Abstract

Objective To evaluate the role of intervening hospital admissions on trajectories of disability in the last year of life.

Design Prospective cohort study.

Setting Greater New Haven, Connecticut, United States, from March 1998 to June 2013.

Participants 552 decedents from a cohort of 754 community living people, aged 70 years or older, who were initially non-disabled in four essential activities of daily living: bathing, dressing, walking, and transferring.

Main outcome measure Occurrence of admissions to hospital and severity of disability (range 0-4), ascertained during monthly interviews for more than 15 years.

Results In the last year of life, six distinct trajectories of disability were identified, from least disabled to most disabled: 95 participants (17.2%) had no disability, 61 (11.1%) had catastrophic disability, 53 (9.6%) had accelerated disability, 61 (11.1%) had progressively mild disability, 127 (23.0%) had progressively severe disability, and 155 (28.1%) had persistently severe disability. 392 (71.0%) participants had at least one hospital admission and 248 (44.9%) had multiple hospital admissions. For each trajectory the course of disability closely tracked the monthly prevalence of hospital admission. In a set of multivariable models that included several potential confounders, hospital admission in a given month had a strong independent effect on the severity of disability, in both relative and absolute terms. The largest absolute effect was observed for catastrophic disability, with a mean increase in disability score of 1.9 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 2.4) in the setting of a hospital admission, corresponding to a rate ratio (or relative effect) of 2.0 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 2.7).

Conclusions In the last year of life, acute hospital admissions play an important role in the disabling process. Knowledge about the course of disability before these intervening events may facilitate clinical decision making at the end of life. For older patients admitted to hospital with progressive or persistent levels of severe disability, representing more than half of the decedents, clinicians might consider a palliative care approach to facilitate discussions about advance care planning and to better deal with personal care needs.

Introduction

Understanding the disabling process at the end of life is essential for informed decision making among older people and their families and physicians. In an earlier study1 we identified five clinically distinct trajectories of disability in the last year of life and showed that the distribution of these trajectories was varied for several different conditions leading to death, including organ failure, cancer, and frailty. These results suggested that the course of disability in the last year of life does not follow a predictable pattern for most older people based on the condition leading to death, raising questions about the mechanisms underlying the disabling process at the end of life.

One possibility is that disability trajectories at the end of life are driven, at least in part, by acute hospital admissions, through the deleterious effects of the presenting illness or injury and the known hazards of hospital stay itself.2 In support of this possibility we have shown that hospital admission in older people is associated with worsening functional ability for nearly all transitions between states of no disability, mild disability, and severe disability from one month to the next over the course of more than 10 years.3 Whether hospital admissions have a comparable effect on trajectories of disability at the end of life is unknown. Addressing this could help to inform decisions about the prevention and management of disability, potential treatments, and level of care at the end of life.

We evaluated the relation between intervening hospital admissions and trajectories of disability in the last year of life. We used data from a unique longitudinal study that includes monthly assessments of hospital admissions and disability in essential activities of daily living for more than 15 years in a large cohort of community living older people.

Methods

Study population

Participants were drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study, described in detail elsewhere,4 5 of 754 community living people, aged 70 or older, who were initially non-disabled in four essential activities of daily living: bathing, dressing, walking, and transferring. Potential participants were members of a large health plan in Greater New Haven, Connecticut, United States and were excluded if they had major cognitive impairment and no available proxy, had a life expectancy of less than 12 months, had plans to move out of the area, or were unable to speak English. People with slow gait speed were oversampled. Only 126 of the 2735 (4.6%) people contacted refused screening, and 75.2% of the 1002 eligible people agreed to participate and were enrolled from March 1998 to October 1999. Those who refused to participate did not differ significantly from those who were enrolled in terms of age or sex.

Of the 580 participants who had died by 30 June 2013, 28 (4.8%) had dropped out of the study after a median follow-up of 26 months, leaving 552 decedents in the analytic sample.

