Abstract

Asthma is the most common chronic lower respiratory disease in childhood throughout the world. Several guidelines and/or consensus documents are available to support medical decisions on pediatric asthma. Although there is no doubt that the use of common systematic approaches for management can considerably improve outcomes, dissemination and implementation of these are still major challenges. Consequently, the International Collaboration in Asthma, Allergy and Immunology (iCAALL), recently formed by the EAACI, AAAAI, ACAAI and WAO, has decided to propose an International Consensus on (ICON) Pediatric Asthma. The purpose of this document is to highlight the key messages that are common to many of the existing guidelines, while critically reviewing and commenting on any differences, thus providing a concise reference.

The principles of pediatric asthma management are generally accepted. Overall, the treatment goal is disease control. In order to achieve this, patients and their parents should be educated to optimally manage the disease, in collaboration with health care professionals. Identification and avoidance of triggers is also of significant importance. Assessment and monitoring should be performed regularly to re-evaluate and fine-tune treatment. Pharmacotherapy is the cornerstone of treatment. The optimal use of medication can, in most cases, help patients control symptoms and reduce the risk for future morbidity. The management of exacerbations is a major consideration, independent from chronic treatment. There is a trend towards considering phenotype specific treatment choices; however this goal has not yet been achieved.

Introduction

Asthma is the most common chronic lower respiratory disease in childhood throughout the world. Asthma most often starts early in life and has variable courses and unstable phenotypes which may progress or remit over time. Wheeze in pre-school children may result from a number of different conditions; around half of preschool wheezers become asymptomatic by school age irrespective of treatment. However, asthma symptoms may persist, often for life, especially in atopic and more severe cases. The impact of asthma on the quality of life of patients, as well as its cost are very high. Therefore, appropriate asthma management may have a major impact in the quality of life of patients and their families, as well as on public health outcomes (1). Asthma in childhood is strongly associated with allergy, especially in developed countries. Common exposures such as tobacco smoke, air pollution and respiratory infections may trigger symptoms and contribute to the morbidity and occasional mortality. Currently, primary prevention is not possible. However, in established disease, control can be achieved and maintained with appropriate treatment, education and monitoring in most children.

In children, asthma often presents with additional challenges not all of which are seen in adults, due to the maturing of the respiratory and immune systems, natural history, scarcity of good evidence, difficulty to establish the diagnosis and deliver medications, and a diverse and frequently unpredictable response to treatment.

It is therefore not surprising that several guidelines and/or consensus documents are available to support medical decisions on pediatric asthma. These vary in scope and methodology, local, regional or international focus, or their exclusivity to pediatric asthma. Although there is no doubt that the use of common systematic approaches for management, such as guidelines or national programs, can considerably improve outcomes, dissemination and implementation of these recommendations are still major challenges.

For these reasons, the International Collaboration in Asthma, Allergy and Immunology (iCAALL) (2), formed in 2012 by the EAACI, AAAAI, ACAAI and WAO, helped organize an international writing group to address this unmet need with an International Consensus on (ICON) Pediatric Asthma. The purpose of this document is to highlight the key messages that are common to many of the existing guidelines, while critically reviewing and commenting on any differences, thus providing a concise reference.

Methodology

A working committee was formed and approved by the Steering Committee of iCAALL and the participating organizations (authors 1–11). The criteria used for the formation of the committee were: international representation, relevance to the field and previous participation in pediatric asthma guidelines. The members of the committee proposed relevant documents to be appraised. These were the Australian Asthma Management Handbook, 2006 (AAMH) (3), the Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, published by GINA and updated in 2011 (GINA) (4), and Global Strategy for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma in Children 5 Years and Younger, 2009 (GINA<5) (5), the Japanese Guideline for Childhood Asthma, 2008 (JGCA) (6), the National Heart and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma, 2007 (NAEPP) (7), the Diagnosis and treatment of Asthma in Childhood: a PRACTALL Consensus Report, 2008 (PRACTALL) (8) and the British Guideline on the Management of Asthma, Revised 2011 (SIGN) (9). Each member undertook responsibility for preparing tables and relevant commentaries comparing the included documents in a specific domain. These were subsequently compiled into a first draft which was circulated among the authors for comments and corrections. The revised document was then circulated among an independent reviewing group (authors 12–68), the comments of which were taken into account in the final draft, which was approved by the governing bodies of the participating organizations and submitted for publication. Recommendations were extrapolated from the reference documents and presented using Evidence levels (A–D) (10).

Definition and Classifications of Pediatric asthma

Definition

The complexity and diversity of asthma in both children and adults are indisputable and what is ‘true’ asthma is frequently argued, especially in childhood. Nevertheless, no guideline proposes a differentiation between pediatric and adult asthma in regard to the definition.

All current definitions are descriptive, including symptoms and their patterns, as well as underlying mechanisms, at different levels of detail. With only minor deviations in term usage, asthma is understood as a chronic disorder, presenting with recurrent episodes of wheeze, cough, difficulty in breathing and chest tightness, usually associated with variable airflow obstruction and bronchial (airway) hyperresponsiveness (BHR or AHR).

Chronic inflammation is recognized as the central pathology. In contrast, airway remodeling is only mentioned in the definition of the JGCA. The causal link(s) between chronic inflammation, BHR and symptoms are poorly defined; some definitions suggest that inflammation causes symptoms and BHR, others that BHR causes the symptoms, and yet others that this relationship is unclear.

Definitions often include more details, such as specific cells types (e.g. mast cells, eosinophils, etc.), timing of symptoms (particularly at night or early morning), reversibility (often) or triggers (viral infection, exercise, allergen exposure). The relative importance of each of these additional elements can be argued; nevertheless, they are neither necessary for, nor exclusive to asthma, therefore do not add appreciably to the sensitivity or specificity of the previously mentioned, generally accepted elements.

Taking the above into account, a working definition, representing a synopsis from all guidelines, is shown in Box 1.

Box 1 – Asthma definition.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder associated with variable airflow obstruction and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. It presents with recurrent episodes of wheeze, cough, shortness of breath, chest tightness.

Classifications

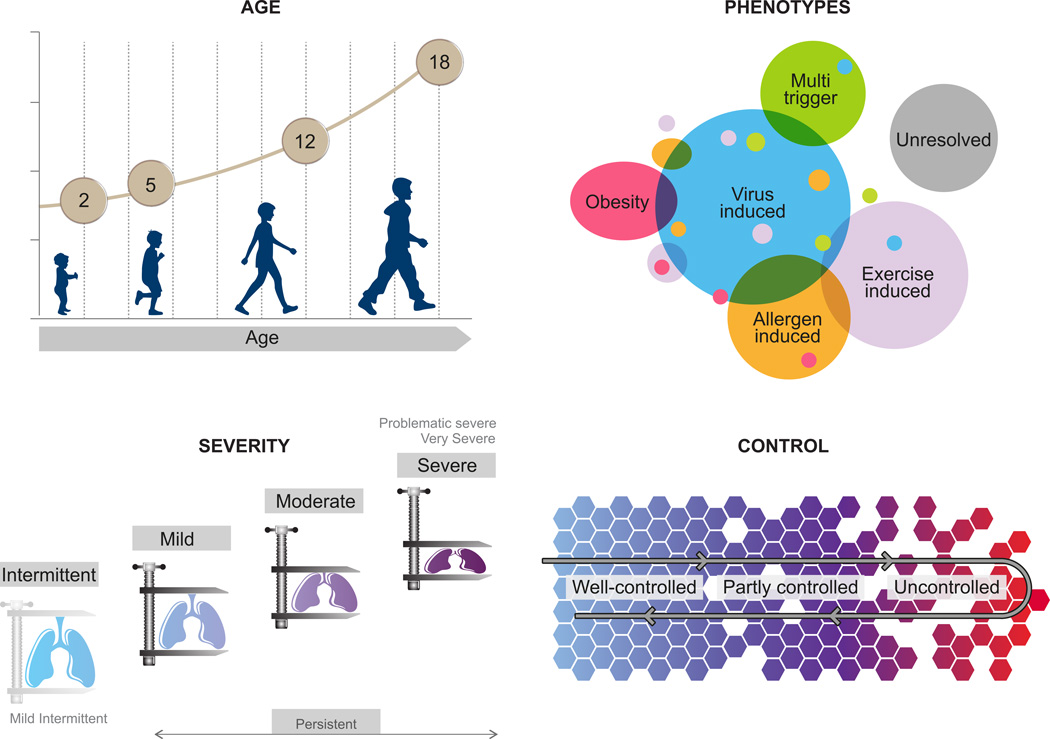

In order to address diversity and guide management, several factors have been used to classify pediatric asthma (Figure 1).

