Abstract

Background and purpose

It is unclear whether delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions against implanted metals play a role in the etiopathogenesis of malfunctioning total knee arthroplasties. We therefore evaluated the association between metal allergy, defined as a positive patch test reaction to common metal allergens, and revision surgery in patients who underwent knee arthroplasty.

Patients and methods

The nationwide Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register, including all knee-implanted patients and revisions in Denmark after 1997 (n = 46,407), was crosslinked with a contact allergy patch test database from the greater Copenhagen area (n = 27,020).

Results

327 patients were registered in both databases. The prevalence of contact allergy to nickel, chromium, and cobalt was comparable in patients with and without revision surgery. However, in patients with 2 or more episodes of revision surgery, the prevalence of cobalt and chromium allergy was markedly higher. Metal allergy that was diagnosed before implant surgery appeared not to increase the risk of implant failure and revision surgery.

Interpretation

While we could not confirm that a positive patch test reaction to common metals is associated with complications and revision surgery after knee arthroplasty, metal allergy may be a contributor to the multifactorial pathogenesis of implant failure in some cases. In cases with multiple revisions, cobalt and chromium allergies appear to be more frequent.

Technological advancement in engineering and design of knee prostheses and also higher surgical standards have improved safety and prosthetic survival, but up to 20% of patients in general (Murray et al. 2014) and 12% of those in Denmark (Database 2011) are still not satisfied with the result of their knee replacement. The most common complications include aseptic loosening, pain, secondary placement of the patella component, and polyethylene failure (Database 2011, Aggarwal et al. 2014, Schairer et al. 2014).

Often, implant failure of unknown etiology involves pain and aseptic loosening. The etiopathogenesis of aseptic loosening is probably multifactorial, with many contributory factors (Sundfeldt et al. 2006, Gallo et al. 2014). It is generally agreed that particles released from wear, and perhaps corrosion, accumulate around the joint, and activate the host immune response. Macrophages contain wear particles and orchestrate local osteolysis and bone resorption at the bone-prostheses interface. It is uncertain whether delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions against implanted metals contribute to osteolysis, but a recent review article has shown that T-helper cell 1-cytokines, such as IL-2 and interferon gamma—which are expressed in metal allergy—are frequently identified in histological samples from patients (Gallo et al. 2013). In further support of this, a recent systematic review (Granchi et al. 2012) on total joint replacement showed that the prevalence of metal allergy is higher postoperatively (odds ratio (OR) = 1.5, 95% CI: 1.1–2.3) when compared to controls, and that the prevalence is even higher when patients with failed implants are compared to patients with stable total joint replacements (OR = 2.8, 95% CI: 1.1–6.7). However, it is still unknown whether metal allergy prior to implantation may be a risk factor for revision surgery or whether it is a result of implant failure resulting in secondary sensitization (Thyssen et al. 2009a).

We assessed the association between metal allergy and revision surgery of TKAs, the hypothesis being that contact dermatitis patients with metal allergy would have a higher degree of prosthetic complications following TKA than dermatitis patients without metal allergy.

