Abstract

Background:

Primary dysmenorrhea with interferes in daily activities can have adverse effects on quality of life of women.

Objectives:

Regarding the use of herbal medicine, the aim of this study was to assess the effect of cinnamon on primary dysmenorrhea in a sample of Iranian female college students from Ilam University of Medical Sciences (west of Iran) during 2013-2014.

Patients and Methods:

In a randomized double-blind trial, 76 female student received placebo (n = 38, capsules containing starch, three times a day (TDS)) or cinnamon (n = 38, capsules containing 420 mg cinnamon, TDS) in 24 hours. Visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to determine the severity of pain and nausea. Vomiting and menstrual bleeding were assessed by counting the number of saturated pads. The parameters were recorded in the group during the first 72 hours of the cycle.

Results:

The mean amount of menstrual bleeding in the cinnamon group was significantly lower than the placebo group (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively). The mean pain severity score in the cinnamon group was less than the placebo group at various intervals (4.1 ± 0.5 vs. 6.1 ± 0.4 at 24 hours, 3.2 ± 0.6 vs. 6.1 ± 0.4 at 48 hours, and 1.8 ± 0.4 vs. 4.0 ± 0.3 at 72 hours, respectively) (P < 0.001). The mean severity of nausea and the frequencies of vomiting significantly decreased in the cinnamon group compared with the placebo group at various intervals (P < 0.001, P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Regarding the significant effect of cinnamon on reduction of pain, menstrual bleeding, nausea and vomiting with primary dysmenorrhea without side effects, it can be regarded as a safe and effective treatment for dysmenorrhea in young women.

Keywords: Herbal Medicine, Complementary Therapies, Pain, Nausea, Vomiting

1. Background

Primary dysmenorrhea is defined as a cyclic and painful cramps pelvic, occurring just before or during menstruation which deranges daily activities (1). Primary dysmenorrhea is one of the most common gynecologic disorders in young women which may affect more than half of menstruating women (2-4). Prostaglandin production by ovulation is the main cause of primary dysmenorrhea (5, 6). Digestive disorders including nausea, vomiting and diarrhea are the symptoms associated with primary dysmenorrhea, which are known due to intestinal spasms during menstruation (7). The prevalence of dysmenorrhea in different populations is 50 - 90% and in Iran it is 74 - 86.1% (8, 9). Primary dysmenorrhea is a common cause of absenteeism from work, education, or referral to physician, which may lead to decreased efficacy of occupation and education. Although dysmenorrhea is not life threatening, it could have adverse effects on quality of life (10).

In the USA, the annual economic loss of dysmenorrhea is 600 million working hours and two billion dollars (11, 12). In a study of 664 school students in Egypt, about 75% of the students had dysmenorrhea, rated scanty in 55.3%, moderate in 30%, and severe in 14.7% (13). In a study on female students, 42% had a sessions absence from teaching or daily activities due to dysmenorrhea. The study suggested that 50% of girls believed that dysmenorrhea impairs daily activities (14). Several methods such as drugs (including oral contraceptive pills (OCP) consumption and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), nonpharmacological treatments (including exercise, heat therapy, acupuncture, and trans-electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)), dietary supplements (vitamins E, B, C, and Ca, Mg) and medicinal herbal have been used for treatment of primary dysmenorrhea (15, 16). Synthetic drugs, especially in long-term administration, have side effects. Nausea, stomach irritation, ulcers, renal papillary necrosis, and decreased renal blood flow are the side effects of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors (14). On the other hand, most of the young women have no tendency to use hormones to reduce pain. Today, regarding the effects of chemical drugs and the usage of herbal medicine, as well as alternative and complementary therapies in treatment of diseases, many interested researchers have been drawn to this area. One of these herbal medicines and alternative therapies is cinnamon which has many applications in medicine, but has not been sufficiently documented.

2. Objectives

Despite of its high prevalence, dysmenorrhea has not been managed effectively. Therefore, due to the lack of comprehensive studies for treatment of digestive disorders accompanied with dysmenorrhea in Iran and because of the importance of economic and social aspects of dysmenorrhea and acceptability and availability of traditional medicines, the aim of this study was to assess the effects of cinnamon on menstrual bleeding and systemic symptoms (nausea and vomiting) with primary dysmenorrhea in a sample of Iranian female college students from Ilam University of Medical Sciences (west of Iran) during 2013 - 2014.