Age is an important classification factor, relevant for diagnosis and treatment. There is general consensus that milestone ages are around 5 and 12 years and important clinical and epidemiological characteristics appear to change around those ages. In some documents, ‘infantile’ asthma (<2 or 3 years) is further distinguished. Special characteristics of adolescence are emphasized in most documents (Figure 1A).

There is slightly less consistency when it comes to severity and persistence, which have been extensively used in the past to classify asthma. In respect to persistence, asthma is usually classified as intermittent or persistent; in addition, infrequent and frequent intermittent classes are proposed by the AAMH. With respect to severity, persistent asthma is usually classified in mild, moderate and severe. However, in PRACTALL and SIGN, only severe asthma is mentioned, while in the JGCA, a ‘most severe’ class is proposed. Classifications of severity/persistence are challenging as they require differentiation between the inherent severity of the disease, resistance to treatment and other factors, such as adherence to treatment. Hence, these classifications are currently recommended only for initial assessment of the disease severity and are being replaced by the concept of ‘control’, which is more clinically useful.

Control is generally accepted as a dynamic classification factor, critical to guiding treatment. Control categories are quite relevant in clinical practice. Slightly different terms are used for levels of asthma control, which are generally three (controlled, partly controlled, and uncontrolled). In some cases ‘complete’ control is described, as a state with no disease activity (Table 1).

Table 1. Asthma Control.

Components of asthma control include current impairment (symptoms, need for rescue medication, limitation of activities, lung function in children >5 years) and future risk (exacerbations, medication side effects). Levels of control are indicative; the most severe impairment or risk, defines the level.

| Domain | Component | Level of Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Good | Partial | None | ||

| Impairment | Symptoms – Daytime | None | ≤2/week | >2/week | Continuous |

| Symptoms – Night- time/awakenings |

None | ≤1/month | >1/month | Weekly | |

| Need for rescue medication | None | ≤2/week | >2/week | Daily | |

| Limitation of activities | None | None | Some | Extreme | |

| Lung function - FEV1, PEF (predicted or personal best) |

>80% | ≥80% | 60%-80% | <60% | |

| Risk | Exacerbations (per year) | 0 | 1 | 2 | >2 |

| Medication side effects | None | Variable | |||

In assessing severity and control, a distinction of current impairment and future risk is proposed by NAEPP and GINA. Although not stated in the other documents, these two elements are clearly distinguishable and may differentially respond to treatment, therefore they should be considered independently.

Subgrouping into phenotypes is frequently mentioned: GINA and GINA<5 refer to different phenotype classification systems, commenting that their clinical usefulness remains a subject of investigation. NAEPP suggests that evidence is emerging for phenotypic differences that may influence treatment choices, but does not propose a specific classification system. PRACTALL proposes a phenotype classification according to apparent trigger (virus-induced, exercise-induced, allergen-induced, and unresolved), suggesting that these should be taken into account for treatment selection. The above variation may reflect the rapidly developing evidence with respect to different subgroups of pediatric asthma. For many patients several apparent triggers may be identified, also varying over time, highlighting the difficulty to provide a simple phenotype classification system. Future phenotypic classifications should demonstrate important advantages in management. Notably most documents give special consideration to ‘exercise-induced asthma’, and ‘severe asthma’.

Research Recommendations:

|

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

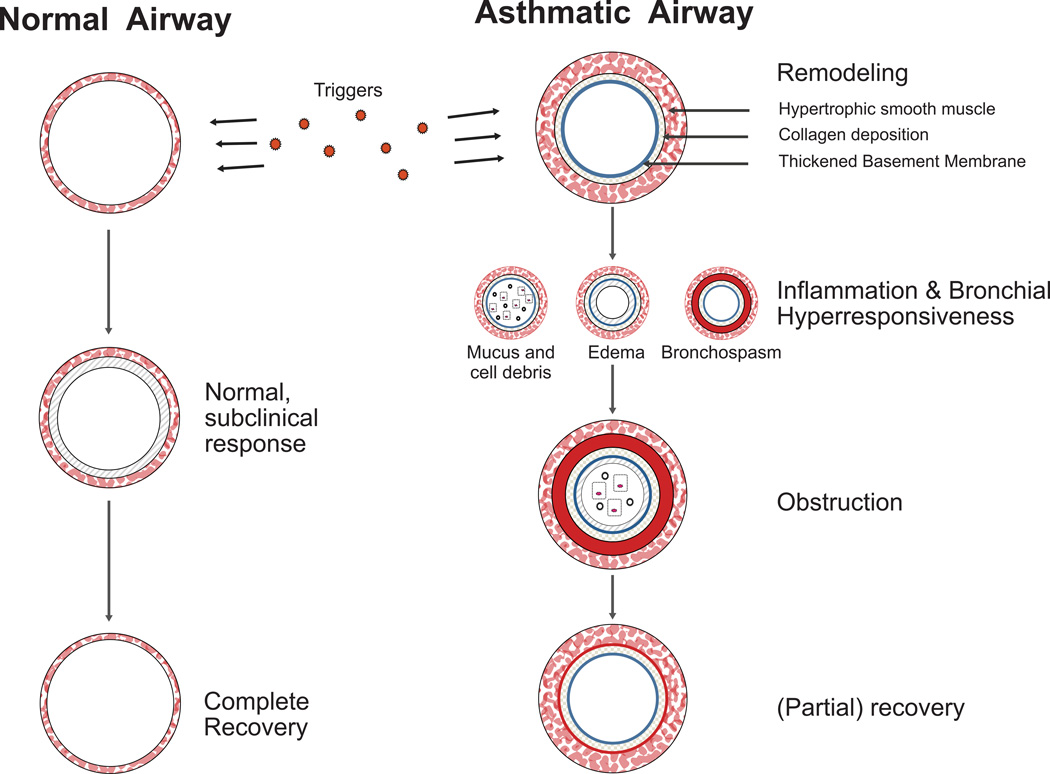

There is general agreement that asthma is a disease of chronic inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness and chronic structural changes known as airway remodeling (Figure 2). Some of the guidelines provide extensive discussion of these topics, while others focus mostly on diagnosis and treatment and mention these concepts in introductory remarks or as part of an asthma definition.

Asthma can begin at any age but most often has its roots in early childhood (11). The prevalence of asthma has increased in many countries (12), although in some cases it may have leveled off (12, 13). Since asthma inception depends on both genetics (14, 15) and the environment (16), modifiable environmental factors have been sought in an effort to identify targets for prevention. Many guidelines mention infections, exposure to microbes, stress, pollutants, allergens and tobacco smoke as possible contributing factors. The development of allergen-specific IgE, especially if it occurs in early life, is an important risk factor for asthma, especially in developed countries (17).

Unfortunately, to date this knowledge has not translated into successful programs for primary prevention. Although increased exposure to mainly indoor allergens has been implicated in the development of asthma through induction of allergic sensitization (17, 18), current guidelines avoid giving specific recommendations, as the few existing intervention studies have produced conflicting results (19–21). Avoidance of exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy and infancy is the only properly documented modifiable environmental factor that can be safely recommended for the primary prevention of asthma (Evidence B). Other, potentially useful, interventions, such as maternal diet (22) or vitamin D supplementation (23), require confirmation, whereas agents that would mobilize regulatory immune mechanisms for the primary prevention of asthma (eg. oral bacterial products, immunomodulators) are being actively pursued (24).

Persistent asthma is universally regarded as a disease of chronic airway inflammation. Increased populations of mast cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and others contribute to inflammation (25, 26). Structural cells such as epithelial cells and smooth muscle cells may also contribute to the inflammatory milieu (27, 28). The inflammatory and structural cells collectively produce mediators such as cytokines, chemokines and cysteinyl leukotrienes that intensify the inflammatory response and promote airway narrowing and hyperresponsiveness (29). AHR is associated with excessive smooth muscle contraction in response to non-specific irritants, viral infections, and for allergic individuals, exposure to specific allergens (30, 31). Neural mechanisms, likely initiated by inflammation, contribute to AHR (32).

