Abstract

Objective

To report an innovative combination of two surgical procedures to treat patients with erectile dysfunction and penile deviation, arising from advances in penile anatomy.

Patients and methods

From October 1998 to October 2011, 132 men (aged 23–39 years) underwent penile venous stripping and corporoplasty. Of these, 37 were allocated to a transverse and 95 to a longitudinal group, with an infrapubic transverse or pubic median longitudinal approach, respectively. The abridged five-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) and cavernosography were used for assessment, as necessary. Under acupuncture-aided local anaesthesia, and after a circumferential incision, the deep dorsal vein and cavernous veins were completely stripped, with 6-0 Nylon sutures for ligation, followed by tunical surgery for correcting the penile shape.

Results

In the transverse and longitudinal groups the mean (SD) duration of surgery was 4.6 (0.2) and 4.8 (0.3) h, respectively. Before surgery the mean (SD) IIEF-5 score was 9.4 (2.3) and 9.6 (2.1), which increased to 20.6 (2.4) and 20.8 (2.7), respectively, after surgery. The penile shape (<15°) was deemed satisfactory in 92% (34/37) and 96% (91/95) of patients in the transverse and longitudinal groups, respectively. The cavernosograms consistently showed a good penile shape. There were significant differences in the mean (SD) duration of penile oedema, at 3.2 (1.6) vs. 11.9 (2.1) days, the overall satisfaction rate and the prevalence of hypertrophied scarring (all P < 0.001).

Conclusion

This combination of unique penile venous stripping with a pubic median longitudinal approach and an anatomy-based corporoplasty is ideally suited to the simultaneous restoration of penile erectile function and morphological reconstruction.

Abbreviations: ED, erectile dysfunction; VOD, veno-occlusive dysfunction; PDE1, prostaglandin-E1; IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function; DDV, deep dorsal vein; CV, cavernous vein

Keywords: Penile deviation, Veno-occlusive dysfunction, Venous stripping, Erectile dysfunction, Corporoplasty

Introduction

In penile corporoplasty for optimizing penile shape, maintaining the anatomical integrity of the tunica is a prerequisite for preserving erectile function, as well as optimizing penile morphology [1]. Various surgical methods have been proposed in attempts to model the ideal penile shape. The most commonly applied are Nesbit’s procedure [2] and the recently introduced tunical plication [3], both because of their simplicity and better reproducibility. Unfortunately, these are not sustainable if the tunical anatomy is still considered as a single inner circular layer [4]. With the improved understanding of the three-dimensional nature of the tunical anatomy, in which an additional outer longitudinal layer is responsible for providing strength [5], we adopted the use of 6-0 Nylon for ligation [6]. Consequently, a more favourable outcome has resulted, with negligible morbidity since 1997 [7].

In previous reports few surgical interventions have caused as much controversy as penile venous surgery for restoring erectile function. For over a century its merit has remained a matter of intense dispute and thus it has almost been abandoned [8]. Many urologists believe that venous surgery is only indicated for <1% of patients with erectile dysfunction (ED) because the pathophysiology is intracorporeal fibrosis [9]. However, many studies show that veno-occlusive dysfunction (VOD), previously termed venous leakage or venous incompetence, might be 100 times more prevalent in patients with ED and even in those with ED ascribed to penile arterial insufficiency [10,11]. Thus it is uncertain why this surgery is rare for men with ED, whose response to venous surgery is good if some 90% of the ED results from leaky veins.

We have reported positive outcomes with our surgical approaches since 1986 [12], ultimately with an approved patent in 2012 [13], and have published human cadaveric studies to support these methods [14]. Both penile functional and corporoplasty surgery are intrinsic and challenging. We have expertise in ambulatory surgery facilitated by local anaesthesia. This has been underpinned by the encouraging outcomes, minimal complications, and negligible morbidity resulting from a meticulous preservation of the penile physiology, which is critical for avoiding complications after surgery, particularly short-term oedema and the highly contentious long-term phenomenon of penile shortening. Here we report a method for simultaneous procedures on an ambulatory basis, the techniques used being refined over the course of extensive clinical practice and cadaveric studies of the penile tunical and venous anatomy [15].