3. Patients and Methods

This was a quasi-experimental study performed at Ilam University of Medical Sciences during 2013 - 2014. The statistical population included all female college students living in governmental dormitories. The sample size was calculated using the information obtained from a pilot study with 10 patients and Equation 1:

| (1) |

Z1 = 95% = 1.96

Z2 = 80% = 0.84 (test power)

S = an estimate of the standard deviation of visual analogue scale (VAS) in the groups; 1.67 was obtained in a pilot study.

d = the minimum of the mean difference of VAS between the groups which showed a significant difference and was obtained 1.1.

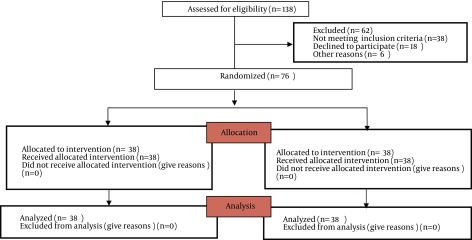

A simple random sampling design was used (Figure 1). After getting a written permission from the School of Nursing and Midwifery, the researcher visited the students of dormitories and the study objectives were explained to them. Thereafter, from the interested students who had the inclusion criteria using simple random sampling of the number of the students, the residences were divided into two groups of placebo and cinnamon.

Figure 1. Flow Chart.

In a randomized double-blind trial, 76 female students received placebo (capsules contain starch three times a day (TDS), n = 38) or cinnamon (capsules containing 420 mg cinnamon, two capsules TDS, n = 38) in 24 hours during the first three days of the menstrual cycle. The order of use and the shapes of capsules were similar in the groups. The inclusion criteria were age 18 - 30, regular menstrual cycles, lack of chronic diseases, moderate primary dysmenorrhea, digestive disorder (nausea or vomiting) with primary dysmenorrhea, lack of pelvic inflammatory diseases, tumor or fibroma, lack of recent stressors, and BMI 19 - 26. The exclusion criteria were the use of oral contraceptive pill (OCP), receiving analgesics during the study period, and medical or herbal allergy. We used VAS to determine the severity of pain and nausea. The number of times of vomiting was counted and menstrual bleeding was assessed by counting the number of saturated pads. Pain intensity, nausea, vomiting and menstrual bleeding were monitored in the groups during the first 72 hours of cycle (first, second, and third days of menstruation). The pain severity was assessed in 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16, 24, 48 and 72 hours after the intervention. The nausea severity, vomiting and the amount of menstrual bleeding were assessed in 24, 48, and 72 hours after the intervention. The female college students’ age, menarche age, length of menstrual cycle, level and duration of pain, and age of dysmenorrhea were recorded.

3.1. Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Ilam University of Medical Sciences, Ilam, Iran, and informed consents were obtained from all the participants (ethical code/92/H/184, 13/Dec/2012). In addition, this study was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT2013122114668N2).

3.2. Validity and Reliability

VAS rating is a standard tool for evaluation of pain severity, rated from 0 to 10.0; 0 means no pain and 10 means the maximum pain in this scale. Regarding the severity of nausea, 0 means no nausea and 10 means the maximum nausea. To determine the validity of the questionnaire, content validity was used. The questionnaire was provided to 10 faculty members of Ilam University of Medical Sciences and was used after revision. To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha test was used. The reliability of the questionnaire was determined 0.89.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the statistical software SPSS, version 16. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL., USA). Descriptive statistics, independent t-test, chi-square test, repeated measurement, Friedman test, and Man-Whitney were performed to analyze the results. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

Baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. None of the 76 enrolled females was withdrawn for any reason. Samples characteristics were not different among the groups (P > 0.5) (Table 1). According to Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, data distribution was normal and we used the parametric methods (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Participants a.

