Abstract

Background and purpose

There is no consensus on the treatment of proximal humerus fractures in the elderly.

Patients and methods

We conducted a systematic search of the medical literature for randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials from 1946 to Apr 30, 2014. Predefined PICOS criteria were used to search relevant publications. We included randomized controlled trials involving 2- to 4-part proximal humerus fractures in patients over 60 years of age that compared operative treatment to any operative or nonoperative treatment, with a minimum of 20 patients in each group and a minimum follow-up of 1 year. Outcomes had to be assessed with functional or disability measures, or a quality-of-life score.

Results

After 2 independent researchers had read 777 abstracts, 9 publications with 409 patients were accepted for the final analysis. No statistically significant differences were found between nonoperative treatment and operative treatment with a locking plate for any disability, for quality-of-life score, or for pain, in patients with 3- or 4-part fractures. In 4-part fractures, 2 trials found similar shoulder function between hemiarthroplasty and nonoperative treatment. 1 trial found slightly better health-related quality of life (higher EQ-5D scores) at 2-year follow-up after hemiarthroplasty. Complications were common in the operative treatment groups (10–29%).

Interpretation

Nonoperative treatment over locking plate systems and tension banding is weakly supported. 2 trials provided weak to moderate evidence that for 4-part fractures, shoulder function is not better with hemiarthroplasty than with nonoperative treatment. 1 of the trials provided limited evidence that health-related quality of life may be better at 2-year follow-up after hemiarthroplasty. There is a high risk of complications after operative treatment.

Proximal humerus fractures are common, and most of them occur in elderly patients. The incidence in Finland was reported to be 105 per 105 person-years in 2002 (Palvanen et al. 2006), but this varies depending on the geographic area (Hagino et al. 1999, Court-Brown and Caesar 2006). The number of proximal humerus fractures has increased during the last few decades. As the population ages, the number of proximal humerus fractures would be expected to increase further (Palvanen et al. 2006).

Proximal humerus fractures are often displaced and comminuted in the elderly. The treatment method varies between countries, hospitals, and different surgeons. The popularity of plate fixation has increased in Finland with no real evidence to support it (Huttunen et al. 2012).

The literature on proximal humerus fractures is vast, but there has been little high-quality research comparing different treatments. There have been a few randomized controlled trials (RCTs), but rather than giving exact answers, these studies appear to have raised even more questions. Because previous systematic reviews (Lanting et al. 2008, Sproulet al. 2011, Brorson et al. 2012) and the latest Cochrane review (Handoll et al. 2012) have not included the RCTs published in recent years, we wanted to evaluate all of the relevant literature and to summarize the current evidence-based knowledge on the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. Moreover, the above reviews did not concentrate on the troublesome osteoporotic fractures. We assessed the effect of operative treatment on function and/or disability and complications of different treatments in elderly patients with proximal humeral fractures.

Materials and methods

We conducted a systematic search of the following electronic databases, without language restrictions, covering the years 1946 to 2012: Ovid MEDLINE and the Scopus database, which includes Embase. The last search was carried out on April 30, 2014. The search terms were: “shoulder fractures”, “proximal humeral fracture”, and “rehabilitation, surgery, therapy”. The detailed MESH terms are given in the appendix (see Supplementary data).

The abstracts of the publications retrieved were manually checked and relevant publications were selected for further analysis. Reviews, trial protocols, and retrospective studies were excluded. In the next phase, full articles were obtained for all potentially relevant papers, to determine whether they fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The PICOS principle was used to determine the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). These phases were performed independently by 3 authors. Any discrepancies regarding the inclusion criteria were settled by negotiation between the authors.

Table 1.

