Abstract

Objective

Gouty arthritis is caused by precipitation in joints of crystals of monosodium urate (MSU). While it has been reported that mast cells (MCs) infiltrate gouty tophi, little is known about the actual roles of MCs during acute attacks of gout. This study was undertaken to assess the role of MCs in a mouse model of MSU crystal-induced acute arthritis.

Methods

We assessed the effects of intra-articular (i.a) injection of MSU crystals in various strains of mice with constitutive or inducible MC deficiency, or in mice lacking IL-1β or other elements of innate immunity. We also assessed response to i.a. injection of MSU crystals in genetically MC-deficient mice after i.a. engraftment of wild-type or IL-1β−/− bone marrow-derived cultured MCs.

Results

We show that MCs can augment acute tissue swelling following i.a. injection of MSU crystals in mice. We report further that IL-1β production by MCs contributes importantly to MSU crystal-induced tissue swelling, particularly during its early stages, and that selective depletion of synovial MCs can diminish MSU crystal-induced acute inflammation in the joints.

Conclusion

Our findings identify a previously unrecognized role for MCs and MC–derived IL-1β in contributing to the early stages of MSU crystal-induced acute arthritis in mice.

INTRODUCTION

Acute attacks of gout are initiated by the precipitation of crystals of monosodium urate (MSU) in joints. Gout’s prevalence has increased recently, with approximately 6.1 million people with a history of gout in the US alone (1). While several lines of evidence support the importance of IL-1β (2, 3) in gout, less is known about the extent to which different populations of innate immune cells contribute to IL-1β production in this disorder.

Mast cells (MCs) are sentinels of innate immunity that occur in virtually all vascularized tissues (4). Traditionally regarded primarily as effector cells in IgE-dependent acquired immune responses, MCs are now emerging as key players, together with dendritic cells and monocytes, in first defense against invading pathogens and in interactions with environmental stimuli and external toxins (4). Upon activation, MCs can secrete a large spectrum of mediators including stored products such as histamine and tryptase as well as many cytokines, including IL-1β (5).

Because many patients with gout respond clinically to treatment with inhibitors of IL-1 (6), and MCs represent a source of IL-1 in a mouse model of antibody-mediated arthritis (5), we hypothesized that MCs can contribute to early stages of acute arthritis in response to uric acid crystals through production of IL-1β. We now report evidence that strongly supports that hypothesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6J mice, WBB6F1-KitW/W-v (KitW/W-v) mice [and the corresponding control WBB6F1-Kit+/+ (Kit+/+) mice], IL-1R1−/− (B6.129S7-Il1r1tm1Imx/J), IL-18−/− (B6.129P2-Il18tm1Aki/J) and iDTRfl/fl mice (C57BL/6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(HBEGF)Awai/J) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Me). C57BL/6J (WT) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and either bred at the Stanford University Research Animal Facility or used for experiments after maintaining the mice for at least two weeks in our animal facility. C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh mice were originally provided by Peter Besmer (Molecular Biology Program, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA); we then backcrossed these mice to C57BL/6J mice for more than 11 generations (7). Mcpt8DTR/+ (and the corresponding control Mcpt8+/+) mice (8), IL-1α−/− (9), IL-1β−/− (9), TNF−/− (10) and Cpa3-Cre; Mcl-1fl/fl mice (and the corresponding control Cpa3-Cre; Mcl-1+/+ mice) (11) were all on the C57BL/6 background and bred and maintained at the Stanford University Research Animal Facility. We used age-matched male mice for all experiments. All animal care and experimentation were conducted in compliance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and with the specific approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Stanford University.

Human samples

We studied human samples under protocols that were approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board (IRB) and included subjects’ informed consent. Synovial fluids were obtained by needle aspiration of actively inflamed large or medium joints by a board certified rheumatologist at the Veteran’s Administration Hospital (Palo Alto, CA). Grossly bloody fluid was excluded from analysis. Synovial fluid was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min and supernatants removed and frozen at −80° C until use in experiments as described below. The diagnosis of gout was confirmed by identification of negatively birefringent intracellular needle shaped crystals on microscopic examination of synovial fluid under polarizing microscopy. The diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis was made as defined by the 1987 revised criteria for rheumatoid arthritis (12).

Histamine levels were measured by competitive ELISA (Beckman coulter). IL-1β levels were measured using a high sensitivity ELISA (eBioscience; lower detection limit 0.16 pg/ml). Total tryptase levels were measured using an immunoCAP assay (CAP; Phadia Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden). Mature tryptase levels were measured by ELISA as described elsewhere (13). Both total and mature tryptase assays were performed in parallel at Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, VA, USA), by individuals not aware of the identity of individual specimens.

Preparation and intra-articular injection of MSU crystals

MSU crystals were prepared as described previously (2). 1 g of uric acid (Sigma) in 180 ml 0.01 M NaOH was heated to 70° C. NaOH was added as required to maintain pH between 7.1 and 7.2 and the solution was filtered and incubated at RT with slow and continuous stirring for 24 h. MSU crystals were kept sterile, washed with ethanol, dried, autoclaved and re-suspended in PBS by sonication. MSU crystals contained < 0.005 EU/mL endotoxin (LAL endotoxin assay, GenScript).

In most experiments (and unless stated otherwise), we injected 0.5 mg MSU i.a. in 10 μl PBS in one ankle and PBS only in the contra-lateral ankle. We used Microliter Syringes #705 (Hamilton) with 27G needles for all i.a. injections. Injections were performed under isoflurane anesthesia, and the quality of i.a. injection was controlled by assessing location of MSU crystals deposition by histology on ankle tissue collected 24 h after the injection. In some experiments, we used MC-deficient mice engrafted with WT BMCMCs in one ankle and IL-1β−/− BMCMCs in the contra-lateral ankle and injected these mice with MSU crystals in both ankles (Figure 3, A and B). We also injected DT-treated Cpa3-Cre; iDTR mice with MSU crystals in both ankles (Figure 4, F and G). Ankle swelling was measured at different time points using a precision caliper (Fisherbrand Traceable Digital Calipers; Fischer Scientific).

