Abstract

Introduction

Of women aged >40 years, 6% have voiding dysfunction (VD), but the definition for VD in women with respect to detrusor underactivity (DU) and bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is not yet clear. In this review we address the current literature to define the diagnosis and treatment of VD more accurately.

Methods

We used the PubMed database (1975–2012) and searched for original English-language studies using the keywords ‘female voiding dysfunction’, ‘detrusor underactivity’, ‘acontractile detrusor’ and ‘bladder outlet obstruction and urinary retention in women’. We sought studies including the prevalence, aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of female VD.

Results

In all, 20 original studies were identified using the selected search criteria, and another 45 were extracted from the reference lists of the original papers. All studies were selected according to their relevance to the current topic and the most pertinent reports were incorporated into this review.

Conclusion

Female VD might be related to DU or/and BOO. Voiding and storage symptoms can coexist, making the diagnosis challenging, with the need for a targeted clinical investigation, and further evaluation by imaging and urodynamics. To date there is no universally accepted precise diagnostic criterion to diagnose and quantify DU and BOO in women. For therapy, a complete cure might not be possible for patients with VD, therefore relieving the symptoms and minimising the long-term complications associated with it should be the goal. Treatment options are numerous and must be applied primarily according to the underlying pathophysiology, but also considering disease-specific considerations and the abilities and needs of the individual patient. The treatment options range from behavioural therapy, intermittent (self-)catheterisation, and electrical neuromodulation and neurostimulation, and up to urinary diversion in rare cases.

Abbreviations: VD, voiding dysfunction; DU, detrusor underactivity; DO, detrusor overactivity; DM, diabetes mellitus; PVR, postvoid residual urine volume; Qmax, maximum urinary flow rate; Pdet, detrusor pressure; Pdetmax, maximum Pdet; PdetQmax, Pdet at Qmax; ApBO, acute prolonged bladder overdistension; POP, pelvic organ prolapse; MUS, mid-urethral sling; TVT, tension-free vaginal tape; DV, dysfunctional voiding; DSD, detrusor sphincter dyssynergia; PFM, pelvic floor muscles; US, ultrasonography; PFS, pressure-flow study; EMG, electromyography; VCUG, voiding cysto-urethrogram; IVES, intravesical electrical stimulation; CIC, clean intermittent self-catheterisation; SNM, sacral neuromodulation; BTA, botulinum toxin A

Keywords: PVR measurement, Bladder diary, Uroflowmetry, Women

Introduction

Voiding dysfunction (VD) in women is a common health problem and can be related to either an abnormality in detrusor muscle activity and/or BOO. In a large cross-sectional Internet survey including 15,861 women aged >40 years in the USA, UK and Sweden, terminal dribbling was the most common symptom in 38.3%, followed by a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying in 27.4% and a weak stream in 20.1% [1]. In the standardisation of terminology of LUTS there is a lack of consensus about a precise diagnosis and definition of voiding abnormalities. Storage and voiding symptoms can coexist, which might have an independent pathophysiology or be related to one another [2]. This makes female VD a challenge in clinical practice, to obtain the precise diagnosis and choose the best and most suitable treatment.

In this review we address what is considered as VD in females, identify the causes, and suggest possible diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Methods

We used the PubMed database (1975–2012) and searched for original English-language studies using the keywords ‘female voiding dysfunction’, ‘detrusor underactivity’, ‘acontractile detrusor’, ‘urinary retention’ and ‘bladder outlet obstruction’ in women. In all, 20 original studies were identified using the selected search criteria, and a further 44 were extracted from the reference lists of the original papers. We assessed studies concerned with the prevalence, aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of female VD. The most pertinent 65 reports are the basis for this article.

Aetiology of female VD

VD is used to describe a clinical condition that affects bladder emptying. The causes can be related to either detrusor underactivity (DU) or acontractility, and/or BOO (Table 1).

Table 1.

The causes of female VD.

| Condition | Type | Detail |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Abnormal detrusor activity (underactive/acontractile) | Neurogenic | Cerebral: |

| Cerebrovascular stroke | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | ||

| Multiple system atrophy | ||

| Hydrocephalus | ||

| Tumour (brain, spinal cord) | ||

| Spinal (sacral): | ||

| Spinal cord injury | ||

| Disc herniation | ||

| Transverse myelitis | ||

| Spina bifida | ||

| Subsacral (peripheral): | ||

| Pelvic nerve injury (iatrogenic – traumatic) | ||

| Myogenic | Ageing | |

| ApBO | ||

| Mixed | DM | |

| Other risk factors | Menopause | |

| Immobility | ||

| Recurrent UTI | ||

| Anaesthesia | ||

| Post operative | ||

| Drugs | ||

| Psychological | ||

| (2) BOO | Anatomical | Iatrogenic obstruction: |

| Anti-incontinence (sling) procedures | ||

| Urethral procedures | ||

| POP | ||

| Anterior vaginal wall prolapse | ||

| Apical prolapse (procedentia) | ||

| Inflammatory process: | ||

| Inflammation of urethra | ||

| Urethral stricture | ||

| Urethral diverticulum | ||

| Miscellaneous: | ||

| Bladder calculi/tumour | ||

| Retroverted uterus | ||

| Female genital tumours | ||

| Functional | Dysfunctional voiding | |

| DSD | ||

| Fowler’s syndrome | ||

Abnormal detrusor muscle activity

The ICS defines DU as ‘a contraction of reduced strength and/or duration, resulting in prolonged bladder emptying and/or failure to achieve complete bladder emptying within a normal time span’, while an acontractile detrusor is defined as one ‘which cannot be demonstrated to contract during urodynamic studies’ [3].

