Membrane targeting of the β2e subunit is dynamically regulated by M1 muscarinic receptor signaling to promote fast inactivation of CaV2.2.

Abstract

High voltage-activated Ca2+ (CaV) channels are protein complexes containing pore-forming α1 and auxiliary β and α2δ subunits. The subcellular localization and membrane interactions of the β subunits play a crucial role in regulating CaV channel inactivation and its lipid sensitivity. Here, we investigated the effects of membrane phosphoinositide (PI) turnover on CaV2.2 channel function. The β2 isoform β2e associates with the membrane through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. Using chimeric β subunits and liposome-binding assays, we determined that interaction between the N-terminal 23 amino acids of β2e and anionic phospholipids was sufficient for β2e membrane targeting. Binding of the β2e subunit N terminus to liposomes was significantly increased by inclusion of 1% phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) in the liposomes, suggesting that, in addition to phosphatidylserine, PIs are responsible for β2e targeting to the plasma membrane. Membrane binding of the β2e subunit slowed CaV2.2 current inactivation. When membrane phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate and PIP2 were depleted by rapamycin-induced translocation of pseudojanin to the membrane, however, channel opening was decreased and fast inactivation of CaV2.2(β2e) currents was enhanced. Activation of the M1 muscarinic receptor elicited transient and reversible translocation of β2e subunits from membrane to cytosol, but not that of β2a or β3, resulting in fast inactivation of CaV2.2 channels with β2e. These results suggest that membrane targeting of the β2e subunit, which is mediated by nonspecific electrostatic insertion, is dynamically regulated by receptor stimulation, and that the reversible association of β2e with membrane PIs results in functional changes in CaV channel gating. The phospholipid–protein interaction observed here provides structural insight into mechanisms of membrane–protein association and the role of phospholipids in ion channel regulation.

INTRODUCTION

This paper concerns the localization and actions of a regulatory subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ (CaV) channels. The intracellular Ca2+ ion is a potent second messenger, important for diverse biological processes such as neurotransmitter release, hormone secretion, excitation–contraction coupling, and gene expression. CaV channels, which are multi-protein complexes made up of at least three types of subunit named α, β, and α2δ, are major machinery for Ca2+ influx (Catterall, 2000; Ertel et al., 2000). Thus, regulation of CaV channels is critical for maintaining a variety of cellular signaling. The β subunits are intracellular proteins directly associated with the large pore-forming α1 subunits. They tune the electrophysiological and kinetic properties of the channel (Buraei and Yang, 2010; Waithe et al., 2011). Equally importantly, they act as chaperones to traffic α1 subunits to the plasma membrane and confer functional complexity on CaV channels (Bichet et al., 2000; Altier et al., 2011). Unlike the other cytosolic β subunits, the β2a subunit is known to be posttranslationally palmitoylated at two cysteines of the N terminus and therefore is localized on the plasma membrane. It slows the inactivation of CaV channels (Chien et al., 1996; Qin et al., 1998; Hurley et al., 2000). With other cytosolic (nonlipidated) subunits, CaV channels can be inhibited by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) depletion, but with the lipidated β2a subunit, channels are much less sensitive to PIP2 depletion (Heneghan et al., 2009; Roberts-Crowley et al., 2009; Suh et al., 2012). Similar to the β2a subunit, the β2e subunit is localized at the plasma membrane even in the absence of α1 subunit, and it slows the inactivation of CaV channels (Takahashi et al., 2003; Link et al., 2009). Recently, Miranda-Laferte et al. (2014) have reported that with protein–liposome cosedimentation assays, this membrane targeting of the β2e subunit depends on the interaction of its N terminus, which consists of positively charged residues, with plasma membrane phosphatidylserine (PS) (Miranda-Laferte et al., 2014). Thus, the membrane localization of β subunits by lipidation contributes unique properties to CaV channels. However, the functional roles of β subunits in the modulation of CaV channels by Gq protein–coupled receptors (GqPCRs) remain to be further explained.

The subcellular distribution of peripheral membrane proteins is regulated in part by unique interactions between the protein and the cytoplasmic lipid leaflet of the membrane (Cho and Stahelin, 2005; Rosenhouse-Dantsker and Logothetis, 2007; van Meer et al., 2008). Indeed, for the plasma membrane, the lipid composition plays an important role in many cellular processes involving signal transduction, protein trafficking, cytoskeleton organization, and vesicular transport (McLaughlin and Murray, 2005; Balla, 2013). In particular, anionic plasma membrane lipids including phosphatidic acid, PS, and phosphoinositides (PIs) not only recruit peripheral proteins to the plasma membrane but also allow them to be involved in a wide variety of signaling pathways in a spatio-temporally organized manner. Especially, the levels of phospholipids are intensely regulated by receptor signal transductions and intracellular energy metabolism. Thus, the dynamics in the interaction of peripheral proteins to the plasma membrane would be very important for the functional regulation of membrane molecules (DiNitto et al., 2003).

Here, we investigated the effect of reversible interaction between the β2e subunit and the plasma membrane PI phospholipids on regulation of CaV channels. The β2e subunit is a splice variant of a single β2 gene and is expressed broadly in excitable tissues, such as brain, heart, lung, and kidney, in rodents and human (Massa et al., 1995; Colecraft et al., 2002; Link et al., 2009). Using a series of experimental approaches including in vitro binding assays between peptides and liposomes and rapamycin-inducible dimerization, we found that β2e subunits are membrane localized through interactions between the β2e N terminus and PI phospholipids, and that the depletion of membrane PIs accelerates the inactivation of CaV2.2 channels. In addition, Gq-coupled muscarinic receptor stimulation triggers translocation of the β2e subunit to the cytosol and enhances the current inactivation. Our results suggest that β2e regulates CaV channels through a reversible interaction with membrane poly-PIs, a different membrane-targeting mechanism from that of the β2a subunit. These findings provide better understanding of the role of PIs in direct interaction between plasma membrane and peripheral proteins as well as in ion channel regulation by membrane phospholipids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNAs

The following calcium channel subunits were used: rat β2a (M80545; provided by W.A. Catterall, University of Washington, Seattle, WA); rat β2a (C3,4S; provided by J. Hurley, Indiana University, Bloomington IN); α1B (GenBank accession no. AF055477), rat β3 (RefSeq accession no. NM_012828), and rat α2δ-1 (AF286488; provided by D. Lipscombe, Brown University, RI); Lyn-β3-YFP, RFP-Dead, RFP-Sac1, RFP-INPP5E, and RFP-PJ (provided by B. Hille, University of Washington); M1 muscarinic receptor (M1R; provided by N.N. Nathanson, University of Washington); and M2 muscarinic receptor (Guthrie Resource Center, Rolla, MO).

Mouse β2e cloning

Mouse brain cDNA library was isolated from 2-mo-old C57 male mice. This PCR product of brain cDNA library was amplified by PCR using the primers of β2b (GenBank accession no. AF423193) and β2e (RefSeq accession no. XM_006497319) subunits: β2b forward primer: 5′-CGCTAGCAGCATTCTGCACCCTGTTG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CGGATCCCCTTGGCGGATGTATACATCCCTG-3′; β2e forward primer: 5′-CGCTAGCATGAAGGCCACCTGGATCAGGCTT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CGGATCCCCTTGGCGGATGCGGATCCCCTTGGCGGATGTATACATCCCT-3′. The cDNAs encoding the mouse β2 subunits were TA cloned into T-easy vector (Promega) and cloned in pCDNA3.1, pEGFP-N1 (Takara Bio Inc.), and mCherry-N1 (Takara Bio Inc.). For the β2e/3 chimeric construct, the N-terminal region (69 base pairs) of β2e subunit was amplified by PCR using mouse β2e subunit and the following primers: forward primer: 5′-CCGGTACCATGAAGGCCACCTGGAGGCTT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CCGGTACCACAGATGTCCGAACTCTTCAGC-3′. For insertion of N terminus of β2e in β3, Kpn1 site was generated in the N-terminal region of β3 using point mutagenesis using the following primer: sense: 5′-GGTACCGTCGACTGCAGAATTCGAAGCTTG-3′, antisense: 5′-TAGGAGTCGGCGGTACCCGCCTCCGAGTC-3′. Constructs were subsequently inserted into the N-terminal region of β3 for expression. An N-terminal region–deleted construct of β2e subunit was amplified by PCR using the following primers: forward primer: 5′-GCCATGGTTGGTTTTCGGCAGACTCCTACACCAG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CGGATCCCCTTGGCGGATGTATACATCCC-3′.

RNA isolation

For analysis of mRNA expression profile, cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and hypothalamus were removed from 2-mo-old C57 male mice, following national and international standards of animal care and welfare. Total RNA from each brain tissue was extracted from homogenized samples using RNAgents total RNA isolation system (Promega). The total RNA of brain tissues was used to generate double-strand cDNA using SuperScript III reverse transcription (Invitrogen).