Acute episodes of airway narrowing are initiated by a combination of edema, infiltration by inflammatory cells, mucus hypersecretion, smooth muscle contraction, and epithelial desquamation. These changes are largely reversible; however, with disease progression airway narrowing may become progressive and constant (33). Structural changes associated with airway remodeling include increased smooth muscle, hyperemia with increased vascularity of subepithelial tissue, thickening of basement membrane and subepithelial deposition of various structural proteins, and loss of normal distensibility of the airway (34, 35). Remodeling, initially described in detail in adult asthma, appears to be also present in at least the more severe part of the spectrum in pediatric asthma (36, 37).

Research Recommendations:

|

Natural History

Asthma may persist or remit and relapse (38). Natural history and prognosis are particularly important in children, since a considerable proportion of children who wheeze outgrow their symptoms at some age (39). The likelihood of long-term remission, on one hand, or progression and persistence of disease, on the other, has received considerable attention in the medical literature over the last decade (40–42). However, the natural history of asthma, with the exception of the common understanding that asthma starts early in life and may run a chronic course, is not prominent in many current guidelines.

The most detailed reference to natural history is made in the NAEPP. Among children who wheeze before the age of 3 years, the majority will not experience significant symptoms after the age of 6 years. Nevertheless, it appears that decrements in lung function occur by the age of 6 years, predominantly in those children whose asthma symptoms started before 3 years of age. The Asthma Predictive Index (API) uses parental history of asthma and physician diagnosis of atopic dermatitis as major criteria, along with peripheral blood eosinophilia, wheezing apart from colds and physician diagnosis of allergic rhinitis as minor criteria, to predict disease persistence at the age of 6 years, in children younger than 3 years with a history of intermittent wheezing (43). As shown in at least 3 independent populations (43–45), the API holds a modest ability to predict disease persistence into early school-age and is also recommended by GINA<5 (Evidence C). However, extrapolation of findings from epidemiological studies to the assessment of future risk in individual patients in the clinical setting, or in different populations, may not be as straightforward (46).

PRACTALL also stresses the variable natural history patterns of recurrent wheezing in early childhood. Infants with recurrent wheezing have a higher risk of developing persistent asthma by the time they reach adolescence, and atopic children in particular are more likely to continue wheezing. In addition, the severity of asthma symptoms during the first years of life is strongly related to later prognosis. However, both the incidence and period prevalence of wheezing decrease significantly with increasing age.

Research Recommendations:

|

Diagnosis

History of recurrent episodes of wheezing is universally accepted as the starting point for asthma diagnosis in children. The required number/rate of such episodes is generally not specified, although an arbitrary number of 3 or more has been proposed. Typical symptom patterns are important for the establishment of the diagnosis. These include recurrent episodes of cough, wheeze, difficulty in breathing or chest tightness, triggered by exposure to various stimuli such as irritants (cold, tobacco smoke), allergens (pets, pollens, etc.), respiratory infections, exercise, crying or laughter, appearing especially during the night or early morning (Evidence A–B). Personal history of atopy (e.g. eczema, allergic rhinitis, or food/aeroallergen sensitization) and family history of asthma strengthen the diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2. Diagnosis of Pediatric Asthma.

To diagnose asthma, confirm the presence of episodic symptoms of reversible airflow obstruction, and exclude other conditions (Table 3). Diagnosis components are listed below in (relative) sequence of importance

| ➢ History |

| ✓ Recurrent respiratory symptoms (wheeze, cough, dyspnea, chest tightness) |

| ▪ typically worse at night/early morning |

| ▪ exacerbated by exercise, viral infection, smoke, dust, pets, mold, dampness, weather changes, laughing, crying, allergens |

| ✓ Personal history of atopy (eczema, food allergy, allergic rhinitis) |

| ✓ Family history of asthma or atopic diseases |

| ➢ Physical examination |

| ✓ Chest auscultation for wheezing |

| ✓ Symptoms/signs of other atopic diseases such as rhinitis or eczema |

| ➢ Evaluation of lung function (spirometry with reversibility testing, preferred to PEFR, which can nevertheless be used if resources are limited) |

| ➢ Evaluation of atopy (skin prick tests or serum specific IgE) |

| ➢ Studies for exclusion of alternative diagnoses (e.g. chest X-ray) |

| ➢ Therapeutic trial |

| ➢ Evaluation of airway inflammation (FeNO, sputum eosinophils) |

| ➢ Evaluation of bronchial hyperresponsiveness (non-specific bronchial challenges e.g. methacholine, exercise) |

Taking into account that asthma symptoms are not pathognomonic and may occur as a result of several different conditions, differential diagnosis is very important and includes common childhood problems as well as a long list of mostly infrequent but rather severe diseases, which are listed with minor differences in all guidelines (Table 3).

Table 3. Pediatric Asthma Differential Diagnosis.

| Infectious & Immunological disorders |

| Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis |

| Anaphylaxis |

| Bronchiolitis |

| Immune deficiency |

| Recurrent respiratory tract infections |

| Rhinitis |

| Sinusitis |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Tuberculosis |

| Bronchial pathologies |

| Bronchiectasis |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| Cystic fibrosis |

| Primary ciliary dyskinesia |

| Mechanical obstruction |

| Congenital malformations |

| Enlarged lymph nodes or tumor |

| Foreign body aspiration |

| Laryngomalacia/Tracheomalacia |

| Vascular rings or laryngeal webs |

| Vocal cord dysfunction |

| Other systems |

| Congenital heart disease |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| Neuromuscular disorder (leading to aspiration) |

| Psychogenic cough |

Evaluation of lung function

Evaluation of lung function is important for both diagnosis and monitoring. Nevertheless, normal lung function tests do not exclude a diagnosis of asthma, especially for intermittent or mild cases (47). Therefore these tests are considered supportive. Performing the tests when the child is symptomatic may increase sensitivity.

Spirometry is recommended for children old enough to perform it properly; the proposed range of minimum age is between 5 and 7 years. At this time, given the sparse evidence available, decision points do not differ from those used in adults (FEV1: 80% of predicted, reversible after bronchodilation by ≥12%, 200ml, or ≥10% of predicted), however these should be re-evaluated. Spirometry may not be readily available in some settings, particularly low income countries.

Peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurements, including reversibility or variability, may also help support a suspected diagnosis, in children capable of performing them properly. However, NAEPP points out that a normal range for PEF is wide and so it is more useful for monitoring rather than diagnosis.

In children younger than 5 years, newer lung function tests that require less cooperation have been used (such as oscillometry (48) or specific airway resistance (49)), however these are not generally available outside specialized centres.

Evaluation of AHR and airway inflammation

Airway hyperresponsiveness, assessed by provocation with inhaled methacholine, histamine, mannitol, hypertonic saline or cold air, has been used in adults to either support or rule out the diagnosis of asthma. The use of these methods in children is supported with reservation by most asthma guidelines. However, accuracy in children is lacking, as the inhaled dose is not adjusted for the size of the patient. Exercise can also be used to assess AHR, but standardization of testing is difficult for children of differing ages (50). These methodological issues have contributed to the tests being mainly limited to use in research rather than clinical practice (51, 52).

Although the guidelines do not stress the utility of obtaining fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) measurements, recent data support that it may be useful as a diagnostic tool. An evidence-based guideline for the use and interpretation of FENO has been recently published (53). It supports the use of FENO to detect eosinophilic airway inflammation, determining the likelihood of corticosteroid responsiveness, monitoring of airway inflammation to determine the potential need for corticosteroid, and unmasking of non-adherence to corticosteroid therapy. However, in many countries, the capacity to measure FENO is unlikely to be available outside specialized centres.

Sputum eosinophils, although promising, have not been supported by data robust enough to make this parameter clinically useful and therefore are not currently recommended for diagnosis or monitoring of childhood asthma.

Evaluation of atopy

There is general consensus that atopy should be evaluated in children when there is a suspicion or diagnosis of asthma. Identification of specific allergic sensitizations can support asthma diagnosis, indicate avoidable disease triggers and has prognostic value for disease persistence (52, 54). Both in vivo (skin prick tests) and in vitro (specific IgE antibodies) methods can be used, considering ease of performance, cost, accuracy and other parameters.

