Abstract

Background. Heparin, used clinically as an anticoagulant, also has anti-inflammatory properties. The purpose of this systematic review was to provide a comprehensive review regarding the efficacy and safety of heparin and its derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents. Methods. We searched the following databases up to March 2012: Pub Med, Scopus, Web of Science, Ovid, Elsevier, and Google Scholar using combination of Mesh terms. Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) and trials with quasi-experimental design in clinical setting published in English were included. Quality assessments of RCTs were performed using Jadad score and Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist. Results. A total of 280 relevant studies were reviewed and 57 studies met the inclusion criteria. Among them 48 studies were RCTs. About 65% of articles had score of 3 and higher according to Jadad score. Twelve studies had a quality score > 40% according to CONSORT items. Asthma (n = 7), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 5), cardiopulmonary bypass (n = 8), and cataract surgery (n = 6) were the most studied disease condition. Forty studies use unfractionated heparin (UFH) for intervention; the remaining studies use low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). Conclusion. Despite the conflicting results, heparin seems to be a safe and effective anti-inflammatory agent; although it is shown that heparin can decrease the level of inflammatory biomarkers and improves patient conditions, still more data from larger rigorously designed studies are needed to support use of heparin as an anti-inflammatory agent in clinical setting. However, because of the association between inflammation, atherogenesis, thrombogenesis, and cell proliferation, heparin and related compounds with pleiotropic effects may have greater therapeutic efficacy than compounds acting against a single target.

1. Introduction

Heparin is a highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) that is found in the mast cells of most mammals. The endogenous GAGs are highly acidic and actively charged. Heparin is the most sulfated, and acidic GAGs enable it to bind to different component such as coagulating and fibrinolysing proteins, many growth factors, and immune response proteins such as cytokines and chemokines [1, 2]. Heparin is mostly known for its anticoagulant properties, so commercially form of heparin including unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) used currently in treatment and prevention of thrombotic events like deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary emboli, acute coronary syndromes, and ischemic cerebrovascular events as well as prevention of thrombosis in extracorporeal circuits and hemodialysis [3, 4]. Apart from its anticoagulant effects, there are several studies which have shown that heparin possesses various anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties and the mechanisms of anti-inflammatory actions of heparin have been discussed recently [5, 6]. But the exact benefit and safety of heparin and its derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents in clinical setting have not definitely proved yet. Our objective was to systematically review and summarize the literature supporting anti-inflammatory role of heparin to provide evidence about the clinical effectiveness and safety of heparin in inflammatory conditions.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Ovid, Elsevier, and Google Scholar from inception to March 2012 using the following Mesh keywords: (1) heparin, (2) UFH, (3) anticoagulants, (4) dalteparin, (5) enoxaparin, (6) nadroparin, (7) tinzaparin, (8) heparinoids, (9) inflammation, (10) inflammatory process, (11) anti-inflammation, (12) inflammation mediators, (13) inflammatory bowel disease, and (14) anti-inflammatory agents. All keywords from 1 to 8 were separately combined with each keyword from 9 to 14 in all databases. Articles were initially scanned based on titles and abstracts by two reviewers (Sarah Mousavi and Mandana Moradi) and related articles were retrieved in full and assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (Sarah Mousavi and Mandana Moradi). The reference list of each eligible study was checked to identify additional studies.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

All Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) and studies with quasi-experimental design which evaluated efficacy, using inflammatory biomarkers levels, and safety (significant hemorrhage or thrombocytopenia) of anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and heparin-related derivatives (LMWH or other heparinoids) with an English abstract regardless of rout of administration (intravenous, subcutaneous, topical, or inhaler), age, gender, race, and ethnic origin of participants were included.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

The following were excluded: studies based on animal models; preclinical and biological studies, letters, and editorials; report published as meeting abstract only; where insufficient data were reported to allow inclusion.

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data from each eligible study were extracted individually and compared by two authors (Sarah Mousavi and Mandana Moradi) using standard form that included study design, setting, sample size, duration and follow up, dosing regimen, intervention type, and outcomes. Disagreements were resolved through discussion; if necessary they consulted a third person. A narrative synthesis was conducted.

Quality assessment of clinical trials included in the analysis were performed utilizing the Jadad score, a previously validated instrument that assesses trials based on appropriate randomization, blinding, and description of study withdrawals or dropouts [7]. The description of this score is as follows: (1) whether it is randomized (yes = 1 point, no = 0); (2) whether randomization was described appropriately (yes = 1 point, no = 0); (3) whether it is double-blind (yes = 1 point, no = 0); (4) whether the double-blinding was described appropriately (yes = 1 point, no = 0); (5) whether withdrawals and dropouts were described (yes = 1 point, no = 0). The quality score ranges from 0 to 5 points; a low-quality report score is ≤2; and a high-quality report score is at least 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist was also used for randomized trials as it is strongly endorsed by prominent journals and leading editorial organizations [8]. Total possible score for CONSORT checklist was considered as 74: two points for adequate description, one point for inadequate description, and zero for no description.

2.5. Statistical Methods

To summarize and extract data, the database was designed by Microsoft office Access 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). A narrative synthesis was conducted and data were extracted into tables and summarized.

3. Results

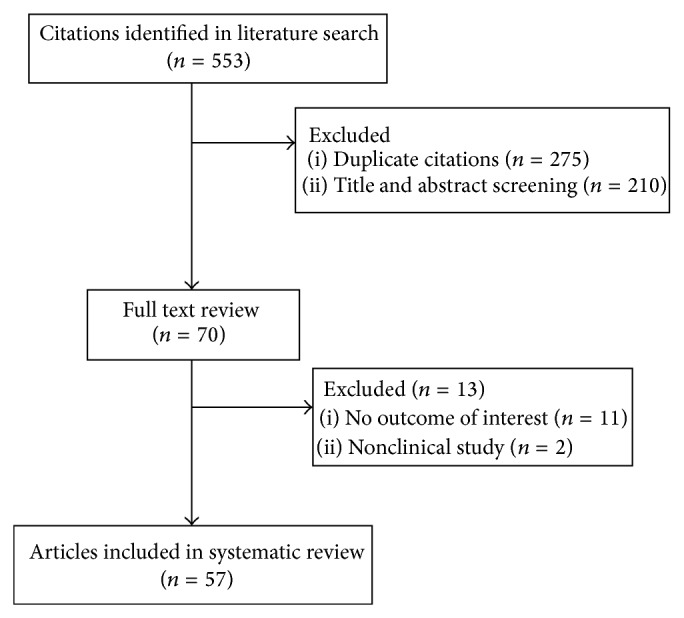

Following Initial screening of mentioned databases total of 553 citations (275 duplicates) were extracted but only 70 of them were potentially eligible for investigation of our objectives (according to our proposed inclusion criteria) based on titles and abstracts. The full text screening excluded other 13 citations and the remaining 57 papers were considered relevant for data extraction and following analysis. The flow chart of studies' selection processes is as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search process.

