Abstract

Education scholars document notable racial differences in teachers’ perceptions of students’ academic skills. Using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort, this study advances research on teacher perceptions by investigating whether racial differences in teachers’ evaluations of first grade students’ overall literacy skills vary for high, average, and low performing students. Results highlight both the overall accuracy of teachers’ perceptions, and the extent and nature of possible inaccuracies, as demonstrated by remaining racial gaps net literacy test performance. Racial differences in teachers’ perceptions of Black, non-White Latino, and Asian students (compared to White students) exist net teacher and school characteristics and vary considerably across literacy skill levels. Skill specific literacy assessments appear to explain the remaining racial gap for Asian students, but not for Black and non-White Latino students. Implications of these findings for education scholarship, gifted education, and the achievement gap are discussed.

Keywords: Teacher perceptions, Academic performance, Race/ethnicity, ECLS-K, Literacy skills

1. Introduction

In recent years, scholars have directed considerable attention to racial achievement gaps, documenting huge differences in school readiness and academic growth during students’ formative years of schooling (Alexander, Entwisle, and Horsey, 1997; Harris, 2011; Harris and Robinson, 2007). While some have focused on factors associated with lack of preparation and poor performance among minority youth (Lee and Burkam, 2002; Washington, 2001), others have documented a myriad of challenges among high achieving and gifted minority students (Ford, 1998; Ford, Grantham, and Whiting, 2008). In both cases, scholars point to the teacher-student relationship as central to understanding young students’ schooling experiences (Alexander, Entwisle and Thompson, 1987; Crosnoe et al., 2010; Easton-Brooks and Davis, 2009; Ford et al., 2001).

The influence that teachers’ perceptions and expectations have on quality teacher-student interaction (Davis, 2003), academic placement decisions (Baudson and Preckel, 2013), and students’ academic performance (Mckown and Weinstein, 2008) motivate the present study, which considers the relationship between race and teachers’ overall assessment of first grade students’ literacy skills.1 As recommended by Hoge and Coladarci (1989), this study focuses on the extent to which students’ cognitive ability not only mediates but also moderates the relationship between students’ race and teacher assessments. The major contribution of this work is in identifying the presence and nature of unexplained racial/ethnic variance (i.e. racial/ethnic gaps) in teacher perceptions for students who demonstrate low, average, and high levels of cognitive literacy skills.

A number of studies across elementary, middle, and high school contexts have documented noticeable racial/ethnic differences in teacher assessments of academic ability and social behavior (Downey and Pribesh, 2004; Ferguson, 2003; Harris, 2011; McGrady and Reynolds, 2013; McKown and Weinstein, 2008; Morris, 2005b; Ready and Wright, 2011; Rist, 1970; Tenenbaum and Ruck, 2007). Recognizing the cultural disconnect between America’s teaching workforce and the diverse student populations they serve, some minority parents and teachers have challenged this narrative by encouraging academic excellence among minority youth, both as a means of social uplift and way of escaping negative stereotypes (Foster, 1990; Morris, 2005a; Tyson, 2003). Although the general consensus is that teachers’ assessments are fairly accurate (Hoge and Coladarci, 1989; Jussim and Harber, 2005), this cultural disconnect also serves as a primary impetus for much of the emergent scholarship focused on fleshing out the effects of students’ cognitive abilities and actions, as opposed to other demographic or contextual factors, on teacher perceptions (Bates and Glick, 2013; Downey and Pribesh, 2004; McKown and Weinstein, 2008; Ready and Wright, 2011).

To address the issue of accuracy in teacher perceptions, Ready and Wright (2011) focused on within-classroom effects on Academic Rating Scale (ARS) assessment scores, which were derived from teachers’ ratings of a number of different literacy skills. Although they found evidence of unexplained racial gaps early in the school year, by spring, racial gaps were largely, if not entirely, explained by student performance. What Ready and Wright did not examine, however, was teachers’ general or overall perceptions of student literacy. While skill specific assessments may inform some placement decisions, teachers’ decisions to refer or nominate students are also likely influenced by their general sense of student ability and/or risk, especially in cases where specific assessments and general perceptions do not align.

The ongoing debate regarding the challenges of high and low achieving minority students highlights the importance of not only assessing whether perceptions reflect actual abilities, but also examining whether possible racial gaps in perceptions vary across levels of achievement. Because many racial stereotypes in education are tied to deficit thinking related to student intelligence (Ford et al., 2002), teachers’ evaluations of students may simultaneously be informed by students’ race/ethnicity and cognitive ability.2 This study, which examines the extent to which students’ cognitive skills both mediate and moderate the relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teacher perceptions, is guided by three research questions:

Are there racial gaps in teachers’ perceptions of students’ overall literacy skills? If so, to what extent are these differences a reflection of difference in actual abilities?

Is academic ability (as measured by test scores) merely a mediator of the relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions or does ability also serve as a moderator of this relationship?

What does the relationship between students’ and teachers’ perceptions look like at different points on the distribution of ability, net student, teacher, and school-level characteristics?

2. Background and literature review

2.1. Teachers’ perceptions and student outcomes

Scholars find that teachers’ perceptions can shape student learning and social development, largely through their influence on teacher-student interaction (Chaiken, Sigler, and Derlega, 1974; Hallinan, 2008; Irvine, 1988; Leacock, 1982; Montalvo, Mansfield, and Miller, 2007; Rosenthal and Jacobson, 1968). This relationship is most palpable during elementary school, because students spend most of the day interacting with a single teacher (Hamre and Pianta, 2001; Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, and Essex, 2005). In the early grades, individual teachers are almost solely responsible for relaying academic content, organizing physical activities, supervising social communication, providing emotional support, and teaching important social skills (Doll, 1996; Pianta, 1997), positioning them as strong socializing forces and central academic gatekeepers.

Within the elementary school context, positive perceptions can increase the likelihood of positive interpersonal interactions between teachers and their students (Davis, 2003), whereas negative perceptions may increase a student’s likelihood of being criticized and decrease their likelihood of being called on or offered effective feedback (Brophy and Good, 1970; Good, 1981; Good and Brophy 1972; Rist, 1970). Negative perceptions may also bring about or magnify teacher-student conflict, which can result in poor cooperation in the classroom (Birch and Ladd 1997), chronic underachievement (Mandel and Marcus, 1988; McCall, Evahn, and Kratzer, 1992), and grade retention or dropping out (Hughes, Cavell, and Wilson, 2001; Ladd, Birch, and Buhs, 1999; Pianta, Steinberg, and Rollins, 1995). Furthermore, through their relationship with teacher expectations, teachers’ perceptions can also influence the quality of teacher instruction, as well as students’ academic potential, emotional stability, sociability, interests, and motivation (Farkas et al., 1990; Jussim and Harber, 2005; McKown and Weinstein, 2008; Midgley, Feldlauffer, and Eccles, 1989; Rosenthal and Jacobson, 1968; Wong, 1980). Although studies have evaluated the influence of teachers’ perceptions across many age groups, scholars often point to the early years of schooling as one of the most critical periods (Entwisle and Hayduk, 1988; Farkas, 2003; Hamre and Pianta, 2001; Rowan, Correnti, and Miller, 2002).3

Evidence suggests that teachers’ perceptions may also play an important role in decisions related to grade retention, ability grouping, and academic placements (Alexander et al., 1997; Burkam, LoGerfo, Ready, and Lee, 2007; Condron, 2007; Entwisle and Alexander, 1992; Entwisle, Alexander, and Olson, 1998; Farkas, 2003; Page, 1987; Pianta et al., 1995; Smith and Shepard, 1988). Some gaps in student placements and grade retention do reflect actual differences in students’ needs, skills, and level of risk; however, evidence suggests that teachers’ perceptions may also influence decisions net these characteristics. For example, Pianta and colleagues (1995) find that for students with similar levels of risk, having a positive teacher-student relationship decreases the likelihood of being retained in kindergarten or referred to special education.