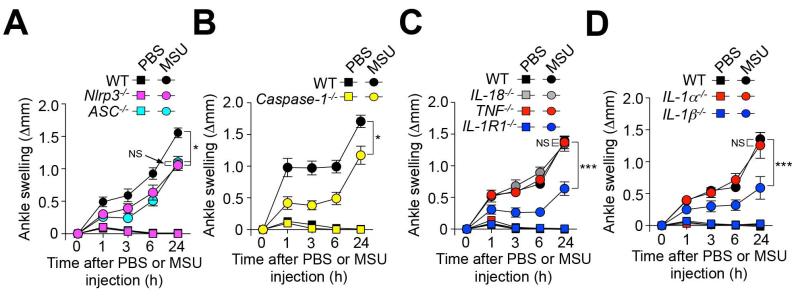

Figure 3. Contributions of the NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-1R1, and IL-1β to MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling.

Changes in ankle thickness in (A) C57BL/6J (WT) (n=11), Nlrp3−/− (n=9) and ASC−/− (n=10) mice; (B) C57BL/6J (WT) (n=14) and Caspase-1−/− (n=11) mice; (C) C57BL/6J (WT) (n=16), TNF−/− (n=12), IL-18−/− (n=10) and IL-1R1−/− (n=13) mice; and (D) C57BL/6J (WT) (n=9), IL-1α−/− (n=7) and IL-1β−/− (n=10) after i.a. injection of 0.5 mg MSU or PBS. Data are shown as means ± SEM. * or *** = P < 0.05 or 0.001 vs. indicated groups by ANOVA. Differences in swelling between MSU crystal-injected vs. the corresponding PBS-injected ankles are significant at each time point (P < 0.05 by unpaired Student’s t-test) for all groups of mice. NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

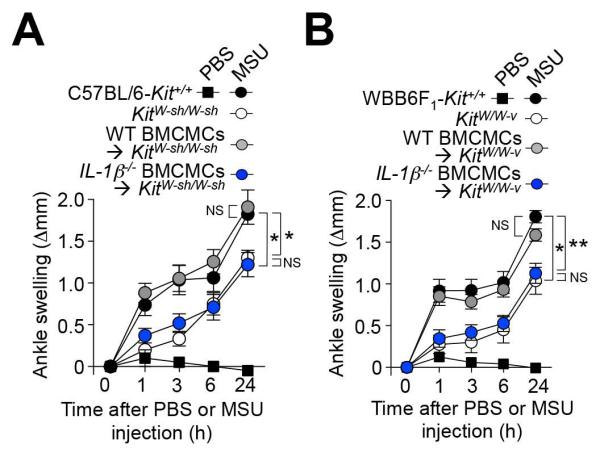

Figure 4. Contributions of MC-derived IL-1β to MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling.

Changes in ankle thickness after i.a injection of 0.5 mg MSU or PBS in (A) C57BL/6-Kit+/+ (n=8) or MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice (n=6), and KitW-sh/W-sh mice engrafted i.a. with C57BL/6J (WT) (n=11) or C57BL6-IL-1β−/− (n=10) BMCMCs; and (B) WBB6F1-Kit+/+ (n=17) or MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/W-v mice (n=8), and WBB6F1-KitW/W-v mice engrafted i.a. with C57BL/6J (WT) (n=15) or C57BL/6-IL-1β−/− (n=11) BMCMCs. Data are shown as means ± SEM from three independent experiments (except for MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice, which were included in two of the three independent experiments). * or ** = P < 0.05 or 0.01 vs. indicated groups by ANOVA. NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

Culture and adoptive transfer of MCs

Bone marrow-derived cultured MCs (BMCMCs) were obtained by culturing bone marrow cells from C57BL/6J WT or C57BL/6-IL-1β−/− mice in 20% WEHI-3 conditioned medium (containing IL-3) for 6 weeks, at which time cells were >98% c-KIT+ FcεRIα+. BMCMCs were transferred by intra-articular injection (2 injections of 106 cells in 10 μl PBS/each injection). Experiments were performed 6 weeks after transfer of BMCMCs.

Diphtheria toxin-mediated ablation of MCs or basophils

For MC ablation, Cpa3-Cre+; iDTRfl/+ and Cpa3-Cre−; iDTRfl/+ littermates received two i.a injections (one week apart) of 50 ng diphtheria toxin (DT) in 20 μl PBS in one ankle and injections at the same time of PBS only in the contra-lateral ankle. Mice were injected with MSU crystals in both ankles one week after the last DT injection. In preliminary experiments, we also assessed whether MCs were depleted two days after a single i.p. injection of 500 ng DT. For basophil depletion, Mcpt8DTR/+ and Mcpt8+/+ littermates received a single i.p. injection of 500 ng DT two days before i.a. injection with MSU crystals.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

We used flow cytometry to identify and enumerate blood basophils (CD49b+; IgE+), eosinophils (Siglec-F+; SSChigh), monocytes (Siglec-F−; CD11b+; Gr-1low) and neutrophils (Siglec-F−; CD11b+; Gr-1high), as well as peritoneal MCs (c-KIT+; IgE+). Briefly, blood cells were lysed by treatment with ACK buffer 2 times for 5 min. Cells were blocked with unconjugated anti–CD16/CD32 antibodies on ice for 5 min and then stained with a combination of the following antibodies on ice for 30 min: for blood leukocytes analysis, Siglec-F-PE (E50-2440; BD Biosciences), CD11b-eFluor450 (M1/70; eBioscience), CD49b-APC (DX5; eBioscience), IgE-biotin (23G3; eBioscience), and Gr-1-FITC (RB6-8C5; eBioscience). For peritoneal MCs, c-KIT-APC (ACK2; eBioscience), IgE-biotin (23G3; eBioscience). Cells were then incubated for 15 min with PE-Texas Red Streptavidin (BD Pharmingen). Data were acquired on LSRII and Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) flow cytometers and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Histologic analysis

Joints were fixed in 10% formalin, decalcified for 10 days in EDTA 0.5M pH=8, embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were stained with 0.1% Toluidine blue (for histologic examination of MCs) or H&E (for histologic examination of leukocytes). Images were captured with an Olympus BX60 microscope using a Retiga-2000R QImaging camera run by Image-Pro Plus Version 6.3 software (Media Cybernetics).

