Abstract

This case series describes the development of a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for older adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa (AN). Emotion acceptance behavior therapy (EABT) is based on a model that emphasizes the role of anorexic symptoms in facilitating avoidance of emotions. EABT combines standard behavioral interventions that are central to the clinical management of AN with psychotherapeutic techniques designed to increase emotion awareness, decrease emotion avoidance, and encourage resumption of valued activities and relationships outside the eating disorder. Five AN patients ages 17-43 years were offered a 24-session manualized version of EABT. Four patients completed at least 90% of the therapy sessions, and three showed modest weight gains without return to intensive treatment. Improvements in depressive and anxiety symptoms, emotion avoidance, and quality of life also were observed. These results offer preliminary support for the potential utility of EABT in the treatment of older adolescents and adults with AN.

The absence of evidence-based treatments for older adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa (AN) is one of the most serious issues in the eating disorders field. Although family therapy has shown promise in the treatment of younger adolescents who have been ill for a relatively short time (1), this approach generally is not recommended for individuals age 17 years and older who comprise the majority of AN patients (2). Preliminary reports have suggested the utility of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in preventing relapse among adults with AN who have achieved weight restoration (3, 4). However, the results from one study indicate that CBT may not be the optimal approach for treating underweight individuals with AN (5). In the current U.S. care environment, few AN patients are fully weight-recovered at discharge from inpatient or day hospital settings (6). Moreover, many individuals with AN do not have access to structured treatment programs that provide nutrition rehabilitation or address eating disorder psychopathology. Thus, there is a critical need for the development of effective outpatient interventions for underweight individuals with AN.

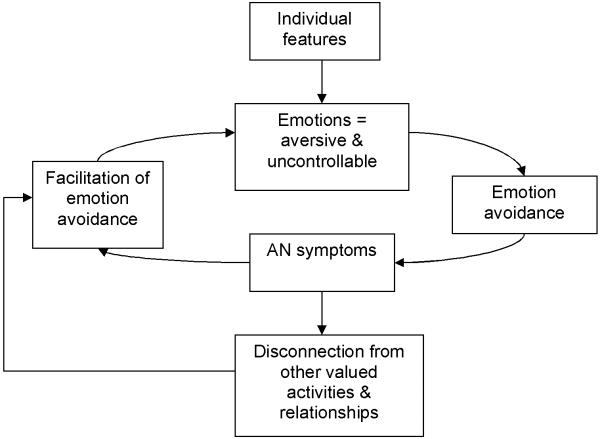

Emotion acceptance behavior therapy (EABT) is an outpatient psychotherapeutic intervention designed specifically for older adolescents and adults with AN. The principles of EABT derive from empirical work on the psychopathology and treatment of AN, clinical experience, and the general psychotherapy research literature. Consistent with the early writings of Bruch (7) and Slade (8), as well as more recent formulations of AN and other eating disorders [see, e.g., (9, 10)], EABT is based on a conceptual model that emphasizes the role of anorexic symptoms in facilitating avoidance of emotions (see Figure 1). Drawing on an extensive body of clinical research [see, e.g., (11-13)], the EABT model postulates that people with AN often are characterized by individual features, such as inhibited or harm avoidant personality traits and problems with anxiety and mood disturbance, that shape their experience of emotion as aversive and uncontrollable. This negative experience of emotion results in “emotion avoidance,” that is, the desire to avoid experiencing or expressing physical sensations, thoughts, urges, and behaviors related to emotional states. Anorexic symptoms (e.g., extreme dietary restraint, purging, excessive exercise, ruminative thoughts about eating, shape, or weight) are hypothesized to serve the function of facilitating emotion avoidance by a) preventing patients from experiencing emotions and b) reducing the intensity and duration of emotional reactions. Several recent theorists have postulated that abnormalities in fear conditioning and discomfort experiencing novelty or change may signal an “emotional endophenotype” (p. 216) (13) of AN characterized, in part, by phobic avoidance (11-13). Moreover, some scholars have speculated that dietary restraint may serve an anxiolytic function for some individuals, which could play a role in the expression and maintenance of anorexic psychopathology (11, 12). Thus, the theoretical framework that underlies EABT is supported both by early clinical observations of AN (7, 8), as well as more recent in work in the field (10-12).

Figure 1.