Special considerations

There are important differences in the approach to diagnosis according to age. Most guidelines recognize the difficulty in diagnosing asthma in children younger than 2–3 years. In addition to the lack of objective measures at that age, the suboptimal response to medications and variability of natural history makes diagnosis in this age group, at best, provisional (55, 56).

In cases of uncertainty in the diagnosis, particularly in children below the age of 5 years, a short therapeutic trial period (e.g. three months) with inhaled corticosteroids is suggested. Considerable improvement during the trial and deterioration when it is stopped supports a diagnosis of asthma, although a negative response still does not completely exclude the diagnosis (Evidence D).

Although the diversity of childhood asthma is generally recognized and various phenotypes or subgroups are mentioned in different documents, there is little detail or agreement on diagnostic requirements for particular phenotypes, with the exception of exercise-induced asthma.

Research Recommendations:

|

Principles of Pediatric Asthma Management

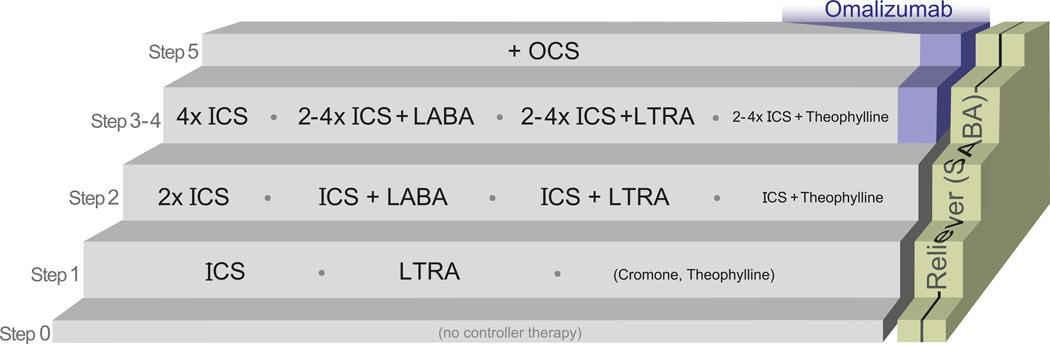

Although there is considerable variation in the way that different guidelines structure and present the principles and components of asthma management, the key messages are consistent, including a number of components that are a consequence of its chronic and variable course (Figure 3).

Patients and their parents or caregivers should be educated to optimally manage the disease, in collaboration with health care professionals. Education and the formation of a partnership between them are crucial for the implementation and success of the treatment plan (Evidence A–B).

Identification (Evidence A) and avoidance (Evidence B–C) of specific (i.e. allergens) and non-specific triggers (e.g. tobacco smoke, but not exercise) and risk factors are also of significant importance, since these may drive or augment inflammation.

Assessment and monitoring should be performed regularly because of the variable course of asthma and importantly to re-evaluate and fine-tune treatment (Evidence A–B).

Pharmacotherapy is the cornerstone of treatment. The optimal use of medication can, in most cases, help patients control their symptoms and reduce the risk for future morbidity.

Allergen specific immunotherapy should be considered for children whose symptoms are clearly linked to a relevant allergen (Evidence B).

The management of asthma exacerbations is a major consideration, independent from chronic treatment.

There is a trend towards considering phenotype-specific treatment choices, however there is as yet no consistent approach to this. Exercise-induced asthma is recognized in all guidelines and specific instructions are suggested for its management. In addition, the specific challenges of treating severe and difficult asthma are highlighted throughout the documents. Age-specific instructions are usually proposed in 2 or 3 strata. It is generally accepted that recommendations in the youngest age group are based on very weak evidence.

Overall, the treatment goal is disease control, including reduction of future risk of morbidity such as exacerbations. In the past there were suggestions that early treatment may be able to alter the natural course of the disease, however, a number of recent studies (57–59) have shown that even prolonged treatment with inhaled corticosteroids, despite its many benefits (60), is unable to do so (Evidence A). Allergen specific immunotherapy is currently the only treatment with long-term disease-modifying potential (61–63), however, the evaluation of the evidence base for this effect is controversial among experts, and therefore needs further studies.

Research Recommendations:

|

Education

Asthma education should not be regarded as a single event but rather as a continuous process, repeated and supplemented at every subsequent consultation. There is general consensus on the basic elements of asthma education: it should include essential information about the (chronic/relapsing) nature of disease, the need for long-term therapy, and the different types of medication (‘controllers’ and ‘relievers’). Importantly, education should highlight the importance of adherence to prescribed medication even in the absence of symptoms, and should involve literal explanation and physical demonstration of the optimal use of inhaler devices and peak flow meters. Education should be tailored according to the socio-cultural background of the family (64).

Education for self-management is an integral part of the process (Evidence A); it does not intend to replace expert medical care, but to enable the patient and/or the caregiver to help reach and maintain control of asthma, forming a functional partnership with the health care professional in dealing with daily aspects of the disease. This involves ability to avoid or manage identifiable triggers, such as infections, allergens and other environmental factors (e.g. tobacco smoke).

The use of a written, personalized management plan is generally recommended (Evidence B); the term ‘asthma action plan’ is most commonly used. This should optimally include the daily medication regimen, as well as specific instructions for early identification and appropriate management of asthma exacerbations or loss of asthma control. Educated interpretation of symptoms is of primary importance, as well as the use of PEF monitoring values as a surrogate measure of current asthmatic status (Evidence A), although this may be challenging in younger children. Supplemental material and/or links to information resources for structured templates and further guidance are available in several documents (AAMH, GINA, NAEPP, and SIGN). Unfortunately, the uptake of written action plans is poor, both by patients and by practitioners.

It is generally recognized that different approaches should be sought for different age groups; in particular, JGCA and PRACTALL recommend an age-specific stratification of educational targets, with incremental participation of older children in self-management programs.

Most educational interventions have been shown to be of added value (and thus should be intensely pursued) mainly in patients with moderate or severe asthma; milder cases may benefit as well but clinical effect is more difficult to formally demonstrate.

Primary asthma education in the office/clinic may be complemented by educational interventions at other sites. School-based programs (65), often peer-led in the case of adolescents, may have increased penetration and acceptance in large numbers of asthmatic children (Evidence B). Patients and their families may also be provided brief, focused educational courses when being admitted to hospital emergency departments for asthma exacerbations, while use of computer- and internet-based educational methods represent other proposed alternatives, especially for older children and adolescents (Evidence B).

Focused training in pharmacies and education of the general public receive relatively less priority by current guidelines. Finally, education of health authorities and politicians is only mentioned by PRACTALL. Education of health care professionals is self-evident.

Research Recommendations:

|

Trigger avoidance

Asthma symptoms and exacerbations are triggered by a variety of specific and non-specific stimuli. It is reasonable that avoidance of these factors may have beneficial effects on the activity of the disease. The airway pathophysiology mediated through IgE to inhalant allergens is widely acknowledged; however, not every allergen is equally significant for all patients. Thus, there is general consensus that sound allergological workup (including careful history for assessment of clinical relevance, skin prick testing and/or specific IgE measurement) should precede any effort to reduce exposure to the corresponding allergen (Evidence B).

There is some ambiguity with respect to the role of allergen avoidance. Some documents (JGCA, NAEPP3 and PRACTALL) provide specific recommendations for reduction of allergen exposure for sensitized patients with asthma. Indoor allergens (dust mite, pet, cockroach and mold allergens) are considered the main culprits and are targeted by specific interventions (Evidence B–D, depending on allergen and intervention). Other guidelines (AAMH, GINA, and SIGN) are more cautious in the interpretation of the evidence and underline the unproven effectiveness of current avoidance strategies on asthma control. Complete allergen avoidance is usually impractical, or impossible, and often limiting to the patient, and some measures involve significant expense and inconvenience. Moreover, the prevailing view is that single interventions for indoor allergens have limited effectiveness; if measures are to be taken, a multifaceted, comprehensive approach is prerequisite for clinical benefit (Evidence A), while tailoring environmental interventions to specific sensitization profiles has been shown to be of added value (66). Outdoor allergens are generally less manageable, since their levels cannot be modified by human intervention and staying indoors for appropriate periods may be the only recommendable approach.