Data collection

Comprehensive home based assessments were completed at baseline and subsequently at 18 month intervals for 162 months (except for at 126 months), whereas telephone interviews were completed monthly through June 2013. For participants who had considerable cognitive impairment or were otherwise unavailable, we interviewed a proxy using a rigorous protocol, with demonstrated reliability and validity.6 Deaths were ascertained from local obituaries or an informant, or both, during a subsequent interview. A single nosologist who had access to no other participant data coded cause of death using information from the death certificate.1 During the comprehensive assessments, we collected data on demographic characteristics, cognitive status as assessed by the mini-mental state examination,7 frailty according to the Fried phenotype,8 a modified version of the short physical performance battery,9 10 and nine self reported, physician diagnosed chronic conditions.3 Data on these factors were 100% complete at baseline and greater than 95% complete during the subsequent comprehensive assessments.

Assessment of hospital admission

During the monthly interviews we asked participants whether they had stayed at least overnight in a hospital since the last interview—that is, during the past month. The accuracy of these reports, based on an independent review of hospital records among a subgroup of 94 participants, was high (κ=0.94).11 Participants who were admitted to hospital were asked to provide the primary reason for their admission. We subsequently grouped these reasons into distinct diagnostic categories using a revised version of the protocol described elsewhere.12 13

Assessment of disability

Complete details regarding the assessment of disability, including formal tests of reliability and accuracy, are provided elsewhere.6 14 15 During the monthly interviews, we assessed participants for disability using standard questions that were identical to those used during the screening telephone interview. For each of the four essential activities, we asked, “At the present time, do you need help from another person to (complete the task)?” Disability was operationalized as the need for personal assistance, and we denoted the severity of disability by the number of disabled activities (from 0 to 4) in a specific month. We considered disability in one or two activities of daily living as mild and disability in three or four activities of daily living as severe.14 16

The completion rate for the monthly interviews was greater than 99%, with little difference between the decedents and non-decedents. More than 90% of the monthly interviews were completed within the desired two week window (that is, one week before and one week after the target date). The median number of attempts per completed interview was 1 (interquartile range 1-2) and the mean was 1.8 (SD 1.5). To deal with the small amount of missing data on disability, we used multiple imputation with 100 random draws per missing observation.17

Classification of conditions leading to death

We used the information from death certificates and the comprehensive assessments to classify the condition leading to death, according to the protocol provided in appendix table 1 on bmj.com.1

Participant involvement

Members of the target population participated in pilot testing but were not otherwise involved in the design of the study. We selected disability in essential activities of daily living as the primary outcome because maintaining independent function is a primary goal for older people.18 Every 18 months, participants were sent a newsletter highlighting the most important findings from the study.

Statistical analysis

To identify clinically distinct trajectories of disability, we used trajectory modeling,19 which is a form of latent class analysis. This method allowed us to simultaneously estimate each participant’s probabilities for membership in multiple trajectories, with assignment to a specific trajectory based on the highest probability of membership. We used PROC TRAJ in SAS,19 20 which fits a semiparametric (discrete) mixture model to longitudinal data using the maximum likelihood method. We modeled the number of disabled activities per month in the last year of life as a zero inflated Poisson distribution.21 The bayesian information criterion was used to determine the number of disability trajectories and whether each trajectory was best fit by intercept only or by linear, quadratic, or cubic terms.19 22 We evaluated the adequacy of the final models using the average posterior probabilities of class membership; a value of 0.9 or more within each trajectory is considered an excellent fit, whereas less than 0.7 is considered a poor fit.23 The proportions of decedents assigned to each trajectory, mean probability of membership, and proportions with poor fit are based on the original data, and we estimated 95% confidence intervals using 1000 bootstrapped samples.24

We assessed relevant decedent characteristics according to the disability trajectories. Frequency distributions were calculated for the conditions leading to death and the number of hospital admissions in the last year of life.

To evaluate the relation between hospital admissions and disability trajectories, we first plotted the prevalence of hospital admission and severity of disability during each month in the last year of life on a single graph for each of the disability trajectories. We then formally modeled the association between hospital admissions and disability scores through the use of two trajectory specific Poisson models that invoked generalized estimating equations with a first order autoregressive covariance structure to account for correlation among repeated observations within the same participant. The first model used a log link function to generate a relative effect (or rate ratio),25 whereas the second model used an identify link to generate an absolute effect.25 The rate ratio represents the relative increase in the predicted disability score based on the occurrence of a hospital admission in a given month, while the absolute effect represents the mean increase in the predicted disability score based on the occurrence of a hospital admission in a given month. The multivariable models included hospital admission in month t and time (that is, month t). We included time to account for unmeasured factors that could worsen disability at the end of life. Measured covariates included age, sex, race, education, number of chronic conditions, and scores on the mini-mental state examination and short physical performance battery.