EABT Model of Emotion Avoidance in Anorexia Nervosa

The EABT model assumes that emotion avoidance poses two main problems for individuals with AN. First, although AN symptoms may be effective at reducing emotions in the short term, over the long term, efforts to avoid emotion may have the paradoxical result of increasing the frequency and intensity of aversive emotional reactions. A vast body of empirical research has documented that attempts to avoid internal stimuli (e.g., emotions, thoughts, physical sensations) are largely ineffective and often result in more (not fewer) unwanted experiences [for review, see (14, 15)]. Thus, in their efforts to avoid emotion, AN patients may find themselves trapped in a cycle of emotional vulnerability, avoidance, and disordered eating. Second, because patients spend so much time focused on AN symptoms, valued goals in other areas of their lives often are neglected. Accordingly, the primary treatment targets in EABT are: 1) AN symptoms, 2) emotion avoidance, and 3) disconnection from other valued activities and relationships.

EABT TREATMENT

The EABT approach to treatment combines standard behavioral interventions that are central to the clinical management of AN (e.g., weight monitoring, prescription of regular, nutritionally-balanced eating) with psychotherapeutic techniques designed to increase emotion awareness, decrease emotion avoidance, and encourage resumption of valued activities and relationships outside the eating disorder. EABT is heavily influenced by what has been termed the “third generation” of behavior therapies [(16), p. 2], examples of which include Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). Third generation behavior therapies are similar to traditional behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches in that they share a commitment to the use of empirically-supported behavior change strategies (e.g., exposure, behavioral analysis); however, these newer methods are distinguished from earlier approaches by an increased emphasis on the context and function of psychological phenomena, as opposed to altering symptom form. Thus, EABT focuses on helping patients to identify the functions served by AN symptoms, including the connection between AN symptoms and emotion avoidance, and to adopt alternative strategies (including cultivating a willingness to experience/tolerate uncomfortable emotions and other avoided experiences) in the service of reconnecting with other valued activities and relationships. However, cognitive strategies focused on altering the frequency or form of AN symptoms (e.g., identifying, challenging, and restructuring dysfunctional thoughts and attitudes about eating, weight, and shape) are not employed.

Session Content

EABT is divided into three phases, but content across therapy sessions is overlapping, and the phases are not intended to be distinct. All sessions include a weight and symptom check-in, review of the past week from the patient’s perspective, and validation of the patient’s concerns about gaining weight and reducing eating disorder symptoms. As in other manualized treatments for AN, a major aim of EABT is to assist patients in achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight and sustaining normal eating. However, because individuals with AN often are ambivalent about relinquishing eating disorder symptoms, the initial focus of symptom management is on weight stability (i.e., preventing additional weight loss) rather than weight gain. As detailed below, individual weight gain/symptom reduction goals are developed jointly by the patient and therapist over the course of treatment, and are based on a shared understanding of the eating disorder including its history, functions, and impact on other valued areas of the patient’s life. Once goals for symptom management have been established, the specific emphasis of these efforts is on helping the patient to resume valued activities and relationships that have been neglected consequent to the onset of disordered eating symptoms. Additional therapeutic strategies employed during each phase of EABT are outlined below.

Phase 1

As in other psychotherapies, the initial sessions of EABT focus on orienting the patient to treatment and building a therapeutic relationship. A major aim of Phase 1 is for the patient and therapist to develop a shared understanding of the patient’s illness with a particular emphasis on the relation between eating disorder symptoms and the patient’s experience of emotion. The EABT model is introduced, and the patient and therapist work together to develop a personalized model that reflects the patient’s history, symptom functions, and values. The ultimate goal of this assessment is for the patient and therapist to establish a conceptualization linking the patient’s AN symptoms to emotion avoidance and illustrating how these behaviors have served to disconnect the patient from other valued activities and relationships. Based on this information, the patient and therapist collaborate to set treatment goals for: 1) weight gain/reduction of eating disorder symptoms, 2) acceptance of emotions and other avoided experiences, and 3) participation in other valued activities and relationships.

