Abstract

Background and purpose

There is no consensus on which type of shoulder prosthesis should be used in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We describe patients with RA who were treated with shoulder replacement, regarding patient-reported outcome, prosthesis survival, and causes of revision, and we compare outcome after resurfacing hemi-arthroplasty (RHA) and stemmed hemi-arthroplasty (SHA).

Patients and methods

We used data from the national Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry and included patients with RA who underwent shoulder arthroplasty in Denmark between 2006 and 2010. Patient-reported outcome was obtained 1-year postoperatively using the Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder index (WOOS), and rates of revision were calculated by checking revisions reported until December 2011. The patient-reported outcome of RHA was compared to that of SHA using regression analysis with adjustment for age, sex, and previous surgery.

Results

During the study period, 167 patients underwent shoulder arthroplasty because of rheumatoid arthritis, 80 (48%) of whom received RHA and 34 (26%) of whom received SHA. 16 patients were treated with total stemmed shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), and 24 were treated with reverse shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA). 130 patients returned a completed questionnaire, and the total mean WOOS score was 63. The cumulative 5-year revision rate was 7%. Most revisions occurred after RHA, with a revision rate of 14%. Mean WOOS score was similar for RHA and for SHA.

Interpretation

This study shows that shoulder arthroplasty, regardless of design, is a good option in terms of reducing pain and improving function in RA patients. The high revision rate in the RHA group suggests that other designs may offer better implant survival. However, this should be confirmed in larger studies.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) often leads to destruction of the shoulder joint and functional impairment (Harris 1990, Levy et al. 2004, Trail and Nutall 2002). Shoulder arthroplasty is an established treatment in severe cases where medical and/or surgical treatment with synovectomy has failed. Previous studies have found substantial reduction in pain postoperatively in patients with RA, regardless of the choice of prosthesis, whereas the reported effect on shoulder function has varied (Levy et al. 2004, Sperling et al. 2007, Trail and Nutall 2002, Guery et al. 2006, Holcomb et al. 2010). There are different surgical options: total stemmed shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), reverse shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA), stemmed shoulder hemi-arthroplasty (SHA), or resurfacing shoulder hemi-arthroplasty (RHA). Many patients experience complicating rotator cuff pathology, which should be considered in the choice of prosthesis (John et al. 2010, Ekelund and Nyberg 2011, Young et al. 2011).

It remains unclear whether the prosthesis design influences the outcome. The advantages of RHA are minimal bone resection, short procedure time, a low risk of periprosthetic fracture, and its easy accessibility for revision (Levy et al. 2001, 2004). The disadvantages are difficulties with correct anatomical fitting, especially in cases with flattening of the humeral head with large osteophytes or poor bone quality (Al-Hadithy et al. 2012, Mechlenburg et al. 2013). RHA has been used frequently in the treatment of RA since the early 1980s, but the functional outcome has only been reported in small case series and never in comparative studies of revision (Levy et al. 2001, 2004, Jonsson et al. 1986).

Here we describe patients with RA who were treated with shoulder replacement, regarding patient-reported outcome, prosthesis survival, and causes of revision, and we compare outcome after RHA and SHA.

