Abstract

Using a rich longitudinal dataset, we examine the relationship between teen fertility and both subsequent educational outcomes and HIV related mortality risk in rural South Africa. Human capital deficits among teen mothers are large and significant, with earlier births associated with greater deficits. In contrast to many other studies from developed countries, we find no clear evidence of selectivity into teen childbearing in either schooling trajectories or pre-fertility household characteristics. Enrolment rates among teen mothers only begin to drop in the period immediately preceding the birth and future teen mothers are not behind in their schooling relative to other girls. Older teen mothers and those further ahead in school for their age pre-birth are more likely to continue schooling after the birth. In addition to adolescents’ higher biological vulnerability to HIV infection, pregnancy also appears to increase the risk of contracting HIV. Following women over an extended period, we document a higher HIV related mortality risk for teen mothers that cannot be explained by household characteristics in early adulthood. Controlling for age at sexual debut, we find that teen mothers report lower condom use and older partners than other sexually active adolescents.

Keywords: Teenage childbearing, Education, HIV, Mortality, South Africa

1. INTRODUCTION

Teenage childbearing is seen as a serious social problem and remains a source of concern in most of the world and particularly in developing countries where it is most common. In South Africa, despite considerable decline in total fertility rates since the 1970s, the percentage of women giving birth in their teens remains high and stable. The United Nations Population Division (2010) estimates that in 2007 the adolescent birth rate in South Africa was 54 per 1000 women aged 15 to 19. This rate is much higher among African and Coloured teens and in rural areas (Garenne, Tollman and Kahn 2000; Camlin, Garenne and Moultrie 2004; Marteleto, Lam and Ranchhod 2006; Moultrie et al. 2008; Moultrie and McGrath 2007).

From a policy perspective it is important to know whether high levels of teen fertility have a negative impact on women’s human capital, which in turn could have a negative impact on their employment, their earnings, and the well-being of their children. Not only may early childbearing disrupt schooling and ultimate educational attainment, but there are morbidity and mortality risks associated with unprotected sex and pregnancy in a high HIV prevalence environment, particularly for adolescents.

The consequences of teen fertility are difficult to evaluate, as the large and highly contentious literature on teen fertility in the United States has demonstrated (see Ribar 1999; Hotz, McElroy and Sandes 2005 and Ashcraft and Lang 2006 for reviews of this literature). Although early motherhood is correlated with adverse health and social outcomes, establishing causality between teen fertility and adult socioeconomic wellbeing is far from straight forward. While there are reasons to believe that early childbearing can curtail human capital investments, it is also possible that young mothers are a select group that would have attained low levels of human capital even if their first birth had been postponed until adulthood. Researchers have applied a range of techniques in the attempt to identify the causal effect of teen childbearing. The approaches include controlling for as many observable characteristics as available (McElroy 1996), sisters and twins fixed effects (Geronimus and Korenman 1992; Holmlund 2005; Webbink, Martin and Visscher 2011), and quasi-experimental methods (Hotz, McElroy and Sandes 1998, 2005; Bronars and Grogger 1994; Ashcraft and Lang 2006; Fletcher and Wolfe 2008) including instrumental variables procedures (Ribar 1999; Klepinger, Lundberg and Plotnick 1999) and propensity score matching methods (Levine and Painter 2003; Lee 2010). While most US studies find a negative relationship between teenage childbearing and educational attainment and labor market outcomes, there is no agreement over the magnitude of the effects and some analyses find no harmful or even positive effects (Hotz et al. 2005).

Empirical evidence on the socioeconomic consequences of teen childbearing in developing countries is scarce and South Africa is no exception. Madhavan and Thomas (2005) find a negative relationship between early childbearing and schooling using South Africa census data, but point out that it is difficult to give the results a causal interpretation. Similarly, Grant and Hallman (2008) find a strong association between grade repetition and out of school periods with later pregnancy and pregnancy related school dropouts but causality cannot be established. Marteleto, Lam and Ranchhod (2008) use a combination of retrospective and prospective data from the Cape Area Panel Study (CAPS) to investigate how early life characteristics affect young-age childbearing and the factors facilitating school enrolment after childbearing. They find that young mothers who were weaker students prior to giving birth were less likely to enrol in school subsequent to giving birth. However, a significant proportion of young mothers managed to continue with their studies. This is particularly the case among African girls but it less common among Coloureds and whites. Using a propensity score weighted regression approach and a combination of retrospectively and prospectively collected CAPS data, Ranchhod et al. (2011) find that while accounting for pre-fertility characteristics substantially reduces the negative association between teen childbearing and poor educational outcomes, estimates of the effect of a teen birth remain large and significant, particularly for Africans.

Our analysis of teenage childbearing is in a context of extremely high HIV and AIDS prevalence. A national survey in 2003, found 15.5% of 15 to 24 year old women to be HIV positive (Pettifor et al. 2005). The interaction of biological and social factors place young sexually active women at higher risk of HIV acquisition than older women. Pregnancy further increases this risk, not only because pregnancies reflect unprotected sex practices in an environment of high risk but also because a number of studies indicate that during pregnancy the risk of contracting HIV rises significantly.

Young women are at comparatively higher risk of HIV acquisition than older women because their immature cervix and vaginal mucosa are more vulnerable to HIV infection (Diers 2002; Fogel 2011). A number of studies from sub-Saharan Africa document that earlier sexual debut is associated with higher HIV risk (Pettifor et al. 2004; Ghebremichael, Larsen and Painstil 2009). Teen mothers may be even more vulnerable to HIV infection than other sexually active teens engaging in unprotected sex for a number of reasons.

Firstly, a number of studies indicate that pregnant women are at significantly higher risk of HIV acquisition than non-pregnant women (Gray et al. 2005; Moodley et al. 2009; Mugo et al. 2011, among others). The elevated risk of infection could be the consequence of sexual behavior or biological changes during pregnancy. Using data from Uganda, Gray et al. (2005) show that pregnancy more than doubles the risk of acquiring HIV. These authors are able to control for sexual behavior and identify hormonal or immunological changes during pregnancy as the probable cause of increased risk. This is consistent with Walter et al. (2011) who provide evidence of immunological changes during pregnancy. Mugo et al. (2011) follow serodiscordant couples from seven African countries and also find HIV acquisition risk to be more than twice as high during pregnancy. They conclude that behavioral factors related to being pregnant are important in explaining the increased risk. Moodley et al. (2009) studied 2377 South African women who tested HIV negative at their first antenatal visit. The women were retested between 36 and 40 weeks’ gestation. HIV incidence during pregnancy was found to be four times higher than estimates for the non-pregnant population. They found no association between behavioral factors and risk of HIV acquisition.

Secondly, in various settings teenage pregnancy is associated with greater age differences between adolescent girls and their sexual partners (Jewkes et al. 2001; Manlove, Terry-Humen and Ikramullah 2006; Baumgartner et al. 2009; Darroch, Landry and Oslak 1999). In their matched case control study of over 500 adolescents in a township in Cape Town, Jewkes et al. (2001) found teenage pregnancy to be associated with teenage girls having older partners, a higher probability of coerced first sex and episodes of violence during the relationship. HIV prevalence peaks about five years earlier for women than men (Pettifor et al. 2005). Young women with older sexual partners are therefore likely to be at higher risk of contracting HIV than those with partners of the same age (Ott et al. 2011). Power inequalities in relationships are also reinforced by substantial age differences between young women and their partners making it more difficult to negotiate safe sexual practices and increasing the likelihood of violence (Jewkes, Morrel and Christofides 2009; Chimbindi et al. 2010; Leclerc-Madala 2008 and the references therein). Genital lesions and sores as a result of sexual coercion and violence may increase vulnerability to HIV infection (Diers 2002). There is evidence from several studies in sub-Saharan Africa that larger age disparities are associated with higher risk of HIV infection (Pettifor et al. 2005; Kelly et al. 2003; Leclerc-Madlala 2008; Luke 2003; Gregson et al. 2002 among others).

Due to data limitations, HIV risk and mortality is an area that has received very little attention in the literature on teen childbearing. Our data offer a unique opportunity to follow women over an extended period and see whether indeed teen mothers are at risk for higher HIV related mortality. To our knowledge, there are no international or South African studies documenting the extent to which early childbearing is associated with higher mortality risk in environments with high HIV prevalence.

There is considerable public debate and media interest in the consequences of teen pregnancy in South Africa. Much of this debate is fuelled by the perceived perverse incentives created by the child support granti (Moultrie and McGrath 2007). During the 2008 election campaign, president Jacob Zuma proposed that teenage mothers be separated from their babies and “taken to colleges and forced to get an education so that they can be in a position to look after themselves” (The Times 2008). More recently the Western Cape government proposed a plan to reward schoolgirls who don’t get pregnant to counteract the perceived lure of income from the child support grant (Cape Times 2010).