‘Primary’ or ‘idiopathic’ DU is thought to be an age-related decrease in detrusor contractility with no other causes, while secondary DU is associated with a detectable relevant condition, e.g., diabetes mellitus (DM) or BOO [4]. The pathogenesis of DU can be myogenic or neurogenic.

Neurogenic factors

Cerebral (especially pontine), spinal sacral and subsacral lesions can cause DU or acontractile detrusor (Table 1). The patient’s symptoms and urodynamic presentations vary according to the location and extension of the lesion, and might change during disease progression, e.g., in the early stages of multiple sclerosis, overactive bladder symptoms are common, but in late stages chronic voiding problems prevail. The prevalence of DU in multiple sclerosis is 0–40%, and 25% in the earlier stage. Later in the disease 25% of patients had chronic urinary retention with an increased postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) due to detrusor weakness and/or functional BOO [5].

Impaired detrusor contractility is very frequent in patients with multiple system atrophy. It is present in 58% of patients within the first 4 years and in 76% during the course of the disease [6], often combined with detrusor overactivity (DO), leading clinically to an increased PVR, urgency and urgency incontinence. The urological symptoms can be the first sign of the disease.

In stroke patients, DU was found in up to 40% [7]. It appears to be more common in patients with pontine strokes rather than in those with fronto-parieto-temporal lesions.

DU can result from iatrogenic nerve damage after radical pelvic surgery, due to peripheral, mostly partial, sympathetic and parasympathetic denervation. More than half of women with a normal urinary tract function before surgery have voiding problems after a radical hysterectomy, at least temporarily, using either abdominal straining or needing catheterisation [8]. VD occurs in a third of patients treated for rectal cancer, with a higher risk in low rectal cancer and abdominoperineal resection [9].

Myogenic factors

The ageing process is a common but not the only reason for detrusor weakness. It can cause degenerative detrusor weakness, and affect the detrusor’s ability to maintain a sustained contraction to empty the bladder completely. However, the results are not uniform. In a study of men and women aged >70 years, impaired detrusor contractility was detected in 48% of men and 12% of women [10]. Madersbacher et al. [11] studied the urodynamic changes with ageing in women and showed a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), voided volume, bladder capacity, maximum urethral closing pressure, functional urethral length and an increased PVR, but there were no significant age-associated changes for maximum detrusor pressure (Pdetmax), detrusor pressure at Qmax (PdetQmax), and incidence of DO. Resnick and Yalla [12] found, among institutionalised elderly people with urinary incontinence, that 33% had DO with an impaired contractile function.

Acute prolonged bladder overdistension (ApBO) is an important, but often unrecognised medical phenomenon and occurs after extensive pelvic surgery, operations with spinal anaesthesia and prolonged childbirth. Silent postpartum urinary retention affects 37% of women, with a PVR of >150 mL [13]. The pathogenesis of ApBO probably comprises two consecutive stages, i.e., a primary temporary neurogenic dysfunction leading to acute urinary retention, that if neglected will be followed by secondary myogenic detrusor damage. Recovery depends on whether there is reversible or irreversible damage [14].

Mixed (neurogenic and myogenic) factors

A good example of this is ‘diabetic cystopathy’, a term first introduced by Frimodt-Moller [15], to describe LUTS associated with DM. An abnormal bladder function with DM is traditionally attributed to peripheral autonomic neuropathy leading to impaired sensation, with consequent bladder overdistension, decreased flow rates and an increased PVR. However, detrusor smooth muscle cells can also be modulated directly by hyperglycaemia, which induces oxidative stress in muscle cells, with macro- and micovascular damage. The latter might have a similar effect on the diabetic bladder as defects seen with retinopathy and nephropathy [16]. Lee et al. [17] reported the early urodynamic findings of diabetic bladder dysfunction in women; there was DU in 34.9%, DO in 14% and BOO in 12.8%, but BOO was due to a comorbidity of other origin.

Other risk factors

Other risk factors can also contribute to DU, e.g., menopause [18], constipation [19], immobility, anaesthesia, and recurrent UTI. Menopause can result in axonal degeneration and loss of detrusor muscle cells, while constipation leads to rectal distension, reflexively decreasing detrusor contractility and/or obstructing the bladder outlet due to faecal impaction.

A broad range of medication is known to contribute or to cause VD, e.g., antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antidepressants, some antiparkinsonian drugs (apomorphine), opiates, antihistamines and adrenergic agonists.

Boo

The causal factors for female BOO are either anatomical or functional (Table 1).

Anatomical

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP), such as a high-grade cystocele or uterine prolapse, can lead to ‘mechanical’ BOO. This occurs in 2% of women with grades 1 and 2 POP, and up to 33% with grades 3 and 4 POP [20]. A cystocele can cause kinking of the urethra, and moreover, a large amount of the energy created by detrusor contraction is lost due to inadequate pressure transmission from the bladder to the urethra.

De novo VD has been reported after placing mid-urethral slings (MUS). The reported rate after placing a tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) is 3–15% [21]. The transobturator tape was associated with similar rates of VD as the TVT, with a significant decrease in Qmax from 30 to 20 mL/s (P = 0.001) and a significant increase in PVR from 13 to 43 mL (P = 0.03) [22].

Urethral strictures can result from urethral inflammation, traumatic urethral injury or iatrogenic trauma due to recurrent urethrotomies or long-term catheterisation.

Functional

Causes for functional BOO are dysfunctional voiding (DV) and detrusor sphincter dyssynergia (DSD). Other rare causes include Fowler’s syndrome and a primary bladder neck obstruction.