Patients and methods

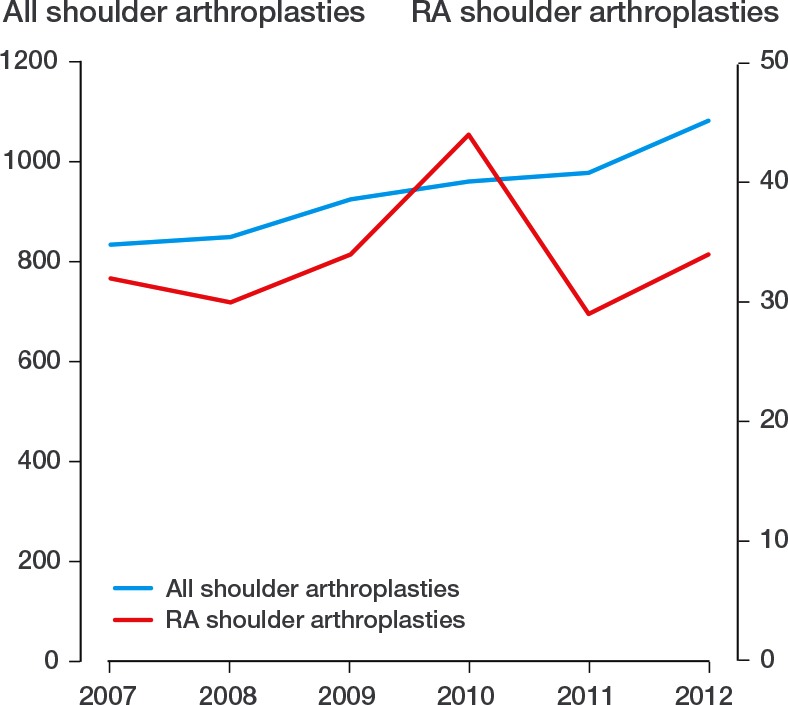

The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry (DSR) has collected information on patients treated with shoulder arthroplasty since 2004. The annual number of arthroplasties registered increased slightly during the study period, whereas the number of patients with the diagnosis rheumatoid arthritis remained stable (Figure 1). Registration is mandatory for hospitals and private clinics, and is completed by the surgeon (for both primary prostheses and revisions). We compared data with the national patient registry, which revealed that 90% of all procedures had been registered between January 2006 and December 2010, consistent with a required minimum registration level of 90% (Lynge et al. 2011, DSR annual report 2013).

Figure 1.

All shoulder arthroplasties and RA shoulder arthroplasties, 2007–2012

Outcome measures

Outcome assessment included patient-reported outcome and revision rate. Patient-reported outcome was obtained by regular post 1-year postoperatively using the Danish version of Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder index (WOOS) (Rasmussen et al. 2013).The score is percentage of optimal. Both non-responders and responders with incomplete questionnaires were sent a postal reminder.

Revision was defined as removal, exchange, or the addition of any component. Rates of revision were calculated using revisions reported to the DSR until December 2011. In the analysis of patient-reported outcome, only patients with a completed questionnaire were included. In cases of revision or death within the first year, WOOS score was registered as missing. In cases of revision or death after 1 year, the score was registered in the analysis of WOOS one year postoperatively.

Statistics

The patient-reported outcome (WOOS) was converted into a continuous scale to compare differences between prosthesis types. We defined a 10-point/10-percent difference as clinically relevant. A regression model (ANOVA) for prosthesis types was used to estimate differences in patient-reported outcome, and to adjust for possible confounders (age, sex, and previous operations).

Rates of revision were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method from data reported to the DSR. Inclusion of patients with bilateral procedures violates the assumption of independence, but it has been argued to be of little practical importance regarding analysis of implant survival (Ranstam et al. 2011). We included all operations in order to obtain higher statistical power.

The level of statistical significance was set at 5% (p = 0.05). Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 17.0.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (journal no. 2007-58-0015).