Quantitative SYBR Green real-time RT-PCR assay

The relative abundance of β2a and β2e subunits was determined using CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR machine (Bio-Rad Laboratories), using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The following primers were used for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) of fragments of β subunits and β actin using cDNA from various mouse brain tissues: β2a forward primer: 5′-ATGCAGTGCTGCGGGCTGGTACAT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CATGCCAGGCACCGGAACGTCAT-3′; β2a forward primer: 5′-TGAAGGCCACCTGGATCAGGCTTC-3′; and as a control, β-actin forward primer: 5′-TGTTTGAGACCTTCAACACC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TAGGAGCCAGAGCAGTAATC-3′. The qRT-PCR was set up in a 20-µl reaction volume containing 10 µl of 2× SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix, 1.5 µl cDNA (100 ng), 1 µl (10 µM) of each primer, and 5.5 µl of nuclease-free water. The optimized cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s, primer annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 20 s. A melt curve analysis was performed after amplification to verify the specificity of the amplified products. Melting curve analysis consisted of 65°C for 15 s, followed by temperature from 55 to 96°C in increments of 0.5°C with continuous reading of fluorescence. Each sample was quantified by determining the cycle threshold, and triplicate qRT-PCR reactions were done for β2a and β2e subunits. To evaluate concentrations of β2a, β2e, and β actin in brain tissues, Gene Expression Module of CFX manager software (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used.

Cell culture and transfection

TsA201 cells were maintained in DMEM (HyClone; Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.2% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. For transfection, cells were plated in 3.5-cm culture dishes at 50–80% confluency. For CaV channel expression, cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The transfected DNA mixture consisted of plasmids encoding α1, β, and α2δ-1 at a 1:1:1 molar ratio. When needed, enhanced GFP was also included in DNA mixtures. Cells were plated on poly-l-lysine–coated chips the day after transfection. Currents were recorded within 2 d after transfection.

Preparation of liposomes

All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., except N-[5-(dimethylamino) naphthalene-1-sulfonyl]-1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (dansyl-PE), from Invitrogen. Liposomes consist of PC (l-α-phosphatidylcholine), PE (l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine), PS (l-α-phosphatidylserine), cholesterol, dansyl-PE, and PIP2, and (44:10:15:25:5:1 mol percent). In case of no PS or PIP2, the PC content was adjusted accordingly. In brief, the lipid mixture was dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen in the hood, thereby generating a lipid film. The film was then dissolved with 100 µl of buffer containing 150 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES/KOH, pH 7.4, and 5% sodium cholate. A size-exclusion column was applied to remove detergent (Sephadex G50 in 150 mM KCl and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Liposomes were collected as eluted (∼400 µl); note that liposomes were easily detected by UV because of dansyl-PE.

Assay for peptide–liposome binding

Binding of peptide to liposomes was monitored using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements in which dansyl-PE incorporated in liposomes quenches the fluorescence of tryptophan in the peptide (Nalefski and Falke, 2002). All measurements were performed in a Fluoromax (HORIBA Scientific) and performed at 37°C in 1 ml of buffer containing 150 mM KCl and 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4. The peptide (750 nM) contains one tryptophan residue. Tryptophan was excited at 280 nm (slit width of 5 nm), and emission spectra were recorded from 320 to 420 nm (slit width of 5 nm) with the peak at 355 nm. FRET was normalized as F0/F, where F0 and F represent the fluorescence intensity at 355 nm before and after liposome addition, respectively. Peptide–liposome interaction increases FRET (F0/F) as a result of tryptophan quenching.

Patch-clamp recording

Whole-cell Ba2+ currents or Ca2+ currents were recorded at room temperature (20–24°C) using an EPC-10 amplifier with pulse software (HEKA). Electrodes were pulled from glass micropipette capillary (Sutter Instrument) to yield pipettes with resistances of 2–2.5 MΩ. Series-resistance errors were compensated at >60%, and fast and slow capacitance were compensated before the applied test-pulse sequences. Voltage-clamp records were acquired at 10 kHz and filtered at 3 kHz. For all recordings, cells were held at −80 mV. All data presented here are leak and capacitance subtracted before analysis. The external Ringer’s solution contained 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM BaCl2 or CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 8 mM glucose; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The internal solution of the pipette consisted of 175 mM CsCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA), 3 mM Na2ATP, and 0.1 mM Na3GTP; the pH was adjusted to 7.5 with CsOH. Reagents were obtained as follows: CsOH, BAPTA, Na2ATP, and Na3GTP (Sigma-Aldrich), and other chemicals (MERCK).

Curve fitting

Voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation was fitted by the following equation:

where I is the CaV2.2 current amplitude measured during the test pulse at 10 mV (at −10 mV for CaV1.3 channel) for conditioning depolarizations varying from −70 to 70 mV, Imax is the maximal current, V is the conditioning depolarization, V50,inact is the half-maximal voltage for current inactivation, R is the proportion of non-inactivating current, and K is a slope factor.

Confocal imaging

TsA201 cells were imaged 24–48 h after transfection on poly-l-lysine–coated coverslips with a confocal microscope (LSM 700; Carl Zeiss). Cell images were scanned by using a 40× (water) apochromatic objective lens at 1,024 × 1,024 pixels using digital zoom. For time courses, 524 × 524 pixels were used. During time course experiments, images were taken every 5 s in imaging software (ZEN; Carl Zeiss). Analysis of line scanning and quantitative analysis of the cytosolic or the plasma membrane fluorescence of target proteins were performed using the “profile” and the “measure” tools, respectively, in ZEN 2012 lite imaging software for region of interest (Carl Zeiss). All images were stored in LSM4 format, which is like JPEG, and raw data from time course was processed with Excel 2012 (Microsoft) and summarized in Igor Pro (WaveMetrics). For β-subunit localization analysis, the colocalization coefficient module in ZEN software was used for quantifying the colocalization between the various β subunits labeled with GFP and the PIP2 probe PH-PLCδ-RFP (PH-RFP) as a marker of the plasma membrane. Threshold intensities for each fluorescent protein were determined using the plasma membrane region of the images, and the overlap coefficient in the ZEN software was used as an indicator of colocalization coefficient.

Chemicals

2-Bromopalmitic acid and 2-hydroxymyristic acid were prepared as 100-mM stock solutions in DMSO and stored at −20°C. To make working concentrations of 100 µM, working solutions were prepared by diluting the stock at 1:1,000 with Ringer’s solution. Oxotremorine-M (Oxo-M) was dissolved in sterile water to make a 10-mM stock solution and was diluted further at 1:1,000 in Ringer’s solution for a working solution. Rapamycin was dissolved in DMSO to make a 1-mM stock solution and was diluted at 1:1,000 in Ringer’s solution. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

RESULTS

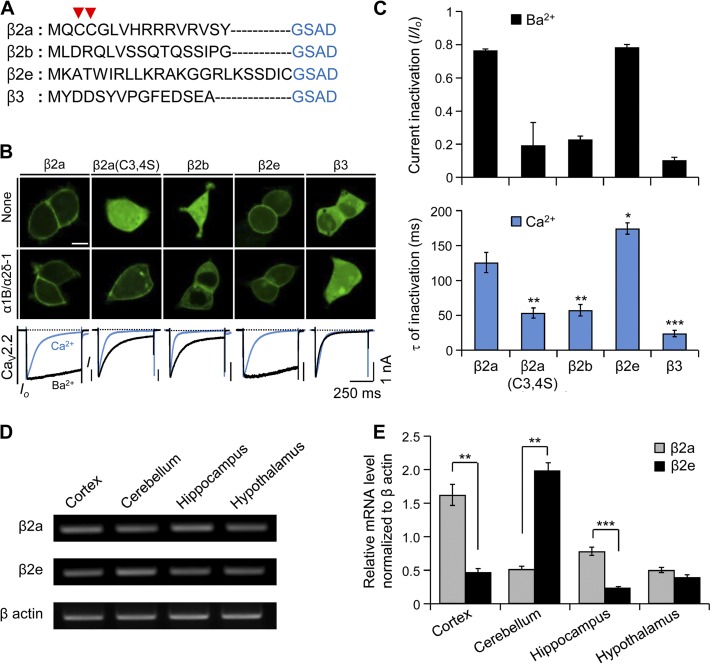

The β2e subunit is localized on the plasma membrane and is widely expressed

Without α1 subunits to bind to, most β subunits are cytosolic proteins, whereas because of palmitoylation of two cysteines, the β2a subunit expresses at the plasma membrane (Fig. 1, A and B). Similarly, as shown in Fig. 1 (B and C), the β2e subunit shows a membrane distribution and slows inactivation of CaV2.2 channels whether with 10 mM Ba2+ or 10 mM Ca2+ in the Ringer’s solution. In the Ca2+ Ringer’s solution, inactivation of CaV2.2 current is faster with all types of β subunits than in Ba2+ (Fig. 1 B, bottom), probably through Ca2+-dependent inactivation via interaction of its C terminus with calmodulin (Liang et al., 2003; Wykes et al., 2007). Even in the presence of Ca2+ ions, a slower inactivation is detected in channels with β2a and β2e subunits (Fig. 1 C, bottom). We then investigated relative mRNA expression profiles of β2e subunits in different mouse brain tissues. Previous studies showed that all β-subunit isoforms are expressed in the central nervous system (Ludwig et al., 1997; Dolphin, 2003; Schlick et al., 2010). Using qRT-PCR, we observed that like the β2a subunit, the β2e subunit is expressed in cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and hypothalamus (Fig. 1 D). Notably, in cerebellum, the β2e subunit was expressed at a fourfold higher level compared with the β2a subunit, whereas β2a is highly expressed in the rest of brain tissues (Fig. 1 E). The results indicate that the β2e subunit is localized at the plasma membrane in the presence or absence of α1 subunits and is expressed widely in the brain.