PICOS criteria for the trials included

| Patients: | Age 60 years or older with a 2-, 3-, or 4-part proximal humerus fracture due to recent trauma |

| Intervention: | Any operative treatment (at least 20 patients in each treatment group) |

| Control: | Any treatment (at least 20 patients in each treatment group) |

| Outcome: | Any functional or disability score and/or any quality-of-life score after a minimum follow-up of 1 year |

| Study setting: | Randomized, controlled trial or controlled clinical trial |

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data in the studies were evaluated by 1 author using a predefined data sheet. The extraction was checked independently by 2 other authors; thus, each citation was checked at least twice. We collected information on study design and descriptive data, such as the fracture classification used, types of treatment in the intervention and control groups, group sizes, drop-out rates, and patient demographics; the effects of treatment, including primary and secondary outcomes, reported complications, and reoperation rate; and study quality, including the criteria for the risk of bias. The risk of bias was assessed as suggested by Furlan et al. (2009). The risk of bias was considered to be low when 6 or more criteria out of 12 were met, and the risk was rated as high when less than 6 out of 12 criteria were met. During this assessment, we contacted each main author (n = 8) in order to obtain additional information and clarification if there was inadequate reporting in the publication. 5 of the authors replied to queries regarding missing information on randomization, allocation, and baseline group similarities. With the additional information from the authors, the analysis of bias risk was complete. In addition, the potential conflicts of interests reported by the authors were documented.

Results

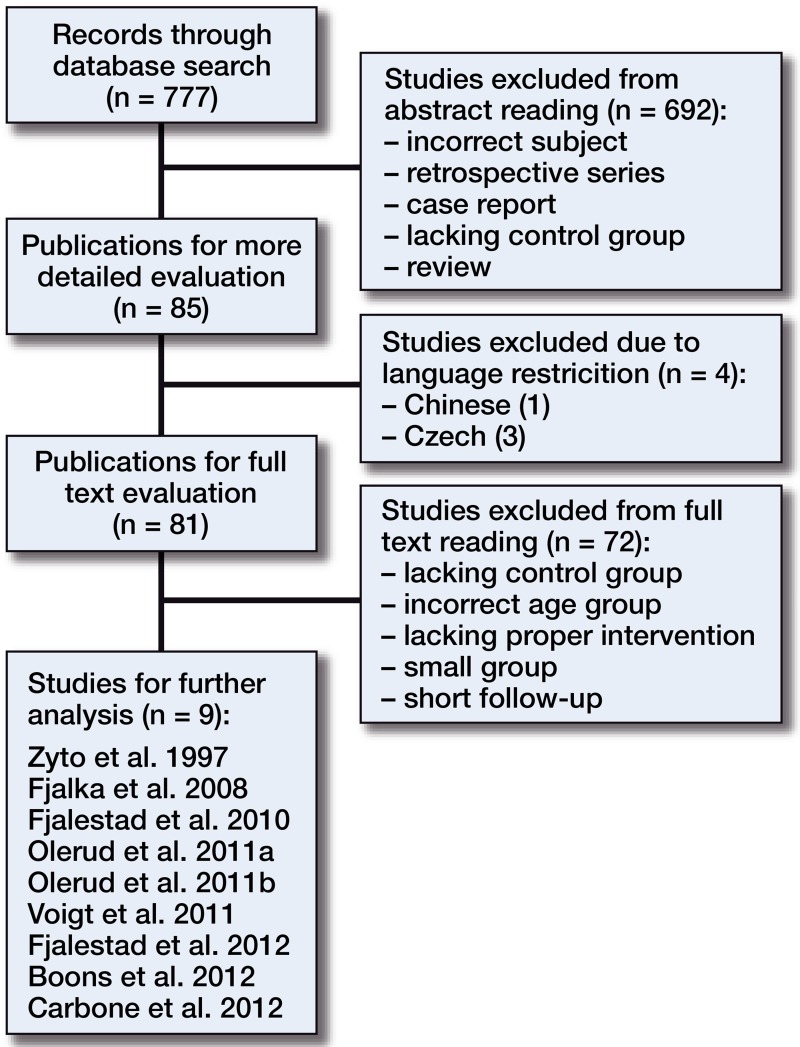

After eliminating duplicates, the database search resulted in 777 abstracts. 9 papers met the inclusion criteria and were accepted for review (Figure 1 and Table 2). 692 abstracts did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded, due to being retrospective in design or to lacking a control group.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of publications investigated, from search for abstracts to final analysis.