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 38) | Cinnamon (n = 38) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 1.5 ± 21.3 | 1.1 ± 20.7 | 0.135 |

| Age of menarche, y | 0.8 ± 13.4 | 0.8 ± 13.3 | 0.116 |

| Cycle, d | 1.5 ± 27.8 | 1.5 ± 27.4 | 0.487 |

| Age of dysmenorrhea, y | 0.9 ± 14.6 | 0.5 ± 14.3 | 0.476 |

| Duration of bleeding, d | 6.1 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 6.3 | 0.090 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

b P > 0.05.

Table 2. Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test a.

| Parameters | K-S | P Value | Parameters | K-S | P Value | Parameters | K-S | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 0.796 | 0.555 | Pain 8 | 0.813 | 0.638 | Bleeding 24 | 0.629 | 0.429 |

| Age of menarche, y | 0.913 | 0.386 | Pain 16 | 0.504 | 0.368 | Bleeding 48 | 0.819 | 0.338 |

| Cycle, d | 0.657 | 0.486 | Pain 24 | 0.681 | 0.593 | Bleeding 72 | 0.749 | 0.628 |

| Age of dysmenorrhea, y | 0.589 | 0.674 | Pain 48 | 0.938 | 0.654 | Nausea | 0.563 | 0.364 |

| Duration of bleeding, d | 0.847 | 0.538 | Pain72 | 0.727 | 0.433 | Nausea 24 | 0.486 | 0.377 |

| Pain | 0.719 | 0.439 | Pain duration | 0.438 | 0.322 | Nausea 48 | 0.538 | 0.467 |

| Pain 1 | 0.691 | 0.518 | Duration 24 | 0.549 | 0.738 | Nausea 72 | 0.613 | 0.489 |

| Pain 2 | 0.739 | 0.345 | Duration 48 | 0.582 | 0.623 | Vomiting 24 | 0.764 | 0.513 |

| Pain 3 | 0.489 | 0.636 | Duration 72 | 0.648 | 0.389 | Vomiting 48 | 0.839 | 0.360 |

| Pain 4 | 0.949 | 0.421 | Bleeding | 0.864 | 0.512 | Vomiting 72 | 0.693 | 0.459 |

aAbbreviation: K-S, Kolmogorov–Smirnov.

Independent t-test showed that the mean pain severity score in the cinnamon group was less than the placebo group at various intervals (P < 0.001) (Table 3). The mean duration of pain in the cinnamon group was significantly less than the placebo group at various intervals (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Repeated measurement analysis showed that the mean pain score in the cinnamon group (P < 0.001) and the placebo group (P = 0.001) were significantly different in various intervals. The mean amount of menstrual bleeding in the cinnamon group was significantly lower than the placebo group at various intervals (P < 0.05, P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 3. Outcome of Severity of Pain Between Groupsa.

| Pain Score by vas at Various Intervals, h | Placebo (n = 38) | Cinnamon (n = 38) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | 1 ± 7.5 | 1 ± 7.4 | 0.569 b |

| 1 h After intervention | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 0.00 c |

| 2 h After intervention | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 6.8 ± 0.7 | 0.00 c |

| 3 h After intervention | 6.8 ± 0.7 | 6.6 ± 0.4 | 0.00 c |

| 4 h After intervention | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 0.00 c |

| 8 h After intervention | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 0.00 c |

| 16 h After intervention | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 0.00 c |

| 24 h After intervention | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 0.00 c |

| 48 h After intervention | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 0.00 c |

| 72 h After intervention | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 0.00 c |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

b P > 0.05.

c P < 0.001.

Table 4. Outcome of Duration of Pain Between Groupsa.

| Duration of Pain, hour | Placebo (n = 38) | Cinnamon (n = 38) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | 2.3 ± 26.5 | 2.3 ± 27.2 | 0.359 b |

| 24 h After intervention | 25.2 ± 1.9 | 16.5 ± 1.6 | 0.00 c |

| 48 h After intervention | 21.2 ± 1.5 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 0.00 c |

| 72 h After intervention | 18.7 ± 1.3 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 0.00 c |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

b P > 0.05.

c P < 0.001.