Results

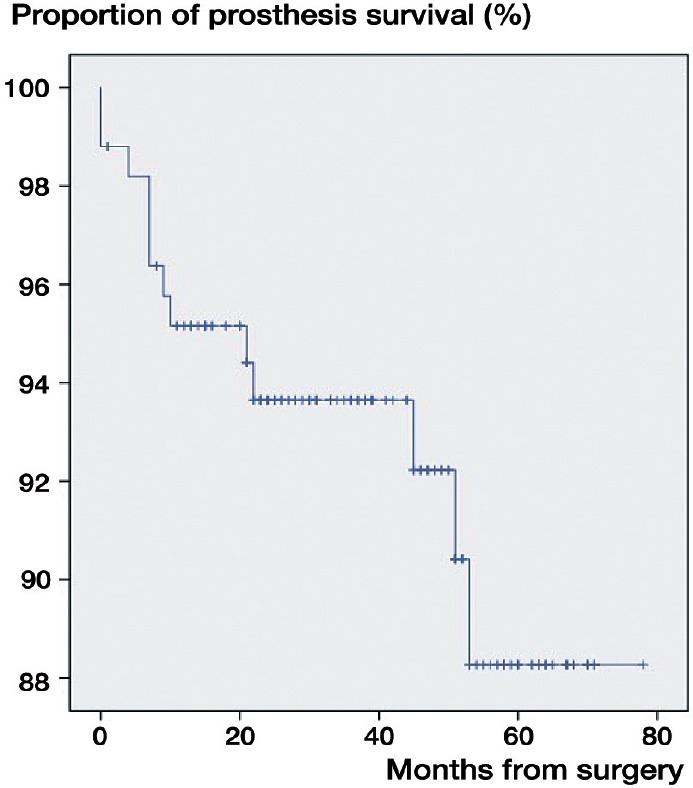

In the study period, 167 patients (80% of them women) had the primary diagnosis reumatoid arthritis. Mean age was 65 (SD 13) years, and 43 (26%) had bilateral surgery. There were 13 TSAs (10%), 62 RHAs (48%), 34 SHAs (26%), and 20 rTSAs (15%)—and 1 (1%) was unaccounted for (Tables 1 and 2). The cumulative 5-year revision rate was 7% (Figure 2). The causes of revision were implant loosening (n = 4), rotator cuff problems (n = 3), glenoid attrition (n = 1), and periprosthetic fractures (n = 1). In 3 patients, the cause of revision was missing.

Table 1.

Demography of arthroplasty designs

| All | TSA | rTSA | RHA | SHA | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 65 | 65 | 74 | 63 | 65 | 0.3 |

| Female | 133 | 14 | 19 | 62 | 37 | 0.8 |

| Previous surgery | 16 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Non-responder | 37 | 3 | 4 | 18 | 12 | 0.2 |

| Total | 167 b | 16 | 24 | 80 | 46 |

RHA vs. SHA by t-test and chi-squared test.

1 missing

Table 2.

Distribution of prosthesis brands and prosthesis designs

| Prosthesis design |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHA | TSA | RHA | rTSA | |

| Global advantage | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Bigliani | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Bigliani Standard | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Global FX | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nottingham | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neer (Monoblock) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aequalis-Tornier | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neer (Modular) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anden | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Copeland | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 |

| Global Cap | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Delta Extend | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Delta Mark 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Anatomical shoulder | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Figure 2.

Prothesis survival in the RA population treated with shoulder arthroplasty

For analysis of patient-reported outcome, we included the 130 patients who returned a completed WOOS questionnaire (78%). Missing and incomplete WOOS questionnaires accounted for 22 of the other patients, 7 patients had died within 1 year, and 8 had been revised within 1 year. Mean WOOS score was 63 (SD 25) (Table 2). 16 patients were treated with TSA. 13 of them returned a questionnaire, and they had a mean WOOS score of 75 (SD 18). In the 20 patients who were treated with rTSA, we found a mean WOOS score of 60 (SD 25) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patients with complete WOOS scores. Values are mean (SD)

| TSA | rTSA | RHA | SHA | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOOS score | 60 (25) | 75 (18) | 61 (27) | 58 (21) | 63 (25) |

| No. of patients | 13 | 20 | 62 | 34 | 129 a |

1 missing

Comparison of RHA and SHA

Of the 80 patients who received RHAs, 62 responded. The mean WOOS score was 61 (SD 27), as compared to 58 (SD 21) after SHA, where 34 of the 46 patients responded. The revision rate after RHA was statistically significantly higher than that after SHA (Table 1).

Of the 167 original patients with RA, 12 revisions were performed (7%). 1 of the revisons was performed in a patient treated with SHA (2%) and the other 11 revisions were performed in patients treated with RHA (14%).

Discussion

In RA patients with severe arthritis of the shoulder, we found that hemi-arthroplasty—and RHA especially—was the preferred choice of shoulder arthroplasty. The indications for using RHA and SHA are the same, but the design of RHA with humeral head surface replacement with a short central peg only calls for minimal bone resection, and is a less invasive procedure. However, RHA is not suitable for use in a severely damaged joint with major bone loss or poor bone quality precluding fixation (Levy et al. 2004).

We found no statistically or clinically significant difference in WOOS score between SHA and RHA. This could indicate that the postoperative WOOS score is unaffected by the choice of prosthesis. However, patients treated with TSA should theoretically represent those with glenoid damage, and those treated with rTSA should represent patients over the age of 70, with either rotator cuff damage or after revision of shoulder arthroplasty, suggesting a poorer preoperative status. Thus, the RA patients treated with RHA and SHA are those with less advanced disease. Without a preoperative WOOS status for comparison, it could be hypothesized that both rTSA and TSA could provide a greater improvement in WOOS score and patients with severe glenoid destruction may benefit from total shoulder replacement. On the assumption that patients receiving RHA and SHA are comparable at baseline, our findings suggest that postoperative WOOS score is unaffected by the choice of prosthesis. In summary, the results from Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry indicate that the choice of prosthesis does not influence patient-reported outcome.