Teachers’ perceptions may also influence more desirable placements, such as upper ability groups and gifted education programs (Ford et al., 2002). Although most teachers have little training in gifted education (Archambault et al., 1993; Karnes and Whorton, 1991), the majority of states use teacher nominations, referrals, and input to identify and decide which students will receive gifted education services (Coleman, Gallagher, and Foster, 1994). These decisions are informed by how well a student performs academically but also by perceptions of seemingly irrelevant or subjective behaviors such as cooperation, promptness, and tidiness (Copenhaver and McIntyre, 1992; Cox, Daniels, and Boston, 1985).4

2.2. Students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions

Scholars find that Black and/or Latino students tend to receive lower ratings from teachers than White and Asian students across a number of dimensions, including academic ability and achievement (Ferguson, 2003; McKown and Weinstein, 2008; Murray, 1996; Oates, 2003; Ready and Wright, 2011), academic engagement and approaches to learning behaviors (Downey and Pribesh, 2004; Masten et al., 1999; McGrady and Reynolds, 2013; Pigott and Cowen, 2000), problem behaviors (Downey and Pribesh, 2004; McGrady and Reynolds, 2013; Pigott and Cowen, 2000), and physical appearance and presentation of self (Ferguson, 2000; Morris, 2005b). Scholars have also noted racial variation in teachers’ reactions to students who exhibit similar behaviors (Entwisle and Alexander, 1988; Murray, 1996; Partenio and Taylor, 1985).

Empirical evidence suggests that teachers’ assessments, particularly academic assessments, are fairly accurate (Jussim and Eccles, 1992, Jussim and Harber, 2005; Jussim, Eccles and Madon, 1996; Ready and Wright, 2011; Meisels et al., 2001); however, Jussim and Harbor (2005) highlight that nearly a quarter of the predictive validity of teachers’ assessments may be driven by the effects of self-fulfilling prophesy. These expectancy effects are even stronger for students whose teachers engage in differential treatment (Brattesani et al., 1984), for students placed in lower ability groups (Smith et al., 1998), and for students from stigmatized groups (Jussim et al., 1996; Madon, Jussim, and Eccles, 1997). Scholars also find evidence of lower teacher expectations among high achieving and gifted minority students (Ford, 1996; McKown and Weinstein, 2008). In general, perceived differences across racial/ethnic groups tend to align with actual differences in achievement (Jussim et al., 1996); however, researchers have documented instances where teachers’ perceptions did not reflect empirical reality (Downey and Pribesh, 2004; McGrady and Reynolds, 2013; McKown and Weistein, 2008; Ready and Wright, 2011; Murray, 1996). Even Jussim and Harber (2005) acknowledge that although the average effect size of this bias tends to be fairly small, these small effects can have a huge impact on inequality.

Scholars also find racial differences in the effects of teachers’ perceptions and in the outcomes they predict. For example, teachers’ perceptions are much stronger predictors of Black students’ perceptions of their own academic ability—an important predictor of academic success—than they are of White students’ self-perceptions (Kleinfeld, 1972; Irvine, 1990). Notably, scholars focusing on academic performance and social development have come to similar conclusions (Burchinal et al., 2002; Entwisle and Alexander, 1988; Jussim et al., 1996; Mckown and Weinstein, 2002; Meehan, Hughes, and Cavell, 2003). Additionally, Black and Latino students not only receive fewer positive referrals (such as honors or gifted placement) and more negative referrals (such as special education or discipline-related sanctioning compared to White and Asian students, but also hear more negative language in teacher-student interactions (Tenenbaum and Ruck, 2007).

Researchers have identified two additional issues specific to high-achieving and gifted minority students: access to academically advanced and gifted educational opportunities (Ford et al., 2001; Serwatka, Deering, and Stoddard, 1989) and underachievement (Ford, 1995; Kolb and Jussim, 1993). Regarding access, scholars find that minority students are not only underrepresented in gifted programs (Farkas, 2003; Ross et al., 1993), but are also systematically under-referred for these programs (Ford, 1995, 1998; Elhoweris et al., 2005; Saccuzzo, Johnson, and Guertin, 1994). Furthermore, Ford (1995) estimates that nearly half of gifted Black students experience some level of underachievement—a finding echoed in previous studies (Mandel and Marcus, 1988; McCall et al., 1992)—which influence student interest in school and motivation, and increases the likelihood of problematic teacher-student relationships.

Although research aimed at understanding racial differences in teacher perceptions is ongoing, many education scholars agree that these differences are in some way related to deficit thinking—the assumption or stereotype that Black and Latino students are academically and socially deprived or deficient relative to their White and Asian counterparts (Burnstein and Cabello, 1989; Chang and Demyan, 2007; Ford et al., 2002; McGrady and Reynolds, 2013; Menchaca, 1997; Solorzano, 1997; Solorzano and Solorzano, 1995; Valencia, 2002). Despite evidence to the contrary (Downey, 2008; Downey, Ainsworth, and Qian, 2009; Harris, 2006, 2011; Tyson, 2011), deficit thinking is reinforced by the widely held belief that Black and Latino students hold oppositional attitudes towards education (Harris, 2011; Fordham and Ogbu, 1986). For example, Jackson (2002) finds that White teachers tend to attribute Black and Latino students’ problem behaviors to personal and dispositional factors, while blaming White students’ problem behaviors on external and situational factors.

2.3. Linking race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions

Below, I present three hypotheses regarding the relationship between race, cognitive ability, and teacher perceptions of overall literacy skills.

Hypothesis 1: The relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions is fully mediated by students’ cognitive literacy skills.

If hypothesis 1 is true, any racial/ethnic variation in teachers’ perceptions of overall literacy skills evident in the based model is fully explained by students’ demonstrated cognitive ability (based on literacy assessment scores). This suggests that any racial differences in teachers’ perceptions are likely a reflection of true differences in the population.

Hypothesis 2: Students’ cognitive literacy skills partially mediate, but do not moderate, the relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions.

If hypothesis 2 is true, this means that cognitive ability explains some (but not all) of the racial/ethnic variation in teachers’ perceptions, and that the remaining racial variation in teachers’ perceptions of overall literacy skills is consistent across low, average, and high achieving students. This suggests that possible inaccuracies in teachers’ perceptions (as determined by remaining racial gaps) are the same for students across the spectrum of cognitive ability.

Hypothesis 3: Students’ cognitive literacy skills both mediate and moderate the relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions.

If hypothesis 3 is true, this means that cognitive ability explains some of the racial/ethnic variation in teachers’ perceptions, but in this case, the remaining racial variation in teachers’ perceptions is not the same for low, average, and high achieving students. This suggests that possible inaccuracies in teachers’ perceptions (as determined by remaining racial gaps) are different for students at different points on the spectrum of cognitive ability.

Hypothesis 3 points to a possible interaction effect between students’ race and cognitive ability. If I were to find that negative perceptions of minority students (relative to white students) are more prevalent among students with below average performance, minority students with lower levels of cognitive literacy skills may face a double penalty or cumulative effect across stigmas, similar to what Jussim and colleagues (1996) find for race and income. This finding would then lend support for the belief that students of color can escape negative stereotyping through academic excellence. Conversely, if negative perceptions of minority students (relative to white students) are more likely to occur among high achievers, this would suggest a paradox whereby teachers may be systematically underestimating the potential of higher achieving students of color relative to their White and Asian peers, a phenomenon highlighted by Ford and colleagues (2002).

3. Data

Data for this study are drawn from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99 (ECLS-K), which is supplemented with school-level information from the Common Core of Data; both are sponsored by the National Center for Education Statistics. The ECLS-K is a nationally representative sample of students who were enrolled in kindergarten during the fall of 1998. Sampling for the ECLS-K followed a two-stage stratified probability design, with approximately 1,280 schools sampled at stage one and 22,780 students sampled at stage two. This study focuses on spring of students’ first grade year (wave 4) but also utilize test score data from spring of their kindergarten year (wave 2).

My analytical sample is restricted to students who were enrolled in first grade during the spring of 2000, participated in the first wave of data collection, and had valid literacy test scores for spring of kindergarten and spring of first grade. Students with missing data for the variables use in the analysis or who did not fall into one of the racial/ethnic categories described below were also excluded, resulting in a final analytic sample of 10,740 students.5

3.1. Dependent Variable

My dependent variable is teachers’ rating of student’s overall language and literacy skills. Teachers were asked to provide an overall rating of their student’s language and literacy skills compared to other students of the same grade by selecting one of five answer options ranging from far below average to far above average. Unlike the literacy ARS scores, which focus on students’ level of proficiency across nine specific literacy skills, my dependent variable captures teachers’ general sense students’ overall ability relative to other first grade students.