Figure 1.

Subcellular localization of different β subunits in tsA201 cells and mRNA expression of β2a and β2e subunits in brain tissues. (A) Amino acid multi-alignment of the N-terminal region of various β subunits. Arrow heads indicate two cysteine residues responsible for the palmitoylation and membrane binding of the β2a subunit. (B) Confocal images showing subcellular distribution of β subunits in the absence (top) or presence of α1B and α2δ-1 subunits in tsA 201 cells (middle). Current inactivation of CaV2.2 channels with different β subunits (bottom) was recorded during a 500-ms test pulse at 10 mV. Blue and black curves indicate Ca2+ currents and Ba2+ currents, respectively. Bar, 10 µm. (C) Summary of current inactivation of Ba2+ currents (top) and time constant (τ) for current inactivation of Ca2+ currents (bottom). Current inactivation (I/Io) was calculated as current amplitude (I) divided by initial peak amplitude (Io). For Ba2+ currents, β2a (n = 5), β2a(C3,4S) (n = 5), β2b (n = 5), β2e (n = 6), or β3 (n = 6); for Ca2+ currents, β2a (n = 4), β2a(C3,4S) (n = 6), β2b (n = 5), β2e (n = 5), or β3 (n = 5). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, compared with β2a. (D) mRNA expression of β2e subunit in cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and hypothalamus. mRNA expression of β actin was used as a positive control. (E) qRT-PCR mRNA expression profile for β2e and β2e subunits in cortex (n = 3), cerebellum (n = 3), hippocampus (n = 3), and hypothalamus (n = 3). mRNA expression levels of β2a and β2e subunits were normalized to the mRNA level of β actin. n = 3. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, compared with β2a. Data are mean ± SEM.

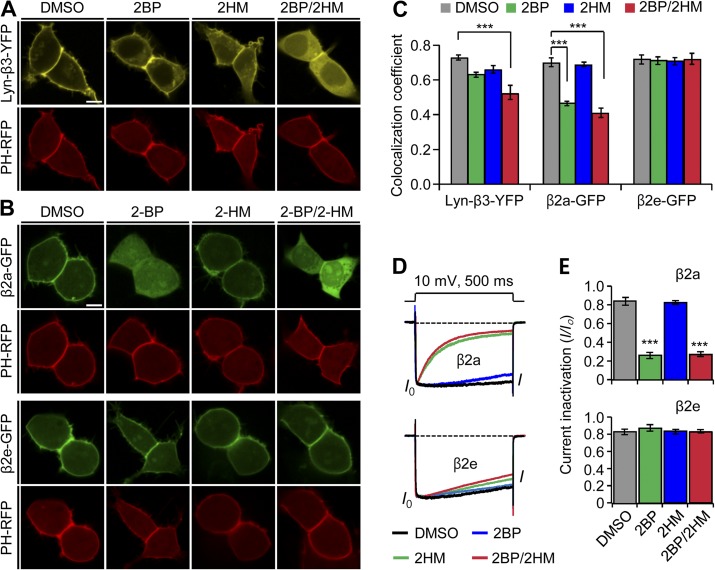

Membrane targeting of β2e subunit is independent from lipid modification

Several previous studies showed that lipidation of the β2a subunit can be blocked by inhibitors such as 2-bromopalmitate (2BP) and tunicamycin, leading to a cytosolic distribution of the protein and restoring fast inactivation to the channels (Hurley et al., 2000; Webb et al., 2000). In addition to palmitoylation, myristoylation can target peripheral proteins to membranes. Accordingly, we began by testing whether lipidation accounts for membrane localization of the β2e subunit using two types of inhibitors: 2BP for palmitoylation and 2-hydroxymyristate (2-HM) for myristoylation. As a positive control, we used a chimeric Lyn-β3-YFP construct known to be localized on the plasma membrane through both palmitoylation and myristoylation (Inoue et al., 2005). The confocal images for this Lyn control show that in the absence of α1, treatment with either lipidation inhibitor or both inhibitors together induces a cytosolic distribution of Lyn-β3-YFP, as predicted (Fig. 2 A). To quantify the localization of β subunits in the plasma membrane, we sampled cells expressing Lyn-β3-YFP and the membrane PIP2 probe PH-RFP in a blinded manner and calculated colocalization coefficients. The analysis shows that colocalization of two proteins decreases slightly in cells treated with 2BP or 2-HM and more in cells treated with both inhibitors (Fig. 2 C), confirming that Lyn targeting to the plasma membrane uses both myristoylation and palmitoylation. The β2a subunit was localized to the cytoplasm only when 2BP was added (Fig. 2, B and C). Additionally, inactivation of CaV channels was dramatically accelerated in cells treated with 2BP or both inhibitors (Fig. 2, D and E, top panels). On the other hand, with the β2e subunit, no combination of inhibitors had any effect on the subcellular distribution or the current inactivation (Fig. 2, B–E, bottom panels of D and E). These results suggest that unlike the membrane localization of the β2a subunit, membrane targeting of the β2e subunit does not depend on lipid modification.

Figure 2.

The N-terminal 23 amino acids determine the plasma membrane localization of the β2e subunit. (A) Confocal images of Lyn-β3-YFP–expressed cells. The PIP2 probe PH-PLCδ-RFP (PH-RFP) was cotransfected as a marker of the plasma membrane. Lyn-β3-YFP–expressed cells were preincubated with inhibitors for 12 h after transfection. Confocal images were taken by confocal microscope in the presence of vehicle (0.2% DMSO); a palmitoylation inhibitor, 2-BH (100 µM); a myristoylation inhibitor, 2-HM (100 µM); or both 2-BH and 2-HM. Bar, 5 µm. (B) Effect of lipidation inhibitors on subcellular localization of β2a (top) and β2e subunits (bottom). Cells expressing β2e subunit or β2e subunit were preincubated in the absence or presence of 100 µM 2-BH, 100 µM 2-HM, or both and were imaged by confocal microscope 24 h after transfection. Note that the β2e location was not affected by the inhibitors. Bar, 5 µm. (C) Quantification of membrane localization of Lyn-β3 (n = 8), β2a (n = 10), and β2e (n = 10) subunits compared with PH-RFP. The colocalization coefficients were obtained from merged images of Lyn-β3 and PH-RFP, β2a and PH-RFP, or β2e and PH-RFP, as shown in A and B. ***, P < 0.001, compared with DMSO. (D) Effect of lipidation inhibitors on current inactivation of CaV2.2 channels with β2a (top) or β2e subunits (bottom). Currents were measured during 500-ms test pulses to 10 mV. (E) Summary of current inactivation with β2a (top) and β2e (bottom) subunits. n = 4–6 for β2a; n = 4–5 for β2e. ***, P < 0.001, compared with DMSO. Data are mean ± SEM.

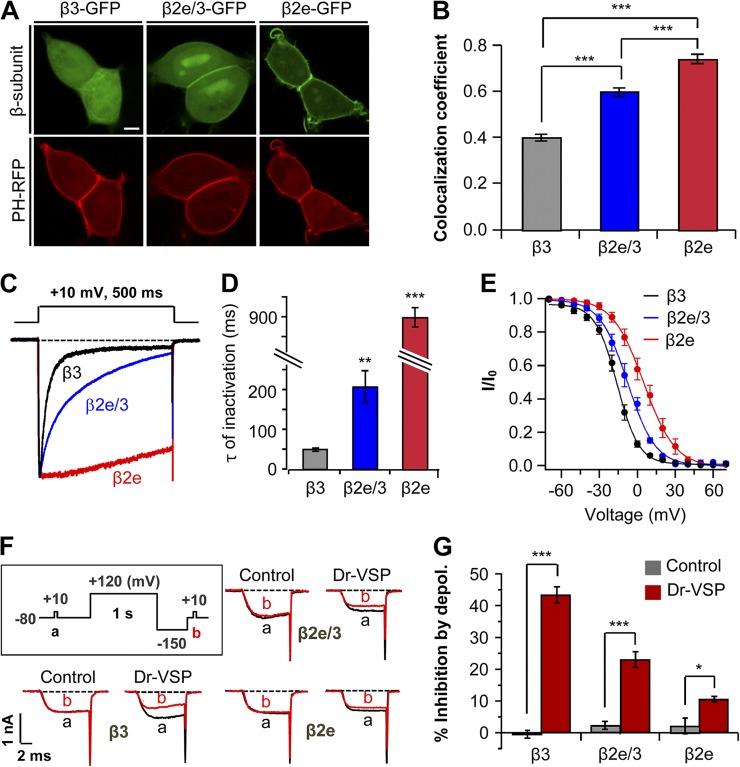

The N-terminal 23 amino acids determine the plasma membrane localization of the β2e subunit