Table 5. Outcome of the Amount of Menstrual Bleeding Between Groups a.

| Amount of Menstrual Bleeding (Number of Used Pad) | Placebo (n = 38) | Cinnamon (n = 38) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of menstrual bleeding before of treatment | |||

| Scanty (1 pad) | 3 (7.8) | 4 (10.5) | 0.251 b |

| Average (2-3 pads) | 23 (60.5) | 22 (57.8) | 0.181 b |

| Excessive (≥ 4 pads) | 12 (31.5) | 12 (31.5) | 0.274 b |

| 24 h After intervention | |||

| Scanty (1 pad) | 4 (10.5) | 7 (18.4) | 0.032 c |

| Average (2-3 pads) | 23 (60.5) | 25 (65.7) | 0.061 b |

| Excessive (≥ 4 pads) | 11 (28.9) | 6 (15.7) | 0.037 c |

| 48 h After intervention | |||

| Scanty (1 pad) | 6 (15.7) | 17 (44.7) | 0.012 c |

| Average (2-3 pads) | 23 (60.5) | 20 (52.6) | 0.031 c |

| Excessive (≥ 4 pads) | 9 (23.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.00 d |

| 72 h After intervention | |||

| Scanty (1 pad) | 11 (18.4) | 27 (71.05) | 0.00 d |

| Average (2-3 pads) | 23 (60.5) | 11 (28.9) | 0.00 d |

| Excessive (≥ 4 pads) | 3 (7.8) | 0 (0.00) | 0.00 d |

a Values are presented as No. (%).

b P > 0.05.

c P < 0.05.

d P < 0.001.

According to Friedman’s test, the amount of menstrual bleeding in the cinnamon group was significantly different at various intervals (P < 0.001) and not significantly different in the placebo group at various intervals (P = 0.21). The mean severity of nausea significantly decreased in the cinnamon group compared with the placebo group at various intervals (P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively) (Table 6). Repeated measurement test showed that the mean nausea score in the cinnamon group (P < 0.001) and the placebo group (P = 0.03) were significantly different in various intervals. The frequencies of vomiting in the cinnamon group were less than the placebo group at various intervals (P < 0.001, P < 0.05) (Table 6). The frequencies of vomiting in the cinnamon group (P < 0.001) and the placebo group (P = 0.04) were significantly different in various intervals.

Table 6. Outcome of Severity of Nausea and Vomiting Between Groups a, b.

| Nausea Score by VAS at Various Intervals, h | Placebo (n = 38) | Cinnamon (n = 38) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea score before of treatment | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 5.6 ± 1.8 | 0.09 |

| 24 h After intervention | 5.5 ± 1.9 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 0.01 c |

| 48 h After intervention | 4.7 ± 2.2 | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 0.00 d |

| 72 h After intervention | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 0.00 d |

| Number of vomiting | |||

| Number of vomiting before of treatment | |||

| non | 25 (65.7) | 26 (68.4) | 0.06e |

| 1-2 | 11 (28.9) | 10 (26.3) | 0.18e |

| ≥ 3 | 2 (5.2) | 2 (5.2) | 0.08e |

| 24 h After intervention | |||

| non | 26 (68.4) | 32 84.2) | 0.01 c |

| 1-2 | 10 (26.3%) | 5 (13.1) | 0.00 d |

| ≥ 3 | 2 (5.2%) | 1 (2.6) | 0.04 c |

| 48 h After intervention | |||

| non | 29 (76.3) | 36 (94.7) | 0.00 d |

| 1-2 | 7 (18.4) | 2 (5.2) | 0.00 d |

| ≥ 3 | 2 (5.2) | 0 (0.00) | 0.00 d |

| 72 h After intervention | |||

| non | 31 (81.5) | 38 (100) | 0.00 d |

| 1-2 | 7 (18.4) | 0 (0.00) | 0.00 d |

| ≥ 3 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0.00 |

aAbbreviation: VAS, Visual analogue scale.

bValues are presented as mean ± SD or No. (%).

c P < 0.05.

d P < 0.001.

eP > 0.05.

5. Discussion

Our results suggested that cinnamon significantly reduced pain, the amount of menstrual bleeding, nausea and vomiting in female college students. Therefore, cinnamon improves the severity of primary dysmenorrhea. This finding was consistent with the previous studies on the effects of herbal medicines such as cumin (16) thymus vulgaris, Achillea millefolium (17), fennel (18), Matricaria recutita (19), Rosa damascena extract (20), aromatherapy massage and Zingiber officinale (1) in treatment of dysmenorrhea.