3.2. Student’s race/ethnicity

I include five racial/ethnic groups in my analyses: White, Asian, White Latino, non-White Latino, and Black. The White and Black racial groups are both non-Hispanic; however, Asians who also identified as Latino (mostly Filipino) were placed in the Asian category, as were Pacific Islanders. Latinos were divided into two groups, White Latinos, which only includes Latinos who do not identify a non-White racial identity, and non-White Latinos, which includes all other non-Asian Latinos. Non-Hispanic students who identified as Black or had at least one biological parent who identified as Black were placed in the Black racial group. As noted in Table 1, the sample for this study is about 65 percent White, 7 percent Asian, 7 percent White Latino, 7 percent non-White Latino, and 15 percent Black.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (ECLS-K 1998–99: First Grade, N = 10,740)

| %/ Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student-Level | ||||

| White | 64.7 | |||

| Asian | 6.7 | |||

| White Latino | 6.5 | |||

| Non-White Latino | 7.3 | |||

| Black | 14.6 | |||

| Kindergarten Literacy Score | 34.0 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 85.0 |

| Standardized | 0.0 | 1.0 | −2.1 | 4.8 |

| First Grade Literacy Score | 57.5 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 89.0 |

| Standardized | 0.0 | 1.0 | −3.5 | 2.5 |

| Male | 50.5 | |||

| Socioeconomic Status | 0.1 | 0.8 | −3.0 | 2.9 |

| Age (in months) | 87.1 | 4.4 | 70.5 | 110.1 |

| ARS Literacy Assessment Score | 3.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Approaches to Learning (Teacher) | 3.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Approaches to Learning (Parent) | 3.1 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 4.0 |

| Teacher-Level | ||||

| White (reference) | 86.9 | |||

| Black | 6.6 | |||

| Hispanic | 3.6 | |||

| Other | 3.0 | |||

| Up to Bachelor’s Degree | 30.7 | |||

| Graduate Coursework (reference) | 32.1 | |||

| Master’s Degree | 30.8 | |||

| Doctorate/ Education Specialist | 6.4 | |||

| Age | 42.5 | 11.0 | 22.0 | 73.0 |

| Class Reading Level | ||||

| % Reading Below Grade Level | 27.9 | 26.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| % Reading Above Grade Level | 32.6 | 27.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| School-Level | ||||

| Percent Poverty | 55.3 | 40.1 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Percent Asian | 5.0 | 13.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Percent Hispanic | 11.8 | 21.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Percent Black | 15.1 | 25.1 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Public School | 80.5 | |||

| City (reference) | 32.0 | |||

| Suburb | 37.9 | |||

| Town/Rural | 30.1 | |||

| Northeast | 18.7 | |||

| Midwest | 26.1 | |||

| South (reference) | 35.6 | |||

| West | 19.7 | |||

3.3. Cognitive Literacy Skills

I use two ECLS-K cognitive assessments as indicators of cognitive ability. These assessments, which were administered to students in person using computer assisted technology, included questions on letter recognition, beginning and ending sounds, sight words, and word comprehension. Literacy test scores for spring of kindergarten and spring of first grade were subsequently developed using item response theory. Reading test scores for the sample ranged from just over 10 point to almost 90 points, with a mean score of about 34 in kindergarten and 58 in first grade.

3.3. Model Controls

Additional student-level covariates include gender (male = 1), socioeconomic status (SES), and age (in months). Students’ SES is a standardized composite measure developed by ECLS-K that included information from parents’ income, education, and occupational prestige. Teacher-level covariates include race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, and other), educational attainment (up to a bachelor’s degree, graduate coursework, master’s degree, and doctorate/ education specialist), and age. I also include two variables for teachers’ perceptions of their classroom’s ability level: percent of students reading above grade level and percent reading below grade level. School-level covariates include the percent of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, percent Asian, Hispanic, and Black students, whether the school is a public school or not, locality (city, suburb, town/rural) and region.

I also include students’ ARS literacy assessment scores as well as both teachers’ and parents’ ratings of students’ learning behaviors. For teachers, the Approaches to Learning scale was composed of six questions that asked teachers to rate on a four-point scale the frequency with which the student exhibited the following behaviors: organization, eagerness to learn, independence, adaptation, task persistence, and paying attention. For parents, the Approaches to Learning scale is also composed of six questions that focus on similar behaviors, including task persistence, interest, concentration, eagerness to learn, creativity, and helpfulness.

4. Analytical Technique

I begin by evaluating the bivariate relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ overall rating of literacy skills. Next, I present multivariate models that examine the extent to which teachers’ perceptions vary by race/ethnicity. One important issue is how to best account for cognitive ability. Although the skills assessed on the ECLS-K cognitive literacy tests parallel those rated by teacher in the ARS literacy rating, it is unlikely that a single test score will accurately reflect a students’ overall cognitive ability. To address possible measurement error in the use of one year’s tests scores as a proxy for cognitive ability, I instrument students’ first grade literacy test scores with their literacy test scores from spring of the previous year, treating both tests scores as indicators of unobserved cognitive ability (Woodridge, 2002).6 Three-level fixed and random effects ordered probit models with a continuous endogenous regressor were estimated using the Stata user-written cmp program.7 All models were estimated using factor variable notation to ensure that both the main and interaction terms for first grade test scores were properly instrumented. With the exception of students’ race and IRT test scores, all covariates in these models are grand-mean centered.

Before finalizing the structure of my multivariate models, I examined the possibility of a nonlinear relationship between test scores and teachers’ perceptions using residual plots and Stata’s linktest command. The results of these tests indicated a possible curvilinear relationship between test scores and teachers’ perceptions in the pooled fixed effect model. Although a second-order polynomial for literacy test scores was significant in the pooled fixed effect model, my overall findings remained. Furthermore, including teacher and school-level random intercepts into the model rendered the non-linear relationship between test scores and teachers’ perceptions insignificant, suggesting that the curvilinear relationship was primarily an artifact of nesting.

Estimates from my multivariate analyses are presented in three tables. The first table introduces three models, the base model, which includes fixed effects for students’ race/ethnicity and level 2 and 3 random intercepts, a second model that adds instrumented literacy assessment scores, and a third model that adds interaction terms for race/ethnicity and test scores. The second table examines changes to the best fitting model from the previous table after accounting for the effects of student, teacher, and school characteristics. The third table further examines changes to the best fitting model after controlling for ARS literacy assessment scores and for perceptions of Approaches to Learning. I also present predicted probabilities of teachers’ overall literacy skills and differences in these probabilities; the first figure focuses on the accuracy of these perceptions, while subsequent figures focus on possible inaccuracies.

5. Results

5.1. Bivariate results

Table 2 presents weighted percentage distributions of teachers’ overall literacy ratings by students’ race/ethnicity. Across all five racial/ethnic groups, the distribution of teachers’ perceptions resembles the overall distribution, with a plurality of students receiving average ratings, and only small percentages receiving extremely high or low ratings. I find little variation in the percentage of students who receive average ratings; however, there are some notable differences in the distribution of above and below average ratings across racial/ethnic groups. Focusing on the extremes, non-White Latino and Black students are about twice as likely as White, Asian, and White Latino students to be rated far below average, while both White and non-White Latino students and Black students are less likely to receive far above average ratings. The overall distributions of teachers’ perceptions demonstrate that the bulk of White, Asian and White Latino students receive either average or above average literacy ratings, while for non-White Latino and Black students, ratings are weighted more heavily toward the lower end of the distribution.

Table 2.

Percentage Distribution of Teachers’ Perceptions of Language and Literacy Skills by Students’ Race/ Ethnicity (ECLS-K 1998–99: First Grade, N = 10,740)

| White | Asian | White Latino | Non-White Latino | Black | Full Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Far Below Average | 4.6% | 3.3% | 5.6% | 7.8% | 10.6% | 6.1% |

| Below Average | 16.6% | 13.9% | 21.2% | 24.0% | 22.1% | 18.5% |

| Average | 35.3% | 36.5% | 35.5% | 36.0% | 37.9% | 35.9% |

| Above Average | 32.3% | 34.5% | 31.1% | 24.5% | 23.5% | 29.9% |

| Far Above Average | 11.1% | 11.8% | 6.6% | 7.7% | 5.9% | 9.6% |

Note: χ2 = 241.5 (16, p < .001)

5.2. Multivariate results

5.2.1. Modeling racial gaps

Because of the nested nature of the ECLS-K data, Table 3 presents estimates from three ordered probit models that include random intercepts at the classroom-level and school-level. Results from the base model (Model 1) show that teachers’ perceptions of students’ overall literacy skills are more positive for Asians than for Whites, but more negative for White Latino, non-White Latino, and Black students. Thus the racial differences in teachers’ perceptions noted in the bivariate analysis are not simply due to clustering. The question, however, is whether these differences are essentially a reflection of racial differences in students’ literacy skills, or whether they are due to something else, such as the race/ethnicity of the student.