3.1. Study and Patient Characteristic

Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 555 patients in 57 studies that met the criteria to be included. Research designs mostly were randomized controlled trial (n = 48) and the remaining (n = 9) had quasi-experimental designs using pre-post studies (n = 6).

Tables 1 and 2 [9–62] list the characteristics of the included studies. The most studied clinical conditions was cardiopulmonary bypass (n = 12), followed by Asthma (n = 8), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (n = 5), acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (n = 8), and ophthalmological disease (n = 8). Other less common studied conditions were as follows: burn, cystic fibrosis, allergic rhinitis, superficial thrombophlebitis, and hemodialysis. Unfractionated heparin (UFH) was used in forty studies as subcutaneous, intravenous, inhaler, or heparin-coated circuits while others used enoxaparin (n = 3), dalteparin (n = 4), nadroparin (n = 4), and tinzaparin (n = 1).

Table 1.

Summary and findings of common studied diseases.

| Clinical setting | Heparin preparation | Mode of administration | Comparator | Number of patients | Clinical outcome | Laboratory outcome | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise-induced Asthma [9] | UFH | Inhaler | Cromolyn sodium or placebo | 12 | Significantly reduction of exercise-induced asthma | Heparin had no effect on histamine-induced bronchoconstriction | Single-blind, randomized, crossover clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Asthma [10] | UFH | Inhaler | Placebo | 8 | Significant reduction of late asthmatic response after allergen administration (P: 0.005) | — | Randomized, double-blind, crossover clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Atopic asthma [11] | Heparin (IVX-0142) | Nebulizer | Placebo | 19 | No significant decrease in early (P: 0.06) and late (P: 0.24) asthmatic response | — | Randomized single-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial |

|

| |||||||

| Asthma [12] | LMWH | Nebulizer | — | 24 | Effective as an add-on therapy to standard treatment | Reduction in eosinophil (P: 0.0006) and lymphocyte (P: 0.049) in bronchoalveolar lavage. No changes in IL-5 or ECP concentrations in serum | Quasi-experimental (pretest-posttest design) |

|

| |||||||

| Allergic asthma [13] | UFH | Inhaler | Placebo | 25 | Heparin inhalation significantly reduced bronchial hyperreactivity (P < 0.05) | — | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial |

|

| |||||||

| Asthma [14] | UFH | Inhaler | — | 12 | Transient (time-dependent) inhibitory role in allergic reactions | Increased the methacholine PC20 value (P: 0.05) but did not prevent an increase in Raw and/or a decrease in SGAW | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial |

|

| |||||||

| Asthma (children) [15] | UFH | Inhaler | Placebo | 14 | Single dose of heparin significantly (P: 0.005) reduced bronchial hyperreactivity | Provocation test used leukotriene D4 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial |

|

| |||||||

| Asthma [16] | UFH | Inhaler | Placebo | 23 | Significant reduction of bronchial hyperreactivity to histamine and leukotriene | — | Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, crossover trial |

|

| |||||||

| IBD [17] | UFH | IV/SC | Hydrocortisone + prednisolone | 20 (12 in control group) | Clinical activity index, stool frequency, and endoscopic and histopathological grading were similar in both treatment groups | CRP and α1 acid glycoprotein did not change | Open label randomized, crossover clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| IBD [18] | UFH | SC | — | 17 | Histology improved significantly in ulcerative colitis patients (UFH is effective in ulcerative colitis but not Crohn disease) | CRP (P: 0.0119) and ESR (P: 0.0096) significantly reduced in ulcerative colitis but not Crohn disease | Quasi-experimental (pretest-posttest design) |

|

| |||||||

| IBD [19] | UFH | IV | Methyl prednisolone | 25 (13 in control group) | No effect of heparin, also increased bleeding | No change in CRP | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial |

|

| |||||||

| IBD [20] | Enoxaparin + standard treatment | SC | Aminosalicylate + corticosteroid | 34 (18 in control group) | Significant improvement in disease severity in both groups (P: 0.001) | No difference ESR, CRP and fibrinogen and coagulation | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| IBD [21] | Nadroparin | SC | — | 25 | Endoscopic and histological sign of inflammation significantly improved | — | Quasi-experimental (Non-randomized clinical trial) |

|

| |||||||

| Cataract surgery [22] | UFH | Intraocular lens (IOL) | Polymethylmethacrylate | 524 | — | Heparin surface modification reduced the cellular deposit compared to control group | Randomized, double-blind, parallel group clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cataract surgery [23] | UFH | Intraocular lens (IOL) | Polymethylmethacrylate | 58 (31 in control group) | Postoperative inflammation decreased significantly in heparin group (P: 0.02) | Giant cell and cell deposit decreased significantly (P < 0.05) | Randomized, double-blind, clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cataract surgery (pediatric) [24] | UFH | Irrigation | Balanced salt solution | 33 (19 in control group) | Heparin irrigation reduced number of postoperative inflammatory related complication | Anterior chamber reaction including fibrin formation was lower in heparin group | Randomized prospective double-blind trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cataract surgery (pediatrics) [25] | Enoxaparin | Irrigation | No treatment | 40 (20 in each group) | Increase of flare and cell deposit after surgery (1 and 3 months) (P: 0.99) | Increase in large cell deposits | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cataract surgery [26] | UFH | Irrigation | Regular irrigation solution | 72 | Significant reduction of inflammation in the early (days 1–3) postoperative period (P < 0.01) | — | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass (pediatric) [27] | Heparin-coated circuit (n = 11) | — | Non-heparin-coated circuit (n = 10) | 21 | Decrease of systemic inflammatory response with the use of heparin-bonded oxygenators | Significantly decreased levels of IL-6, IL-8, terminal complement complex, neutrophils, and elastase in heparin coated circuit | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass [28] | Heparin-coated circuit ± aprotinin | — | Uncoated circuit ± aprotinin | 200 (4 groups) | Aprotinin and heparin had no effect on cytokine release | TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 and myeloperoxidase did not change | Randomized, double-blind, clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass [29] | UFH | — | Uncoated circuit | 51 (26 in each group) | Decreased pulmonary vascular resistance index and pulmonary shunt fraction, and increased PaO2/FIO2 ratio | Lower levels of phospholipase A2 and complement activation (P: 0.001) | Randomized, double-blind, clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass [30] | Heparin-coated circuit | — | Non-heparin-coated circuit | 16 (9 in control group) | — | No significant difference between groups regarding: granulocyte elastase IL-6, IL-8 | Quasi-experimental (pretest-posttest design) |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass [31] | Heparin concentration-based system | — | Activated clotting time-based management | 200 (100 in control group) | No effect on postoperative blood loss | Significant reduction of neutrophil activation and fibrinolysis and thrombin generation (P < 0.05) | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass (pediatric) [32] | Heparin-coated circuit | — | Non-heparin-coated circuit | 19 (10 in control group) | Improvement of the biocompatibility of CPB during heart surgery | Levels of complement factor C3a (P < 0.001) and IL-6 (P: 0.005) significantly reduced in heparin-coated circuit | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass (pediatric) [33] | Heparin-coated circuit | — | Non-heparin-coated circuit | 34 (12 in control group) | No differences in duration of intubation, intensive care unit or hospital stay, or postoperative blood loss | IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were significantly lower in heparin group (P < 0.01, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, resp.) | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass [34] | Heparin-coated circuit (heparin + aprotinin) | — | Non-heparin-coated circuit (heparin + aprotinin) | 30 (15 in each group) | No significant differences between the two groups in terms of bleeding and transfusional requirements, the time spent on a ventilator, or in duration of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) | Levels of IL-6, CRP, and neutrophil count did not change by heparin-coated circuit. Monocyte count increased in heparin-coated circuit | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) [35] | Heparin-coated circuit | — | Non-heparin-coated circuit | 18 (9 in each group) | — | Reduction of levels of IL-8 and TNF-α and increase of neutrophil elastase | Randomized controlled trial |