The goal of this analysis is to add to the small body of empirical evidence and advance our understanding of the human capital consequences of early childbearing in South Africa. We examine the relationship between teen fertility and both subsequent educational outcomes and mortality risk. We use a rich longitudinal dataset from the Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) that allows us to control for multiple characteristics of the mothers and their households at early ages before childbearing and to follow adolescents over an extended period to investigate mortality in early adulthood. In the developing world longitudinal surveys of the size, frequency and length of ACDIS are extremely rareii. While we may not be able to definitively establish causality, ACDIS offers much better data than has previously been available to study the links between fertility and schooling and mortality in South Africaiii.

We document large and significant human capital deficits among teen mothers. Women who have their first birth before the age of 20 have both worse educational outcomes and higher mortality risk than other women. Within the teen years fertility timing matters, with earlier births associated with greater educational deficits and higher mortality rates. Relative to their peers who delay childbearing till after their teens, women who had their first child before the age of 17 are, on average, almost one year behind and 26 percentage points more likely to have dropped out of high school by age 20. In contrast, older teen mothers who had their first child between the ages of 17 and 19 are about 0.3 years behind other women. We take advantage of longitudinal data to assess the extent to which pre-fertility characteristics can explain the negative association between early childbearing and education. In contrast to many other studies from developed countries, we find no clear evidence of selectivity into teen childbearing in either schooling trajectories or pre-fertility household characteristics. Enrolment rates among teen mothers only begin to drop in the period immediately preceding the birth and future teen mothers are not behind in their schooling relative to other girls at age 12 or 13. In addition, pre-fertility household characteristics do not appear to be predictive of future teen childbearing. The longitudinal data not only allow us to investigate the timing of falling behind but also to examine the factors associating with continuing school after the birth. Younger teen mothers are the most likely to dropout of high school. Girls who were further ahead in school for their age prior to the birth are more likely to continue their education.

We follow women over an extended period and document higher mortality risk before the age of 30 for teen mothers. This differential in mortality rates cannot be explained by household characteristics in early adulthood and is robust to variations in the time period over which we follow these women. The majority of deaths are AIDS-related. Early teen childbearing is associated with even higher mortality risk than a birth in the late teens. Teen mothers are significantly less likely to have used condoms at last sex and have, on average, older partners. While age at sexual debut is also correlated with risky sexual behavior, controlling for age at sexual debut does not explain differential condom use and partner age gaps between teen mothers and other sexually active adolescents.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the data and presents rates of teen childbearing. Section 3 documents the association between early childbearing and poor educational outcomes and then turns to examine the impact of teen childbearing on human capital attainment. Section 4 examines the relationship between teen childbearing and mortality. Section 5 concludes.

2. DATA AND RATES OF TEEN CHILDBEARING

The data for this analysis come from the Africa Centre Demographic Surveillance Area (ACDSA) which follows approximately 90,000 individuals in 11,000 households in the south of Umkhanyakude District in KwaZulu-Natal. The size of the area is around 438 km2, it is mostly rural but includes a township and peri-urban sections. The information system was started in 2000 and it covers all individuals that are members of a household located in the site, even if they live outside the surveillance area. Baseline data on individuals include age, sex, relationship to the head of the household, and retrospective birth histories in the case of women. Since January 1, 2000, each household in this site has been visited twice a year to update information on fertility, deaths, changes in marital status, moves within the area, and migration in and out of it. Additionally, detailed household and individual socio-economic data have been collected in nine different waves of Household Socio-Economic Survey (HSE), between 2001 and 2012. These data include information on household infrastructure and asset ownership and, among others, on school enrollment, educational attainment and employment status of household members.

Childbirth information is collected in a number of ways. Upon first registration, a full retrospective birth history is gathered for every woman aged 15 to 49. At subsequent biannual household visits any new pregnancy triggers an interview with the woman about the details of the pregnancy, including the final outcome. An additional source of pregnancy information is the annual women’s health survey that includes a question asking whether the woman has ever been pregnant. All three sources of pregnancy information require that the woman herself be interviewed whereas core demographic data and HSE data are collected from a knowledgeable household informant. As such, there is a small minority of cases where HSE data are available but we are unable to determine whether the woman has given birth or whether she gave birth before her twentieth birthday. We use all retrospective and prospective data to construct an indicator of teenage childbearing that equals one if the woman gave birth to a live child while she was below 20 years of age and zero otherwise and we explicitly control for missing data.

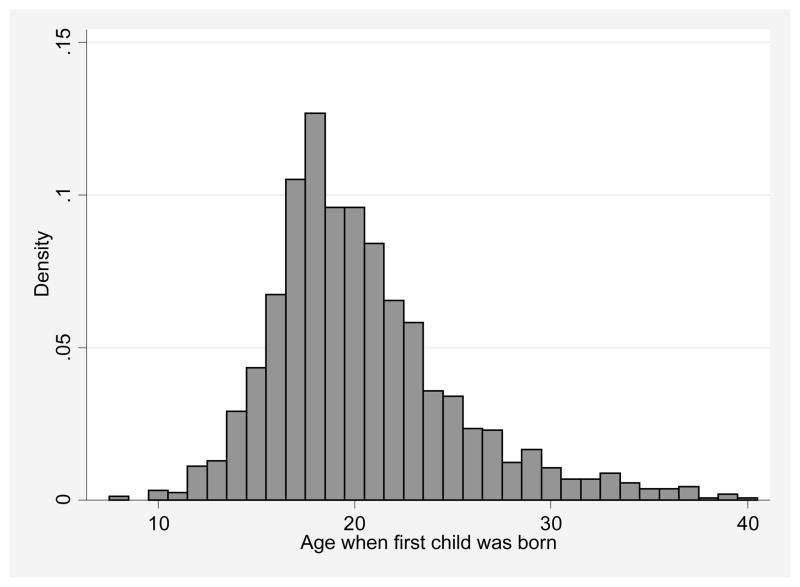

Rates of teen childbearing in the ACDSA are high relative to the rest of South Africaiv with around 46% of resident women aged 20 to 50 having their first birth before the age of 20. The prevalence of teenage childbearing appears fairly consistent across age cohorts. Figure 1 presents the distribution of the mother’s age at the birth of her first child for resident women aged 35 to 40 years of age at HSE round 5 (2007). The vast majority (95%) of resident women have given birth at least once by the age of 35. Almost half (48%) of these women had their first birth before they were 20 years of age. The majority (66%) of teenage births are in the late teens (17 to 19 years of age). There are a handful of births at very young ages, possibly due to data errors. By the age of 21, two thirds (65%) of women had given birth. Similar to elsewhere in South Africa, birth intervals in the ACDSA are long (Moultrie and Timaeus 2002). In contrast to findings from the Agincourt demographic surveillance site (Garenne et al. 2000), we do not find substantial differences in the interval between first and second births between teen and older mothers. Early childbearing is associated with higher parity. Among resident women aged 35 to 40, teen mothers had on average 1.3 children more than non-teen mothers.

Figure 1.

Mother’s age when first child was born for resident women aged 35 to 40 at HSE 5 (2007)

It is important to note that in the case of South Africa in general and the population of the ACDSA in particular, teenage childbearing is almost universally out of wedlock or regular partnership (Hosegood, McGrath and Moultrie 2009). The ACDSA has low levels of marriage and age of first marriage is high in line with the trends at the provincial and national levels. Hosegood et al. (2009) estimate that the proportion of women in a marital or regular partnership whose partner is a member of the same household has declined from 55% in 2000, to 51% in 2003, and 42% in 2006. These reductions in marriage rates have not been accompanied by a strong transition towards non-marital cohabiting unions.