Patients and methods

Patients were only included in the study if they were aged <40 years, had undergone other less invasive treatments for ED that had failed, were free of chronic systemic disease (e.g. diabetes mellitus, liver disease, renal failure, hormonal insufficiency, or psychoneurotic disorders), and if they were not excluded from undergoing cavernosography, based on other obvious causes, e.g., major pelvic surgery. Patients who had arterial insufficiency, screened by Doppler ultrasonography and a prostaglandin-E1 (PGE1) test, were also excluded. Between October 1998 and October 2011, 132 men (aged 23–39 years), with ED associated with VOD and penile deviation, underwent simultaneous penile venous stripping and corporoplasty. In men with a penile deviation, it was ⩾30°, and the erectile corporeal length was >18 cm, as assessed by cavernosography. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for the risk of penile shortening of the convex tunica by 1–2 cm after the corporoplasty.

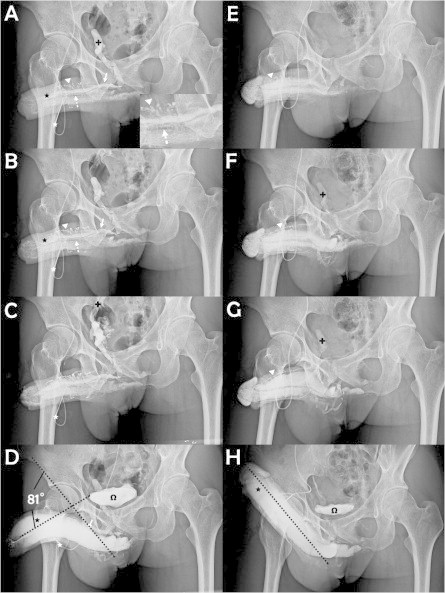

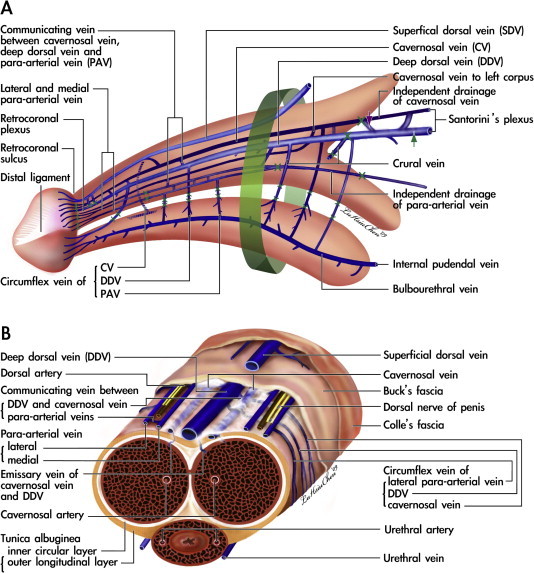

Of these men, 37 before August 2002 had a circumferential incision plus an infrapubic transverse approach (Fig. 1A), which after September 2002 was replaced by a pubic median longitudinal approach (Fig. 1B) for a short cut accessing the deep-seated venous channel, in 95 men. These men were allocated to a transverse and longitudinal group, respectively. The abridged five-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) was used as the standard questionnaire, while the diagnosis of VOD was typically made after a dual pharmaco-cavernosography including a PGE1 test. The cavernosography was carried out using an intracavernous injection with 120 mL of 30% contrast medium (Omipaque, GE Healthcare, USA) solution via a 19-G scalp needle firmly fixed to the distal-lateral portion of the penis. The first set of cavernosograms (Fig. 2A–C) was taken to show the venous anatomy of the penis. The second set was taken 3 min later, after an intracavernous injection with 20 μg PGE1, to distinguish the venous channels involved in VOD (Fig. 2D and H) during erection. Arterial pulsatile function and PGE1 responses were assessed simultaneously. The direction and degree of penile deviation were recorded. Surgery was conducted under acupuncture-aided local anaesthesia on an ambulatory basis. Neither a Bovie electrocoagulator nor a suction apparatus was used. The duration of the surgery was recorded from the point at which the local aesthetic was injected, until the final suturing of the skin. All patients gave their informed consent.

Figure 1.