CRP: C-Reactive Protein, CPB: Cardio Pulmonary Bypass, ECP: Eosinophil Cationic Protein, ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation, ICU: Intensive Care Unit, IL: interleukin, IV: intravenous, SC: subcutaneous, SGAW: Specific Airway Conductance, TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor, and UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Table 2.

Summary and findings of other studied diseases.

| Clinical setting | Heparin preparation | Mode of administration | Comparator | Number of patients | Clinical outcome | Laboratory outcome | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatitis after ERCP [36] | UFH | SC | Saline solution | 105 (54 in control group) | Rate of postoperative pancreatitis was not significant between both groups | — | Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [37] | UFH | SC | Enoxaparin | 201 | — | No significant difference between CD4 ligand and PAI-1 in both groups | Open label, randomized, clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Skin or pulmonary allergy [38] | UFH | IV/nebulizer | Normal saline/placebo | 25 | Significant inhibition of mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation (P: 0.04) | — | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| COPD [39] | UFH | IV | — | 37 (18 in control group) | Significant improvement in bronchospasm and bronchial secretions (58% response rate) | — | Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| COPD [40] | Nadroparin | SC | Conventional treatment | 66 (33 in each group) | Decrease of duration of mechanical ventilation and length of hospital and ICU stay (P < 0.01) | Significant decrease in levels of CRP, IL-6, and fibrinogen | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Ischemic stroke [41] | UFH | IV | Aspirin | 167 (97 in control group) | Early onset initiation of heparin might improve recovery after stroke | Rise of sVCAM-1 at 48 h was significantly lower in patients treated with UFH (P < 0.01) | Quasi-experimental (controlled observational study) |

|

| |||||||

| Ligneous conjunctivitis [42] | UFH | Topical | Alpha chymotrypsin or steroid | 17 (12 in control group) | Intensive and early use of topical heparin may improve therapy results in disease | — | Quasi-experimental (nonrandomized Clinical trial) |

|

| |||||||

| Endotoxemia (induced by lipopolysaccharide in healthy subjects) [43] | UFH | IV | LMWH or placebo | 30 (10 in each group) | — | No effect on TNF-α, IL-6 and 8, CRP, and E-selectin | Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled parallel group trial |

|

| |||||||

| Mechanical ventilation [44] | UFH | Nebulizer | Normal saline (placebo) | 50 (25 in each group) | Fewer days on mechanical ventilation, better Pao2/Fio2 ratio | — | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Percutaneous coronary intervention [45] | Bivalirudin | IV | UFH + eptifibatide | 63 (29 in control group) | — | Increase in IL-6 and CRP after 1 day. Decrease in CRP in bivalirudin group after 30 days (P: 0.002) | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Cystic fibrosis (adults) [46] | UFH | Inhaler | — | 12 (6 in control group) | Spirometry parameters did not change | IL-6 reduced after treatment | Quasi-experimental (pretest-posttest design) |

|

| |||||||

| Cystic fibrosis (adults) [47] | UFH | Inhaler | Placebo | 14 | No effect on FEV1 | No effect on sputum inflammatory markers | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial |

|

| |||||||

| Hemodialysis patients [48] | UFH | IV/SC | LMWH and no drug | 33 | LMWH decreased oxidative stress and inflammation whereas heparin increased them | CRP, TNF-α, superoxide dismutase, MDA increased in heparin group but comparable to LMWH group | Quasi-experimental (pretest-posttest design) |

|

| |||||||

| Stable angina [49] | Heparin + Aspirin (n = 15) | — | Argatroban + Aspirin (n = 12) 27 | No difference in inflammatory response after angioplasty | Fibrinogen decreased significantly in argatroban group. No difference in von Willberand factor between both groups. PAI-1 increased in argatroban group | Randomized controlled trial | |

|

| |||||||

| Phacoemulsification [50] | Heparin | Coated lenses | Polymethylmethacrylate lenses | 367 | Heparin coated lenses reduced significantly inflammation early postoperation (P: 0.05) | — | Randomized, double-blind, multicenter, parallel group trial |

|

| |||||||

| Allergic rhinitis [51] | UFH | Intranasal | — | 10 | — | Reduction of eosinophil cationic protein in the nasal wash | Quasi-experimental (pretest-posttest design) |

|

| |||||||

| Phacomorphic glaucoma [52] | Dalteparin | Irrigation | Balanced salt solution | 46 (23 in each group) | Significant decrease of postoperative inflammation in dalteparin group | — | Randomized, double-blind, clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Burn [53] | Dalteparin | SC | No treatment | 24 | — | Decrease of nitric oxide synthetase activity significantly | Quasi-experimental (nonrandomized clinical trial) |

|

| |||||||

| Unstable coronary artery disease [54] | Enoxaparin (n = 46) Dalteparin (n = 48) |