Patients and methods

Study population

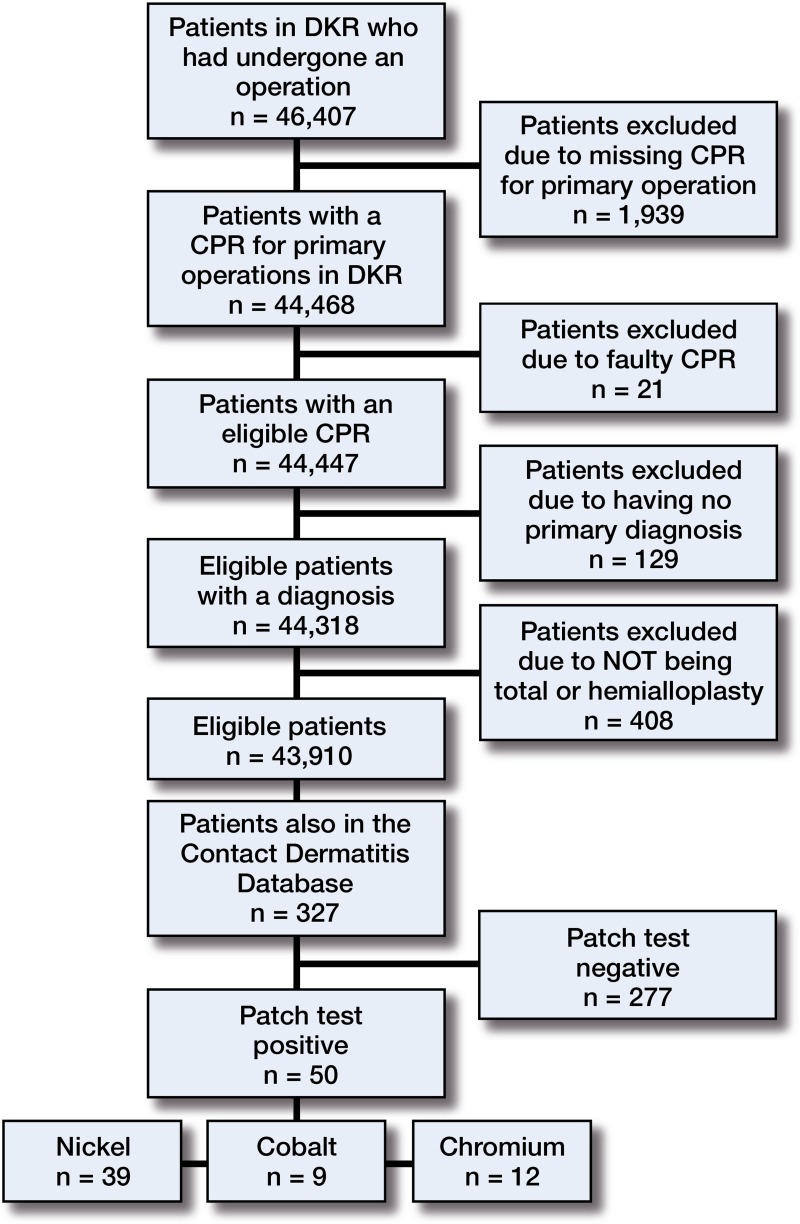

All Danes are assigned a personal identification number consisting of their 8-digit date of birth followed by an additional 4 digit identification code. These identification numbers are managed by the Central Personal Register (CPR), and allow unique, specific data extractions covering multiple registers. In this study, we crosslinked the nationwide Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register (DKAR), operated from the Common Orthopaedic Database, Center for Clinical Quality and Competence, Aarhus, Denmark, with a contact allergy database (CAD) from the greater Copenhagen area, which is operated from Gentofte Hospital, Denmark. The DKAR receives data from all public Danish hospitals that perform TKA and revisions and also from some private clinics (Pedersen et al. 2012). The CAD contains patch test data from consecutive patients with dermatitis who have been evaluated for contact allergy at the tertiary department of dermatology, Gentofte Hospital, which mainly serves the greater Copenhagen area. We crosslinked the 2 databases for the period 1979–2013. From the CAD, we extracted metal allergy data from 27,020 patients who underwent patch testing between 1977 and 2013. From the DKAR, we identified 46,407 patients for the period 1997–2009. 43,910 of them were eligible for the study, as they had undergone knee surgery and had been correctly registered in the DKAR (Figure 1). After crosslinking, 327 patients were identified who had undergone both metal allergy patch testing and primary TKA, and 253 of them had been patch-tested before their TKA operation.

Figure 1.

The process of selection of the study population.

Patch testing

Patch testing was performed with the European Baseline Series using Finn chambers (8 mm; Epitest Ltd., Oy, Finland) on Scanpor tape (Norgesplaster A/S, Vennesla, Norway). Only results for nickel, cobalt, and chromium testing were used for this study. For the entire study period, nickel sulfate (5%), cobalt chloride (1%), and potassium dichromate (0.5%) were used in petrolatum. According to international guidelines, the patches were applied on the upper back and were occluded for 48 h. Readings were done at standardized time intervals after application: 48 h, 72 h, 96 h, and 7 days. Any reactions were scored using the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group (ICDRG) criteria (Wilkinson et al. 1970). Negative, “irritant”, and doubtful readings were regarded as negative reactions, whereas 1+, 2+, and 3+ reactions were categorized as positive.

Statistics

Continuous data were categorized into categorical variables using SPSS for Windows release 19.0. The chi-square test was used to test for possible differences between categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test was used if the expected frequency of any of the cells was less than 5. The level of statistical significance was set at 5% (p = 0.05). Associations were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with corresponding 95% CI.

Ethics

The project was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (diary entry number 2007-58-015). It was approved on December 3, 2010 with planned completion extended until the February 18, 2015.