An illustration of a transverse infrapubic and a median longitudinal pubic skin incision. (A) A transverse infrapubic skin incision (arrow) with a circumferential approach (arrowhead) was used before August 2002. (B) A median longitudinal pubic skin incision (arrow) with a circumferential approach (arrowhead) was used afterwards.

Figure 2.

Cavernosography showing the surgical outcomes. (A) A cavernosogram taken immediately after an intracavernous injection with 50% contrast medium into the sinusoids (black asterisk) of the corpora cavernosa (CC) via a 19-G scalp needle (white asterisk). The DDV (white arrow) was depicted, with the CVs (dotted arrow) beneath, whereas the para-arterial veins (PAVs, white arrowhead) had a zigzag appearance. The internal pudendal vein (black cross) appeared rapidly. (B) As the injection (white asterisk) continued both the DDV (white arrow), CVs (dotted arrow), PAVs (white arrowhead) and CC (black asterisk) became pronounced. (C) The injected solution drained rapidly back to the level of internal iliac vein (arrow) which continues the internal pudendal vein. (D) A film taken 15–30 min later after an injection with 20 μg of PGE1. The depicted DDV (white arrow) documented the venous leakage despite the rigid erection; the urinary bladder (omega) is shown. A penile deviation of 81° was estimated. (E) A film of a patient with a similar condition to that in panel A at 1 year after surgery; the CC (black asterisk) was readily inflated, while neither the DDV (white arrow) nor the CVs (dotted arrow) were apparent, but the PAVs (white arrowhead) were smaller. (F) Likewise, comparing with the view in panel B, there were no further leaky veins because the depiction of the internal pudendal vein (black cross) was minimal. (G) For comparison with panel C, the internal iliac vein (black cross) was apparent. (H) A full erection was readily induced after an injection with 10 μg PGE1. The CC (black asterisk) and bladder (omega) were inflated, as compared with panel D. The penile became straight, apparently at an ideal erection angle (dotted line), which should sustain a buckling pressure.

For the acupuncture-assisted local anaesthesia, lidocaine (0.8%, 50 mL) with adrenaline was administered at a site between the suspensory ligament and the pubic angle, through a 23-G disposable needle (with the bevel maintained parallel to the longitudinal axis of the body, to avoid harming the dorsal nerve). To administer a bilateral block of the proximal dorsal nerves, the penile shaft was pulled away from the body axis and the solution was injected into the penile hilum in three sites, using a 10-mL syringe. While the location of the needle tip was verified digitally, the injected lidocaine was infiltrated topically at the scrotum and at the junction between the corpus spongiosum and corpora cavernosa. Supplementary injections were provided if the patient continued to report pain (although the dose of lidocaine was strictly limited to 400 mg). Acupuncture was used as an adjuvant to local anaesthesia and was carried as described previously [16].

Penile venous stripping and tunical surgery

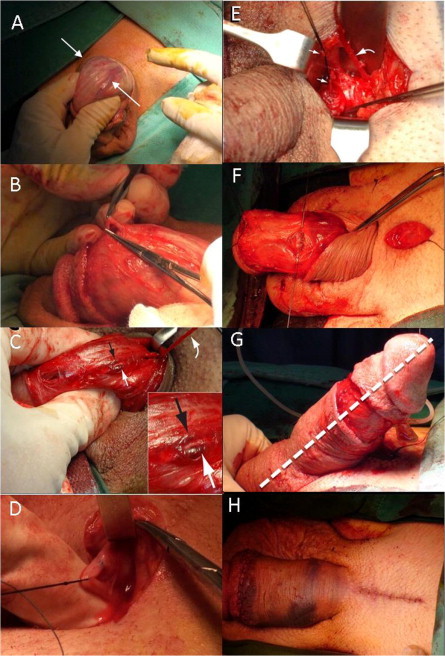

A template detailing the refined penile venous stripping surgery was referred to throughout (Fig. 3). A circumferential incision was first made, followed by a more-extensive degloving of those tissue layers superficial to Colles’ fascia. The visibility of the deep dorsal vein (DDV, Fig. 4A) can be enhanced by squeezing the corpora cavernosa, as can be done for the cavernous veins (CVs). First, the DDV was manipulated (Fig. 4B), stripped and then ligated at the tunical level up to the penile base, with a 6-0 Nylon suture, while the CVs were readily apparent (Fig. 4C). The deep-seated venous tissue was accessed by a transverse pubic skin incision in 37 men in the transverse group, and then a pubic median longitudinal skin incision was used in 95 men in the longitudinal group to facilitate the venous stripping.

