Abstract

Melioidosis has protean manifestations and often mimics other disease processes. We present a case of a gentleman presenting with chronic cough whose initial radiographic findings of a cavitatory lung lesion and mediastinal lymphadenopathy were suggestive of tuberculosis. This case highlights the important role that bronchoscopy and endobronchial ultrasound can play in the diagnosis of melioidosis in patients presenting with mediastinal lymphadenopathy whose initial microbiological findings from sputum are negative for tuberculosis.

Keywords: Melioidosis, tuberculosis, bronchoscopy, endobronchial ultrasound, mediastinal lymphadenopathy

Background

A 52 year-old Chinese man with no past medical history was referred to the respiratory clinic with a one-month history of a non-productive cough. He worked as a labourer on construction sites and had a 30 pack years history of smoking. Otherwise the history and physical examination were unrevealing.

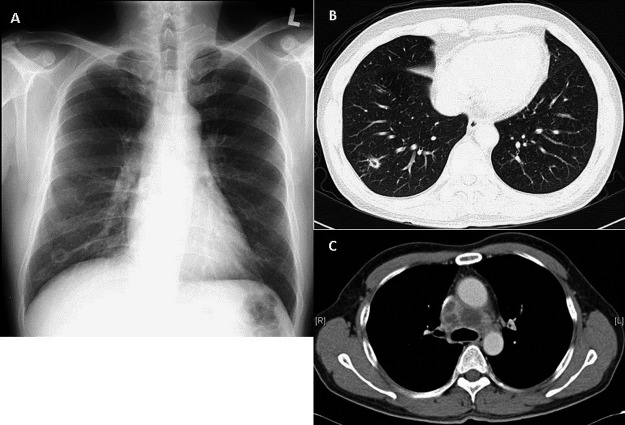

Chest roentgenogram demonstrated a cavitatory lesion in the right lower zone with computed tomography scan of the thorax revealing the cavitatory lesion in the lateral-basal segment of the right lung, multiple enlarged mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Figure 1A, 1B, 1C) and tree-in-bud nodules in the upper lobes. The findings were suggestive of pulmonary tuberculosis with endobronchial spread of the disease, although the initial microbiological results from induced sputum for acid fast bacilli (AFB) and respiratory pathogens were negative.

Fig. 1.

A: A 1.9 × 1.6 cm cavitatory lesion seen in the right lower zone.

B: A 1.2 × 1.0 cm cavitatory lesion seen in the lateral-basal segment of the right lung with an adjacent area of traction bronchiectasis.

C: 4 enlarged pre-tracheal lymph nodes with hypoattenuate centres, in keeping with necrosis of the lymph nodes. The largest measures 2.6 × 2.1 cm.

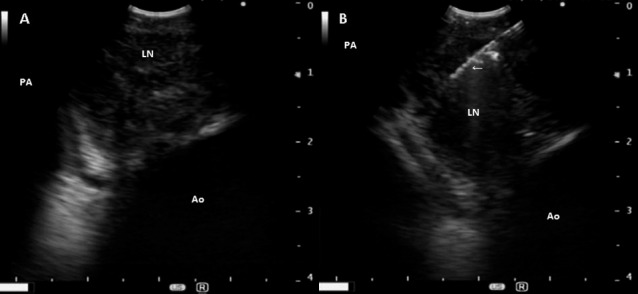

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) and fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the precarinal lymph node were performed (Figure 2A, 2B) following bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). BAL cultures returned negative for both respiratory pathogens and AFB. Histology of the FNA sample demonstrated necrotising granulomas with no AFB seen. Alarmingly, the culture of the lymph node aspirate came back positive for Burkholderia pseudomallei.

Fig. 2.

A: Endobronchial ultrasound showing enlarged precarinal lymph node (LN).

B: Fine needle aspiration (arrow) of precarinal lymph node (LN) guided by endobronchial ultrasound. PA—pulmonary artery; Ao—aorta.

The patient was started on intravenous ceftazidime, receiving it on an outpatient basis for four weeks. Thereafter, he was given a 6-month course of oral doxycycline and co-trimoxazole. He remained well and reported marked improvement regarding his cough. Repeat chest roentgenogram also demonstrated resolution of the right lower zone cavitatory lesion.

Melioidosis

Melioidosis is a fatal disease caused by the Gram-negative bacillus Burkholderia pseudomallei [1]. It is endemic in areas such as Northern Territory, Australia and Southeast Asian countries like Thailand, Singapore and Vietnam [2, 3]. Its presentations can be capricious, ranging from pneumonia to arthritis. Its severity can vary from a fulminant septic process to that of a chronic infective process which may mimic malignancy or tuberculosis in some cases [4, 5].

Given its protean presentations, melioidosis needs to be ruled out in areas where both tuberculosis and melioidosis are endemic even if initial radiological findings are suggestive of tuberculosis. In these areas, bronchoscopy and EBUS-FNA can be invaluable tools in helping with the diagnosis of melioidosis in patients presenting with mediastinal lymphadenopathy and whose initial investigations are negative for tuberculosis.

Acknowledgement

We do not have any actual or potential conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.White NJ. Melioidosis. Lancet 2003; 361: 1715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Currie BJ, Ward L, Cheng AC. The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4: e900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Limmathurotsakul D, Wongratanacheewin S, Teerawattanasook N, et al. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in Northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 82: 1113–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currie BJ. Melioidosis: an important cause of pneumonia in residents of and travellers returned from endemic regions. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiersinga WJ, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1035–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]