All analyses were performed using SAS V9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and we considered P<0.05 (two tailed) to denote statistical significance.

Results

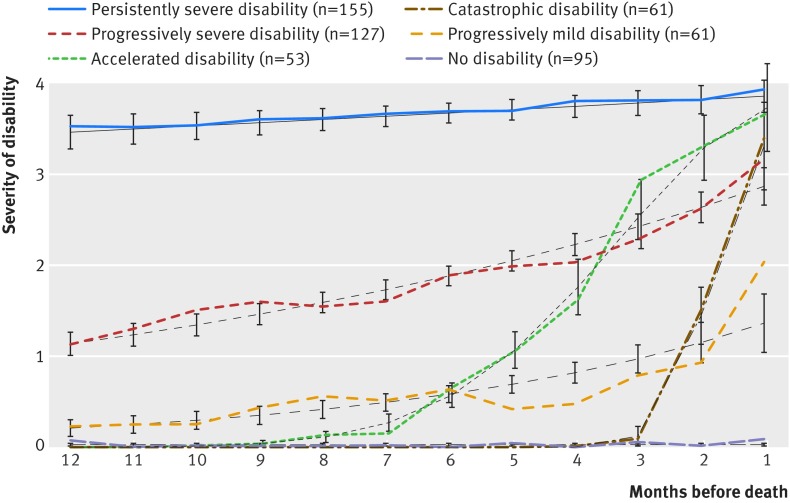

Six distinct trajectories in the last year of life were identified: no disability, catastrophic disability, accelerated disability, progressively mild disability, progressively severe disability, and persistently severe disability (fig 1 ). On average, a year before death, four of the groups—those with no, catastrophic, accelerated, and progressively mild disability (which combined accounted for nearly half of all decedents)—were largely free of disability, whereas the other two disability groups—progressively severe and persistently severe—had mild and severe disability, respectively. The trajectories of the accelerated and catastrophic groups diverged from that of the non-disabled group at about seven and two months before death, respectively. Over the course of the year, the severity of disability in the two progressive groups increased gradually, whereas that in the persistently severe group was near the maximum and changed little.

Fig 1 Trajectories of disability in last year of life among 552 decedents. Values for severity of disability represent the mean number of disabled activities of daily living (from 0 to 4). Black lines depict predicted trajectories, and companion lines depict observed trajectories. Ι bars represent 95% confidence intervals for predicted disability scores. Only 45 (8.2%) of the decedents had a probability of their assigned trajectory <0.70, with values ranging from 0.48 to 0.68; and in all cases, an adjacent trajectory had the next highest probability of membership, with values ranging from 0.16 to 0.42. Nearly 78% (n=35) of these trajectories were characterized by episodes of recovery from a more severe form of disability, while 20% (n=9) were characterized by disability in a single activity in the month before death without any preceding disability

For four of the disability trajectories—no, catastrophic, accelerated, and persistently severe disabilities, the predicted values for severity of disability did not differ from the observed values. For the progressively mild trajectory, the predicted value underestimated the observed value at months 8 and 1 and overestimated the observed value at months 5, 4, and 3. For the progressively severe trajectory, the predicted value underestimated the observed value at month 10 and overestimated the observed value at month 4. None the less, the mean probability of membership for each trajectory was 0.9 or higher except for progressively mild disability, with a value of 0.89.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the decedents according to the disability trajectory in the last year of life. The mean age ranged from 83.9 years in the no disability group to 88.9 years in the persistently severe disability group. Women were overrepresented in the persistently severe disability group. There were only modest differences in race or ethnicity and number of chronic conditions across the six groups. The catastrophic disability group had the highest educational level, whereas the persistently severe disability group had the lowest. Low scores on the mini-mental state examination and short physical performance battery were observed most commonly for the progressively severe and persistently severe disability groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of decedents in last year of life according to disability trajectory. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Disability trajectory* | Decedents | Mean (SD) age (years) | Female sex | Non-Hispanic white† | Mean (SD) education (years) | Mean (SD) chronic conditions‡ | MMSE score <24 | SPPB score <8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No disability | 95 (17.2) | 83.9 (5.7) | 56 (59.0) | 89 (93.7) | 12.1 (2.8) | 2.3 (1.3) | 13 (13.7) | 71 (74.7) |