Table 2.

Study designs

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zyto 1997 | Sweden | RCT | 3(-4) | Tension band (20) | Nonoperative (20) | 12 | 40/38 | 73 | 75 | 2 | |

| Fialka 2008 | Austria | RCT | 4 | 11-C | Hemiarthroplasty | Hemiarthroplasty | 12 | 40/35 | 74 | 73 | 5 |

| (Epoca (20)) | (HAS (20)) | ||||||||||

| Fjalestad 2010 | Norwayb | RCT | 3-4 | 11-B2, 11-C2 | Plating a (25) | Nonoperative (25) | 12 | 50/48 | 72 | 73 | 2 |

| Olerud 2011a | Sweden | RCT | 4 | Hemiarthroplasty | Nonoperative (28) | 24 | 55/49 | 76 | 78 | 6 | |

| (Global FX (27)) | |||||||||||

| Olerud 2011b | Sweden | RCT | 3 | Plating (Philos (30)) | Nonoperative (30) | 24 | 60/53 | 73 | 75 | 7 | |

| Voigt 2011 | Germany | RCT | 3-4 | Plating (humeral | Plating (Philos (31)) | 12 | 56/48 | 76 | 72 | 8 | |

| suture plate (25)) | |||||||||||

| Fjalestad 2012 | Norwayb | RCT | 3-4 | 11-B2, 11-C2 | Plating a (25) | Nonoperative (25) | 12 | 50/48 | 72 | 73 | 2 |

| Boons 2012 | Netherlands | RCT | 4 | Hemiarthroplasty | Nonoperative (25) | 12 | 50/47 | 76 | 80 | 3 | |

| (Global FX (25)) | |||||||||||

| Carbone 2012 | Italy | CCT | 3-4 | MIROS pinning (31) | Traditional pinning (27) | 24 | 58/52 | 78 | 81 | 6 |

AAuthor

BCountry

CDesign

DNeer

EAO-OTA

FIntervention (n at baseline)

GControl (n at baseline)

HFollow-up, months

INo. of patients at baseline/follow-up

JMean age (intervention group)

KMean age (control group)

LDrop-out, n

Nonspecific LCT AO-type locking plate.

Both publications are from the same population.

The study populations involved 409 patients. 8 studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 1 was a controlled clinical trial (Carbone et al. 2012). In all trials, the patients had a recent 3- or 4-part fracture based on Neer’s classification (Neer 1970). 6 trials compared operative treatment and nonoperative treatment. Voigt et al. (2011) compared monoaxial and polyaxial constructions in locking plates, Fialka et al. (2008) compared 2 different prostheses, and Carbone et al. (2012) compared 2 different pinning operations. Zyto et al. (1997) compared use of a tension band and conservative treatment. In 3 studies (Fjalestad et al. 2010, Olerud et al. 2011b, Fjalestad et al. 2012), locking plates were compared to nonoperative treatment for 3- and 4-part fractures. 2 trials (Olerud et al. 2011a, Boons et al. 2012) compared prosthesis and nonoperative treatment for 4-part fractures. The study designs and patient populations are given in Table 2. Table 3 summarizes the primary and secondary outcomes.

Table 3.

Functional results of the trial. Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise stated

| Primary outcome measure |

Secondary outcome measure |

Adjacent outcome measure |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Intervention | Control | p-value | Intervention | Control | p-value | Intervention | Control | p-value |

| Zyto 1997 | CS: 60 (19) | 65 (15) | > 0.05 | ||||||

| Fialka 2008 | ICS: 70 (38–102)b | 46 (15–80)b | 0.001 | CS: 52 (20–80)b | 33 (8–68)b | na | |||

| Fjalestad 2010 a | CD: 35 (28–43)b | 33 (26–40)b | 0.6 | ASES: 15 (12–18)a | 16 (13–18)b | 0.7 | |||