Table 3.

Three-Level Ordered Probit Coefficients and Standard Errors for Teachers’ Perceptions of Language and Literacy Skills Regressed on Students’ Race/Ethnicity and Academic Performance (ECLS-K 1998–99: 1st Grade, N = 10,740)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Student-Level | ||||||

| Asiana | 0.121* | (0.050) | −0.020 | (0.082) | 0.014 | (0.083) |

| White Latino | −0.185*** | (0.051) | 0.083 | (0.082) | 0.083 | (0.083) |

| Non-White Latino | −0.309*** | (0.047) | 0.184 * | (0.076) | 0.152 | (0.081) |

| Black | −0.382*** | (0.036) | 0.112 | (0.059) | 0.088 | (0.062) |

| Literacy Score (standardized)b | 1.779 *** | (0.024) | 1.837 *** | (0.031) | ||

| Asian x Literacy Score | −0.164* | (0.083) | ||||

| White Latino x Literacy Score | −0.111 | (0.083) | ||||

| Non-White Latino x Literacy Score | −0.165 * | (0.076) | ||||

| Black x Literacy Score | −0.146 * | (0.058) | ||||

| Threshold 1 | −1.731*** | (0.025) | −2.688 *** | (0.031) | −2.676 *** | (0.042) |

| Threshold 2 | −0.823*** | (0.019) | −1.243 *** | (0.029) | −1.237 *** | (0.031) |

| Threshold 3 | 0.176*** | (0.017) | 0.412 *** | (0.036) | 0.418 *** | (0.029) |

| Threshold 4 | 1.270*** | (0.022) | 2.266 *** | (0.052) | 2.281 *** | (0.036) |

| Variance Component | ||||||

| Classroom Level (τ00) | 0.203 | (0.029) | 0.478 | (0.021) | 0.477 | (0.021) |

| School Level (τ00) | 0.169 | (0.022) | 0.443 | (0.023) | 0.441 | (0.023) |

| Model Statistics c | ||||||

| Deviance | 30,441 | 42,783 | 42,746 | |||

| AIC | 30,461 | 42,821 | 42,793 | |||

Includes Pacific Islanders.

Instrumented using previous year’s reading score.

Due to use of instrumental variables in Models 2 and 3, model statistics cannot be compared to Model 1.

Note: Reference category for students’ race/ethnicity is White.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

The most common method to address this question is to simply include an indicator of student ability to the model and note any changes to the aggregate differences across racial/ethnic groups, which is exactly what I do in Model 2. Accounting for student ability closes the gap between Asian and White students and reverses the gaps between non-White Latinos and Whites and between Blacks and Whites. These results suggest that teachers’ assessments of Asian students’ overall literacy skills compared to Whites’ are fairly accurate and that despite their lower than average ratings, non-White Latino students and Black students may actually be perceived more favorably than White students with similar literacy skills.

Although Model 2 estimates suggest that teachers’ overall perceptions of student literacy are more accurate than Model 1 estimates suggest, the underlying assumption of this approach is that the aggregate “effect” of race/ethnicity holds across all levels of ability. Yet, the idea that students can escape negative perceptions through improved academic performance intimates that racial gaps in teachers’ perceptions may not be constant across levels of ability. I test this possibility by including interaction terms in Model 3. Statistical significance in three of the four interaction terms confirms the presence of an interaction effect between race/ethnicity and ability. In addition, both the deviance and AIC statistics point to Model 3 as the better fitting model.

What does Model 3 tell us about the relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teacher perceptions that is different from Model 2? In Model 3, there are few changes in the coefficients for the main “effect” of race. Specifically, among average performing students—students whose scores place them around the 50th percentile—I find no significant racial/ ethnic differences in teacher ratings. However, although notably smaller than the coefficients for race/ethnicity in Model 1 and the main effect of ability in Model 3, the significant interaction terms for Asian, non-White Latino, and Black students are evidence that some of the variation in test scores may be a result of inaccurate assessments of students’ overall literacy skills. Furthermore, the direction of this relationship runs counter to the belief that minority students with higher academic performance are exempt from more negative perceptions than their white peers. Instead, it appears that among lower than average performers, teachers tend to rate Asian, non-White Latino, and Black students more positively than their White counterparts, whereas among higher than average performers, the reverse is true.

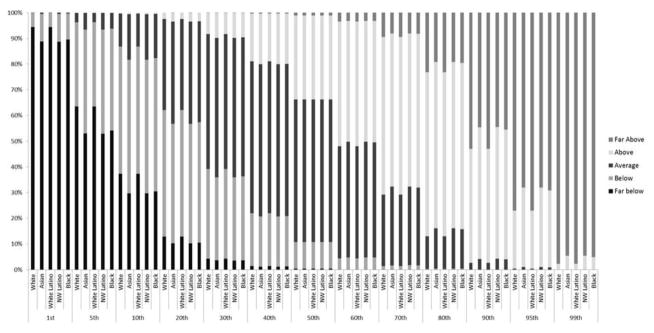

It is important to note that although Model 3 results point to possible inaccuracies in teachers’ perceptions of students’ overall literacy skills; they also suggest a high level of accuracy as well. To highlight the extent of accuracies and inaccuracies in teachers’ perceptions, Figure 1 presents predicted probabilities for the entire distribution of teachers’ perceptions by race/ethnicity and across a range of ability levels (based on percentiles). The diagonal bands represent changes in teachers’ perceptions from the lowest level of achievement (bottom 1 percentile) to the highest (99th percentile). At the lower end of the spectrum, students are generally rated as far below or below average, whereas at the higher end, students are generally rated as above or far above average. Although extreme ratings (far above and far below) are primarily saved for the lowest and highest performers (the bottom and top 5 percent, respectively), in general, there is close alignment between teachers’ perceptions and student ability. Within most percentile sections, however, small but notable differences between racial groups remain; the following analysis focuses on these differences.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probability Distribution for Teachers’ Perceptions of Language and literacy Skills by Race/Ethnicity and Student Performance

Note: Estimated using statistically significant coefficients (p < .05) from Table 3, Model 3.

5.2.3. Evaluating racial gaps

Table 4 results demonstrate the extent to which student (Model 1), teacher/classroom (Model 2), and school (Model 3) characteristics help explain racial gaps in teachers’ perceptions. In Model 1, I find significant gender differences in teachers’ ratings, but neither socioeconomic status nor age are significant predictors of teachers’ perceptions. Furthermore, accounting for student demographics has no substantive effect on the interaction coefficients. Model 2 results show that teachers’ race, but not education or age, is a significant predictor of teachers’ perceptions, such that Hispanic teachers, and to a lesser extent other race/ethnicity teachers, rate students higher on average than White teachers. In addition, I find that students in classrooms with more high ability peers are rated more poorly by teachers, yet accounting for teacher characteristics and classroom-level ability has no effect on racial gaps. Model 3 estimates show that students who attend schools that have a larger proportion of Hispanic, Black, or low income students, are in a town or rural area (vs. city), or are in the Midwest (vs. South) receive more positive literacy ratings, whereas attending a school with a larger proportion of Asian students is associated with less positive ratings. Accounting for school-level factors results in slight reductions in the interaction effects for non-White Latino students and Black students and a slight increase for Asian students, the general patterns remain.8

Table 4.