Statistical analyses

A non-parametric Mann-Whitney test (two-tailed) was used for statistical analysis of tryptase, histamine and IL-1β levels in human synovial fluids. Differences between groups were assessed for statistical significance by ANOVA (for ankle swelling) or using an unpaired Student t test (when only two sets of data were compared). P values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant. Unless otherwise specified, all data are presented as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

MCs contribute to MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling in mice

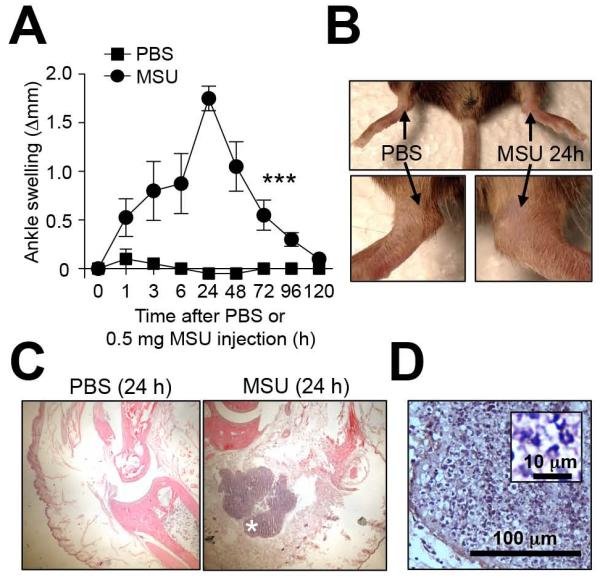

To investigate the importance of MCs in acute gouty arthritis, we developed a mouse model consisting of performing intra-articular (i.a.) injections of MSU crystals into the ankle joints of mice (Figure 1, A-C). Injection of MSU crystals induced ankle swelling that was maximal at 24 h (Figure 1, A and B), a time at which acute inflammatory infiltrates were observed histologically (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Mouse model of MSU-induced acute arthritis.

C57BL/6J mice were injected i.a. with MSU crystals (0.5 mg in 10 μl) in one ankle and vehicle (10 μl PBS) in the contra-lateral ankle. (A and B) Time course and representative photographs (at 24 h) of MSU-induced ankle swelling. (C) H&E-stained sections of ankles at 24 h. (D) Enlargement of the area marked (*) in (C). Insert in (D) shows enlargement of leukocyte infiltrate. Data in (A) are means ± SEM from two independent experiments. *** = P < 0.001 vs. indicated groups by ANOVA. Scale bar in D: 100 μm (insert in D: 10 μm).

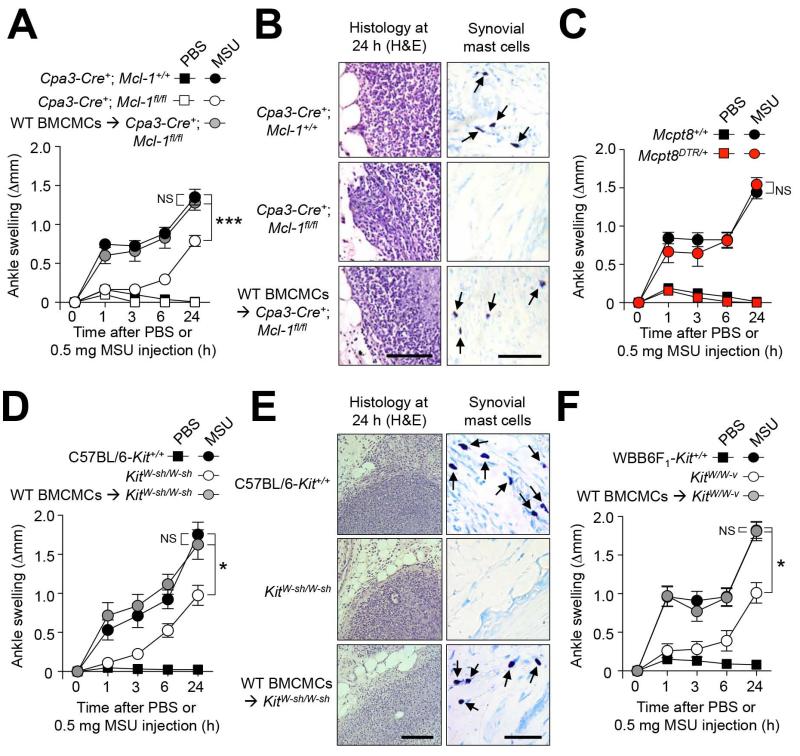

We found that MC- and basophil-deficient Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice (11) developed reduced ankle swelling compared to their littermate controls in this model, especially during the first 3 h of the response, during which little or no response above that induced by PBS was observed in the Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice (Figure 2A). However, substantial ankle swelling (which reached 59 % of that seen in the MSU-injected Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1+/+ mice, as well as leukocyte infiltration, was observed at 24 h in such Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice (Figure 2B). These results indicate that MCs and/or basophils contribute importantly to the early stages of inflammation in this model, and that other cell types also contribute to MSU crystal-induced tissue swelling and leukocyte infiltration, particularly at later intervals after MSU injection.

Figure 2. MCs can amplify MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling.

