Abstract

Objectives

To describe the different approaches to the treatment of premature ejaculation (PE), with a final focus on integrated treatment, as conventional theories and therapies for PE are based on an organic or psychogenic dichotomy.

Methods

We list the principal hypotheses of the causes and therapy of PE on the basis of psychological and medical perspectives, after identifying all relevant studies available on Medline up to 2012.

Results

The cognitive feedback from PE can lead to a ‘performance anxiety’, which can combine with other conditions to further impair ejaculatory control. For these reasons, a psychological approach is always useful in treating PE, the most useful of which are sex therapy and behavioural therapy. For pharmacological treatment, reports suggest that dapoxetine (60 mg) significantly improves the control of the ejaculatory reflex, and it thus represents the first-line officially approved pharmacotherapy for PE.

Conclusions

A holistic approach which considers the biological, psychological and relational aspects is the advised treatment for PE. Integrated medical and psycho-sexological therapy requires a mutual understanding of and respect for the different disciplines involved in sexology. In this aspect two very important roles are those of the physician and the psychologist.

Abbreviations: PE, premature ejaculation; IELT, intravaginal ejaculation latency time; ED, erectile dysfunction.

Keywords: Premature ejaculation, Holistic approach, Integrated model, Dichotomy

Introduction

In male sexual dysfunction several new pathophysiological and therapeutic discoveries have led to a renewed attention on the lack of ejaculatory control [1]. Previously, rapid or premature ejaculation (PE) was considered to be a typically relational and psychological pathology [2]. Recent advances in the understanding of the importance and frequency of PE, insights into its organic and non-organic pathophysiology, and the efficacy of increasing pharmacological therapies have lead to new, integrated therapeutic alternatives from a modern psychosomatic and holistic perspective.

These new therapeutic alternatives (medical and psychological), together with the cooperation between basic researchers (geneticists, neurophysiologists, pharmacologists, and ethologists) and clinicians (endocrinologists, andrologists, psychologists and psycho-sexologists, psychiatrists, urologists, and gynaecologists), have made it possible to improve and/or restore an active sexual life to many dysfunctional couples, thus enhancing their overall quality of life.

In this review, we describe the different approaches to the treatment of PE, focusing on integrated treatment, as conventional theories and therapies for PE are based on an organic or psychogenic dichotomy. We examine the main hypotheses of the causes and therapy of PE on the basis of psychological and medical perspectives, after identifying all relevant studies available on Medline up to 2012 (Appendix A).

Symptom or disease?

As with all sexual disorders, PE is a symptom rather than a disease. From a clinical perspective this suggests that in any case of PE the disease behind the symptom must be carefully sought and, if possible, cured.

Common theories on PE are based on an organic or psychogenic dichotomy, with a particular focus on psychological causes. However, the adjective ‘psychogenic’ is inappropriate, because irrespective of the ultimate cause, lack of ejaculatory control is per se stressful and a source of psychological disturbances. All cases of PE are considered psychogenic, even where PE is a symptom of an organic cause.

Indeed, from a therapeutic perspective, pharmacological aids, with psychotherapy, are often useful for treating a patient with psycho-relational problems. Conversely, pharmacotherapy without psychological counselling that considers the patient’s personal and sexual history, and the profound effect that medical treatment might have on the couple, is often unsuccessful [3].

The history of PE

The control of the ejaculatory reflex represents an evolutionary and cultural advance for human sexuality. It is known that in animals ‘coitus citus’ has great survival value, e.g., in the primates the rapid deposition of semen protects the animal from extended exposure to predators. However, one of the main aims of human sexuality is pleasure, and men have learned to control ejaculation, to enhance their and their partner’s enjoyment. For this reason PE has a profound effect on relational and psychological health and therefore can be treated by psychotherapy of the couple.

The term ejaculatio praecox was introduced by the psychoanalyst Abraham [4], but until the first half of the 20th century, PE was not included in the list of sexual disorders. Kinsey et al. [5], in a survey of almost 20,000 Americans, found that 75% of men ejaculated within 2 min of penetration, and they rejected the notion that PE is a sexual dysfunction. By contrast, Shapiro [6] argued that PE might be the combination of a hyperanxious constitution with anatomical defects.

The relevance of PE as an important sexual dysfunction for single men and the couple was contemporary with the feminist revolution in the mid 1960s, and the ‘discovery’ of the female orgasm. The clinical approach to PE as a valid sexual disorder is linked to this important cultural change.