| Catastrophic disability | 61 (11.1) | 84.1 (6.3) | 27 (44.3) | 55 (90.2) | 12.3 (2.6) | 2.4 (1.4) | 6 (9.8) | 45 (73.8) |

| Accelerated disability | 53 (9.6) | 84.0 (6.1) | 26 (49.1) | 50 (94.3) | 11.9 (2.9) | 2.5 (1.2) | 8 (15.1) | 40 (75.5) |

| Progressively mild disability | 61 (11.1) | 85.5 (5.6) | 32 (52.5) | 56 (91.8) | 12.1 (2.9) | 2.6 (1.1) | 14 (23.0) | 49 (80.3) |

| Progressively severe disability | 127 (23.0) | 87.3 (5.3) | 81 (63.8) | 115 (90.6) | 12.0 (3.2) | 2.6 (1.4) | 44 (34.7) | 119 (93.7) |

| Persistently severe disability | 155 (28.1) | 88.9 (5.4) | 118 (76.1) | 139 (89.7) | 11.5 (2.9) | 2.5 (1.5) | 114 (73.6) | 151 (97.4) |

| Overall | 552 (100) | 86.3 (6.0) | 340 (61.6) | 504 (91.3) | 11.9 (2.9) | 2.5 (1.3) | 199 (36.1) | 475 (86.1) |

MMSE=mini-mental state examination; SPPB=short physical performance battery.

Age was determined at beginning of the disability trajectory, and the number of chronic conditions, MMSE, and SPPB were determined during the comprehensive assessment at or immediately before the beginning of the disability trajectory.

*95% confidence intervals for frequency distribution, based on 1000 bootstrap samples, were 12.7 to 20.5 for no disability group, 8.7 to 15.4 for catastrophic disability group, 4.9 to 17.8 for accelerated disability group, 4.0 to 15.4 for progressively mild disability group, 18.7 to 27.5 for progressively severe disability group, and 23.4 to 33.3 for persistently severe disability group.

†Race or ethnic group was self reported.

‡Included hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, hip fracture, chronic lung disease, and cancer.