Results

In general, patient characteristics were similar in those who were registered in the DKAR only and those who were registered in both the CAD and the DKAR, except that there was a significantly lower prevalence of women in the DKAR only (62% vs. 72%; p = 0.001 (p-values are not shown in Table 1)). However, this difference was to be expected, as the proportion of women is generally high in patch-tested dermatitis patients (Uter et al. 2012). 2,806 patients (6.4%) underwent revision surgery, but only 32 of these (1.1%) were in the CAD group. Aseptic loosening, pain, instability, and infection were common causes of revision surgery in both groups. A higher proportion of patients who experienced pain without loosening was observed in the 327 patients who had also been patch-tested (4% vs. 1.5% in those who had not; p = 0.002)—but overall, the causes of revision and prevalence of postoperative complications were similar in the 2 groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who underwent primary total knee replacement and revision surgery between 1997 and 2009

| Patients from the DKAR (2013) (n = 43,910) n (%) | Dermatitis patients from the DKAR a (n = 327) n (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 27,367 (62.3) | 234 (71.6) | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) |

| Age groups: | |||

| 10–49 | 2,224 (5.1) | 15 (4.6) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) |

| 50–59 | 7,383 (16.8) | 68 (20.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1) |

| 60–69 | 14,721 (33.5) | 111 (33.9) | 1 (0.8–1.2) |

| 70–79 | 14,161 (32.2) | 108 (33.0) | 1 (0.8–1.2) |

| > 79 | 5,421 (12.3) | 25 (7.6) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) |

| Primary diagnosis: | |||

| Primary idiopathic osteoarthritis | 36,694 (83.6) | 281 (85.9) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) |

| Secondary osteoarthritis | 4,190 (9.5) | 24 (7.3) | 1.3 (0.9–2) |

| Sequelae of trauma | 1,029 (2.3) | 3 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.8–8.1) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1,389 (3.2) | 16 (4.9) | 0.6 (0.9–1.1) |

| Sequelae of other arthritides | 211 (0.5) | 0 | |

| Hemophilia | 21 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.02–1.2) |

| Other diagnoses | 376 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.4–5.7) |

| Type of operation: | |||

| Total arthroplasty | 40,773 (92.9) | 301 (92.0) | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) |

| Unicompartmental arthroplasty | 3,137 (7.1) | 26 (8.0) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) |

| Previously operated in the same knee | 13,261 (30.2) | 86 (26.3) | 1.2 (1–1.6) |

| Cause of revision: | |||

| Aseptic loosening | 883 (2.0) | 7 (2.1) | 0.9 (0.4–2) |

| Pain but no loosening | 669 (1.5) | 13 (4.0) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

| Instability of the knee | 587 (1.3) | 9 (2.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) |

| Deep infection | 622 (1.4) | 7 (2.1) | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) |

| Secondary insertion of patella component | 340 (0.8) | 5 (1.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) |

| Polyethylene failure, patella/tibia | 223 (0.5) | 3 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) |

| Other | 443 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 3.3 (0.5–23.7) |

| Postoperative complications | 2,023 (4.6) | 11 (3.4) | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) |

Patients who were examined for metal allergy at Gentofte Hospital

Comparison of patients from the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register (DKAR) (reference category) and patients from the DKAR who were also examined for metal allergy at Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen (chi-square test). Fisher’s exact test was used when the expected frequency in 1 of the cells was lower than 5.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of metal allergy in different populations, including adults in the general population in Copenhagen, Denmark (Thyssen et al. 2009c) and dermatitis patients at Gentofte Hospital (Thyssen et al. 2010). As expected, the prevalence of metal allergy was higher in dermatitis patients than in controls from the general population. In particular, dermatitis patients who underwent revision surgery had a lower prevalence of metal allergy than dermatitis patients with well-functioning TKA (13% vs. 16%), but this difference was not statistically significant. This was mainly explained by a lower prevalence of nickel allergy in the revised group, whereas cobalt allergy had a slightly higher prevalence (4.1% vs. 6.3%).

Table 2.