Sexology of PE: a psychological and neurobiological disorder

Some researchers consider that PE is not a psychological disorder but a neurobiological phenomenon [7], but the arguments sustaining this thesis are weak. Some psychological [8] and neurobiological positions are extreme, and compromise the growth of sexology and the patients’ well-being. The mind–body separation is obsolete in modern medicine [9]. Whilst it is clear that all psychological processes are regulated by brain function (somato-psychic evidence) it is also plain that all psychogenic dysfunctions involve organic processes (psychosomatic evidence). This holistic approach allows PE to be considered as a psycho-neuroendocrine and urological disorder affecting the couple.

The anatomy and physiology of ejaculation

To understand the pathogenesis, and psychological and pharmacological PE therapies, it is important to understand that normal male copulation culminates in three psychologically and physiologically distinct events:

-

1.

Emission: There is contraction of the smooth muscle cells of the male genital tract involving the testicular tubules, efferent ducts, the epididymis, and vasa deferentia, and the secretion of seminal fluid due to rhythmic contractions of the seminal vesicles and prostate.

-

2.

Ejaculation: A reflex response, not requiring cerebral input, which is triggered by the accumulation of semen in the bulbous urethra. The pelvic floor muscles actively collaborate to achieve ejaculation, with from three to seven contractions.

-

3.

Orgasm: A perceptual-cognitive event of pleasure that, in normal conditions, coincides with the time of ejaculation [10]. Even though principally controlled by the same sympathetic nerves, these three elements are separate from one another and provoke different psychological perceptions [11].

The neuropharmacology of ejaculation

Little information is available on the central control of ejaculation. The serotoninergic system acts as a suppressor of the ejaculatory reflex at the hypothalamic level [12]. By contrast, the dopaminergic pathway might act as an ejaculation stimulator through the D2 receptors [13].

PE is a symptom of the couple

One of the most important features of modern medical sexology as described by Masters and Johnson [14] is that the object of the sex therapy is not the individual with the sexual problem, but the couple. However, most new medical and surgical therapies for PE or delayed ejaculation, and for erectile dysfunction (ED), female sexual disorders, andro- or menopause, and hypoactive sexual desire, are based on the symptom rather than the couple. This might be reductive and therapeutically dangerous.

Currently the commonly used definition for PE is the definition proposed by the International Society of Sexual Medicine, on the basis of which this condition is ‘characterised by ejaculation which always or nearly always occurs prior to or within about one minute of vaginal penetration, and the inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations, and negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy’ [15]. From these criteria, the key points characterising this pathological condition are the timing (measured as the intravaginal latency time, IELT), the feeling of loss of control over ejaculation, and the presence of distress within the couple [16]. The last aspect highlights that relational aspects are important in the pathogenesis of sexual dysfunction [17]. In this regard the female partner can be considered in the way as the man with the symptom. Both currently used adjectives (premature and rapid) refer to the partner’s sexual physiology and to the time course of the female sexual response, the ‘satisfaction factor’. Hence, PE could be considered as a partner-generated symptom.

The diagnosis of the couple with PE

The assessment of the psychological causes of PE includes extensive interviewing, with standardised psychological tests directed to both the patient and his partner, to establish the history of the dysfunction and the circumstances under which it occurs. Where medical results are normal, a diagnosis of psychogenic PE is considered likely. This ‘diagnosis by exclusion’ can lead to unreliable conclusions for various reasons: (i) it is impossible to show that a case of PE is generated by the mind (psychogenic); (ii) as stated above, all cases of PE have a psychological and/or relational aspect; and (iii), whilst research is increasing there is still a severe lack of knowledge on the central and peripheral ejaculation mechanisms. It can thus be inferred that in the near future there will be new tests capable of detecting new patients with organic PE.

During treatment the clinician should consider that marital problems are often involved. PE, like any sexual dysfunction, affects the intimacy of the couple. However, it is not easy to establish if the marital problems are the cause or the effect of PE. Thus, during the assessment, the sexologist should treat both the man and the woman, and investigate the actual time of the vaginal penetration; during coitus and penetration, the perceived time often differs from the actual time.