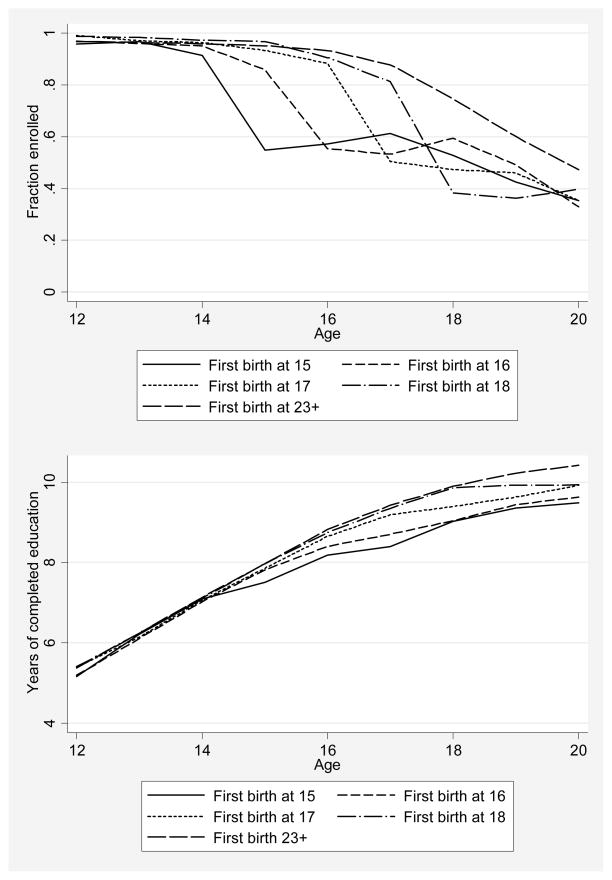

3. EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES AND TEEN CHILDBEARING

Figure 2 summarizes the association between early childbearing and educational disadvantage over time. The left panel shows the mean years of completed education by birth cohort separately for women who had their first birth before age 17, between the ages of 17 and 19, between the ages of 20 and 22 and after the age of 22. The right panel of Figure 2 shows the proportion of women in each cohort who have graduated from high school separately by age at first birth. For all cohorts in our data, women who had the first birth earlier have completed significantly fewer years of education and are less likely to have completed high school than older mothers. The gap in educational attainment between younger mothers and older mothers appears to narrow slightly for younger cohorts. The disadvantage of teen mothers with respect to completion of high school, however, remains fairly consistent across birth cohorts. On average, the youngest mothers are 26 percentage points less likely to complete high school and attain 2.8 years less education than the oldest mothers. The educational gaps between early teen, older teen and non-teen mothers of different cohorts that we observe in our data are very similar to those found using nationally representative data (Branson, Ardington and Leibbrandt 2012).

Figure 2. Years of completed education and high school completion by cohort and age at first birth for resident women.

Notes to Figure 2: Sample is resident women born between 1955 and 1985 and observed in any of HSE 1 to 9. Where women were observed multiple times, the first observation was used. In order to reflect final educational attainment, only observations where the women were at least 25 years of age were included.

Figure 2 provides clear evidence of the ongoing negative association between teenage childbearing and education. This does not, however, establish whether teenage childbearing has a causal effect on women’s human capital accumulation. Teen mothers may have had lower educational attainment even if they had not given birth in their teens. Early socioeconomic conditions, family characteristics and other variables may simultaneously affect the probability of being a teen mother and investments in education. It is possible that teen mothers are different from older mothers for reasons other than early childbearing. Longitudinal data – where we observe the teen mother before and after the birth – allow us to evaluate alternative explanations for the human capital deficits apparent in Figure 2. While we may not be able to definitively establish causality, we can use the longitudinal data to control for pre-pregnancy characteristics, examine the timing of when girls fall behind and to investigate the determinants of returning to school after the birth. We can also employ sibling (same mother) fixed effect models to compare outcomes of sisters who did and did not give birth in their teens.

In order to control for pre-birth characteristics we restrict our sample to resident women aged 20 in the last three HSE rounds (HSE6 to HSE9). We further restrict our sample to women who were also observed in an earlier HSE round, when they were between 11 and 13 years oldv. In cases where women were observed multiple times between ages 11 and 13, we use information from the most recent observation. We exclude from the sample the two women who had already given birth by age 13. The sample is comprised of 1501 women. At age 20, 684 women (45.6%) are classified as teen mothers. Of those, 156 (22.8%) had their first child before the age of 17 and are hereafter referred to as “early teen mothers”. We will refer to women who had their first child when they were aged 17 to 19 as “older teen mothers”. We were unable to assign teen mother status to 83 (5.5%) women.

Columns 1 through 3 in Table 1 present characteristics at age 11 to 13 and at age 20 for teen mothers, women who are not teen mothers (non teen mothers) and those we were unable to classify. At age 11 and 13 the future teen mothers have similar years of completed education, enrollment and household size to girls who do not give birth in their teens. Future teen mothers are as likely to co-reside with their father but are slightly less likely to co-reside with their mother. Teen mothers do not appear to be selected from households with lower socioeconomic status.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics - women aged 20 in HSE round 6, 7, 8 or 9 who were observed when they were aged 11 to 13

| Characteristics at age 11–13: | Non teen mothers | Teen mothers | Teen mother indicator missing | Early teen mothers | Other teen mothers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Age | 12.4 | 12.3 * | 12.5 * | 12.4 | 12.3 |

| Years of completed education | 5.53 | 5.58 | 5.39 | 5.46 | 5.61 |

| Enrolment | 0.981 | 0.982 | 0.926 *** | 0.955 | 0.990 *** |

| Toilet | 0.666 | 0.677 | 0.759 * | 0.737 | 0.659 * |

| Assets | 4.24 | 4.15 | 4.83 ** | 4.09 | 4.17 |

| Piped water | 0.501 | 0.465 | 0.494 | 0.481 | 0.460 |

| Resident members | 7.80 | 7.94 | 7.48 | 8.04 | 7.91 |

| Mother co-resident | 0.681 | 0.635 * | 0.602 | 0.673 | 0.623 |

| Father co-resident | 0.262 | 0.260 | 0.313 | 0.327 | 0.241 ** |

| Mother dead | 0.087 | 0.101 | 0.100 | 0.090 | 0.104 |

| Father dead | 0.206 | 0.174 | 0.164 | 0.153 | 0.180 |

| Mother’s vital status missing | 0.027 | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.006 | 0.038 ** |

| Father’s vital status missing | 0.113 | 0.118 | 0.120 | 0.160 | 0.106 * |

| Mother’s education | 5.04 | 4.85 | 6.69 *** | 4.76 | 4.88 |

| Mother’s education missing | 0.136 | 0.139 | 0.145 | 0.115 | 0.146 |

| Resident in ACDSA | 0.907 | 0.902 | 0.880 | 0.917 | 0.898 |

| Characteristics at age 20: | |||||

| Years of completed education | 10.9 | 10.5 *** | 9.9 *** | 10.0 | 10.7 *** |

| Dropped out of school | 0.184 | 0.338 *** | 0.289 | 0.442 | 0.307 *** |

| Mother co-resident | 0.639 | 0.594 * | 0.602 | 0.609 | 0.589 |

| Father co-resident | 0.237 | 0.218 | 0.205 | 0.224 | 0.216 |

| Mother dead | 0.211 | 0.252 * | 0.175 | 0.216 | 0.262 |

| Father dead | 0.435 | 0.401 | 0.385 | 0.403 | 0.400 |

|

| |||||

| Observations | 734 | 684 | 83 | 156 | 528 |

Note: The sample includes all women who were 20 years old in HSE rounds 6, 7, 8 or 9 and who were observed in an earlier HSE round when they were aged 11 to 13 years old. Where women were observed in multiple HSE rounds between the ages of 11 and 13, the most recent observation was used. The notation in column 2 denotes that differences between teen mothers and non teen mothers are significant at 10% (*), 5% (**) and 1%(***) level. Similarly the notation in columns 3 and 5 denote significant differences between those with known teen mother status and those with unassigned status and between early teen and older teen mothers respectively.

The girls that we were unable to classify are significantly less likely to be enrolled in school than girls who are not teen mothers but this is explained by their slightly older agevi. They have marginally higher household socioeconomic status and their mothers have more education.

The final two columns of Table 1 show mean characteristics for early teen mothers and older teen mothers separately. At ages 11 to 13, early teen mothers appear slightly less likely to be enrolled in school and we have more complete information about their parents than older teen mothers.

Although socioeconomic conditions at ages 11 to 13 do not appear to be highly correlated with the probability of becoming a teen mother, we control for these characteristics when we turn to analyze the effects of early childbearing on investments in educationvii. We will do this by using explicit controls for pre-pregnancy characteristics.

(a) Educational attainment and enrolment

We begin to explore the relationship between early childbearing and educational attainment and enrolment in Table 2. The first three columns present results from OLS regressions of years of education at age 20 on indicators that the woman is an older or early teen mother. In order to avoid possible selection issues, all women are included and an indicator that the teen mother variable is missing is added to the regressions.

Table 2.