Phase 2

The focus of Phase 2 is on helping the patient meet EABT treatment goals using psychotherapeutic techniques adapted from third generation behavior therapies. As described above, third generation approaches emphasize “contextual and experiential” [(17), p. 659] change strategies such as mindfulness, acceptance, and contact with the present moment, as opposed to techniques focused on changing the form of problematic internal experiences (e.g., modifying dysfunctional thoughts about eating, weight, and shape). Thus, if a patient reports being unable to eat at a meal because she feels anxious and fears that “if I start eating, I won’t be able to stop and I’ll get fat,” EABT employs mindfulness strategies to help her observe, describe, and tolerate the feelings, thoughts, and physical sensations related to this experience rather than behavioral experiments or cognitive restructuring focused on challenging the validity of the patient’s predictions. Similarly, graded exposure may be used to help the patient increase willingness to enter situations that provoke aversive emotional reactions (e.g., social settings) or to address concerns more directly related to disordered eating (e.g., anxiety-provoking physical sensations such as bloating or feeling too full). Finally, self-monitoring is employed to help patients identify links between AN symptoms and emotional reactions or disconnection from other valued activities and relationships.

Phase 3

As is the case in other manualized interventions, the final phase of EABT focuses on consolidation of gains, continued practice of behavioral strategies, and planning for the end of treatment. The patient’s personalized model of AN is reviewed and updated and plans for continuing acceptance and value-based living are discussed. The patient and therapist also collaborate to develop a personalized plan for relapse prevention based on the course of therapy.

CASE SERIES

The following case series depicts our experience conducting EABT in four of the first five patients who were offered the treatment. One patient dropped out of EABT after two sessions because of travel concerns (she lived > 2 hours from the study site); thus, her case is not described further here. All patients provided written informed consent for research treatment on forms approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Structure of Treatment

EABT was provided in 24, hour-long sessions conducted individually over 22 weeks. Patients met with their therapist twice per week for the first 4 weeks (sessions 1-8), followed by weekly sessions from weeks 5 through 18 (sessions 9-22), and every other week sessions for the last 4 weeks of treatment (sessions 23 and 24). Patients also received medical monitoring (i.e., assessment of weight and vital signs) from a nurse or nurse practitioner at each appointment and met monthly with the study physician. Finally, because of the primacy of adequate nutrition for weight regain, patients received up to two sessions of nutrition counseling with a registered dietitian.

Therapists

Therapists were masters- or doctoral-level clinicians with experience treating eating disorders. Prior to conducting EABT, therapists reviewed the treatment manual and received didactic instruction in the EABT intervention from the authors. Therapy sessions were audio-taped, and therapists met weekly with the authors for supervision.

Outcomes

Several outcome measures were employed to evaluate the acceptability and preliminary efficacy of EABT. During pre- and post-treatment assessments, patients were interviewed using the Eating Disorder Examination [EDE-16.0D; (18)], and completed a battery of self-report questionnaires including the Beck Depression Inventory-2 [BDI-2 (19)], Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI; (20)], Acceptance and Action Questionnaire [AAQ; (21)], and Eating Disorder Quality of Life Questionnaire [EDQOL; (22)]. Primary outcomes included number of EABT sessions attended and weight gain and improvement in body mass index (BMI) pre- to post-treatment. In addition, we were interested in evaluating whether patients could be treated successfully with EABT without requiring referral for more intensive intervention (i.e., inpatient or day hospital treatment). Secondary outcomes included changes in the cognitive correlates of disordered eating, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, emotion avoidance, and quality of life pre- to post-treatment, as measured by the EDE total score, BDI-2, BAI, AAQ, and EDQOL, respectively.

Case Reports

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients at pre- and post-treatment are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Pre-treatment and Post-treatment in Patients Receiving Emotion Acceptance Behavior Therapy

| Patient # 01 | Patient #02 | Patient # 03 | Patient # 04 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post |

| Age (years) | 25.0 | -- | 22.0 | -- | 39.0 | -- | 17.0 | -- |

| Weight (pounds) | 106.0 | 110.4 | 121.6 | 125.8 | 98.0 | 92.6 | 101.0 | 106.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 17.1 | 17.8 | 18.0 | 18.6 | 16.1 | 15.2 | 18.5 | 19.5 |

| Years since onset of AN | 8.0 | -- | < 1.0 | -- | 15.0 | -- | 3.0 | -- |

| Number of hospitalizations for AN | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Number of EABT sessions attended | -- | 24.0 | -- | 24.0 | -- | 22.0 | -- | 24.0 |

| EDE total score* | 0.8 | 0.0 | 3.8 | ** | 3.6 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| BDI-2 total score* | 24.0 | 0.0 | 35.0 | 23.0 | 17.0 | 13.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 |

| BAI total score* | 9.0 | 4.0 | 21.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 |

| AAQ total score* | 45.0 | 34.0 | 47.0 | 40.0 | 31.0 | 33.0 | 36.0 | 29.0 |

| EDQOL total score* | 1.3 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

Higher scores indicate greater impairment

Patient did not complete post-treatment EDE

AN = anorexia nervosa; EDE = Eating Disorder Examination; BDI-2 = Beck Depression Inventory-2; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; AAQ = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; EDQOL = Eating Disorder Quality of Life Questionnaire