Figure 3.

A template for the complete removal of the erection-related veins in a physiological approach to the human penis. (A) Lateral view: the erection-related veins surround the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa. These include the DDV, CVs and PAVs. The DDV in the median position receives the blood of the emissary veins from the CC and of the circumflex vein from the corpus spongiosum. It is flanked by a pair of CVs which lie in a deeper position. Bilaterally, each dorsal artery is, respectively, sandwiched by its corresponding medial and lateral PAVs. Note that the lateral PAV merges with the medial one proximally. The deeper colour of the veins indicates a deeper group of the vasculature. At the penile hilum, communicating veins of the DDV and CV are encountered first (purple arrow), denoting the erection veins leaving the CC, and finally (green arrow), signifying the completeness of venous stripping. A 1.0-cm segment (green cuff) around the penile base must not be separated, to prevent penile shortening resulting from penile retraction among the layered tissues. The borders of the ligatures of venous stumps are marked. (B) A cross-section of the mid-portion: The DDV and PAVs are in the same imaginary arc, whereas the CVs are tucked at deeper positions with a separate perivascular sheath. Note that there are seven veins rather than that traditionally reported one, although it becomes four at the level of penile hilum because there is a merging in each pair of the nomenclature veins.

Figure 4.

Photographs of the surgical process. (A) A circumferential incision was made 1 cm proximal to the retrocoronal sulcus. The channels (white arrow) of the DDV are easily identifiable. Its visibility can be further enhanced by light compression of the corpora cavernosa. (B) The DDV was manipulated. (C) Serving as a guide, the DDV (curved arrow, held by a mosquito haemostat) was then thoroughly stripped and ligated with 6-0 Nylon sutures using a pull-through manoeuvre. It was sandwiched by the left (white arrow) and right (black arrow) CVs. (D) A median longitudinal pubic incision was made to facilitate the stripping procedure. Note that one deep-seated proximal branch was tagged with a black silk suture. (E) The DDV (curved arrow) and CVs (arrows) were stripped proximally until the infrapubic angle was encountered. (F) A tunical corporotomy was performed proximally (arrow) using a 6-0 Nylon suture. (G) An artificial erection was induced to show the ideal penile shape (dotted line) after the corporoplasty via a 19-G scalp needle. (H) Both the circumferential (white arrow) and median longitudinal pubic wounds (black cure arrow) were approximated with a 5-0 chromic sutures.

The paired proximal stumps of the DDV (Fig. 4D) and CVs (Fig. 4E) which served as a guide, were then thoroughly stripped and ligated at the end of the stripping procedures of these two venous systems. After the neurovascular bundle was freed and tagged, a modified Nesbit procedure was used, with at least an elliptical excision of the contorted tunica, as well as a tunical patch. The corporotomy was precisely fashioned with individual collagen bundles and 6-0 Nylon sutures (Fig. 4F), using a loupe. An artificial erection was routinely used to assess the penile shape before and after (Fig. 4G) tunical surgery, via a 19-G scalp needle.

Finally, the circumferential and the pubic wounds were closed (Fig. 4H) going from the Colles’ fascia to the dermis, and finally the skin layer was closed using 5-0 chromic sutures, with an assistant applying consistent stretching to the penile shaft. The circumferential wound was similarly closed. A compression dressing, encircling the length of the stretched penile shaft, was then applied. Cavernosographic (Fig. 2H) and IIEF data were then collected every 6 months over the follow-up.

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean (SD) and compared using Student’s t-test and a paired t-test after being logarithmically transformed, with a statistical significance indicated at P < 0.05.

Results

The details of 132 patients are given in Table 1. In the transverse and longitudinal groups the mean operative duration was 4.6 (0.2) and 4.8 (0.3) h, respectively. Of the patients, 123 (93.2%) required two supplementary injections of local anaesthetic, while three required three injections. The mean (SD, range) follow-up was 7.3 (1.3, 1.0–13.0) years.