Levy et al. (2004) compared RA patients treated with total resurfacing arthroplasty and those treated with TSA, and found no difference in pain relief and range of motion. They suggested that total resurfacing arthroplasty may be a better choice than TSA because RA patients often experience involvement of several joints, and with ipsilateral elbow prostheses, the use of total resurfacing arthroplasty could minimize stress fracture between stems in the mid-part of the humeral shaft.

Barlow et al. (2014) compared RA patients treated with HA and TSA, and found no clinically significant difference in improvement. They made a distinction between patients with a damaged or intact rotator cuff. In the group with rotator cuff damage, they found no difference in pain relief or function between patients treated with TSA and those treated with HA. However, in patients with an intact rotator cuff, they found 2 advantages after TSA: improved pain relief and function and a reduced risk of revision (see also Sperling et al. 2007). Our findings confirm the higher revision rate in the HA group, where we found 12 revisions (7%), 11 of which were in patients treated with RHA (which alone had a revision rate of 14%). Barlow et al. (2014) found a 10-year revision rate of 7% for the TSA group and 12% for the HA group. They found the most common reasons for revision in the TSA group to be glenoid loosening and infection, whereas for the HA group the main reason was glenoid arthritis. The reported causes of revision in our material were mainly loosening (n = 4) and rotator cuff problems (n = 3), but also glenoid attrition (n = 1) and fracture (n = 1). Over-stuffing of the joint does not alone count as a cause of revision, but is included in “others”.

In a large Norwegian registry study, Fevang et al. (2009) reported an increasing use of shoulder arthroplasty for all diagnoses except RA, where a decline was observed. In 15 of 439 cases, they reported that the primary cause of revision in RA patients treated with HA was pain (Fevang et al. 2009).

Our study had the advantage of a large and unselected patient material, resulting in high degree of external validity and statistical power. However, the lack of detailed reports on revision and/or WOOS scores challenges the accuracy of the results. The missing or incomplete WOOS questionnaires resulted in exclusion of 37 patients (22% of the total). Preoperative WOOS score, rotator cuff status, and the reason for a particular choice of prosthesis are all valuable, but missing information. The lack of preoperative WOOS may have added limitations to the study, since patients with poor rotator cuff status could have a worse WOOS score preoperatively than those with an intact rotator cuff, which would in turn lead to a wider range of improvement in WOOS score postoperatively, assuming that one existed.

We found a high revision rate in the group treated with HA, and especially in those treated with RHA. It is possible that surgeons are more likely to revise RHA simply because the surgical intervention itself is less extensive than revising the other prosthesis. It is also possible that RHA represents a first choice of prosthesis—one that is more easily converted to another prosthesis in case of complications. In addition, revision rate as an indicator of postoperative status does not take into account the group of RA patients who live with pain and reduced function but where an indication for revision cannot be found.

Possible future prostheses in the treatment of RA include pyrocarbon prostheses, stemless prostheses (total and hemi), and prosthesis designs that are easily converted from conventional anatomic prostheses to a reverse design by replacing the modular component. The pyrocarbon prosthesis is associated with bio-friendly wear characteristics that could result in less stress on cartilage and the glenoid, compared to metals and ceramics. This prosthesis is thought to be a good option for younger patients, especially those with arthritis. The effect has not yet been documented, but any new implants will be monitored by the registry.

Until 2011, procedures in Denmark were performed in 32 hospitals, but since 2012 joint replacement in RA has been restricted to 13 departments (DSR annual report 2013). The rationale was to increase volume and thereby the level of experience in fewer surgeons, regarding this relatively small and possibly decreasing patient group. There is inevitably a difference in the surgeons’ previous training and level of experience in each procedure, and therefore a possible difference in outcome. Centralization may result in better operative results—through more consistent allocation to the best-documented prosthesis design—and better surgery, performed in experienced hands (Jämsen et al. 2013, Christie et al. 2011).