(A, C, D, F) Changes in ankle thickness after i.a injection of 0.5 mg MSU or PBS in (A) MC- and basophil-deficient Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl (n=17), Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1+/+ littermate (n=20) and C57BL/6J (WT) BMCMC i.a. engrafted Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice (n=10), (C) DT-treated basophil-deficient Mcpt8DTR/+ (n=9) and Mcpt8+/+ littermate (n=9) mice, (D) C57BL/6-Kit+/+ (n=13), MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh (n=12), and C57BL/6J (WT) BMCMC i.a. engrafted KitW-sh/W-sh (n=12) mice, and (F) WBB6F1-Kit+/+ (WT) (n=10), MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/W-v (n=10) and WBB6F1-Kit+/+ (WT) BMCMC i.a. engrafted WBB6F1-KitW/W-v (n=10) mice. (B and E) H&E- (for leukocytes) and Toluidine blue- (for MCs) stained sections of ankles at 24 h. (A, C, D, F) Data are means ± SEM from three (C, D and F) or three to five (A) independent experiments. * or *** = P < 0.05 or 0.001 vs. indicated groups by ANOVA. Scale bars: 100 μm. NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

Because Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice are markedly deficient for both MCs and basophils, we next assessed the relative contribution of these two cell populations in this acute gout model. Basophils can be selectively ablated by injection of diphtheria toxin (DT) into Mcpt8DTR/+ mice (8), which express the DT receptor (DTR) only in basophils. DT-mediated depletion of basophils in Mcpt8DTR/+ mice did not affect MSU-induced ankle swelling (Figure 2C), suggesting that basophils do not importantly contribute to the acute response to MSU crystals.

In contrast, i.a engraftment of Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice with bone marrow-derived cultured MCs from C57BL/6J (WT) mice (WT BMCMCs → Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice) restored MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling to levels observed in Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1+/+ littermate controls, demonstrating an important contribution of MCs (Figure 2A). Such i.a. engraftment with BMCMCs, performed 6 weeks before injection of MSU crystals, restored MC populations locally in the ankle synovium (to ~50 % of the levels observed in WT mice), but no MCs were observed in the contra-lateral ankle joint nor at other locations such as the ear pinna or the spleen. Thus, our results show that local activation of synovial MCs importantly contributes to ankle swelling in this model of acute gout.

MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice also developed significantly diminished ankle swelling compared to C57BL/6-Kit+/+ (WT) mice during the 24 h following i.a. injection of MSU crystals, with the difference from the response in the corresponding WT mice being especially notable at early intervals after MSU injection (Figure 2D). For example, at 1 or 3 h after i.a. injection of MSU crystals, ankle swelling in WT mice was 4.9 fold (at 1 h) or 3.2 fold (at 3 h) those corresponding levels in MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice. By contrast, by 24 h after MSU crystal injection, the corresponding reactions in the WT mice were ~1.8 fold those in the MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice. MSU crystals induced statistically indistinguishable levels of ankle swelling in WT BMCMCs → KitW-sh/W-sh mice and WT mice, further confirming that differences in responses between KitW-sh/W-sh mice and WT mice were due to the lack of MCs in KitW-sh/W-sh mice, as opposed to other c-kit-related abnormalities (14, 15) (Figure 2, D and E). Similarly to the results we obtained with Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice, i.a. engraftment of KitW-sh/W-sh mice with WT (C57BL/6J) BMCMCs restored the MC population locally in the ankle synovium (to ~60% of the levels observed in the corresponding C57BL/6-Kit+/+ mice), but no MCs were observed in the contra-lateral ankle or in the ear pinnae. However, we observed some MCs in the spleen in 3 out of the 9 i.a. MC-engrafted KitW-sh/W-sh mice analyzed, albeit at much lower levels than those observed when such mice are engrafted i.v. with BMCMCs (16-18). Consistent with our findings in Cpa3-Cre+; Mcl-1fl/fl mice, MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice also developed substantial leukocyte infiltration at 24 h after injection of MSU crystals (Figure 2E). We obtained very similar results using c-kit mutant WBB6F1-KitW/W-v mice, the corresponding WBB6F1-Kit+/+ (WT) mice, and MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/W-v mice engrafted i.a. with WBB6F1-Kit+/+ BMCMCs (Figure 2F). Together, these results demonstrate that MCs can contribute significantly to the acute tissue swelling response to i.a. injection of MSU crystals in mice, especially at early intervals after challenge with MSU.

Roles of the NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-1R1 and IL-1β

We then analyzed in more detail the mechanism by which MSU crystals induce ankle swelling in mice. The NLRP3 inflammasome (composed of NLRP3, ASC and Caspase-1) can convert pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms, and is thought to play a central role in gout through production of IL-1β (19, 20). We found that Nlrp3−/−, ASC−/−, and Caspase-1−/− mice each developed diminished ankle swelling in this model compared to WT mice, especially at early intervals after injection of MSU crystals (Figure 3, A and B), but they still developed both substantial ankle swelling and acute inflammatory infiltrates by 24 h (Figure 3, A and B and data not shown). Thus, our results show that both NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent and NLRP3 inflammasome-independent pathways likely mediate the acute arthritis in this mouse model.

We also found, using mice deficient in the IL-1 receptor, IL-1R1, or IL-18 that IL-1R1 but not IL-18 contributes to MSU crystal-induced acute ankle swelling (Figure 3C). However, similar to mice deficient for components of the NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-1R1−/− mice developed substantial tissue swelling and acute inflammatory infiltrates by 24 h after injection of MSU crystals (Figure 3C and data not shown). Although TNF is not a product of the NLRP3 inflammasome, because of the importance of TNF in other models of MC-dependent inflammation (4), we also assessed the potential role of this cytokine in MSU-induced inflammation. However, we observed similar MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling (Figure 3C) in WT and TNF−/− mice.

IL-1R1 is the receptor for both IL-1α and IL-1β. We did not detect any significant difference between WT and IL-1α−/− mice in this model (Figure 3D). By contrast, we found a clear role for IL-1β in the acute response to i.a. injection of MSU crystals (Figure 3D).