Patient # 01

Patient # 01 was a 25 year-old single, white female with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (23) diagnoses of AN, restricting type (AN-R), panic disorder, and gender identity disorder not otherwise specified. She also had a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Her personalized model revealed a long history of anxiety and discomfort with physical sensations, including onset of obsessive thoughts and rituals at age 7 and avoidance of excitement and “positive experiences” (e.g., field trips) due to fears that she might vomit in these situations.

The patient stated that positive feedback from her mother served as the initial motivation for disordered eating behaviors, but described other functions of anorexic symptomatology that were more relevant at the time of EABT. In particular, the patient reported that eating disorder symptoms “take away unpredictability.” They also help her to avoid “high or low moods” and her period, which she finds aversive. Nevertheless, the patient acknowledged that eating disorder symptoms have interfered with aspects of her life, especially her valued goal of attaining a professional (i.e., master’s) degree. Thus, EABT focused on helping the patient to tolerate unpredictable experiences and avoided emotions without using eating disorder symptoms with the ultimate goal of helping her to complete her education.

The patient was receptive to using self-monitoring techniques and mindfulness skills to increase her awareness of and participation in avoided experiences. She also worked with her therapist to increase her calorie intake. However, she was unwilling to relinquish exercise as a method of relieving stress. At the end of treatment, the patient weighed 110.4 pounds, a 4.4-pound increase from baseline, but she still was underweight (see Table 1). Nevertheless, the patient reported that EABT was helpful and gave her skills that she used to successfully complete a difficult semester in school. The patient also demonstrated improvements on several secondary outcome measures over the course of treatment, as presented in Table 1.

Patient # 02

Patient # 02 was a 22 year-old single, white female with DSM-IV diagnoses of AN-R, major depressive disorder, and social phobia. She also had lifetime histories of alcohol dependence and cannabis abuse. During discussion of her personalized model, the patient reported that she had felt depressed her entire life. She also described feeling anxious, “jealous,” and “competitive” in social situations. The patient stated that her eating disorder symptoms developed shortly after she experienced two losses (i.e., the break-up of a romantic relationship and the end of a friendship) as a way to comfort herself and improve her self-confidence. Specifically, the patient reported that dietary restriction helps her to “cope” with feelings of sadness, loneliness, and anxiety in a manner similar to self-injury.

Although the patient expressed ambivalence about gaining weight and normalizing her eating behaviors, she acknowledged that her tendency to use dietary restriction as a strategy for coping with emotions had interfered with other areas of her life. In particular, the patient noted that her depressive symptoms worsened when she was underweight and, consequently, she had been isolating from supportive friends and family members. Thus, EABT focused on helping the patient to: 1) identify and tolerate aversive emotions without using eating disorder symptoms, and 2) improve relationships with members of her support network.

The patient was receptive to using mindfulness skills and behavioral activation techniques (e.g., activity scheduling) as a means of meeting her EABT treatment goals. She especially liked the idea of “watching” her emotions, thoughts, and physical sensations without responding to or believing them. The patient reported that this exercise helped her to separate herself from her feelings (i.e., “I am not my depression”) and to realize that even the most intense emotions will subside with time. The patient also was able to reconnect with valued relationships during treatment, including one with the boyfriend she was dating prior to the onset of her eating disorder. She demonstrated modest improvements in body weight and secondary outcome measures (see Table 1).

Patient # 03

Patient # 03 was a 39 year-old single, white female with DSM-IV diagnoses of AN, binge-eating/purging type (AN-B/P) and lifetime major depressive disorder. In developing her personalized model, the patient noted that she is a “highly emotional” person, with an “anxious and sensitive” temperament. She reported onset of disordered eating symptoms at age 22 that were exacerbated by her mother’s diagnosis of a severe degenerative illness when the patient was 26. Specifically, the patient reported that she became “so obsessed” with food and the “downward trend on the scale” that she “couldn’t pay attention to anything else.”