As the β2 subunit splice variants differ only in their N-terminal region (Fig. 1 A), we examined whether the N terminus of the β2e subunit is a major determinant for membrane localization. We engineered a chimeric construct. The 23 N-terminal residues (MKATWIRLLKRAKGGRLKSSDIC) of the β2e subunit replaced the N terminus of the cytosolic β3 subunit (β2e/3). In the absence of α1, the chimeric constructs now expressed, in part, on the plasma membrane. However, they were also present in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 3 A). This incomplete targeting led us to consider that other domains of β2e also contribute to the membrane localization. Localization analysis indicated that the colocalization coefficient of β2e/3 subunit is intermediate between that of β3 and β2e subunits and significantly different from either (Fig. 3 B). Furthermore, the chimeric β2e/3 subunit attenuated inactivation of CaV2.2 current about fourfold compared with the cytosolic β3 subunit (Fig. 3, C and D). It has been reported previously that membrane anchoring of β subunits shifts the voltage dependence of inactivation to more depolarized voltages, whereas cytosolic β subunits shift to more hyperpolarized voltages (Buraei and Yang, 2010). Indeed, our results show that the midpoints (V50,inact) of steady-state inactivation with β3 and β2e subunits are −15.9 ± 0.5 mV and 5.1 ± 0.5 mV, respectively, and V50,inact of chimeric β2e/3 subunit is −7.7 ± 0.6 mV (Fig. 3 E).

Figure 3.

Subcellular localization of β subunits affects inactivation and PIP2 sensitivity of CaV channels. (A) Confocal images of cells expressing β3-GFP, chimeric β2e/3-GFP (β3 subunit containing β2e N-terminal 23 amino acids), and β2e-GFP with membrane PIP2 probe PH-PLCδ-RFP (PH-RFP). Bar, 5 µm. (B) Quantification of plasma membrane localization of β3-GFP, chimeric β2e/3-GFP, and β2e-GFP subunits. ***, P < 0.001. (C) Effect of membrane-anchored β2e/3-GFP on the inactivation of CaV2.2 currents. Currents were measured during 500-ms test pulses to 10 mV in cells expressing CaV2.2 channels with β3, β2e/3-GFP, or β2e subunits. (D) Summary of time constant (τ) for CaV2.2 current inactivation with β3 (n = 4), β2e/3 (n = 4), and β2e (n = 5) subunits. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, compared with β3. (E) Voltage dependence of normalized steady-state inactivation for CaV2.2 channels with β3 (n = 5), chimeric β2e/3 (n = 6), and β2e (n = 6) subunits. Normalized data were plotted against the conditioning potential. (F) Test protocol for depolarizing pulse and current inhibition of CaV2.2 channels with β3, β2e/3 and β2e subunits by Dr-VSP. The currents before (a) and after (b) a depolarizing pulse to 120 mV were superimposed in control and Dr-VSP transfected cells. (G) Summary of CaV2.2 current inhibition by membrane depolarization in control and Dr-VSP-expressing cells. For control, β3 (n = 5), β2e/3 (n = 4) or β2e (n = 5); for Dr-VSP, β3 (n = 4), β2e/3 (n = 4) or β2e (n = 5). * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, compared with control. Data are mean ± SEM.

In addition to the inactivation, β subunits regulate the PIP2 sensitivity of CaV channels (Suh et al., 2012). To investigate lipid modulation, we depleted PIP2 using the voltage-sensitive lipid phosphatase Dr-VSP, which can convert PIP2 to phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI(4)P) during depolarizing voltage pulses (Yeung et al., 2008; Suh et al., 2010). We asked whether the membrane-targeted chimeric β2e/3 subunit reduces the sensitivity to membrane PIP2 depletion. With Dr-VSP, PIP2 depletion by a 120-mV depolarizing pulse inhibited CaV2.2 current with the chimeric β2e/3 subunit by 24 ± 3%, less than with the cytosolic β3 subunit (43 ± 3%), but more than with β2e subunit (10 ± 1%; Fig. 3, F and G). This result suggests that the N-terminal region of β2e determines not only membrane targeting and slow inactivation but also low PIP2 sensitivity. Such data are consistent with our previous finding that localization of the β subunit is a key determinant both for the inactivation kinetics of CaV channels and for regulation by PIP2 depletion (Chan et al., 2007).

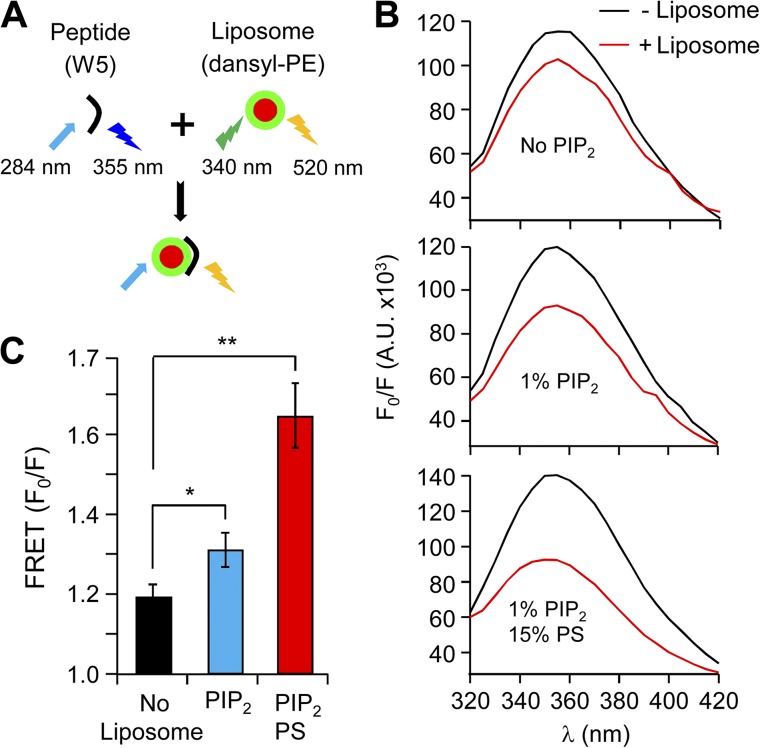

Phospholipids determine the binding affinity of peptides to liposomes

Neutralization of positive residues in the N terminus by mutagenesis relocated β2e subunits to the cytoplasm. To further investigate the mechanism for binding to the plasma membrane, we used a peptide-to-liposome FRET assay. This FRET approach measures the change of the peptide Trp fluorescence associated with proximity to liposome membranes. In the experiment, a 23-residue peptide of the N terminus of the β2e subunit (MKATWIRLLKRAKGGRLKSSDIC) was synthesized. Trp (W) served as the energy donor, and dansyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (dansyl-PE) was the energy acceptor. Quenching of Trp fluorescence was monitored using excitation (λex) at 284 nm and emission (λem) at 355 nm (Fig. 4 A). We first measured FRET with liposomes lacking anionic phospholipids (no PIP2). When liposomes were added to the peptide, the intensity of Trp fluorescence showed only a minor attenuation, indicating at best a weak hydrophobic peptide–liposome interaction (Fig. 4 B). However, when 1% PIP2 was present in the liposome membranes, there was a marked decrease of Trp fluorescence, indicating significant binding of N-terminal peptides to these liposomes. When 1% PIP2 and 15% PS were present in the liposome membranes, there was an additional reduction of Trp fluorescence, confirming that anionic phospholipids increase the binding of N-terminal peptides to liposome membranes. (Fig. 4, B and C). These results suggest that PIP2 as well as PS mediate the membrane binding of the β2e subunit to the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

Binding of the N-terminal peptide of β2e to liposomes is strengthened in the presence of anionic poly-PIs. (A) Schematic diagram of FRET analysis. Binding was examined using FRET between peptide containing Trp (W) (donor) and liposomes labeled with dansyl-PE (acceptor). Fluorescence emitted from Trp is quenched by dansyl-PE, suggesting peptide binding to liposomes. The initial spectrum of Trp was determined in the absence of liposomes (F0), and the subsequent spectrum was recorded after liposome addition (F). (B) FRET signals in the absence (black trace) or presence (red traces) of liposomes with no-liposome, 1% PIP2, or both 1% PIP2 and 15% PS. FRET is presented as F0/F at 355 nm. A.U., absorbance units. (C) Summary of FRET changes with different lipid compositions on the liposomes. For no-liposome, 1% PIP2, and both 1% PIP2 and 15% PS, n = 3; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, compared with no liposome. Data are mean ± SEM.