| Olerud 2011a | EQ: 0.81 (0.12) | 0.65 (0.27) | 0.02 | CS: 48 (16) | 50 (21) | 0.8 | DASH: 30 (18) | 37 (21) | 0.3 |

| Olerud 2011b | CS: 61 (19) | 58 (23) | 0.6 | DASH: 26 (25) | 36 (27) | 0.2 | EQ: 0.70 (0.34) | 0.59 (0.35) | 0.3 |

| Voigt 2011 | SST: 8 (3) | 10 (2) | 0.3 | DASH: 18 (16) | 16 (12) | 1.0 | CS: 73 | 81 | > 0.05 |

| Fjalestad 2012 a | 15D: 0.84 (0.11) | 0.82 (0.08) | 0.4 | ||||||

| Boons 2012 | CS: 64 (16) | 60 (18) | 0.4 | SST: 25 (8–100) | 23 (0–92) | 0.6 | VAS12: 23 (1–65)c | 25 (1–93) c | 0.7 |

| Carbone 2012 | CS: 60 | CS: 52 | 0.02 | SSV: 90 | 73 | 0.02 | |||

CS = Constant Score;

ICS = Individual Constant Score determined by comparing the operated shoulder to the patient’s unaffected shoulder in percent;

CD = Constant Score difference at 12 months, and to reduce the influence of age, the difference between the scores for the injured and

uninjured shoulders was used;

ASES = American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Shoulder Score

EQ = Euroqol-5D

DASH = Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand

SST = Simple Shoulder Test

SSV = Subjective Shoulder Value

VAS12 = Visual Analogue Scale at 12 months, mean (range)

Both publications are from the same population.

Threshold values

Range

3 of the 9 studies had a high risk of bias. They lacked appropriate randomization (e.g. sealed envelopes, random number generation, and/or concealment of allocation) or did not report baseline characteristics in an appropriate way. The remaining 6 studies had a low risk of bias (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

Outcomes and complications

Tension band

Zyto et al. (1997) reported the results of a comparison of tension band and nonoperative treatment after 1-year follow-up. The Constant score (CS) was 60 and 65, respectively, at 1 year, but the difference was reported as not being significant. A 10-point difference in CS has been considered to be clinically significant in rotator-cuff tears (Kukkonen et al. 2013).

Zyto et al. (1997) reported a total of 8 complications among patients. In the intervention group, the surgical site infection rate was 2 out of 19. In 1 case, the K-wire penetrated the glenohumeral joint and another patient experienced a pulmonary embolus. In the later phase, 2 patients in the intervention group developed osteoarthritis (1 patient after non-union) and 2 patients in the control group developed osteoarthritis.

Pinning

Carbone et al. (2012) reported the results of a comparison of MIROS pinning and traditional pinning after 2 years of follow-up. The MIROS was described as “a new percutaneous pinning device allowing correction of angular displacement and stable fixation of fracture fragments”. The mean CS was 60 for MIROS pinning and 52 for traditional pinning, and the mean subjective shoulder evaluation value was 90 vs. 73. Both results were statistically significant in favor of MIROS pinning, but they lacked clinical significance.

Carbone et al. (2012) also reported 3 complications in 28 patients in the MIROS group and 7 complications in 26 patients in the traditional pinning group, including 4 pin-track infections. They did not report any reoperations.

Locking plate

Fjalestad et al. (2010, 2012) compared locking plate and nonoperative treatment in 3- and 4-part fractures. The primary outcome was a difference in CS (CSD 12) at 12 months; in order to reduce the influence of age, the difference between the scores of the injured and uninjured shoulder was used. No statistically significant or clinically significant differences were found in any of the following outcomes. The mean CSD12 was 35 and 33 in the surgical and nonoperative treatment groups, respectively, and the mean American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons shoulder score (ASES) was 15 and 16. In assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL), mean 15D in the surgery group was 0.84 and it was 0.82 in the nonoperative group.