Three-Level Ordered Probit Coefficients and Standard Errors for Teachers’ Perceptions of Language and Literacy Skills Regressed on Students’ Race and Academic Performance with Student, Teacher, and School Level Covariates (ECLS-K 1998–99: 1st Grade, N = 10,740)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Student-Level | ||||||

| Asiana | .018 | (.085) | −.026 | (.086) | −.018 | (.091) |

| White Latino | .076 | (.085) | .031 | (.086) | −.054 | (.087) |

| Non-White Latino | .141 | (.084) | .079 | (.085) | −.045 | (.089) |

| Black | .066 | (.064) | .039 | (.067) | −.100 | (.077) |

| Literacy Score (standardized)b | 1.846 *** | (.032) | 1.863 *** | (.032) | 1.865*** | (.031) |

| Asian x Literacy Score | −.173 * | (.085) | −.174 * | (.084) | −.185* | (.081) |

| White Latino x Literacy Score | −.115 | (.084) | −.101 | (.084) | −.079 | (.081) |

| Non-White Latino x Literacy Score | −.168 * | (.077) | −.150 * | (.076) | −.143* | (.073) |

| Black x Literacy Score | −.148 * | (.058) | −.149 * | (.058) | −.138* | (.056) |

| Male | −.129 ** | (.043) | −.130 ** | (.042) | −.133** | (.041) |

| Socioeconomic Status | −.008 | (.031) | .010 | (.031) | .041 | (.031) |

| Age (in months) | .002 | (.005) | .003 | (.005) | .003 | (.005) |

| Teacher/Classroom-Level | ||||||

| Black | .102 | (.087) | −.095 | (.089) | ||

| Hispanic | .506 *** | (.104) | .315** | (.105) | ||

| Other Race | .236 * | (.123) | .269* | (.125) | ||

| Bachelor’s | −.039 | (.054) | −.020 | (.054) | ||

| Master’s | −.049 | (.053) | −.041 | (.051) | ||

| Doctorate/Education Specialist | −.082 | (.090) | −.081 | (.087) | ||

| Age | .000 | (.002) | .001 | (.002) | ||

| % Reading Below Grade Level | .004 *** | (.001) | .003** | (.001) | ||

| % Reading Above Grade Level | −.002 * | (.001) | −.001 | (.001) | ||

| School-Level | ||||||

| Percent Poverty | .002** | (.001) | ||||

| Percent Asian | −.006** | (.002) | ||||

| Percent Hispanic | .008*** | (.001) | ||||

| Percent Black | .007*** | (.001) | ||||

| Public School | .111 | (.062) | ||||

| Suburb | −.050 | (.050) | ||||

| Town/Rural | .142* | (.058) | ||||

| Northeast | .115 | (.061) | ||||

| Midwest | .140* | (.056) | ||||

| West | .082 | (.066) | ||||

| Threshold 1 | −2.698 *** | (.042) | −2.707 *** | (.042) | −2.726*** | (.042) |

| Threshold 2 | −1.250 *** | (.032) | −1.260 *** | (.032) | −1.274*** | (.032) |

| Threshold 3 | .413 *** | (.030) | .405 *** | (.030) | .398*** | (.030) |

| Threshold 4 | 2.284 *** | (.037) | 2.277 *** | (.037) | 2.277*** | (.037) |

| Variance Component | ||||||

| Classroom Level (τ00) | .479 | (.021) | .485 | (.021) | .479 | (.021) |

| School Level (τ00) | .455 | (.023) | .440 | (.023) | .405 | (.023) |

| Model Statistics | ||||||

| Deviance | 42,438 | 42,163 | 41,986 | |||

| AIC | 42,496 | 42,257 | 42,120 | |||

Includes Pacific Islanders.

Instrumented using previous year’s reading score.

Note: References categories are White (students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ race/ethnicity), Bachelor’s degree plus graduate coursework (educational attainment), City (locale), and South (region). All variables except student’s race and literacy scores are grand mean centered.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

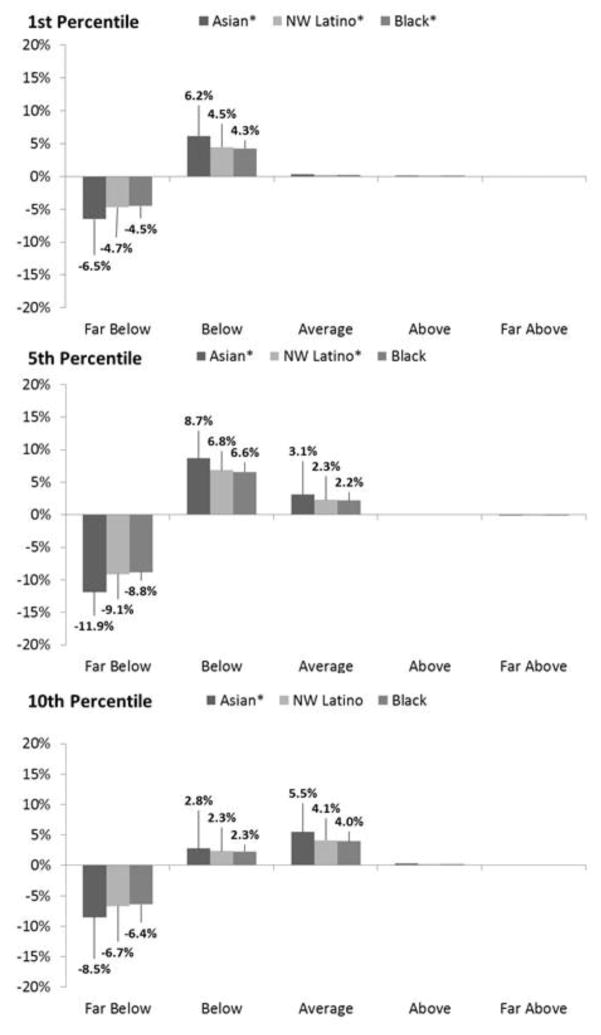

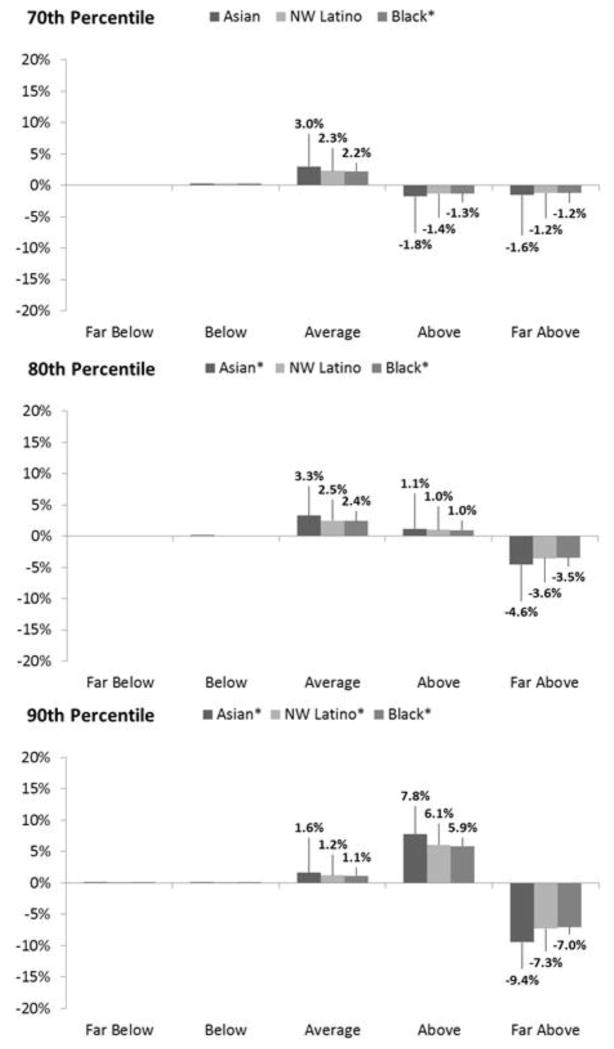

What are the extents of these inaccuracies? In Figure 2, I present racial differences in the predicted probability of overall literacy ratings for below average performers based on estimates from Table 4, Model 3. For students at the bottom of the ability distribution (1st percentile), model estimates translate to sizable gaps that favor minority students, such that Asian, non-White Latino, and Black students between 4 and 6 percentage points less likely than White students to be rated far below average. Although percentage point gaps increase slightly at the 5th percentile, only the gaps between Asian and White students and between non-White Latino and White students remain statistically significant. By the 10th percentile, Asian students are the only ones who continue to be rated less negatively than their White peers. It appears that, on average, very low achieving minority students are more likely to be given less negative ratings (e.g., ratings of average or below average as opposed to far below average) than similar performing white students.

Figure 2.

Differences in Predicted Probabilities of Teachers’ Literacy Ratings for Low Performing Students

Note: Compared to white students. Estimated using statistically significant coefficients (p< .05) from Table 4, Model 3 with covariates grand mean centered. Only gaps ≥1% are noted. * p < .05 (two tailed).