The patient agreed that eating disorder symptoms function to “numb my emotional sensitivities,” and help her to “distract” from feelings of sadness, anger, and disappointment. She also noted that AN gives her a “sense of control” over her life, and enables her to express anger towards her father and brother. However, although the patient acknowledged that eating disorder symptoms conflict with her religious beliefs and her desire to demonstrate to her mother that she is able to “take care of myself,” she was unwilling to collaborate with her therapist in setting goals for weight gain or reduction of purging behaviors. In particular, the patient reported that she was happy with her current weight and feared that she would be “overwhelmed by emotion” if she relinquished eating disorder symptoms.

The therapist used validation and motivational enhancement techniques (e.g., siding with the eating disorder, helping the patient identify discrepancies between eating disorder symptoms and other values) to encourage small steps towards recovery. She also attempted to use mindfulness techniques and guided imagery (e.g., imagining a trip to the supermarket to purchase food) to help the patient cope with aversive emotions related to increasing her calorie intake and decreasing purging, but the patient reported feeling “too overwhelmed” to complete these exercises. Although the patient attended all scheduled therapy sessions and reported that she liked EABT, her eating disorder symptoms worsened during treatment. She was unreceptive to adjunctive interventions (i.e., appointments with the dietitian) and attempts to increase the intensity of treatment (e.g., by offering twice weekly sessions). Because her weight dropped continuously and she had electrolyte abnormalities consequent to purging (i.e., low sodium and chloride), the patient was withdrawn from EABT after session 22, and referred to an inpatient eating disorders program. Changes in body weight and secondary outcomes over the course of treatment are reported in Table 1.

Patient # 04

Patient # 04 was a 17-year old single, white female with AN-R, and no current or lifetime co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses. When developing her personalized model, the patient reported that she tends to be removed from her feelings, and prefers not to experience emotions fully. In particular, the patient noted that although some emotions (e.g., happiness, anger, jealously) are “OK”, others (e.g., sadness, embarrassment) are “unacceptable” because they reflect “weakness.” She acknowledged that eating disorder behaviors serve as a form of control over emotions; however, she also reported that she tends to feel more sad and irritable when she is underweight.

EABT focused on helping the patient to experience and tolerate emotions in the service of valued goals that are inconsistent with her eating disorder. The patient was receptive to behavioral activation techniques focused on increasing her participation in valued domains (e.g., monitoring and scheduling activities with friends). However, she struggled to identify emotions besides irritability and anger, and most of Phase 2 was spent teaching the patient to self-monitor emotions and their relation to eating disorder symptoms. The patient reported that these exercises were helpful (“I learned more about my emotions”). She also noted that EABT gave her a sense of independence because “I am doing it on my own.” At the end of treatment, the patient showed improvements in body weight, emotion avoidance, and quality of life; other outcomes remained relatively unchanged from their low levels at the pre-treatment assessment (see Table 1).

DISCUSSION

This case series provides preliminary evidence that EABT, a novel psychotherapeutic intervention based on third generation behavior therapy principles, may have promise in the treatment of older adolescents and adults with AN. Of the first five patients who were offered EABT, four completed at least 90% of the therapy sessions (i.e., ≥ 22 sessions), and three showed modest weight gains without hospitalization or intensive treatment. The patients that responded to EABT (n = 3) also demonstrated improvements on several secondary outcomes including depressive and anxiety symptoms, emotion avoidance, and quality of life. These findings may suggest that EABT has utility as an outpatient intervention for older adolescents and adults with AN. However, it is important to note that weight gains among patients in this case series were no better than those documented in previous studies of brief outpatient psychotherapy for AN [see, e.g., (5)], and improvements in the cognitive correlates of disordered eating were negligible. Thus, although EABT appears to be a feasible and acceptable intervention for older adolescents and adults with AN, future research is needed to determine whether it has efficacy in ameliorating anorexic symptoms.