Educational attainment and teenage childbearing - women aged 20 in HSE round 6, 7, 8 or 9 who were observed in an earlier HSE round when they were aged 11 to 13

| Years of Education at age 20 | Education at age 11/13 | Dropped out of high school at age 20 | Enrolled at age 11/13 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Older teen mother | −0.274*** (0.106) | −0.243** (0.105) | −0.369*** (0.090) | 0.156* (0.089) | 0.206** (0.088) | 0.122*** (0.025) | 0.117*** (0.025) | 0.124*** (0.025) | 0.010 (0.008) | 0.012 (0.008) |

| Early teen mother | −0.953*** (0.163) | −0.859*** (0.161) | −0.853*** (0.138) | −0.083 (0.138) | −0.009 (0.136) | 0.259*** (0.038) | 0.247*** (0.038) | 0.239*** (0.038) | −0.026** (0.013) | −0.017 (0.013) |

| Teen mother indicator missing | −1.080*** (0.216) | −1.197*** (0.212) | −0.965*** (0.182) | −0.292 (0.182) | −0.380** (0.179) | 0.111** (0.050) | 0.135*** (0.050) | 0.120** (0.051) | −0.060*** (0.017) | −0.059*** (0.017) |

| Toilet | 0.322*** (0.123) | 0.281*** (0.106) | 0.068 (0.104) | −0.031 (0.029) | −0.023 (0.029) | 0.002 (0.010) | ||||

| Assets | 0.077*** (0.022) | 0.033* (0.019) | 0.073*** (0.018) | −0.018*** (0.005) | −0.019*** (0.005) | 0.000 (0.002) | ||||

| Piped water | −0.102 (0.120) | −0.177* (0.103) | 0.123 (0.101) | 0.004 (0.028) | 0.006 (0.028) | 0.004 (0.010) | ||||

| Number resident members | −0.006 (0.013) | 0.004 (0.011) | −0.016 (0.011) | 0.007** (0.003) | 0.008** (0.003) | −0.000 (0.001) | ||||

| Mother co-resident | 0.288** (0.129) | 0.034 (0.111) | 0.416*** (0.109) | −0.050 (0.030) | −0.042 (0.030) | 0.019* (0.010) | ||||

| Father co-resident | −0.101 (0.120) | −0.117 (0.103) | 0.026 (0.101) | 0.053* (0.028) | 0.058** (0.028) | 0.001 (0.010) | ||||

| Mother dead | 0.085 (0.206) | 0.143 (0.177) | −0.096 (0.174) | −0.019 (0.048) | −0.015 (0.049) | −0.003 (0.017) | ||||

| Father dead | −0.075 (0.136) | −0.067 | −0.013 | 0.013 | 0.017 | −0.002 | ||||

| Mother’s education | 0.067*** (0.014) | 0.038*** (0.012) | 0.047*** (0.011) | −0.008*** (0.003) | −0.008** (0.003) | 0.001 (0.001) | ||||

| Resident | 0.091 (0.164) | 0.068 (0.141) | 0.038 (0.138) | −0.016 (0.038) | −0.003 (0.039) | 0.021 (0.013) | ||||

| Years of education at 11/13 | 0.611*** (0.027) | |||||||||

| Enrolled at 11/13 | −0.221*** (0.077) | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Observations | 1,501 | 1,501 | 1,501 | 1,501 | 1,501 | 1,501 | 1,501 | 1,486 | 1,486 | 1,486 |

Note: The sample includes all resident women aged 20 in HSE 6, 7, 8 or 9 and who were observed in an earlier HSE round when they were aged 11 to 13. Where women were observed in multiple HSE rounds between the ages of 11 and 13, the most recent observation was used. All regressions include a full set of indicators for the HSE round when the woman was 20 years of age. Regressions in columns 2–5 and 7–10 include a full set of indicators for age at and year of the visit when the woman was between 11 and 13 years old. Regressions in columns 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 and 10 include a full set of indicators for isigodi and indicators that parent’s vital status and mother’s education is missing. Standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

The first column only includes a full set of indicators for the year when the woman was 20 years old. At age 20, older teen mothers have on average 0.27 fewer years of schooling than non-teen mothers of the same age. This educational disadvantage is much larger for early teen mothers. Having a child before the age of 17 is associated with almost 1 full year’s less education at age 20 than a non-teen mother.

In the second column controls for household socio-economic status at age 11 to 13 and a full set of indicators for isigodi (traditional administrative unit) are added. Introducing pre-fertility socioeconomic controls has little effect on the older teen and early teen mother coefficients. The coefficients on the teen mother indicators are slightly reduced but remain significant and substantial. The controls for socio-economic status are significantly related to years of completed education but do not explain much of the teen mother educational disadvantage. The third column adds years of completed education at age 11 to 13. This increases the coefficient of the older teen mother indicator and has no significant impact on the early teen mother coefficient.

If teen childbearing is simply a signal that a woman was a poor student or living in a worse environment for education, we would expect future births to predict the woman lagging behind in school prior to the pregnancy. In columns 4 and 5 of Table 2, we see that girls who are going to be a teen mother do not have significantly less education at ages 11 to 13. In fact, future older teen mothers have 0.16 years more education than girls who will not give birth in their teens, although the coefficient is only significant at the 10% levelviii. The point estimate for early teen mothers is negative, but it is not significant.

Columns 6 to 10 of Table 2 present analogous results for the probability of dropping out of school. The outcome variable is an indicator that the woman had not completed high school and was not enrolled in school at age 20. Similar to the results for attainment, we find that teen mothers are significantly more likely to drop out of high school and that this is not explained by the household characteristics prior to the birth when they were 11 to 13 years of age. Also in line with the results for attainment, we find that early teen mothers are significantly more likely to drop out than women who have a child in their late teen years. Early and late teen mothers are respectively around 25 and 12 percentage points more likely to drop out of high school by age 20 than women who do not give birth in their teens.

The final two columns of Table 2 present results from regressions of enrollment at age 11 to 13 on the teen mother indicators. We find some evidence that women who are going to become early teen mothers are less likely to be enrolled at age 12 or 13. The coefficient is, however, small and no longer significant when pre-fertility household controls are included in the regression.

The 5.5% of our sample for whom we cannot assign teen mother status has completed significantly fewer grades and are more likely to drop out than other girls their age who we know have not given birth in their teens. As a robustness check, we assume that all women with missing teen mother status are not teen mothers and re-run the regressions in Table 2. Doing this attenuates the coefficients for the older teen and early teen mother indicators slightly but they remain substantial and statistically significantix.

In addition to controlling for observed pre-fertility characteristics using OLSx, the dataset is large enough to allow us to control for omitted variables that may jointly determine teen childbearing and educational outcomes by comparing sisters who did and did not give birth in their teens. Although there is the criticism that household characteristics could be different for different sisters at different ages, the advantage is that we can control for any observed and unobserved and unobservable characteristics that are common to the sisters and time invariant. We also only need to observe each woman once (at age 20), which significantly increases our sample size.

Our sample includes all resident women who were aged 20 in any of the HSE rounds 1 to 9. There are 4040 women, 1292 of whom have at least one sister (with the same mother) in the sample. In our sibling fixed effect model, the teen mother coefficient is identified off those sibling groups where there is variation in the teen mother variable. There are 269 sibling groups (made up of 610 women in total) where at least one sister did and at least one sister did not give birth in her teens.

Table 3 presents results from regressions that include sibling fixed effects. For comparison purposes, in the first and third column we present results for this sample without fixed effects. The coefficients on the teen mother indicators are very similar to those for the sample in Table 2. Turning to the fixed effect results, compared to their sisters, women who give birth in their early teens have significantly fewer years of completed schooling at age 20. On average, by age 20, early teen mothers have completed 0.99 years less schooling than their sisters who did not give birth in their teens. Although the point estimate is still negative, older teen mothers are not significantly behind in their educational attainment when compared to their sisters who delay childbearing beyond age 20. Early and older teen mothers are around 35 and 7 percentage points respectively more likely to drop out of high school than their siblings.

Table 3.

Comparison of teenage mothers’ education outcomes with their sibling(s) (mother fixed effects) – women aged 20 in HSE 1 to 9

| Dependent variable:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of completed education at age 20 | Drop out at age 20 | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Older teen mother | −0.437*** (0.070) | −0.198 (0.144) | 0.145*** (0.016) | 0.065* (0.037) |

| Early teen mother | −0.922*** (0.111) | −0.991*** (0.239) | 0.226*** (0.025) | 0.353*** (0.061) |

| Teen mother indicator missing | −0.599*** (0.168) | −1.174*** (0.356) | 0.025 (0.037) | −0.011 (0.091) |

| Individual fixed effects | No | Yes | No | Yes |

|

| ||||

| Observations | 4,040 | 4,040 | 4,040 | 4,040 |

| Number of unique mothers | 3,346 | 3,346 | ||

Note: Sample includes all resident women who were 20 years old in HSE 1 to 9. Regressions include a full set of indicators for year of visit. Standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

(b) Timing of falling behind

Our longitudinal data present the opportunity to investigate more thoroughly the timing of falling behind. We can also document the extent to which women return to school post child birth and whether their schooling recovers in the period after the birth or if they continue to fall behind their peers.