Indoor and outdoor pollution can be major triggers particularly in developing countries (67). It is clear that smoking cessation in adolescents and reduction of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, as well as to various indoor and outdoor pollutants and irritants should be attempted in children with asthma (Evidence C). Vigorous measures are needed to achieve avoidance. Likewise, in the relatively uncommon case of drug-sensitive (e.g. NSAIDs) or food-sensitive (e.g. sulphites) children with asthma, complete avoidance should be advised, but only after thoroughly assessing the causality.

Research Recommendations:

|

Pharmacotherapy

The goal of asthma treatment is control using the least possible medications. Asthma pharmacotherapy is regarded as chronic treatment and should be distinguished from treatment of acute exacerbations that is discussed separately.

In the initial assessment, and especially if the patient has not received asthma medication before, there is a unique opportunity to evaluate disease severity. Most guidelines propose the use of severity as the criterion for selecting the level of treatment at the first assessment. GINA omits this step in this edition, while PRACTALL suggests that both severity and control can be used.

After the initial assessment, pharmacological therapy is selected through a step-wise approach according to the level of disease control. In evaluating control, the differentiation between current impairment and future risk is considered in NAEPP and GINA. This additional consideration is important in appreciating the independence of these elements.

If control is not achieved after 1–3 months, stepping up should be considered, after reviewing device use, compliance, environmental control, treatment of co-morbid rhinitis and, possibly, the diagnosis. When control has been achieved for at least 3 months, stepping down can be considered (Evidence A–B).

Drug classes and their characteristics

Despite the progress in asthma research, current asthma medications belong to a small range of pharmacological families. Corticosteroids, beta-2 adrenergic agonists and leukotriene modifiers are the predominant classes. Chromones and xanthines have been extensively used in the past but are now less popular, the former because of limited efficacy and the latter because of frequent side-effects. Omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IgE, is the newest addition to asthma medications, the first from the family of immunomodulatory biological agents, of which several other molecules are currently under evaluation in clinical trials. Medications are classified, according to their use, in those used for acute relief and those used for long-term control.

Medications used for acute relief of symptoms

‘Relievers’ are used for the acute, within minutes, relief of asthma symptoms, through bronchodilation. Use of inhaled short-acting beta-2 adrenergic agonists (SABA), most commonly salbutamol, as first line reliever therapy is unanimously promoted for children of all ages (Evidence A). They are typically given on an ‘as needed’ basis, though frequent or prolonged use may indicate the need to initiate or increase anti-inflammatory medication. Compared to other relievers, SABA have a quicker and greater effect on airway smooth muscle, while their safety profile is favorable; a dose-dependent, self-limiting tremor and tachycardia are the most common side-effects.

Oral SABA are generally discouraged. Anticholinergic agents, mainly ipratropium, are second-line relievers, but are less effective than SABA.

Medications used for long-term asthma control

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)

The use of ICS as daily controller medications in persistent asthma is ubiquitously supported, as there is robust evidence that therapeutic doses of ICS improve symptoms and lung function, decrease need for additional medication and reduce rate of asthma exacerbations and asthma-induced hospital admissions in children of all ages (68). Due to their pleiotropic anti-inflammatory activity, initiation of ICS therapy generally constitutes the first step of regular treatment (Evidence A).

Most children with mild asthma can be well-controlled with low-dose ICS (Table 4). Though dose-response curves have not been established for every ICS formulation and for all age groups, efficacy appears to reach a plateau for most patients and outcomes around or below medium-dose range (69, 70). It should be noted, however, that the evidence on the role of low-dose ICS as maintenance treatment for prevention of intermittent, virus-induced wheezing in young children, is limited and controversial (71).

Table 4. Inhaled Steroid (ICS) dose equivalence.

Inhaled steroids and their entry (low) doses. Medium doses are always double (2x), while high doses are quadruple (4x), with the exception of flunisolide and triamcinolone which are 3x.

| Drug | Low daily dose (µg) |

|---|---|

| Beclomethasone dipropionate HFA | 100 |

| Budesonide | 100 |

| Budesonide (nebulized) | 250 |

| Ciclesonide | 80 |

| Flunisolide | 500 |

| Flunisolide HFA | 160 |

| Fluticasone propionate HFA | 100 |

| Mometasone furoate | 100 |

| Triamcinolone acetonide | 400 |

After control has been achieved, patients should be gradually titrated down to the lowest effective dose. The clinical response may vary among patients; therefore the optimal maintenance dose is sought on an individual basis.

The clinical benefit of ICS must be balanced against potential risks, with linear growth remaining the dominant concern. Several studies in older children have consistently demonstrated a modest but significant effect (~1cm in the first year) (59, 72, 73), while studies in preschool-age children are less consistent. The effect appears to improve with time, however, there are concerns about subgroups who may be more susceptible or permanently affected (59, 74). Recent data from the CAMP study suggest that an effect on adult final height cannot be excluded (75).

Risks for subcapsular cataracts or bone mineral density reduction in childhood are very low.

Most of the information available refers to low to medium doses and there is minimal information on high dose ICS. Furthermore, the total steroid load in cases of concomitant use of local steroids for allergic rhinitis or eczema should be taken into account.

Inhaled steroids differ in potency and bioavailability; however, because of both a relatively flat dose-response relationship in asthma, and considerable interpersonal variability, few studies have been able to confirm the clinical relevance of these differences.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA)

Among leukotriene modifiers, montelukast is available worldwide; zafirlukast is mentioned only in NAEPP and pranlukast only in JGPA. LTRA are effective in improving symptoms and lung function and preventing exacerbations at all ages (76, 77) (Evidence A). They are generally less efficacious than ICS in clinical trials, although in some cases non-inferiority has been shown (78, 79). Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting particular effectiveness of montelukast in exercise-induced asthma, possibly superior to other treatments (80). Therefore, in most guidelines they are recommended as second choice after low dose ICS, or occasionally as ‘alternative first line treatment’ (AAMH, PRACTALL), for the initial step of chronic treatment. In the context of the next treatment steps, they are also effective as add-on medications, but less so in comparison to LABA (81). PRACTALL also suggests that LTRA may be particularly useful when the patient has concomitant rhinitis.

Montelukast is relatively free of adverse effects. With zafirlukast signs of hepatic dysfunction should be monitored.

Long-acting beta-2 adrenergic agonists (LABA)

LABA, including salmeterol and formoterol, have long lasting bronchodilator action. In older children and adults, ICS-LABA combinations have been shown to improve asthma outcomes to a better extent than higher doses of ICS (82–84). However, a small, but statistically significant risk for severe exacerbations and death associated with daily use of LABA has been described (85–87). Furthermore, the evidence base of the efficacy of ICS-LABA combinations in young children is not as robust as that of older children and adults (88, 89). These concerns are probably behind the rather controversial position of LABA in pediatric asthma treatment.

All documents agree that LABA should only be prescribed in combination with ICS, and are therefore relevant as add-on treatment. In some cases, ICS-LABA combinations are recommended as the preferred add-on treatment in children >5 years (SIGN, GINA), or >12 years (NAEPP), in other they are suggested as an option for children >5 years (AAMH, NAEPP) or at any age (JGPA), while in other as an add-on treatment at a subsequent step (PRACTALL); GINA<5 does not recommend them for children < 5 years due to lack of data.

In the absence of data of safety and efficacy in children younger than 5 years, it is probably better to be cautious, until such data are produced. For older children, it is clear that ICS+LABA are an important treatment option, preferable for at least a subpopulation of patients (90). It is important to appreciate the right balance between risk and benefits of therapy (91, 92).

The use of a single combination inhaler, rather than separate inhalers, is generally recommended, to maximize adherence and efficacy and reduce the possibility of overuse of LABA and underuse of ICS with potential for serious side effects.

Taking advantage of the fast action of formoterol, a strategy proposing the use of a single inhaler for both reliever and controller medication (SMART strategy) has been evaluated in several trials, mostly in adults. The efficacy has also being shown in children (87, 93).

Cromones

Cromolyn sodium and nedocromil modulate mast cell mediator release and eosinophil recruitment. Several studies have shown some effectiveness in children >5 years, however, evidence is not robust (94, 95). They are administered 3–4 times a day and are certainly less effective than ICS. On the other hand, they have an excellent safety profile. Based on these, cromones are considered having a limited role, but are ‘traditionally’ included in most guidelines as second-line medications for mild disease/initial treatment steps and prevention of exercise-induced asthma. In any case, they are not available anymore in many countries.