Table 1.

The features of the 132 patients who had a penile corporoplasty and reconstruction for erectile function.

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Group |

Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transverse | Longitudinal | |||

| N patients | 37 | 95 | 132 | |

| Age (years) | 35.6 (4.7) | 32.3 (4.8) | – | NS |

| IIEF-5 score | ||||

| Before | 9.4 (2.3) | 9.6 (2.1) | – | NS |

| After | 20.6 (2.4) | 20.8 (2.7) | – | NS |

| Operative duration (h) | 4.6 (0.2) | 4.8 (0.3) | – | NS |

| Frenular oedema (days) | 11.9 (2.1) | 3.2 (1.6) | – | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with | ||||

| Surgery | 23 (62) | 93 (98) | 116 (87.9) | <0.001 |

| Morphology | 34 (92) | 91 (96) | 125 (94.7) | NS |

| Infection | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 | NS |

| Hypertrophied scar | 4 (11) | 1 (1) | 5 | <0.001 |

Univariate comparison by Student’s t-test for continuous variables, or chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and Yate’s correction for discontinuous variables, as necessary. NS, not significant.

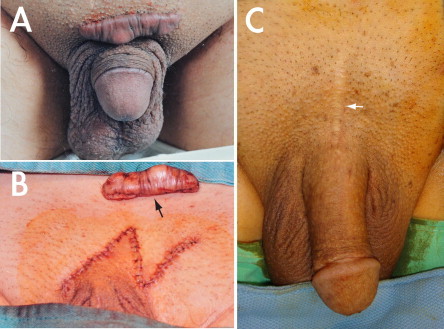

The duration of frenular oedema after surgery, at 11.9 (2.1) vs. 3.2 (1.6) days, patient satisfaction rate of the surgery (62% vs. 98%) and hypertrophied scar (Fig. 5A and B) rate (12% vs. 1%), respectively, were significantly different (P < 0.001) in favour of the longitudinal group (Fig. 5C). There was no difference in the infection rate after surgery and operative duration in both groups. The difference in erectile function was significant, as assessed by the IIEF-5 scores before, of 9.4 (2.3) and 9.6 (2.1), and after surgery, of 20.6 (2.4) and 20.8 (2.7), respectively (both P < 0.001). However, there was no difference between the two surgical approaches.

Figure 5.

A comparison of wound healing after the two approaches. (A) A hypertrophied scar of a 45-year-old patient who had a transverse infrapubic incision in 1999. (B) After excision (arrow), the scar was treated with Z-plasty. (C) A 67-year-old patient who had undergone this surgery via a median longitudinal pubic incision (white arrow) in May 2002. The operation was uneventful, as was the scar healing.

Intraoperative cavernosography was carried out in five patients, and follow-up cavernosograms were taken in 23 (17.4%), of whom 13 (10%) requested confirmation of venous removal due to a perceived temporary lack of response, while five (4%) requested an objective comparison despite the surgery proving satisfactory. A satisfactory penile shape (<15°) was achieved in 92% (34/37) and 96% (91/95) patients in the transverse and longitudinal groups, respectively. The follow-up cavernosograms consistently showed a good penile shape. Overall, 94.7% of the patients (125/132) reported a satisfactory penile shape.

Discussion

In 1986 we carried out transverse infrapubic skin incisions and median longitudinal incisions of the penile base (Fig. 1) on 28 and four patients, respectively [17]. As a result of the long-term follow-up, we showed that the latter approach, carried out in conjunction with an inside-out manoeuvre, in which the penile shaft was released from the longitudinal incision (similar to the way in which a polo shirt is removed from the body trunk), provided a better outcome [16]. Although at that time the former approach was more widely favoured, we found that it resulted in greater scarification of the lymphatic vessels, increasing the likelihood of postoperative lymphoedema and scar hypertrophy, which could be treated with a Z-plasty (Fig. 5B). With either surgical approach the surgeon could access the confluent trunk of the DDV and the circumflex veins in the pendulous portion of the penis, but we sought a shorter approach for direct access to the affected veins at the retrocoronal level.