Depletion of poly-PIs induces cytosolic translocation of β2e subunits and fast channel inactivation

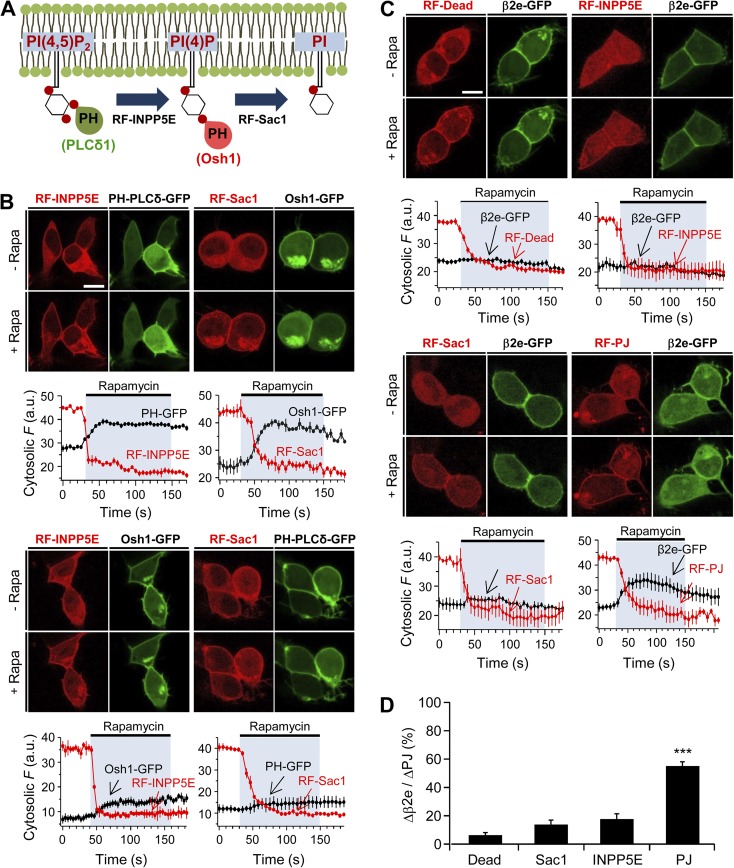

In recent studies with rapamycin-translocatable enzyme systems, it was reported that membrane recruitment of a lipid 4-phosphatase (Sac), a lipid 5-phosphatase (INPP5E), or pseudojanin (PJ; which has both Sac and INPP5E) can trigger the dissociation of peripheral membrane proteins from the plasma membrane inner surface (Hammond et al., 2012). Thus, PI(4)P and/or PIP2 function as anchors recruiting proteins to the membrane. We applied these tools to observe whether a direct depletion of poly-PIs can cause the dissociation of the β2e subunit from the cell membrane. For convenience, we will call these translocatable phosphatases RF-Sac, RF-INPP5E, and RF-PJ. We first verified the PI specificity of each translocatable enzyme and lipid probe (Fig. 5 A). As expected, recruitment of RF-Sac and RF-INPP5E to the plasma membrane by rapamycin evoked dissociation of the PI(4)P probe Osh1-GFP and of the PIP2 probe PH-PLCδ-GFP from the membrane, respectively (Fig. 5 B, top). It was proposed previously that Osh1 can also bind to PIP2 as well as to PI(4)P (Roy and Levine, 2004). Indeed, membrane recruitment of RF-INPP5E also caused a slight movement of Osh1-GFP to the cytosol, whereas Sac recruitment did not affect the PH-PLCδ-GFP (Fig. 5 B, bottom). Using these constructs, we examined whether lipid depletion can change the binding properties of β2e to the membrane in the absence of α1 subunits. Fig. 5 C shows confocal images of β2e-GFP and RF-enzymes before and after a 2-min application of 1 µM rapamycin. The results show that membrane translocation of either RF-INPP5E or RF-Sac alone is not enough to trigger the dissociation of β2e subunits from the plasma membrane (Fig. 5 C, top). However, when the RF-PJ was recruited to the membrane, it evoked a strong movement of β2e to the cytosol (Fig. 5, C, bottom, and D), suggesting that β2e subunits use both PI(4)P and PIP2 as plasma membrane anchors.

Figure 5.

Depletion of PI(4)P and PIP2 induces the dissociation of β2e subunit from the plasma membrane. (A) Schematic diagram of a depletion of PI(4)P or PIP2 by 4- or 5-phosphatases. (B) Confocal images and full time courses of cytosolic fluorescence change in cells transfected with LDR, PH-PLCδ-GFP, Osh-1-GFP, RF-INPP5E, and RF-Sac. Translocation of RF-INPP5E or RF-Sac to the plasma membrane by rapamycin depletes PH-PLCδ-GFP (PIP2 probe) or Osh1-GFP (PI(4)P probe), respectively. For INPP5E, n = 3; for Sac, n = 3. Bottom images show that plasma membrane translocation of RF-INPP5E or RF-Sac by rapamycin has no effect on depletion of Osh1-GFP or PH-PLCδ-GFP probes, respectively. For INPP5E, n = 3; for Sac, n = 3. Time courses were taken every 5 s by confocal microscope. Bar, 10 µm. (C) Confocal images and full time course of cytosolic fluorescence change in cells transfected with LDR, β2e-GFP, and RF-Dead (RFP-FKBP-dead form of PJ), RF-INPP5E, RF-Sac, and RF-PJ. Confocal images show the subcellular distribution of β2e-GFP and translocatable RF-phosphatases before and after rapamycin (1 µM) application for 2 min. For Dead, n = 4; for INPP5E, n = 3; for Sac, n = 3; for PJ, n = 4. Bar, 10 µm. (D) Change in cytosolic intensity of β2e subunit (Δβ2e) to cytosolic intensity of each translocatable enzyme (ΔPJs) before and after rapamycin application and expressed as percentage with Dead (n = 5), Sac (n = 5), INPP5E (n = 5), and PJ (n = 6). ***, P < 0.001, compared with Dead. Data are mean ± SEM.

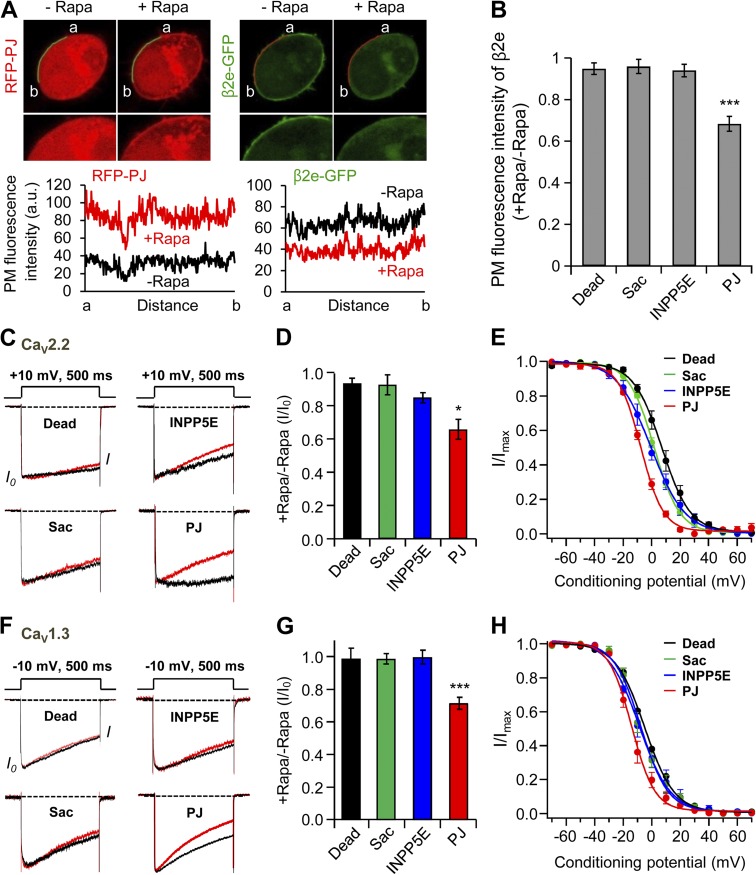

In addition to measuring the cytosolic fluorescence intensity of β2e subunits, we also analyzed the plasma membrane distribution of β2e before and after rapamycin application. Fig. 6 A shows that recruiting PJ to the plasma membrane by rapamycin application simultaneously induces a robust increase of fluorescence intensity of RFP-PJ at the plasma membrane and a decrease of fluorescence of β2e-GFP. Indeed, only the PJ but not the other translocatable enzymes decreased the presence of β2e at the plasma membrane (Fig. 6 B). Next, we tested the effects of poly-PI depletion on regulation of CaV2.2 channels coexpressed with the β2e subunit. As shown in Fig. 6 C is that depletion of PI(4)P or PIP2 by RF-INPP5E and RF-Sac systems had no significant effect on CaV2.2 current inactivation. In contrast, depletion of both lipids by the translocatable PJ system resulted in a stronger and faster current inactivation (Fig. 6, C and D).

Figure 6.