Although these considerations might suggest the importance of involving the partner in the treatment of PE, as highlighted in a review [3], the vast majority of men who present for treatment do not involve their partners. However, a recent study of the female sexual distress related to the partner’s PE [18] emphasised the great interest expressed by women in having a role in this male sexual symptom. In addition, some studies recommend [8,19,20], within the perspective of an integrated treatment, using semi-structured questionnaires to collect sexological and relational data. Interestingly, Limoncin et al. [18] proposed using a new diagnostic tool for detecting female sexual distress related to PE, the ‘FSDS-R-PE’.

Primary PE is considered when there are no other sexual dysfunctions, but in the presence of other sexual symptoms, such as ED or a lack of desire, the PE is assessed as secondary. In these cases it is fundamental to assess the sexuality with a specific history and with psychometric tools to evaluate desire and erectile function.

Moreover, PE is a common early manifestation of ED [21], or can occur with an unstable erection due to fluctuations in penile blood flow. In this case the man might ejaculate early to hide the weakness of the erection, and thus the PE responds successfully to the appropriate treatments for ED. All these possibilities should be considered when evaluating patients with PE.

Female sexual dysfunction (such as anorgasmia, hypoactive sexual desire, sexual aversion, sexual arousal disorders, and sexual pain disorders, as in vaginismus) are often present and might be secondary to the male PE, so that assessing female sexuality is an integral part of assessing PE.

In addition to a sexological evaluation, it is necessary that the clinician also conducts a physical examination; abnormal findings are unlikely to be associated with this condition. However, penile biothesiometry, and an evaluation of the prostate by TRUS with the standardised Meares and Stamey protocol [22], have been proposed as useful methods to evaluate and quantify penile sensitivity in PE [23].

Psychological therapies for PE

Behavioural therapies

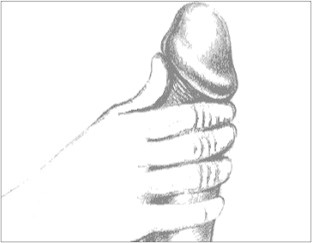

From the early 1900s until the 1990s, PE was considered as a psychological problem, and it was treated primarily with behavioural therapies, such as the ‘squeeze’ technique [14,24] and the ‘stop–start’ technique, introduced by Kaplan [25,26], based on the remarkable work of Semans [24]. Although Masters and Johnson suggested specifically curing PE using the ‘squeeze’ technique (Fig. 1), this approach carries some risk of discomfort. For this reason many sex therapists prefer the stop-start method.

Figure 1.

The squeeze technique to treat PE. When ejaculation seems inevitable, the man’s partner applies pressure, using the thumb of the first two fingers, just below the glans penis. This pressure should inhibit ejaculation and should be done several times before ejaculation is allowed. As a step in the learning of ejaculation control, the squeeze technique is generally no longer needed after therapeutic success.

Sexological therapy for PE starts from the approach that it is the couple, not the individual, that is dysfunctional. Sexual counselling can be of benefit for both idiopathic and organic causes of PE. Involving the partner in this process can dispel misperceptions about the symptom, decrease stress, enhance intimacy, and the ability to talk about sex and PE, and increase the chances of a successful outcome.

Counselling sessions are also helpful in uncovering conflicts in the relationship, psychiatric problems, and alcohol or drug misuse. For this reason, during treatment, the therapist can assign ‘sexual homework’, prescribing ‘sensate focus’, in which partners mutually stimulate nongenital body areas, which reduces the anxiety linked to coitus and the pressure on sexual performance [14,25]. In addition, the patients learn to: (i) evaluate preorgasmic pleasure; (ii) be aware of the ‘orgasmic point of no return’ (iii); prolong the plateau phase; and (iv) distinguish between excitation and orgasm (Table 1).

Table 1.

The components of behavioural therapy.

| Assessment | Educational components | Behavioural components |

|---|---|---|

| General history | Understanding of sexual anatomy | Sensate focus |

| Sexual history | Understanding of sexual physiology | Squeeze stop-start |

| Relationship history | Kegel’s exercises |

Sex therapy

With this term sexologists indicate many behavioural models of the short-term treatment of human sexual dysfunction [27]. The main aim of these therapies is to modify the dysfunctional behaviour, considering the role of personal history, past experiences, possible trauma, self-defeating attitudes and defences against sexual behaviour, the quality of the couple’s relationship, family education and religious beliefs. Common personality characteristics of men with PE are:

-

•

Insecure and anxious with aggressive and ‘castrating’ women;

-

•

Competitive, always demonstrating their virility;

-

•

Young and naïve at their first sexual experiences.