SC | UFH (n = 47) | 68 | Von Willberand factor may have prognostic value, but other biological variables did not predict outcome | CRP, fibrinogen, Von Willberand factor increased over first 2 days despite medical treatment. Enoxaparin (13%) and dalteparin (19%) reduced release of Von Willberand factor | Open label, randomized, clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) [55] | Enoxaparin | SC | UFH | 34 (17 in each group) | Both heparin and enoxaparin show anti-inflammatory effects in STEMI patients | Serum Amyloid A (P: 0.02), CRP (P: 0.02), and ferritin (P: 0.01) reduced in heparin group. IL-6 (P: 0.002), SAA (P: 0.009), CRP (P: 0.01) were significantly decreased in enoxaparin group. The overall difference between groups was not significant | Open label, randomized, clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Coronary artery disease [56] | Dalteparin | SC | Placebo | 555 (285 in control group) | Dalteparin reduced coagulation and so Myocardial Infarction but has not inflammatory activity | No effects on IL-6, C-reactive protein and fibrinogen | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre trial |

|

| |||||||

| Stable coronary artery disease [57] | Enoxaparin | SC | Sodium chloride | 62 (31 in each group) | By mobilizing vessel bound MPO, enoxaparin improves endothelial function | Significant increase of MPO levels | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Acute coronary syndrome and PCI [58] | Tirofiban (high dose) + enoxaparin | Tirofiban (high dose) + UFH | 60 (30 in each group) | The combination of tirofiban (high dose) + enoxaparin reduced inflammation after PCI | Von willberand, CRP, D-dimer, and prothrombin fragment were significantly lower in enoxaparin group than UFH | Open label randomized controlled trial | |

|

| |||||||

| Superficial venous thrombophlebitis [59] | Dalteparin | SC | Ibuprofen | 72 (37 in dalteparin group) | Significant reduction of pain form baseline to day 14 of follow-up. No difference on thrombosis progression after 3 months | — | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Superficial venous thrombosis [60] | Nadroparin | SC | Naproxen | 117 (39 in control group) | Nadroparin reduced symptom and signs of thrombosed superficial vein better than naproxen (P: 0.007) | — | Randomized, open label clinical trial |

|

| |||||||

| Superficial venous thrombosis [61] | Nadroparin | SC | Nadroparin + acemetacin | 50 | Significant symptom improvement in both groups (P: 0.001). The combination group was better | — | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| |||||||

| Peritoneal dialysis patients [62] | Tinzaparin | Intraperitoneal | Isotonic saline | 21 | Reduction of local and systemic inflammation in peritoneal dialysis patients | Reduced levels of CRP (P: 0.032) and fibrinogen (P: 0.042) and IL-6 (P: 0.007) in dialysate. | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial |

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, CRP: C-Reactive Protein, CPB: Cardio Pulmonary Bypass, ECP: Eosinophil Cationic Protein, ERCP: Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography, ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation, ICU: Intensive Care Unit, IL: interleukin, IV: intravenous, LMWH: low molecular weight heparin, MDA: malondialdehyde, PAI: Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor, SC: subcutaneous, sVCAM: Soluble Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule, TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor, and UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Table 3 provides information on the adequately reported items according to Jadad score and CONSORT items. Among these 32 papers, 11 (35.4%) scored 2 and the remaining studies scored 3 or higher according to Jadad score and just three studies fulfill the criteria of Jadad score. Calculated quality scores according to CONSORT checklist range from 21% to 70% in our object studies with twelve studies scoring greater than 40%. The following characteristics were not exactly reported in more than half of the trials: identification as a randomized trial in the title, information about the setting and location of studies, determination of sample size, allocation and implementation of randomization, participant flow, recruitment and follow-up, subgroup analysis, limitations of study, harms, registration number, access to full trial protocol, and funding source.

Table 3.

Summary of numbers and percentages of adequately reported items in each trial according to CONSORT checklist and Jadad score.

| Trials | Jadad score | Adequately reported items (n/N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdollahi et al. [52] | 4 | 29/74 | 39.2% |

| Ahmed et al. [9] | 3 | 20/74 | 27% |

| Ang et al. [17] | 2 | 24/74 | 32.4% |

| Ashraf et al. [27] | 2 | 22/74 | 29.7% |

| Becker et al. [37] | 3 | 28/74 | 37.8% |

| de Vroege et al. [29] | 3 | 26/74 | 35.1% |

| Defraigne et al. [28] | 4 | 28/74 | 37.8% |

| Derhaschnig et al. [43] | 3 | 32/74 | 43.2% |

| Dixon et al. [44] | 4 | 50/74 | 67.5% |

| Duong et al. [11] | 3 | 30/74 | 40.5% |

| Gu et al. [71] | 2 | 16/74 | 21.6% |

| Jerzynska et al. [13] | 3 | 20/74 | 27% |

| Keating et al. [45] | 2 | 21/74 | 28.4% |

| Koster et al. [31] | 2 | 26/74 | 35.1% |

| Montalescot et al. [54] | 3 | 35/74 | 47.3% |

| Nasiripour et al. [55] | 2 | 34/74 | 46% |

| Oldgren et al. [56] | 3 | 27/74 | 36.5% |

| Olsson et al. [32] | 2 | 25/74 | 33.8% |

| van Ophoven et al. [79] | 2 | 27/74 | 36.5% |

| Ozawa et al. [33] | 2 | 27/74 | 36.5% |

| Özkurt et al. [24] | 3 | 18/74 | 24.3% |

| Paparella et al. [72] | 2 | 22/74 | 29.7% |

| Polosa et al. [67] | 3 | 23/74 | 31.1% |

| Rathbun et al. [59] | 5 | 44/74 | 59.5% |

| Rudolph et al. [57] | 3 | 31/74 | 41.2% |

| Serisier et al. [47] | 5 | 45/74 | 60.8% |

| Stelmach et al. [16] | 3 | 31/74 | 41.2% |

| Suzuki et al. [49] | 2 | 23/74 | 31% |

| Vancheri et al. [51] | 4 | 22/74 | 29.7% |

| Vasavada et al. [25] | 5 | 52/74 | 70.2% |

| Walters et al. [58] | 3 | 32/74 | 43.2% |

| Zezos et al. [20] | 3 | 37/74 | 50% |

4. Discussion

We discuss evidence from clinical studies supporting an anti-inflammatory role for heparin and heparin-related derivatives.

4.1. Asthma

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of airways characterized by bronchial hyperresponsiveness resulting in episodic bronchospasm. Several studies in 1960s described subjective improvement of symptoms in asthmatic patients using intravenous heparin for the first time [39, 63]. Inhaled heparin or its derivatives have been shown to possess antiasthmatic properties in various clinical models: allergen induced [38, 64], exercise [9], adenosine [6], and distilled water challenge models [65]. Seven randomized controlled crossover trials studied anti-inflammatory effects of heparin in exercise-induced or allergen-induced asthma having sample size range from 8 to 25 in 5 trials.