Theophylline

Theophylline, the most used methylxanthine, has bronchodilatory properties and a mild anti-inflammatory action. It may be beneficial as add-on to ICS, however less so than LABA (Evidence B). However, it has a narrow therapeutic index and can have serious side effects, therefore requiring monitoring of blood levels (96). As a result, its role as controller medication is very limited and is only recommended as second line treatment, where other options are unavailable (96).

Omalizumab

Omalizumab is indicated for children with allergic asthma poorly controlled by other medications (Evidence B). It reduces symptoms and exacerbations, and improves quality of life and to a lesser extent lung function (97–100).

Strategies for asthma pharmacotherapy

Detailed strategies for prescribing asthma medications are proposed in all guidelines. Although there are differences on structure and detail between the documents, several common elements can be identified. Age is always taken into account. In infants, the evidence base for treatment is small and responses are inconsistent and frequently suboptimal. In adolescents, issues that may affect asthma management are mostly related to lack of compliance.

There is consensus that medication for acute relief of symptoms (typically, a short acting inhaled beta-2 agonist) should be available to all asthma patients, irrespective of age, severity or control. The reliever is used as needed; frequent or increased use may indicate lack of control and the need to initiate/step up controller therapy.

A number of steps of controller therapy can be described:

Step 0: In the lowest step, no controller medication is proposed.

Step 1: The next step entails the use of one controller medication. An ICS at low dose is the preferred option in most cases (Evidence A). LTRAs are recommended as second option (GINA, GINA<5, NAEPP, SIGN <5 years), only if steroids cannot be used (SIGN 5–12 years), equivalent (PRACTALL, AAMH), or even preferred option (JGCA <5 years). Possible explanations for these variations are that generally ICS are more effective than LTRA in direct comparisons (101, 102), although there are patients that may respond better to LTRA, especially in the younger and less atopic children (103). LTRA have a favorable safety profile and ease of administration and acceptance by the parents and patients (104). Cromones (NAEPP, AAMH, JGCA, SIGN) and theophylline (in children >5 years, NAEPP, JGCA, SIGN) are also included as options at this step. However, cromones are not available anymore in many countries, while, for the reasons mentioned above, theophylline should probably be excluded from this step, with the exception of developing countries where first line medication may be unavailable or unaffordable.

-

Step 2: ICS can be increased to a medium dose, or a second medication can be added. This is probably the most variable and to some extent controversial step. For children older than 5 years, GINA and SIGN recommend the combination of ICS+LABA, the JGCA and AAMH documents prefer increasing the ICS dose, NAEPP has no preference for children 5–12 years, but recommends either doubling ICS or ICS+LABA for children >12 years, while PRACTALL suggests either doubling ICS or ICS+LTRA. For children younger than 5 years, increasing ICS is the commonest approach (GINA<5, AAMH, JGCA, and NAEPP); SIGN suggests ICS + LTRA, while PRACTALL suggests either doubling ICS or ICS+LTRA.

Nonetheless, the above variation refers to preferred choices among lists of options that are similar among the documents. In respect to the younger age group, the small number of studies explains this discrepancy. In older children, choices of safety versus efficacy may influence the recommendations. However, there is good evidence suggesting that the response to medication may differ considerably among individuals (90, 103), suggesting the need for some flexibility in choice and an option to try a different strategy if the first is not successful.

Step 3–4: The subsequent step(s) represent the maximization of conventional treatment, with the use of additional medications and/or further increase of the ICS dose. This may include two distinct steps: in the first, LABA or LTRA (or exceptionally theophylline) is added to the medium dose ICS and in the second the ICS dose is increased (NAEPP, AAMH). Omalizumab is also considered at this step by NAEPP.

Step 5: In cases where control cannot be achieved with the maximum dose of inhaled corticosteroids and additional medication, the final resort is the use of oral corticosteroids. This step is not always part of the algorithm (JGCA, AAMH, SIGN <5 years), possibly because at this stage specialist consultation is warranted. GINA includes omalizumab here.

All guidelines recommend that asthma education, avoidance of triggers, evaluation of compliance and correct use of inhaler device, and even reconsideration of the diagnosis, should be done before stepping up treatment, in children in whom control is difficult to achieve. In addition, concomitant diseases, such as allergic rhinitis, should always be taken into account (105).

Based on the above, a simplified algorithm is shown in Figure 4.

It should be noted that in low income countries, an important obstacle to asthma management is the cost of medications. Essential asthma drugs (SABA and ICS) are proposed by The Union Asthma Guidelines (106).

Delivery devices

In addition to the selection of medication, understanding and selection of the optimal device for inhaled drug delivery is an important consideration. Devices fall under 3 categories: pressurized meter-dose inhalers (pMDI), dry powder inhalers (DPI) and nebulizers. Breath-actuated MDIs have distinct characteristics. There is no robust evidence suggesting major differences in effectiveness between the device types, however each type has specific merits and limitations (107). There is general consensus that prescription of a device should be individualized, with major criteria being the patient’s ability to use, preference and cost. A detailed review of different devices has been recently published (108). Training is vital (109). pMDI and DPI are preferred to nebulizers, as they are at least equally effective (110, 111), cheaper and easier to use and maintain. Spacers should always be used with MDIs in 0–5 year-olds and in exacerbations; they are also preferable in older children. Care needs to be taken to minimize static charge in plastic spacers (112). A mouthpiece should substitute for the mask when the child is able to use it. In areas where commercially produced spacers are unavailable or unaffordable, a 500ml plastic bottle spacer may be adapted to serve as an effective spacer for children of all ages (113). The effects of anatomical differences and low inspiratory flows of young children on medication deposition by different drug delivery devices and spacers, are not well understood.

Taking the above into account, a simplified selection scheme is shown in Box 2.

Box 2 – Inhaled medication delivery devices.

0 – ~5 years

pMDI with static-treated spacer and mask (or mouthpiece as soon as the child is capable of using)

> ~5 years

Choice of: pMDI with static-treated spacer and mouthpiece, DPI (rinse or gargle after inhaling ICS), breath actuated pMDI (depending on patient ability to use, preference)

Nebulizer: second choice at any age

Research Recommendations:

|

Immunotherapy

Allergen specific immunotherapy (SIT) involves the administration of increasing doses of allergen extracts to induce persistent clinical tolerance in patients with allergen-induced symptoms. Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) has been shown to be clinically effective in allergic asthma, leading to a significant reduction in symptoms, airway hyper-responsiveness and medication requirements (Evidence A–B). These effects are generally considered to be greatest when standardized, single-allergen extracts of house dust mites, animal dander, grass or tree pollen are administered, whereas definitive evidence is currently lacking for the use of multi-allergen extracts and for mold and cockroach allergens (114, 115).

In clinical practice, allergen is typically administered for 3 to 5 years. A specific age limit, above which SIT can be initiated has not been clearly defined; PRACTALL suggests it may represent an acceptable intervention above 3 years of age, while GINA<5y, suggests that no recommendation can be made at this age, due to scarce evidence.

SIT has some important advantages over conventional pharmacological treatment (116); first, it is the closest approach to a causal therapy in allergic asthma; second, its clinical effect has been shown to persist after discontinuation of treatment (61, 62); and third, SIT has been linked with a preventive role against the progression of allergic rhinitis to asthma and the development of sensitization to additional allergens (63, 117). However, several experts feel that these aspects of SIT have not been adequately demonstrated.

Nevertheless, convenience and safety of administration have been a matter of concern. Apart from common local side effects at the injection site, systemic reactions (including severe bronchoconstriction) may occasionally occur, and these are more frequent among patients with poor asthma control (118). It is therefore generally agreed that SIT should only be administered by clinicians experienced in its use and appropriately trained to identify and treat potential anaphylactic reactions. Furthermore, SIT is not recommended in severe asthma, because of the concern of possible greater risk for systemic reactions.

Clinical benefits of SIT are differentially weighed against safety issues, so some recommendations vary between guidelines. AAMH, SIGN and NAEPP acknowledge a clear role for immunotherapy as an adjunctive treatment, provided that clinical significance of the selected allergen has been demonstrated. PRACTALL also endorses immunotherapy and further suggests SIT to be considered as a potential preventive measure for the development of asthma in children with allergic rhinitis. According to GINA, the option of immunotherapy should only be considered when all other interventions, environmental and pharmacologic, have failed. However, in such unresponsive condition, the efficacy of immunotherapy is neither warranted.