Olerud et al. (2011b) found similar CS in operative and nonoperative groups for 3-part fractures (61 vs. 58). Disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH) (operative 26 vs. nonoperative 36; p = 0.2) and Euroqol-5D (EQ-5D; operative 0.70 vs. nonoperative 0.59; p = 0.3) were similar between groups at 2 years.

Voigt et al. (2011) found no significant differences between polyaxial and monoaxial constructions in locking plates in the simple shoulder test (8.6 vs. 9.7; p = 0.3), DASH (18 vs. 16; p = 1.0), and CS (73 vs. 81; p > 0.05)

Fjalestad et al. (2010, 2012) reported 1 hardware failure, 7 screw cut-outs, and 2 deaths in 3 months in the surgery group. 4 of the 25 patients needed a reoperation. 1 of the nonoperatively treated patients was operated on later. Olerud et al. (2011b) reported screw penetrations in 5 of 30 cases in the primary postoperative period, and 3 additional screw penetrations at 4 months. 1 case of primary postoperative infection was reported, and 1 patient in the nonoperative group had non-union. Altogether, 4 patients died (2 from each group), for reasons not related to surgery. Reoperations were required for 9 of 30 patients in the locking plate group during the 2-year follow-up period. Voigt et al. (2011) reported 6 complications in the intervention (polyaxial) group (n = 20) and 8 in the control (monoaxial) group (n = 28). Reoperations were performed in 6 and 4 cases.

Hemiarthroplasty

In the studies comparing hemiarthroplasty with nonoperative treatment, all the patients had 4-part fractures. Olerud et al. (2011a) found that the operative group had better mean EQ-5D (0.81) than the nonoperative group (0.62), which was clinically and statistically significant (p = 0.02). However, mean DASH (30 vs. 37; p = 0.3) and CS (48 vs. 50; p = 0.8) were not significant at the 2-year follow-up. Boons et al. (2012) found no statistically significant differences in mean values for CS (operative treatment 64 vs. nonoperative treatment 60), the simple shoulder test (25 vs. 23), or the visual analog scale (VAS) at 12 months (23 vs. 25).

Fialka et al. (2008) compared 2 prostheses: Epoca (Depuy Synthes) and HAS (Stryker). The individual Constant score (CSindiv) was determined by comparing the operative shoulder to the patient’s unaffected shoulder. The CSindiv was 70% and 46% for the Epoca and HAS (p = 0.001), and absolute CS was 52 vs. 33 (p-value not reported) at the 1-year follow-up, with both results favoring the Epoca prosthesis.

Olerud et al. (2011a) reported 1 non-union in their nonoperative group (n = 28). Of all 55 patients, 5 died—3 in the operative group (n = 27) and 2 in the nonoperative group (n = 28), and none fracture-related. 3 patients in the operative group required reoperation, and 1 patient in the nonoperative group with non-union received operative treatment. Boons et al. (2012) reported 4 tuberculum malpositions and 2 greater tubercle non-unions in the operative group. 5 cases of non-union were reported in the nonoperative group (n = 25). 1 patient required reoperation, and the other patient in the nonoperative group was operated on at 13 months. Fialka et al. (2008) reported 2 infections in the operative group (n = 18); these were treated nonoperatively with antibiotics.

Discussion

8 RCTs from 7 study populations and 1 controlled clinical trial—all published between 1946 and April 30, 2014—fulfilled our inclusion criteria. In these trials, there were no significant differences in functional outcomes between surgical treatment with a tension band and nonoperative treatment. Moreover, the complication rate was greater with operative treatment. With locking plate systems, operations did not result in substantial improvement in function or HRQoL scores compared to nonoperative treatment. Furthermore, patients treated operatively had high complication rates (10–29%) and high reoperation rates (16–30%).