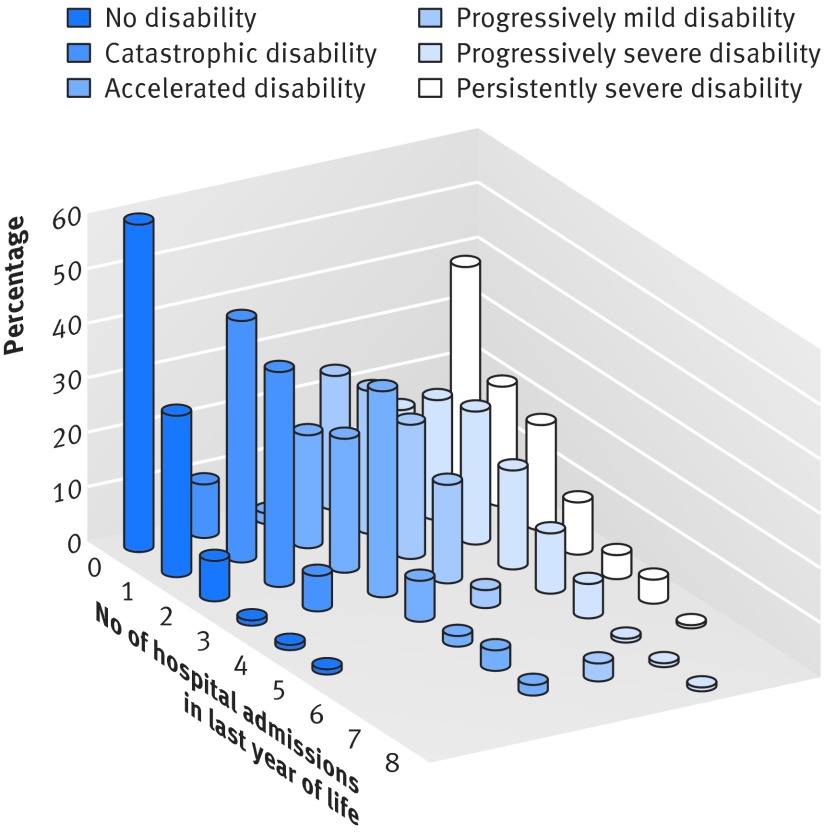

The most common condition leading to death was frailty (27.9%, n=154), followed by organ failure (21.4%, n=118), cancer (18.1%, n=100), advanced dementia (17.4%, n=96), other (12.7%, n=70), and sudden (2.5%, n=14). Overall, 392 (71.0%) participants had at least one hospital admission in the last year of life and 248 (44.9%) had multiple hospital admissions. The frequency distribution of these hospital admissions differed considerably across the disability trajectories (fig 2 ), with the largest number observed for accelerated disability and the smallest number observed for no disability. Table 2 shows the primary reasons for hospital admission. With the exception of the progressively severe disability trajectory, which included a disproportionate number of hospital admissions for infection, the most common reason for hospital admission was other medical conditions. The no disability trajectory included the largest proportion of cardiac hospital admissions, whereas the catastrophic disability trajectory included the largest proportion of cancer hospital admissions. Differences across the disability trajectories were otherwise modest.

Fig 2 Frequency distribution for number of hospital admissions in last year of life according to disability trajectory

Table 2.

Reasons for admission to hospital in last year of life according to disability trajectory. Values are numbers (percentages)* with disability trajectory

| Reasons for hospital admission | Disability trajectory | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No disability (n=53) | Catastrophic disability (n=87) | Accelerated disability (n=137) | Progressively mild disability (n=102) | Progressively severe disability (n=276) | Persistently severe disability (n=208) | |

| Cardiac | 17 (32.1) | 13 (21.6) | 26 (16.3) | 22 (14.9) | 45 (11.1) | 23 (19.0) |

| Infection | 8 (15.1) | 18 (17.6) | 26 (22.8) | 18 (20.7) | 63 (33.2) | 69 (19.0) |

| Fall related injury | 1 (1.9) | 4 (2.9) | 6 (2.9) | 3 (4.6) | 8 (4.8) | 10 (4.4) |

| Stroke | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.9) | 7 (6.9) | 4 (4.6) | 19 (5.3) | 11 (5.1) |

| Arthritis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (1.1) | 6 (2.9) |

| Cancer | 3 (5.7) | 13 (14.9) | 14 (10.2) | 9 (8.8) | 11 (4.0) | 5 (2.4) |

| Gastrointestinal tract bleeding | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (2.0) | 7 (2.5) | 4 (1.9) |

| Other: | ||||||

| Medical | 18 (34.0) | 24 (27.6) | 39 (28.5) | 33 (32.4) | 86 (31.2) | 71 (34.1) |

| Surgical | 4 (7.5) | 7 (8.0) | 11 (8.0) | 9 (8.8) | 19 (6.9) | 3 (1.4) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (5.4) | 6 (2.9) |

*Represents number (percentage) of hospital admissions for a specific reason among all hospital admissions in last year of life for each disability trajectory; column percentages may not add up to 100 because of rounding.

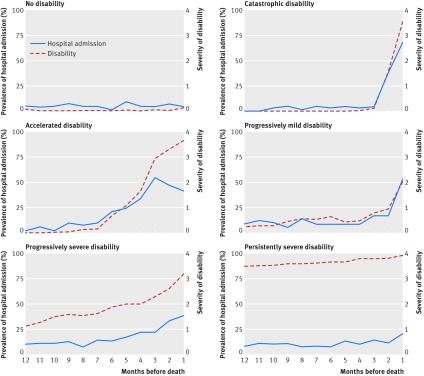

Figure 3 plots the prevalence of hospital admission and severity of disability during each month in the last year of life according to disability trajectory. Without exception, the course of disability closely tracked the monthly prevalence of hospital admission. This tight linkage between hospital admission and disability severity was particularly evident for the progressively mild and catastrophic trajectories, for which the two plots were nearly superimposed. For the no disability trajectory, the prevalence of hospital admission was very low throughout the year. Although the values were a bit higher, the monthly prevalence of hospital admission was similarly flat for the persistently severe trajectory, mirroring the course of disability throughout the year. For the accelerated trajectory, the two plots tracked one another closely until two months before death when the severity of disability continued to increase despite a modest reduction in the prevalence of hospital admission.