The ICS [3] defined DV as ‘an involuntary intermittent contraction of the peri-ureteral striated muscle during voiding in neurologically intact individuals’, a phenomenon first described by Hinman [23], while DSD is defined as ‘a detrusor contraction concurrent with an involuntary contraction of the striated urethral sphincter/pelvic floor muscle in neurogenic patients’.

Hinman syndrome (a non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder) is also termed an ‘acquired voiding dysfunction’. Hinman suggested that this VD is caused by faulty learned behaviour as patients attempt to inhibit micturition by voluntary contraction of the external urethral sphincter/pelvic floor muscles (PFM), which can be reversed with re-educational therapy.

Fowler and Kirby [24] described the electrophysiological responses of the urethral rhabdosphincter in young women with unexplained urinary retention, using a needle electrode, and reported abnormal electromyographic activity (complex repetitive discharges and decelerating bursts). The typical clinical presentation of Fowler’s syndrome is a young female patient presenting with painless urinary retention (PVR > 1 L), pain during catheter withdrawal and no evidence of urological or neurological disease. Investigations showed an abnormally high urethral pressure profile and an increased sphincter volume on ultrasonography (US). Up to 40% of these patients have polycystic ovary disease, with the hypothesis that a hormonal abnormality might affect sphincter activity.

The diagnosis of female VD

In women with VD, the voiding and storage symptoms can coexist, making the diagnosis even more challenging. Thus they must be accurately evaluated with urodynamic and imaging studies, to obtain a precise diagnosis.

Symptoms and signs

VD symptoms include hesitancy, weak stream, intermittency, straining to void, spraying or a split stream, incomplete bladder emptying, a need to immediately re-void, position-dependent micturition and postmicturition dribbling. Sometimes women complain of concomitant stress and/or urge urinary incontinence. Storage-related symptoms such as frequency, urgency and nocturia might be present, either due to an increased PVR or associated comorbidity [2].

Urinary retention, painless or painful, and acute or chronic, might be present. In acute retention, patients are unable to pass urine and on examination have a palpable or percussible bladder. Chronic retention has a more insidious presentation and patients complain of frequency, weak stream, overflow incontinence or recurrent UTI.

In females with VD the predictive value of voiding symptoms is rather low, e.g., for the PVR the sensitivity is 13–57%, and the specificity 18–38% [25,26]. Kuo [27] concluded that clinical symptoms alone are not reliable in the differential diagnosis of LUTS in women. Thus it is very important for physicians to know that the diagnosis of female VD depends both on the patient’s symptoms and the final investigational results, including a urodynamic study.

Physical examination

Suprapubic fullness can be present during an abdominal examination. A pelvic examination can show vaginal atrophy, vulvo-vaginitis, POP or pelvic masses. Palpation of the urethra and anterior vaginal wall can detect urethral tenderness, a diverticulum or scarring. A DRE can be used to diagnose faecal impaction, assess the anal sphincter tone and the ability to contract voluntarily the anal sphincter. The spinal reflex activity of L5–S5 is assessed by testing the bulbocavernosus reflex (squeezing of the clitoris induces anal sphincter contraction), and the spinal reflex activity of the S4–S5 nerve roots by anal reflex testing.

Urine analysis and urine culture

UTI in women has been reported to be associated with VD; up to 42% of female patients with VD had a history of recurrent UTI [28].

US can be used to estimate the PVR, bladder wall thickness, and to identify any associated pathologies, e.g., bladder stone or diverticulum [29].

Non-invasive urodynamic testing

A bladder diary recorded for 2 days [30] or 3–7 days [31] provides objective data on fluid intake, the frequency of micturition, total voided volume, maximum voided volumes and incontinence episodes.

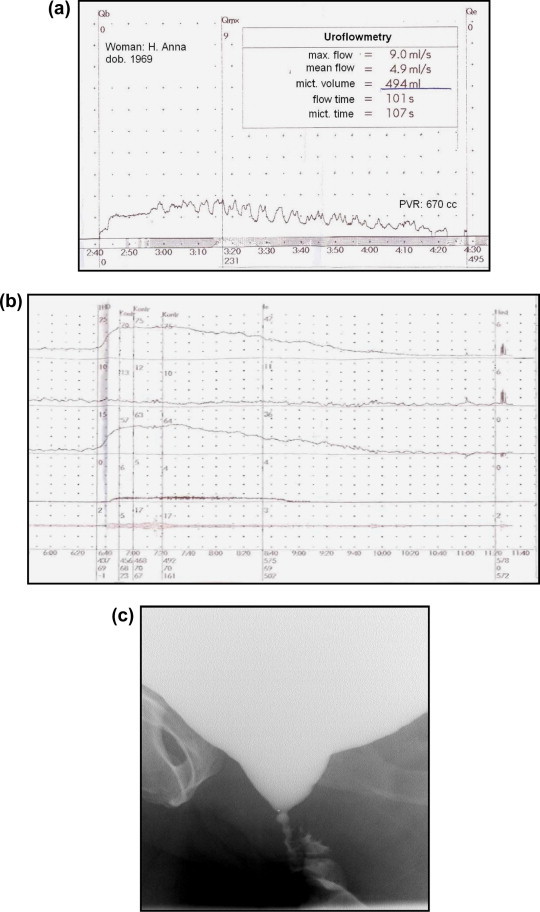

Uroflowmetry shows a prolonged and either continuous, fluctuating or interrupted pattern with no peak (plateau pattern) with a decreased maximum and mean flow rate (Fig. 1). However, uroflowmetry alone cannot distinguish between DU and BOO, so pressure-flow studies (PFS) are necessary [32].

Figure 1.