Generally, sex therapy methods for PE have good efficacy, and often allow the man to learn to recognise and respond to his PE. However, these treatments are not easy for the patient, and the man with PE must be actively involved in the therapy with his partner. In addition, follow-up data have shown that their efficacy tends to decrease over time [28].

Other therapies

The cognitive and informative strategies have been considered particularly useful for single men. The goal of this approach is to modify irrational thoughts and core beliefs inherent in the sexual life of both the patient and his partner, work together on reducing the performance anxiety, strengthen trust and confidence in the relationship between the marital partners, debunk male sexual mythology, improve sexual communication, enhance sexual knowledge, and teach sexual skills.

As PE can arise from ignorance, and sexual teaching is unfortunately largely absent in schools [29], bibliotherapy with simple and clear books [30], and the prescription of simple behaviours promoting an increase in the ejaculatory time, such as the prescription to ejaculate more frequently, to release the anal sphincter during intercourse, to favour the female-on top position, and possibly to use special condoms, might be a useful adjuvant treatment for PE.

Strengthening of the pubococcygeous muscles of the pelvic floor is a behavioural stage in sex therapy for PE. In these exercises, named after Arnold Kegel who devised them, the patient is trained to identify his pubococcygeous muscles during urination. He then clenches and releases these muscles with a few slow contractions of 2–3 s. As the muscles strengthen, the duration and number of slow contractions is gradually extended, together with fast contractions. A typical routine is:

-

•

Contract the pubococcygeous muscles for 5 s, release for 5 s, and repeat five times.

-

•

Contract the pubococcygeous muscles five times as fast as possible.

-

•

In the same session, repeat points 1 and 2.

-

•

Perform five sessions per day

In addition, a multivariate approach to treating PE, based on both ejaculatory latency and perceived control, has been proposed. The coital alignment technique is a couple-based therapy consisting of a basic physiological alignment that provides an effective stimulation for female coital orgasm [31]. This might be useful in couples with PE. The Reichian therapy for PE is based on the use of sensate rather than verbal communication with the patient. The therapist carefully chooses the environment and atmosphere, with patients and therapists on large cushions, using a friendly relationship on first-name terms, and involving non-erotic massages and role-playing. Hypnosis [32], mechanotherapy [33], re-educative and supportive therapies, and the extensive training programmes described elsewhere as alternatives to behavioural therapies, all suffer from considerable methodological weaknesses, a failure to specify subject and treatment variables, inadequate or non-existent control groups, a limited follow-up, and failure to obtain the partner’s validation of the patient’s progress [34].

Treatment programmes have also been designed for a group setting. The structured group treatment has been described in uncontrolled studies as a cost efficient and effective method to overcome PE [35], for both couples and single men [36]. The group treatment does not seem to provide and inferior outcome to the classic couple format [37].

Finally, the efficacy of a yoga-based protocol vs. treatment with fluoxetine has been evaluated for treating patients with PE [38]. In that study there was no significant difference between these therapeutic options. Thus, although other scientific evidence is necessary, it is possible that even yoga is useful for overcoming PE.

Medical therapies for the man or the couple

The efficacy of ‘talking therapies’ in the management of PE is not supported by convincing data from controlled clinical studies. For this reason, pharmacological treatment is now receiving increased attention from both medical sexologists and the pharmaceutical industry. Whilst behavioural therapies in their original format require a couple, medical treatments can be used by the man alone. However, counselling with the couple is also suitable.

Systemic and local drugs

Drugs that are widely prescribed for PE therapy are antidepressants (specifically those increasing serotonin levels, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and α-adrenergic blockers. The serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants [39–41] have an effect by increasing the penile threshold. In addition, these drugs do not change the amplitude and latency of the sacral evoked response and cortical somatosensory evoked potential. The most important drug in the clinical practice is dapoxetine. Reports suggest that dapoxetine 60 mg significantly improves the control of the ejaculation reflex, providing an IELT of >3 min. It thus represents the first-line officially approved pharmacotherapy for PE [12].

Another drug class used for treating PE is the phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor (sildenafil, tadalafil and vardenafil), usually the first choice for treating ED but that has also been used alone or combined with serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a treatment for PE [11,42]. In addition, for patients with ED and PE, treatment with intracavernous medications, rather than sildenafil alone or combined with paroxetine [43,44] is recommended. Indeed, in some cases PE and ED are comorbid symptoms. Topical agents such as anaesthetics and herbal products are also used, with limited efficacy [45].