With any type of operation the approach taken greatly determines the functional outcomes and anatomical integrity after surgery, and this is especially true of surgery involving a highly specialized, multilayered structure like the penis. The anatomical configuration and histological components of the human penis vary considerably with location and function. Based on anatomical studies [18], we chose a circumferential incision for this purpose. Thus a physiologically compatible approach, consisting of a circumferential and a median longitudinal incision, was used in this study. Also, recent evidence indicates that circumcision can reduce an individual’s likelihood of contracting HIV infection by 60% [19]. Accordingly, the benefits of the circumferential approach are manifold; not only can there be a simultaneous circumcision, but the affected veins can be accessed without endangering the lymphatic vessels, arteries, nerves, or any other vulnerable, multilayered structures.

The clinical guidelines, as established after an analysis by the AUA in 1996, assert that venous surgery is not justified for routine use. Criticism was levelled at its perceived lack of long-term effectiveness, with its potential for causing permanent deformity and irreversible numbness, which were deemed unacceptable complications. This verdict, along with these seemingly unavoidable adverse effects, has led to the virtual abandonment of the practice by most urologists. However, we maintain that complications resulting from fibroskeleton and nerve involvement are fully preventable, as the site of venous surgery is exclusively the veins. It was this notion that originally prompted us to study penile anatomy through dissection, staining and microscopy. We were then able to avoid these unacceptable complications.

Experience indicates that, compared with other vascular structures within the penis, the sinusoidal tissues are particularly susceptible to excessive bleeding after injury. However, the high incidence of fibrosis and deformity associated with the use of a Bovie during penile surgery has led us to conclude that electrocoagulation is a hazardous haemostatic method for use in operations involving the penis [20]. A better approach entails keeping the stripped venous channels under tension to ensure closure of the lumen. However, it is important that the venous plexus itself is far too susceptible to avulsion to be manipulated so directly. Nevertheless, the use of a Bovie has the potential to damage the sinusoidal tissues in the corpora cavernosa, compromising their extensibility, and thereby impairing erectile function. Likewise, electrocautery can injure extracavernous tissues and cause fibrosis, potentially resulting in penile deformity. Also, it is crucial that during wound approximation of Buck’s fascia, Colles’ fascia, and dermal layers, an assistant maintains tension on the glans penis (at the 3 and 9 o′clock positions) to maintain the sliding property of each layer, thus minimizing the possibility of penile shortening after surgery.

The first corporoplasty was reported as early as 1965 [2], although the collagen bundles of the outer longitudinal tunica albuginea, the target tissues operated on, were only elucidated as late as 1992 [5]. Thus the surgical outcome might not be optimal if the attending surgeon fails to understand this tunical anatomy. Thereafter, a corporoplasty was never considered to be an easy urological surgery. In our long term practice, a modified Nesbit procedure ought to be more suitable.

The tunical discrepancy is usually assessed by ‘rule of thumb’ at the surgeon’s discretion, but recently an engineering formula was developed. Thus, both the dimensions and location of the penile curvature correction can depend on a more scientific formula rather than just relying on ‘trial and error’. Further study is warranted.

Our technique for local anaesthesia can be easily mastered, as the penile shaft is devoid of fatty tissue and surrounded by a well-defined, layered fascia, and the tunica albuginea, which serve as excellent reference points for placing the needle (as long as the attending surgeon has an adequate structural knowledge of the fibroskeleton). A single dose of local anaesthesia applied in this way can last for up to 4 h. Most patients required no supplementary injections. This refined method enhances surgery, which achieves its purpose with a small risk of morbidity, and on an ambulatory basis.