Nickel, cobalt, and chromium (+metal*) allergy stratified by patient status. Values are n (%) and (95% CI)

| n | Nickel allergy | Cobalt allergy | Chromium allergy | Metal allergya | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults from the general population (Thyssen et al. 2009c) | 3,460 | 204 (5.9) (5.2–6.8) | 8 (0.2) (0.1–0.5) | 5 (0.1) (0.1–0.3) | 345 (9.7) (9–11) |

| Dermatitis patients from between 1977 and 2009 (Thyssen et al. 2010) | 22,506 | 2,341 (10.4) (10–10.8) | 856 (3.8) (3.6–4.1) | 608 (2.7) (2.5–2.9) | Not available |

| Dermatitis patients who underwent knee arthoplasty | 327 | 39 (12) (8.9–16) | 9 (2.8) (1.5–5.1) | 14 (4.3) (2.6–7.1) | 50 (15) (12–20) |

| Dermatitis patients who underwent knee arthoplasty but not revision surgery | 295 | 37 (13) (9.2–16) | 12 (4.1) (2.3–7) | 8 (2.7) (1.4–5.3) | 46 (16) (12–20) |

| Dermatitis patients who underwent knee arthoplasty and had revision surgery | 32 | 2 (6.3) (1.7–20) | 2 (6.3) (1.7–20) | 1 (3.1) (0.6–16) | 4 (13) (5–28) |

defined as nickel, cobalt, and/or chromium allergy.

In general, revision surgery was not associated with a higher prevalence of metal allergy (Table 3). However, although the numbers are low and therefore prone to random error, there appeared to be a slightly higher prevalence of cobalt and chromium allergy in patients with 2 or more revisions relative to the controls. Regarding the specific complications in the 8 patients with 2 of more revisions, 6 were primarily operated due to osteoarthritis. As for their revision profile, which can include multiple diagnoses, 4 were revised due to pain without loosening, 4 were revised due to infection, and 3 were revised due to aseptic loosening. None of the latter 3 had any secondary diagnoses as a cause of revision. 253 (77%) of the CAD patients were patch-tested before primary knee surgery. Of these, only 5 had multiple revisions performed and had metal allergy at the same time.

Table 3.

The prevalence of metal allergy in 327 patients who underwent primary TKA and/or revision surgery. Values are n (%) and (95% CI)

| Operated once once | Reviseda (n = 32) | Revised once (n = 24) | Revised 2 or more times (n = 8) | ORa | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal allergy b | 46 (16) (12–20) | 4 (13) (5–28) | 2 (8) (2–26) | 2 (25) (7–59) | 0.8 (0.3–2) | 1 |

| Nickel allergy | 37 (13) (9–17) | 2 (6) (2–20) | 2 (8) (2–26) | 0 (0) | 0.5 (0.1–2) | 0.05 |

| Cobalt allergy | 8 (3) (1–6) | 1 (3) (1–16) | 0 | 1 (13) (2–47) | 1.2 (0.1–9.6) | 1 |

| Chromium allergy | 12 (4) (2–7) | 2 (6) (2–20) | 0 | 2 (25) (7–59) | 1.5 (0.3–7) | 0.06 |

For comparison of cases without revision and those with any revisions (chi-square test). Fisher’s exact test was used when the expected frequency in one of the cells was lower than 5.

Metal allergy was defined as a positive patch test reaction to nickel, cobalt, or chromium.

OR: odds ratio.

Discussion

This retrospective registry-based crosslink study showed that metal allergy was not associated with revision surgery, and furthermore that cases with metal allergy prior to implantation did not appear to have a higher prevalence of complications or revision surgery. Our results therefore support the hypothesis that metal allergy is neither a general risk factor for failure of TKA nor a major player in its etiopathogenesis. The study also indicated (based on a small number of patients) that those with 2 or more revisions had a higher prevalence of metal allergy, which can be explained by increased release of metals from wear and/or corrosion—resulting in secondary sensitization and possibly failure (Hallab et al. 2001). Furthermore, we found a higher incidence of metal allergy with patients who had had a revision because of unexplained pain. We cannot rule out that it was in fact metal allergy that had an important role in the etiopathogenesis of implant failure. Thus, some individuals could be more susceptible to the effect of metal allergic reactions and thereby be at particular risk when implanted with prostheses that contain metals such as nickel, cobalt, and chromium. Today there is evidence to suggest that implants, both stable and unstable, result in metal sensitization. For example, Granchi et al. (2008) recently showed that the prevalence of metal allergy was higher after TKA—either stable or loosened (no implant 20%; stable TKA 48%, p = 0.05; loosened TKA 60%, p = 0.001)—relative to controls. The most compelling cases to support an association between metal allergy and implant failure, however, come from THA patients with failed metal-on-metal joints, where metal release appears to be very high (Thomas et al. 2009). Also, it is noteworthy that cytokines normally involved in delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions have been frequently identified in histopathological samples of patients with aseptic osteolysis (Gallo et al. 2014, Gallo et al. 2013). Surprisingly, we found a lower prevalence of metal allergy in dermatitis patients who underwent (single) revision surgery than in dermatitis patients with well-functioning TKA. This was mainly due to a lower prevalence of nickel allergy in the revised group, which is likely to be explained by a cohort effect. Thus, ear and body piercings often leading to nickel allergy are uncommon in older patients, whereas younger individuals more often have piercings (Thyssen et al. 2009b). The slightly higher prevalence of cobalt allergy in those who underwent revision surgery could in fact be explained by release of cobalt from the implant.