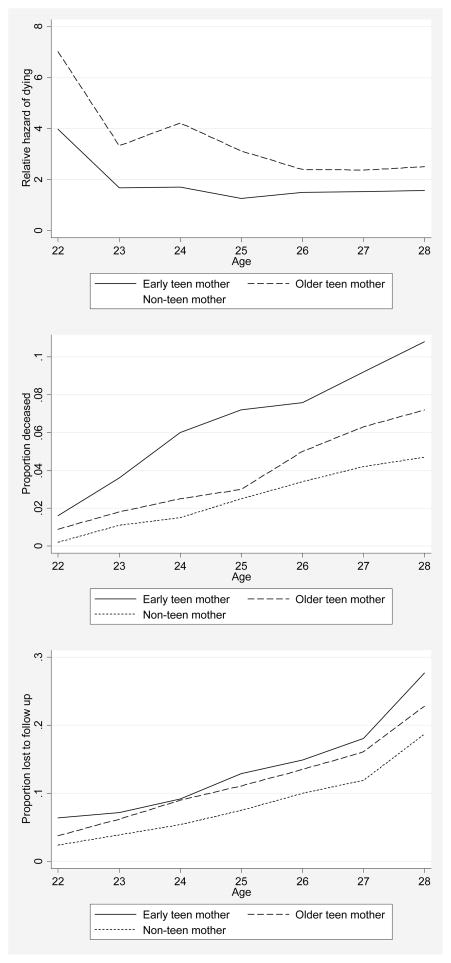

Figure 3 presents enrolment rates and years of completed schooling by age separately for women who have their first birth at 15, 16, 17, 18, and at 23 or older. Following Marteleto et al. (2008) in their study in urban Cape Town, we visually summarize enrolment trajectories before and after birth in the top panel. At ages 12 and 13 enrolment is almost universal and there is no evidence that future teen mothers are less likely to be enrolled than their peers. Enrolment by age follows a similar pattern across all teen mothers with a slight drop in enrolment in the year before the birth and then a substantial drop in the year of the birth.

Figure 3.

Enrollment and years of education by age and age at first birth

It is clear that a significant proportion of teen mothers do not drop out of school although our enrolment measure should not be confused with attendance. The proportion continuing to be enrolled after the birth decreases with age at first birth. Enrolment rates tend to be flat in the year following the birth but upward sloping in the following year. This provides evidence that some teen mothers who had dropped out return to school after the birth. The increase in enrolment one year after the birth tends to be greater for younger teen mothers. By age 20 around 34% of teen mothers are enrolled in school with little difference in enrolment rates by age at first birth. Women who delay their first birth until the age of 20 or later have higher enrolment at every age and are around 10 percentage points more likely to be enrolled than teen mothers at age 20.

The bottom panel in the figure shows the corresponding evolution of completed years of schooling. At age 14, educational attainment does not appear to differ by age at first birth. Teen mothers only begin to fall behind their peers in the year of the birth and a portion of younger teen mothers continue to advance in school post the birth. For women who have their first birth in their late teens, however, the graph flattens out with no apparent increase in the average years of completed schooling between the ages of 18 and 20. At age 20, the educational attainment gap between teen mothers and older mothers decreases with age at first birth. Women who had their first birth at 15 have on average one year less schooling than older mothers. In contrast, women who had their first birth at 18 tend to only be half a year behind older mothers.

Table 4 presents the results of more detailed regressions to investigate the timing of falling behind and the extent to which teen mothers return to school after the birth of their child. The sample includes every HSE observation where the woman was a resident between the ages of 12 and 20. We restrict the sample to women who were at least 20 years old when most recently observed because the final teen mother status of anyone younger was still unknown. The sample includes 27,700 observations on 9,536 individuals, 44% of whom are teen mothers. We have information about enrollment for all the observations and years of education for 27,571 of them. Results in the first column are from OLS regressions of years of completed education on indicators of whether the HSE observation was more than 3 years before the birth, 2 to 3 years before the birth, 1 to 2 years before the birth, 0 to 1 year before the birth, 0 to 1 year after the birth, 1 to 2 years after the birth, 2 to 3 years after the birth and more than 3 years after the birth. Women who have not given birth by the age of 20 are coded as zero on all eight of these timing indicatorsxi. All regressions include a full set of indicators for age and year of observation and the full set of socioeconomic controls from Table 1. Standard errors allow for clustering at the individual level.

Table 4.

Timing of falling behind and dropping out –women between ages of 12 and 20

| Dependent variable: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Years of completed education | Dropped out | |

| (1) | (2) | |

| 3+ years before birth | −0.018 (0.049) | −0.004 (0.004) |

| 2–3 years before birth | 0.019 (0.054) | −0.002 (0.007) |

| 1–2 year before birth | 0.034 (0.052) | 0.015* (0.008) |

| 0–1 years before birth | 0.014 (0.049) | 0.183*** (0.012) |

| 0–1 years after birth | −0.241*** (0.049) | 0.379*** (0.012) |

| 1–2 years after birth | −0.542*** (0.053) | 0.237*** (0.012) |

| 2–3 years after birth | −0.684*** (0.064) | 0.201*** (0.015) |

| 3+ years after birth | −0.905*** (0.083) | 0.288*** (0.017) |

|

| ||

| Observations | 27,571 | 27,700 |

Note: Sample is restricted to women who were at least 20 years of age when most recently observed. Sample includes every observation where the woman was aged between 12 and 20. All regressions include a full set of indicators for age and for year of observation, an indicator that the household has a toilet, count of assets, an indicator that the household has piped water, the number of resident members, an indicator that the mother is co-resident, an indicator that the father is co-residents, an indicator that the mother is deceased, an indicator that the father is deceased, mother’s years of completed education, an indicator that the woman is resident, a full set of indicators for isigodi and indicators that parent’s vital status and mother’s education is missing. Robust standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the individual level.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

For all four periods prior to the birth, teen mothers are not significantly behind in their schooling relative to other women of the same age who will delay child bearing until at least 20 years of age. In the year after the birth, teen mothers are on average 0.24 years behind. The educational attainment gap between teen mothers and other teenagers increases with the time since the birth but at a decreasing rate after two years. This suggests that some of the teen mothers return to school and continue to successfully complete additional years of education. Three years after the birth, teen mothers have, on average, completed close to one year less schooling than their peers.

The second column in Table 4 presents coefficients from a regression of neither having completed high school nor still being enrolled in school on the pre- and post-birth timing indicators. More than two years before the birth, future teen mothers are not significantly less likely to be enrolled in school than other teens of the same age. There appears to be a small but significant pre-pregnancy drop in enrollment for teen mothers in the period between one and two years before the birth. In the year preceding the birth, teen mothers are 18 percentage points less likely to be enrolled in school than their peers indicating that some women leave school during their pregnancyxii. In the year following the birth, teen mothers are 38 percentage points less likely to be enrolled in school than their peers. A sizeable proportion of the teen mothers return to school one to two years after the birth. The gap in non-enrollment between teen mothers and other teens falls to 24 percentage points. It appears that most teen mothers who return to school do so within two years of the birth. The dropout rate does not continue to fall with time.

The 1996 South African Schools Act prohibits schools from expelling pregnant learners and allows these learners to return to school post birth although there is evidence to suggest that this is not always the practice (Panday et al. 2009). In 2007, the Department of Education introduced national guidelines for the prevention and management of learner pregnancy which recommend delaying mothers’ return to school for up to two years after the birth (Department of Education 2007). The evidence in Figure 3 and Table 4 suggests that this recommendation could contribute to higher dropout rates amongst teen mothers. Firstly, Figure 3 clearly shows that young women, including those that have not given birth, begin to drop out of school from age 16 onwards and the likelihood of dropping out increases with age. Second, the results in Table 4 show that the majority of teen mothers who return to school do so within the first two years of the birth.

Our longitudinal data allow us to estimate educational deficits for teen mothers under the assumption that none of them will return to school after the birth. We exclude the 15% of teen mothers whose pre-fertility observation is more than one year before the birth and hold teen mother’s education at pre-birth levels. The estimated educational attainment deficit compared to non teen mothers increases from 0.27 (see Table 2) to 1.15 years for older teen mothers and from 0.953 to 3.00 years for early teen mothers (results available on request). While the assumption that no teen mothers will return is very conservative, delaying mothers’ return to school for two years is likely to exacerbate the educational disadvantage of teen mothers.

(c) Who returns to school

It is evident from Figure 3 and Table 4 that some teen mothers return to school while others dropout permanently. From a policy perspective it is critical to understand the factors that enable young mothers to negotiate parenthood and schooling and those that prevent teen mothers from continuing with their education.

Table 5 examines the determinants of not continuing with school. In order to investigate the pre-fertility correlates of post-birth outcomes, we restrict the sample to teen mothers for whom we have schooling data both pre- and post-birth. Specifically, the sample is comprised of those teen mothers who had an HSE interview within the two years preceding the birth and another HSE interview between one and two years after the birth. We focus on the period one to two years after the birth for our second observation due to enrolment patterns evident in Table 4. Dropout rates for teen mothers were shown to peak in the year following the birth, fall substantially after one year and then remain fairly constant. We exclude from the sample the small percentage of teen mothers who had already matriculated at the HSE interview prior to the birth. The outcome of interest, dropping out, is defined as neither having completed high school nor still being enrolled in school when visited one to two years after the birth. Just over half (51%) the sample were still enrolled and 15% had completed high school at this second observation.