Dysmenorrhea is a common problem in young females (21, 22). Primary dysmenorrhea is caused by an increase in the synthesis and release of prostaglandins, particularly PGF2α from the uterine endometrium during the menstrual period. This prostaglandin in turn causes contraction of smooth muscles in many adjacent tissues. Uterine smooth muscle contractions cause colicky pains, spasmodic and labor-like pains in the lower abdomen and cause lower back pain which is a characteristic of dysmenorrhea. Furthermore, prostaglandin secretion causes smooth muscle contraction of gastric-intestinal tract, which can lead to nausea, vomiting and diarrhea (7, 23-27). Today in herbal medicine, numerous benefits have been found. Herbal medicines reduce the level of prostaglandins, have nitric oxide modulation effects, increase the levels of beta-endorphin, block calcium channels and improve circulation; thus, are effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhea (28-30). Cinnamon is one of the oldest and most traditional herbal medicines. Cinnamon is a member of the Lauraceae family, which has been widely used as a spice for thousands of years to improve the taste of foods and drinks. Indications of cinnamon in medicine include diarrhea treatment, as an astringent, germicide, antispasmodic, dyspeptic complaints, for chronic bronchitis, treatment of impotence, frigidity, dyspnea, inflammation of eye, leukorrhea, vaginitis, rheumatism, and neuralgia, as well as wounds and toothaches, cold and flu; but, has not been sufficiently documented. The oil extracted of cinnamon has anti-inflammatory activity, as a treatment for dysmenorrhea and to stop bleeding. However, toxicology trials performed with high doses demonstrated that the oil of this plant stimulated the mucous membranes and instigated hematuria (1, 5).

The main component of the essential oil of cinnamon bar is cinnamaldehyde (55 - 57%) and eugenol (5 - 18%). Cinnamaldehyde has been reported to have an antispasmodic effect. In addition, eugenol can prevent the biosynthesis of prostaglandins and reduce inflammation. Cinnamon contains a variety of vitamins such as vitamin A, thiamin, riboflavin, and ascorbic acid (20). In adults and adolescents, 1.5 - 4 g daily of dried bark cinnamon can be used. In this study, we used a total dose of 2.52 g daily (in three divided doses), which was effective on primary dysmenorrhea and no side effects were found with this dose. On the other hand, this was the first clinical trial on the effects of cinnamon on menstrual bleeding and systemic symptoms including nausea and vomiting due to primary dysmenorrhea in female college students in Iran, which was the strength of this study. Some of the factors influencing pain intensity and other symptoms with primary dysmenorrhea such as culture, genetic and nutrition (20, 31) were uncontrollable, which were the weak points of this study.

In conclusion, this research suggested that cinnamon has a significant effect on reduction of pain, menstrual bleeding, nausea and vomiting due to primary dysmenorrhea, and with respect to no reported side effects, cinnamon can be regarded as a safe and effective treatment for primary dysmenorrhea.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ilam University of Medical Sciences, participants, coordinators and data reviewers who assisted in this study.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:Molouk Jaafarpour, Masoud Hatefi, Fatemeh Najafi, Javaher khajavikhan and Ali khani participated in the study design, data analysis, literature review, preparation and editing the manuscript.

Funding/Support:This study was supported by Ilam University of Medical Sciences (grant No. 913007/140).