In summary, most RA patients with advanced disease who undergo shoulder arthroplasty experience improvement in pain and function. The cumulative revision rate was 7%, with the main reasons being loosening, rotator cuff problems, glenoid attrition, and periprosthetic fracture. Revisions only occurred in the hemi-arthroplasty patients, and by far most frequently in those treated with RHA (with a 14% revision rate). The reason for this is unclear, but it is possible that the high revision rate in RHA reflects accessibility for revision or steps of operative treatment where RHA represents the first, least invasive choice that is easily converted into another prothesis design.

Acknowledgments

PCTV carried out the literature research, data processing, and analysis, and also drafted the manuscript. JVR contributed to the design of the study and statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript. SB assisted with the literature research, and contributed to the study design and drafting of the manuscript. BSO helped to draft the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Al-Hadithy N, Domos P, Sewell MD, Naleem A, Papanna MC, Pandit R. Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty of the shoulder for osteoarthritis: results of fifty Mark III Copeland prosthesis from an independent center with four-year mean follow-up . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:1776–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow JD, Yuan BJ, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Cofield RH, Sperling JW. Shoulder arthroplasy for rheumatoid arthritis: 303 consecutive cases with minimum 5-year follow-up . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:791–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie A, Dagfinrud H, Ringen HO, Hagen KB. Beneficial and harmful effects of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a Cochrane review . Rheumatology. 2011;50:598–602. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekelund A, Nyberg R. Can reverse shoulder arthroplasty be used with few complications in rheumatoid arthritis? . Clin Orthop. 2011;469:2483–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1654-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years . J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88(8):1742–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fevang BS, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen A, Furnes O. Risk factors for revision after arthroplasty 1825 shoulder arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register . Acta Orthop. 2009;80(1):83–91. doi: 10.1080/17453670902805098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris E D. Rheumatoid arthritis. Pathophysiology and implications for therapy . N Engl Med. 1990;322:1277–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005033221805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb JO, Herbert J, Mighell MA, Dunning PE, Pupello DR, Pliner MD, Frankle MA. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:1076–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jämsen E, Virta LJ, Hakala M, Kauppi MJ, Malmivaara A, Letho M. The decline in joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a concomitant increase in the intensity of anti-rheumatic therapy . Acta Orthop. 2013;84:331–7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.810519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John M, Pap G, Angst F, Flury MP, Lieske S, Schwyer HK, Simmen BR. Short-term results after reversed shoulder arthroplasty (Delta III) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and irreparable rotator cuff tear . Inter Orthop. 2010;34:71–7. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0733-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson E, Eglund N, Kelly I, Rydholm U, Lidgren L. Cup arthroplasty of the reuatoid shoulder . Acta Orthop Scand. 1986;57:542–6. doi: 10.3109/17453678609014790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy O, Copeland SA. Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty of the shoulder. 5- to 10-year results with the Copeland Mark-2 prothesis . J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83:213–21. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b2.11238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy O, Funk L, Sforza G, Copeland SA. Copeland surface replacement arthroplasty of the shoulder in rheumatoid arthritis . J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86:512–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish national patient register . Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):30–3. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo IK, Griffin S, Kirkley A. The development of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for osteoarthritis of the shoulder: The Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index . Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(8):771–8. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechlenburg I, Amstrup A, Klebe T, Jacobsen SS, Teichert G, Stilling M. The Copeland resurfacing humeral head implant does not restore humeral head anatomy. A retrospective study . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133:615–9. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J, Kärrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Mäkelä K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A, Mehnert F, Furnes O. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data. I. Introduction and background . Acta Orthop. 2011;82:253–7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.588862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen JV, Jakobsen J, Olsen BS, Brorson S. Translation and validation of the Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index – the Danish version . Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2013;4:49–54. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S50976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS. Total shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis of the shoulder: Results of 303 consecutive cases . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):683–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry. Annual report 2013. https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/3/4703_dsr_årsrapport2013_final22052013.pdf Available from. Date last accessed April 1st 2014.

- Trail IA, Nutall D. The results of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis . J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84(8):1121–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b8.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AA, Smith MM, Bacle G, Moraga C, Walch G. Early results of reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis . J Bone Joint Surg. 2011;93:1915–23. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]