Table 5.

Who completes or returns to school - teenage mothers observed pre and post birth

| Dependent variable: Age standardized dropping out | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Pre-birth HH controls | Post-birth HH controls | |

| (2) | (3) | ||

| Age at first birth | −0.098*** (0.022) | −0.096*** (0.022) | −0.105*** (0.023) |

| Age standardized prior education | −0.351*** (0.032) | −0.319*** (0.033) | −0.321*** (0.033) |

| Pre birth data from 1–2 years prior to birth+ | 0.061 (0.064) | 0.073 (0.064) | 0.079 (0.064) |

| Assets | −0.053*** (0.013) | −0.060*** (0.013) | |

| Toilet | −0.060 (0.079) | −0.029 (0.082) | |

| Piped water | 0.073 (0.074) | 0.190** (0.076) | |

| Resident members | 0.014* (0.009) | 0.019** (0.008) | |

| Mother co-resident | −0.123 (0.082) | −0.100 (0.086) | |

| Father co-resident | 0.177** (0.080) | 0.155* (0.084) | |

| Mother dead | −0.067 (0.102) | −0.009 (0.099) | |

| Father dead | 0.068 (0.073) | 0.062 (0.070) | |

| At least one resident female pensioner | 0.031 (0.071) | −0.015 (0.069) | |

| At least one resident male pensioner | 0.346*** (0.106) | 0.075 (0.103) | |

|

| |||

| Observations | 1,403 | 1,399 | 1,394 |

Note: Prior years of education and dropping out rates are aged-standardized by subtracting the age mean and dividing by the age standard deviation. Sample includes all teenage mothers who had an HSE interview within the two years preceding the birth and another HSE interview between one and two years after the birth. We exclude from the sample the small percentage of teenage mothers who had already matriculated at the HSE interview prior to the birth. All regressions include a full set of indicators for isigodi. Standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1.

0–1 years prior to birth reference category

Given the strong relationship between age and both dropping out of school and pre-birth characteristics, such as educational attainment, it is clearly important to control for age in our regressions. This poses somewhat of a challenge as we are also interested in investigating age at first birth as one of the key determinants of who returns to school. The construction of our sample is such that age and age at first birth are necessarily collinear. Our solution is to employ age standardized versions of dropping out and pre-birth educational attainment. In this way we can control for the confounding effect of age and also investigate the effect of age at first birth on subsequent outcomes. Age standardization is relative to the full sample of resident women at every HSE.

The first column of Table 5 presents results from a regression of an age standardized indicator of dropping out on age at first birth, age standardized pre-birth education and an indicator that the pre-birth data are from 1 to 2 rather than 0 to 1 years prior to the birth. Not surprisingly given the results in Table 2, age at first birth of teen mothers is significantly positively associated with better schooling outcomes. The younger a teen mother at the birth of her first child, the less likely she is to complete high school or continue to be enrolled. Similar to Marteleto et al. (2006) in Cape Town, we find that teen mothers who were further ahead for their age prior to the birth are significantly more likely to return and complete their schooling.

The second column in Table 5 includes a range of pre-birth household controls. The third column includes the same set of household controls but measured at the post-birth observation. Including either pre- or post-birth household controls has no effect on the association between age at first birth and pre-birth educational attainment and the probability of dropping out of school. Household assets pre- and post- birth appear to be protective of schooling for teen mothers. Interestingly, pre-birth and current co-residence with a father are associated with a higher probability of dropping out, although coefficients are only significant at the 10% level for current co-residence. Co-residence with a male pensioner pre-birth is also associated with a higher probability of dropping out.

4. MORTALITY AND EARLY CHILDBEARING

We have documented a clear association between early childbearing and poor educational outcomes. We now turn to investigate another dimension of human capital, namely health. Perhaps an even greater concern related to early childbearing than schooling disruptions is the consequences of adolescent unprotected sex in a high HIV prevalence area and the additional risks that pregnancy means for HIV infection.

Documenting the extent to which teen mothers are at greater risk for morbidity and mortality is clearly important in its own right. In addition such an analysis may generate insights into attrition-related biases in the association between teen childbearing and educational outcomes.

In the ACDSA, HIV prevalence is substantially higher than national rates with 23% of women aged 15 to 24 estimated to be HIV positive (Welz et al. 2007). The HIV incidence rate per 100 person years was 3.9 and 5.6 for women aged 15 to 19 and 20 to 24 respectively (Barnigshausen et al. 2008). Similar to the national picture, HIV prevalence in the ACDSA peaks five years earlier for women than men (Barnigshausen et al. 2008).

To analyze mortality we restrict our sample to all resident women who were aged 20 in any of HSE rounds 1 to 9 and we follow these women until 31 December 2012. We use Cox proportional hazard models as survival analysis techniques allow us to appropriately account for censoring due to women leaving the study area. Our estimates of the relative risk of dying shown in Table 6 suggest a strong association between early childbearing and mortality. The estimated relative hazard rate for teen mothers is 1.4xiii. In other words, teen mothers face a hazard of dying that is 40% greater than the hazard for women who delayed childbearing till at least age 20.

Table 6.

Mortality and early childbearing among women aged 20 in any of HSE 1 to 9

| All Causes | AIDS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Teen mother | 1.410** (0.193) | ||||

| Older teen mother | 1.297* (0.193) | 1.310* (0.199) | 1.869** (0.496) | ||

| Early teen mother | 1.812*** (0.365) | 1.843*** (0.380) | 3.326*** (1.071) | ||

| Teen mother status missing | 2.886*** (0.744) | 2.886*** (0.744) | 2.746*** (0.722) | 4.522*** (1.809) | |

| Toilet | 1.221 (0.225) | 1.359 (0.358) | 1.621* (0.469) | ||

| Assets | 1.024 (0.032) | 1.049 (0.045) | 0.953 (0.051) | ||

| Piped water | 1.435** (0.254) | 1.346 (0.338) | 1.355 (0.385) | ||

| Resident members | 0.973 (0.018) | 0.968 (0.025) | 0.975 (0.030) | ||

| Electricity | 0.824 (0.158) | 0.759 (0.201) | 0.953 (0.294) | ||

| Years of education | 0.944** (0.025) | 0.945 (0.038) | 0.925* (0.037) | ||

| Isigodi | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

| |||||

| Observations | 5,219 | 5,219 | 5,051 | 2,231 | 3,621 |

Note: Hazard rates for mortality from Cox proportional hazard model. The sample in columns 1 to 4 includes all resident women who were aged 20 in any of HSE 1 to 9. The sample in column 4 is further restricted to teen mothers. The sample in column 5 includes all resident women who were aged 20 in any of HSE 1 to 6. Women are followed from the HSE visit date when they were 20 years old until 31 December 2012 for columns 1 to 4 and until 31 December 2009 for column 5. All regressions include a full set of indicators for the year in which the woman was 20 years old. All socio-economic variables are from the HSE visit when the woman was 20 years old. Standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

The hazard of dying for women whose teen mother status is unknown is 2.9 times that of non teen mothers. This is not surprising as early death would reduce the probability of these women ever completing a pregnancy or general health interview. As a robustness check of our teen mother coefficient, we re-ran the regression assuming that all unclassified women were not teen mothers. While the coefficient teen is attenuated, it remains significant and substantial (relative hazard rate = 1.27 standard error 0.166).

In column 2 we include separate indicators for older and early teen mothers. Within the teenage years, fertility timing appears to matter. Women who had a first birth before the age of 17 have significantly higher mortality risk than older teen mothers. Compared to women who delayed child bearing until at least age 20, older teen mothers and early teen mothers face hazards of dying at are 30% and 80% greater respectively. The regression in column 3 includes controls for socio-economic status at age 20. Interestingly, the inclusion of these variables has little effect on the teen mother coefficients and of all the household SES indicators, only access to piped water is a significant predictor of death. Years of completed education at age 20 is significantly associated with the probability of dying. Relative to other women of the same socioeconomic status, every additional year of education is associated with a 6% decrease in the hazard of dying. The sample in column 4 is restricted to teen mothers. Among teen mothers, there does not appear to be any association between educational attainment or household SES at age 20, and the risk of dying.