In the context of ICON, the discussion on the role of SIT in childhood asthma has also been controversial. It is clear that additional studies are needed in order to be able to provide clear recommendations in the future.

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) is painless and child-friendly in terms of administration route, offering the desirable option of home dosing and a more favorable safety profile compared to SCIT. Most documents require additional evidence of efficacy before recommending SLIT as a valid therapeutic option in asthma management. Nevertheless, a relevant metaanalysis confirmed significant efficacy in children with asthma (119).

Research Recommendations:

|

Monitoring

When asthma diagnosis has been confirmed and treatment initiated, ongoing monitoring of asthma control is strongly recommended (Evidence B–C). Control can be assessed at regular intervals, based on the components described in Table 1. Generally, only minimal symptoms are acceptable. For patients on daily controller therapy, reviews approximately every 3 months are suggested; after an exacerbation a shorter interval should be considered (Evidence D). Several validated tools for assessing asthma control in children have been published (120–124).

Spirometry is recommended as a valuable measure for monitoring lung function in children who can perform it (Evidence B). Peak expiratory flow monitoring is recommended as an option for assessing control and home monitoring of more severe patients, or those with poor perception of severity (Evidence B).

Monitoring adherence to asthma therapy and assessment of inhaler technique are important (109, 125, 126). Self-monitoring at home (e.g. symptoms, PEF), as part of a personal management plan is encouraged.

Additional recommendations, not uniformly suggested, include monitoring of quality of life (AAMH, NAEPP, SIGN) (Evidence C), and of adverse effects of asthma therapy, particularly growth rate (AAMH, NAEPP, PRACTALL, SIGN). Multiple monitoring methods may be useful in some cases.

Monitoring FENO is not recommended by the referenced pediatric asthma guidelines; however, it has been recently favorably reevaluated (94, 127). In contrast, the role of monitoring bronchial hyperresponsiveness or induced sputum eosinophilia is not currently well established (128–131).

Monitoring should continue/intensify after stepping-down or pausing controller therapy.

Research Recommendations:

|

Asthma exacerbations (attacks, episodes)

Asthma exacerbations are of critical importance, as they are associated with high morbidity, including emergency visits, hospitalizations and occasional mortality (132, 133). While detailed criteria for assessment of severity are proposed (Table 5), there are no objective criteria for the definition of an exacerbation and/or its differentiation from lack of control. The terminology is variable and the terms ‘exacerbation’, ‘attack’, ‘episode’ or ‘seizure’ (as translated from Japanese) are used almost interchangeably. The optional use of the adjectives ‘acute’ and ‘severe’ suggest that subacute and less severe episodes may also be within the limits of the concept. A formal definition is only suggested by GINA<5. There are descriptive definitions in GINA, NAEPP and AAMH. SIGN includes different algorithmic definitions according to severity (near-fatal asthma, life-threatening asthma, acute severe asthma, moderate asthma exacerbation, brittle asthma). No definitions are proposed in JGPA and PRACTALL. The acute or subacute and progressive nature of symptom intensification is generally highlighted. It is also generally accepted that the measurement of the associated reduction in airflow is preferable to symptoms in objective assessment. The use of oral steroids is a marker of the presence and/or severity of an exacerbation and has been proposed as part of its definition (134). However, medication use is a result of the exacerbation and therefore cannot formally define it without generating a vicious circle. Taking the above into account, a working definition is shown in Box 3.

Table 5. Assessment of Exacerbation Severity.

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Very severe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheeze | Variable | Moderate to loud | Loud – both on inhalation and exhalation | Often quiet |

| Breathlessness | Walking | At rest | At rest/sits upright | |

| Speaks in | Sentences | Phrases | Words | Unable to speak |

| Accessory muscle use | No | common | marked | paradoxical |

| Consciousness | Not affected | Not affected | Agitated, confused | |

| Respiratory rate | Slightly increased | Increased | Highly increased | Undetermined |

| Pulse | <100 | <140 (depending on age) | >140 | bradycardia |

| PEF (% of predicted or personal best) | >60-70% | 40-70% | <40% | <25% |

| SaO2 (% on air) | >94-95% | 90%-95% | <90% | |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | <42 | <42 | >=42 | |

Box 3 – Asthma exacerbation definition.

An exacerbation of asthma is an acute or subacute episode of progressive increase in asthma symptoms, associated with airflow obstruction

Exacerbations can be of varying severity, from mild to fatal, usually graded in 3 or 4 categories, from mild to life-threatening. Severity is assessed based on clinical presentation and objective measures (Table 5). Such classification may be difficult to apply in infants and pre-school children due to the lack of lung function assessment.

Exacerbation management (Box 4) can take place in different settings: at home, the doctor’s office, emergency unit, hospital or intensive care unit, largely in relation to severity, timing, availability and organisation of medical services.

Box 4 – Key points in asthma exacerbation treatment.

Bronchodilation: inhaled salbutamol, 2–10 puffs, or nebulized 2.5–5mg, every 20’ for the first hour, and according to response thereafter

-

➢

Ipratropium, 2–8 puffs, or nebulized 0.25–0.5mg, can be added to salbutamol

-

➢

If there is no improvement children should be referred to a hospital

Oxygen supplementation: aim at SaO2 > 95%

Systemic corticosteroids: oral prednisolone 1–2mg/kg/24h, usually for 3–5 days

At the hospital or ICU, if necessary, consider:

-

➢

IV beta-2 agonists, IV aminophylline, IV magnesium sulphate, helium-oxygen mixture

Bronchodilation is the cornerstone of exacerbation treatment (Evidence A); it should already start at home, as part of the asthma action plan, and should also be the first treatment measure in the emergency department (ED), immediately following severity assessment. Salbutamol inhaled at doses ranging from 2–10 puffs (200–1000µg), every 20 minutes for the first hour, given via MDI-spacer (nebulized also possible), is recommended. The addition of ipratropium bromide may lead to some additional improvement in clinical symptoms (Evidence A–B). The response should be assessed after the first hour; if not satisfactory the patient should be referred to a hospital (if at home) and the next level of therapy should be given.

Administration of supplemental oxygen is important to correct hypoxemia (Evidence A), with parallel O2 saturation monitoring. In severe attacks PCO2 levels may also need to be monitored.

Systemic corticosteroids, preferably oral, are most effective when started early in an exacerbation (Evidence A). The recommended dose is prednisolone 1–2mg/kg/day, up to 20mg in children <2years and up to 60mg in older children, for 3–5 days. It is pointed out however, that some recent studies showed negative results using the lower dose. Whether oral steroids should be initiated by parents at home is debated; if this happens it should be closely monitored by the prescribing physician. Very high dose inhaled steroids may also be effective either during the exacerbation or pre-emptively after a common cold (135, 136); however, they are not generally recommended to substitute systemic ones, although some experts feel that this may be an option. There is also some evidence for a modest pre-emptive effect of montelukast (137), however this is not currently recommended.

Additional measures at the hospital and/or the intensive care unit include continuous inhaled beta-2 agonists, intravenous bronchodilators such as salbutamol, and aminophylline (Evidence B). There is little or no evidence on magnesium sulphate or helium-oxygen mixture in children, however these could be options in cases not responding to the above treatments.

Research Recommendations:

|

Conclusions

Despite significant improvements in our understanding of various aspects of childhood asthma, as well as major efforts in producing high quality guidelines and/or consensus documents to support management, millions of patients worldwide continue to have suboptimal asthma control (138), possibly due to suboptimal treatment (139). Regardless of some variability in specific recommendations, wording and structure, all the major documents providing advice for best clinical practice in pediatric asthma management, point towards the same core principles and agree among the majority of their choices. However, implementation of such guidelines and access to standard asthma therapy for children remains challenging in many areas of the world.

It is expected, by increasing the accessibility and promoting dissemination of these core principles, in parallel to continued efforts for evaluating and incorporating evidence into improved guidelines, that we will be able to help improve the quality of life of children with asthma and to reduce the burden of this contemporary epidemic. Further understanding of the underlying pathophysiology and improved classification of subtypes may lead to more effective personalized care. Local adaptation of the above principles will also contribute to the same direction (1).