As one might expect in a small case series, the patients that received EABT were diverse with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics. Given interest in the idea of matching patients to specific treatments [see, e.g., (24)], it is tempting to speculate about whether EABT might be more or less effective for certain types of AN presentations, or whether there are baseline characteristics for which EABT might be recommended or proscribed. In reviewing the case series, it is clear that EABT was least effective for the most severely ill patient in the cohort (i.e., Patient # 03). However, weight gains and improvements in secondary outcomes were similar in the other three patients despite differences in age, length of illness, and co-morbid psychopathology. This may suggest that EABT is a useful intervention for a broad range of AN presentations. However, all of the patients treated successfully with EABT had AN-R, and outcomes were best for those individuals who entered treatment at higher weights. Thus, it remains to be determined whether EABT can be extended to the outpatient treatment of individuals with AN-B/P and those presenting at low weights, and whether the results from this small initial group will be replicated or improved in a larger series of patients.

In conclusion, the results of this case series indicate that EABT is feasible, acceptable, and may be efficacious in treating older adolescents and adults with AN. These promising outcomes coupled with growing interest in the utility of mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions for eating disorders (25, 26) support further work on the development of EABT. Guided by feedback from the case series patients and their therapists, we have made several changes to the EABT protocol designed to enhance the intervention. Examples include expanding the length of treatment to a minimum of 40 sessions, and building flexibility into the protocol so that therapists can increase session frequency when patients are struggling with weight loss or other eating disorder behaviors (e.g., purging). We also are interested in evaluating factors that may predict outcome following EABT. For example, it is possible that sustained weight loss early in treatment, as opposed to weight maintenance or gain, may signal a poor response to the intervention. It also is possible that EABT may be less effective for patients with a chronic course of AN. A larger pilot study is underway to address these questions, and to help determine whether the findings from this case series can be replicated or improved.

Acknowledgements

Development of EABT is supported by grant # MH82685 from the National Institute of Mental Health. We wish to thank Jill Gaskill, CRNP, Joanna Gould, MSW, Elizabeth McCabe, PhD, and Rebecca Ringham, PhD for their roles in treating the patients described in this case series.

References

- 1.Lock J, Agras WS, Bryson S, Kraemer HC. A comparison of short- and long-term family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. J J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:632–639. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000161647.82775.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulik CM, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, Lohr KN. Anorexia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:310–320. doi: 10.1002/eat.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter JC, McFarlane TL, Bewell C, Olmsted MP, Woodside DB, Kaplan AS, et al. Maintenance treatment for anorexia nervosa: A comparison of cognitive behavior therapy and treatment as usual. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:202–207. doi: 10.1002/eat.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pike KM, Walsh BT, Vitousek K, Wilson GT, Bauer J. Cognitive behavior therapy in the posthospitalization treatment of anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2046–2049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntosh VVW, Jordan J, Carter FA, Luty SE, McKenzie JM, Bulik CM, et al. Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: A randomized, controlled trial. AmJ Psychiatry. 2005;162:741–747. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treat TA, McCabe EB, Gaskill JA, Marcus MD. Treatment of anorexia nervosa in a specialty care continuum. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:564–572. doi: 10.1002/eat.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruch H. Conversations with anorexics. Basic Books, Inc.; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slade P. Towards a functional analysis of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Br J Clin Psychol. 1982;21:167–179. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1982.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. The Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt U, Treasure J. Anorexia nervosa: Valued and visible. A cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45:343–366. doi: 10.1348/014466505x53902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye W. Neurobiology of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strober M. Pathologic fear conditioning and anorexia nervosa: On the search for novel paradigms. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35:504–508. doi: 10.1002/eat.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treasure JL. Getting beneath the phenotype of anorexia nervosa: The search for viable endophenotypes and genotypes. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:212–219. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moses EB, Barlow DH. A new unified treatment approach for emotional disorders based on emotion science. Curr Dir Psychol Science. 2006;15:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:639–665. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor ME. Eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. ed. 16.0D The Guilford Press; New York: 2008. pp. 265–308. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG, Bissett RT, Pistorello J, Toarmino D, et al. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:553–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engel SG, Wittrock DA, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, Kolotkin RL. Development and psychometric validation of an eating disorder-specific health-related quality of life instrument. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:62–71. doi: 10.1002/eat.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychologist. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baer RA, Fischer S, Huss DB. Mindfulness and acceptance in the treatment of disordered eating. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2005;23:281–300. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berman MI, Boutelle KN, Crow SJ. A case series investigating acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for previously treated, unremitted patients with anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2009;17:426–434. doi: 10.1002/erv.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]