Non-mechanical complications following arthoplasty include dermatitis, bullous skin reactions, vasculitis, pain, osteolysis (Rostoker et al. 1987, Basko-Plluska et al. 2011), and—more rarely—pseudotumor formation and ALVAL (Mikhael et al. 2009). We present selected prospective studies below to provide an overview of the association between metal allergy and complications following arthroplasty, but we emphasize that the studies were heterogeneous regarding the design, the inclusion criteria, the tests used to identify metal allergy, the follow-up period, and the primary outcome. Also, several of the studies included both THA and TKA patients. Many different prostheses are available on the market, and these are constantly changing due to advances in design and wear properties. For example, hip prostheses include metal-on-metal, metal-on-polyethylene, ceramic-on-polyethylene, and ceramic-on-ceramic implants. At present, metal-on-polyethylene is the main design used for TKA.

In a small study, 18 patients who were allergic to metal before implantation of an orthopedic device were re-evaluated several years later, but none had experienced dermatological or systemic complications (Carlsson and Moller 1989). Another study, involving 66 patients who underwent THA with metal-on-polyethylene arthroplasty and in whom patch testing was performed prior to surgery and 6–12 months afterwards, showed that few patients developed metal allergy and that none of them experienced complications (Nater et al. 1976). One study examined 92 patients with a modified lymphocyte stimulation test prior to TKA, and showed that 26% were allergic to at least one metal (nickel, cobalt, chromium, or iron) (Niki et al. 2005). After surgery, 5 patients developed allergic metal dermatitis and 2 of these underwent revision TKA, resulting in clearance of dermatitis. The authors found that chromium was the most likely metal to cause dermatitis after TKA, and concluded that routine screening for chromium and cobalt allergy could predict future metal allergy. Importantly, they emphasized that all patients with metal allergy had excellent bone growth into the implant, and were therefore revised due to dermatitis rather than loosening of the implant. A more recent study supported the notion that chromium and cobalt in particular may result in metal allergy following implantation, as the prevalence of chromium allergy increased after TKA or THA from 5% to 8% and the prevalence of cobalt allergy increased from 10% to 17% (Krecisz et al. 2012). However, a crosslink study from our group involving 356 patients showed that revision surgery was not associated with chromium or cobalt allergy (Thyssen et al. 2009a). Also, a recent study evaluating 87 patients for metal allergy prior to total joint arthroplasty showed no association between metal allergy and pain postoperatively (Zeng et al. 2014). One study showed that of 40 patients who underwent uncemented hip replacement, 12% were metal-sensitized 6 months after surgery and 18% were sensitized 36 months after surgery according to a leukocyte function test, whereas none of the patients reacted to a patch test (Vermes et al. 2013). Finally, in 72 patients undergoing TKA or THA who were patch-tested both before and after surgery, 5 patients who had initially tested negative became positive for at least 1 metal constituent of the prosthesis. Some patients were also tested using a lymphocyte transformation test (Frigerio et al. 2011).

Based on published studies that have evaluated the association between metal allergies and implant failure, different groups have argued about the value of pre-implant testing. Razak et al. (2013) performed a consensus study involving 90 British orthopedic surgeons and concluded that a prosthesis of inferior quality or design should not be implanted following a positive metal allergy screening before the operation. This conclusion represents a pragmatic approach based on the general experiences of orthopedic surgeons.