Heparin inhalation reduced bronchial hyperreactivity in a single-blind randomized crossover trial (n = 12) by Ahmed et al. [9]. Heparin inhalation (1000 μ/kg) prevents exercise-induced asthma (P < 0.05) without prevention of histamine-induced bronchoconstriction. Stelmach et al. [66] provoke challenge tests with histamine or leukotriene D4 before and after inhalation of heparin; showed that heparin (5000 Iu) decreases histamine and leukotriene-induced bronchial hyperreactivity compared to placebo significantly (P: 0.043 and 0.005) but changes in Forced Expiratory Volume (FEV 1) were not significant (P: 0.064). The inhibitory effects of inhaled heparin in the airways in the absence of bronchodilation might be related to suppressive action on mast cell degranulation. A randomized, double-blind study in 10 subjects with asthma showed that heparin inhalation attenuates airway response to adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP) but not to methacholine (P < 0.01) suggesting the theory that heparin acts more likely in association to modulation of mediator release compared to a direct effect on smooth muscle [67].

Our results showed that inhaled enoxaparin was used just in a pre-post study of 24 asthmatic patients, measuring inflammatory biomarkers, and showed a reduction in eosinophil (P: 0.006) and lymphocytes of bronchoalveolar lavage without any significant change in IL-5 or Eosinophil Cationic Protein (ECP) concentrations [12]. Therefore, it seems that enoxaparin could be a valuable add on treatment in asthma like UFH. Duong et al. [11] evaluated IVX-0142 nebulizer, a heparin-derived hypersulfated disaccharide, in asthma and showed nonsignificant decrease in early and late asthmatic response.

Performed studies did not show any adverse events or harms with heparin or related compounds except increase in the plasma partial thromboplastin time reported by Ahmed et al. [9].

All in one, considering the results of these studies, we can conclude that heparin and its derivatives could have anti-inflammatory effects and could be considered along with other treatments in asthma.

4.2. Cardiopulmonary Bypass

Contact and interaction of blood with foreign surfaces during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) cause systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) through activation of several humoral cascades including cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) [68]. The inflammatory response can be attenuated by promoting the biocompatibility of the CPB circuit. Use of heparin-treated surfaces in CPB circuits has been shown to decrease activation of leukocytes and the complement cascades [5]. As a result, need to inotropic support, postoperative time of mechanical ventilation, and rate of acute lung injury decrease and patients duration of hospital stay shortens, which reflects the positive effect of heparin in CPB circuits [69, 70]. Twelve studies whose endpoints were the effects of heparin-bonded circuits on inflammatory markers were included in our analysis and in the majority of these trials [27, 29, 32–35, 71]; heparin-coated circuit significantly decreased the level of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, complement complex, neutrophils, and elastase compared to non-heparin-coated circuit.

Defraigne et al. [28] randomized 200 patients in 4 groups; heparin-coated circuit with or without aprotinin administration and uncoated circuit with or without aprotinin administration. They measured IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and elastase level and concluded that cytokine release and neutrophil activation were not attenuated by heparin-coated circuit or by the administration of aprotinin. Misawa et al. [30] evaluated cytokines level under normothermic CPB, in a small observational controlled study (n = 19, 9 in control group). Levels of IL-6, IL-8, and ICAM-1 (indicator of endothelial damage) were not different between study and control group. However, as mentioned before, most studies indicate the favorable effect of heparin-coated circuit on inflammatory responses in CPB.

Paparella et al. [72] compared two doses of heparin and 300 Iu/kg and 600 Iu/kg in 40 patients undergoing CPB in an RCT and showed that IL-6 and TNF-α plasma levels were in association to heparin dose. It seems that lower heparin dose had small influence on proinflammatory cytokines release; however, higher doses make a better regulatory effect on coagulation system.

The side effects of heparin-coated circuits were not reported. In these studies, just a number of included studies reported a decrease in platelet levels in both groups (coated and noncoated circuit). No major events including hemorrhage were reported.

4.3. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD)

Hypercoagulable state may be an important contributing factor in the pathogenesis of IBD, especially ulcerative colitis (UC) [73]. A number of studies evaluate the effects of heparin administration on UC but the results obtained are controversial [17, 19]. Bloom et al. [74] did not find any favorable effect of LMWH, tinzaparin, over placebo in the treatment of active UC in a double-blind randomized, placebo controlled, multicenter trial (n = 100) evaluating mean change in colitis activity as the primary endpoint. Ang et al. [17] compared heparin to hydrocortisone plus prednisolone in 20 patients (UC, n = 17, Crohn's colitis, n = 3) in open-label randomized crossover trial which measured endpoints; clinical disease activity, stool frequency and α 1 acid glycoprotein, and endoscopic and histopathological grading indicate the efficacy and safety of heparin compared to corticosteroids (P > 0.05); in contrast the study by Panes et al. [19] did not show the efficacy of heparin in UC compared to methylprednisolone.

Zezos et al. [20] compared enoxaparin with standard treatment (aminosalicylate + corticosteroids) in 34 patients with active UC. The inflammatory biomarkers including C-Reactive Protein (CRP), Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR), and fibrinogen did not show any difference in study group compared to control and both groups showed similar rate of disease improvement (P > 0.05); furthermore, coagulation factors did not change from one to another. Authors concluded that enoxaparin is a safe adjuvant but has no additive benefit over standard treatment of UC.

Generally the studies show conflicting results. The heparin and LMWHs showed efficacy in regard of disease activity and also well tolerated but inflammatory markers did not change significantly. Therefore the improvement in disease activity might be the result of heparin's anticoagulant effects.

4.4. Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)

Inflammation has a key role in the pathogenesis of coronary artery plaque destabilization and rupture leading to acute coronary syndromes (ACS) [75]. Leukocyte activation, monocyte, and neutrophil infiltration result in local and systemic inflammatory responses [76]. Heparin and LMWHs are commonly used in ACS to prevent clot formation; they also seem to have desirable effects on inflammatory markers level based on sparse data.

We found 8 studies about heparin and LMWHs in CADs evaluating anti-inflammatory effects as their endpoints. Oldgren et al. [56] found that dalteparin administration in patients with unstable CAD (n = 555) did not affect IL-6, C-Reactive Protein (CRP), and fibrinogen levels, although it reduced coagulation activity and mortality rate in long term, so it is concluded that these effects are not related to its anti-inflammatory properties. Walters et al. [58] compared high dose of tirofiban/enoxaparin (n = 30) with tirofiban/heparin (n = 30) in an open-label randomized controlled trial in high risk percutaneous intervention. They found that combination of high dose of tirofiban with enoxaparin significantly attenuate inflammatory process (decreased levels of CRP, and von Willebrand factor) compared to tirofiban and heparin.