Predicted probabilities for above average performers demonstrate a different pattern (see Figure 3). At the 70th percentile, I find statistically significant Black-White differences (at p < .05) in the probability being rated average as opposed to above or far above average. By the 80th percentile, significant gaps favoring white students over Asian and non-White Latino students also emerge, such that Asian, non-White Latino, and Black students bordering the top quintile are between 3 and 5 percentage points less likely than similarly situated white peers to be rated as far above average. Among the highest performers (90th percentile), minority students are between 7 and 9 percentage points less likely to be rated far above average. In contrast to low performers, high performing minority students are more likely to receive ratings that are less positive (one to two categories lower) than their white peers.

Figure 3.

Differences in Predicted Probabilities of Teachers’ Literacy Ratings for High Performing Students

Note: Compared to white students. Estimated using statistically significant coefficients (p < .05) from Table 4, Model 3 with covariates grand mean centered. Only gaps ≥1 % are noted. * p < .05 (two tailed).

These findings highlight small, but persistent racial gaps in teacher perceptions of overall literacy skills. Although I find racial gaps both at the lower and upper end of the distribution of cognitive ability (as measured by IRT literacy test), the more positive perceptions experienced by minority students relative to whites appears to be isolated to the lowest performers (bottom 10 percent). In contrast, I find evidence of significant racial gaps that favor white students over their non-White peers among the top third of performers. Altogether, these results suggest that inaccuracies in teacher perceptions may in fact be related to students’ race/ethnicity. It could also be the case, however, that teachers consider multiple factors when rating overall skills, including some that may not overlap perfectly with literacy tests scores.

To test this supposition, I estimated three additional models. The first model includes teachers’ ARS literacy ratings as an additional covariate. Although Ready and Wright (2011) find some inaccuracies in teachers’ ARS literacy ratings, the comprehensive nature of this assessment makes it a useful indicator of other possibly unmeasured literacy skills. If teachers’ overall perceptions are truly a reflection of student ability, accounting for this comprehensive literacy assessment should explain most, if not all of the remaining racial gaps. Another possibility is that teachers’ overall literacy ratings may also be reflections of the ways students approach (or are perceived to approach) their academic learning.

Results from Table 5, Model 1 show that ARS scores are positively associated with teachers’ ratings of students’ overall literacy skills. I also find that ARS scores matter for racial gaps in teacher perceptions, though not always in the ways that one would expect. After accounting for ARS ratings, the interaction term for Asian students is not only substantially reduces but also becomes statistically insignificant, suggesting that ARS scores explain much if not all of the remaining Asian-White gap in teacher perceptions. In contrast, accounting for ARS scores actually increases the magnitude of racial gaps for non-White Latino and Black students.

Table 5.

Three-Level Ordered Probit Coefficients and Standard Errors for Teachers’ Perceptions of Language and Literacy Skills Regressed on Students’ Race and Academic Performance with Controls for Teacher and Parent Assessments (ECLS-K 1998–99: 1st Grade, N = 10,740)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Student-Level | ||||||

| Asiana | .073 | (.095) | −.101 | (.086) | −.012 | (.090) |

| White Latino | −.068 | (.091) | −.068 | (.083) | −.052 | (.087) |

| Non-White Latino | .000 | (.093) | −.059 | (.085) | −.040 | (.089) |

| Black | −.048 | (.080) | −.032 | (.073) | −.102 | (.076) |

| Literacy Score (standardized)b | 1.368 *** | (.042) | 1.767 *** | (.031) | 1.859 *** | (.031) |

| Asian x Literacy Score | −.104 | (.084) | −.141 | (.076) | −.180 * | (.080) |

| White Latino x Literacy Score | −.109 | (.085) | −.058 | (.076) | −.080 | (.080) |

| Non-White Latino x Literacy Score | −.184 * | (.077) | −.149 * | (.069) | −.148 * | (.073) |

| Black x Literacy Score | −.211 *** | (.059) | −.176 ** | (.053) | −.140 * | (.056) |

| ARS Literacy Assessment Score | 1.372 *** | (.042) | ||||

| Approaches to Learning (Teacher) | .550 *** | (.034) | ||||

| Approaches to Learning (Parent) | .122 ** | (.043) | ||||

| Threshold 1 | −3.872 *** | (.046) | −2.984 *** | (.041) | −2.743 *** | (.042) |

| Threshold 2 | −1.727 *** | (.035) | −1.373 *** | (.031) | −1.279 *** | (.032) |

| Threshold 3 | .687 *** | (.033) | .473 *** | (.029) | .403 *** | (.030) |

| Threshold 4 | 3.126 *** | (.039) | 2.431 *** | (.036) | 2.286 *** | (.037) |

| Variance Component | ||||||

| Classroom Level (τ00) | .639 | (.022) | .459 | (.021) | .481 | (.021) |

| School Level (τ00) | .335 | (.030) | .356 | (.023) | .401 | (.023) |

| Model Statistics | ||||||

| Deviance | 34,426 | 39,464 | 41,781 | |||

| AIC | 34,564 | 39,602 | 41,919 | |||

Includes Pacific Islanders.

Instrumented using previous year’s reading score.

Note: Models include student, teacher/classroom, and school-level controls as noted in Table 4, Model 3. All variables except student’s race and literacy scores are grand mean centered.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

In Models 2 and 3, I examine the impact of teachers’ ratings Approaches to Learning (Model 2) and parents’ ratings of Approaches to Learning (Model 3) on racial gaps. Results show that both measures are also positively associated with teachers’ overall literacy ratings. Their impact on racial gaps, however, appear to be modest at best. For example, although controlling for teachers’ perceptions of Approaches to Learning reduces the interaction term for Asian students and increases the term for Black students, racial differences in the predicted probabilities produced from this model—except for the now marginally significant Asian-White gap—do not differ much from those presented in Figures 2 and 3. In addition, parents’ perceptions of Approaches to Learning appear to have no bearing on the remaining racial gaps in teacher perceptions.9

6. Discussion and conclusion

What do these findings tell us about the relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions of overall literacy skills? I find demonstrable differences in the distributions of teachers’ perceptions (far below average to far above average) across racial groups, such that White, Asian, and White Latino students receive above average ratings which much greater frequency than do non-White Latino and Black students. Consistent with previous research, multivariate results demonstrate close alignment between teacher perceptions and students’ cognitive skills (as measured by literacy test scores). However, I also find significant racial gaps in teachers’ ratings of students at the lower and upper ends of the test score distribution.

One possible takeaway of this study is that students’ literacy scores explain much of the racial/ethnic differences in teachers’ assessments. Considering the amount of training and testing individuals must undertake to become teachers, the level of accuracy with which teachers are able to identify students’ skills comes as no surprise. Indeed, teachers are, by and large, regarded as the best source for information on student performance and adjustment. As a result, teachers’ perceptions and assessments carry tremendous weight for a variety of student experiences and outcomes.

Interestingly, these very same factors—sentiments regarding the accuracy of teachers’ assessments and the authority they hold—point to another possible takeaway, namely, that despite accounting for literacy test scores, significant racial differences in teachers’ overall literacy ratings remain. The fact that these gaps emerge so early in students’ educational careers is especially striking. Given the importance of teacher perceptions for both the student-teacher relationship and student outcomes, this finding will likely garner broad interest, especially among educators and researchers attuned to issues of social inequality. This finding also has important implications for our understanding of racial achievement gaps and racial differences in academic growth, both concerns which motivate this study.

In my evaluation of predicted probabilities, important patterns emerge. I find significant racial gaps in teacher perceptions among both low and high performing students. For some very low achieving minority students, these gaps translate to a slight advantage in teacher perceptions over similar performing Whites. Among higher performers, however, minority students are less positively perceived than their white peers. Interestingly, although these patterns hold for Asian, non-White Latino, and Black students, results showed no significant differences in teachers’ ratings of White Latino students compared to their White, non-Latino peers.

This study also considered other performance related factors, including skill specific assessments and perceptions of students’ learning behaviors, which could contribute to teachers’ overall assessments of students’ literacy skills. If racial gaps in teacher perceptions are primarily driven by unmeasured error in students’ cognitive literacy skills or influenced by perceptions of students’ learning behaviors, accounting for these factors should explain all remaining racial gaps. Results show that all three measures (ARS literacy scores, teacher ratings of Approaches to Learning, and parent ratings of Approaches to Learning) are positively associated with teachers’ perceptions of overall literacy skills; however, only teacher-derived measures have any real impact on racial gaps, and not always in the manner expected.