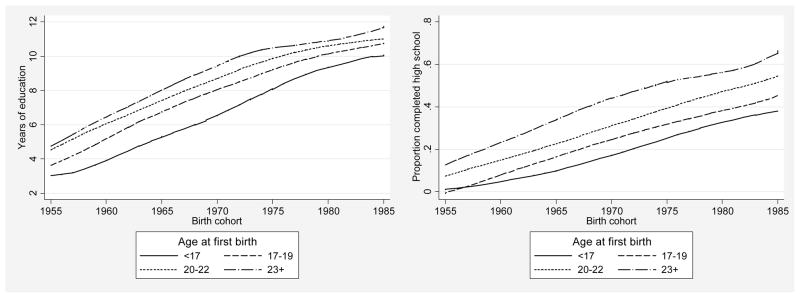

Given the distribution of age at first birth shown in Figure 1, the majority of the women who did not give birth in their teens are likely to have a child in their early twenties. It is possible that the hazard rates for teen mothers and older mothers would converge if we observed the women over a longer period. We can take advantage of the length of the panel to investigate relative probabilities of survival over periods of differing length. We restrict the sample to women who turned 20 years old between 1 January 2000, when surveillance began, and 31 December 2004. We then estimate relative hazard rates of dying by each age from 22 to 28.

The top panel of Figure 4 presents the relative hazard rates of dying for early teen mothers and older teen mothers at each age from 22 to 28 years old. The middle panel shows the proportion of women who have died at each age and the bottom panel, the proportion lost to follow up at each age. At every age, teen mothers are both more likely to be deceased and to be lost to follow up than non-teen mothers, with mortality and attrition rates highest for early teen mothers. By age 22, a very small percentage of the sample has died but, as we can see in the top panel, early teen mothers and older teen mothers are 7 and 4 times more likely to have died than other women. The relative hazard rate falls steeply between age 22 and 23 and then continues to decline but at a much slower rate. If we follow our sample of women through till age 28, the relative hazard rate for early teen mothers and older teen mothers is 2.5 and 1.6 respectively. Over periods ranging from two to eight years, early childbearing is consistently associated with significantly higher mortality.

Figure 4. Relative hazard rates, mortality and attrition over time.

Notes to Figure 4: Sample is all women who turn 20 year of age between 1 January 2000, when surveillance began, and 31 December 2004.

The bottom panel of Figure 4 shows that a non-trivial percentage of the women are lost to follow up, with attrition rates higher amongst teen mothers. In most cases attrition occurs because the respondent was no longer resident and was not considered a non-resident member of a household still residing in the ACDSA. We investigate the correlates of attrition by following the women who were aged 20 in HSE 1, 2 or 3 over a period of seven years. Appendix Table A3 presents results from multinomial logistic regressions where the outcome seven years after the HSE visit is either “deceased” or “lost to follow up”, with “alive” serving as the reference category. Teen mothers are both significantly more likely to be deceased and lost to follow up than non-teen mothers. In the second column, we include a range of controls for household socioeconomic status at age 20. While teen mothers are still significantly more likely to be deceased, they are no longer more likely to be lost to follow up. Household size, access to piped water and years of completed education are negatively related to the probability of being lost to follow up.

Appendix Table 3.

Attrition and mortality seven years after the HSE visit date for women aged 20 in HSE 1, 2 or 3

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: | ||||||

| Lost to follow up | Deceased | Lost to follow up | Deceased | Lost to follow up | Deceased | |

| Older teen mother | 0.029 (0.150) | 0.401* (0.220) | 0.064 (0.159) | 0.437* (0.228) | ||

| Early teen mother | 0.372* (0.213) | 0.952*** (0.279) | 0.280 (0.230) | 1.001*** (0.292) | ||

| Teen mother indicator missing | 2.178*** (0.225) | 1.911*** (0.334) | 2.223*** (0.244) | 1.950*** (0.347) | ||

| Toilet | 0.012 (0.188) | 0.183 (0.256) | −0.068 (0.292) | 0.292 (0.374) | ||

| Assets | 0.027 (0.033) | 0.012 (0.045) | 0.057 (0.053) | 0.059 (0.063) | ||

| Piped water | −0.433** (0.182) | 0.299 (0.249) | −0.398 (0.279) | 0.383 (0.361) | ||

| Number of resident members | −0.083*** (0.020) | −0.046* (0.027) | −0.134*** (0.035) | −0.082** (0.040) | ||

| Electricity | 0.032 (0.206) | −0.163 (0.274) | −0.228 (0.311) | −0.376 (0.392) | ||

| Years of education | −0.114*** (0.028) | −0.050 (0.041) | −0.136*** (0.045) | −0.054 (0.062) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Observations | 1,898 | 1,861 | 797 | |||

Note: Coefficients from multinomial logistic regression with the base category being women who are alive and still followed by ACDIS. The sample includes all resident women who were aged 20 in any of HSE 1 to 3. In column 3 the sample is further restricted to teen mothers. All regressions include a full set of indicators for the year in which the woman was 20 years old. Regressions in columns 2 and 3 include a full set of indicators for isigodi. Standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

The sample is restricted to teen mothers in the third column of Table A3. The same variables that predicted loss to follow up in the full sample are predictive of being lost to follow up for teen mothers. On these observable characteristics, teen mothers who are lost to follow up do not appear to be a select group. Among teen mothers years of education at age 20 is negatively associated with being lost to follow up. This suggests that earlier results examining the educational deficit for teen mothers may be biased downward (in absolute terms) due to attrition.

As a robustness check, we re-estimated the relative hazard rates shown in column 1 of Table 6 assuming that all teen mothers who were lost to follow up, were still alive on 31 December 2012. The coefficient on early teen mothers is reduced but still substantial and highly significant (relative hazard rate=1.27 standard error=0.166).

While we are careful not to attribute causality, there is a significant association between teenage childbearing and mortality before the age of 30 that is not explained by socioeconomic status in early adulthood. The literature suggests that a combination of biological and sociological factors place teen mothers at particularly high risk of HIV acquisition. While we do not have data on HIV incidence, we can use data on cause of death and sexual behavior to explore the mechanisms that put these young women at risk.

Within a year of each death in the ACDSA, nurses conduct a verbal autopsy with family and caregivers of the deceased to determine the cause of death. A verbal autopsy is an instrument used in areas with no vital registration system in order to diagnose probable cause of death. At least two physicians review the verbal autopsy interviews and independently assign a cause of death. Verbal autopsy data have been validated using medical records from the local hospitals. The data show very high sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value in the case of both AIDS and non-AIDS causes of deaths (Hosegood, Vanneste and Timaeus 2004)xiv. Amongst the women depicted in Figure 4 who had died by age 28, AIDS is indicated as the underlying cause of death for 69%. AIDS related deaths are particularly prevalent among teen mothers, especially early teen mothers. Just over half (53%) of non-teen mother deaths are AIDS related in contrast to 78% of older mother deaths and 86% of early teen mother deaths.

In the final column of Table 6, we restrict our focus to AIDS deaths only. We follow women until 31 December 2009 as verbal autopsy data are not yet available for deaths beyond 2009. Controlling for household SES at age 20, the hazard of an AIDS related death for older teen mothers and early teen mothers are 1.9 and 3.3 times that for non-teen mothers respectively. Higher mortality risk among teen mothers is clearly driven by increased risk of AIDS related mortality.

Ideally we would like to be able to separate the harmful effects of unprotected sex (as distinct from just being sexually active) from childbearing or pregnancy episodes. Unfortunately, we are not able to investigate the relationship between age at sexual debut and subsequent mortality in our dataxv. Our sexual activity data do, however, suggest that teen mothers engage in riskier sexual behavior and this is not explained by earlier sexual debut.

Among eligible women aged 15 to 19 years of age, 78% completed at least one women’s general health survey between 2005 and 2012. We focus on all 15 to 19 year olds who are sexually active at the time of the women’s general health survey. Where women were interviewed multiple times, we select the first observation where they reported being sexually active. Table 7 shows that among 15 to 19 year olds who are sexually active, teen mothers are around 16 percentage points less likely to report using a condom at last sex than non teen mothers. Earlier sexual debut is also associated with lower condom use at last sex but controlling for age of sexual debut has no impact on the teen mother coefficient. Consistent with Jewkes et al. (2009), we find that teen mothers have significantly older sexual partners than non teen mothers. Controlling for age at sexual debut, the sexual partners of teen mothers are on average half year older than those of non teen mothers.

Table 7.