Results from a 44-year-old woman who underwent several urethrotomies and urethroplasty, and presented with severe voiding symptoms and a high PVR: (a) Uroflowmetry showed a prolonged fluctuating pattern with a decreased Qmax and a PVR of 670 mL. (b) The PFS showed a high PdetQmax of 64 cm H2O and a low Qmax of 4 mL/s. (c) VCUG showed a closed bladder neck due to functional and anatomical reasons.

The PVR can be estimated using US or catheterisation. According to Abrams et al. [32], VD in women is associated with a PVR of >30% of the functional bladder capacity.

Invasive urodynamic studies

If noninvasive urodynamic testing detects abnormalities, to distinguish between DU and BOO, invasive urodynamic tests, especially PFS, are necessary. Urodynamic studies can be combined with video-cystography (video-urodynamics) and electromyography (EMG) of the PFM/striated sphincter.

Urodynamic challenges in the diagnosis of female VD

There is no universally accepted precise diagnostic criterion to diagnose and quantify DU and/or BOO in women [2]. Algorithms, which have been developed to quantify detrusor power during voiding, like the Griffiths Watt factor [33], Schafer’s nomogram [34] and bladder contractility index [35] are validated for adult men but not for women [4]. There is only one validated nomogram for women, the Blavais–Groutz nomogram [36], but it does not reflect all findings about BOO and detrusor contractility. Moreover, in several other studies the urodynamic criteria were evaluated for BOO in women. The values of both Qmax (mL/s) and PdetQmax (cm H2O) were different, with mean or mean (SD) values of PdetQmax of ⩾35 [37], 37.2 (19.2) [36], 42.8 (22.8) [38] and ⩾60 [39] reported, with relevant values of Qmax of ⩽15 [37], 9.4 (3.9) [36], 9 (6.2) [38] and ⩽15 [39], respectively. Taking these different values into account we suggest that a PdetQmax of ⩾40 cm H2O and a Qmax of ⩽15 mL/s are indicative of BOO (Fig. 1).

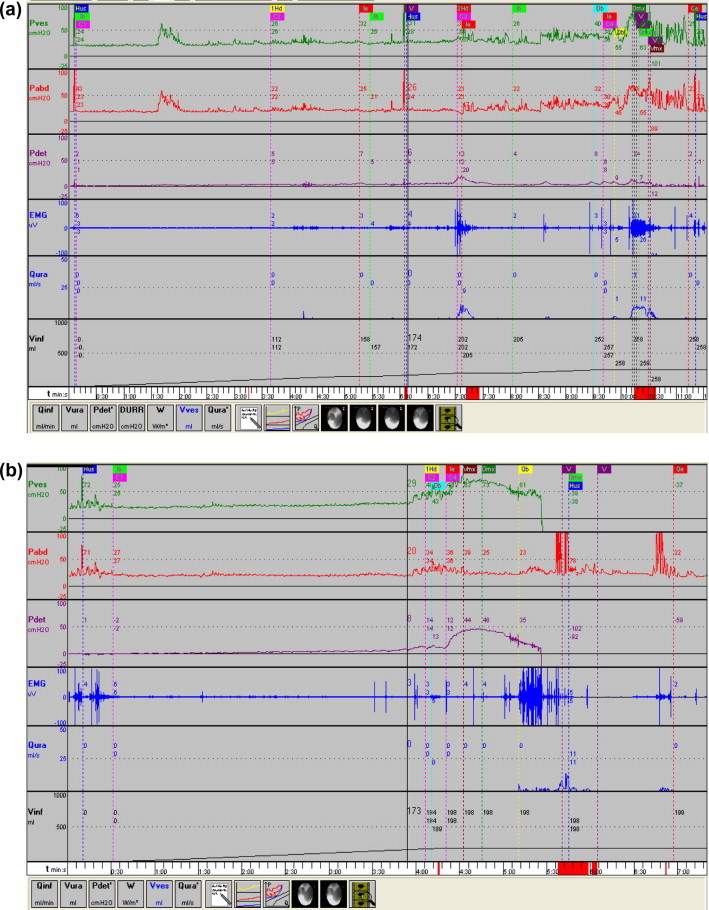

The diagnosis of DU is often difficult in women as they void at a very low detrusor pressure (Pdet). This could be because they have a low urethral resistance due to perfect relaxation of the PFM and/or due to a weak bladder outlet. With this situation there is no need for the detrusor to accumulate relevant pressures [35]. Some women showed no appreciable increase in Pdet during voiding and accordingly no diagnosis of DU could be made. However, when the bladder neck is blocked by balloon inflation of the urodynamic catheter and voiding is repeated, then the Pdet might increase considerably, indicating that the detrusor is capable of producing a pressure, and the main cause of a low Pdet in routine PFS is the absence of urethral resistance. This can also be shown in some women when they are asked to interrupt the stream during voiding, but this is not always possible due to sphincter weakness. Therefore this test is less reliable than bladder neck blocking (Fig. 2). The finding of a forceful detrusor contraction with a blocked bladder neck has prognostic value. When implanting a sling the risk of postoperative voiding difficulties is much lower when an adequate detrusor contraction is present.

Figure 2.

A urodynamic study of a 91-year-old woman with mixed urgency and stress continence. (a) The urodynamic curves show DO with weak detrusor contractions, accompanied by increased EMG activity (she tries to hold on voluntarily when urgency occurs), at maximum cystometric bladder capacity only a minor increase of detrusor pressure, and voiding by abdominal straining. (b) On blocking the bladder neck with the inflated balloon of the urodynamic catheter, there is a good detrusor contraction with a detrusor pressure amplitude of 50 cm H2O, indicating that with increased outlet resistance (e.g. after sling implantation), a detrusor contraction can occur.