Fig 3 Prevalence of hospital admission and severity of disability during each month in last year of life according to disability trajectory. Values for severity of disability represent the mean number of disabled activities of daily living (from 0 to 4)

Table 3 provides the multivariable associations between hospital admissions and severity of disability according to disability trajectory. For each of the trajectories, hospital admission in a given month had a strong independent effect on the severity of disability, in both relative and absolute terms. The largest absolute effect was observed for catastrophic disability, with a mean increase in disability score of 1.9 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 2.4) in the setting of a hospital admission, corresponding to a rate ratio (or relative effect) of 2.0 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 2.7). For no disability, the relative effect of hospital admission was large, reflecting the very low disability scores among participants in this group, while the absolute effect of hospital admission was small, with a mean increase in disability score of 0.1 (95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.3). The relative and absolute effects of hospital admission were also small for participants in the persistently severe trajectory, who had high levels of disability throughout the last year of life.

Table 3.

Multivariable associations between admissions to hospital and severity of disability according to disability trajectory in last year of life

| Disability trajectory | Relative effect | Absolute effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate ratio (95% CI) | P value | Mean increase (95% CI) | P value | ||

| No disability | 7.1 (2.5 to 19) | <0.001 | 0.1 (0.01 to 0.3) | 0.037 | |

| Catastrophic disability | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.7) | <0.001 | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.4) | <0.001 | |

| Accelerated disability | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.4) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Progressively mild disability | 3.1 (2.3 to 4.1) | <0.001 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Progressively severe disability | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | <0.001 | |

| Persistently severe disability | 1.1 (1.1 to 1.1) | <0.001 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | <0.001 | |

*Multivariable Poisson models were run using generalized estimating equations, with a log link function to generate a relative effect and an identify link to generate an absolute effect, and a first order autoregressive covariance structure to account for correlation among repeated observations within the same participant. Covariates included age >85 years, sex, race (non-Hispanic white versus other), education in years, number of chronic conditions, mini-mental state examination score <24, short physical performance battery score <8, and time (that is, month in last year of life). The severity of disability was operationalized as the mean number of disabled activities of daily living (from 0 to 4).

†Relative increase in predicted disability score based on occurrence of a hospital admission in a given month.

‡Mean increase in predicted disability score based on occurrence of a hospital admission in a given month.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of community living older people, we found strong associations between the occurrence of acute hospital admissions and the course of disability for six distinct functional trajectories in the last year of life. These associations were shown graphically, with the course of disability closely tracking the monthly prevalence of hospital admission for each of the trajectories and were confirmed through a set of multivariable models that accounted for several potential confounders. These results provide new information about the role of intervening hospital admissions on the disabling process in the last year of life. Knowledge about the course of disability before these intervening events may facilitate clinical decision making at the end of life.

In an earlier study1 we showed that the course of disability in the last year of life does not follow a predictable pattern for most older people based on the condition leading to death, raising questions about the cause of disability at the end of life. The results of the current study suggest that the disabling process in the last year of life is strongly influenced by the occurrence of acute hospital admissions. This phenomenon was most evident for catastrophic disability, which was characterized by an abrupt onset of severe disability in the last few months of life corresponding to a large increase in the likelihood of hospital admission, but was also readily apparent for accelerated disability, which was characterized by a substantial increase in disability severity over the last six months of life, corresponding to a comparable increase in the likelihood of hospital admission. The low prevalence of hospital admission in the last year of life for the no disability group indicates that the severity of disability does not increase in the absence of a hospital admission, thereby providing additional evidence to support the role of intervening hospital admissions on the disabling process.

The adverse functional consequences of acute hospital admissions have been shown previously for a series of clinically meaningful transitions in activities of daily living disability from one month to the next3 and for the onset of long term disability in community mobility.15 The deleterious effects of these intervening events are likely attributable to both the underlying illness or injury leading to hospital admission, and the well known hazards of hospital admission itself.2 26 In the current study the most common reasons for hospital admission were cardiac, infection, cancer, and other medical conditions.