Specifically, I find that ARS literacy scores and teacher perceptions of Approaches to Learning explain the Asian-White gap in teacher perceptions, but do not reduce racial gaps between Black and White students and non-White Latino and White students. In fact, it appears that accounting for teacher perceptions of Approaches to Learning may actually magnify the Black-White gap in teacher perceptions at the ends of the performance distribution. Although results provide some support for the idea that teachers may be including other aspects of student learning and potential into account, they also demonstrate how race/ethnicity continues to matter for teachers’ assessments of student ability. On the whole, I find consistent support for Hypothesis 3, which suggests that the relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions is moderated by students’ cognitive ability.

6.1. Limitations

Before discussing the implications of these findings, there are several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, while regression analysis is useful for estimating the extent of racial differences, I am unable to make a causal link between students’ race/ethnicity and teacher perceptions. Thus, I cannot definitively prove that a student’s race/ethnicity or deficit thinking actually causes teachers to rate high achieving Black and non-White Latino students lower than high-achieving White students. I do, however, perform a number of robustness checks that attempt to measure these gaps against indicators of students’ actual abilities. Second, although I find that school characteristics are important for understanding differences in teachers’ perceptions of students, I do not discern exactly why this is the case. Given that the accuracy of teachers’ perceptions may be influenced by contextual factors (Ready and Wright, 2011), future research would benefit from analyses detailing which contextual factors are most closely related to racial differences in teachers’ perceptions. Last, although self-fulfilling prophecies are relevant to the discussion of teachers’ perceptions, I do not address them directly in my analyses.

6.2. Implications

This performance perception paradox has significant implications for the academic growth and success of high achieving and gifted minority students. Teachers that underestimate the overall abilities of high performing Black and non-White Latino students may be less likely to place these students in upper-level ability groups or to recommend them for gifted education programs. Having less positive perceptions of some high-performing minority students may also shape teachers’ expectations of and interaction with these students in ways that may limit them from performing to their full potential. I cannot say with certainty that deficit thinking is the cause of these patterns. It is striking, however, that the students most likely to receive poorer ratings from teachers relative to Whites are members of racial/ethnic groups most closely aligned with and plagued by deficit thinking, but whose test performance indicates a level of proficiency that defies these stereotypes.

Another major finding of this study is that low performing Asian, non-White Latino, and Black students are, on average, more positively perceived than similar performing White students. Considering the prevalence of negative stereotypes related to the academic potential of Black and Latino students, how do we reconcile this finding? It could be that if teachers possess higher expectations of white students than non-White students, conscious or subconscious, they may be more critical of poor performing White students than they are of non-White students. As another plausible explanation, increasing awareness around issues of equity in education, as well as increasing racial sensitivity and paranoia (Jackson, 2008) may encourage or compel teachers to exhibit more restraint in their use of extreme labels, such as far below average, when rating low achieving minority students. While my findings suggest that some minority students benefit from more positive perceptions, it is also possible that these “benefits” are actually an artifact of ratings that do not reflect teachers’ true sentiments.

This research makes several important contributions. First, I use an interaction effects model to demonstrate how academic ability impacts the relationship between students’ race/ethnicity and teachers’ perceptions. While the main effects model gives the impression that racial gaps in teachers’ perceptions are entirely driven by differences in academic ability, the interaction effects model shows how cognitive ability (as measured by literacy test scores) not only mediates, but also moderates this relationship. In the interaction effects mode, racial gaps emerge both at the bottom and the top of the performance distribution, serving as an important lesson for quantitative scholars interested in educational equity. If our efforts to understand racial gaps do not include an acknowledgement of possible within group variation, we may rule out or “explain away” race even as it continues to have real world implications (Bonilla-Silva, 2006). In this case, accounting for academic ability closed racial gaps in the fixed effects model masked the racial gaps present at the top and the bottom of the performance distribution.

Second, recent scholarship on race/ethnicity and educational inequality has largely focused on academically unprepared and lower performing minority students, which is problematic because racial achievement gaps are not only shaped by students at the bottom of the performance distribution but also by those near the top. Undoubtedly, high achieving minority students benefit in many ways from their academic success and from having teacher who motivate them to excel. However, this study indicates that high achieving minority students are also more likely to be underestimated by teachers than similar performing white students. These findings challenge the commonly held belief that academic excellence can nullify the negative influence of minority status on external appraisals (Foster, 1990; Morris, 2005a; Tyson, 2003). If the cognitive abilities of high achieving minority students hold less value in teachers’ overall perceptions, they may also hold less value during decisions concerning academic placements, access to enrichment opportunities, and the distribution of resources and support. Focusing more attention on the early educational experiences of high achieving minority students and identifying factors relevant to their academic and social growth will bring greater attention to this understudied population.

In first grade, students are typically unaware of the ways their own sociodemographic characteristics influence their day-to-day experiences. Yet, evidence suggests that these factors already play a role in teachers’ perceptions in ways that can influence teacher–student interaction, academic placements, and learning trajectories. Early interventions focused on improving teachers’ abilities to objectively assess student knowledge may be one way we can improve minority student success. But if deficit thinking is influential in informing these assessments, even to a small extent, developing teachers’ assessment skills may not be enough to address racial differences in teacher perceptions. The most effective interventions will likely be those that not only increase assessment skills, but also address deficit thinking and racial stereotypes by encouraging teachers, through regular reflection, to think about how their own assumptions impact their actions and day-to-day decision-making.

Highlights.

Examines racial differences in teachers’ perceptions of first grade students’ overall literacy skills.

Results demonstrate significant racial gaps in teachers’ perceptions of Black, non-White Latino, and Asian students (compared to White students).

Cognitive literacy skills explain most racial differences, but also moderate remaining racial gaps.

Among low performers, teacher perceptions favor some minority students, but among high performers, the reverse is true.

Teacher ratings from skill specific assessments explain remaining racial gaps for Asian students, but not for Black or non-White Latino students.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Ford Foundation Fellowship through The National Academies, by a grant from the American Educational Research Association which receives funds for its Grants Program from the National Science Foundation under NSF Grant #DRL-0941014, and by Grant, 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Opinions reflect those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agencies.

Thanks to Brian Powell, Matthew Hughey, Frank Worrell, and Donald Shaffer for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

In addition to being the first year of compulsory schooling, first grade is an ideal time to study racial variation in teachers’ perceptions because student are generally excited about learning and less likely to be influenced by peers (Tyson, 2002; Harris, 2006; Darling and Steinberg, 1997).

Because of evidence suggesting that teacher determined grades may be more susceptible to teacher bias than standardized tests (Alexander et al., 1987), the term cognitive ability refers to performance on externally administered assessments.

While age may be a factor, Jussim and Harber (2005) propose the vulnerability of students during transitional periods as a more likely explanation for this trend.

Rist (1970) notes the importance of similar factors (e.g. grooming) for decisions about reading ability group placements.

All sample sizes and weighted frequencies are rounded to the nearest ten as per Institute for Education Sciences (IES) policy for restricted data use.

According to Wooldridge, unlike traditional IV approaches, the multiple indicator IV solution does not require that the instrument be uncorrelated with other covariates in the model.

The cmp program fits seemingly unrelated maximum likelihood regression models that are consistent with recursive systems (Roodman, 2011).

I replicated these analyses using both kindergarten literacy scores and kindergarten teachers’ ARS literacy ratings as instruments for first grade test scores. Although doing this tempered all three significant interaction effects, the general patterns remained.