The above-mentioned systematic review from 2012 (Granchi et al. 2012) concluded that there was no certain predictive value of pre-implant metal allergy testing. Finally, a recent questionnaire study evaluated the opinion of leading patch test practitioners attending conferences in Europe and the USA (Schalock and Thyssen 2013). Here, despite a low participation rate, it became clear that there is currently no consensus on the value of pre-implant patch testing. We therefore conclude that there is currently no evidence on which to base a recommendation for pre-implant testing of arthroplasty patients in general. Even so, metal allergy may still, in theory, take part in the etiopathogenesis of implant failure and should at least be considered prior to implantation in selected cases where a suspicion of a possible strong adverse reaction is present, either from a strong personal medical history of metal reactivity or from an earlier verification of metal allergy by patch test. Advancements in prosthesis design are therefore essential, as the best current protective measure is well-produced implants with a low wear rate, reducing the particle load in the patient’s tissues—and also the potential for secondary sensitization.

The present study had limitations apart from the relatively small sample size. Firstly, the patch test may not always provide an accurate reflection of an intrinsic immune response. Some dermatologists and immunologists therefore consider the lymphocyte transformation test (LTT) to be a more specific hypersensitivity test, as it measures the proliferation of monocytes under metal ion stimulation, expressed as a stimulation index (Hallab et al. 2008). Yet, the LTT also has several weaknesses, e.g. that T-cells die quickly, that the cost is high, that inter-laboratory variation must be taken into consideration, and that there is a lack of standardization for several metals. Secondly, the allergy database only covers part of the greater Copenhagen area, and mainly serves those who have been referred from private dermatology practice. Bias may therefore have affected our results. Thirdly, we only tested for cobalt, chromium, and nickel, so other metal allergies that were not tested for could have affected the risk of complications and revisions. However, a strong point of our study was that the databases (including the CAD) covered the whole period 1977–2013. Thus, with the average lifetime of a prosthesis being > 9 years (Lozano Gomez et al. 1997), we should have covered the time frame in which metal allergy might have caused a hypersensitivity reaction, thus reducing the lifetime of the prosthesis.

While we could not confirm that a positive patch test reaction to common metals is associated with complications and revision surgery following knee arthroplasty, metal allergy may well contribute to the multifactorial pathogenesis of implant failure in selected cases. In those patients who have undergone multiple revisions, cobalt and chromium allergy appear to be more frequent. We cannot recommend pre-implantation screening for metal allergy unless there is a strong suggestion of previous adverse reactions to metal allergens in the patient’s history.

Acknowledgments

HJM, SSJ, and JPT initated the study. Data analysis was performed by HJM and JTO, and it was supervised by JPT. The article was drafted by HM, supervised by SSJ and JPT, who corrected the draft in a constructive manner. The article was then reviewed and approved by KS, TM, and JDS, who also contributed with critical comments.

Jacob Thyssen is a Lundbeck Foundation Fellow and is supported by an unrestricted grant.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Aggarwal VK, Goyal N, Deirmengian G, Rangavajulla A, Parvizi J, Austin MS. Revision total knee arthroplasty in the young patient: is there trouble on the horizon? . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:536–42. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basko-Plluska JL, Thyssen JP, Schalock PC. Cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants . Dermatitis. 2011;22:65–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Moller H. Implantation of orthopaedic devices in patients with metal allergy . Acta Derm Venereol. 1989;69:62–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Database T. D. O. C. Danish Knee Register-Yearly Report. 2011.