In 4-part fractures, HRQoL measured with the EQ-5D was better, both clinically and statistically, with fracture prosthesis than with nonoperative treatment. However, the reliability of EQ-5D in the assessment of HRQoL in patients with a proximal humeral fracture is controversial. Olerud et al. (2011c) reported good internal and external responsiveness of EQ-5D in patients with a proximal humeral fracture. In contrast, Slobogean et al. (2010) and Skare et al. (2013) found a substantial ceiling effect, which limits the reliability of this instrument. Thus, the results of Olerud et al. (2011a) must be interpreted with caution. In addition, they did not find any significant differences in mean functional shoulder scores between the 2 groups. Up to 20% of patients in the nonoperative group had non-union, whereas tuberculum malposition was detected in 16% of the patients in the operative group. Non-union and tuberculum malposition compromise clinical results and lead to poor range of movement (ROM).

Comparison of surgical alternatives

The functional outcomes favored the Epoca prosthesis over the HAS prosthesis. Both groups had very few complications. However, 1-year follow-up is too short for detection of loosening, detection of wear, and determination of prosthesis survival. Some studies have addressed the treatment of complicated proximal humerus fractures with reverse prostheses (Cuff and Pupello 2013, Cazeneuve and Cristofari 2014), but there have been no high-quality trials to match the inclusion criteria of our review. No differences were found in function or complication rate between patient groups in whom monoaxial or polyaxial screws were used with the locking plate. Comparing MIROS pinning and traditional pinning, MIROS gave better functional results and a lower complication rate. All of the results comparing 2 surgical alternatives are from publications with a high risk of bias.

We realize that the criteria used in our review are tight, excluding trials that may have potential clinical significance, but our primary aim was to collect evidence for treatment of elderly patients with proximal humerus fracture. Although we initially limited inclusion to patients aged 60 years or more, we decided to include 3 papers with some younger patients (Fialka et al. 2008, Olerud et al. 2011a, b). However, the mean age of the patients in these studies was 74–77 years. Leaving these 3 rather good-quality trials out of the analysis would have left us with too few trials to draw any conclusions from, so they were included according to the PRISMA recommendations acknowledging the need for an iterative process in some systematic reviews (Moher et al. 2009). Another limitation may be related to uncertain classifications systems, and therefore unknown patient recovery for distinct fracture types (Majed et al. 2011). 3 publications had a high risk of bias. As the publications in this review were heterogeneous regarding patient groups, interventions, and outcome measures, a meta-analysis was not justified.

The Cochrane library published the latest systematic review on this subject in December 2012 (Handoll et al. 2012). They concluded that, “There is insufficient evidence to inform the management of these fractures”. The difference with our analysis is that we set the age limit at 60 years and older, and we had criteria for the appropriate group sizes. Furthermore, our analysis includes papers by Fjalestad et al. (2012), Boons et al. (2012), and Carbone et al. (2012), which were published after the Cochrane review. According to the trial registries (clinicaltrials.com, controlled-trials.com), there are currently 5 trials enrolling patients to compare operative and nonoperative treatment.

In summary, there are too few trials for a solid evidence base. Furthermore, 3 of the publications had a high risk of bias, but these papers assessed differences between 2 operative treatments and did not provide evidence for the main question: whether to use operative or nonoperative treatment. However, there is some weak evidence in favor of nonoperative treatment over surgery with locking plate systems and tension banding. 2 trials have provided weak to moderate evidence that for 4-part fractures, shoulder function is not better with hemiarthroplasty than with nonoperative treatment. One of the trials has provided limited evidence that health-related quality of life may be better at 2-year follow-up after hemiarthroplasty. With high complication rates for all operative treatments, these should not be considered to be the gold standard in the treatment of proximal humerus fractures.

Supplementary data

Table 4 and Appendix are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 7918.