References

- 1.Kupczyk M, Haahtela T, Cruz AA, Kuna P. Reduction of asthma burden is possible through National Asthma Plans. Allergy. 2010;65(4):415–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lotvall J, Pawankar R, Wallace DV, Akdis CA, Rosenwasser LJ, Weber RW, et al. We call for iCAALL: International Collaboration in Asthma, Allergy and Immunology. (1398–9995 (Electronic)) doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asthma Management Handbook. [accessed Mar 2011];National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne. 2006 Available from: http://www.nationalasthma.org.au/cms/index.php.

- 4.From the Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2011 Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org.

- 5.From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma in Children 5 Years and Younger. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2009 doi: 10.1002/ppul.21321. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Nishimuta T, Kondo N, Hamasaki Y, Morikawa A, Nishima S. Japanese guideline for childhood asthma. Allergol Int. 2011;60(2):147–169. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.11-rai-0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Third Expert Panel on the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US); 2007. Aug, Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacharier LB, Boner A, Carlsen KH, Eigenmann PA, Frischer T, Gotz M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: a PRACTALL consensus report. Allergy. 2008;63(1):5–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.British Guideline on the Management of Asthma: a national clinical guideline. British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadad AR, Moher M, Browman GP, Booker L, Sigouin C, Fuentes M, et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on treatment of asthma: critical evaluation. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):537–540. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yunginger JW, Reed CE, O'Connell EJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, O'Fallon WM, Silverstein MD. A community-based study of the epidemiology of asthma. Incidence rates, 1964–1983. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1992;146(4):888–894. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearce N, Ait-Khaled N, Beasley R, Mallol J, Keil U, Mitchell E, et al. Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Thorax. 2007;62(9):758–766. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.070169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wennergren G, Ekerljung L, Alm B, Eriksson J, Lotvall J, Lundback B. Asthma in late adolescence--farm childhood is protective and the prevalence increase has levelled off. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(5):806–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sackesen C, Birben E, Soyer OU, Sahiner UM, Yavuz TS, Civelek E, et al. The effect of CD14 C159T polymorphism on in vitro IgE synthesis and cytokine production by PBMC from children with asthma. Allergy. 2011;66(1):48–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tesse R, Pandey RC, Kabesch M. Genetic variations in toll-like receptor pathway genes influence asthma and atopy. Allergy. 2011;66(3):307–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tischer CG, Hohmann C, Thiering E, Herbarth O, Muller A, Henderson J, et al. Meta-analysis of mould and dampness exposure on asthma and allergy in eight European birth cohorts: an ENRIECO initiative. Allergy. 2011;66(12):1570–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sporik R, Holgate ST, Platts-Mills TA, Cogswell JJ. Exposure to house-dust mite allergen (Der p I) and the development of asthma in childhood. A prospective study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(8):502–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199008233230802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahn U, Lau S, Bergmann R, Kulig M, Forster J, Bergmann K, et al. Indoor allergen exposure is a risk factor for sensitization during the first three years of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(6 Pt 1):763–769. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)80009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan-Yeung M, Ferguson A, Watson W, Dimich-Ward H, Rousseau R, Lilley M, et al. The Canadian Childhood Asthma Primary Prevention Study: outcomes at 7 years of age. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodcock A, Lowe LA, Murray CS, Simpson BM, Pipis SD, Kissen P, et al. Early life environmental control: effect on symptoms, sensitization, and lung function at age 3 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):433–439. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-083OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horak F, Jr, Matthews S, Ihorst G, Arshad SH, Frischer T, Kuehr J, et al. Effect of mite-impermeable mattress encasings and an educational package on the development of allergies in a multinational randomized, controlled birth-cohort study -- 24 months results of the Study of Prevention of Allergy in Children in Europe. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(8):1220–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro-Rodriguez JA, Garcia-Marcos L, Sanchez-Solis M, Perez-Fernandez V, Martinez-Torres A, Mallol J. Olive oil during pregnancy is associated with reduced wheezing during the first year of life of the offspring. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(4):395–402. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozzetto S, Carraro S, Giordano G, Boner A, Baraldi E. Asthma, allergy and respiratory infections: the vitamin D hypothesis. Allergy. 2012;67(1):10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez FD. New insights into the natural history of asthma: primary prevention on the horizon. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(5):939–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Busse WW, Lemanske RF., Jr Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(5):350–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snijders D, Agostini S, Bertuola F, Panizzolo C, Baraldo S, Turato G, et al. Markers of eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation in bronchoalveolar lavage of asthmatic and atopic children. Allergy. 2010;65(8):978–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holgate ST. Epithelium dysfunction in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1233–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.025. quiz 1245–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung KF. Airway smooth muscle cells: contributing to and regulating airway mucosal inflammation? Eur Respir J. 2000;15(5):961–968. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15e26.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamid Q, Tulic M. Immunobiology of asthma. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:489–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson DS. The role of the mast cell in asthma: induction of airway hyperresponsiveness by interaction with smooth muscle? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xepapadaki P, Papadopoulos NG, Bossios A, Manoussakis E, Manousakas T, Saxoni-Papageorgiou P. Duration of postviral airway hyperresponsiveness in children with asthma: effect of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(2):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joos GF. The role of neuroeffector mechanisms in the pathogenesis of asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2001;1(2):134–143. doi: 10.1007/s11882-001-0081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holgate ST, Polosa R. The mechanisms, diagnosis, and management of severe asthma in adults. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):780–793. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69288-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fixman ED, Stewart A, Martin JG. Basic mechanisms of development of airway structural changes in asthma. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(2):379–389. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00053506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watelet JB, Van Zele T, Gjomarkaj M, Canonica GW, Dahlen SE, Fokkens W, et al. Tissue remodelling in upper airways: where is the link with lower airway remodelling? Allergy. 2006;61(11):1249–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malmstrom K, Pelkonen AS, Malmberg LP, Sarna S, Lindahl H, Kajosaari M, et al. Lung function, airway remodelling and inflammation in symptomatic infants: outcome at 3 years. Thorax. 2011;66(2):157–162. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.139246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bossley CJ, Fleming L, Gupta A, Regamey N, Frith J, Oates T, et al. Pediatric severe asthma is characterized by eosinophilia and remodeling without T(H)2 cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, Wiecek EM, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, et al. A longitudinal, population-based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(15):1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(3):133–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bisgaard H, Bonnelykke K. Long-term studies of the natural history of asthma in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(2):187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.011. quiz 198-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Covar RA, Strunk R, Zeiger RS, Wilson LA, Liu AH, Weiss S, et al. Predictors of remitting, periodic, and persistent childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):359–366. e353. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruotsalainen M, Piippo-Savolainen E, Hyvarinen MK, Korppi M. Adulthood asthma after wheezing in infancy: a questionnaire study at 27 years of age. Allergy. 2010;65(4):503–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, Wright AL, Martinez FD. A clinical index to define risk of asthma in young children with recurrent wheezing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(4 Pt 1):1403–1406. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leonardi NA, Spycher BD, Strippoli MP, Frey U, Silverman M, Kuehni CE. Validation of the Asthma Predictive Index and comparison with simpler clinical prediction rules. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(6):1466–1472. e1466. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Sossa-Briceno MP, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Discriminative properties of two predictive indices for asthma diagnosis in a sample of preschoolers with recurrent wheezing. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46(12):1175–1181. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brand PL. The Asthma Predictive Index: not a useful tool in clinical practice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1):293–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger D, White D, Lemanske RF, Jr, Sorkness CA. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):426–432. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frey U. Forced oscillation technique in infants and young children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005;6(4):246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bisgaard H, Nielsen KG. Plethysmographic measurements of specific airway resistance in young children. Chest. 2005;128(1):355–362. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartz LB, Delgado L, Craig T, Bonini S, Carlsen KH, Casale TB, et al. Exercise-induced hypersensitivity syndromes in recreational and competitive athletes: a PRACTALL consensus report (what the general practitioner should know about sports and allergy) Allergy. 2008;63(8):953–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cockcroft D, Davis B. Direct and indirect challenges in the clinical assessment of asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103(5):363–369. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60353-5. quiz 369-372, 400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Niggemann B, Gruber C, Wahn U. Perennial allergen sensitisation early in life and chronic asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):763–770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]