumor growth: where the seed meets the soil? J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:679–690. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato Y, Nagashima Y, Baba Y, Kawano T, Furukawa M, Kubota A, et al. Expression of SPARC in tongue carcinoma of stage II is associated with poor prognosis: an immunohistochemical study of 86 cases. International journal of molecular medicine. 2005;16:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chin D, Boyle GM, Williams RM, Ferguson K, Pandeya N, Pedley J, et al. Novel markers for poor prognosis in head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:789–797. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song Q, Wang X, Hu Q, Huang M, Yao L, Qi H, et al. Cellular internalization pathway and transcellular transport of pegylated polyester nanoparticles in Caco-2 cells. Int J Pharm. 2013;445:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harush-Frenkel O, Debotton N, Benita S, Altschuler Y. Targeting of nanoparticles to the clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007;353:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nam HY, Kwon SM, Chung H, Lee SY, Kwon SH, Jeon H, et al. Cellular uptake mechanism and intracellular fate of hydrophobically modified glycol chitosan nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2009;135:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie D, Yao C, Wang L, Min W, Xu J, Xiao J, et al. An albumin-conjugated peptide exhibits potent anti-HIV activity and long in vivo half-life. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2010;54:191–196. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00976-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang RF, Moore T, Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Amos KD, Rivera A, et al. Cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:918–926. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez MV, Viale DL, Cafferata EG, Bravo AI, Carbone C, Gould D, et al. Tumor associated stromal cells play a critical role on the outcome of the oncolytic efficacy of conditionally replicative adenoviruses. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. mRNA level of SPARC (A) SRB1 (B) in different tumor cell lines

Supplementary Figure 2. ITC chromatograph of albumin binding kinetics to Cellax.

Supplementary Figure 3. Confocal fluorescence microscopy of Cellax-DiI uptake by EMT6 and U937 cells at 4°C and 37°C.

Supplementary Figure 4. Correlation between the antitumor efficacy of Nab-paclitaxel and the expression of SPARC.