Clinical implications

Our results may help to inform decisions about the prevention and management of disability, potential treatments, and level of care at the end of life. Because functional status is one of the strongest predictors of mortality among older people,27 28 29 aggressive efforts are warranted to minimize the adverse functional consequences of acute hospital admissions,30 31 32 33 34 and, post event, to enhance restorative interventions in the subacute, home care, and outpatient settings,35 36 especially among older people with previously low levels of disability. Based on our results, about half of older people have little to no disability a year before their death, whereas the other half have progressive or persistent levels of severe disability. For this latter group, care needs are substantial and mortality is high.37 38 Access to palliative care could deal with these needs, while also offering symptom management, family support, and advance care planning, including discussions about foregoing subsequent hospital admissions.39 Similar services may also be valuable for older people with an accelerated course or catastrophic onset of severe disability, independent of prognosis and treatment decisions. Given the adverse functional consequences of acute hospital admissions, efforts are also warranted to prevent their initial occurrence, when possible,40 41 and to reduce the likelihood of subsequent admissions after an index hospital admission,42 43 44 45 46 a scenario that was observed commonly among participants with each of the trajectories other than no disability.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The availability of prospective longitudinal data on functional status at monthly intervals allowed us to identify six distinct trajectories of disability, ranging from no disability to persistently severe disability. Five of these trajectories were comparable to those identified in our earlier study, which included 169 fewer decedents.1 Identification of progressively mild disability as an additional trajectory, one that had the poorest fit of the six trajectories, is likely due to the inclusion of decedents who had accrued since the earlier study. The addition of these decedents, however, did not alter the distribution of conditions leading to death.1

The validity of our results is strengthened by the nearly complete ascertainment of hospital admission and disability, the high reliability and accuracy of these assessments, the low rate of attrition, and adjustment for several relevant covariates. None the less, our results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Firstly, because this was an observational study, the reported associations cannot be construed as causal relations. The frequency of our assessments increases the likelihood that the intervening events preceded (or were concurrent with) the demonstrated changes in disability, thereby strengthening temporal precedence and supporting a causal association. Although reverse causality is a possibility, it is unlikely that increasing disability led to some of the most common reasons for hospital admission, including cardiac, infection, stroke, and cancer. Secondly, information was not available on the severity of the illnesses or injuries leading to hospital admission, on hospital acquired complications, or on length of stay or post-hospital course. Hence it is not possible to disentangle the adverse consequences of the underlying condition leading to hospital admission from those of the hospital admission itself. Thirdly, information on receipt of palliative care or hospice care was not available in the current study. It is unlikely that hospice care had any meaningful effect on our results since only a minority of Medicare decedents, including those with a cancer diagnosis, access three or more days of hospice services, and the median length of stay in hospice is short—that is, less than three weeks.47 Finally, because our study participants were members of a single health plan in a small urban area in the US and were oversampled for slow gait speed, our results may not be generalizable to older people in other settings. However, the demographic characteristics of our cohort did reflect those of older people in New Haven County, Connecticut, which are similar to the characteristics of the US population as a whole, with the exception of race or ethnic group.48 The generalizability of our results is enhanced by our high participation rate, which was greater than 75%.

Conclusion

The results of this observational study suggest that acute illnesses and injuries leading to hospital admission play an important role in the disabling process at the end of life. Knowledge about the course of disability before these intervening events may help older people, together with their families and physicians, to make informed decisions about potential treatments and level of care that are consistent with their preferences, goals, and prognosis. For older patients admitted to hospital with progressive or persistent levels of severe disability, representing more than half of the decedents, clinicians might consider a palliative care approach to facilitate discussions about advance care planning and to better deal with personal care needs.

What is already known on this topic

Understanding the disabling process at the end of life is essential for informed decision making among older people and their families and physicians

The course of disability at the end of life does not follow a predictable pattern for most older people based on the condition leading to death

What this study adds

In the last year of life the occurrence of acute illnesses and injuries leading to hospital admission were strongly associated with the course of disability for six distinct functional trajectories

Knowledge about the course of disability before these intervening events may facilitate clinical decision making at the end of life

We thank Denise Shepard, Andrea Benjamin, Barbara Foster, and Amy Shelton for assistance with data collection; Wanda Carr and Geraldine Hawthorne for assistance with data entry and management; Linda Leo-Summers for assistance with the figures; Peter Charpentier for design and development of the study database and participant tracking system; Joanne McGloin for leadership and advice as the project director; and our participants for sharing information about their health and function over the past 17 years.