Despite all these studies there is still no agreement and a lack of consensus on the precise determination and definition of female VD based on urodynamic variables.

The voiding cysto-urethrogram (VCUG)

The VCUG provides important information about the morphology and function of the lower urinary tract and is essential for locating an infravesical obstruction. It can be done either alone (Fig. 1) or combined with urodynamics (VUD).

EMG of the PFM and the striated sphincter

Mostly, EMG of the PFM is recorded using self-adhesive electrodes. Increased activity of the PFM during voiding or nonrelaxation can be documented with EMG, which can be combined with PFS (PFS–EMG). This gives additional information and is useful to differentiate between a functional and structural obstruction.

Endoscopy

Cysto-urethroscopy, including calibration of the meatus and urethra, gives additional information about the cause of BOO and the consequences of infravesical obstruction. However, bladder wall trabeculation is not necessarily a sign of infravesical obstruction. Trabeculation not related to BOO related can occur with infection, DO and chronic overdistension.

The treatment of female VD

Different therapeutic options are available to treat female VD, depending on the final diagnosis and whether the target is the detrusor, the bladder outlet or both.

Prevention and care after surgery

The early recognition of urinary retention after major surgery and labour might avoid the long-term problems associated with ApBO. This emphasises the importance of strict postoperative voiding surveillance, with measurements of PVR using US, and just to assess voiding volumes without an estimate of PVR is not sufficient.

Nerve-sparing techniques for radical pelvic surgery, preserving the pelvic autonomic nerves, are more favourable in terms of an early return of bladder function [40,41].

Treatment of DU

The treatment of women with DU should target either increasing bladder contractility, decreasing outflow resistance, or both [4]. There are several treatment options available.

Behavioural therapy

Women with DU should first be offered behavioural therapy, comprising lifestyle modifications and bladder training, especially voiding at regular intervals to avoid bladder overdistension. Constantinou et al. [42] presented the concept of ‘optimum filling volume for minimum bladder work’ and showed that with an adequate bladder filling volume of 300–350 mL the detrusor contraction is most effective. Assisted voiding by abdominal straining is an option for women who are able to relax their PFM while straining to void. With double- and triple-voiding, about 20 min after micturition the patient should try again to empty the bladder, so the PVR can be reduced gradually.

Pharmacotherapy

Drug treatment for VD mostly includes muscarinic receptor agonists (e.g. bethanechol) or cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g. distigmine). However, there are no studies confirming that parasympathicomimetics are able to induce or reinforce detrusor contractions [43]. Nevertheless, they might have the clinical effect that the sensation of bladder fullness is recognised earlier by increasing the muscle tone of the bladder, and are therefore a benefit for some patients.

Another target is to decrease outflow resistance using α-blockers, which can facilitate voiding but have the danger of inducing or increasing stress urinary incontinence.

Intravesical electrical stimulation (IVES)

IVES can be used to improve bladder dysfunction by stimulating A-δ mechanoreceptor afferents. To be effective IVES should be applied only if at least some functioning afferent fibres between the bladder and the cortex are still intact, and the detrusor muscle can still contract [44]. IVES proved to have a role in detrusor reinforcement in ApBO; up to two-thirds of patients with a weak detrusor regained balanced voiding [45]. Of patients with incomplete spinal cord injury and who had chronic neurogenic non-obstructive urinary retention, 37.2% responded to IVES and 83.3% experienced again the sensation of bladder filling [46].

Clean intermittent self-catheterisation (CIC)

If there is a significant PVR that cannot be abolished or lowered otherwise, CIC is indicated. This should be timed to every 4–5 h, encouraging the patient to use abdominal Valsalva and positional techniques to empty the bladder completely while the catheter is in the bladder. Others prefer the CIC frequency to depend on the voided volume and PVR, with both together not >600 mL. CIC is still the standard treatment of choice for DU and is also suitable for long-term care [47]. Indwelling catheterisation is a last resort for women with VD in whom all other treatments have failed or who are unable to use CIC regularly, with a preference for a suprapubic over a urethral catheter, as there is a lower incidence of contamination. CIC and especially indwelling catheterisation can compromise the quality of life in some patients.

Sacral neuromodulation (SNM)

Although the exact mechanism of action of SNM is still not well understood, several mechanisms of action have been postulated, such as the correction of a disturbed reflex action, or using a ‘rebound’ phenomenon in the CNS through afferent pathway stimulation to the brain area that controls bladder and sphincter function. Therefore, to our knowledge, electrical neuromodulation should not work in patients with a complete spinal cord injury [4]. Moreover, SNM can only work if the detrusor is still able to contract, so a chronically over-distended bladder with recurrent UTI, and therefore a large fibrotic bladder, is unsuitable either for SNM or IVES.

Nevertheless, SNM is a minimally invasive treatment for chronic unobstructed urinary retention in women [48] and which offers an effective therapeutic alternative to CIC or indwelling catheterisation. After SNM, up to 72% of women could void spontaneously, with a mean PVR of 100 mL, and half no longer needed CIC [49]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis [50] the overall success rate for neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction was 68% for the test phase and 90% in those patients who received the implant. However, the methods and data reported vary widely, with no clear differentiation between the indications for DU or DO. Randomised controlled trials are needed before drawing conclusions on the value of SNM in neurogenic DU.

Surgical treatment for an acontractile detrusor (functional detrusor myoplasty)

Detrusor myoplasty was first described by Stenzl et al. [51], and Gakis et al. [52] reported the long-term results of latissimus dorsi detrusor myoplasty in neurogenic patients with detrusor acontractility, reporting that 71% gained complete spontaneous voiding, with a mean PVR of 25 mL. However, this interesting study represents the experience of only one group, not yet reproduced by others, and with few patients [24]. Hence we should not be too optimistic about their results until larger trials with more patients are available.