Condom use and age of sexual partner – women aged 15 to 19 between 2005 and 2012

| Dependent variable: | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Used condom at last sex | Ever used condom with last sexual partner | Always used condom with last sexual partner | Partner age difference | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Teen mother | −0.162*** (0.018) | −0.157*** (0.018) | −0.094*** (0.018) | −0.095*** (0.018) | −0.220*** (0.016) | −0.216*** (0.017) | 0.584*** (0.117) | 0.499*** (0.120) |

| Age of sexual debut | 0.009 (0.008) | −0.002 (0.008) | 0.008 (0.008) | −0.169*** (0.057) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Observations | 3,088 | 3,088 | 3,106 | 3,106 | 3,106 | 3,106 | 2,869 | 2,869 |

Note: The sample includes all 15 to 19 year olds who were sexually active at the time of the women’s general health survey conducted annually between 2005 and 2012. Where women were interviewed multiple times, the first observation where they reported being sexually active was used. Among eligible women aged 15 to 19 between 2005 and 2012, 76% completed at least one women’s general health survey. All regressions include a full set of indicators for age and a full set of indicators for the year of the women’s general health survey. Standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

5. CONCLUSION

We examine the relationship between teen fertility and both subsequent educational outcomes and mortality risk in rural South Africa. We use a rich longitudinal dataset from the Africa Centre Demographic Information System that allows us to control for multiple characteristics of the teen mothers and their households at an early age before childbearing. We find that teenage fertility is associated with disadvantages in education levels and with higher risk of mortality at a young age.

In a setting where two-thirds of women have given birth by the age of 21, our evidence shows that fertility timing matters. Teen mothers have significantly worse educational outcomes than women who delay their first birth till at least age 20 and these effects are more pronounced for the youngest teen mothers. Although a portion of women remain enrolled in school at age 20, the vast majority (90%) has either dropped out or completed high school by then. Delaying birth until that point is evidently less disruptive of the woman’s education. Our findings on educational outcomes do not seem attributable to adverse pre-fertility characteristics and are robust to multiple methodologies of estimation. We use OLS models, propensity score matching and sibling fixed effects and find consistent results.

Our longitudinal data allow us to investigate the timing of falling behind. We do not see any evidence of declines in enrolment prior to the birth nor are future teen mothers behind in their schooling relative to their peers. A large proportion of the educational deficit is accrued, as might be expected, around the time of the birth. Teenage mothers do, however, continue to accumulate additional educational deficits with time. Within two years of giving birth, teen mothers are behind by two thirds of a year. This deficit grows to 0.79 within three years of the birth. Similarly, comparative dropout rates are particularly high during the year of giving birth and while they decrease within two years of the birth, they remain high relative to girls of the same age who have not yet given birth.

We find a significant association between teenage childbearing and mortality before the age of 30 that cannot be explained by socioeconomic status in early adulthood. The majority of deaths are caused by AIDS with a higher percentage of teen mother deaths being AIDS-related. Similar to our findings for education, younger teen mothers face the highest morality risk. Among sexually active adolescents, we find teen mothers to engage in riskier sexual behaviors. Teen childbearing is associated with lower condom use and greater partner age gaps. If pregnancy increases the probability of contracting and transmitting HIV due to biological changes, it would be important to provide pregnant women - and ideally their partners - with this information along with protection advice. This recommendation is valid for women of any age. Teenage pregnancies, however, create an even greater challenge given that adolescent girls tend to initiate antenatal care later than older pregnant women (Ryan et al. 2009, Zabin and Kiragu 1998)xvi.

Appendix Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics of those women not seen between age 11 and 13 and those included in Table 1

| Included in Table 1 | Not observed at age 11 to 13 | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Years of education | 10.7 | 10.4 *** |

| Dropout | 0.260 | 0.334 *** |

| Older teen mother | 0.352 | 0.333 |

| Early teen mother | 0.104 | 0.116 |

| Teen mother indicator missing | 0.055 | 0.070 |

| Toilet | 0.816 | 0.868 *** |

| Assets | 6.19 | 6.56 *** |

| Piped water | 0.650 | 0.736 *** |

| Number of resident members | 8.06 | 7.62 ** |

| Mother co-resident | 0.616 | 0.387 *** |

| Father co-resident | 0.227 | 0.106 *** |

| Mother dead | 0.227 | 0.291 *** |

| Father dead | 0.417 | 0.444 |

| Mother’s education | 5.03 | 5.43 |

|

| ||

| Observations | 1501 | 497 |

Note: The sample includes 20 year old women in HSE 6, 7, 8 or 9. The notation in column 2 denotes that differences between women not seen at age 11 to 13 and women included in Table 1 are significant at 10% (*), 5% (**) and 1%(***) level.

Appendix Table 2.

Comparison of teen mother estimates for women included and excluded from the sample in Table 1

| Years of completed education at age 20 | Drop out at age 20 | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| In sample | 0.255* (0.134) | −0.024 (0.031) |

| Older teen mother | −0.460** (0.190) | 0.246*** (0.043) |

| In sample x older teen mother | 0.205 (0.217) | −0.127** (0.049) |

| Early teen mother | −0.815*** (0.278) | 0.310*** (0.063) |

| In sample x early teen mother | −0.121 (0.324) | −0.054 (0.074) |

| Teen mother indicator missing | −0.903*** (0.192) | 0.088** (0.044) |

|

| ||

| Observations | 1,998 | 1,998 |

Note: The sample includes 20 year old resident women in HSE 6, 7, 8 or 9. All regressions include a full set of indicators for the HSE round in which the woman was 20 years old.

Footnotes

Ardington acknowledges funding from the Hewlett/PRB Global Teams of Research Excellence in Population, Reproductive Health and Economic Development and National Institutes of Health Fogarty Internal Centre under grant R01 TW008661-01. Menendez acknowledges funding from the Population Research Center, Grant R24 HD051152-05 from the NICHD and the Center for Human Potential and Public Policy at The University of Chicago. Mutevedzi acknowledges funding from the Wellcome Trust, Grant 082384/Z/07/Z. Analysis is based on data collected through the Africa Centre Demographic Information Systems supported by Wellcome Trust Grants 065377/Z01/Z and 082384/Z07/Z. We thank Nicola Branson, Elodie Djemaï-Kargougou and Marie-Louise Newell for their helpful comments on the paper.

The child support grant is a means tested transfer to primary caregivers of children under 15. The amount was R260 per month during 2011 (35 dollars at the 2011 mean market exchange rate).

Evidence from the Cape Area Panel Study (Ranchhod et al. 2011) relies, in part, on retrospective data collected in the first wave and sample sizes do not permit an investigation into fertility timing within the teen years.

This paper’s findings are strictly representative for women in the study area (described in more detail in the following section), but the setting is similar to many parts of South Africa. The field site is located in the most populous province of KwaZulu-Natal. The area is mostly rural but includes a township and peri-urban areas. While the area is relatively poor, there is considerable variation in both household socio-economic status and individual educational attainment within the field site.

Using a series of national datasets, Branson et al. (2012) estimate that around a quarter of South African women aged 20 had their first birth before their twentieth birthday. Our estimates of teen childbearing among African 20 year olds from the 2001 Census for all rural areas and for the whole KwaZulu-Natal are around 35%.

See Appendix Table A1 for a comparison of the characteristics of those 20 year olds for whom we do not have a pre-fertility observation and those in our sample. Women who we do not observe between 11 and 13 years of age are as likely to be older teen mothers, early teen mothers or have unclassified teen mother status as women in the sample. These women are substantially and significantly less likely to co-reside with either parent. They have significantly higher socioeconomic status and live in smaller households although these differences are not substantial. They have significantly less education and are significantly more likely to have dropped out of school.

In the regression of enrolment on an indicator that the girl’s status is unknown, the indicator is no longer statistically significant when we include age.

We do not include father’s education due to the high proportion of missing data on this variable.

Using data from the Cape Area Panel Study, Lam, Marteleto and Ranchhod (2009) find that young people who progress through school ahead of their cohorts have earlier sexual debut and greater age differences with their sexual partners. A consequence of high rates of grade repetition is that these girls interact with classmates who may be several years older. They find that exposure to older classmates explains a significant fraction of the earlier sexual debut.

Appendix Table 2 presents coefficients from regressions that include all 20 year old resident women in HSE 6, 7, 8 or 9 regardless of whether they were observed at ages 11 to 13. The teen mother indicators are interacted with an indicator that the woman is in the sample included in Table 2. The only significant interaction effect is for the probability of drop out among older teen mothers with the result that older teen mothers who are excluded from the sample are even more likely to have dropped out of school by age 20 than those included in the sample.

We find very similar results using a propensity score reweighting approach. Results are available from the authors upon request.

These variables are in essence an interaction of a teen mother indicator with indicators for a time trend relative to the date of a woman’s first birth. The teen mother indicator, and therefore the interaction terms, equal zero for women whose first birth was later than age 19.

We re-ran the regressions in Table 4 with the timing indicators being relative to 40 weeks before the birth of the child. In these models, women were only 1.4 percentage points more likely to not be in school in the year preceding the start of the pregnancy (results available on request).

The equality of the survivor functions of teen mothers and other women is also rejected by the non-parametric log-rank test (Chi2(1)=7.63 p-value=0.0057)

The sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value of the verbal autopsies were over 90% for non-AIDS deaths. Sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value were 80, 82 and 85%, respectively, for AIDS deaths.