MC-derived IL-1β contributes to MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling

Because IL-1β can be derived from many different cell types, we assessed the importance of MCs as a source of IL-1β in this model using MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice engrafted i.a. with C57BL/6J (WT) BMCMCs in one ankle joint and C57BL/6-IL-1β−/− BMCMCs in the contra-lateral ankle. Six weeks after MC engraftment, we injected MSU crystals into both ankles. We found that MSU crystal-induced swelling in the ankle engrafted with WT BMCMCs was very similar to that observed in C57BL/6-Kit+/+ (WT) mice, whereas swelling in the ankle engrafted with IL-1β−/− BMCMCs was significantly diminished and statistically indistinguishable from levels of swelling in MC-deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice not engrafted with BMCMCs (Figure 4A). We observed very similar anatomical distributions and numbers of MCs in the ankles of KitW-sh/W-sh mice engrafted with WT or IL-1β−/− BMCMCs, indicating that the observed differences in MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling did not simply reflect differences in MC numbers or distribution between such ankles. We obtained very similar results when we tested MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/W-v mice, the corresponding WBB6F1-Kit+/+ WT mice, and MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/W-v mice engrafted with C57BL/6J WT or C57BL/6-IL-1β−/− BMCMCs (Figure 4B). Taken together, our results support an important role for MC-derived IL-1β in the early stages of the tissue swelling response to i.a. injection of MSU crystals.

Local ablation of MCs reduces MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling

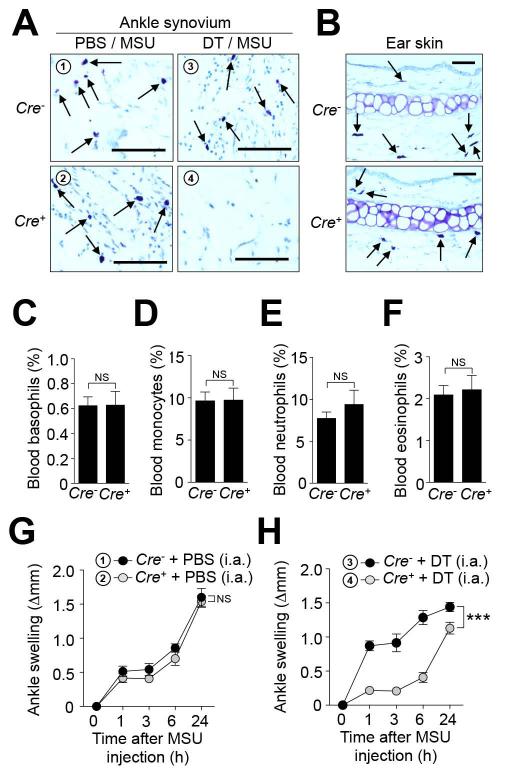

We next designed experiments to evaluate the potential therapeutic benefit of targeting MCs in gout. Because drugs that solely and specifically suppress MC activation have not yet been reported, we developed an alternative experimental strategy to deplete MCs selectively. We mated Cpa3-Cre transgenic mice (which express Cre under the control of the MC-associated Carboxypeptidase A3 promoter) (11, 14) to iDTRfl/fl mice which bear a Cre-inducible DTR. We performed local (i.a.) injection of low doses of DT in an attempt to achieve selective ablation of synovial MCs. Such treatment resulted in a marked depletion of MCs in the ankle joint of Cre+ mice but not in Cre− mice (Figure 5A). The MC depletion was local, and appeared to be specific for MCs, since i.a. injection of DT did not affect numbers of MCs in the contra-lateral PBS-treated ankle joint (Figure 5A) or ear pinna, nor were blood basophils, neutrophils, eosinophils or monocytes affected (Figure 5, B-F). Using this approach, we found that local ablation of MCs can significantly reduce ankle swelling in the gout model (Figure 5, G and H).

Figure 5. Local and selective ablation of MCs reduces MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling.

Cpa3-Cre+; DTRfl/+ (Cre+; n=13) and Cpa3-Cre−; DTRfl/+ (Cre−; n=7) mice were injected i.a. with diphtheria toxin (DT) (two successive weekly injections of 50 ng) in one ankle and vehicle (PBS) in the contralateral ankle. 0.5 mg MSU was injected into both ankles 1 week after the last DT injection. (A and B) Toluidine-blue staining of ankle joint tissue (A) showing ablation of synovial MCs after treatment with DT (but not PBS) in Cre+ mice and the presence of MCs in ear skin (B) in either Cre− or Cre+ mice. Scale bars: 50 μm. (C-F) Blood leukocytes isolated 1 h before MSU injection were analyzed by flow cytometry. (C-F) % (mean + SEM) of (C) basophils (CD49b+; IgE+), (D) monocytes (Gr-1low; CD11b+; Siglec-F−), (E) neutrophils (Gr-1high; CD11b+; Siglec-F−) & (F) eosinophils (SSChigh; Siglec-F+). NS, not significant (P > 0.05 by unpaired Student’s t test). (G and H) Changes in ankle thickness (means ± SEM) after i.a injection of MSU. Data are shown as means ± SEM from two (for Cre− mice) or three (for Cre+ mice) independent experiments. *** = P < 0.001 vs. indicated group by ANOVA.

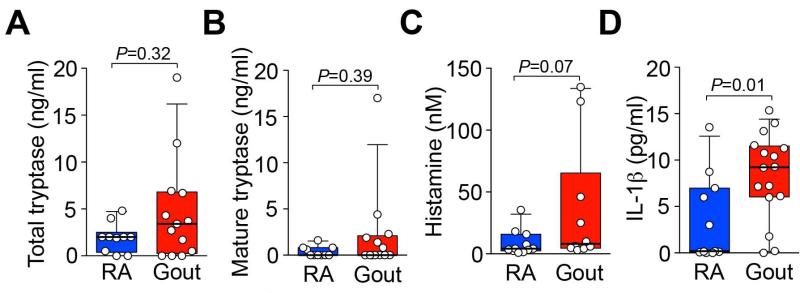

Detection of tryptase, histamine, and IL-1βin synovial fluids of patients with gout

Finally, we searched for evidence of local activation of MCs during acute attacks of gout by measuring levels of tryptase and histamine (two mediators stored in MC granules and released upon MC degranulation) in synovial fluids from patients requiring joint aspiration for relief of a symptomatic gout flare. Because obtaining biopsies of synovial tissues in this setting is not clinically indicated, we were not able directly to analyze MCs in joint synovium. We compared levels of tryptase, histamine, and IL-1β in synovial fluids from patients with acute gout to those found in synovial fluids from patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a disease known to be associated with MC activation (21).