- Frigerio E, Pigatto PD, Guzzi G, Altmare G. Metal sensitivity in patients with orthopaedic implants: a prospective study . Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:273–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo J, Goodman SB, Konttinen YT, Raska M. Particle disease: biologic mechanisms of periprosthetic osteolysis in total hip arthroplasty . Innate Immun. 2013;19(2):213–24. doi: 10.1177/1753425912451779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo J, Vaculova J, Goodman SB, Konttinen YT, Thyssen JP. Contributions of human tissue analysis to understanding the mechanisms of loosening and osteolysis in total hip replacement . Acta Biomater. 2014;10:2354–66. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granchi D, Cenni E, Tigani D, Trisolini G, Baldini N, Giunti A. Sensitivity to implant materials in patients with total knee arthroplasties . Biomaterials. 2008;29:1494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granchi D, Cenni E, Giunti A, Baldini N. Metal hypersensitivity testing in patients undergoing joint replacement: a systematic review . J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1126–34. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B8.28135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallab N, Merritt K, Jacobs JJ. Metal sensitivity in patients with orthopaedic implants . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:428–36. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200103000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallab NJ, Caicedo M, Finnegan A, Jacobs JJ. Th1 type lymphocyte reactivity to metals in patients with total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res. 2008;6 doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krecisz B, Kiec-Swierczynska M, Chomiczewska-Skora D. Allergy to orthopedic metal implants – a prospective study . Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2012;25:463–9. doi: 10.2478/S13382-012-0029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano Gomez MR, Ruiz Fernandez J, Lopez Alonso A, Gomez Pellico L. Long-term results of the treatment of severe osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis with 193 total knee replacements . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:102–12. doi: 10.1007/s001670050035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhael MM, Hanssen AD, Sierra RJ. Failure of metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty mimicking hip infection. A report of two cases . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:443–6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DW, Maclennan GS, Breeman S, Dakin HA, Johnston L, Cambell MK, Gray AM, Fiddian N, Fitzpatrick R, Morris RW, Grant AM, Group KAT. A randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different knee prostheses: the Knee Arthroplasty Trial (KAT) . Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(1)(235):vii–viii. doi: 10.3310/hta18190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nater JP, Brian RG, Deutman R, Mulder TJ. The development of metal hypersensitivity in patients with metal-to-plastic hip arthroplasties . Contact Dermatitis. 1976;2:259–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1976.tb03044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Otani T, Yatabe T, Kondo M, Yoshimine F, Toyama Y. Screening for symptomatic metal sensitivity: a prospective study of 92 patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty . Biomaterials. 2005;26:1019–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Odgaard A, Schroder HM. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: The Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register . Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:125–35. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S30050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razak A, Ebinesan AD, Charalambous CP. Metal allergy screening prior to joint arthroplasty and its influence on implant choice: a delphi consensus study amongst orthopaedic arthroplasty surgeons . Knee Surg Relat Res. 2013;25:186–93. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2013.25.4.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostoker G, Robin J, Binet O, Blamoutier J, Paupe J, Lessana-Leibowitch M, Bedouelle J, Sonneck JM, Garrel JB, Millet P. Dermatitis due to orthopaedic implants. A review of the literature and report of three cases . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1408–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schairer WW, Vail TP, Bozic KJ. What are the rates and causes of hospital readmission after total knee arthroplasty? . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:181–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3030-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalock PC, Thyssen JP. Metal hypersensitivity reactions to implants: opinions and practices of patch testing dermatologists . Dermatitis. 2013;24:313–20. doi: 10.1097/DER.0b013e3182a67d90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundfeldt M, Carlsson LV, Johansson CB, Thomsen P, Gretzer C. Aseptic loosening, not only a question of wear: a review of different theories . Acta Orthop. 2006;77:177–97. doi: 10.1080/17453670610045902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Braathen LR, Dorig M, Aubock J, Nestle F, Werfel T, Willert HG. Increased metal allergy in patients with failed metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty and peri-implant T-lymphocytic inflammation . Allergy. 2009;64:1157–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyssen JP, Jakobsen SS, Engkilde K, Johansen JD, Soballe K, Menne T. The association between metal allergy, total hip arthroplasty, and revision . Acta Orthop. 2009a;80:646–52. doi: 10.3109/17453670903487008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Menne T, Nielsen NH, Linneberg A. Nickel allergy in Danish women before and after nickel regulation . N Engl J Med. 2009b;360:2259–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0809293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menne T, Nielsen NH, Johansen JD. Contact allergy to allergens of the TRUE-test (panels 1 and 2) has decreased modestly in the general population . Br J Dermatol. 2009c;161:1124–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyssen JP, Ross-Hansen K, Menne T, Johansen JD. Patch test reactivity to metal allergens following regulatory interventions: a 33-year retrospective study . Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:102–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uter W, Aberer W, Armario-Hita JC, et al. Current patch test results with the European baseline series and extensions to it from the ‘European Surveillance System on Contact Allergy’ network, 2007–2008 . Contact Dermatitis. 2012;67:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2012.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermes C, Kuzsner J, Bardos T, Than P. Prospective analysis of human leukocyte functional tests reveals metal sensitivity in patients with hip implant . J Orthop Surg Res. 2013;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DS, Fregert S, Magnusson B, et al. Terminology of contact dermatitis . Acta Derm Venereol. 1970;50:287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Feng W, Li J, Lu L, Ma C, Zeng J, Li F, Qi X, Fan Y. A prospective study concerning the relationship between metal allergy and post-operative pain following total hip and knee arthroplasty . Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2231–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]