Contributors: LH conducted the statistical analyses under the supervision of HGA. All authors participated in designing the analyses, interpreting the results, and writing the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and are guarantors for the study.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R37AG17560, R01AG022993). The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342). TMG is the recipient of an academic leadership award (K07AG043587) from the National Institute on Aging. The funders had no role in the conduct of the research.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee at Yale School of Medicine; each participant provided informed consent.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead author (TMG) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h2361

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Protocol for classifying the condition leading to death

References

- 1.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, et al. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1173-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA 2011;306:1782-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, et al. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA 2010;304:1919-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, et al. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:313-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill TM. Disentangling the disabling process: insights from the Precipitating Events Project. Gerontologist 2014;54:533-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill TM, Hardy SE, Williams CS. Underestimation of disability among community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, et al. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:418-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, et al. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 1995;332:556-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Barry LC, et al. Risk factors for disability subtypes in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1850-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill TM, Allore H, Holford TR, et al. The development of insidious disability in activities of daily living among community-living older persons. Am J Med 2004;117:484-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, et al. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA 2004;292:2115-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Pahor M, et al. Hospital diagnoses, Medicare charges, and nursing home admissions in the year when older persons become severely disabled. JAMA 1997;277:728-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. JAMA 2004;291:1596-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE, et al. Risk factors and precipitants of long-term disability in community mobility: a cohort study of older persons. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:131-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy SE, Dubin JA, Holford TR, et al. Transitions between states of disability and independence among older persons. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:575-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill TM, Guo Z, Allore HG. Subtypes of disability in older persons over the course of nearly 8 years. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:436-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill TM. Assessment of function and disability in longitudinal studies. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(Suppl 2):S308-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixed models for estimating developmental trajectories. Socio Meth Res 2001;29:374-93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Socio Meth Res 2007;35:542-71. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee AH, Wang K, Scott JA, et al. Multi-level zero-inflated poisson regression modelling of correlated count data with excess zeros. Stat Methods Med Res 2006;15:47-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, ed. The Sage handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Sage; 2004.

- 23.Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press; 2005.

- 24.Effron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; 1993.

- 25.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger S. Analysis of longitudinal data. Clarendon Press; 1994.

- 26.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:219-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrold J, Rickerson E, Carroll JT, et al. Is the palliative performance scale a useful predictor of mortality in a heterogeneous hospice population? J Palliat Med 2005;8:503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, et al. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA 1998;279:1187-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carey EC, Walter LC, Lindquist K, et al. Development and validation of a functional morbidity index to predict mortality in community-dwelling elders. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1027-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rich MW. Heart failure in the 21st century: a cardiogeriatric syndrome. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56A:M88-96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1338-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, et al. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med 2002;346:905-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1157-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA 2014;311:2169-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tinetti ME, Baker D, Gallo WT, et al. Evaluation of restorative care vs usual care for older adults receiving an acute episode of home care. JAMA 2002;287:2098-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoenig H, Nusbaum N, Brummel-Smith K. Geriatric rehabilitation: state of the art. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:1371-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Simonsick E, et al. Progressive versus catastrophic disability: a longitudinal view of the disablement process. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1996;51A:M123-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Alpert JS, Powers PJ. Who will care for the frail elderly? Am J Med 2007;120:469-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed]

- 40.Tinetti ME. Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2003;348:42-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Straus SE, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA. New evidence for stroke prevention: clinical applications. JAMA 2002;288:1396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999;281:613-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flood KL, Maclennan PA, McGrew D, et al. Effects of an acute care for elders unit on costs and 30-day readmissions. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:981-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ottenbacher KJ, Karmarkar A, Graham JE, et al. Thirty-day hospital readmission following discharge from postacute rehabilitation in fee-for-service medicare patients. JAMA 2014;311:604-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization facts and figures. Hospice care in America, 2013. www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2013_Facts_Figures.pdf.

- 48.US Census Bureau. American factfinder. 2013. http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Protocol for classifying the condition leading to death