In patients with prostate inflammation and PE, the specific therapy for chronic prostatitis has been suggested. Furthermore, a recent study reported that a metered-dose aerosol spray containing a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (TEMPE, Plethora Solutions, London, UK) produced a 2.4-fold increase in baseline IELT and significant improvements in ejaculatory control, and in the sexual quality of life of both patient and partner [11]. Finally, an interesting possibility is the role of acupuncture in the medical care of PE, but other investigations are necessary [46].

Follow-up and critical evaluation of medical therapies

Current methods and measures used to assess the outcomes of treating PE are only standardised with some difficulty. Antidepressant drugs are generally effective in restoring ejaculatory control. However, as these drugs may significantly worsen ED, they are strongly contraindicated for patients with both PE and ED [47].

Whilst the pharmacological treatment of PE, e.g. with dapoxetine, has been shown to be reliable and effective, its effect is often localized to the period of drug consumption.

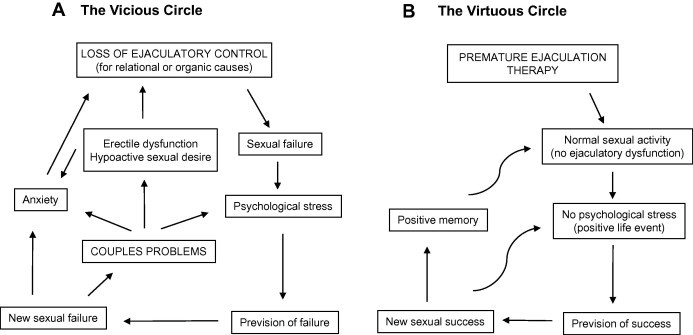

The evidence that dapoxetine, as well as other antidepressants, is a symptomatic therapy, is that patients taking dapoxetine and obtaining good ejaculatory control can still have PE when the pharmacotherapy stops. The treatment of PE is more efficient when drugs are prescribed up to a maximum of 60 days, in association with sexual therapy, where the partner is also involved. Therefore, whilst drugs postpone the emission phase, the patient can focus attention on the body’s sensations preceding ejaculation. In doing so the patient learns to control ejaculation and, creating a ‘positive memory’ of sexual success, also increases his self-esteem (Fig. 2, panel B).

Figure 2.

The pathophysiology of PE. Stress from sexual failure and subsequent anxiety have a positive feedback during PE (Panel A). Pharmacological and/or psychological therapies destroy this vicious circle, transforming it into a virtuous circle (Panel B). Note that during the vicious circle, other couple’s pathologies can arise.

In fact, a negative intervening factor in the sexual dysfunction is the vicious circle caused by ‘sexual failure’. Pharmacotherapy avoids the patient entering this vicious circle (Fig. 2, panel A). This effect can be obtained both with an effective treatment by psychotherapy and with an effective (and safe) treatment with dapoxetine.

Conclusion

As psychoanalysis in sexology aims to recognise the deep subconscious that might have caused the psychological disease [48], the approach suggests an aetiological therapy. However, although Freudian theory might successfully explain subconscious conflicts leading to sexological pathologies, the evidence highlights its many limits in resolving sexual difficulties. An approach directed to the treatment of symptoms, rather than to the causes of the disease, was developed in the 1960s. The two pioneers of this approach, Masters and Johnson, devised a new sex therapy on the basis of the behavioural approach, which could be considered a ‘Copernican’ revolution in the world of psycho-sexology. Masters and Johnson’s sex therapy was new also because of its principle of adopting an integrated (pharmacological and psychological) model to treat sexual dysfunction. The aim of the sexologist is to identify which causal predominates in a specific patient, and design the therapy on this basis. It is also necessary to consider, in addition to pharmacotherapy, the couple’s dynamics, to provide specific sexual counselling. This treatment can be successful only if the therapy is structured accordingly, with behavioural approaches and with the sex therapist [49]. Therefore, during the assessment is necessary to provide a combination of psychological and pharmacological therapy to minimise the chance of relapse [19].

Finally, considering the importance of sexual counselling in the therapy of PE and the role of prostate diseases in their pathogenesis, a prevention policy should focus on both the sexual and andrological education of young and adult males. This form of information and education is absent in many countries. The political institutions should promote information campaigns to prevent andrological and sexological diseases in males and in the couple.