Future developments

DU could be a target for stem-cell therapy to restore the contractile function of the bladder, but neither experimental nor clinical data are available. Direct electrical stimulation of the acontractile detrusor was developed by Merrill in the 1970s, with remarkable results [53], but technical failures and infections were the main drawbacks. Moreover, in this period CIC became popular as an effective method to empty the acontractile bladder. It might be that with current technology and the improved knowledge of bladder pathophysiology effective direct electrostimulation of the bladder would be possible [54].

The treatment of BOO

Mechanical BOO

For iatrogenic BOO after treating stress urinary incontinence, e.g., after placing a MUS, if patients present with voiding difficulty this can be managed with a short-term (1 week) urethral catheterisation, and in most patients it resolves spontaneously [55]. Only a few women (1%) will develop chronic urinary retention. These patients should be offered CIC or a suprapubic catheter, with a close follow-up. If there is no improvement in symptoms, or in women who are unwilling to use CIC, division of the mesh should be offered. The tape should be divided within the first 3 weeks after surgery, to avoid permanent features of urethral distortion resulting from the progressive fibroblastic reaction around the polypropylene mesh [56]. Obstruction occurring after a Burch colposuspension could be treated by removing the obstructing sutures fixing the urethra to Cooper’s ligament.

BOO due to POP is successfully treated with surgery of the POP. Up to 74% of patients who had the cystocele repaired with anterior colporrhaphy or a polypropylene mesh repair had an improvement in their voiding difficulties [57].

For a urethral stricture, urethral dilatation and internal urethrotomy have a high recurrence rate. With a rigid, narrow urethra some type of urethroplasty (a vaginal inlay flap, Blandy urethroplasty, or dorsal vaginal graft urethroplasty) might be necessary.

Functional BOO

For dyscoordinated voiding or ‘Hinman syndrome’, the management of voiding includes biofeedback and bladder retraining programmes. Patients must be aware that they have a false micturition behaviour. With the help of a physiotherapist and biofeedback they must learn to relax the PFM during voiding. A suitable tool is the recording of the EMG of the PFM by self-adhesive surface electrodes which are connected to earphones. The patient is then acoustically informed whether she relaxes or contracts the PFM during micturition [58]. In severe cases (with a PVR of >50% of the functional bladder capacity), at least initially, CIC should be offered.

For primary bladder neck obstruction, the use of α-blockers might be useful. In women with functional BOO who were treated with tamsulosin, Costantini et al. [59] reported an improvement in voiding symptoms in 71.4%, a decrease of the PVR in 62.5% and a 66.7% improvement in both voiding and storage symptoms. Transurethral incision of bladder neck, although advised by several authors, risks postoperative urinary incontinence [60,61].

For DSD, CIC is still the standard treatment, thus by passing the dyssynergic sphincter. For women unable to use CIC an injection with botulinum toxin A (BTA) into their striated sphincter is an option, but must be repeated every 3 months [62]. An injection with BTA for treating neurogenic DSD was first introduced by Dykstra and Sidi [63]. Up to 67% of patients reported an improvement in voiding [64]. Other pharmacotherapy for DSD is difficult, e.g., striated muscle relaxants (e.g. Baclofen) are effective only in high doses and are associated with a variety of side-effects which minimise their overall usefulness. There is no study showing that oral α-blockers improve DSD [62].

For patients with an established diagnosis of Fowler’s syndrome, SNM has been shown to be most effective in up to 72% [65].

Conclusions

Some 6% of women have voiding difficulties, which are complex conditions and have several possible causes, the most frequent of which is DU; BOO in females is relatively uncommon but a combination of DU and BOO is possible.

As urinary symptoms have a poor correlation with the underlying pathophysiology, urodynamic and imaging studies are crucial for the appropriate diagnosis, especially to differentiate between DU and BOO, and to determine the management.

A complete cure might not be possible for every woman with VD, and therefore relieving the symptoms and minimising the long-term complications associated with it should be the goal. With DU, behavioural therapy should be offered first to improve the condition. CIC is important, especially for those with a high PVR. The use of IVES and SNM as minimally invasive treatment options should be offered to women with some preserved function of detrusor sensitivity and contractility. For mechanical BOO, abolishing the underlying cause (obstructed sling or POP) improves or can even normalise the condition. In women with functional obstruction, behavioural therapy to eliminate false micturitional behaviour is the first line of treatment. For severe cases CIC is an option, indwelling catheterisation is the last resort, and urinary diversion should be the rare exception for otherwise untreatable cases.

Conflict of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest.