Mature tryptase (retained by MCs until they are activated to degranulate) and total tryptase (comprised of mature tryptase and protryptase [spontaneously secreted by resting MCs]) (22), as well as histamine, were present in synovial fluids from gout patients at levels similar to those in specimens from subjects with RA (Figure 6, A-C). These results support the conclusion that MCs are locally activated during acute attacks of gout in humans. In addition, synovial fluids of gout patients had significantly higher levels of IL-1β than did those of RA patients (Figure 6D), consistent with the known central role for this cytokine in gouty inflammation (6, 23, 24).

Figure 6. Levels of tryptase, histamine and IL-1β in synovial fluids from patients with gout or rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Levels of total (A) and mature (B) tryptase, histamine (C) and IL-1β (D) measured by ELISA in synovial fluids from patients with RA (n=10-11) or gout (n=10-16). Data are represented as box and whisker plots with bottom and top of the boxes showing the 25th & 75th percentiles and bars showing the 10th & 90th percentiles; individual data are plotted as circles. P values were calculated using a Mann-Whitney test.

DISCUSSION

While it has been reported that MCs infiltrate gouty tophi (25), little is known about the actual roles of MCs either in that setting or during acute attacks of gout. Similarly, prior studies have linked MC activation and MSU crystal-induced acute inflammation in rat air pouches (26) or in the mouse peritoneal cavity (27), but there have been no prior reports analyzing the contributions of MCs to MSU crystal-induced acute arthritis. We therefore developed a mouse model of MSU crystal-induced acute arthritis and, using that model, identified several lines of evidence supporting the conclusion that MC activation importantly contributes to the development of MSU crystal-induced acute arthritis.

Because studies performed using various models of antibody-dependent arthritis obtained conflicting results when tested in different strains of MC-deficient mice (15, 28,29), we have suggested that definitive investigation of the possible roles MCs in mouse models of disease ideally should be assessed using at least two different strains of MC-deficient mice, including one which lacks mutations affecting c-KIT structure or expression (14). Using this approach, we showed that MSU crystal-induced ankle swelling was significantly reduced in two types of c-kit mutant MC-deficient mice (KitW/W-v and KitW-sh/W-sh mice), as well as in c-kit-independent MC- and basophil-deficient Cpa3-Cre; Mcl-1fl/fl mice (11, 14), but not in basophil-deficient Mcpt8DTR mice (8). We also showed that engraftment of c-kit-mutant MC-deficient mice with wild type MCs locally in the ankle joint was sufficient to restore WT levels of MSU crystal-induced acute ankle swelling.

It is now well established that MSU crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro leading to production of IL-1β and IL-18 (2), but controversial results have been obtained regarding the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammation induced by injections of MSU crystals in vivo (2, 30-33). While all reports agree on a significant role for ASC, Caspase-1 and IL-1R1, some reports (30, 33), but not others (31, 32), support an important role for NLRP3. We found that, like MC-deficient mice, Nlrp3−/−, ASC−/−,Caspase-1−/− and IL-1R1−/− mice developed significantly lower levels of ankle swelling than did WT mice at early intervals after i.a. injection of MSU crystals, but still exhibited substantial tissue swelling and leukocyte infiltration by 24 h after injection of the crystals. Thus, our results show that both inflammasome-dependent and inflammasome-independent pathways likely mediate tissue swelling in this model of MSU crystal-induced acute arthritis.

Previous reports have demonstrated roles for IL-1β in MSU crystal-induced inflammation in mice (30, 31) and for IL-1α in mediating neutrophil recruitment after i.p. injection of MSU (32). We confirmed the latter finding using i.p. injection of MSU crystals in IL-1α−/− mice (data not shown) but did not detect any significant difference between WT and IL-1α−/− mice in our model. By contrast, we found a clear role for IL-1β in the acute response to i.a. injection of MSU crystals.

Many cell types can produce IL-1β, including MCs (5), macrophages (34), dendritic cells (35) and neutrophils (36). MC-derived IL-1β was implicated in a model of antibody-dependent arthritis studied in KitW/W-v mice which had been systemically engrafted with BMCMCs (5). Here we show, using local engraftment of the ankle with WT or IL-1β−/− BMCMCs in two types of c-kit-mutant MC-deficient mice (KitW/W-v and KitW-sh/W-sh mice), that MC-derived IL-1β can contribute importantly to MSU crystal-induced acute ankle swelling in this model.

Our results indicate that MCs contribute importantly to the early stages of inflammation in this acute gout model, but that other cell types also contribute to MSU crystal-induced tissue swelling and leukocyte infiltration, particularly at later intervals after MSU injection. Among the potential resident inflammatory cells that could also mediate arthritis in this model, macrophages have been shown to produce IL-1β through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome after stimulation with MSU crystals in vitro (2). Moreover, depletion of macrophages by pretreatment with clodronate liposomes reduces the inflammatory response induced by intraperitoneal injection of MSU crystals (37).

Previous reports have shown that human and mouse MCs also express components of the NLRP3 inflammasome and can produce IL-1β in response to co-stimulation with LPS and ATP (38, 39). However, we could not detect significant IL-1β release in either mouse BMCMCs or primary human peripheral blood-derived cultured MCs (40) when stimulated with MSU crystals (alone, or after overnight priming with LPS) (data not shown). While important differences probably exist between such ex vivo-derived cultured MCs and the endogenous MCs present in synovial tissues, our results suggest that mouse synovial MCs in their natural microenvironment may be more responsive to MSU crystals than are ex vivo-derived mast cells, that synovial MCs are stimulated indirectly by another MSU-sensitive cell, and/or that multiple stimuli are required to elicit MC activation and IL-1β secretion upon MSU exposure.