Acknowledgments

AL, VL, and TF performed the data extraction. All the authors took part in data analysis and in drafting of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Boons HW, Goosen JH, van Grinsven S, van Susante JL, van Loon CJ. Hemiarthroplasty for humeral four-part fractures for patients 65 years and older: a randomized controlled trial . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:12, 3483–91. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2531-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brorson S, Rasmussen JV, Frich LH, Olsen BS, Hrobjartsson A. Benefits and harms of locking plate osteosynthesis in intraarticular (OTA Type C) fractures of the proximal humerus: a systematic review . Injury. 2012;43(7):999–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone S, Tangari M, Gumina S, Postacchini R, Campi A, Postacchini F. Percutaneous pinning of three- or four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in elderly patients in poor general condition: MIROS(R) versus traditional pinning . Int Orthop. 2012;36(6):1267–73. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1474-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. Grammont reversed prosthesis for acute complex fracture of the proximal humerus in an elderly population with 5 to 12 years follow-up . Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(1):93–7. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review . Injury. 2006;37(8):691–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2050–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fialka C, Stampfl P, Arbes S, Reuter P, Oberleitner G, Vecsei V. Primary hemiarthroplasty in four-part fractures of the proximal humerus: randomized trial of two different implant systems . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjalestad T, Hole MO, Jorgensen JJ, Stromsoe K, Kristiansen IS. Health and cost consequences of surgical versus conservative treatment for a comminuted proximal humeral fracture in elderly patients . Injury. 2010;41(6):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjalestad T, Hole MO, Hovden IA, Blucher J, Stromsoe K. Surgical treatment with an angular stable plate for complex displaced proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial . J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(2):98–106. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31821c2e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M, Editorial Board C B RG 2009 method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group . Spine. 2009;34(18):1929–41. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagino H, Yamamoto K, Ohshiro H, Nakamura T, Kishimoto H, Nose T. Changing incidence of hip, distal radius, and proximal humerus fractures in Tottori Prefecture . Japan. Bone. 1999;24(3):265–70. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ, Rollins KE. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults . Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000434.pub3. CD000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen TT, Launonen AP, Pihlajamaki H, Kannus P, Mattila VM. Trends in the surgical treatment of proximal humeral fractures - a nationwide 23-year study in Finland . BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen J, Kauko T, Vahlberg T, Joukainen A, Aarimaa V. Investigating minimal clinically important difference for Constant score in patients undergoing rotator cuff surgery . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1650–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanting B, MacDermid J, Drosdowech D, Faber KJ. Proximal humeral fractures: a systematic review of treatment modalities . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1):42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majed A, Macleod I, Bull AM, Zyto K, Resch H, Hertel R, et al. Proximal humeral fracture classification systems revisited . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement . Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2009;62(10):1006–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer CS., 2nd Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;6;52:1077–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Hemiarthroplasty versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 4-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011a;20(7):1025–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 3-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011b;20(5):747–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olerud P, Tidermark J, Ponzer S, Ahrengart L, Bergstrom G. Responsiveness of the EQ-5D in patients with proximal humeral fractures . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011c;20(8):1200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palvanen M, Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J. Update in the epidemiology of proximal humeral fractures . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;442:87–92. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000194672.79634.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skare O, Liavaag S, Reikeras O, Mowinckel P, Brox JI. Evaluation of Oxford instability shoulder score, Western Ontario shoulder instability index and Euroqol in patients with SLAP (superior labral anterior posterior) lesions or recurrent anterior dislocations of the shoulder . BMC research notes. 2013;6:273. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobogean GP, Noonan VK, O’Brien PJ. The reliability and validity of the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, EuroQol-5D, Health Utilities Index, and Short Form-6D outcome instruments in patients with proximal humeral fractures . J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(3):342–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sproul RC, Iyengar JJ, Devcic Z, Feeley BT. A systematic review of locking plate fixation of proximal humerus fractures . Injury. 2011;42(4):408–13. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt C, Geisler A, Hepp P, Schulz AP, Lill H. Are polyaxially locked screws advantageous in the plate osteosynthesis of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly? A prospective randomized clinical observational study . J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(10):596–602. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318206eb46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zyto K, Ahrengart L, Sperber A, Tornkvist H. Treatment of displaced proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients . J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(3):412–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b3.7419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.