Depletion of PI(4)P and PIP2 accelerates current inactivation of CaV2.2 channels. (A) Analysis of plasma membrane fluorescence intensity of PJ and β2e. Left and right images show the plasma membrane distribution of RFP-PJ and β2e-GFP, respectively, before and after rapamycin addition for 2 min. Bottom and right plots indicate the fluorescence intensity of region of interest (ROI) in RFP-PJ –expressing cells and the intensity of ROI in β2-GFP–expressing cells, respectively, before and after rapamycin addition. (B) Summary of plasma membrane fluorescence intensity of the β2e subunit. Plasma membrane fluorescence intensity of β2e subunit for Dead, INPP5E, Sac, and PJ was normalized against the plasma membrane fluorescence intensity before rapamycin addition. For Dead, n = 7; for INPP5E, n = 7; for Sac, n = 8; for PJ, n = 8. ***, P < 0.001, compared with Dead. (C) Current inactivation of CaV2.2 channels with various translocatable systems were measured during a 500-ms test pulse at 10 mV. Current traces before (black trace) and after (red trace) rapamycin application are scaled to the peak current amplitude (I0) and superimposed. Dashed line indicates zero currents. (D) Summary of inactivation of CaV2.2 currents before and after rapamycin addition in cells expressing different translocatable dimerization constructs (n = 4–5). *, P < 0.05, compared with Dead. (E) Voltage dependence of normalized steady-state inactivation for CaV2.2 channels with Dead (n = 4), Sac (n = 4), INPP5E (n = 5), or PJ (n = 5) after rapamycin addition. (F) Effect of various translocatable systems on inactivation of CaV1.3 channels. CaV1.3 currents were measured during a 500-ms test pulse to −10 mV. (G) Summary of inactivation of CaV1.3 currents before and after rapamycin addition in cells expressing different translocatable dimerization constructs (n = 4–5). ***, P < 0.001, compared with Dead. (H) Voltage dependence of normalized steady-state inactivation for CaV1.3 channels with Dead (n = 4), Sac (n = 5), INPP5E (n = 5), or PJ (n = 5) after rapamycin addition. Data are mean ± SEM.

With the inactive enzyme PJ-Dead, V50,inact of steady-state inactivation of CaV2.2 channel was 7.1 ± 0.4 mV. Depletion of both PI(4)P and PIP2 by PJ shifted the voltage dependence of inactivation to more negative voltages (V50,inact = −7.8 ± 0.3 mV), and depletion of PI(4)P or PIP2 shifted somewhat less (V50,inact = 1.8 ± 0.3 mV and −0.5 ± 0.4 mV, respectively; Fig. 6 E). We also tested the effects of depleting poly-PI on gating of CaV1.3 channels. Only PJ accelerated the inactivation of CaV1.3 channel significantly (Fig. 6, F and G). Like the voltage dependence of inactivation for the CaV2.2 channel, depletion of both PI(4)P and PIP2 caused the voltage dependence of inactivation to be more negative (V50,inact = −14.1 ± 0.7 mV) compared with that of Dead (V50,inact = −4.8 ± 0.5 mV). The depletion of PI(4)P (V50,inact = −8.7 ± 0.9 mV) or PIP2 (V50,inact = −7.7 ± 0.7 mV) was intermediate (Fig. 6 H). These results suggests that PI(4)P and PIP2 together determine current inactivation of CaV2.2 and CaV1.3 channels with the β2e subunit.

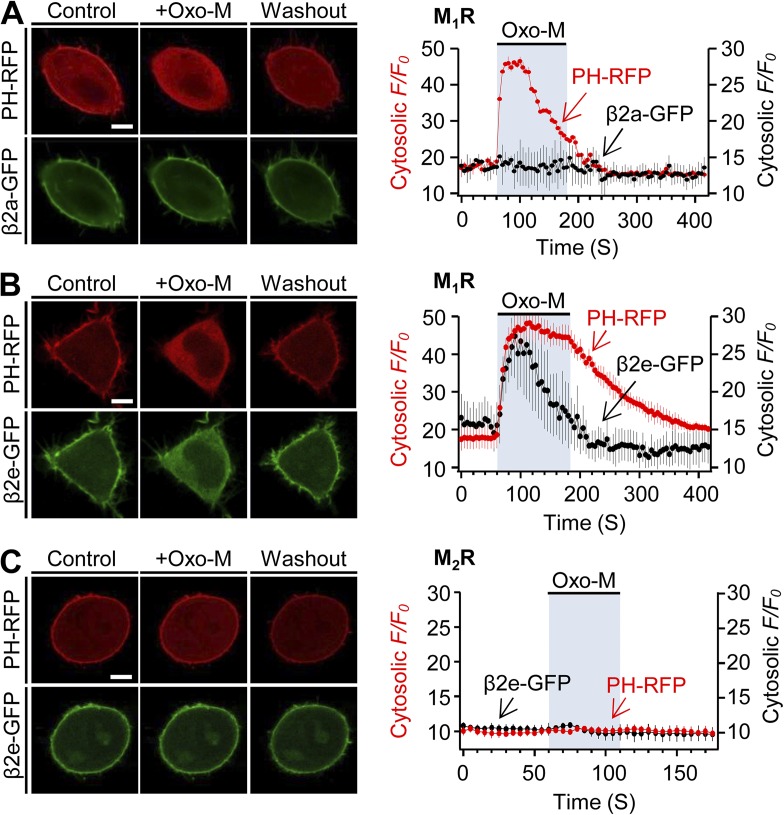

M1 receptor activation results in fast inactivation of CaV current by eliciting transient and reversible translocation of β2e subunit from membrane to cytosol

Activation of GqPCRs including M1Rs or AT1a angiotensin receptors depletes both PI(4)P and PIP2 in the plasma membrane via the activation of PLCβ (Horowitz et al., 2005; Balla et al., 2008). Based on Fig. 4, we examined whether M1R activation has any effect on localization of the β2e subunit in the absence of α1 subunits. When the M1R is activated by Oxo-M, the PH-PLCδ-RFP probe but not the lipidated β2a subunit migrated to the cytosol (Fig. 7 A). Hence, even when PIP2 and PI(4)P are depleted by M1R, the β2a subunit stays in the membrane through its palmitoylation. However, in β2e-transfected cells, M1R activation induced strong translocation of both PH-PLCδ-RFP and β2e-GFP simultaneously (Fig. 7 B). We also tested the specificity of G protein–coupled receptors using M2-muscarinic receptors (M2Rs), which are Gi/o protein coupled (Fig. 7 C). Activation of M2R by Oxo-M had no effect on translocation of the β2a subunit. Collectively, these results suggest that membrane binding of the β2e subunit relies on poly-PIs and PS in the plasma membrane, and that PI depletion by activation of M1R suffices for reversible translocation of the β2e subunit.

Figure 7.

Activation of M1R induces reversible translocation of the β2e subunit. Confocal images and full time courses of PH-PLCδ-RFP (PH-RFP) and β2a-GFP (A) or PH-RFP and β2e-GFP (B) before, during, and after Oxo-M (10 µM) application in M1R-expressing cells. Time courses were taken every 5 s by confocal microscope. (C) Subcellular distributions and a full time course of PH-RFP and β2e-GFP in M2R-expressing cells. For analysis of time course, n = 4–5. Scale bars, 10 µm.

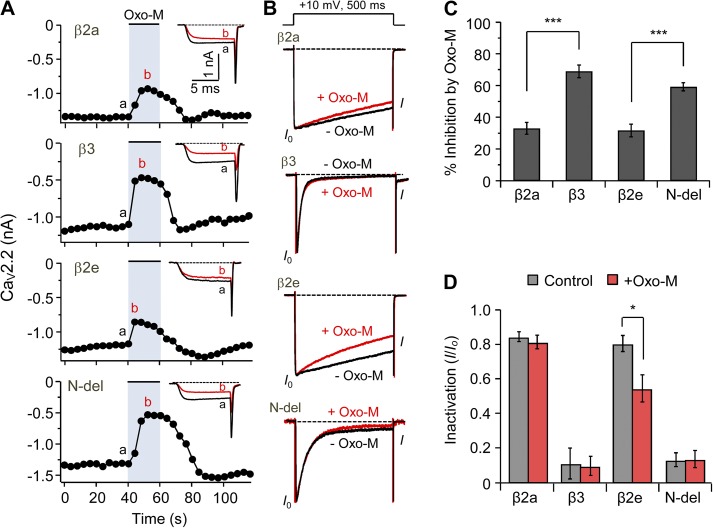

Next, we investigated the effect of the β2e subunit on the modulation of CaV2.2 channel gating by M1R. Previous studies showed that muscarinic stimulation inhibits current of CaV2.2 channels in a β subunit–dependent manner (Heneghan et al., 2009; Suh et al., 2012; Keum et al., 2014). As shown in Fig. 8 A, membrane-anchored β2a and β2e subunits show similar weak muscarinic suppression of the currents (34 ± 2% vs. 32 ± 4% for β2a and β2e, respectively), whereas two cytosolic β3 and N terminus–deleted (N-del) subunits show a stronger muscarinic suppression (69 ± 4% vs. 59 ± 3% for β3 and N-del, respectively; Fig. 8, A and C). Finally, we tested the effect of M1R on inactivation of CaV channels. Oxo-M treatment potentiated inactivation of CaV2.2 current in cells with the β2e subunit somewhat, whereas Oxo-M treatment had no significant effect on current inactivation in β2a, β3, and N-del subunits expressing cells (Fig. 8 B), consistent with an M1R-induced translocation of β2e to the cytosol (Fig. 8, B and D). Collectively, these results suggest that the subcellular redistribution of β2e subunits when GqPCRs deplete PI(4)P and PIP2 changes the gating of CaV channels.