In conclusion, aetiological therapies must be used wherever possible and treatment should involve the partner, to improve the couple’s compliance and the effectiveness of long-term recovery. Behavioural approaches and pharmacological agents are both symptomatic therapies, the goal of which is to delay the ejaculation, and they do not consider the underlying causes of the sexual dysfunction. Because of the deep psychological effect that PE can have on patients, the physician must always take the sexological approach into account [47].

Integrated medical and psycho-sexological sex therapy (‘Shared Care’ [50]) requires a mutual understanding and respect for the different disciplines involved in sexology. This approach will further increase the therapeutic potency of effective and safe treatments such as dapoxetine. In this aspect, the roles of two sexual experts, i.e. the physician and the psychologist, are very important, as they can improve the biological, psychological and relational factors in a sexual dysfunction such as PE.

Conflict of interest

Professor Jannini is speaker and consultant of Janseen, Bayer, Lilly, Pfizer and Menarini. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Source of funding

Italian Ministry of University (MIUR-PRIN and FIRB grants).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

Appendix A.

A.1. Search strategy

Data were gathered from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed website inserting the following key-words: “psychological treatment AND premature ejaculation”, “pharmacotherapy AND premature ejaculation”, “couple AND premature ejaculation”, “integrated treatment AND premature ejaculation”, “yoga AND premature ejaculation”, “acupuncture AND premature ejaculation”, “Dapoxetine”, and “coital alignment technique”. Additional articles were extracted based on recommendations from an expert panel of authors.