The ARMADA study [54] evaluated anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and enoxaparin in Non-ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction (Non-STEMI) and reported that inflammatory markers (CRP and von Willebrand factor) are affected more by LMWH compared to UFH. However because of the small sample size of the study (n = 68) it did not acquire sufficient statistical power to prove any effects on defined outcomes. Nasiripour et al. [55] found that both enoxaparin and heparin reduce inflammatory markers in STEMI patients at the same level; however, this study had the same limitations of sample size (n = 34) and power too.

In summary considering heparins as the main stay treatment of ACS, its effects are more pronounced as anticoagulating than as an anti-inflammatory agent in this pathological condition.

4.5. Cataract Surgery

Postoperative inflammation is observed in cataract surgery especially in children. Newer techniques as lensectomy and phacoemulsification cause less complication but still pose potential risks [77, 78]. It has been suggested that a heparin surface-modified intraocular lens (IOL) or augmenting the irrigating solution with heparin during cataract surgery may reduce the incidence of postoperative inflammation. Borgioli et al. [22] confirm this hypothesis that heparin surface-modified IOL will reduce the inflammatory response compared to conventional IOL at least in short term period (3 months) in a large (524 patients) double-blind, multicenter trial. A similar study by Colin et al. [23] (n = 58) confirms their results; however, the power of Borgioli et al. study was higher. Heparinized lenses showed also more anti-inflammatory effects during long term follow-up (1 year). Heparinized irrigating solution was used during cataract surgery in two different studies and inflammation decrease observed in the early postoperative period of both studies (Kohnen et al. [26] and Özkurt et al. [24]). Therefore, it seems that heparin in both forms have anti-inflammatory effects in cataract surgery.

Vasavada et al. [25] used enoxaparin irrigation solution in 20 children undergoing bilateral cataract surgery but they did not find any beneficial effect in early postoperative inflammation. This study acquired the highest quality in the study quality assessment process, based on Jadad score and CONSORT items (52/74, 70.2%). It is worth noticing that the majority of items mentioned in the CONSORT checklist were adequately reported and covered in this paper.

Potential mechanisms of anti-inflammatory effects of heparin have been discussed completely in a review by Young [6]. Binding of heparin to different mediators involved in the immune system response (cytokines and chemokines), acute phase proteins, and complement complex proteins may contribute to the anti-inflammatory activity of heparin. Neutralizing of cytokines at the inflammation site is another possible mechanism. In most of the studies level of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and CRP was decreased after heparin administration, which can confirm this mechanism; also heparin and LMWHs inhibit adhesion of leukocytes and neutrophils to endothelial cells by binding to p-selectin, and consequently prevent release of oxygen radicals and proteolytic enzymes. Other possible mechanisms are as follows: inhibition of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and induction of apoptosis by modulation of activity of TNF-α and NF-κB. In a double-blind placebo-controlled trial (n = 62) in patients with stable coronary artery disease, following administration of 1 mg/kg subcutaneous enoxaparin, plasma levels of myeloperoxidase (MPO) increased significantly (P < 0.001) and subsequently endothelial function improved (r = 0.67, P < 0.001) through MPO binding to endothelium and depleting vascular nitric oxide [57]. This study confirms another possible mechanism of heparins anti-inflammatory effects.

5. Conclusion

As we discussed heparins potential effects as anti-inflammatory agents, supported by several clinical trials in various setting. Heparin and its related derivatives have been shown to benefit patients with asthma and patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass and cataract surgery. In other inflammatory diseases, such as IBD (ulcerative colitis), the studies are heterogeneous and incongruent. Most studies did not report any unwanted event with heparins when they used them as anti-inflammatory agents whether through systemic or through local (as inhaler or irrigation or heparin-coated circuit) administration. However, because the majority of these trials did not pose optimal quality scores, we cannot draw a definite conclusion on the efficacy of heparin and its derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents.