In conclusion, this innovative surgery appears to deliver a favourable outcome, although a larger sample and longer-term follow-up are necessary. It entails a technically challenging combination of two surgical procedures, i.e., a unique method of penile venous stripping and an anatomy-based corporoplasty. A circumferential incision plus a pubic median longitudinal approach appear to be an optimal surgical technique for restoring penile erectile function and for morphological reconstruction.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Benedict S.A. Murrell for his English editing, Ms. Hsiu-Chen Lu for illustrations and photography and Mrs. Nicola Chen and Luan-Hua Ho for their preparation of photographs for this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- 1.Hsieh C.H., Chen H.S., Lee W.Y., Chen K.L., Chang C.H., Hsu G.L. Salvage penile tunical surgery. J Androl. 2010;31:450–456. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.008573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nesbit R.M. Congenital curvature of the phallus: report of three cases with description of corrective operation. J Urol. 1965;93:230–232. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63751-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S.S., Meng E., Chuang F.P., Yen C.Y., Chang S.Y., Yu D.S. Congenital penile curvature. Long-term results of operative treatment using the plication procedure. Asian J Androl. 2004;6:273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eardley I., Sethia K. Anatomy and physiology of erection. In: Eardley I., Sethia K., editors. Erectile dysfunction – current investigation and management. Mosby; London: 2003. pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu G.L., Brock G.B., Martinez-Pineiro L., Nunes L., von Heyden B., Lue T.F. The three-dimensional structure of the tunica albuginea: anatomical and ultrastructural levels. Int J Impot Res. 1992;4:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez L.R. The double-eyelid operation in the oriental in Hawaii. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1960;25:257–264. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu G.L., Chen S.H., Weng S.S. Outpatient surgery for the correction of penile curvature. Br J Urol. 1997;79:36–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.02988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montague D.K., Barada J.H., Belker A.M., Levine L.A., Nadig P.W., Roehrborn C.G. Clinical guidelines panel on erectile dysfunction: summary report on the treatment of organic erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 1996;156:2007–2011. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nehra A., Goldstein I., Pabby A., Nugent M., Huang Y.H., De las Morenas A. Mechanism of venous leakage: a prospective clinico-pathological correlation of corporeal function and structure. J Urol. 1996;156:1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs A.M., Mehringer C.M., Rajfer J. Anatomy of penile venous drainage in potent and impotent men during cavernosography. J Urol. 1989;141:1353–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elhanbly S., Abdel-Gaber S., Fathy H., El-Bayoumi Y., Wald M., Niederberger C.S. Erectile dysfunction in the smoker. A penile dynamic and vascular study. J Androl. 2004;25:991–995. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb03172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen S.C., Hsieh C.H., Hsu G.L., Wang C.J., Wen H.S., Ling P.Y. The progression of the penile vein: could it be recurrent? J Androl. 2005;26:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu GL. Physiological approach to penile venous stripping surgical procedure for patients with erectile dysfunction (Patent No: US 8,240,313,B2). Available from: http://www.google.com/patents/US20110271966.

- 14.Hsu G.L., Hung Y.P., Tsai M.H., Hsieh C.H., Chen H.S., Molodysky E. Penile veins are the principal component in erectile rigidity: a study of penile venous stripping on defrosted human cadavers. J Androl. 2012;33:1176–1185. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.112.016865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu G.L., Hsieh C.H., Wen H.S., Chen Y.C., Chen S.C., Mok M.S. Penile venous anatomy: an additional description and its clinical implication. J Androl. 2003;24:921–927. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb03145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu G.L., Chen H.S., Hsieh C.H., Lee W.Y., Chen K.L., Chang C.H. Clinical experience of a refined penile venous surgery procedure for patients with erectile dysfunction: is it a viable option? J Androl. 2010;31:271–280. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.008532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai T.C., Hsu G.L., Chen S.C., Wang C.L. Analysis of the results of reconstructive surgery for vasculogenic impotence. J Formos Med Assoc. 1988;87:182–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh C.H., Liu S.P., Hsu GL Chen H.S., Molodysky E., Chen Y.H. Advances in our understanding of mammalian penile evolution, human penile anatomy and human erection physiology: clinical implications for physicians and surgeons. Med Sci Monitor. 2012;18:RA118–RA125. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger J.N., Mehta S.D., Bailey R.C., Agot K., Ndinya-Achola J.O., Parker C. Adult male circumcision. Effects on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in Kisumu, Kenya. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2610–2622. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai V.F.S., Chang H.C., Liu S.P., Kuo Y.C., Chen J.H., Jaw F.S. Determination of human penile electrical resistance and implication on safety for electrosurgery of the penis. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2891–2898. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]