References

- 1.Unsal A, Ayranci U, Tozun M, Arslan G, Calik E. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and its effect on quality of life among a group of female university students. Ups J Med Sci. 2010;115(2):138–45. doi: 10.3109/03009730903457218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marzouk TM, El-Nemer AM, Baraka HN. The effect of aromatherapy abdominal massage on alleviating menstrual pain in nursing students: a prospective randomized cross-over study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:742421. doi: 10.1155/2013/742421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozgoli G, Goli M, Moattar F. Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(2):129–32. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaidi SA, Khatoon K, Aslam K. Role of herbal medicine in Ussuruttams (Dysmenorrhoea). youth education and research trust. 2012;1(3):113–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Souza A, da Costa Mendieta M, Hohenberger G, Silva M, Ceolin T, Heck R. Menstrual cramps: A new therapeutic alternative care through medicinal plants. sci res. 2013;5(7):1106–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durain D. Primary dysmenorrhea: assessment and management update. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49(6):520–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harel Z. Dysmenorrhea in adolescents and young adults: etiology and management. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(6):363–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziaei S, Zakeri M, Kazemnejad A. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin E in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. BJOG. 2005;112(4):466–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drosdzol A, Skrzypulec V. [Dysmenorrhea in pediatric and adolescent gynaecology]. Ginekol Pol. 2008;79(7):499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.French L. Dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(2):285–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissman AM, Hartz AJ, Hansen MD, Johnson SR. The natural history of primary dysmenorrhoea: a longitudinal study. BJOG. 2004;111(4):345–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slap* G. Menstrual disorders in adolescence. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2003;17(1):75–92. doi: 10.1053/ybeog.2002.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Gilany AH, Badawi K, El-Fedawy S. Epidemiology of dysmenorrhoea among adolescent students in Mansoura, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(1-2):155–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):428–41. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230214.26638.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnard N, Scialli AR, Hurlock D, Bertron P. Diet and sex-hormone binding globulin, dysmenorrhea, and premenstrual symptoms. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2000;95(2):245–50. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hejazi SH, Amin GH, Mahmoudi M, Movaghar M. Comparison of herbal and chemical drugs on primary dysmenorrhea. J Nurs Midwifery Shahid Beheshti Univ Med Sci. 2002;12(42):54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doubova SV, Morales HR, Hernandez SF, del Carmen Martinez-Garcia M, de Cossio Ortiz MG, Soto MA, et al. Effect of a Psidii guajavae folium extract in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110(2):305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namavar Jahromi B, Tartifizadeh A, Khabnadideh S. Comparison of fennel and mefenamic acid for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2003;80(2):153–7. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1548–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bani S, Hasanpour S, Mousavi Z, Mostafa Garehbaghi P, Gojazadeh M. The Effect of Rosa Damascena Extract on Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Double-blind Cross-over Clinical Trial. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(1) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.14643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeraati F, Shobeiri F, Nazari M, Araghchian M, Bekhradi R. Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of herbal drugs (fennelin and vitagnus) and mefenamic acid in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19(6):581–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindh I, Ellstrom AA, Milsom I. The effect of combined oral contraceptives and age on dysmenorrhoea: an epidemiological study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(3):676–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee LK, Chen PC, Lee KK, Kaur J. Menstruation among adolescent girls in Malaysia: a cross-sectional school survey. Singapore Med J. 2006;47(10):869–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cakir M, Mungan I, Karakas T, Girisken I, Okten A. Menstrual pattern and common menstrual disorders among university students in Turkey. Pediatr Int. 2007;49(6):938–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burnett MA, Antao V, Black A, Feldman K, Grenville A, Lea R, et al. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27(8):765–70. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30728-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nahid K, Fariborz M, Ataolah G, Solokian S. The effect of an Iranian herbal drug on primary dysmenorrhea: a clinical controlled trial. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54(5):401–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawood M, Khan-Dawood F. Clinical efficacy and differential inhibition of menstrual fluid prostaglandin F 2α in a randomized, double-blind, crossover treatment with placebo, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen in primary dysmenorrhea. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;196(1):35. e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia W, Wang X, Xu D, Zhao A, Zhang Y. Common traditional Chinese medicinal herbs for dysmenorrhea. Phytother Res. 2006;20(10):819–24. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modaress Nejad V, Asadipour M. Comparison of the effectiveness of fennel and mefenamic acid on pain intensity in dysmenorrhoea. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12(3-4):423–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asmarian S, Gholami L, Rahmanian Koshkaki E, Kargar Jahromi H, Bathaee S, Farzam M. Investigating Antioxidant Effect of Cinnamon Extract on Elimination of Toxicity of Gelofen Drug in Kidney Tissue of Female Rats. World Journal of Zoology. 2013;8(4):401–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Wang X, Wang W, Chen C, Ronnennberg AG, Guang W, et al. Stress and dysmenorrhoea: a population based prospective study. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(12):1021–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.012302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]