To assess the potential therapeutic benefit of targeting MCs in gout, we developed a new strain of mice, Cpa3-Cre; iDTRfl/+ mice, in which local injection of DT results in selective ablation of MCs in the ankle joint. We showed that such local ablation of MCs significantly reduced ankle swelling in the model, validating the hypothesis that MCs represent an important therapeutic target in this model of MSU-induced acute arthritis.

Finally, we searched for evidence of MC activation in human gout. MC-associated mediators such as histamine and tryptase have been detected in synovial fluids from RA patients, findings which have been interpreted as consistent with MC activation in this setting (41, 42). Both histamine and tryptase are stored in MC granules and can be released upon MC activation. MCs are the major source of histamine in tissues, however several other cell types can also produce histamine, including basophils (43) and neutrophils (44). Tryptase is a more specific (and stable) marker of MC activation (45). We confirmed the presence of both histamine and tryptase in synovial fluids from RA patients and show that similar levels of these MC-associated mediators are found in synovial fluids obtained during acute attacks of gout. These results suggest that local MC activation occurs during acute gout attacks in humans. We also showed that synovial fluids from patients with acute gout contained significantly higher levels of IL-1β than did RA synovial fluids, consistent with an important role for IL-1β in gout (46-48).

In summary, our findings indicate that MCs and MC-derived IL-1β importantly contribute to the tissue swelling observed at early intervals after intra-articular injection of MSU crystals. Although care should be taken in extrapolating results obtained in mice to humans, our findings raise the possibility that even transient inhibition of MC activation may confer benefit in acute gout.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Drs. Denise Monack (Stanford University) and Vishva Dixit (Genentech) for generously providing Caspase-1−/−, Nlrp3−/− and ASC−/− mice, and Chen Liu and Mariola Liebersbach for excellent technical assistance.

Declaration of funding sources:

L.L.R. and N.G. are recipients of fellowships from the French “Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale FRM”. T.M. is supported by a fellowship from the Belgium American Educational Foundation and a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship for Career Development: 299954. P.S. is supported by a Max Kade Fellowship of the Max Kade Foundation and the Austrian Academy of Sciences and a Schroedinger Fellowship of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): J3399-B21. J.S. is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Arthritis Foundation, and the William C. Kuzell Foundation. W.H.R.’s work is supported by NIH R01-AI085268-01 and the Department of Veterans Affairs. L.B.S’s work was supported by NIH U19AI077435. This work was supported by grant SPO106496 from the Arthritis National Research Foundation (to L.L.R.) and National Institutes of Health grants AI023990, CA072074 and AI070813 (to S.J.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440(7081):237–41. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CJ, Shi Y, Hearn A, Fitzgerald K, Golenbock D, Reed G, et al. MyD88-dependent IL-1 receptor signaling is essential for gouty inflammation stimulated by monosodium urate crystals. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2262–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI28075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham SN, St John AL. Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(6):440–52. doi: 10.1038/nri2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nigrovic PA, Binstadt BA, Monach PA, Johnsen A, Gurish M, Iwakura Y, et al. Mast cells contribute to initiation of autoantibody-mediated arthritis via IL-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(7):2325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610852103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schumacher HR, Jr., Sundy JS, Terkeltaub R, Knapp HR, Mellis SJ, Stahl N, et al. Rilonacept (interleukin-1 trap) in the prevention of acute gout flares during initiation of urate-lowering therapy: results of a phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):876–84. doi: 10.1002/art.33412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piliponsky AM, Chen CC, Grimbaldeston MA, Burns-Guydish SM, Hardy J, Kalesnikoff J, et al. Mast cell-derived TNF can exacerbate mortality during severe bacterial infections in C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(2):926–38. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wada T, Ishiwata K, Koseki H, Ishikura T, Ugajin T, Ohnuma N, et al. Selective ablation of basophils in mice reveals their nonredundant role in acquired immunity against ticks. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(8):2867–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI42680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horai R, Asano M, Sudo K, Kanuka H, Suzuki M, Nishihara M, et al. Production of mice deficient in genes for interleukin (IL)-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-1alpha/beta, and IL-1 receptor antagonist shows that IL-1beta is crucial in turpentine-induced fever development and glucocorticoid secretion. J Exp Med. 1998;187(9):1463–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korner H, Cook M, Riminton DS, Lemckert FA, Hoek RM, Ledermann B, et al. Distinct roles for lymphotoxin-alpha and tumor necrosis factor in organogenesis and spatial organization of lymphoid tissue. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27(10):2600–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lilla JN, Chen CC, Mukai K, BenBarak MJ, Franco CB, Kalesnikoff J, et al. Reduced mast cell and basophil numbers and function in Cpa3-Cre; Mcl-1fl/fl mice. Blood. 2011;118(26):6930–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrer M, Nunez-Cordoba JM, Luquin E, Grattan CE, De la Borbolla JM, Sanz ML, et al. Serum total tryptase levels are increased in patients with active chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(12):1760–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reber LL, Marichal T, Galli SJ. New models for analyzing mast cell functions in vivo. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(12):613–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou JS, Xing W, Friend DS, Austen KF, Katz HR. Mast cell deficiency in Kit(W-sh) mice does not impair antibody-mediated arthritis. J Exp Med. 2007;204(12):2797–802. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hershko AY, Suzuki R, Charles N, Alvarez-Errico D, Sargent JL, Laurence A, et al. Mast cell interleukin-2 production contributes to suppression of chronic allergic dermatitis. Immunity. 2011;35(4):562–71. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimbaldeston MA, Chen CC, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Tam SY, Galli SJ. Mast cell-deficient W-sash c-kit mutant KitW-sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(3):835–48. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62055-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reber LL, Marichal T, Mukai K, Kita Y, Tokuoka SM, Roers A, et al. Selective ablation of mast cells or basophils reduces peanut-induced anaphylaxis in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(4):881–8. e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Flavell R. Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature. 2012;481(7381):278–86. doi: 10.1038/nature10759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010;327(5963):296–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1184003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nigrovic PA, Lee DM. Synovial mast cells: role in acute and chronic arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:19–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz LB, Min HK, Ren S, Xia HZ, Hu J, Zhao W, et al. Tryptase precursors are preferentially and spontaneously released, whereas mature tryptase is retained by HMC-1 cells, Mono-Mac-6 cells, and human skin-derived mast cells. J Immunol. 2003;170(11):5667–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran TH, Pham JT, Shafeeq H, Manigault KR, Arya V. Role of Interleukin-1 Inhibitors in the Management of Gout. Pharmacotherapy. 2013 doi: 10.1002/phar.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J. A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2):R28. doi: 10.1186/ar2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SJ, Nam KI, Jin HM, Cho YN, Lee SE, Kim TJ, et al. Bone destruction by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand-expressing T cells in chronic gouty arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(5):R164. doi: 10.1186/ar3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiltz C, Liote F, Prudhommeaux F, Meunier A, Champy R, Callebert J, et al. Monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced inflammation in vivo: quantitative histomorphometric analysis of cellular events. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(6):1643–50. doi: 10.1002/art.10326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Getting SJ, Flower RJ, Parente L, de Medicis R, Lussier A, Woliztky BA, et al. Molecular determinants of monosodium urate crystal-induced murine peritonitis: a role for endogenous mast cells and a distinct requirement for endothelial-derived selectins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283(1):123–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feyerabend TB, Weiser A, Tietz A, Stassen M, Harris N, Kopf M, et al. Cre-mediated cell ablation contests mast cell contribution in models of antibody- and T cell-mediated autoimmunity. Immunity. 2011;35(5):832–44. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee DM, Friend DS, Gurish MF, Benoist C, Mathis D, Brenner MB. Mast cells: a cellular link between autoantibodies and inflammatory arthritis. Science. 2002;297(5587):1689–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1073176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amaral FA, Costa VV, Tavares LD, Sachs D, Coelho FM, Fagundes CT, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neutrophil recruitment and hypernociception depends on leukotriene B4 in a murine model of gout. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:474–84. doi: 10.1002/art.33355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joosten LA, Netea MG, Mylona E, Koenders MI, Malireddi RK, Oosting M, et al. Engagement of fatty acids with Toll-like receptor 2 drives interleukin-1beta production via the ASC/caspase 1 pathway in monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(11):3237–48. doi: 10.1002/art.27667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross O, Yazdi AS, Thomas CJ, Masin M, Heinz LX, Guarda G, et al. Inflammasome activators induce interleukin-1alpha secretion via distinct pathways with differential requirement for the protease function of caspase-1. Immunity. 2012;36(3):388–400. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffman HM, Scott P, Mueller JL, Misaghi A, Stevens S, Yancopoulos GD, et al. Role of the leucine-rich repeat domain of cryopyrin/NALP3 in monosodium urate crystal-induced inflammation in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):2170–9. doi: 10.1002/art.27456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Dubyak GR, Nunez G. Differential requirement of P2X7 receptor and intracellular K+ for caspase-1 activation induced by intracellular and extracellular bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(26):18810–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghiringhelli F, Apetoh L, Tesniere A, Aymeric L, Ma Y, Ortiz C, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1beta-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat Med. 2009;15(10):1170–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho JS, Guo Y, Ramos RI, Hebroni F, Plaisier SB, Xuan C, et al. Neutrophil-derived IL-1beta is sufficient for abscess formation in immunity against Staphylococcus aureus in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(11):e1003047. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin WJ, Walton M, Harper J. Resident macrophages initiating and driving inflammation in a monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced murine peritoneal model of acute gout. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(1):281–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura Y, Franchi L, Kambe N, Meng G, Strober W, Nunez G. Critical role for mast cells in interleukin-1beta-driven skin inflammation associated with an activating mutation in the nlrp3 protein. Immunity. 2012;37(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura Y, Kambe N, Saito M, Nishikomori R, Kim YG, Murakami M, et al. Mast cells mediate neutrophil recruitment and vascular leakage through the NLRP3 inflammasome in histamine-independent urticaria. J Exp Med. 2009;206(5):1037–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaudenzio N, Laurent C, Valitutti S, Espinosa E. Human mast cells drive memory CD4+ T cells toward an inflammatory IL-22+ phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(5):1400–7. e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buckley MG, Walters C, Wong WM, Cawley MI, Ren S, Schwartz LB, et al. Mast cell activation in arthritis: detection of alpha- and beta-tryptase, histamine and eosinophil cationic protein in synovial fluid. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997;93(4):363–70. doi: 10.1042/cs0930363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malone DG, Irani AM, Schwartz LB, Barrett KE, Metcalfe DD. Mast cell numbers and histamine levels in synovial fluids from patients with diverse arthritides. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):956–63. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sampson D, Archer GT. Release of histamine from human basophils. Blood. 1967;29(5):722–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu X, Zhang D, Zhang H, Wolters PJ, Killeen NP, Sullivan BM, et al. Neutrophil histamine contributes to inflammation in mycoplasma pneumonia. J Exp Med. 2006;203(13):2907–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz LB, Metcalfe DD, Miller JS, Earl H, Sullivan T. Tryptase levels as an indicator of mast-cell activation in systemic anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. New Engl J Med. 1987;316(26):1622–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706253162603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalbeth N. Gout in 2010: progress and controversies in treatment. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2011;7(2):77–8. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rock KL, Kataoka H, Lai JJ. Uric acid as a danger signal in gout and its comorbidities. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(1):13–23. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dinarello CA. How interleukin-1beta induces gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(11):3140–4. doi: 10.1002/art.27663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.