The present review included studies which measured inflammatory markers as their endpoints and in most of them these markers were decreased though not significantly. To come to a definite conclusion further double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials with a larger sample size are needed. However, because the inflammation, atherogenesis, thrombogenesis, and cell proliferation are associated with each other, the pleiotropic effects of heparin and related compounds may have greater therapeutic effect than compounds that are directed against a single target.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Casu B. Heparin structure. Pathophysiology of Haemostasis and Thrombosis. 1990;20(supplement 1):62–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsh J., Raschke R., Warkentin T. E., Dalen J. E., Deykin D., Poller L. Heparin: mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing considerations, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. 1995;108(4, supplement):258S–275S. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.4_supplement.258s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fareed J., Hoppensteadt D. A., Bick R. L. An update on heparins at the beginning of the new millennium. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 2000;26(3):5–21. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsh J. Drug therapy: heparin. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324(22):1565–1574. doi: 10.1056/nejm199105303242206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig R. J. Therapeutic use of heparin beyond anticoagulation. Current Drug Discovery Technologies. 2009;6(4):281–289. doi: 10.2174/157016309789869001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young E. The anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and related compounds. Thrombosis Research. 2008;122(6):743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jadad A. R., Moore R. A., Carroll D., et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz K. F., Altman D. G., Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. International Journal of Surgery. 2011;9(8):672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed T., Garrigo J., Danta I. Preventing bronchoconstriction in exercise-induced asthma with inhaled heparin. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(2):90–95. doi: 10.1056/nejm199307083290204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamant Z., Timmers M. C., Van Der Veen H., Page C. P., Van Der Meer F. J., Sterk P. J. Effect of inhaled heparin on allergen-induced early and late asthmatic responses in patients with atopic asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1996;153(6):1790–1795. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duong M., Cockcroft D., Boulet L.-P., et al. The effect of IVX-0142, a heparin-derived hypersulfated disaccharide, on the allergic airway responses in asthma. Allergy. 2008;63(9):1195–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fal A. M., Kraus-Filarska M., Miecielica J., Malolepszy J. Mechanisms of action of nebulized low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with bronchial asthma. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004;113(2, supplement):p. S36. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jerzynska J., Stelmach I., Majak P., Kuna P. The effect of inhaled heparin on airway responsiveness to histamine and metacholine in asthmatic children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002;109(1, supplement 1):p. S39. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalpaklioğlu A. F., Demirel Y. S., Saryal S., Misirligil Z. Effect of pretreatment with heparin on pulmonary and cutaneous response. Journal of Asthma. 1997;34(4):337–343. doi: 10.3109/02770909709067224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stelmach I., Jerzynska J., Brzozowska A., Kuna P. The effect of inhaled heparin on postleukotriene bronchoconstriction in children with asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002;109(1, supplement 1):p. S39. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stelmach I., Jerzynska J., Stelmach W., et al. The effect of inhaled heparin on airway responsiveness to histamine and leukotriene D4. Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 2003;24(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang Y. S., Mahmud N., White B., et al. Randomized comparison of unfractionated heparin with corticosteroids in severe active inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2000;14(8):1015–1022. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folwaczny C., Wiebecke B., Loeschke K. Unfractioned heparin in the therapy of patients with highly active inflammatory bowel disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94(6):1551–1555. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panes J., Esteve M., Cabre E., et al. Comparison of heparin and steroids in the treatment of moderate and severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(4):903–908. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zezos P., Papaioannou G., Nikolaidis N., et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin) as adjuvant therapy in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomized, controlled, comparative study. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;23(10):1443–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vrij A. A., Jansen J. M., Schoon E. J., Hemker H. C., Stockbrügger R. W. Low molecular weight heparin treatment in steroid refractory ulcerative colitis: clinical outcome and influence on mucosal capillary thrombi. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, Supplement. 2001;36(234):41–47. doi: 10.1080/003655201753265091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borgioli D. M., Coster D. J., Fan R. F. T., et al. Effect of heparin surface modification of polymethylmethacrylate intraocular lenses on signs of postoperative inflammation after extracapsular cataract extraction: one-year results of a double-masked multicenter study. Ophthalmology. 1992;99(8):1248–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31816-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colin J., Roncin S., Wenzel M. Efficacy of heparin surface-modified IOLs in reducing postoperative inflammatory reactions in patients with exfoliation syndrome—a double-blind comparative study. European Journal of Implant and Refractive Surgery. 1995;7(5):266–270. doi: 10.1016/s0955-3681(13)80416-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Özkurt Y. B., Taşkiran A., Erdogan N., Kandemir B., Doğan Ö. K. Effect of heparin in the intraocular irrigating solution on postoperative inflammation in the pediatric cataract surgery. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2009;3(1):363–365. doi: 10.2147/opth.s5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasavada V. A., Praveen M. R., Shah S. K., Trivedi R. H., Vasavada A. R. Anti-inflammatory effect of low-molecular-weight heparin in pediatric cataract surgery: a randomized clinical trial. The American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2012;154(2):252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohnen T., Dick B., Hessemer V., Koch D. D., Jacobi K. W. Effect of heparin in irrigating solution on inflammation following small incision cataract surgery. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery. 1998;24(2):237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(98)80205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashraf S., Tian Y., Cowan D., Entress A., Martin P. G., Watterson K. G. Release of proinflammatory cytokines during pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass: heparin-bonded versus nonbonded oxygenators. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1997;64(6):1790–1794. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Defraigne J.-O., Pincemail J., Larbuisson R., Blaffart F., Limet R. Cytokine release and neutrophil activation are not prevented by heparin- coated circuits and aprotinin administration. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2000;69(4):1084–1091. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)01093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Vroege R., van Oeveren W., van Klarenbosch J., et al. The impact of heparin-coated cardiopulmonary bypass circuits on pulmonary function and the release of inflammatory mediators. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2004;98(6):1586–1594. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000114551.64123.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misawa Y., Kawahito K., Konishi H., Fuse K. Cytokine mediated endothelial activation during and after normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass: Heparin-bonded versus non heparin-bonded circuits. ASAIO Journal. 2000;46(6):740–743. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200011000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koster A., Fischer T., Praus M., et al. Hemostatic activation and inflammatory response during cardiopulmonary bypass: impact of heparin management. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(4):837–841. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsson C., Siegbahn A., Henze A., et al. Heparin-coated cardiopulmonary bypass circuits reduce circulating complement factors and interleukin-6 in paediatric heart surgery. Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal. 2000;34(1):33–40. doi: 10.1080/14017430050142378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozawa T., Yoshihara K., Koyama N., Watanabe Y., Shiono N., Takanashi Y. Clinical efficacy of heparin-bonded bypass circuits related to cytokine responses in children. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2000;69(2):584–590. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parolari A., Alamanni F., Gherli T., et al. ‘High dose’ aprotinin and heparin-coated circuits: Clinical efficacy and inflammatory response. Cardiovascular Surgery. 1999;7(1):117–127. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(98)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada H., Kudoh I., Hirose Y., Toyoshima M., Abe H., Kurahashi K. Heparin-coated circuits reduce the formation of TNFα during cardiopulmonary bypass. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1996;40(3):311–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1996.tb04438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barkay O., Niv E., Santo E., Bruck R., Hallak A., Konikoff F. M. Low-dose heparin for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2008;22(9):1971–1976. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9738-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becker R. C., Mahaffey K. W., Yang H., et al. Heparin-associated anti-Xa activity and platelet-derived prothrombotic and proinflammatory biomarkers in moderate to high-risk patients with acute coronary syndrome. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. 2011;31(2):146–153. doi: 10.1007/s11239-010-0532-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowler S. D., Smith S. M., Lavercombe P. S. Heparin inhibits the immediate response to antigen in the skin and lungs of allergic subjects. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1993;147(1):160–163. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyle J. P., Smart R. H., Shirey J. K. Heparin in the treatment of chronic obstructive bronchopulmonary disease. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1964;14(1):25–28. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(64)90100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qian Y., Xie H., Tian R., Yu K., Wang R. Efficacy of low molecular weight heparin in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease receiving ventilatory support. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2014;11(2):171–176. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.831062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chamorro Á., Cervera Á., Castillo J., Dávalos A., Aponte J. J., Planas A. M. Unfractionated heparin is associated with a lower rise of serum vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in acute ischemic stroke patients. Neuroscience Letters. 2002;328(3):229–232. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Cock R., Ficker L. A., Dart J. G., Garner A., Wright P. Topical heparin in the treatment of ligneous conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(11):1654–1659. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30813-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derhaschnig U., Pernerstorfer T., Knechtelsdorfer M., Hollenstein U., Panzer S., Jilma B. Evaluation of antiinflammatory and antiadhesive effects of heparins in human endotoxemia. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31(4):1108–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059441.70680.DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dixon B., Schultz M. J., Smith R., Fink J. B., Santamaria J. D., Campbell D. J. Nebulized heparin is associated with fewer days of mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Critical Care. 2010;14(5, article R180) doi: 10.1186/cc9286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keating F. K., Dauerman H. L., Whitaker D. A., Sobel B. E., Schneider D. J. The effects of bivalirudin compared with those of unfractionated heparin plus eptifibatide on inflammation and thrombin generation and activity during coronary intervention. Coronary Artery Disease. 2005;16(6):401–405. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200509000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ledson M., Gallagher M., Hart C. A., Walshaw M. Nebulized heparin in Burkholderia cepacia colonized adult cystic fibrosis patients. European Respiratory Journal. 2001;17(1):36–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17100360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serisier D. J., Shute J. K., Hockey P. M., Higgins B., Conway J., Carroll M. P. Inhaled heparin in cystic fibrosis. European Respiratory Journal. 2006;27(2):354–358. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00069005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poyrazoglu O. K., Dogukan A., Yalniz M., Seckin D., Gunal A. L. Acute effect of standard heparin versus low molecular weight heparin on oxidative stress and inflammation in hemodialysis patients. Renal Failure. 2006;28(8):723–727. doi: 10.1080/08860220600925594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki S., Matsuo T., Kobayashi H., et al. Antithrombotic treatment (argatroban vs. heparin) in coronary angioplasty in angina pectoris: effects on inflammatory, hemostatic, and endothelium-derived parameters. Thrombosis Research. 2000;98(4):269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(99)00237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trocme S. D., Li H.-I. Effect of heparin-surface-modified intraocular lenses on postoperative inflammation after phacoemulsification: a randomized trial in a United States patient population. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(6):1031–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vancheri C., Mastruzzo C., Armato F., et al. Intranasal heparin reduces eosinophil recruitment after nasal allergen challenge in patients with allergic rhinitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2001;108(5):703–708. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abdollahi A., Naini M.-T., Shams H., Zarei R. Effect of low-molecular-weight heparin on postoperative inflammation in phacomorphic glaucoma. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2002;5(4):225–229. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lakshmi R. T. S., Priyanka T., Meenakshi J., Mathangi K. R., Jeyaraman V., Babu M. Low molecular weight heparin mediated regulation of nitric oxide synthase during burn wound healing. Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters. 2011;24(1):24–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Montalescot G., Bal-dit-Sollier C., Chibedi D., et al. Comparison of effects on markers of blood cell activation of enoxaparin, dalteparin, and unfractionated heparin in patients with unstable angina pectoris or non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (the ARMADA study) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2003;91(8):925–930. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nasiripour S., Gholami K., Mousavi S., et al. Comparison of the effects of enoxaparin and heparin on inflammatory biomarkers in patients with ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction: a prospective open label pilot clinical trial. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2014;13(2):583–590. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oldgren J., Fellenius C., Boman K., et al. Influence of prolonged dalteparin treatment on coagulation, fibrinolysis and inflammation in unstable coronary artery disease. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2005;258(5):420–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rudolph T. K., Rudolph V., Witte A., et al. Liberation of vessel adherent myeloperoxidase by enoxaparin improves endothelial function. International Journal of Cardiology. 2010;140(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walters D. L., Ray M. J., Wood P., Perrin E. J., Bett J. H. N., Aroney C. N. High-dose tirofiban with enoxaparin and inflammatory markers in high-risk percutaneous intervention. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;40(2):139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rathbun S. W., Aston C. E., Whitsett T. L. A randomized trial of dalteparin compared with ibuprofen for the treatment of superficial thrombophlebitis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2012;10(5):833–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Titon J. P., Auger D., Grange P., et al. Therapeutic management of superficial venous thrombosis with calcium nadroparin. Dosage testing and comparison with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent. Annales de Cardiologie et d Angéiologie. 1994;43(3):160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uncu H. A comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin and combined therapy of low-molecular-weight heparin with an anti-inflammatory agent in the treatment of superficial vein thrombosis. Phlebology. 2009;24(2):56–60. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2008.008025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sjøland J. A., Pedersen R. S., Jespersen J., Gram J. Intraperitoneal heparin ameliorates the systemic inflammatory response in PD patients. Nephron—Clinical Practice. 2005;100(4):c105–c110. doi: 10.1159/000085289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fine N. L., Shim C., Williams M. H., Jr. Objective evaluation of heparin in the treatment of asthma. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1968;98(5):886–887. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1968.98.5.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diamant Z., Timmers M. C., van der Veen H., Page C. P., van der Meer F. J., Sterk P. J. Effect of inhaled heparin on allergen-induced early and late asthmatic responses in patients with atopic asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1996;153(6 I):1790–1795. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tranfa C. M. E., Vatrella A., Parrella R., Pelaia G., Bariffi F., Marsico S. A. Effect of inhaled heparin on water-induced bronchoconstriction in allergic asthmatics. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2001;57(1):5–9. doi: 10.1007/s002280100262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stelmach I., Jerzyńska J., Brzozowska A., Kuna P. The effect of inhaled heparin on postleukotriene bronchoconstriction in children with asthma. Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski. 2002;12(68):95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Polosa R., Magrì S., Vancheri C., et al. Time course of changes in adenosine 5′-monophosphate airway responsiveness with inhaled heparin in allergic asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1997;99(3):338–342. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Butler J., Rocker G. M., Westaby S. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1993;55(2):552–559. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)91048-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Redmond J. M., Gillinov A. M., Stuart R. S., et al. Heparin-coated bypass circuits reduce pulmonary injury. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1993;56(3):474–479. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90882-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Svenmarker S., Sandström E., Karlsson T., et al. Clinical effects of the heparin coated surface in cardiopulmonary bypass. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 1997;11(5):957–964. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(97)88351-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gu Y. J., van Oeveren W., Akkerman C., Boonstra P. W., Huyzen R. J., Wildevuur C. R. H. Heparin-coated circuits reduce the inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1993;55(4):917–922. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90117-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paparella D., Al Radi O. O., Meng Q. H., Venner T., Teoh K., Young E. The effects of high-dose heparin on inflammatory and coagulation parameters following cardiopulmonary bypass. Blood Coagulation and Fibrinolysis. 2005;16(5):323–328. doi: 10.1097/01.mbc.0000172328.58506.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Danese S., Papa A., Saibeni S., Repici A., Malesci A., Vecchi M. Inflammation and coagulation in inflammatory bowel disease: the clot thickens. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;102(1):174–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bloom S., Kiilerich S., Lassen M. R., et al. Low molecular weight heparin (tinzaparin) vs. placebo in the treatment of mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2004;19(8):871–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Libby P. Coronary artery injury and the biology of atherosclerosis: inflammation, thrombosis, and stabilization. American Journal of Cardiology. 2000;86(8) doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mulvihill N. T., Foley J. B. Inflammation in acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2002;87(3):201–204. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jameson N. A., Good W. V., Hoyt C. S. Inflammation after cataract surgery in children. Ophthalmic Surgery. 1992;23(2):99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sinskey R. M., Amin P. A., Lingua R. Cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation in an infant with a monocular congenital cataract. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery. 1994;20(6):647–651. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Ophoven A., Heinecke A., Hertle L. Safety and efficacy of concurrent application of oral pentosan polysulfate and subcutaneous low-dose heparin for patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2005;66(4):707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]