Additional models [available upon request] controlling for parents’ ratings of self-control and impulsiveness garnered similar results.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Horsey CS. From first grade forward: Early foundations of high school dropout. Sociology of Education. 1997;70:87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Thompson MS. School performance, status relations, and the structure of sentiment: Bringing the teacher back in. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:665–682. [Google Scholar]

- Bates LA, Glick JE. Does it matter if teachers and schools match the student? Racial and ethnic disparities in problem behaviors. Social Science Research. 2013;42:1180–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudson TG, Preckle F. Teachers’ implicit personality theories about the gifted: An experimental approach. School Psychology Quarterly. 2013;28:37–46. doi: 10.1037/spq0000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. Landham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brattesani KA, Weinstein RS, Marshall HH. Student perceptions of differential teacher treatment as moderators of teacher expectation effects. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1984;76:236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy JE, Good TL. Teachers’ communication of differential expectations for children’s classroom performance: Some behavioral data. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1970;61:365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Peisner-Feinberg E, Pianta R, Howes C. Development of academic skills from preschool through second grade: Family and classroom predictors of developmental trajectories. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40:415–436. [Google Scholar]

- Burkam DT, LoGerfo L, Ready D, Lee VE. The differential effects of repeating kindergarten. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) 2007;12:103–136. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein ND, Cabello B. Preparing teachers to work with culturally diverse students: a teacher education model. Journal of Teacher Education. 1989;40:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chaikin AL, Sigler E, Derlega VJ. Nonverbal mediators of teacher expectancy effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1974;30:144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chang DF, Demyan AL. Teachers’ stereotypes of Asian, Black, and White students. School Psychology Quarterly. 2007;22:91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MR, Gallagher JJ, Foster A. Office of Educational Research and Improvement. U.S. Department of Education; 1994. Updated report on state policies related to the identification of gifted students. [Google Scholar]

- Condron DJ. Stratification and educational sorting: Explaining ascriptive inequalities in early childhood reading group placement. Social Problems. 2007;54:139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver RW, Mc Intyre DJ. Teachers’ perception of gifted students. Roeper Review. 1992;14:151–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Daniel N, Boston B. Educating able learners: Programs and promising practices. Design For Arts in Education. 1985;87:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, et al. Instruction, teacher-student relations, and math achievement trajectories in elementary school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102:407–417. doi: 10.1037/a0017762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis HA. Conceptualizing the role and influence of student-teacher relationships on children’s social and cognitive development. Educational Psychologist. 2003;38:207–234. [Google Scholar]

- Doll B. Children without friends: Implications for practice and policy. School Psychology Review. 1996;25:165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB. Black/White differences in school performance: The oppositional culture explanation. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34:107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB, Ainsworth JW, Qian Z. Rethinking the attitude-achievement paradox among Blacks. Sociology of Education. 2009;82:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB, Pribesh S. When race matters: Teachers’ evaluations of students’ classroom behavior. Sociology of Education. 2004;77:267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Easton-Brooks D, Davis A. Teacher qualification and the achievement gap in early primary grades. Education Policy Analysis Archives. 2009;17:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Alexander KL. Summer setback: Race, poverty, school composition, and mathematics achievement in the first two years of school. American Sociological Review. 1992;57:72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, Olson LS. Children, Schools, and Inequality. Westview Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Hayduk LA. Lasting effects of elementary school. Sociology of Education. 1988;61:147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas G. Racial disparities and discrimination in education: What do we know, how do we know it, and what do we need to know? The Teachers College Record. 2003;105:1119–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas G, Grobe RP, Sheehan D, Shuan Y. Cultural resources and school success: Gender, ethnicity, and poverty groups within an urban school district. American Sociological Review. 1990;55:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson AA. Bad Boys: Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity. University of Michigan Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson RF. Teachers’ perceptions and expectations and the Black-White test score gap. Urban Education. 2003;38:460–507. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DY. A Study of Achievement and Underachievement among Gifted, Potentially Gifted, and Average African-American Students. NRC/GT, University of Connecticut; 362 Fairfield Road, U-7, Storrs, CT 06269–2007: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DY. Reversing Underachievement Among Gifted Black Students: Promising Practices and Programs. Teachers College Press, Teachers College, Columbia University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DY. The underrepresentation of minority students in gifted education problems and promises in recruitment and retention. The Journal of Special Education. 1998;32:4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DY, Grantham T, Whiting G. Culturally and linguistically diverse students in gifted education: Recruitment and retention issues. Exceptional Children. 2008;74:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DY, Harris JJ, Tyson CA, Trotman MF. Beyond deficit thinking: Providing access for gifted African American students. Roeper Review. 2001;24:52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham S, Ogbu JU. Black students’ school success: Coping with the “burden of ‘acting White’”. The Urban Review. 1986;18:176–206. [Google Scholar]

- Foster M. The politics of race: Through the eyes of African-American teachers. Journal of Education. 1990;172:123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Good TL. Teacher expectations and student perceptions: A decade of research. Educational Leadership. 1981;38:415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Good TL, Brophy JE. Behavioral expression of teacher attitudes. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1972;63:617–624. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan MT. Teacher influences on students’ attachment to school. Sociology of Education. 2008;81:271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AL. I (don’t) hate school: Revisiting oppositional culture theory of Blacks’ resistance to schooling. Social Forces. 2006;85:797–834. [Google Scholar]

- Harris AL. Kids Don’t Want to Fail. Harvard University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harris AL, Robinson K. Schooling behaviors or prior skills? A cautionary tale of omitted variable bias within oppositional culture theory. Sociology of Education. 2007;80:139–157. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge RD, Coladarci T. Teacher-based judgments of academic achievement: A review of literature. Review of Educational Research. 1989;59:297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Wilson V. Further support for the developmental significance of the quality of the teacher–student relationship. Journal of School Psychology. 2001;39:289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine JJ. An analysis of the problem of disappearing Black educators. Elementary School Journal. 1988;88:503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine JJ. Black Students and School Failure: Policies, Practices, and Prescriptions. Greenwood Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SA. A Study of Teachers’ Perceptions of Youth Problems. Journal of Youth Studies. 2002;5:313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JL. Racial Paranoia: The Unintended Consequences of Political Correctness. New York: Basic Civitas; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Eccles JS. Teacher expectations: II. Construction and reflection of student achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:947–961. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Eccles JS. Naturally occurring interpersonal expectancies, Social Development. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA, US: 1995. pp. 74–108. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Eccles JS, Madon S. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 28. Academic Press; San Diego, CA, US: 1996. Social perception, social stereotypes, and teacher expectations: Accuracy and the quest for the powerful self-fulfilling prophecy; pp. 281–388. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Harber KD. Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: Knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:131–155. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnes FA, Whorton JE. Teacher certification and endorsement in gifted education: Past, present, and future. Gifted Child Quarterly. 1991;35:148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinfeld J. The relative importance of teachers and parents in the formation of Negro and White students’ academic self-concepts. Journal of Educational Research. 1972;65:211–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb KJ, Jussim L. Teacher expectations and underachieving gifted children. Roeper Review. 1994;17:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leacock E. The influences of teacher attitudes on children’s classroom performance: Case studies. In: Kathryn MB, editor. The Social Life of Children in a Changing Society. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 1982. pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Jussim L, Eccles J. In search of the powerful self-fulfilling prophecy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:791–809. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.4.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel HP, Marcus SI. The psychology of underachievement: differential diagnosis and differential treatment. New York: Wiley; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Masten WG, Plata M, Wenglar K, Thedford J. Acculturation and teacher ratings of Hispanic and Anglo-American students. Roeper Review. 1999;22:64–65. [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Evahn C, Kratzer L. High school underachievers: What do they achieve as adults? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McGrady PB, Reynolds JR. Racial mismatch in the classroom: Beyond Black-White differences. Sociology of Education. 2012;86:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- McKown C, Weinstein RS. Teacher expectations, classroom context, and the achievement gap. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46:235–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan BT, Hughes JN, Cavell TA. Teacher–student relationships as compensatory resources for aggressive children. Child Development. 2003;74:1145–1157. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisels SJ, Bickel DD, Nicholson J, Xue Y, Atkins-Burnett S. Trusting teachers’ judgments: A validity study of a curriculum-embedded performance assessment in kindergarten to grade 3. American Educational Research Journal. 2001;38:73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Menchaca M. Early racist discourses: The roots of de cit thinking. In: Valencia RR, editor. The Evolution of Deficit Thinking: Educational Thoughts and Practices. Falmer Press; New York: 1997. pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley C, Feldlaufer H, Eccles JS. Student/teacher relations and attitudes toward mathematics before and after the transition to junior high school. Child Development. 1989;60:981–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo GP, Mansfield EA, Miller RB. Liking or disliking the teacher: Student motivation, engagement and achievement. Evaluation & Research in Education. 2007;20:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Morris EW. From “middle class” to “trailer trash:” Teachers’ perceptions of White students in a predominately minority school. Sociology of Education. 2005a;78:99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Morris EW. “Tuck in that shirt!” Race, class, gender, and discipline in an urban school. Sociological Perspectives. 2005b;48:25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CB. Estimating achievement performance: A confirmation bias. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Oates GLSC. Teacher-student racial congruence, teacher perceptions, and test performance. Social Science Quarterly. 2003;84:508–525. [Google Scholar]

- Page R. Teachers’ perceptions of students: A link between classrooms, school cultures, and the social order. Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 1987;18:77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Partenio I, Taylor RL. The relationship of teacher ratings and IQ: A question of bias? School Psychology Review. 1985;14:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Adult–child relationship processes and early schooling. Early Education & Development. 1997;8:11–26. [Google Scholar]