Source of funding

None.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- 1.Coyne K.S., Sexton C.C., Thompson C.L., Milsom I., Irwin D., Kopp Z.S. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, UK and Sweden: results from the epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009;104:352–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson D., Staskin D., Laterza R.M., Koelbl H. Defining female voiding dysfunction: ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:313–316. doi: 10.1002/nau.22213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams P., Cardozo L., Fall M., Griffiths D., Rosier P., Ulmsten U. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the standardization sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–178. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Koeveringe G.A., Vahabi B., Andersson K.E., Kirschner-Herrmans R., Oelke M. Detrusor underactivity: a plea for new approaches to a common bladder dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:723–728. doi: 10.1002/nau.21097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Sèze M., Ruffion A., Denys P., Joseph P.A., Perrouin-Verbe B. GENULF. The neurogenic bladder in multiple sclerosis review of the literature and proposal of management guidelines. Mult Scler. 2007;13:915–928. doi: 10.1177/1352458506075651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloch F., Pichon B., Bonnet A.M., Pichon J., Vidailhet M., Roze E. Urodynamic analysis in multiple system atrophy. Characterization of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia. J Neurol. 2010;257:1986–1991. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tibaek S., Gard G., Klarskov P., Iversen H.K., Dehlendorff C., Jensen R. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in stroke patients: a cross-sectional, clinical survey. Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27:763–771. doi: 10.1002/nau.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G.D., Lin L.Y., Wang P.H., Lee H.S. Urinary tract dysfunction after radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:292–297. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lange M.M., van de Velde C.J.H. Urinary and sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment. Nature Rev Urol. 2011;5:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abarbanel J., Marcus E.L. Impaired detrusor contractility in community-dwelling elderly presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology. 2007;69:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madersbacher S., Pycha A., Schatzl G., Mian C., Klingler C.H., Marberger M. The aging lower urinary tract. A comprehensive urodynamic study of men and women. Urology. 1998;51:206–212. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnick N.M., Yalla S.V. Detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractile function. An unrecognized but common cause of incontinence in elderly patients. JAMA. 1987;12:3076–3081. doi: 10.1001/jama.257.22.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ismail S.I., Emery S.J. The prevalence of silent postpartum retention of urine in a heterogeneous cohort. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:504–507. doi: 10.1080/01443610802217884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madersbacher H., Cardozo L., Chapple C., Abrams P., Toozs-Hobson P., Young J.S. What are the causes and consequences of bladder overdistension? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:317–321. doi: 10.1002/nau.22224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moller C.F. Diabetic cystopathy. I. A clinical study of the frequency of bladder dysfunction in diabetics. Dan Med Bull. 1976;23:267–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirschner-Hermanns R., Daneshgari F., Vahabi B., Birder L., Oelke M., Chacko S. Does diabetes mellitus-induced bladder remodeling affect lower urinary tract function? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:359–364. doi: 10.1002/nau.22228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee W.C., Wu H.P., Tai T.Y., Yu H.J., Chiang P.H. Investigation of urodynamic characteristics and bladder sensory function in the early stages of diabetic bladder dysfunction in women with type 2 diabetes. J Urol. 2009;181:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Q., Ritchie J., Marouf N., Dion S.B., Resnick N.M., Elbadawi A. Role of ovarian hormones in the pathogenesis of impaired detrusor contractility: evidence in ovariectomized rodents. J Urol. 2001;166:1136–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buntzen S., Nordgren S., Delbro D., Hultén L. Anal and rectal motility responses to distension of the urinary bladder inman. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10:148–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00298537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romanzi L.J., Chaikin D.C., Blaivas J.G. The effect of genital prolapse on voiding. J Urol. 1999;161:581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karantanis E., Fynes M.M., Stanton S.L. The tension-free vaginal tape in older women. BJOG. 2004;111:837–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daraï E., Frobert J.L., Grisard-Anaf M., Lienhart J., Fernandez H., Dubernard G. Functional results after the suburethral sling procedure for urinary stress incontinence. A prospective randomized multicentre study comparing the retropubic and transobturator routes. Eur Urol. 2007;51:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinman F., Jr Non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder (the Hinman syndrome): 15 years later. J Urol. 1986;136:769–777. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fowler C.J., Kirby R.S. Abnormal electromyographic activity (decelerating burst and complex repetitive discharges) in the striated muscle of the urethral sphincter in 5 women with persisting urinary retention. Br J Urol. 1985;57:67–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1985.tb08988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowenstein L., Anderson C., Kenton, Dooley Y., Brubaker L. Obstructive voiding symptoms are not predictive of elevated post void residual urine volumes. Int Urogynaecol J. 2008;19:801–804. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0530-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Sharani M., Lovatis D. Do subjective symptoms of obstructive voiding correlate with the post void residual urine in women? Int Urogynaecol J. 2008;16:12–14. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo H.C. Clinical symptoms are not reliable in the diagnosis of lower urinary tract dysfunction in women. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson K.V., Rome S., Nitti V.W. Dysfunctional voiding in women. J Urol. 2001;165:143–147. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang W.C., Yang S.H., Yang J.M. Application of ultrasonography in female voiding dysfunction. Incont Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;2:41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ku J.H., Jeong I.G., Lim D.J., Byun S.S., Paick J.S., Oh S.J. Voiding diary for the evaluation of urinary incontinence and lower urinary tract symptoms: prospective assessment of patient compliance and burden. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:331–335. doi: 10.1002/nau.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thuroff J.W., Abrams P., Andersson K.E., Artibani W., Chapple C.R., Drake M.J. EAU guidelines on urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2011;59:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrams P., Andersson K.E., Birder L., Brubaker L., Cardozo L., Chapple C. Fourth international consultation on incontinence recommendations of the international scientific committee: evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:213–240. doi: 10.1002/nau.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffiths D.J., van Mastrigt R., Bosch R. Quantification of urethral resistance and bladder function during voiding, with special reference to the effects of prostate size reduction on urethral obstruction due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Neurourol Urodyn. 1989;8:29–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schafer W. Analysis of bladder-outlet function with the linearized passive urethral resistance relation, linPURR, and a disease-specific approach for grading obstruction: from complex to simple. World J Urol. 1995;13:47–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00182666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abrams P. Bladder outlet obstruction index, bladder contractility index and bladder voiding efficiency: three simple indices to define bladder voiding function. BJU Int. 1999;84:14–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groutz A., Blaivis J.G., Chaikin D.C. Bladder outlet obstruction in women. Definition and characteristics. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:213–220. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(2000)19:3<213::aid-nau2>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuo H.C. Videourodynamic characteristics and lower urinary tract symptoms of female bladder outlet obstruction. Urology. 2005;66:1005–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nitti V.W., Tu L.M., Gitlin J. Diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction in women. J Urol. 1999;161:1535–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diokno A.C., Hollander J.B., Bennet C.J. Bladder neck obstruction in women: a real entity. J Urol. 1984;132:294–298. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Espino-Strebel E.E., Luna J.T., Domingo E.J. A comparison of the feasibility and safety of nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy with the conventional radical hysterectomy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:1274–1283. doi: 10.1111/igc.0b013e3181f165f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ameda K., Kakizaki H., Koyanagi T., Hirakawa K., Kusumi T., Hosokawa M. The long-term voiding function and sexual function after pelvic nerve-sparing radical surgery for rectal cancer. Int J Urol. 2005;12:256–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Constantinou C., Schmidt F., Djurhuus J. Optimum bladder capacity for minimum bladder work in normal male micturition. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:349–350. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barendrecht M.M., Oelke M., Laguna M.P., Michel M.C. Is the use of parasympathomimetics for treating an underactive urinary bladder evidence-based? BJU Int. 2007;99:749–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madersbacher H, Katona F, Berenyi M. Intravesical electrical stimulation of the bladder. In: Corcos J, Scick E, editor. Neurogenic Bladder, 2nd ed. 2008. pp. 624–9 [55].