Figure 8.

M1 muscarinic stimulation induces fast inactivation of CaV2.2 current by eliciting transient and reversible translocation of the β2e subunit from membrane to cytosol. (A) Current inhibition of CaV2.2 channels by M1R activation with Oxo-M and current inactivation of CaV2.2 channels before Oxo-M and during Oxo-M addition in cells expressing β2a, β3, β2e, or N-del. Current traces for before (a) and during (b) Oxo-M addition were superimposed (inset). (B) Current inactivation with various β subunits was recorded during a 500-ms test pulse at 10 mV. Current traces before (black trace) and during (red trace) Oxo-M applications were scaled to the peak current amplitude (I0) and were superimposed. Dashed line indicates zero currents. (C) Summary of CaV2.2 current inhibition by M1R stimulation in cells expressing β2a (n = 4), β3 (n = 6), β2e (n = 8), or N-del (n = 9). ***, P < 0.001, compared with β2a and β2e, respectively. (D) Summary of current inactivation before and during Oxo-M application in cells expressing β2a (n = 6), β3 (n = 5), β2e (n = 5), or N-del (n = 5). *, P < 0.05, compared with control. Data are mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

In 1996, the palmitoylation and plasma membrane localization of the β2a splice variant of β2 subunits were discovered (Chien et al., 1996). Those properties have functional consequences for CaV channels, including slowing inactivation kinetics and decreasing regulation by membrane phospholipids (Chien et al., 1998; Qin et al., 1998; Hurley et al., 2000; Heneghan et al., 2009; Suh et al., 2012). Like β2a, β2e was found to locate to the plasma membrane and to slow inactivation of CaV channels in HEK293 cells (Takahashi et al., 2003). Recently, interaction of the N-terminal basic residues of β2e with membrane PS was reported to play a role in tethering of the β2e subunit (Miranda-Laferte et al., 2014). Those studies suggested electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions with the membrane. We anticipated that the interactions between the β2e subunit and the membrane PI phospholipids might also be responsible for the dynamic regulation of CaV channels by G protein–coupled receptors.

Our study focused on the interaction between the β2e subunit and membrane poly-PIs and how this affects CaV channel gating and modulation in living cells. We took advantage of three rapamycin-inducible dimerization tools containing lipid phosphatases (Hammond et al., 2012). Binding of the β2e subunit to the membrane could be reversed by depleting poly-PI with the lipid phosphatases or with direct GqPCR activation. Recruiting either the 4- or 5-phosphatase alone to the membrane had little effect on β2e localization, but recruiting PJ, which combines both phosphatases, released the β2e subunit from the plasma membrane. Thus, we infer that the β2e subunit binds PI(4)P and PIP2, and that depleting both lipids allows dissociation of the β2e subunit from the membrane. These results are reminiscent of findings that PI(4)P and PIP2 activate TRPV1 channels with similar potency (Hammond et al., 2012; Lukacs et al., 2013). Membrane PI(4)P can be involved in scaffolding, recruiting peripheral proteins to the membrane, activation of ion channels, and as a precursor for PIP2 synthesis (Suh and Hille, 2008; Korzeniowski et al., 2009; Balla, 2013). Although membrane PI(4)P works together with PIP2 to recruit the intact β2e subunit to the plasma membrane, our FRET analysis using only the N-terminal peptide and model liposomes shows that including sufficient PIP2 suffices for significant interaction between N-terminal peptide and the liposome. Additionally, Miranda-Laferte et al. (2014) showed that including PS augments β2e binding to liposomes compared with neutral (phosphatidylcholine) liposomes. It seems that PI(4)P and PIP2 play a major role in membrane targeting of the β2e subunit (see also Cho and Stahelin, 2005; Mulgrew-Nesbitt et al., 2006), but other anionic phospholipids can contribute as well—this might be called a nonspecific interaction.

In addition to the rapamycin-translocatable enzymes, we used activation of M1R, whose well-characterized pathway results in depletion of PI(4)P and PIP2 (Horowitz et al., 2005; Balla et al., 2008). The results showed a striking dynamic action on the β2e subunit. As shown in Fig. 7 with M1R, we found that receptor activation induces translocation of the β2e subunit, thus altering CaV channel gating dynamically. Again, this shows that poly-PIs are essential to guarantee membrane localization in the cell. Because we cannot deplete PS acutely, we cannot rule out that PS also contributes an important component of the interaction energy.

From the standpoint of the neuron, all β subunits are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems (Vacher et al., 2008; Obermair et al., 2010; Schlick et al., 2010; Frank, 2014) and thus can play pivotal roles in homeostatic synaptic plasticity via regulation of CaV channel complexes (Catterall and Few, 2008; Simms and Zamponi, 2014). Although all β subunits associate with α1 subunits and share common features such as membrane trafficking of α1 and regulation of gating properties, the roles of β subunits in synaptic transmission depend on cellular context. Xie et al. (2007) reported a functional difference for β subunits in hippocampal neurons. They showed that β2a and β4b trigger synaptic vesicle depletion (depression) and paired-pulse facilitation, respectively. Because they slow inactivation, these β subunits enhance Ca2+ influx into the presynaptic nerve terminal, ultimately leading to change of transmitter release and synaptic plasticity. CaV1 channels are predominantly expressed in postsynaptic membranes (Lipscombe et al., 2004) and CaV2 channels in presynaptic terminals (Reid et al., 2003). In parallel qRT-PCR analysis with the β2a subunit, the β2e mRNA is expressed in various brain tissues such as cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and hypothalamus. Our finding is that depletion of both PI(4)P and PIP2 by M1R activation gives rise to reversible translocation of the β2e subunit, leading to fast inactivation. Therefore, given the abundance of expression of the β2e subunit in brain region, dynamic regulation of β2e location and differential regulation of current inactivation in CaV channels with β2a and β2e subunits by GqPCR-mediated PIP2 depletion ought to contribute a novel regulation of the synapse and of synaptic plasticity.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that plasma membrane poly-PIs contribute to membrane targeting of the β2e subunit through an electrostatic mechanism. The β2e subunit slows inactivation of CaV channels, but when poly-PIs are depleted by M1R activation, the β2e subunit shifts to the cytosol and channels show more inactivation. Such reversible membrane interaction unique to the β2e subunit invites speculation that dynamic regulation of the β2e subunit by depletion of membrane lipids is another mechanism for regulating function of CaV channels. Future work should reveal this regulatory mode in native neurons and investigate the physiological consequence of neuronal CaV channels in synaptic plasticity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Bertil Hille for valuable discussion. We thank many laboratories for providing the plasmids.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science & Technology (no. 2012R1A1A2044699) and the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT&Future Planning (no. 14-BD-06 to B.-C. Suh).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: B.-C. Suh designed the research; D.-I. Kim, Y. Park, and D.-J. Jang performed biochemical and electrophysiological research; D.-I. Kim and B.-C. Suh wrote the paper.

Kenton J. Swartz served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- 2BP