References

- 1.Jannini E.A., Simonelli C., Lenzi A. Disorders of ejaculation. J Endocrinol Invest. 2002;25:1006–1019. doi: 10.1007/BF03344077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jannini E.A., Simonelli C., Lenzi A. Sexological approach to ejaculatory dysfunction. Int J Androl. 2002;25:317–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2002.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graziottin A., Althof S. What does premature ejaculation mean to the man, the woman, and the couple? J Sex Med. 2011;8(Suppl. 4):304–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham K. Über ejaculatio praecox. Zeitschr Aerztl Psychoanal. 1917;4:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinsey A., Pomeroy W.B., Martin C.E., editors. Sexual behavior in the human male. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro B. Premature ejaculation: a review of 1130 cases. J Urol. 1943;50:374–377. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waldinger M.D. The neurobiological approach to premature ejaculation. J Urol. 2002;168:2359–2367. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Althof S.E., Abdo C.H., Dean J., Hackett G., McCabe M., McMahon C.G. International society for sexual medicine’s guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2947–2969. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachs B.D. The false organic-psychogenic distinction and related problems in the classification of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impotence Res. 2003;15:72–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kandeel F.R., Koussa V.K., Swerdloff R.S. Male sexual function and its disorders: physiology, pathophysiology, clinical investigation, and treatment. Endocrine Rev. 2001;22:342–388. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.3.0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowland D., McMahon C.G., Abdo C., Chen J., Jannini E., Waldinger M.D. Disorders of orgasm and ejaculation in men. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1668–1686. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porst H.An. Overview of pharmacotherapy in premature ejaculation. J Sex Med. 2011;8(Suppl. 4):335–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heaton J.P. Central neuropharmacological agents and mechanisms in erectile dysfunction: the role of dopamine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:561–569. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masters W., Johnson V.E. Little Brown; Boston: 1970. Human sexual inadequacy. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMahon C.G., Althof S.E., Waldinger M.D., Porst H., Dean J., Sharlip I.D. An evidence-based definition of lifelong premature ejaculation: report of the international society for sexual medicine (ISSM) ad hoc committee for the definition of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1590–1606. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jannini E.A., Lenzi A. Ejaculatory disorders: epidemiology and current approaches to definition, classification and subtyping. World J Urol. 2005;23:68–75. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen R.C., McMahon C.G., Niederberger C., Broderick G.A., Jamieson C., Gagnon D.D. Correlates to the clinical diagnosis of premature ejaculation: results from a large observational study of men and their partners. J Urol. 2007;177:1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limoncin E., Tomassetti M., Gravina G.L., Ciocca G., Carosa E., DiSante S. Premature ejaculation results in female sexual distress: standardization and validation of a new diagnostic tool for sexual distress, the FSDS-R-PE. J Urol. 2013;189:1830–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perelman M.A. A new combination treatment for premature ejaculation: a sex therapist’s perspective. J Sex Med. 2006;3:1004–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jannini E.A., Lenzi A. Evaluation of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med. 2011;7:328–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lotti F., Corona G., Rastrelli G., Forti G., Jannini E.A., Maggi M. Clinical correlates of erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation in men with couple infertility. J Sex Med. 2012;8:2698–2707. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meares E.M. Bacteriologic localization patterns in bacterial prostatitis and urethritis. Invest Urol. 1968;5:492–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xin Z.C., Chung W.S., Choi Y.D., Seong D.H., Choi Y.J., Choi H.K. Penile sensitivity in patients with primary premature ejaculation. J Urol. 1996;156:979–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semans J. Premature ejaculation: a new approach. Southern Med J. 1955;49:353–358. doi: 10.1097/00007611-195604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan H. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1974. The new sex therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan H. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1989. How to overcome premature ejaculation. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walen S., Hauserman N.M., Lavin P.J. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1977. Clinical guide to behavior therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metz M.E., McCarthy B.W. New Harbinger Publications; Oakland, CA: 2003. Coping with premature ejaculation: overcome PE, please your partner, and have great sex. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinchera A.J.E., Lenzi A. Research and academic education in medical sexology. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26(Suppl. 3):13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kingsberg S., Althof S.E., Leiblum S. Books helpful to patients with sexual and marital problems. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:219–228. doi: 10.1080/009262302760328262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce A.P. The coital alignment technique (CAT): an overview of studies. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:257–268. doi: 10.1080/00926230050084650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Austin V. Thorsons; San Francisco: 1996. Hypnosex. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dengrove E. The mechanotherapy of sexual disorders. Sex Res. 1971;7:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilmann P.R., Auerbach R. Treatments of premature ejaculation and psychogenic impotence: a critical review of the literature. Arch Sexual Behav. 1979;8:81–100. doi: 10.1007/BF01541215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price S., Heinrich A.G., Golden J.S. Structured group treatment of couples experiencing sexual dysfunctions. J Sex Marital Ther. 1980;6:247–257. doi: 10.1080/00926238008406090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeiss H.A., Levine A.G. Treatment for premature ejaculation through male-only groups. J Sex Marital Ther. 1978;4:139–143. doi: 10.1080/00926237808403013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golden J.S., Price S., Heinrich A.G., Lobitz W.C. Group vs. couple treatment for sexual dysfunctions. Arch Sex Behav. 1978;7:593–602. doi: 10.1007/BF01541925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhikav V., Karmarkar G., Gupta M., Anand K.S. Yoga in premature ejaculation: a comparative trial with fluoxetine. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1726–1732. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waldinger M.D., Hengeveld M.W., Zwinderman A.H. Paroxetine treatment of premature ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1377–1379. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.9.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kara H., Aydin S., Yucel M., Agargun M.Y., Odabas O., Yilmaz Y. The efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of premature ejaculation: a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Urol. 1996;156:1631–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S.C., Seo K.K. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine, sertraline and clomipramine in patients with premature ejaculation: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 1998;159:425–427. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)63940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jannini E.A., McMahon C., Chen J., Aversa A., Perelman M. The controversial role of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in the treatment of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med. 2011;8:2135–2143. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen J., Mabjeesh N.J., Matzkin H., Greenstein A. Efficacy of sildenafil as adjuvant therapy to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in alleviating premature ejaculation. Urology. 2003;61:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salonia A., Maga T., Colombo R., Scattoni V., Briganti A., Cestari A. A prospective study comparing paroxetine alone versus paroxetine plus sildenafil in patients with premature ejaculation. J Urol. 2002;168:2486–2489. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morales A. Developmental status of topical therapies for erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction. Int J Impotence Res. 2000;12(Suppl. 4):S80–S85. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jannini E.A., Lenzi A. Sexual dysfunction: is acupuncture a therapeutic option for premature ejaculation? Nature Rev Urol. 2011;8:235–236. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leiblum S., Rosen R.C., editors. Principles and practice of sex therapy. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hartmann U. Sigmund Freud and his impact on our understanding of male sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2332–2339. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Althof S.E. What’s new in sex therapy (CME) J Sex Med. 2010;7:5–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barnes T. Integrated sex therapy: the interplay of behavioral, cognitive and medical approaches. In: Carson C.C., Kirby E.S., Goldestein I., editors. Textbook of erectile dysfunction. Media IM; Oxford: 1999. pp. 465–484. [Google Scholar]