- 45.Huber E.R., Kiss G., Berger T., Rehder P., Madersbacher H. The value of intravesical electrostimulation in the treatment of acute prolonged bladder overdistension. Urologe A. 2007;46:662–666. doi: 10.1007/s00120-007-1312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lombardi G., Celso M., Mencarini M., Nelli F., Del Popolo G. Clinical efficacy of intravesical electrostimulation on incomplete spinal cord patients suffering from chronic neurogenic non-obstructive retention: a 15-year single centre retrospective study. Spinal cord. 2013;51:232–237. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grigoleit U., Pannek J., Stohrer M. Single-use intermittent catheterization. Urologe A. 2006;45:175–182. doi: 10.1007/s00120-006-1007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elneil S. Urinary retention in women and sacral neuromodulation. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(Suppl. 2):S475–S483. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1277-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Datta S.N., Chaliha C., Singh A., Gonzales G., Mishra V.C., Kavia R.B. Sacral neurostimulation for urinary retention: 10-year experience from one UK centre. BJU Int. 2008;101:192–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kessler T.M., La Framboise D., Trelle S., Fowler C.J., Kiss G., Pannek J. Sacral neuromodulation for neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2010;58:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stenzl A., Ninkovic M., Kolle D. Restoration of voluntary emptying of the bladder by transplantation of innervated free skeletal muscle. Lancet. 1998;351:1483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stenzl A., Ninkovic M., Kölle D., Knapp R., Anderl H., Bartsch G. Functional detrusor myoplasty for bladder acontractility: long-term results. J Urol. 2011;185:5939. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merrill DC. Electrical stimulation of the neurogenic bladder. Elektrostimulation der gelähmten Blase Hauptverband der Gewerblichen Berufsgenossenschaften. V. Bonn 1977 Heft. 2.

- 54.Walter J.S., Allen J.C., Sayers S., Singh S., Cera L., Wheeler J.S. Evaluation of bipolar Permaloc™ electrodes for direct bladder stimulation. Open Rehabil J. 2012:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daneshgari F., Kong W., Swartz M. Complications of mid urethral slings: important outcomes for future clinical trials. J Urol. 2008;180:1890–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leng W.W., Davies B.J., Tarin T., Sweeney D.D., Chancellor M.B. Delayed treatment of bladder outlet obstruction after sling surgery: association with irreversible bladder dysfunction. J Urol. 2004;172:1379–1381. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000138555.70421.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fletcher S.G., Haverkorn R.M., Yan J., Lee J.J., Zimmern P.E., Lemack G.E. Demographic and urodynamic factors associated with persistent OAB after anterior compartment prolapsed repair. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:1414–1418. doi: 10.1002/nau.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chase J., Austin P., Hoebeke P., McKenna P. International children’s continence society. The management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a report from the standardization committee of the international children’s continence society. J Urol. 2010;183:1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costantini E., Lazzeri M., Bini V., Zucchi A., Fioretti F., Frumenzio E. Open-label, longitudinal study of tamsulosin for functional bladder outlet obstruction in women. Uro Int. 2009;83:311–315. doi: 10.1159/000241674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blaivas J.G., Flisser A.J., Tash J.A. Treatment of primary bladder neck obstruction in women with transurethral resection of the bladder neck. J Urol. 2004;171:1172–1175. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000112929.34864.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng C.H., Kuo H.C. Transurethral incision of bladder neck in treatment of bladder neck obstruction in women. Urology. 2005;65:275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahfouz W., Corcos J. Management of detrusor external sphincter dyssynergia in neurogenic bladder. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;47:639–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dykstra D.D., Sidi A.A. Treatment of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia with botulinum A toxin: a double-blind study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:24–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phelan M.W., Franks M., Somogyi G.T., Yokoyama T., Fraser M.O., Lavelle J.P. Botulinum toxin urethral sphincter injection to restore bladder emptying in men and women with voiding dysfunction. J Urol. 2005;165:1107–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Ridder D., Ost D., Bruyninckx F. The presence of Fowler’s syndrome predicts successful long-term outcome of sacral nerve stimulation in women with urinary retention. Eur Urol. 2007;51:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]