- 2-bromopalmitate

- 2-HM

- 2-hydroxymyristate

- CaV

- voltage-gated Ca2+

- FRET

- fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GqPCR

- Gq protein–coupled receptor

- M1R

- M1 muscarinic receptor

- N-del

- N terminus–deleted

- Oxo-M

- oxotremorine-M

- PI

- phosphoinositide

- PI(4)P

- phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PJ

- pseudojanin

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

References

- Altier C., Garcia-Caballero A., Simms B., You H., Chen L., Walcher J., Tedford H.W., Hermosilla T., and Zamponi G.W.. 2011. The Cavβ subunit prevents RFP2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of L-type channels. Nat. Neurosci. 14:173–180. 10.1038/nn.2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla A., Kim Y.J., Varnai P., Szentpetery Z., Knight Z., Shokat K.M., and Balla T.. 2008. Maintenance of hormone-sensitive phosphoinositide pools in the plasma membrane requires phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIalpha. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19:711–721. 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla T. 2013. Phosphoinositides: Tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 93:1019–1137. 10.1152/physrev.00028.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet D., Cornet V., Geib S., Carlier E., Volsen S., Hoshi T., Mori Y., and De Waard M.. 2000. The I-II loop of the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal antagonized by the β subunit. Neuron. 25:177–190. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80881-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z., and Yang J.. 2010. The β subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol. Rev. 90:1461–1506. 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W.A. 2000. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16:521–555. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W.A., and Few A.P.. 2008. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 59:882–901. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.W., Owens S., Tung C., and Stanley E.F.. 2007. Resistance of presynaptic CaV2.2 channels to voltage-dependent inactivation: Dynamic palmitoylation and voltage sensitivity. Cell Calcium. 42:419–425. 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien A.J., Carr K.M., Shirokov R.E., Rios E., and Hosey M.M.. 1996. Identification of palmitoylation sites within the L-type calcium channel β2a subunit and effects on channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 271:26465–26468. 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien A.J., Gao T., Perez-Reyes E., and Hosey M.M.. 1998. Membrane targeting of L-type calcium channels. Role of palmitoylation in the subcellular localization of the β2a subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23590–23597. 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho W., and Stahelin R.V.. 2005. Membrane-protein interactions in cell signaling and membrane trafficking. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 34:119–151. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.133337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colecraft H.M., Alseikhan B., Takahashi S.X., Chaudhuri D., Mittman S., Yegnasubramanian V., Alvania R.S., Johns D.C., Marbán E., and Yue D.T.. 2002. Novel functional properties of Ca2+ channel β subunits revealed by their expression in adult rat heart cells. J. Physiol. 541:435–452. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNitto J.P., Cronin T.C., and Lambright D.G.. 2003. Membrane recognition and targeting by lipid-binding domains. Sci. STKE. 2003:re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin A.C. 2003. β subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 35:599–620. 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000008026.37790.5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertel E.A., Campbell K.P., Harpold M.M., Hofmann F., Mori Y., Perez-Reyes E., Schwartz A., Snutch T.P., Tanabe T., Birnbaumer L., et al. 2000. Nomenclature of voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuron. 25:533–535. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81057-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C.A. 2014. How voltage-gated calcium channels gate forms of homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:40 10.3389/fncel.2014.00040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond G.R., Fischer M.J., Anderson K.E., Holdich J., Koteci A., Balla T., and Irvine R.F.. 2012. PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 are essential but independent lipid determinants of membrane identity. Science. 337:727–730. 10.1126/science.1222483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneghan J.F., Mitra-Ganguli T., Stanish L.F., Liu L., Zhao R., and Rittenhouse A.R.. 2009. The Ca2+ channel β subunit determines whether stimulation of Gq-coupled receptors enhances or inhibits N current. J. Gen. Physiol. 134:369–384. 10.1085/jgp.200910203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz L.F., Hirdes W., Suh B.C., Hilgemann D.W., Mackie K., and Hille B.. 2005. Phospholipase C in living cells: Activation, inhibition, Ca2+ requirement, and regulation of M current. J. Gen. Physiol. 126:243–262. 10.1085/jgp.200509309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J.H., Cahill A.L., Currie K.P., and Fox A.P.. 2000. The role of dynamic palmitoylation in Ca2+ channel inactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:9293–9298. 10.1073/pnas.160589697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T., Heo W.D., Grimley J.S., Wandless T.J., and Meyer T.. 2005. An inducible translocation strategy to rapidly activate and inhibit small GTPase signaling pathways. Nat. Methods. 2:415–418. 10.1038/nmeth763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keum D., Baek C., Kim D.I., Kweon H.J., and Suh B.C.. 2014. Voltage-dependent regulation of CaV2.2 channels by Gq-coupled receptor is facilitated by membrane-localized β subunit. J. Gen. Physiol. 144:297–309. 10.1085/jgp.201411245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzeniowski M.K., Popovic M.A., Szentpetery Z., Varnai P., Stojilkovic S.S., and Balla T.. 2009. Dependence of STIM1/Orai1-mediated calcium entry on plasma membrane phosphoinositides. J. Biol. Chem. 284:21027–21035. 10.1074/jbc.M109.012252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H., DeMaria C.D., Erickson M.G., Mori M.X., Alseikhan B.A., and Yue D.T.. 2003. Unified mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation across the Ca2+ channel family. Neuron. 39:951–960. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00560-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link S., Meissner M., Held B., Beck A., Weissgerber P., Freichel M., and Flockerzi V.. 2009. Diversity and developmental expression of L-type calcium channel β2 proteins and their influence on calcium current in murine heart. J. Biol. Chem. 284:30129–30137. 10.1074/jbc.M109.045583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscombe D., Helton T.D., and Xu W.. 2004. L-type calcium channels: The low down. J. Neurophysiol. 92:2633–2641. 10.1152/jn.00486.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A., Flockerzi V., and Hofmann F.. 1997. Regional expression and cellular localization of the α1 and β subunit of high voltage-activated calcium channels in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 17:1339–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs V., Yudin Y., Hammond G.R., Sharma E., Fukami K., and Rohacs T.. 2013. Distinctive changes in plasma membrane phosphoinositides underlie differential regulation of TRPV1 in nociceptive neurons. J. Neurosci. 33:11451–11463. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5637-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa E., Kelly K.M., Yule D.I., MacDonald R.L., and Uhler M.D.. 1995. Comparison of fura-2 imaging and electrophysiological analysis of murine calcium channel α1 subunits coexpressed with novel β2 subunit isoforms. Mol. Pharmacol. 47:707–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S., and Murray D.. 2005. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 438:605–611. 10.1038/nature04398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Laferte E., Ewers D., Guzman R.E., Jordan N., Schmidt S., and Hidalgo P.. 2014. The N-terminal domain tethers the voltage-gated calcium channel β2e-subunit to the plasma membrane via electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 289:10387–10398. 10.1074/jbc.M113.507244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulgrew-Nesbitt A., Diraviyam K., Wang J., Singh S., Murray P., Li Z., Rogers L., Mirkovic N., and Murray D.. 2006. The role of electrostatics in protein-membrane interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1761:812–826. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalefski E.A., and Falke J.J.. 2002. Use of fluorescence resonance energy transfer to monitor Ca2+-triggered membrane docking of C2 domains. Methods Mol. Biol. 172:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermair G.J., Schlick B., Di Biase V., Subramanyam P., Gebhart M., Baumgartner S., and Flucher B.E.. 2010. Reciprocal interactions regulate targeting of calcium channel β subunits and membrane expression of α1 subunits in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 285:5776–5791. 10.1074/jbc.M109.044271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N., Platano D., Olcese R., Costantin J.L., Stefani E., and Birnbaumer L.. 1998. Unique regulatory properties of the type 2a Ca2+ channel β subunit caused by palmitoylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:4690–4695. 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid C.A., Bekkers J.M., and Clements J.D.. 2003. Presynaptic Ca2+ channels: a functional patchwork. Trends Neurosci. 26:683–687. 10.1016/j.tins.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Crowley M.L., Mitra-Ganguli T., Liu L., and Rittenhouse A.R.. 2009. Regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by lipids. Cell Calcium. 45:589–601. 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., and Logothetis D.E.. 2007. Molecular characteristics of phosphoinositide binding. Pflugers Arch. 455:45–53. 10.1007/s00424-007-0291-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A., and Levine T.P.. 2004. Multiple pools of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate detected using the pleckstrin homology domain of Osh2p. J. Biol. Chem. 279:44683–44689. 10.1074/jbc.M401583200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlick B., Flucher B.E., and Obermair G.J.. 2010. Voltage-activated calcium channel expression profiles in mouse brain and cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 167:786–798. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms B.A., and Zamponi G.W.. 2014. Neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels: Structure, function, and dysfunction. Neuron. 82:24–45. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B.C., and Hille B.. 2008. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: How and why? Annu Rev Biophys. 37:175–195. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B.C., Leal K., and Hille B.. 2010. Modulation of high-voltage activated Ca2+ channels by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Neuron. 67:224–238. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B.C., Kim D.I., Falkenburger B.H., and Hille B.. 2012. Membrane-localized β-subunits alter the PIP2 regulation of high-voltage activated Ca2+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:3161–3166. 10.1073/pnas.1121434109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S.X., Mittman S., and Colecraft H.M.. 2003. Distinctive modulatory effects of five human auxiliary β2 subunit splice variants on L-type calcium channel gating. Biophys. J. 84:3007–3021. 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70027-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacher H., Mohapatra D.P., and Trimmer J.S.. 2008. Localization and targeting of voltage-dependent ion channels in mammalian central neurons. Physiol. Rev. 88:1407–1447. 10.1152/physrev.00002.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer G., Voelker D.R., and Feigenson G.W.. 2008. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:112–124. 10.1038/nrm2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waithe D., Ferron L., Page K.M., Chaggar K., and Dolphin A.C.. 2011. β-subunits promote the expression of CaV2.2 channels by reducing their proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 286:9598–9611. 10.1074/jbc.M110.195909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb Y., Hermida-Matsumoto L., and Resh M.D.. 2000. Inhibition of protein palmitoylation, raft localization, and T cell signaling by 2-bromopalmitate and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 275:261–270. 10.1074/jbc.275.1.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes R.C., Bauer C.S., Khan S.U., Weiss J.L., and Seward E.P.. 2007. Differential regulation of endogenous N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel inactivation by Ca2+/calmodulin impacts on their ability to support exocytosis in chromaffin cells. J. Neurosci. 27:5236–5248. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3545-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M., Li X., Han J., Vogt D.L., Wittemann S., Mark M.D., and Herlitze S.. 2007. Facilitation versus depression in cultured hippocampal neurons determined by targeting of Ca2+ channel Cavβ4 versus Cavβ2 subunits to synaptic terminals. J. Cell Biol. 178:489–502. 10.1083/jcb.200702072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung T., Gilbert G.E., Shi J., Silvius J., Kapus A., and Grinstein S.. 2008. Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science. 319:210–213. 10.1126/science.1152066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]